Psychiatry is a specialty developed in the 19th and 20th centuries. How could there have been a psychiatrist in the court of Philip II, King of Spain between 1556 and 1596? Of course, there could not have been and there was not a psychiatrist in Philip II's court. The title of this article is an invitation for recognition of Renaissance European mental medicine, understood as that practiced between the times of Petrarch (1304–1374) and Descartes (1596–1650) as the historical foundation of psychiatry. “During the 16th and 17th centuries, mental medicine gained its citizenship rights,” wrote psychiatrist Henri Ey with an appropriate analogy in his 1969 book, Treatise on Psychiatry.1 Renaissance mental health care or mental medicine is not a synonym of or a mere precursor of psychiatry. However, without Renaissance mental medicine, it would have been very difficult, perhaps impossible, for psychiatry or clinical psychology to emerge a few centuries later. This assertion includes a good deal of presentism (or historical anachronism). Presentism consists of using present concepts to study and interpret the past, defending a triumphalist version of history (the future will bring victory for truth over past), and using past events to legitimise the present. However, the past can only be investigated from the present, as the historical view is conditioned, even determined, by the time and place of the investigator, so some presentist bias is inevitable, and worth acknowledging.2

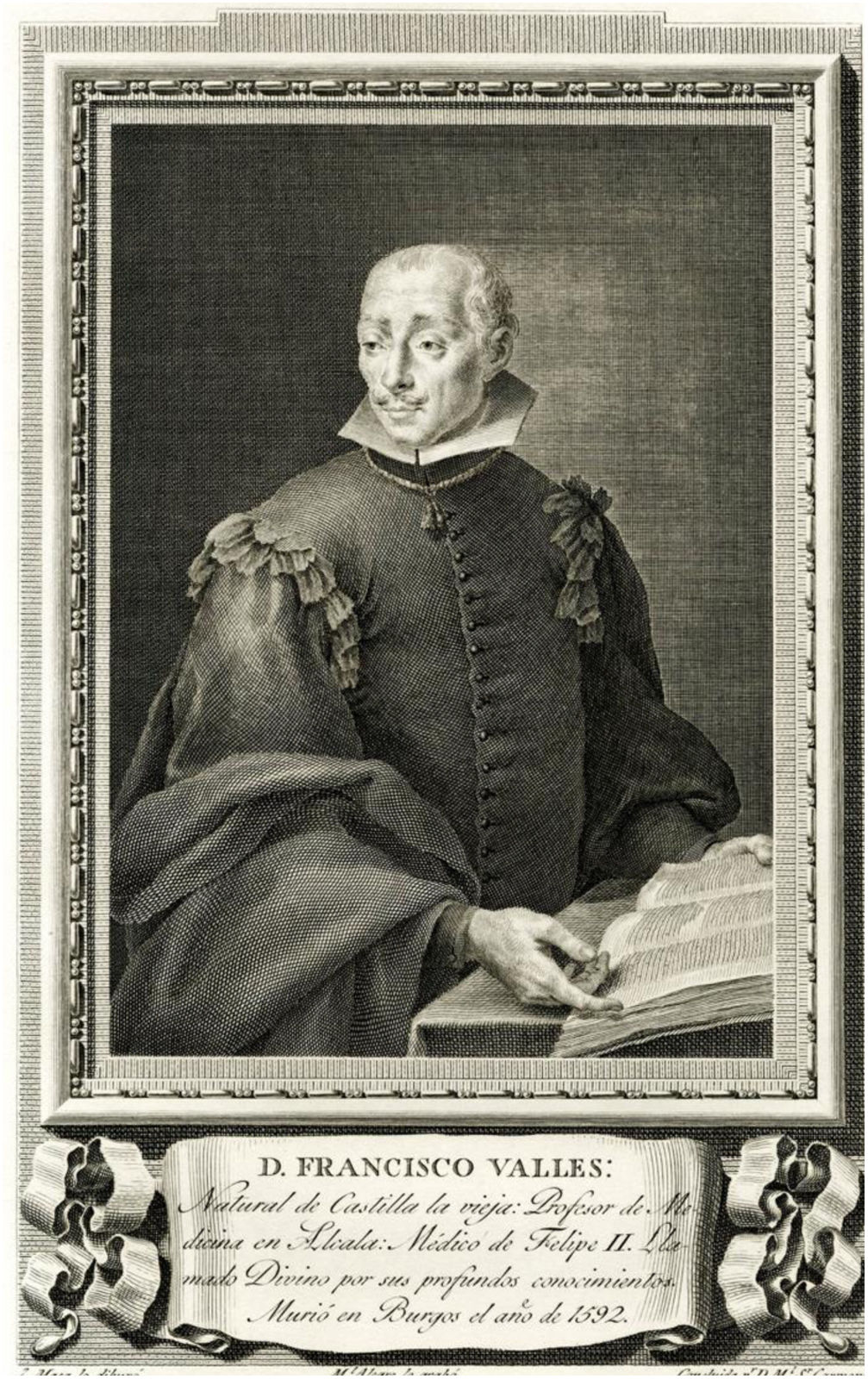

Francisco Valles (1524–1592), also known as Divino Valles, was born in Covarrubias, Spain, and studied at the University of Alcalá de Henares, where he graduated in arts in 1547 and in medicine in 1553. He was a professor there between 1557 and 1572 and physician to Philip II from 1572. His medicine classes at the University of Alcalá included practical anatomy lessons through cadaver dissections, leading some authors to consider him the founder of modern pathological anatomy. Valles achieved great prestige within and outside the court and the Divino Valles Hospital in Burgos is named for him. He was appointed by the king as the “chief physician general of all the Kingdoms and Lordships of Castile” and dealt with tasks such as the official regulation of pharmaceutical weights and measures or the organisation of the library of the El Escorial monastery.3

He published at least fifteen works, including a gloss of biblical texts and several commentaries on Aristotle's work, but most of his production was dedicated to medicine.

Valles’ books had great reach and influence for more than two hundred years among prominent European physicians. Herman Boerhaave (1668–1738), considered by many the main founder of modern clinical medicine, wrote: “He who has the comments of this Spaniard [Valles] needs no others”3 (Fig. 1).

Portrait of Francisco Valles. Etching and burin (soft-ground etching) by Juan Barcelón y Abellán (1739–1801). Inscription: D. FRANCISCO VALLES: Natural de Castilla la vieja: Profesor de Medicina en Alcala: Médico de Felipe II. Llamado Divino por sus profundos conocimientos. Murió en Burgos en el año de 1592. J. Maea lo dibuxó. Ml Alegre lo grabó. Concluida p.r D. M.l S.r Carmona. [D. FRANCISCO VALLES: Native of Old Castile: Professor of Medicine in Alcalá: Physician to Philip II. Called Divine for his profound knowledge. He died in Burgos in the year 1592. J. Maea drew it. Ml Alegre engraved it. Completed by D. M.l S.r Carmona.] Image from the Department of National Engraving, Inventory Number: R-2804, Plate Registration Number: M-2804, Collection: Illustrious Spaniards, Series: 18th Century, Engraver's Name: Manuel Salvador Carmona, Artist's Name: José Maea (1760–1826). From: https://www.academiacolecciones.com/estampas/inventario.php?id=R-2804.

Francisco Valles’ work notably contributed to the advancement of Renaissance medicine.

Francisco Valles embraced the humoral doctrine prevalent in Europe from Antiquity until well into the 18th century. The humoral doctrine (of the four humours: black bile or melancholy, yellow bile or choler, phlegm or pituita, and blood) has its roots in archaic traditions, whose ultimate origin is unknown. It was developed by the Hippocratic school (Hippocrates lived in the 5th century BC) and reformulated by Galen (131–200 CE).2

Francisco Valles considered himself a follower of Galenic humoral doctrine,3–5 which gives special importance to the correct balance (krasis) of the four humours as a necessary condition for health and considers the preponderance of any of them (dyscrasia) as a pathological state. The humours have four basic qualities (warm, cold, dry, and wet; melancholy is cold and dry; choler, hot and dry; phlegm, cold and wet; and blood, hot and wet) whose imbalance determines temperament. From the 12th century, through the influence of scholastic philosophy, medical doctors granted a decisive role to temperament, as a stable disposition of the nature of being and the tendency to become ill. “The proportional mix of warm, cold, wet, and dry is called temperament,” Valles wrote. The Galenic conception of illness and temperaments is somatic, meaning it holds that illness processes occur in the body, and does not conceive the existence of diseases of the soul. In that framework, mental medicine is the medical treatment of diseases that alter the faculties of the rational part of the soul (internal senses) or the passions (movements of the soul). The faculties of the rational soul (imaginative or fantasy; understanding, estimative or cogitative; and memory) are, in turn, determined by the type of imbalance of the basic qualities. The imaginative faculty comes from warm and dry humours, the estimative faculty comes from dry humours, and memory comes from warm and wet humours.2

Francisco Valles did not limit himself to reproducing the knowledge dictated by humoral orthodoxy. He made rational critiques of traditional medical knowledge, especially that of Hippocrates and Galen, and showed a decided preference for clinical observation over the theory (based on classical texts) as a source of knowledge. “We do not want to swear by anyone's words but to bring truth in whatever it may be, whoever says it,” Valles declared.4 With this critical and clinical mentality, Valles was able to delve into the territory of mental medicine, as this required a new perspective (less laden with prejudices and less subject to classical teachings) and attentive to clinical reality. Due to his nonconformity, Valles’ work was highly appreciated by authors with an antisystematic sceptical mentality (opposed to uncritically accepting humoral tradition) that decisively influenced the transition towards anatomoclinical medicine in the 18th and 19th centuries.3

For the sake of brevity required by this article, I will summarise Francisco Valles’ contribution to Renaissance mental medicine: (1) his proposal for the classification of mental illnesses; (2) his influence on the emancipation process of the mental realm; and (3) his commitment to elucidating the pathogenic mechanisms of mental illnesses.

Valles did not create a systematic classification of mental illnesses (or to acknowledge our presentist bias, what we today call mental illnesses). In fact, the classifications he presented, like many disease classifications before the 19th century, abound in contradictions. Valles classified mental illnesses into two broad groups: (a) those caused by depravity of the faculties of the soul, and (b) those caused by the decline in the faculties.

He named the first group (alteration or depravation of faculties) dementia, insanity, or delirium, interchangeably; in this group, we find mania and melancholy (afebrile forms) and phrenitis and lethargy (febrile forms). The second group (decrease of faculties) includes fatuity (decrease of the imaginative), amentia (of reason), and oblivion (of memory).5 Valles added a comment that is still relevance on mental illness classification: “the differences in diseases are of two kinds: some are obtained from the nature of things, […]; but others are not according to their essence, but are species that doctors adopt for their practice”.5

Valles’ comment foreshadowed today's debate on the validity and utility of diagnoses.

Despite the radical somaticism of Renaissance medicine, this era witnessed a progressive trend despite setbacks towards emancipation of the mental from the physical. This emancipation was indebted to the cultural Renaissance context in which perspective (that is, the view from the place a person occupies) and mental space acquire prominence in art. For example, The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490–1500) by Hieronymus Bosch shows images that do not exist outside the mind, and Don Quixote, by Miguel de Cervantes, and many of Shakespeare's works, examine inner worlds. Francisco Valles used the difference between the soul, which he described as the scaffolding of the mind, and sometimes as its equivalent, and the body to explain the mechanisms underlying certain forms of illness. “These juices [phlegm and blood], when they lean towards the body, produce paralysis, and when they lean towards the soul, fatuity [decrease of the imaginative faculty], just as atrabilious juices (black bile) when they lean towards the soul produce madness and when they lean towards the body, convulsions,” Valles writes.6 Of course, Valles did not accept that the mind could not be in an intimate relationship or sympathy with the body, “for nothing is more united to the body than what comes from the soul”.6 However, his statements indicate that he considered the mind not something that can be subsumed into the body, but which instead occupies or corresponds to its own space, overlapping with or subjected to the body, but its own.

The mental space in Valles’ work is also evident in the diagnostic importance he grants to the content of dreams as a manifestation of the soul or mind. Valles explains: “Let me recount something that happened to me in Alcalá [de Henares] recently. A patient was very distressed one night. When I went to see him in the morning, I asked him what was troubling him, and he replied: ‘Dreams. I dreamt’, he said, ‘that I had built a house in the middle of the river, and that the river rose a lot, sweeping it all away; I lamented excessively that the river took away all my work and property.’ I started to ask those present if this patient was sad about something, and I heard, as the wife said, that he had started to get sick due to sadness, as he had made many bricks of soil and, after putting them in the oven, it suddenly started raining, rain that lasted all day and ruined them […].

Upon hearing this, I understood that the soul itself was revealing to me, through an allegory, the cause of the illness, calling the bricks a house and the rain a river.”7

A text like this, written in the 16th century, seems like a beautiful prelude (if we can forgive the presentism) to other fundamental works published in the centuries to come.

Francisco Valles did not accept traditional hypotheses for the pathogenic mechanisms of diseases without revision or critique. On the contrary, he rolled up his sleeves and offered new readings of old problems. The dispute between Galen and Averroes (1126–1198) about how black bile causes melancholy was famous in those times. “The generation of fear and sadness [symptoms of melancholy since Hippocrates] Galen does not attribute so much to altering qualities [that is, the basic qualities: warm, cold, dry, and wet] as to colour,” explains Valles. “Averroes laughs at this opinion,”4 Valles continues, and quotes Averroes: “colour cannot do anything if it is not perceived, for it is neither an efficient quality nor does it engender anything […], therefore in no way can the black colour of the humour introduce fear or sadness […]. Thus, those symptoms are not produced by colour but by the temperamental imbalance of the brain.” Valles accepts part of Averroes’ critique of Galen, accepting that the brain, the indisputable seat in the Renaissance of the main form of melancholy, cannot perceive black. However, as expected, Valles comes to Galen's aid, who issued his verdict on the decisive role of the black colour of bile in melancholy without offering reasoning to support his assertion. But Valles does offer reasoning: “The black colour of the humour obscures the brilliance of the spirits [a kind of subtle matter that circulates through arteries and nerves and serves as a link between body and soul, and between the external and internal worlds], and therefore the mind moves in an altered way due to the deficiency of its own instrument […]; melancholic disease does not occur without melancholic humour […]. Thus, the temperamental imbalance produces the black humour, the black colour darkens the spirit, and the darkening of the spirit produces fear and sadness.” Valles adds, elsewhere, that: “it is necessary for melancholics to become sad when the seat of the soul is invaded by black vapours [coming from black bile], and that occasionally, when the copious fumigation ceases and the movement of the black juice [black bile] mitigates, they become free from sadness.”7

Valles’ explanation, as we see, provides conceptual support for Galen's assertion and an explanation of the pathogenic mechanism of melancholy and its cure.

The Renaissance witnessed the advent of printing, great voyages and the cartographic revolution, the heliocentric theory and the arts, mathematics, and modern nations. It also witnessed the birth of mental medicine, a prelude (from our, presentist, point of view) to psychiatry, psychoanalysis, and clinical psychology. Francisco Valles was one of the main contributors to its development. This brief work pays him well-deserved tribute and invites you to explore his work.

Conflicts of interestThe author declares no conflicts of interest in the publication of this article.

This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI20/00216, PI23/00211) and co-funded by the European Union.

![Portrait of Francisco Valles. Etching and burin (soft-ground etching) by Juan Barcelón y Abellán (1739–1801). Inscription: D. FRANCISCO VALLES: Natural de Castilla la vieja: Profesor de Medicina en Alcala: Médico de Felipe II. Llamado Divino por sus profundos conocimientos. Murió en Burgos en el año de 1592. J. Maea lo dibuxó. Ml Alegre lo grabó. Concluida p.r D. M.l S.r Carmona. [D. FRANCISCO VALLES: Native of Old Castile: Professor of Medicine in Alcalá: Physician to Philip II. Called Divine for his profound knowledge. He died in Burgos in the year 1592. J. Maea drew it. Ml Alegre engraved it. Completed by D. M.l S.r Carmona.] Image from the Department of National Engraving, Inventory Number: R-2804, Plate Registration Number: M-2804, Collection: Illustrious Spaniards, Series: 18th Century, Engraver Portrait of Francisco Valles. Etching and burin (soft-ground etching) by Juan Barcelón y Abellán (1739–1801). Inscription: D. FRANCISCO VALLES: Natural de Castilla la vieja: Profesor de Medicina en Alcala: Médico de Felipe II. Llamado Divino por sus profundos conocimientos. Murió en Burgos en el año de 1592. J. Maea lo dibuxó. Ml Alegre lo grabó. Concluida p.r D. M.l S.r Carmona. [D. FRANCISCO VALLES: Native of Old Castile: Professor of Medicine in Alcalá: Physician to Philip II. Called Divine for his profound knowledge. He died in Burgos in the year 1592. J. Maea drew it. Ml Alegre engraved it. Completed by D. M.l S.r Carmona.] Image from the Department of National Engraving, Inventory Number: R-2804, Plate Registration Number: M-2804, Collection: Illustrious Spaniards, Series: 18th Century, Engraver](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/29502853/unassign/S2950285324000425/v1_202409020425/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)