In the excellent Epistemology of Psychiatry, originally published in 2024, Berrios and Luque dedicate a chapter to phenomenological philosophy and the much-debated way in which Jaspers applied it to psychopathology. They cite an overwhelming bibliography on the subject, both classic and recent. What stands out, therefore, is the special importance they give to what they call Luis Martín-Santos’ “classic work”: Dilthey, Jaspers and the Understanding of the Mentally Ill [original Dilthey, Jaspers y la comprensión del enfermo mental] (1955).

However, it is not psychiatry that explains Martín-Santos’ fame, but the masterful novel Tiempo de silencio (1962), with which he propelled the evolution of Spanish literature from the traditional realism that then prevailed towards the type of avant-garde that, in world literature, Joyce had brought to its culmination with Ulysses (1922) forty years earlier. And the comparison is not arbitrary: among the many fruitful readings that lie behind Tiempo de silencio, Joyce's work clearly stands out. No one in Spain had previously managed to assimilate (not mimic) the narrative innovations with which Joyce's gaze radiographed Dublin and apply them as a recreation (not an imitation) to Madrid in the 1940s.

Martín-Santos had an inner force of such calibre that he lived, in the scant forty years of his existence, several lives, followed by several legends about his death. That is why an early attempt to make him known, when the character was still a famous unknown, bore the title Lives and Deaths of Luis Martín-Santos (Lázaro, 2009) [original Vidas y muertes de Luis Martín-Santos]. In his lightning-fast passage through life, he was a fascinating seducer to both men and women, a coldly aloof figure to the bores who approached him, a vocational metaphysician and, at the same time, a rigorous scientist, a clandestine political activist who struggled in vain to change his country and a novelist who changed its literature, a Berlangaesque aspirant to a professorship in Franco's Spain, and a constant provocateur on the verge of histrionics, a loving father remembered by his children, and a joyful reveller known to his nocturnal friends, a shy, solitary, withdrawn child and a proud, dazzling, verbose man…

The publication of his Complete Works [Original Obras Completas], an admirable initiative begun by Galaxia Gutenberg in 2024, will reveal to the general public what until now few have known: the writings that Martín-Santos left unpublished at his death, and which have remained so for sixty years, are more numerous than his published texts. It seems that with this, the sixty years of silence that his heirs imposed on this ocean of texts are coming to an end (Fig. 1).

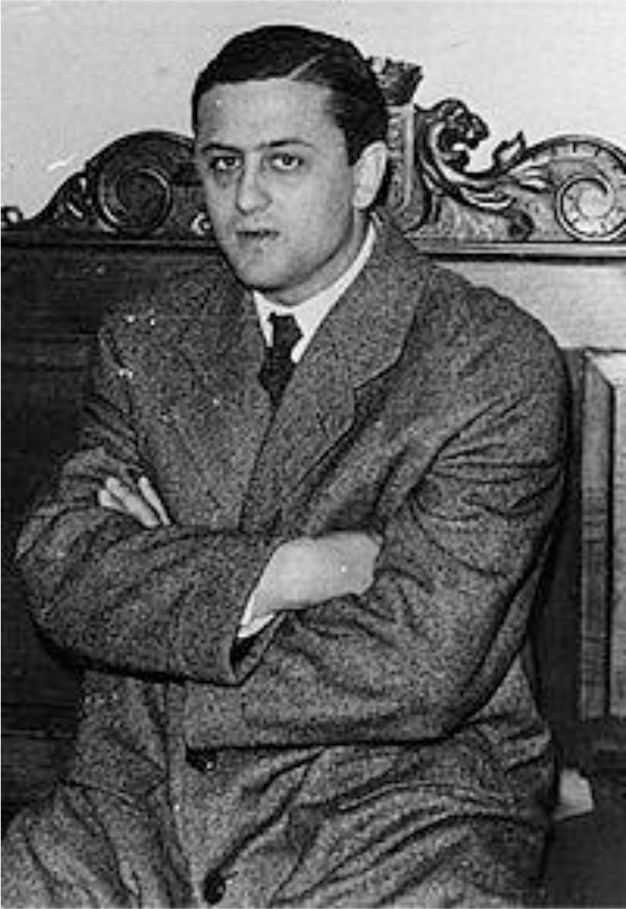

Luis Martín-Santos (1924–1964). Born in Larache (Marocco), at the age of four, his father (a military doctor) was transferred to San Sebastián, where Martín-Santos lived his entire life, except for the years spent in Madrid for his doctorate and specialisation. He was the director of the Psychiatric Hospital in San Sebastián.

The psychiatric part of his work does not have the historical significance of his novels, and is heavily influenced by the time in which it was written, but it is of a quality that again demonstrates the exceptional intellectual gifts of its author. Within it, there is a line of great internal coherence and general interest that gathers the theoretical inheritances on which he based his personal conception of normal and pathological psychology, his analyses of human existence, and his own way of understanding mental disorders and psychotherapy. These writings are what we attempted to compile selectively in the volume Existential Analysis. Essays (2004). The collection brought together the foundations of his theoretical thinking (the genealogy of his intellectual roots), the application of that theory to the study of everyday life, and the personal development of a psychotherapy for neuroses. The thematic range of that selection of texts was clear from their titles (all originally in Spanish): “Jean-Paul Sartre's Existential Psychoanalysis,” “Existential Psychiatry [Heidegger],” “Jaspers and Freud,” “The Naturalist, His Psychology,” “Man's Sexual Surplus, Love and Eroticism,” “Understanding Madness [Interview],” “Theoretical Foundations of Psychiatric Knowledge,” “Training the Psychotherapist,” and Freedom, Temporality, and Transference in Existential Psychoanalysis: Towards a Phenomenology of Psychoanalytic Cure.

But his contribution to psychiatry is not limited to these texts; it also extends to other epistemological reflections (all originally in Spanish “Experimental Psychiatry,” “Dialectics, Totalisation and Awareness”), fine psychopathological analyses (“The Problem of Alcoholic Hallucinosis,” “Primary Delusional Ideas, Schizophrenia and Acute Alcoholic Psychosis,” “Lack of Phenomenological Reality in the Double Membration of the So-called ‘Delusional Perceptions’ Described by Kurt Schneider”), clinical studies (“The Problem of Alcoholic Hallucinosis,” “Phenomenological Description and Existential Analysis of Some Acute Epileptic Psychoses”), and research on psychotechnical tests (“Description and Provisional Statistical Validation of a Spanish Adaptation of the Wechsler-Bellevue Scale for Adult Intelligence,” “Correlations Between the Rorschach Test and Electroencephalographic Findings in a Group of 50 Patients Subjected to Convulsive Treatment”). To all this must be added suggestive essayistic incursions (“Lope de Aguirre: Madman?,” “Baroja-Unamuno”). But all these texts, published in his lifetime or shortly after his death, are only part of what he wrote.

The current promise to publish all of Martín-Santos’ psychiatric work within his Complete Works deserves the most enthusiastic applause and is a brave and risky venture on the part of the Galaxia Gutenberg publishing house. The nature of the texts will not make it easy. Dilthey, Jaspers and the Understanding of the Mentally Ill (whose first and only edition in 1955, of one thousand copies, has been out of print for decades) is an excellent doctoral thesis that devotes two hundred pages to summarising a meticulous reading of the two thinkers who give it its title. The author's original contribution, the final chapter of the thesis, was transformed into an article and published that same year: it is the aforementioned “Theoretical Foundations of Psychiatric Knowledge.” Among the other works published in professional journals, there are some of considerable length and very technical content. The volume of posthumous psychiatric writings that Castilla del Pino sent to Barral—and which he lost—seem to be only part of the unpublished writings preserved in his archive. The two professorship memos written for separate competitions, praised by Castilla del Pino in 1964 when he advocated for their publication, also remain unpublished; years later, he changed his mind, considering that they included ideological opinions contrary to the author's convictions, inauthentically embedded in the text to “gain the favour” of the ultra-conservative members of the tribunal. And to all this must be added the unpublished, more or less fragmentary, manuscripts that his daughter has safeguarded. The task ahead for the editors of this material is not enviable.

Given this complicated scenario, the rigour and skill with which the editor of the Complete Works, Domingo Ródenas de Moya, has prepared the first volume, dedicated to the short stories, never before published in a complete, coherent, and orderly manner, is very promising. However, the value and merits of this first volume drop several points in the second, which publishes for the fourth time Martín-Santos’ most well-known professional work: Freedom, Temporality, and Transference in Existential Psychoanalysis: Towards a Phenomenology of Psychoanalytic Cure (1st ed., Seix Barral, 1964; 2nd ed., Seix Barral; 1975, 3rd ed., in: Existential Analysis. Essays, Triacastela Publishing House, 2004). In this case, the most convenient and least stimulating editorial option has been chosen: it is a text very well known by those interested in the subject, with little chance of sparking interest beyond them. The new edition includes as an appendix the important prologue that Castilla del Pino prepared for the first edition, reproduced in all subsequent editions and since then determining the “received vision” of Martín-Santos as a psychiatrist. It also includes a prologue by Manuel Villegas Besora, which recycles, with few variations, his 1985 article The Significance of Martín-Santos’ Work for the History of Spanish Psychology and Psychiatry. This text is reliable, informative, and useful for the reader unfamiliar with the context of the text presented, despite some surprising slip-ups: Martín-Santos, like all his contemporary psychiatrists, had the historic opportunity to witness the emergence of the new psychopharmaceuticals that in less than ten years managed to completely transform the treatment of mental illnesses and became the basis of those still used today: lithium salts (1949), chlorpromazine (1952), reserpine (1952), iproniazid (1957), imipramine (1957), or chlordiazepoxide (1959), among others. That is, the first mood stabilisers, neuroleptics, antidepressants, and anxiolytics from which practically all current psychopharmacology derives. This therapeutic revolution was experienced first-hand by him, who in his early articles had recorded the resources he used: today considered low-efficacy drugs, lots of electroshock, and, on some unfortunate occasions, psychosurgery. His reading of Freud was late, and his practice of “existential psychoanalysis” seems to have been even later. Villegas Besora asserts, with clear intent, that those new drugs from the 1950s came “from American laboratories.” The truth is that lithium salts were introduced by John Cade from the Australian hospital where he worked, and all the other molecules mentioned come from research conducted in French or Swiss laboratories: Rhône-Poulenc, Ciba, Hoffmann-La Roche, Geigy…

In short, with its many lights and few shadows (for the moment), these nascent Complete Works of Martín-Santos are a commendable—and brave—editorial initiative that, if it manages to come to fruition, will enrich our understanding to such an extent that the cliché of the “brilliant author of a single novel” will give way, despite his short life, to a prolific author (albeit posthumously) with a heterogeneous and torrential body of work. The large tribe of academics who have spent sixty years going round and round “Tiempo de silencio” will find themselves with an unexplored ocean from which many and very diverse surprises can be expected.

Conflict of interestNone to declare.

1. Lázaro J. Vidas y muertes de Luis Martín-Santos, Barcelona, Tusquets; 2009.

2. Martín-Santos L. Dilthey, Jaspers y la comprensión del enfermo mental. Madrid:Paz Montalvo; 1955.

3. Martín-Santos L. [Edición de José Lázaro] El análisis existencial. Ensayos. Madrid, Editorial Triacastela; 2004.

4. Martín-Santos L. [Edición dirigida por Domingo Ródenas de Moya] Obras comple-tas I. Narrativa breve, Barcelona, Galaxia Gutenberg; 2024.

5. Martín-Santos L. [Edición dirigida por Domingo Ródenas de Moya] Obras com-pletas II. Libertad, temporalidad y transferencia en el psicoanálisis existencial, Barcelona, Galaxia Gutenberg; 2024.