Performance information is credible when it assists in accurately assessing departments’ progress towards the achievement of their goals—the cornerstone of performance reporting. In South Africa it is a legislated requirement for government departments to report annually on the performance of the entity against predetermined objectives. The purpose of this paper is to perform a qualitative analysis of the reporting of performance against pre-determined objectives by national government departments and to determine by comparison whether national government departments in South Africa have improved in the quality of the reporting of their performance information from the 2009/10 to the 2010/11 financial years. The objective of the audit of performance information by the AGSA is to determine whether the reported performance of a government department is useful, reliable and compliant to legislative and other official requirements. The results of this study clearly indicate that there are still major deficiencies in the reporting of performance information and that there was no material improvement from the 2009/10 to the 2010/11 financial years.

“Industrial country democracies have shifted away from traditional forms of accountability towards accountability based on performance and the quality of services rendered by government” (Peters, 2007). Public service organisations should be service delivery driven. The impact of the spending of public money should be measurable and the public service should be accountable for its spending and performance. Performance information is often used to determine further spending and other public service interventions. The reliability of the performance information reported is thus of very high importance.

In South Africa it is a legislated requirement for government departments to report annually on the performance of the entity against predetermined objectives (AGSA, 2010: 1). However, reporting this non-financial information on service delivery performance still proves to be a challenge for many organs of state. The Applied Fiscal Research Centre (AFReC, 2010) at the University of Cape Town is of the opinion that government departments often provide the performance information reports very late in the service delivery process. It has also been determined that the information in the reports is often inaccurate and cannot be validated.

The South African government allowed its performance reporting process to evolve over the past decade (Engela & Ajam, 2010: V). It has been foreseen for some time that an independent opinion would be expressed whether the reported performance of a government department is a fair representation of the actual performance against the pre-determined objectives of the department. The Auditor-General (South Africa's Supreme Audit Institution) has been phasing in the expression of audit opinions based on Audits of Performance Information and it will ultimately lead to an opinion expressed on the audit report of a department, alongside the opinion on the financial statements. It was seen, in 2010, as an opportune time to perform an adequacy and compliance analysis of the 2009/10 audit reports on performance against predetermined objectives for South African national government departments (Erasmus & van der Nest, 2011).

The purpose of this paper is to perform a qualitative analysis of the reporting of performance against pre-determined objectives by national government departments and to determine by comparison whether national government departments in South Africa have improved in the quality of the reporting of their performance information from the 2009/10 to the 2010/11 financial years. The paper also identifies the specific areas where shortcomings have been identified.

2The development of performance reporting2.1International developmentThe measurement and disclosure of performance have a documented history in European public administration and public management. In the 1930s Clarence Ridley and Herbert Simon (cited by Johnson, 2000: 6) studied efficiency by measuring municipal activities, and elaborated on the utilisation of performance reviews. In the United States of America, performance measurement has been a priority of public administration since the early twentieth century (Gianakis, 2002: 37). Heinrich (2004: 317) is of the opinion that although performance measurement as a management tool dates back to the 1800s, it is only in the last two decades that public sector performance management adopted an explicit focuses on measuring outcomes.

Although there are differing views on when performance measurement and disclosure commenced, in fact, it is clear that performance measurement in whichever form has become a global phenomenon, as it promises professional public sector management. According to Terry, cited by Gianakis (2002: 36), the public sector performance measurement phenomenon is international in its scope and is the centrepiece of what has become known as the “new public management” (Moynihan, 2006; Moynihan, 2006: 77; Cortes, 2005: 2), or the “new public sector” (Brignall & Modell, 2000; Sanderson, 2001: 297).

The “new public management” endeavours to achieve performance measurement according to private business principles for improved transparency and accountability of management, in the use of public resources (Alam & Nandan, 2005: 2; Berland & Dreveton, 2005: 4; Brusca & Montesinos, 2005: 2; Christiaens & Van Peteghem, 2005: 5; Rommel, 2005: 3). Performance measurement is defined by Kerssens-van Droggelen, cited by Roth (2002) as “…that part of the control process that has to do with the acquisition and analysis of information about the actual attainment of company objectives and plans (read predetermined objectives), and about factors that may influence plan realisation.” Consequently, performance measurement assesses the accountability for the use of public resources (Schacter, 2002: 5). To assess accountability, service delivery has to be reviewed, but in order for service delivery to be reviewed, details need to be disclosed.

In recent times many international scholarly articles and government reports have been written on aspects of governmental performance reporting. Canada in particular has a well established system of performance reporting that states that performance reporting is closely linked to the responsibilities that are commonly associated with good governance (CCAF-FCVI, 2001: 6). A number of reports from Canada indicate a well researched and guided system of governmental performance reporting (CCAF-FCVI, 2007, 2008). In British Columbia (Canada), a report by The Office of the Auditor General of British Columbia (2008: 43–44) presents the first comprehensive survey of the quality of performance measures contained in the annual report. According to this the quality of performance measures in an annual report is a key determinant of the efficacy of that report. The findings of the report provide an encouraging picture of maturity of performance reporting in British Columbia, with performance measures consistently meeting the “SMART” criteria for good performance measures – Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Reliable and Time-bound.

In the United States of America the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 requires that federal agencies identify how they will measure outcomes, set predetermined objectives and produce annual performance reports (Ellig, 2007: 3). According to Ellig and Wray (2008: 64) their Congress required the first annual performance reports in 1999. Between 2002 and 2007 most agencies produced annual performance and accountability reports that combined performance and financial data. In the United Kingdom, McAdam and Saulters (2000) write that since 1968, there has been a consistent call for more effectual performance reporting, which will enable a meaningful assessment to be drawn up of an entity's overall performance.

It is clear that the abovementioned countries have a history in performance reporting and in some measure they have been successful. What emerges clearly from many papers is that numerous challenges arise during the implementation phase (GAO, 2000, 2002; CCAF-FCVI, 2006), and that performance reporting, even in countries with established systems, is subjected to continuous scrutiny with a view to improvement.

2.2The development of the process in South AfricaOne of the key priorities of the newly elected South African government of 1994 was to enhance access to and improve the quality of services delivered to previously under-sourced communities. The South African Constitution demands effective and accountable stewardship of public resources, as well as effective oversight by Parliament, amongst others (SA, 1996). In response to this the South African government embarked on a road of public sector reform that included budget reforms. These budget reforms initially focussed on public expenditure management, but with the clear objective of evolving this system into a fully functional performance budgeting system, in pursuit of value-for-money spending (Engela & Ajam, 2010: 2).

Laws have been promulgated to ensure that a performance management process be implemented. As far back as 2000, the Public Finance Management Act (PFMA) required that National Government Departments submit predetermined measurable objectives to Parliament for each main service delivery programme on the introduction of the annual budget (SA, 2000: Sec 27(4)). These pre-determined objectives were to be pursued through the performance management process that is guided by the frameworks of the National Treasury.

Since the concept of performance budgeting was legislated and regulated, a number of frameworks and guidance documents have been issued by the National Treasury to guide National Departments in the implementation of this performance management process. Documents included among others “Budgeting Planning and Measuring Service Delivery” (NT, 2001), “In-year monitoring and reporting” (NT, 2000), “Framework for Managing Programme Performance Information” (NT, 2007), and the latest “Framework for Strategic Plans and Annual Performance Plans” (NT, 2010a, 2010b).

This sustained guidance provided by the National Treasury is indicative of the South African government's insistence on a fully functional performance management process. According to Engela and Ajam (2010: V), the South African government allowed its monitoring and reporting system development to evolve, rather than follow a detailed blueprint. Furthermore capacity and system building were deemed as a first priority with a conscious decision to pursue evaluation at a later stage. For the evaluation to be rated as credible, the performance information reported will have to be subjected to an independent verification process (read audit).

However, even though some guidance was provided, up to 2005 no reporting framework existed for the preparation of departmental performance information (Erasmus, 2008: 93). This reporting framework had to receive attention as the Public Audit Act, Act 25 of 2004 (South Africa, 2004) Section 20 (2)(c) states specifically that an audit report at the very least needs to reflect an opinion on, or draw conclusions from reported information, relating to the performance of the auditee against predetermined objectives. This requirement of the Act necessitated that the Auditor-General South Africa (AGSA) revisit his strategy and approach to the audit of performance information in 2007. In the government gazette of 25 May 2007 (SA, 2007: 10), a directive in terms of the Public Audit Act, was issued by the AGSA. A phasing-in approach to the audit of performance information should be followed, until the environment had matured to provide reasonable assurance in the form of an audit opinion. According to the Auditor-General (SA, 2010: 4) “the audit of reporting against predetermined objectives has been phased in over a couple of years and has now reached a stage of maturity”. Although an audit opinion was not expressed in the 2009/10 financial year, material findings were reported in the “Report on other legal and regulatory requirements” section of the audit report of a department, after an audit readiness assessment by the Auditor-General it was again decided not to express an opinion on the reported performance information of government departments in the 2010/11 financial year. Findings on performance information were however again reported on the face of the audit reports of individual departments. These are the reports that were sourced and analysed to meet the objectives of this study.

3Objective and methodologyThis study is in essence a qualitative content analysis. Silverman (2008: 377) states that a qualitative analysis of the content of texts and documents, such as annual reports, constitutes a qualitative content analysis. The qualitative analysis is presented at the hand of descriptive statistics spanning two financial years. An analysis was performed of 31 audit reports of national government departments (97% of population for 2009/10 and 80% of the population for 2010/11). The first analysis was performed on the 2009/10 audit reports form the Auditor-General as contained in the annual reports of the various national government departments (Erasmus and van der Nest, 2011). During the 2010/11 financial year, seven new national government departments were established in South Africa and were audited by the Auditor-General. For ease of comparison the audit reports of the same departments that were analysed for the 2009/10 financial year were again analysed for 2010/11. The focus was on the reporting of performance against predetermined objectives (performance information). The chief objective was to determine, through qualitative analysis whether the performance information reported in the annual reports of national government departments was reliable and adequate and to measure the change, either positive or negative over the two consecutive financial years. The study further aimed to determine whether compliance with the prescribed formats for the reporting of performance information was evident.

4Legal and regulatory framework within which performance information is reportedSince 1994, the National Treasury has emphasised and pursued reform of overall public financial management to effect transformation in public service delivery. An urgent need for more efficient, effective and economical spending was identified. This gave rise to the change from an input-based budgeting system (line-item/programme budgeting) to an output-based, results orientated system (multi-year programme budgeting and performance budgeting). To measure actual performance against predetermined objectives a performance management process had to be implemented. However, this process first had to be formalised in legislation.

The Treasury Regulations (NT, 2005: chap. 5) and Public Service Regulations (South Africa (DPSA), 2001: Part III B.1 (a)–(e), (g)) require that each National Department prepare a strategic plan for the forthcoming medium-term budgeting period. The strategic plan needs, among other things, include predetermined measurable objectives, expected outcomes, programme outputs, indicators (measures) and targets of the department's programmes. The strategic plan should form the basis of the annual reports as required by sections 40(1) (d) and (e) of the PFMA (SA, 2000).

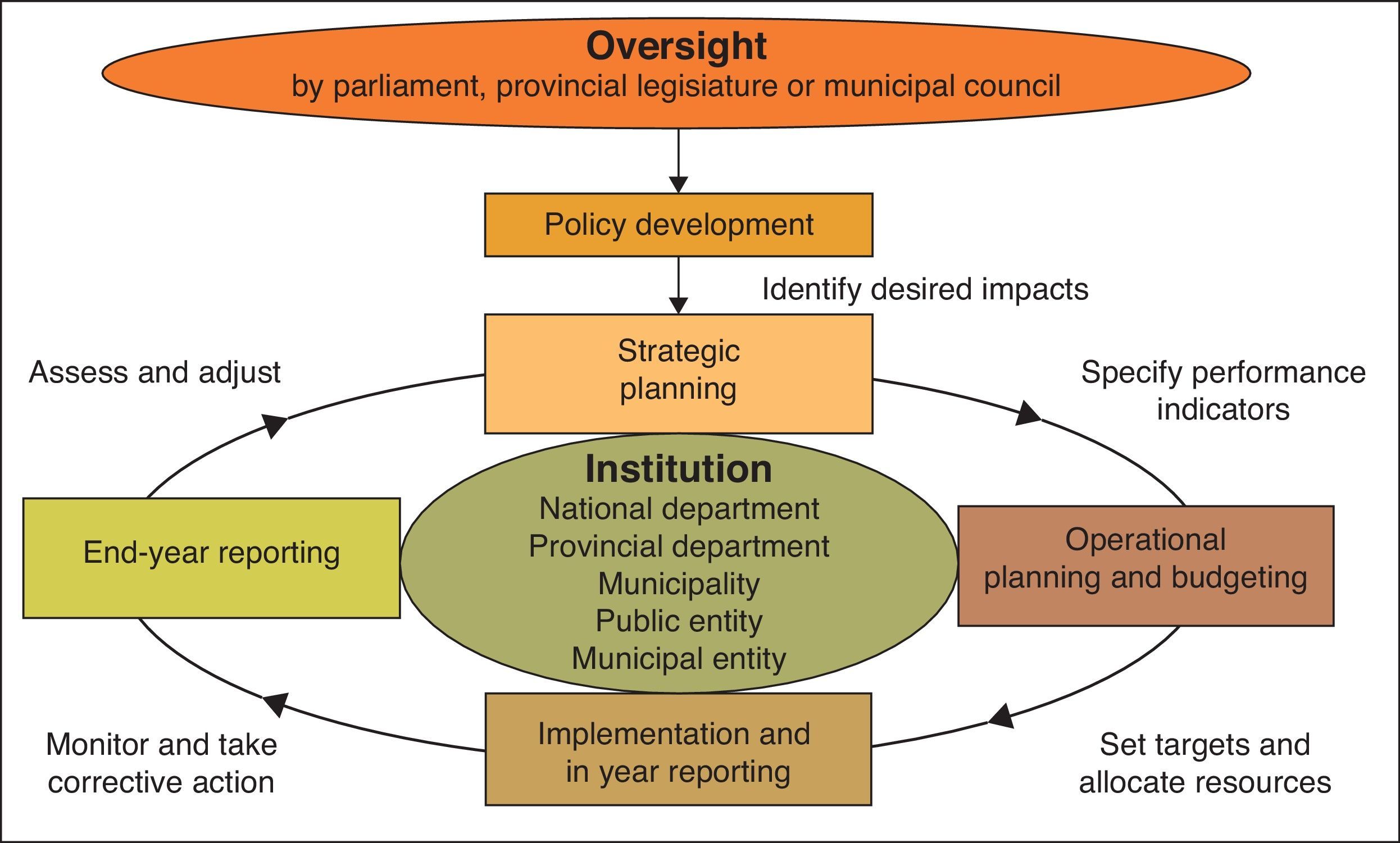

A further requirement stipulated by the PFMA (SA, 2000: Sec 40 (3)) is that this annual report should present a fair reflection of a department's performance as measured against predetermined objectives. The Treasury Regulations (NT, 2005: chap. 18.3.1(b)) supporting the PFMA require that in preparing the annual report, information on the department's efficiency, economy and effectiveness in delivering programmes and achieving its objectives must be included, as well as outcomes against the measures and indicators set out in any strategic plan for the year under consideration. Procedures need to be formulated for quarterly reporting to the executive authority to facilitate effective performance monitoring, evaluation and corrective action (NT, 2005: chap. 5.3.1) of the measurable objectives that are to be submitted with the annual budget (SA, 2000: Sec 27(4)). As a result of the above legislation the South African government has implemented a performance management process that is graphically presented in Fig. 1.

The above performance management process is referred to by the National Treasury as the planning, budgeting and reporting cycle. Two recent frameworks issued by the National Treasury provide guidance for departments on the use of this cycle. The Framework for Managing Programme Performance Information was published in 2007 and the Framework for Strategic Plans and Annual Performance Plans was published in 2010, although these are merely refined versions of those that have been available since 2000.

In the Framework for Managing Programme Performance Information (NT, 2007) the National Treasury aims to clarify definitions and spell out standards for performance information in support of regular audits of such information, to improve the structures, systems and processes required to manage performance information, to define roles and responsibilities for managing performance information. Accountability and transparency will be promoted by providing timely, accessible and accurate performance information to all stakeholders.

This Framework for Strategic Plans and Annual Performance Plans (NT, 2010a, 2010b) outlines the key concepts to guide National Departments when developing Strategic Plans and Annual Performance Plans. It provides guidance on good practice and budget-related information requirements in support of generation, gathering, processing and reporting on performance information.

The strategic planning process with its link to measurable objectives, setting performance targets and costing these intended outputs by government departments is explained and set out in treasury guidelines published annually. Within the annual budgeting process, details of budgets and the objectives it supports are discussed at various forums between government departments and their treasuries. Reporting on past performance of programmes is also scrutinised by the National Treasury in conjunction with planned performance for the coming period, when taking budget allocation decisions (NT, 2010a, 2010b: 5). As a result of this vigorous review process followed in approving budget allocations based on performance targets and measurable objectives, it may be assumed that the measurable objectives and performance targets set in the approved Annual Performance Plan (First year of the Strategic Plan) of a government department were deemed acceptable (useful, reliable and compliant) by both the senior management of the department, as well as their relevant treasuries. These aspects will certainly be important to the users of performance information.

5Users of performance informationCitizens are often denied opportunities to monitor the actual delivery of services, this is regardless of their degree of involvement in the policy or budget planning and decision stages (Russel-Einhorn, 2007).

Performance information is credible when it assists in accurately assessing departments’ progress towards the achievement of their goals—the cornerstone of performance reporting (U.S. General Accounting Office, 2000: 7). The AGSA (2010: 1) states that the performance reports of government departments are mainly used by Parliament, Provincial Legislators, elected officials, National and Provincial Treasuries and members of the public. This information is used to determine the success of government in terms of service delivery and the prudent use of taxpayers’ money. As a result is it important that an independent opinion is obtained on the credibility (usefulness, reliability and compliance) of the performance information.

6Audit of performance information6.1FrameworkThe audit functions of the AGSA are performed in terms of the Public Audit Act (South Africa, 2004). Section 52(1) of the Public Audit Act specifically authorises the AGSA to publish, in the government gazette, the functions that will be performed in a financial year. The audit functions for the audit of the 2009/10 financial year were published in the Government Gazette, nr 33872 (SA, 2010). The framework within which the audit will be performed is; all relevant laws and regulations, the Framework for the Managing of Programme Performance Information and other relevant frameworks, as well as circulars and Treasury guidance (SA, 2010: 3). In 2011 the Auditor-General (SA, 2011: 5) indicated that “the audit of performance against predetermined objectives is performed in accordance with the International Standard on Assurance Engagements (ISAE) 3000 Assurance engagements other than audits or reviews of historical financial information against the Performance management and reporting framework, consisting of applicable laws and regulations, the Framework for the managing of programme performance information issued by the National Treasury and circulars and guidance issued by the National Treasury regarding the planning, management, monitoring and reporting of performance against predetermined objectives. According to the Auditor-General (2011: 23), they have gradually been phasing in the auditing of reporting against the pre-determined objectives in the strategic plan from the 2005/6 financial year.

6.2Audit objective and approachThe objective of the audit of performance information by the AGSA is to determine whether the reported performance of a government department is useful, reliable and compliant to legislative and other official requirements. As indicated in Section 2.2 above, an audit opinion was not be expressed in the 2009/10 and 2010/11 financial years and any material findings were reported in the “Report on Other Legal and Regulatory Requirements” section of the audit report of a department. In addition, a conclusion on the performance against predetermined objectives was included in the management report of departments (AGSA, 2010: 4). It should be clear that the audit of reporting against predetermined objectives forms part of the regularity audit of departments. It should not be confused with performance auditing. The purpose is thus not to express an opinion over the performance of the department, but the quality of the reporting of performance.

The AGSA's approach to the audit of predetermined objectives in the financial years under review was to:

- •

“Understand the internal policies, procedures and controls related to the management of performance information.

- •

Understanding and testing the systems and controls relevant to the recording, monitoring and reporting of performance information.

- •

Verifying the existence, measurability and relevance of planned and reported performance information.

- •

Verifying the consistency of performance information between the strategic or annual performance or integrated development plan, quarterly or mid-year report and the annual performance report.

- •

Verifying the presentation of performance against predetermined objectives in the annual performance report against the format and content requirements determined by the National Treasury.

- •

Comparing reported performance information to relevant source documents, and verifying the validity, accuracy and completeness thereof” (AGSA, 2010: 2).

Although a detail assessment of the findings by the AGSA is discussed in paragraph 7 below, the findings have been grouped in general under; non-compliance with regulations and frameworks, usefulness of performance information and reliability of performance information.

7Result of the qualitative content analysis of the audit reports7.1Validation of survey resultA descriptive analysis of the information obtained is reflected below. The indications of findings and categories of findings for the two financial years 2009/2010 and 2010/2011are indicated in table format for ease of reference.

7.1.1Data formatThe data was received in excel format which was manipulated and imported into SAS format to do the various statistical tests on it. Each of the variables indicating whether there were findings and which categories are involved are dichotomous variables. Thus this is categorical data and of the nominal type.

7.1.2Data validationThe reliability of the items in this analysis; were measured by using the Cronbach Alpha tests. A frequency analysis was performed on all the variables; displaying frequencies, percentages, cumulative frequencies and cumulative percentages. The Cronbach's Alpha Coefficients for each item was more than 0.70 (the acceptable level according to Nunnally, 1978: 245), and thus these items prove to be reliable and consistent for all the items in the two scales for both financial years.

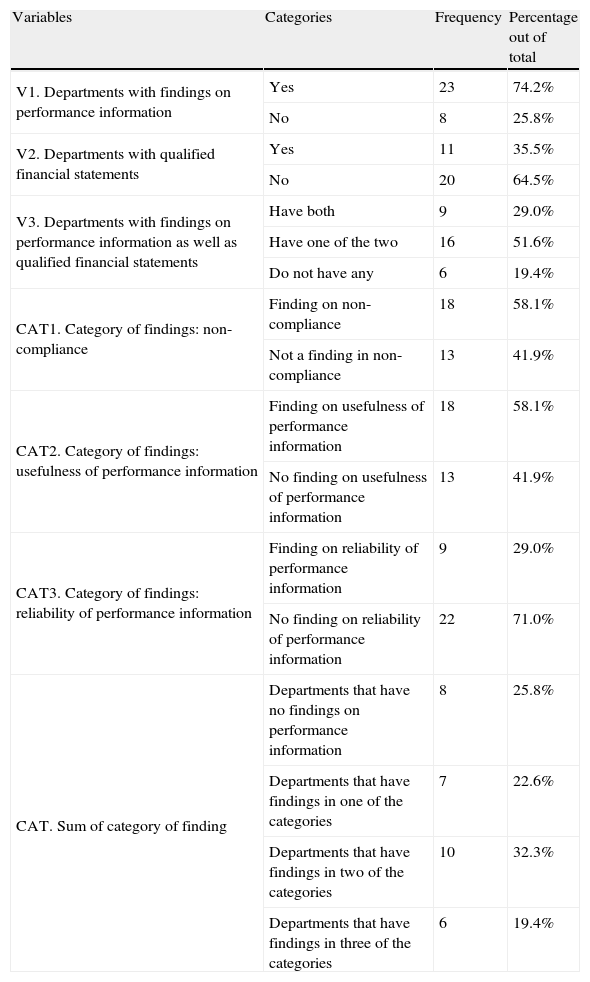

7.2Research findings7.2.1Descriptive statisticsTable 1 shows the descriptive statistics for all the variables and for all the departments in 2009/2010 in the survey with the frequencies in each category and the percentage out of total number of departmental audit reports reviewed. Take note that the descriptive statistics are based on the total sample (all the departments that were analysed). Table 2 indicates only those departments that had findings on performance information in 2009/2010.

Descriptive statistics on research variables for total sample 2009/2010.

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage out of total |

| V1. Departments with findings on performance information | Yes | 23 | 74.2% |

| No | 8 | 25.8% | |

| V2. Departments with qualified financial statements | Yes | 11 | 35.5% |

| No | 20 | 64.5% | |

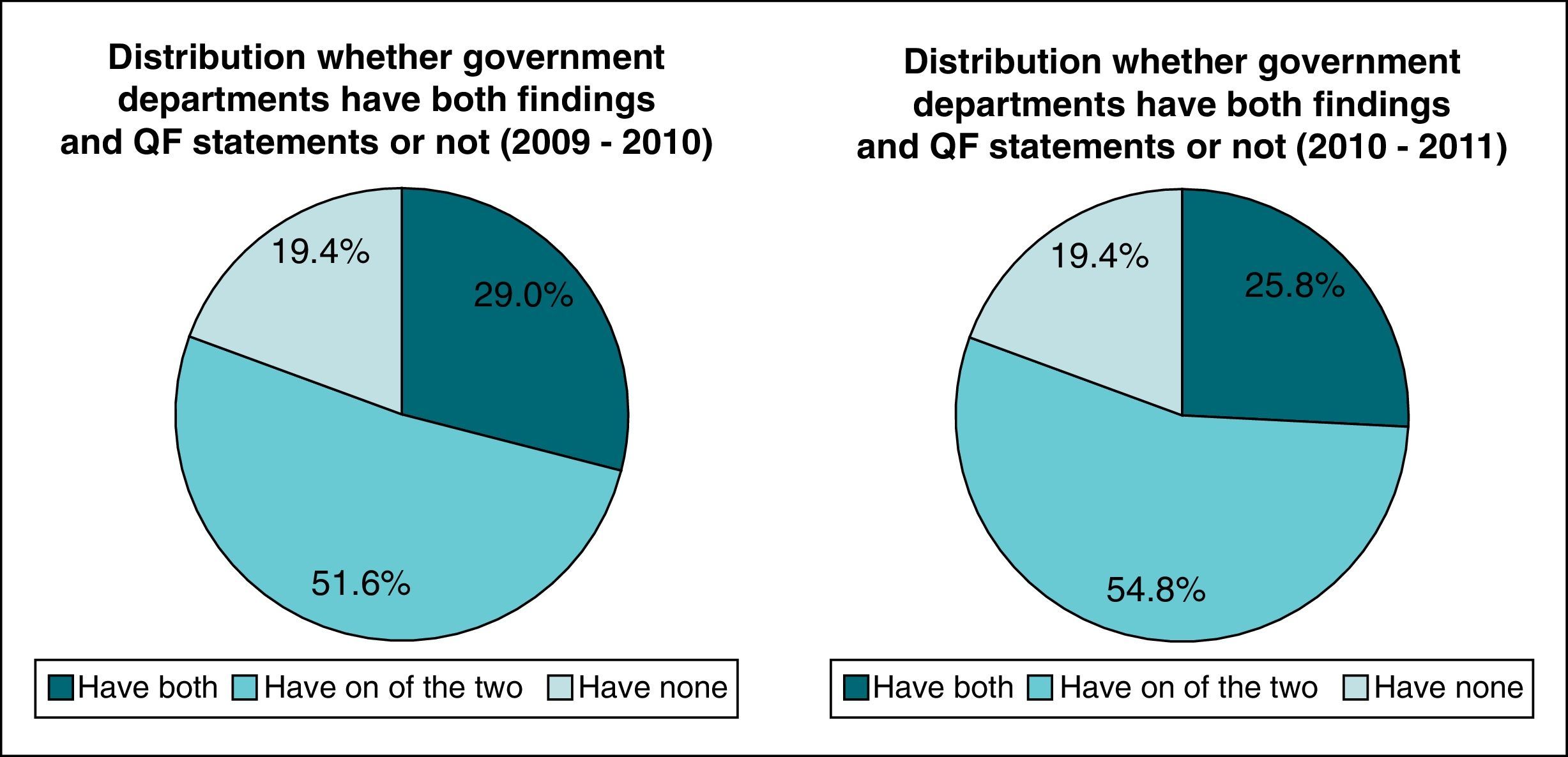

| V3. Departments with findings on performance information as well as qualified financial statements | Have both | 9 | 29.0% |

| Have one of the two | 16 | 51.6% | |

| Do not have any | 6 | 19.4% | |

| CAT1. Category of findings: non-compliance | Finding on non-compliance | 18 | 58.1% |

| Not a finding in non-compliance | 13 | 41.9% | |

| CAT2. Category of findings: usefulness of performance information | Finding on usefulness of performance information | 18 | 58.1% |

| No finding on usefulness of performance information | 13 | 41.9% | |

| CAT3. Category of findings: reliability of performance information | Finding on reliability of performance information | 9 | 29.0% |

| No finding on reliability of performance information | 22 | 71.0% | |

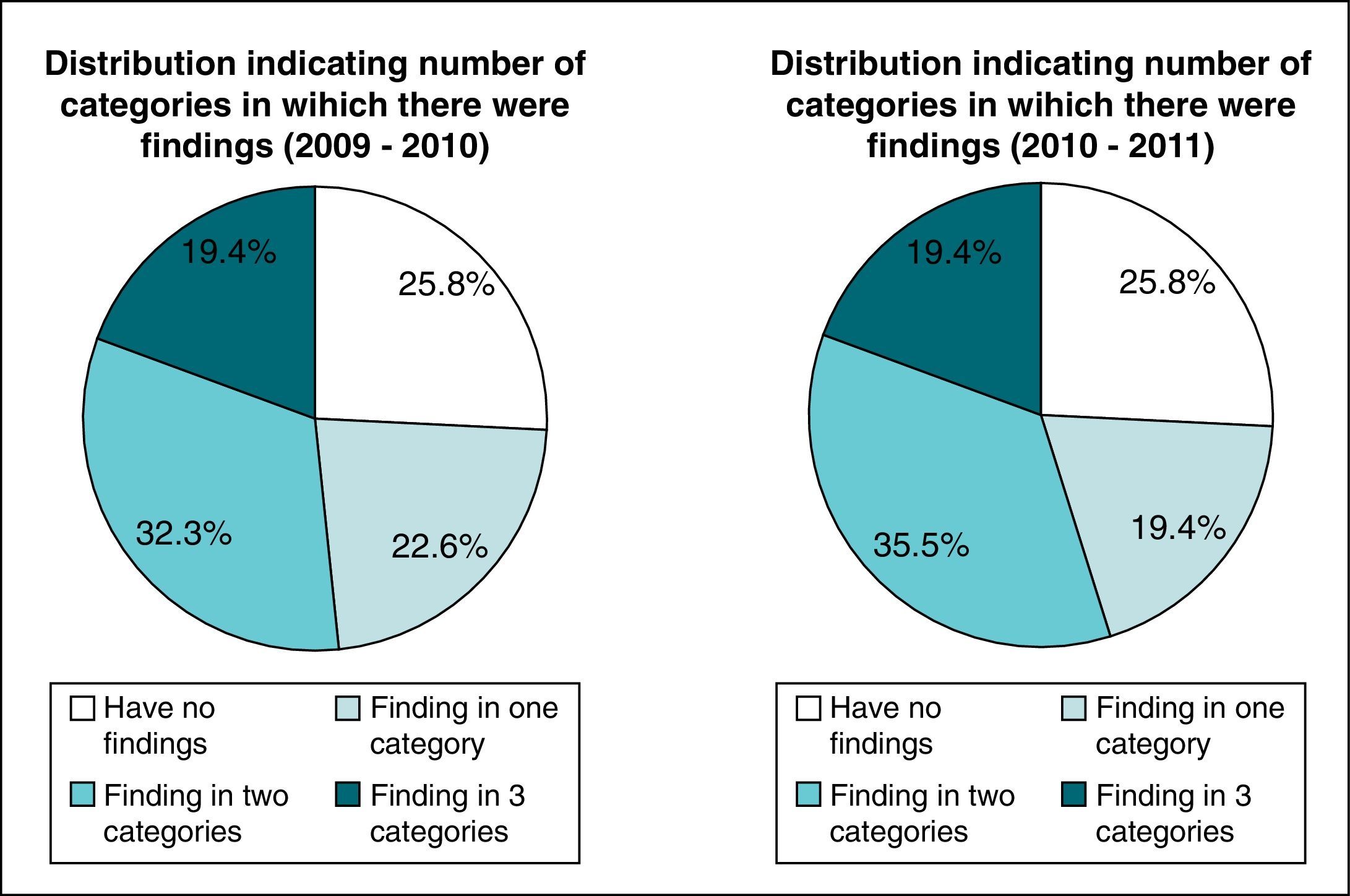

| CAT. Sum of category of finding | Departments that have no findings on performance information | 8 | 25.8% |

| Departments that have findings in one of the categories | 7 | 22.6% | |

| Departments that have findings in two of the categories | 10 | 32.3% | |

| Departments that have findings in three of the categories | 6 | 19.4% |

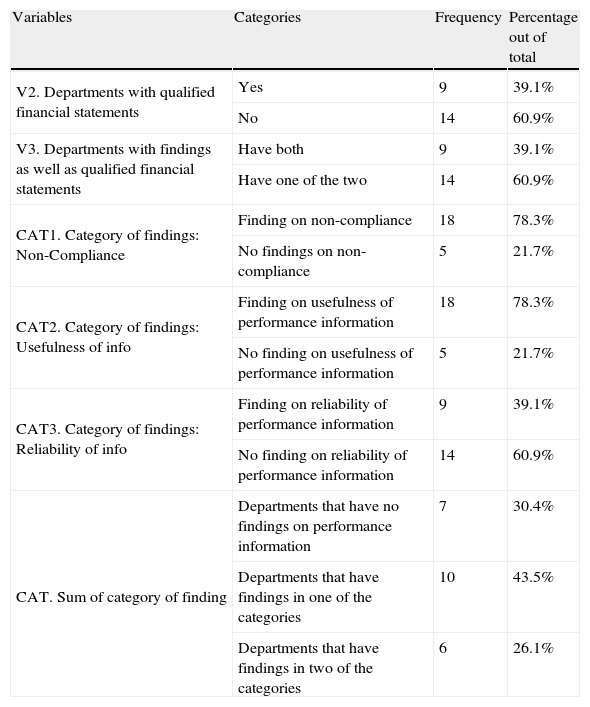

Descriptive statistics on research variables for departments with findings on performance information for 2009/2010.

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage out of total |

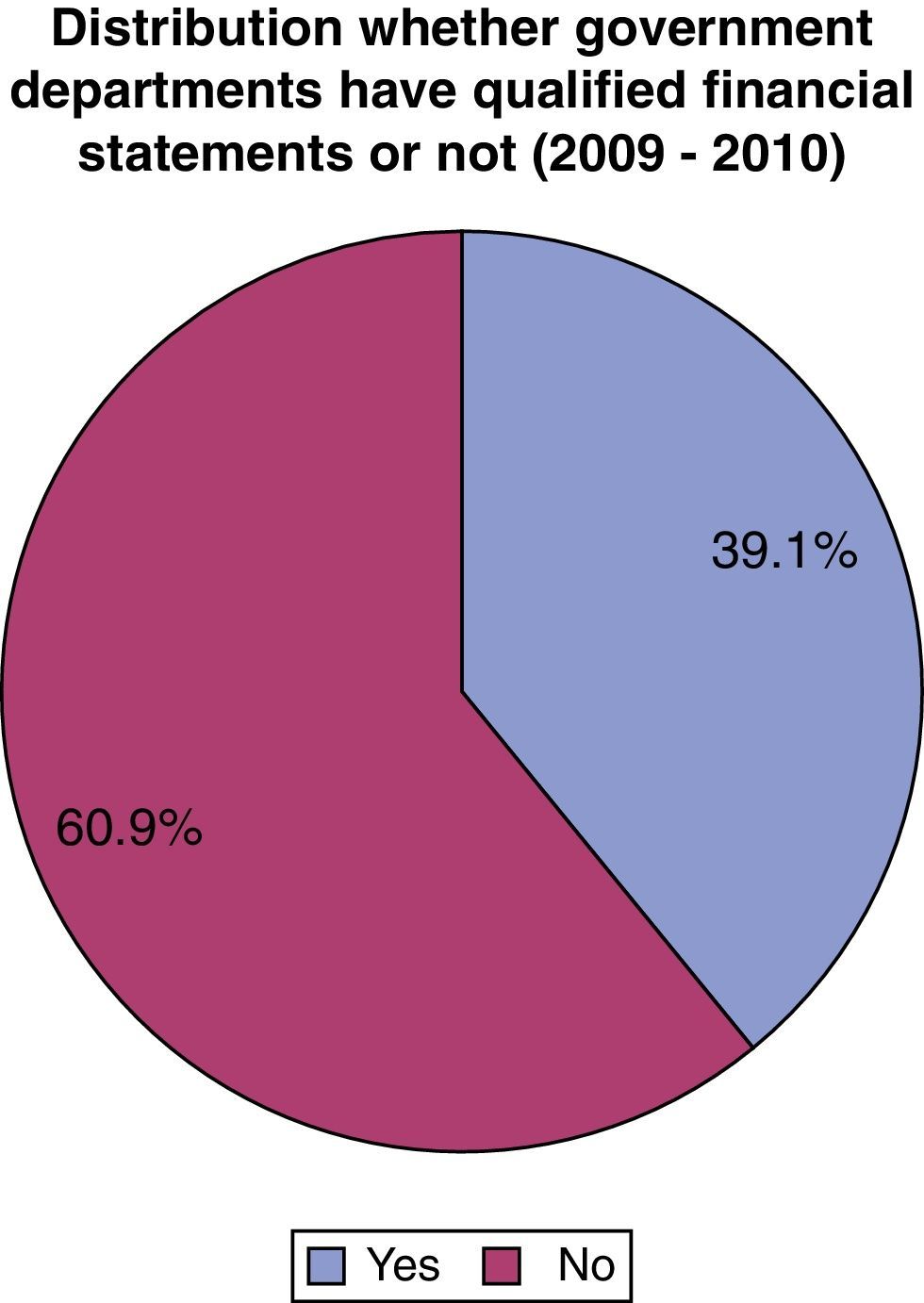

| V2. Departments with qualified financial statements | Yes | 9 | 39.1% |

| No | 14 | 60.9% | |

| V3. Departments with findings as well as qualified financial statements | Have both | 9 | 39.1% |

| Have one of the two | 14 | 60.9% | |

| CAT1. Category of findings: Non-Compliance | Finding on non-compliance | 18 | 78.3% |

| No findings on non-compliance | 5 | 21.7% | |

| CAT2. Category of findings: Usefulness of info | Finding on usefulness of performance information | 18 | 78.3% |

| No finding on usefulness of performance information | 5 | 21.7% | |

| CAT3. Category of findings: Reliability of info | Finding on reliability of performance information | 9 | 39.1% |

| No finding on reliability of performance information | 14 | 60.9% | |

| CAT. Sum of category of finding | Departments that have no findings on performance information | 7 | 30.4% |

| Departments that have findings in one of the categories | 10 | 43.5% | |

| Departments that have findings in two of the categories | 6 | 26.1% |

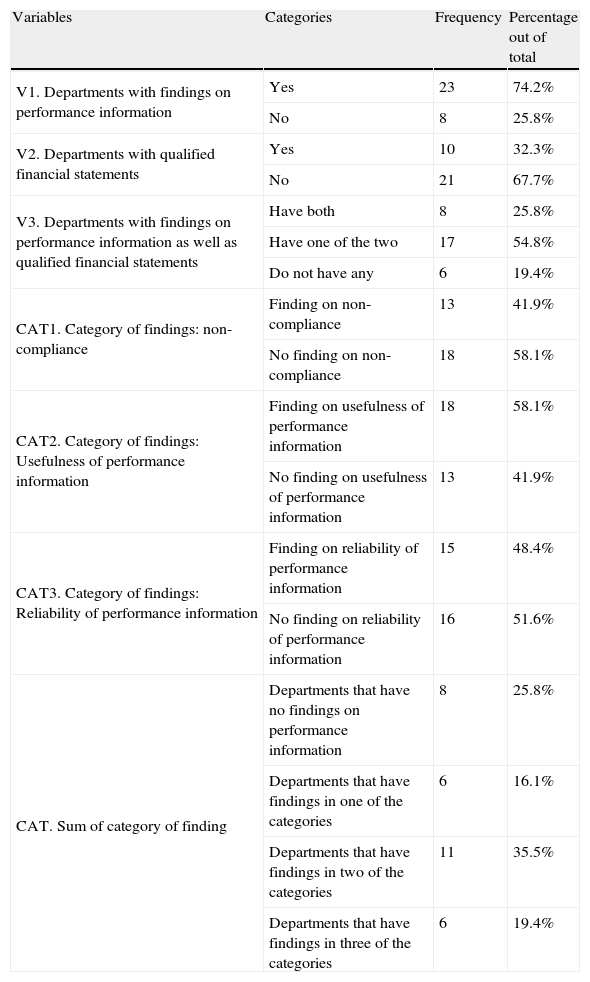

Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics for all the variables and for all the departments in 2010/2011 in the survey with the frequencies in each category and the percentage out of total number of responses. Take note that the descriptive statistics are based on the total sample (all the departments that were analysed). Table 4 indicates only those departments that had findings on performance information in 2010/2011.

Descriptive statistics on research variables for total sample 2010/2011.

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage out of total |

| V1. Departments with findings on performance information | Yes | 23 | 74.2% |

| No | 8 | 25.8% | |

| V2. Departments with qualified financial statements | Yes | 10 | 32.3% |

| No | 21 | 67.7% | |

| V3. Departments with findings on performance information as well as qualified financial statements | Have both | 8 | 25.8% |

| Have one of the two | 17 | 54.8% | |

| Do not have any | 6 | 19.4% | |

| CAT1. Category of findings: non-compliance | Finding on non-compliance | 13 | 41.9% |

| No finding on non-compliance | 18 | 58.1% | |

| CAT2. Category of findings: Usefulness of performance information | Finding on usefulness of performance information | 18 | 58.1% |

| No finding on usefulness of performance information | 13 | 41.9% | |

| CAT3. Category of findings: Reliability of performance information | Finding on reliability of performance information | 15 | 48.4% |

| No finding on reliability of performance information | 16 | 51.6% | |

| CAT. Sum of category of finding | Departments that have no findings on performance information | 8 | 25.8% |

| Departments that have findings in one of the categories | 6 | 16.1% | |

| Departments that have findings in two of the categories | 11 | 35.5% | |

| Departments that have findings in three of the categories | 6 | 19.4% |

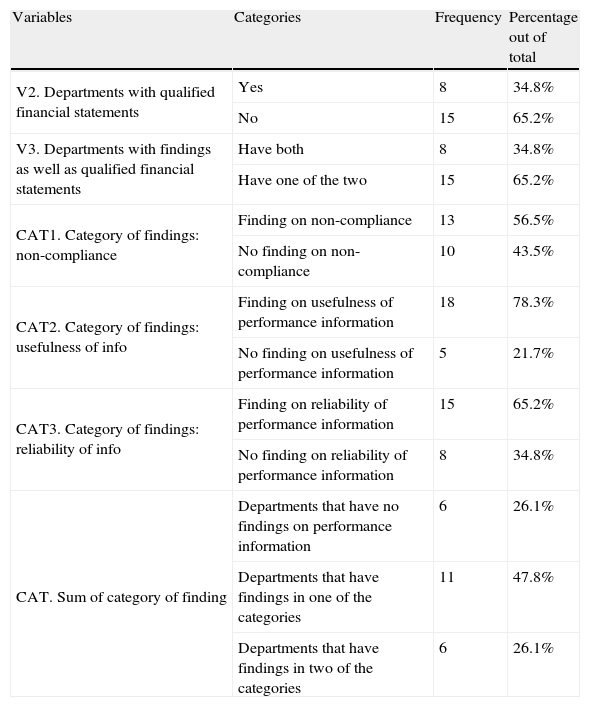

Descriptive statistics on research variables for departments with findings on performance information for 2010/2011.

| Variables | Categories | Frequency | Percentage out of total |

| V2. Departments with qualified financial statements | Yes | 8 | 34.8% |

| No | 15 | 65.2% | |

| V3. Departments with findings as well as qualified financial statements | Have both | 8 | 34.8% |

| Have one of the two | 15 | 65.2% | |

| CAT1. Category of findings: non-compliance | Finding on non-compliance | 13 | 56.5% |

| No finding on non-compliance | 10 | 43.5% | |

| CAT2. Category of findings: usefulness of info | Finding on usefulness of performance information | 18 | 78.3% |

| No finding on usefulness of performance information | 5 | 21.7% | |

| CAT3. Category of findings: reliability of info | Finding on reliability of performance information | 15 | 65.2% |

| No finding on reliability of performance information | 8 | 34.8% | |

| CAT. Sum of category of finding | Departments that have no findings on performance information | 6 | 26.1% |

| Departments that have findings in one of the categories | 11 | 47.8% | |

| Departments that have findings in two of the categories | 6 | 26.1% |

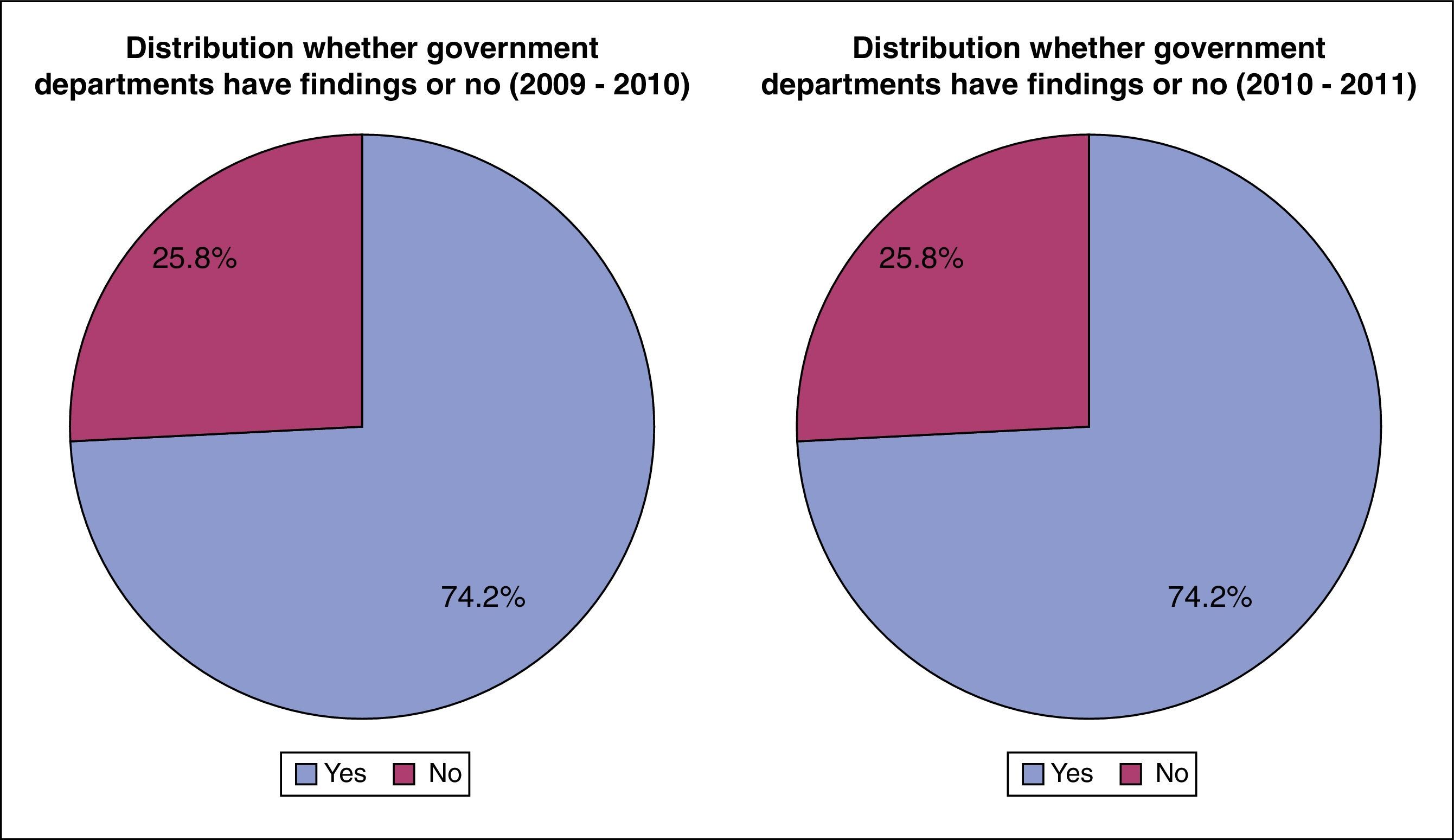

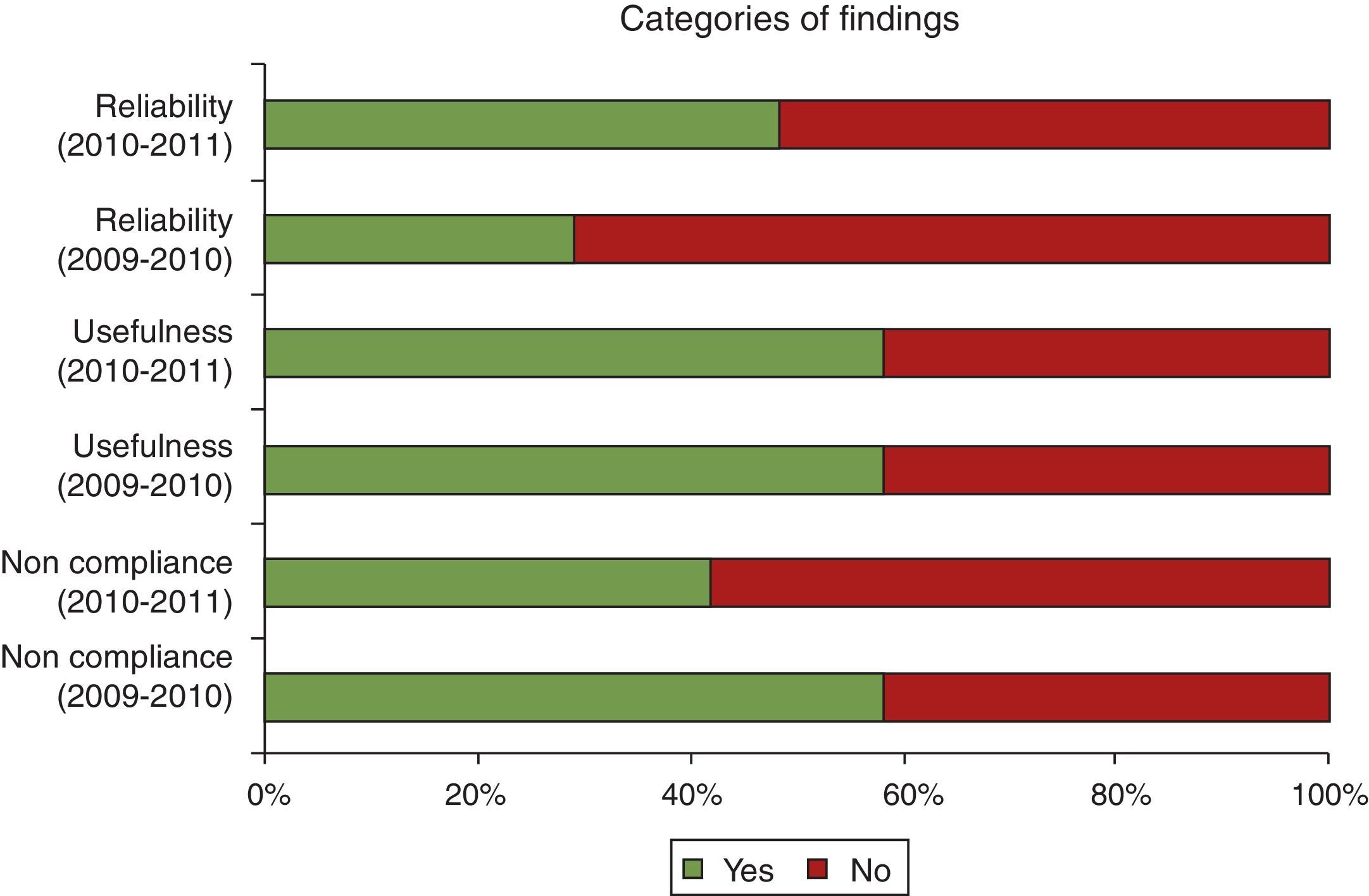

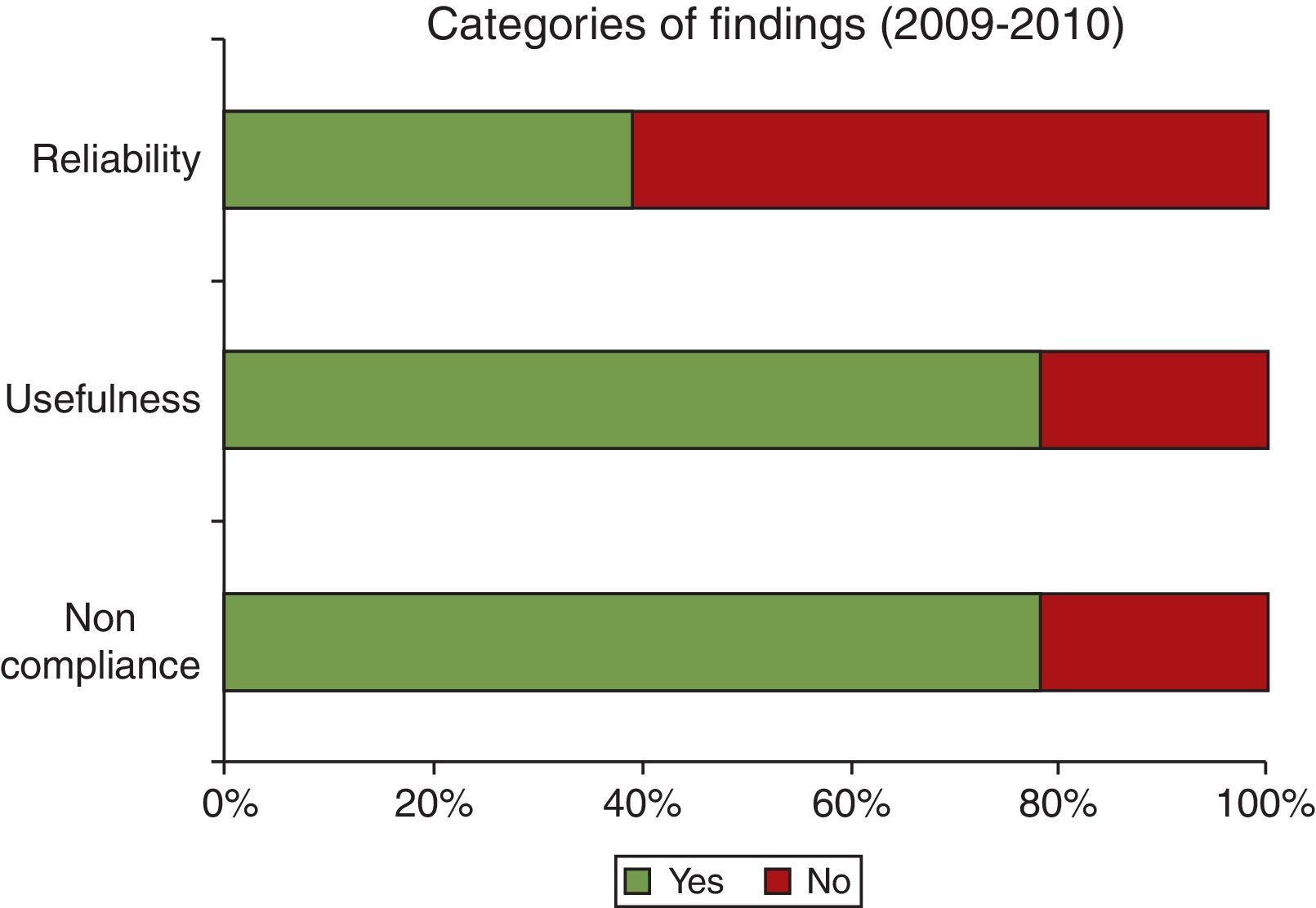

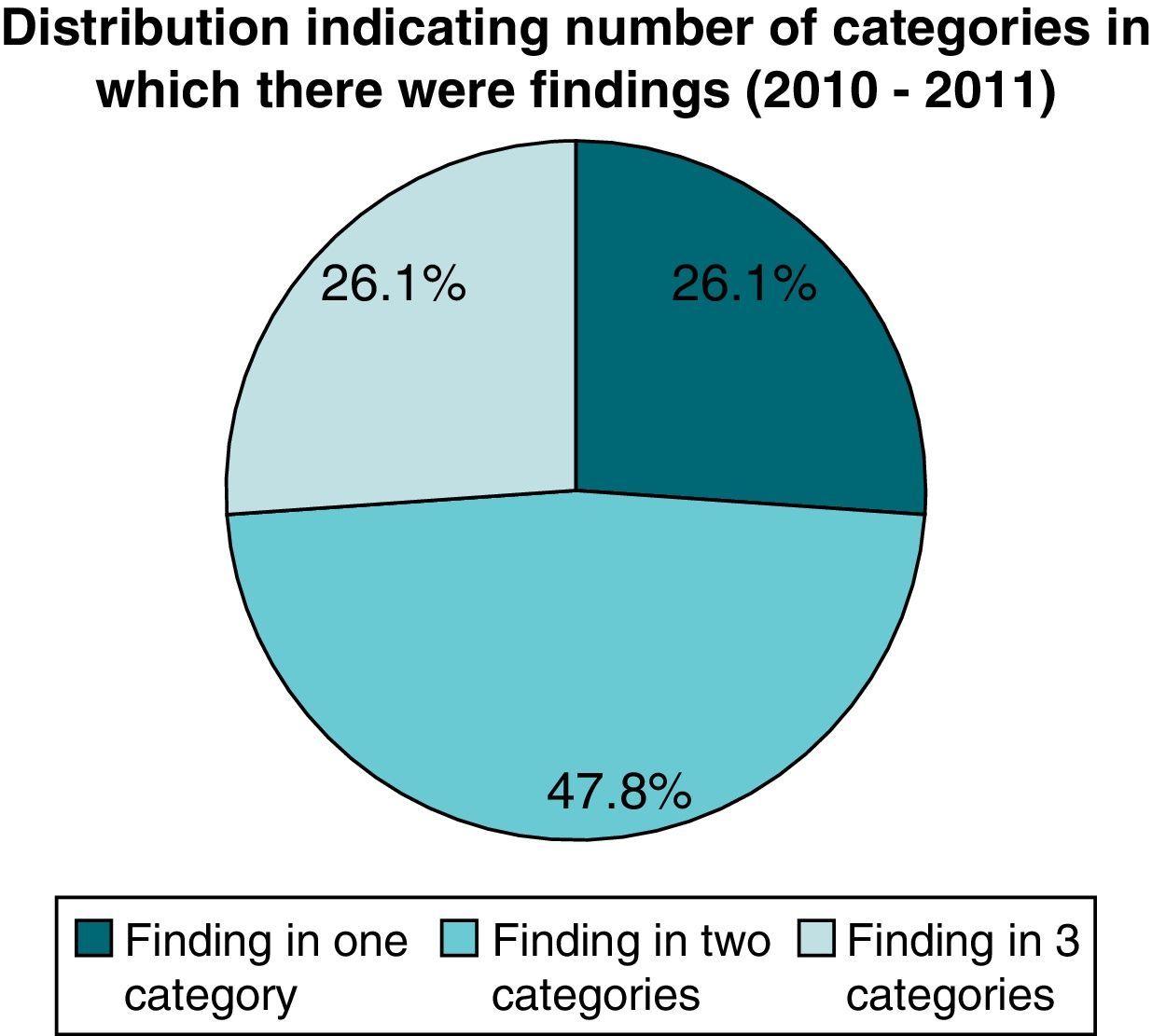

Graphs with respect to all departments in sample (with or without findings on performance information) (Fig. 2).

A statistically significant number of departments (74%) have negative findings on their reporting of performance for both years for both financial years. The percentage of departments that had findings on their audit reports remained constant over the two financial years. It is however important to note that it were not the same departments with findings over the two-year analysis. From 2009/10 to 2010/11, four departments have improved from having findings on their reports to having clean reports while four departments have deteriorated from clean reports to having findings on their performance information on their audit reports.

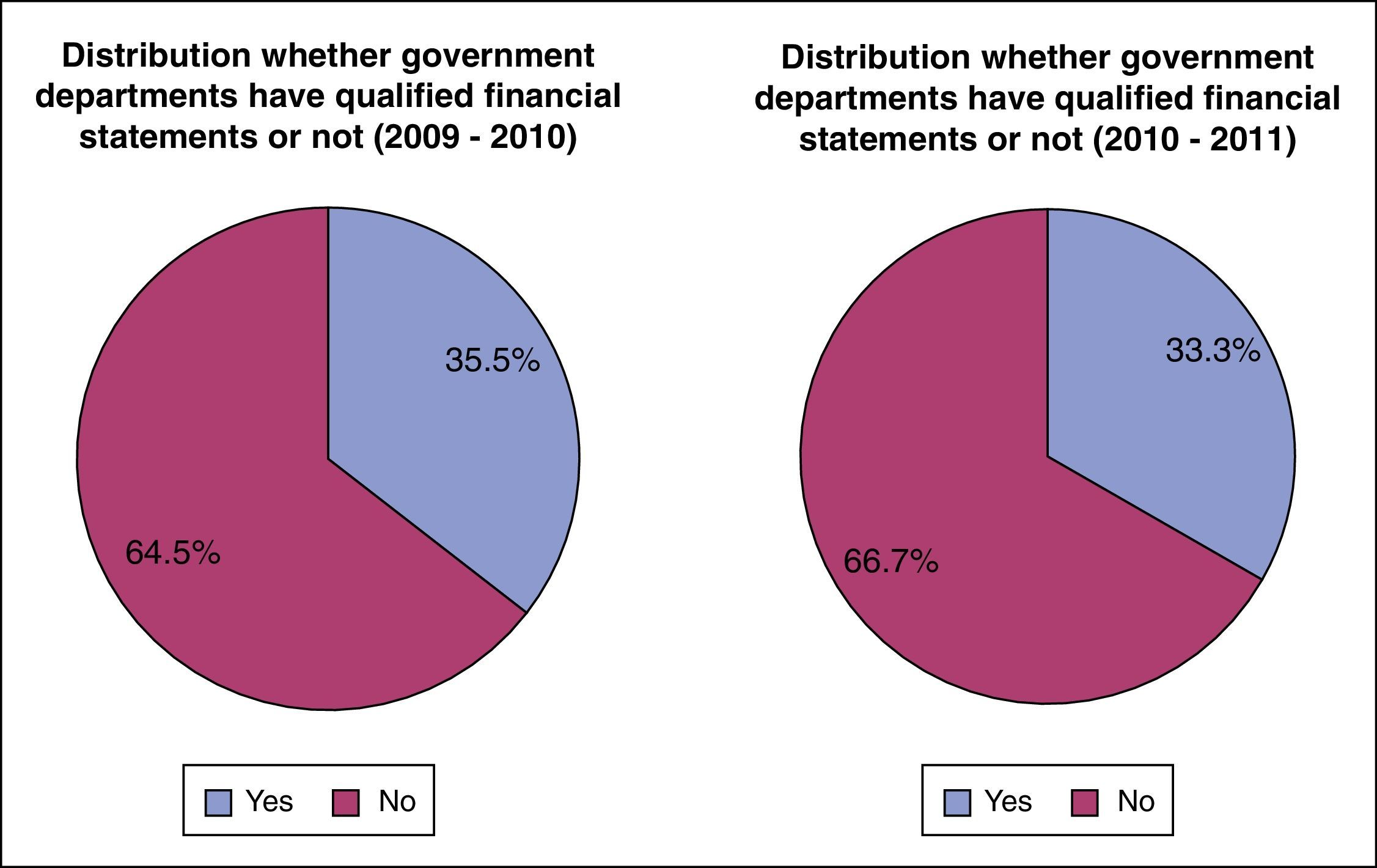

Fig. 3 indicates that the number of departments that have qualified financial statements after the regularity audit have decreased slightly from 35.5% to 33.3% over the two financial years.

Fig. 4 indicates that the percentage of departments that had both financial qualifications and findings on their performance information has decreased from 29% to 25.8%. The percentage of departments with clean audits (without financial qualification or findings on performance information) has remained constant over the two years. As indicated under Fig. 2, it is however not the same departments, some have improved and some deteriorated. There is thus not a general improvement in the quality of the reporting of performance information by national government departments over the two financial years.

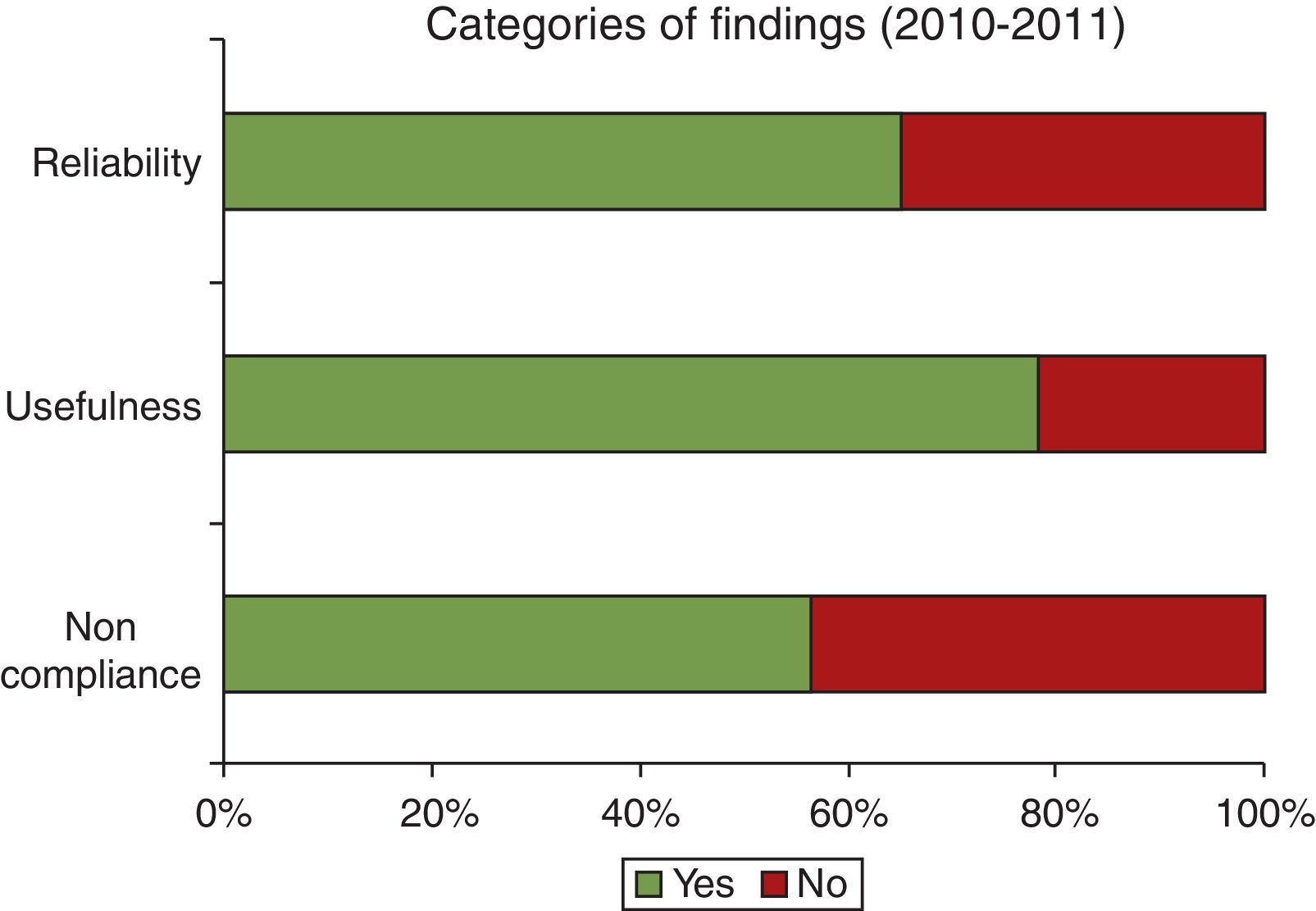

7.2.3Categories of findingsThe findings from the audit of the performance information were categorised into three categories. The Auditor-General commented on the reliability of performance information, the usefulness of performance information and whether the department has complied with the frameworks for the reporting of performance information and the system of control over the generation, collation and reporting of performance information was operating as intended.

There was an increase of findings with respect to the reliability of performance information category (from 29.0% in 2009/2010 to 48.4% in 2010/2011) (Fig. 5). This is an indication of a deterioration of the reliability of the performance information departments reported. 58.1% of the departments in this survey have a finding on the usefulness of information for both 2009/2010 and 2010/2011 financial years. There was no improvement in the usefulness of the performance information departments reported over the two financial years considered. There was an improvement in the compliance with frameworks and systems of control over the two financial years by departments (from 58.1% in 2009/2010 to 41.9% in 2010/2011).

For both 2009/2010 and 2010/2011, there were 19.4% of the departments in this survey that had findings in all the categories and 25.8% of the departments that had no findings on performance information. The number of departments who had findings in one category declined from 2009/2010 (22.6%) to 2010/2011 (19.4%) with 3.2% and the number of departments who had findings in two of the categories increased with 3.2% from 2009/2010 (32.3%) to 2010/2011 (35.5%) (Fig. 6).

The following section provides a further analysis of those departments that did have findings in their audit reports on performance information for each of the two years:

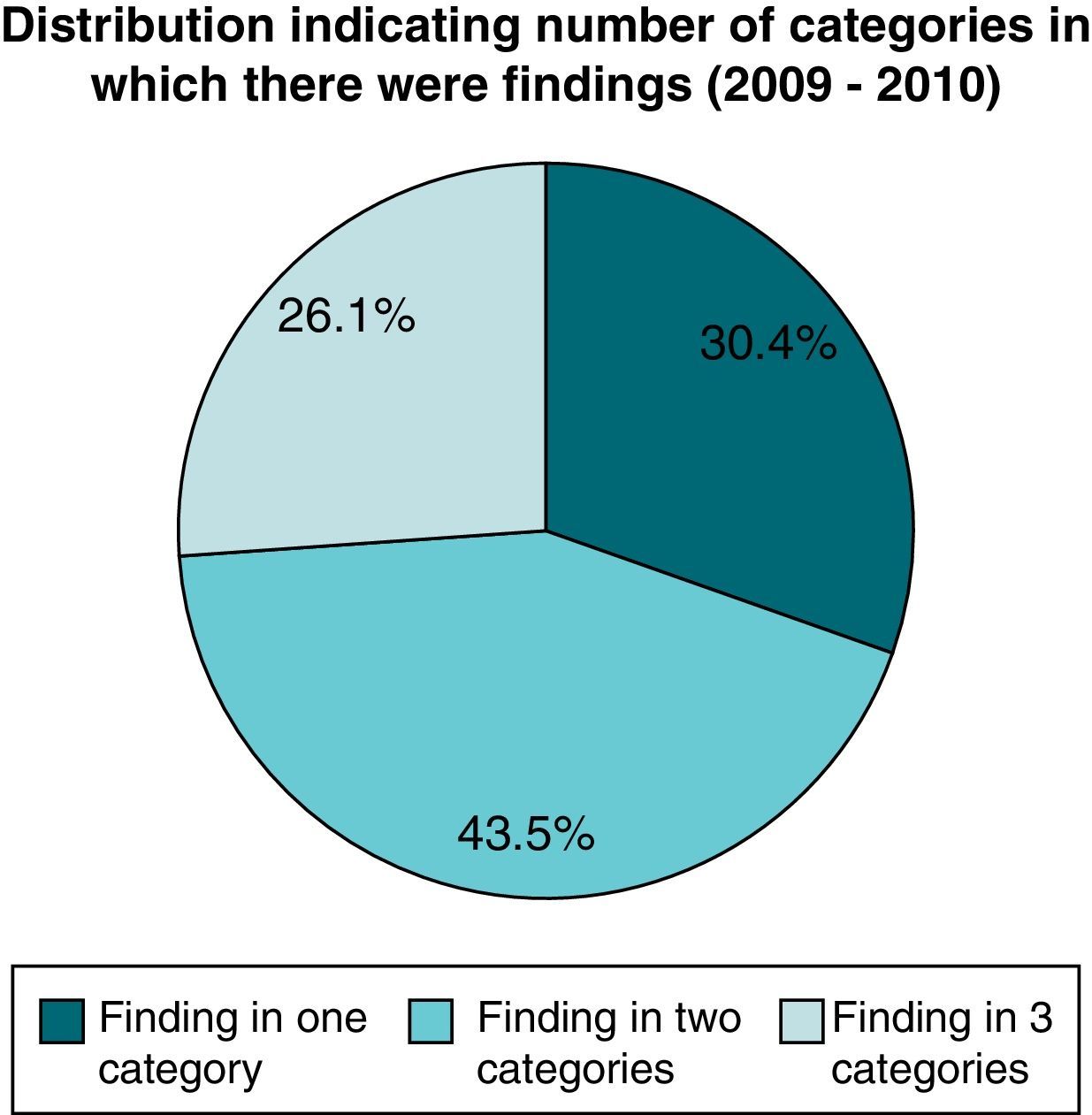

7.2.3.1Graphs with respect to all departments with findings in the sample for 2009/2010 (Figs. 7–9)The following graphs will only include the 74.2% of government departments which had findings in the audit report for 2009/2010.

39.1% of the departments with findings on performance information also had qualified financial statements.

78.3% of the departments with findings on performance information in 2009/10 had findings in the usefulness of information and non-compliance categories. 39.1% of these departments with findings on performance information have findings in the reliability of information category.

In 26.1% of the departments there were findings in all the categories, while in 43.5% of the departments there were findings in two of the categories and in 30.4% of the departments there were findings in one of the categories.

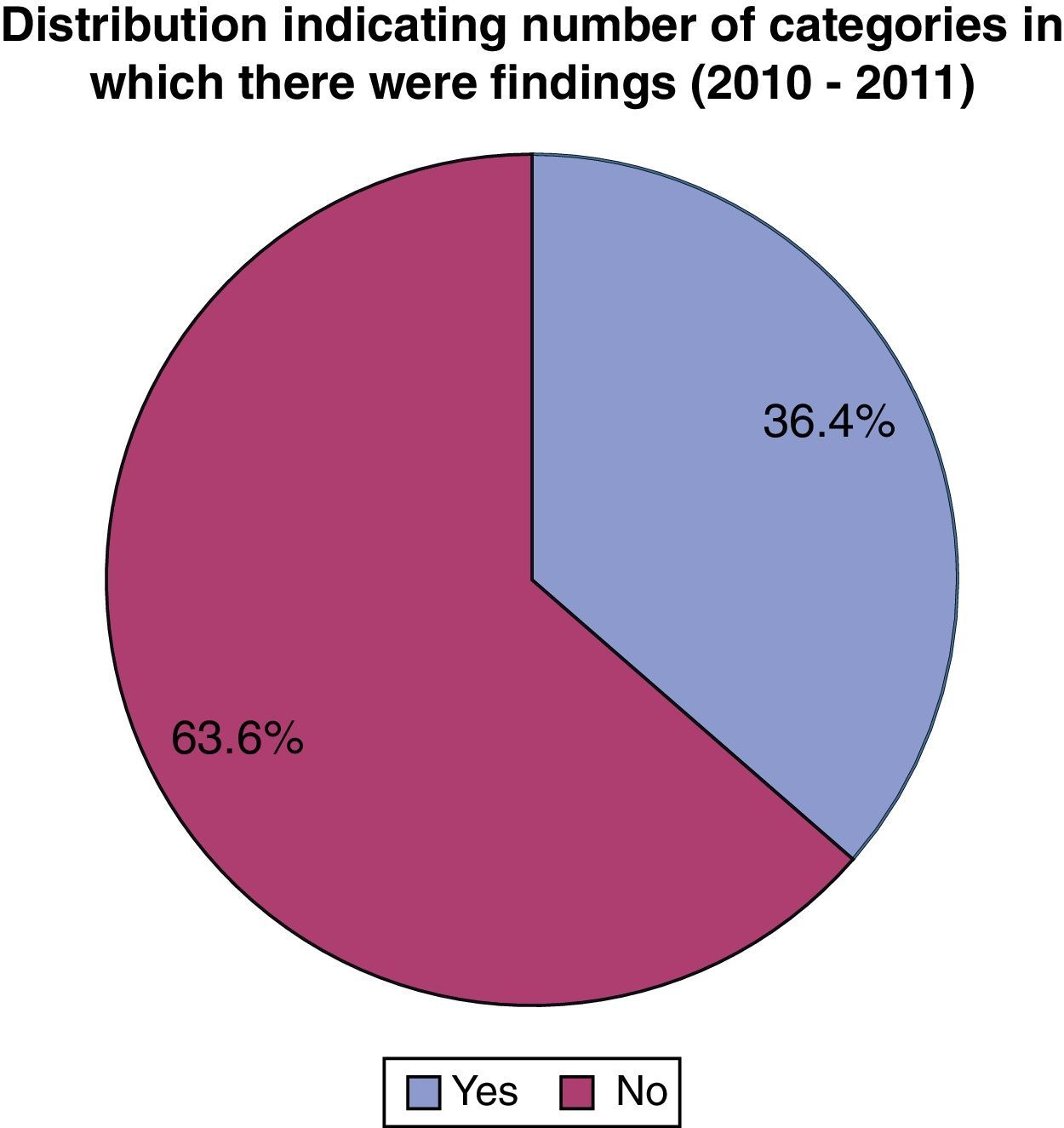

7.2.3.2Graphs with respect to all departments with findings in the sample for 2010/2011Figs. 10–12 will only include the 74.2% of government departments which had findings in the audit report for 2010/20110.

36.4% of the departments with findings on performance information in 2010/11 also had qualified financial statements.

78.3% of the departments with findings on performance information had findings in the usefulness of information, 65.2% of the departments in the reliability of information category and 56.5% have findings in the non-compliance category.

In 26.1% of the departments there were findings in all the categories, while in 47.8% of the departments there were findings in two of the categories and in 26.1% of the departments there were findings in one of the categories.

8Conclusion and recommendationsThe objective of this study was to determine, through qualitative analysis whether the performance information reported in the annual reports of national government departments was reliable and sufficient and to measure the change, either positive or negative over two consecutive financial years. The study commenced with an overview of the legislative and regulatory framework according to which government departments should report their performance against the pre-determined objectives in their strategic and annual performance plans. The Auditor-General has begun an audit of the reported information as part of the regularity audit of departments. Although it is a phased in approach, it will lead to qualified audit opinions in future if departments do not report according to the requirements.

The results of this study clearly indicate that there are still major deficiencies in the reporting of performance information and that there was no material improvement from the 2009/10 to the 2010/11 financial years. In both financial years 74% of departments had findings in their audit reports on their reporting of performance information, some departments have improved, but the quality of the performance information reported by other departments has deteriorated. In general, the majority of departments did not comply with the required regulations and frameworks in both financial years. There was a clear deterioration in the reliability of the reported performance information over two financial years. The usefulness of the performance information has also not improved. There was, however improved compliance with policies and frameworks. There were a number of causes for the shortcomings in the performance information reported. The first being that there was not a sound system of internal control over the generation, collection, and reporting of performance information, or it was not operating as intended. Most departments lacked dedicated human resource capacity to perform the required functions. Further, shortcomings were identified in the strategic plans or annual performance plans of departments where targets were not SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Reliable and Time-bound). The challenge was that strategic plans were completed for a specific medium-term expenditure framework and approved by Parliament. Where deficiencies were identified in the targets and indicators in the strategic plan, it was difficult to change the document. The solution is to change the targets in the annual performance plan. The cause identified for the lack of reliability of performance information was a lack of documented evidence supporting and verifying the information reported in the annual report. There were also shortcomings in the method of reporting of performance information.

Departments should implement or improve their control systems over the generation, collection, verification and reporting of their performance information. There should be a clear understanding in departments of the difference between auditing of the performance of a department/branch/unit and the audit of the information they provide on their performance (as part of regularity audit). In going forward departments should complete strategic and annual performance plans with performance indicators that are SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Reliable and Time-bound).

No information should be included in an annual report without it being supported by documentation and that it is verified. Internal audit units in government departments should provide assurance to management on the quality of the system of control over performance information in the department. Internal audit should audit the quarterly performance information report before it is submitted to the Minister. Internal audit should verify that the supporting documentation for the actual performance reported is available and reliable.

Performance information should be a standing item on audit committee agendas. The audit committee should monitor the system in a department and the assurance internal audit provides on the quality and reliability of performance information. Audit committees should monitor progress against improvement plans drawn up to address findings raised by the Auditor-General on performance information on a quarterly basis.

The various portfolio committees of Parliament overseeing the performance of specific departments against their strategic plans should focus on the result of the audit by the Auditor-General on the performance information of the department. This will give them a good indication whether the actual performance of a department equals the reported performance.

It is clear from the study that if the current situation is allowed to continue and the Auditor-General modifies his audit reports based on the regularity audit of performance information a large number of national government departments in South Africa will have modified (qualified) audit opinions in the foreseeable future.