Agamben's Homo Sacer turns centrally upon “bare life”. However, the following subjects are not thematized: natality, gender, sexuality, the relation of the sexes, the heterosexual character of the symbolic order and political culture, the interest of women in the reproduction of life. The entire question of sexual difference —like that of the difference between victim and perpetrator, between witnesses and those born afterwards— is banned from Agamben's horizon. Thus a deep unease remains, which this paper is intended to explore. It will first present the methodological and theoretical inspirations that Homo Sacer owes to the thought of Carl Schmitt. Secondly it will show that Schmitt's concepts of nomos and the state of exception cannot provide a suitable basis for rewriting Foucault's concept of biopolitics.

Homo Sacer de Agamben se centra en la “nuda vida”. Sin embargo, no tematiza la natalidad, el género, la sexualidad, la relación entre los sexos, el carácter heterosexual del orden simbólico y la cultura política, el interés de la mujer en la reproducción de la vida. La cuestión de la diferencia sexual —como la diferencia entre víctima y perpetrador, entre testigos y los nacidos posteriormente— es excluida desde el horizonte de Agamben. A partir de una profunda incomodidad que despierta Homo Sacer, este artículo se propone explorar las inspiraciones metodológicas y teóricas que este libro de Agamben debe al pensamiento de Carl Schmitt. Después, mostrará que los conceptos de Schmitt de nomos y estado de excepción no pueden proveer una base adecuada para reescribir el concepto foucaultiano de la biopolítica.

Once again there appears to be a need for philosophy in the strong sense of the word. This, at least, is suggested by the international acclaim of the theses of Giorgio Agamben. In his three-volume Homo Sacer, the first volume of which was published in 1995, the Italian philosopher presents a new attempt at a critique of violence as a fundamental critique of Western thought (cf. Agamben 1995). The book subtitled Sovereign Power and Bare Life had its first extraordinary impact, however, when it appeared in English translation in Stanford University Press's lauded series Meridian:Crossing Aesthetics (cf. Agamben 1995).

The legitimacy of Agamben's allusion to the scandalous conditions under which human beings are today interned in camps, confined or deported without legal rights, is confirmed by the conditions in Guantánamo Bay (cf. Assheuer) as well as by the political movement of the sans papiers. In an ever-increasing number of locations in the world, “legal grey zones” are created in which human beings are treated as superfluous bodies. Despite all the evidence for Agamben's thesis, a deep unease remains. I would like to explore this unease in what follows. A discussion of the foundations of Homo Sacer seems appropriate not only because of the book's uncommon impact but also because Agamben's philosophy of biopolitics takes on some highly topical and important questions. The demand for a certain precision becomes all the more pressing precisely because of the topicality of the themes treated. Thus, for example, Agamben takes it upon himself not only to further Foucault's concept of biopolitics but also to correct it in crucial places. Yet does Agamben's existential philosophy actually represent a correction of Foucault? Doesn’t it lead, rather than to a differentiation, to a de-historicization and trivialization of the concept of biopolitics? I would like to return to these questions at the end of my paper. I will begin by investigating the reasons for my aforementioned unease, which will lead us to consider Agamben's reception of the German lawyer Carl Schmitt's contentious theses of legal theory. The presentation of the methodological and theoretical inspirations which Homo Sacer owes to the thought of Carl Schmitt will lead us finally to the question of whether the concepts of nomos and the state of exception, which belong to political ordering, are actually suitable to rewrite Foucault's concept of biopolitics.

Thought in the State of ExceptionThe first reason for my unease lies in Agamben's conception of philosophy as thought in the state of exception.

Agamben is fascinated by a form of philosophical thought which has the power to determine questions of existence, a fascination he transmits to his readers. As an avowed pupil of Martin Heidegger and Hannah Arendt (cf. Leitgeb and Vismann: 16-21), he combines the fundamental ontology and analysis of totalitarianism in which Hannah Arendt interprets the concentration camps as “the laboratories in the experiment of total domination” (Agamben 1998: 120) with Carl Schmitt's decisionism. From this position, he formulates the need for a re-reading and correction of the Foucauldian concepts of sovereignty and biopower. Following Carl Schmitt, he holds the opinion that the truth is revealed solely in the extreme, in the state of exception.

He elaborates what he wishes to be understood within a philosophy of the state of exception in the third part of Homo Sacer, Remnants of Auschwitz. Here he elaborates the most extreme limit of thought from an interpretation of the figure of the “muselmann.” Those prisoners in the Nazi death camps who moved on the border between life and death, wholly disempowered, were named “muselmänner.” Agamben starts with the concept of the “muselmann”, frees it from its historical situation, transforms it into a metaphor, makes it the cornerstone of his concept of philosophy, and finally builds his philosophy upon it. The “muselmann”, he writes, is “the perfect cipher of the camp” (Agamben 1999: 48). The “muselmann” represents, he explains further, “the nonplace in which all disciplinary barriers are destroyed and all embankments flooded.” With this, Agamben marks not only the boundary of that which can be said, but marks at the same time, in the ethical and epistemological sense, a border crossing claim which he pursues with his understanding of philosophy. Following upon the above analysis of the “muselmann”, he defines his concept of philosophy: “In this sense, philosophy can be defined as the world seen from an extreme situation that has become the rule (according to some philosophers, the name of this extreme situation is ‘God’)” (Agamben 1999: 50). Agambenian philosophy thus promises a worldview from the perspective of the extreme situation, which, as he adds, some philosophers designate as “God”. One can understand this as philosophy in the strong sense of the word.

From the perspective of critical philosophy, it appears, of course, doubtful whether an examination of the world from a divine perspective would contribute anything essential to a better understanding of the world. These doubts are aimed at the philosophical foundations on which a critique of violence might be sustained. The theoretical invocation of the extreme situation encourages identification with a violence invoked in the first place in the construction of the state of exception. Agamben succumbs to this temptation when he declares that the “muselmann” is the “perfect cipher” for the state of exception and then philosophically seizes upon this most extreme border situation in order to regard the world from its perspective. Philosophy in this sense dissolves differences instead of doing them justice. It becomes violent in itself.

Agamben claims for himself the position of a philosophical outsider. He is, in fact, one of few philosophers not to approach questions concerning the border between life and death posed by the rapid development of the life sciences from the perspective of analytic ethics. Instead of analyzing meanings, he develops broad philosophical foundations which have put pressure on decisions about death and life, on new definitions of the beginnings of life, the different types of being dead, and what constitutes a life worth living. What matters for Agamben is the investigation of a culture that, according to his thesis, finds its inner cohesion through the creation of zones of indifference between life and death. He finds these zones on the one hand in medicine, which artificially prolongs life, and on the other hand in a politics that robs people of their fundamental (human) rights in order to confine them in camps, and there to reduce them to their bodies, their bare existence. According to Agamben, the democratic judicial order proves itself a facade for a logic that reveals its violence in the establishment of interstitial zones outside the law, in which people are compelled to represent “bare life”. He calls this culture modernity and locates its paradigm or matrix in the “camp” (Agamben 1998: 166). His thesis culminates in the claim that the camp forms the nomos of modernity.

The Legacy of Carl SchmittHomo Sacer would have been inconceivable without Carl Schmitt's theory of sovereignty. It is Agamben's point of departure, and he invariably returns to it. Schmitt not only represents the godfather of a philosophical procedure oriented around the state of exception, but, with his theory of sovereignty, supplies Agamben with the theoretical foundation for his history of the West.

Now the concepts, so selectively and obviously derived from Carl Schmitt, are polemical concepts, as Jacob Taubes, the influential scholar of religious studies, has aptly emphasized. These are fighting words. They draw their obviousness from the fact that they constitute themselves as oppositional concepts; that is: the concepts of Carl Schmitt derive their power of persuasion from the fact that they are aimed at a visible, although also sometimes invisible, enemy. This is precisely what creates their polarizing character and their apparent clarity. They release one from doubt and insecurity; they reduce all complexity and ambiguity.

Similarly, in Homo Sacer, Agamben creates the appearance of clarity by adopting Schmitt's overly-simplifying procedure and appropriating Schmitt's simplistic concepts as his own foundational ones. In this appropriation, however, Agamben ignores the fact that Schmitt developed his theory of sovereignty as an opposing standpoint to the “rule of law”, and ignores the fact that Schmitt equates the “rule of law” with legal positivism and the latter with “Jewish liberalism”. This approach is closely connected with the anti-Semitism constitutive of Schmitt's thought (cf. Gross). Agamben does not problematize this anti-Semitism, fundamental to Schmitt's theory of the nomos as well as his friend/enemy schema. Instead, he extends the currency of the concept of the nomos by ontologizing it.

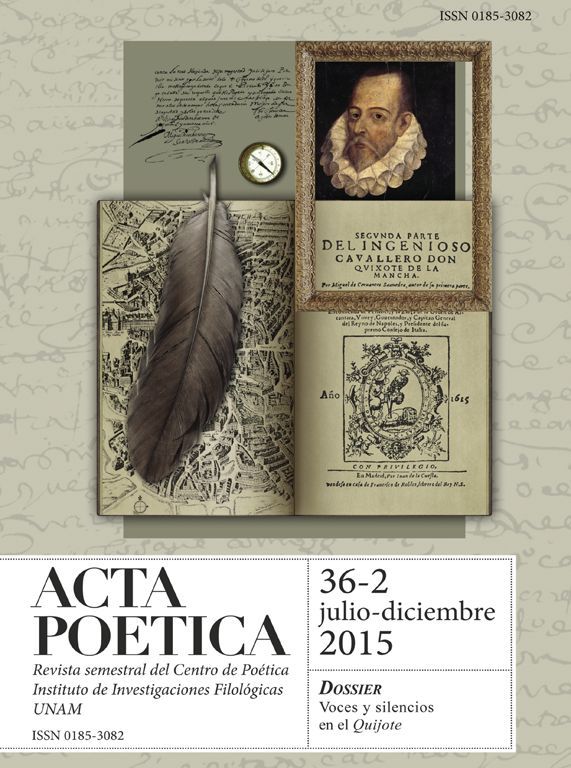

I would like to expand upon these critical reflections concerning Agamben's ties to Schmitt in the course of a description of Agamben's theses. This will lead us to the question of whether Agamben's re-connection of biopolitics and sovereign authority in fact represents a correction to Foucault's confusion of biopolitics and sovereign authority. I cannot, here, go into the meanings which Hannah Arendt's analyses of totalitarianism put forward, nor can I treat Agamben's relation to Walter Benjamin, from whose essay, “Critique of Violence”, Agamben borrows the concept of “bare”1 life. I would like, however, to point to Samuel Weber's critical examination in his essay “Gestus und Gewalt Agamben über Benjamin über Kafka über Cervantes – Kettenlektüre” [“Gesture and Violence: Agamben on Benjamin on Kafka on Cervantes– Chain-reading”]. Samuel Weber delivered the text as a lecture on February 20, 2004 at the University of Basel.

The Nomos and German LawAgamben's philosophical treatment of the political begins with the existence of an “original political relation” (Agamben 1998: 181). This forms the foundation of the twenty-five-hundred-year history of the West described by the author. Agamben equates this original political relation with the “ban”, understanding by “ban” the state of exception as a zone of indistinction between inside and outside, between inclusion and exclusion (181). The ban is an act, and presupposes an actor who delivers the ban: this actor is the sovereign who with the decisive act —that is, the ban— posits law, and with this positing of law abolishes the indistinction of outside and inside. With the ban, the sovereign creates an outside and an inside, and thereby constitutes the sphere of the political. Now, with the construction of the political, as Agamben remarks and upon which he founds his theory of violence, the sphere of indistinction is not only abolished but created in the same stroke, in so far as the sovereign constitutes the legal order. The positing of law is accompanied by the production of a sphere that lies outside the space of the law. Agamben terms this sphere “bare life”. As the zone of indistinction banned to the outside of the inside, bare life marks the “threshold of articulation between nature and culture” (181). Agamben equates this articulation with the articulation of zoe, in the sense of (natural) bare life, and bios as a cultural or political form of life.

Agamben explicitly distances himself from all theories that found sovereignty upon an antecedent contract. He relies exclusively upon Carl Schmitt's theory of sovereignty. Contractual theories lack, according to Agamben, the very metaphysical core inherent in the positing of the law.

Agamben thereby universalizes —nolens volens— that exclusive concept of law which Schmitt devised as the essence of German law in the thirties, and which he extended to all of Europe's peoples in 1950 as the “nomos of the earth”: the nomos. The nomos, too, is originally a polemical concept. Schmitt devised it in opposition to the concept of the “law”. The “law” embodies for Schmitt the epitome of the norm and thus of the “should”. For Schmitt, the norm was the expression of the very legal positivism he was attacking, and was consigned to the vocabulary of the “enemy”. In Schmitt's cosmos, “Jewish liberalism” represented the incarnation of the enemy and was linked to the concept of the law. He accused liberalism of conceiving of the law as “universal”, “abstract”, and hence detached from the “concrete” ground, people, state, and life. In his book, Carl Schmitt und die Juden [Carl Schmitt and the Jews], Raphael Gross traces in detail the history of the origin of the concept of the nomos. The concept of nomos as the expression of “German law” was, for Schmitt in the thirties, the synonym for the relatedness of the German ground, people, and leader. The law, denounced as “abstract”, “Jewish”, and “groundless”, did not fit into Schmitt's theory of sovereignty, oriented around the state of exception and the decision, and was therefore passionately opposed by him. The association of law and justice is linked to the claim of universality. Schmitt could only see in this the origin of a disorder threatening the authority and unity of the State. The law was, for him, the beginning of anarchy.

Schmitt's theory of sovereignty puts the category of ordering [Ordnung] in place of the question of justice.

Now, Agamben constructs his theory of the ban as the “original political relation” precisely upon the dual meanings of ordering [Ordnung] and localization [Ortung] elaborated by Schmitt in The Nomos of the Earth. He adopts without commentary the imbrication of the legal and spatial ordering established by Schmitt —and without a word employs the alienating and highly strange, but extremely significant, sexual metaphor in Schmitt's remarks on the “taking of land”—. As in all of Homo Sacer, which turns centrally upon “bare life”, neither natality nor gender [Geschlechtlichkeit], neither sexuality nor the relation of the sexes, neither the heterosexual character of the symbolic order and political culture nor the interest of women in the reproduction of life, is thematized. The entire sphere of the question of sexual difference —like that of a possible relation between law and justice— is banned from Agamben's horizon.

Agamben thus assumes, without commentary, the program of an understanding of law which has as its origin a “Volk or people's theology of the nomos”. Furthermore, Agamben not only advances Schmitt's conception of nomos as the original taking of land [Landnahme] as the “primeval division and distribution” [Ur-Teilung and Ur-Verteilung] (Schmitt: 67) but also declares it to be the archetypal form of the positing of law and of the constitution of the political in general.2 He then supplements Schmitt's interpretation of the nomos as the sovereign “taking of land” [Landnahme] with the thesis that the sovereign nomos is not only the taking of land, but is first and foremost a “taking of the outside” and thus an exception [Ausnahme] (Agamben 1998: 19). With this he goes further than Schmitt, who at least recognizes the thought of a law without space as the stance of the enemy. Agamben identifies law with justice and justice with the nomos, and thereby robs himself of all possibility of thinking justice in an alternative form than the nomos, for instance as universal law.3

History of DeclineAgamben follows Carl Schmitt in his definition of the sovereign act; as already indicated, however, he adds to the combination of appropriation, distribution, and production —wherein Schmitt saw the function of the nomos as mediating between the state, the judiciary and the economy— the creation of a state of exception, which would take place simultaneously to the establishment of the legal order. This allows Agamben to shift Schmitt's focus from the State to the camp. For the exception materializes in spaces that stand outside the law, as he points out in his interpretation of the ban as the original act of the sovereign. On the other hand, these spaces assume different forms in the course of Western history. They change in parallel to the relation in which “bare life” stands to the sovereign or the exceptional case stands to the rule.

Now, according to Agamben, it is decisive for modernity that, together with the process by which the exception everywhere becomes the rule, the realm of bare life —which is originally situated at the margins of the political order— gradually begins to coincide with the political realm, and exclusion and inclusion, outside and inside, bios and zoe, right and fact, enter into a zone of irreducible indistinction (9).

The conclusion is that sovereignty —whose original function of decision consists in the discrimination between “bare life” and the political, zoe and bios, or more simply, nature and culture— switches from the State to the camp. Agamben interprets the camp as the territorialization of the exception. This explains the claim that the camp is the nomos of modernity. It is, of course, assumed that one shares Agamben's diagnosis according to which the exception increasingly becomes the rule; only then is one in a position to grasp the whole scope of Agamben's apocalyptic vision. Behind the evocation of a “biopolitical catastrophe” hides the same anxiety which drove Schmitt to defend the state of order —the fear of the intermingling of nature and culture, death and life, the fear of anarchy and chaos.

The elevation of the camp to the matrix of modernity rests upon the thin basis of Carl Schmitt's interpretation of justice as nomos and the claimed nexus of justice, order and territory.

The additional interpretation of the sovereign act as the original political relation of the ban, opens up a narrow range of combinatory possibilities out of which Agamben delineates the history of the West. This history follows the logic of violence inscribed in the ban and is correspondingly a history of decline.4

In modernity, the “taking-of-land” in the “exception” [Ausnahme], quite literally, is materialized in the establishment of camps. With this, Agamben also claims, the exception becomes the rule. The modern is characterized by the unmediated elevation of political space above that of bare life. I quote from Homo Sacer: One of the theses of the present inquiry is that in our age, the state of exception comes more and more to the foreground as the fundamental political structure and ultimately begins to become the rule. When our age tried to grant the un-localizable a permanent and visible localization, the result was the concentration camp. The camp —and not the prison— is the space that corresponds to this originary structure of the nomos (20).

In this perpetual state of exception, we are all, according to Agamben, virtual “homines sacri” (115), all potential Jewesses and Jews, whom the author designates as “the representatives par excellence and almost the living symbol of the people and of the bare life that modernity necessarily creates within itself, but whose presence it can no longer tolerate in any way” (179).

Once again, this passage clearly shows how the thinking of the state of exception functions and where it leads. The orientation around the extreme promises the highest concreteness but leads to empty abstraction, as the sweeping generalization that we are all potentially homines sacri makes clear. As such, it is not only an affront to the concrete sufferings of the victims and their relatives. It does not only level out the differences between victims and perpetrators, between witnesses and those born afterwards. It also effaces existing and —through the implementation of globalization— increasing class differences between rich and poor, north and south, between those who fulfill and those who deviate from the norm.

It is as if Agamben were playing into Foucault's hands, for Foucault criticises the concentration on the theory of sovereignty precisely on the grounds that through an ideology of a fictive unity of power, it renders invisible actual relations of domination and difference, as well as the perpetual struggles for power.

Both the category of the state of exception as well as the concentration on the camp as the “taking of land of the exception” refer back to the origin of Agamben's theory in Carl Schmitt's doctrine of sovereignty and his concept of the nomos. Finally, he is Schmittian in his interpretation of the collapse of inner and outer as the irruption of a catastrophe, a catastrophe Schmitt compares to the coming of the Antichrist. Thus, according to Agamben, the catastrophe of modernity is the consequence of the dissolution of the distinction between political existence (bios) and bare life (zoe), in so far as bare life, rather than being differentiated from the political, becomes the foundation of the political in the camp.

While, for Schmitt, the distinction between friend and enemy represents a necessary category for the construction of the political, Agamben replaces these categories —in explicit analogy to Schmitt— with the distinction between “bare life” and “political existence” (8). Of course, Agamben aims to expose the violence characteristic of, and essential to, the Western politico-juridical model of power from its beginnings. He traps himself, however, in a circle of violence, culminating in the story of decline presented here, by ontologizing and thereby dehistoricizing it.

The Critique of Michel FoucaultBy focussing on Schmitt's theory of sovereignty, Agamben claims to re-introduce questions of legal theory into the discussion of biopolitics. Precisely this legal theoretical aspect is supposedly neglected by Foucault in his concentration on a dynamical model of power. Does, however, Agamben's reconnection of biopolitics to sovereign authority in fact represent a correction to Foucault's limitation of sovereignty and biopower? I would like to close by pursuing this question.

Agamben first reproaches Foucault for having failed to find a link between his investigations of the “techniques of the self” and the political strategies of biopower (5f). Then he reproaches him for neglecting to provide an analysis of modern totalitarianism and the concentration camp (119). Agamben seeks to address both points with his reformulation of biopolitics.

However, he reduces the complex and far-reaching first question of how the intermingling of the techniques of the self may be thought along with the processes of the totalization of power, to the sole aspect controlling his own epistemological interest: how the biopolitical model of power interferes with the juridico-institutional model of power. Thus power is no longer thought of as a complex relation of forces, as in Foucault, but appears as the formation of two blocks. This has as a consequence, first, that the whole complex of struggles, and with it the question of oppositional movements, remains unthought. Second, Agamben omits precisely the interest in epistemology which had guided Foucault in his research on the techniques of the self: the question of how, in view of the disciplining and subjugation of the subject, to explain the development of an art of critique.

His answer to the question of how the biopolitical model of power interferes with the juridico-institutional one is simple: there is no difference between sovereign authority and biopower, for the biopolitical body is nothing other than the production and therefore the original activity of sovereign power itself. Thus he arrives at the statement that biopolitics has always been an integral aspect of sovereign authority and therefore just as ancient as the sovereign state of exception itself. The modern state consequently represents nothing new, but in making biological life the center of its calculations, it merely brings to light the secret tie that always already binds power to bare life (6). Thus, the modern state is tied to the immemorial of the “arcana imperii” according to Agamben's law of a “tenacious correspondence between the modern and the archaic, which one encounters in the most diverse spheres” (6).

In fact, Agamben's reformulation of the concepts of sovereign authority and biopolitics results not only in a monolithic, static model of power but also in a similar move that blocks any view of the historically efficacious forces of resistance. By bowing down before the sovereign authority to which he attributes, as the “supreme power”, the “capacity to constitute oneself and others as life that may be killed but not sacrificed” (101), Agamben reinstalls the ominously remaining sovereign as the solitary actor and motor of history.

Unlike Agamben, Foucault conceives of power as a relation of forces and thinks of it from the bottom up. For Foucault, it is a matter of encouraging the sort of knowledge he calls buried or subjugated (2003a: 8). Accordingly, he grants the highest importance to the requirement not to read into history what one already knew beforehand. The buried historical knowledge he sought to unearth concerned the historical knowledge of struggles, precisely the knowledge a monolithic model of power relegates to the darkness of forgetting. It obstructs a view of the actual and possible historical forms of resistance.

Starting with the Enlightenment conceived of as a relation of forces, Foucault develops in his late work the possibility of an ethics in the form of an “aesthetic of existence”. He links this with the answer he gave in a 1977 lecture to the self-posed question “what is critique?” Critique is, as he formulated it in 1977, an attitude and, as such, a virtue; according to the now famous general characterization, critique is: “the art of not being governed” (2003a: 265). Foucault locates the “core” of this art of critique, which he equates with the art of self-legislation, in three places:

First, the Bible: emerging out of the question of how to interpret the Holy Text, and whether in general the Bible corresponds to the truth.

Second, the juridical: arising from the impulse to no longer accept existing laws because one senses that they are unjust.

Third, the epistemological: the development of the sciences led to the renunciation of obedience to an authority that determined what was true and what was untrue.

From this tripartite origin of critique, Foucault describes the “core of critique” as the “the bundle of relationships that are tied to one another, or one to the two others, power, truth and the subject”. Critique therefore questions the “truth on its effects of power and questions power on its discourses of truth” and now allows itself to be specified as “the art of voluntary insubordination, that of reflected intractability” (266). It is no accident that Foucault approaches the question of resistance via the language of law. The art of “self-legislation” is another word for autonomy —giving law to oneself—. Now, for Foucault, the investigation of the techniques of the self is connected to the question of the conditions that would give the most space to the art of critique. Techniques of the self are therefore not only techniques of subjugation but mean every form of creating a relation of the self to itself. Also belonging to this is the form that Foucault, in one of his last lectures from 1983-1984, calls the parrhesiastic relationship of the subject with himself (Foucault 2001: 13). Parrhesia may be translated as “speaking freely” but also as “speaking truly”. It designates a relation of the subject that speaks with itself. And it does this in such a way that the subject binds itself both to the enunciation and to the enunciating itself. In this “parrhesiastic enunciation”, Foucault discovers a technique of the self which can be regarded as the condition of possibility of critique. Through the double relation contained in the parrhesiastic utterance, the subject enters into a binding relation with himself and, as such, practices the art of critique: In parrhesia the speaker emphasizes the fact that he is both the subject of the enunciation and the subject of the enunciandum – that he himself is the subject of the opinion to which he refers. The specific ‘speech activity’, of the parrhesiastic enunciation thus takes the form: ‘I am the one who thinks this and that’ … the commitment involved in parrhesia is linked …to the fact that the parrhesiastes says something which is dangerous to himself and thus involves a risk (13).

Through this double relationship, the subject enters into a binding relation to that which he has enunciated as truth. This relation enables him to be released from the authority of the accepted form of justice and to contradict an authority felt to be untrue and thus unjust. The parrhesiastic utterance, which Foucault explicitly distinguishes from the performative utterance, is taken as a point of departure for the art of self-legislation. The risks indicated, which the subject takes upon himself, extend to the penalty of death. In the passage cited, Foucault introduces as an example, the subject who “rises up against the tyrant and speaks the truth under the eyes of the whole courtly state”. Hannah Arendt poses the question underlying Foucault's investigations concerning the techniques of the self, though in another terminology, in her essay Personal Responsibility under Dictatorship (cf. Arendt). In this essay, Arendt refers to the question of the (absent) resistance to National Socialism. Arendt objects that one should not question why so many cooperated but rather why some did not cooperate, thereby incurring the risk of all sorts of consequences.

The discovery and determination of these traces of an “art of not being governed” presupposes a form of thought which neither understands history as mono-causal nor power as monolithic. It is a form of thought that understands itself rather as an historical, philosophical praxis and as such “a practice of the self”, and in this sense as a “technique of the self” (Foucault 1985: 13).

State RacismHow, then, does Foucault describe the relation of biopower and sovereign authority, and which consequences does he draw for a possible explanation of National Socialism? In contrast to Agamben, Foucault understands biopower decisively as an historical phenomenon. Its emergence is tied to the development of the modern sciences. If one divorces the concept of biopolitics or biopower from the development of statistics, modern medicine, biology, evolutionary theory, and the interpenetration of the apparatuses of knowledge with the institutions of the state, it then becomes an empty concept. As opposed to Agamben, who seeks to ground politics philosophically, Foucault conceives of politics as the relationship between power, truth, and the subject. Thus he does not understand truth as a transhistorical phenomenon but as the effect of concrete historical techniques linked to the history of the sciences. Unlike Agamben, Foucault does not reason from philosophy but from epistemology. From this perspective, one of Agamben's central claims appears to be pure speculation. That is the claim that the modern state is nothing new, but the fact that it places biopolitical life at the center of its calculations only reveals the secret bind which has always already linked power and “bare life”.

For “life itself”, just as much as biopower, does not exist before the politics of the population. Biopolitics is based on the “societal body” developed in the 19th century, which is itself an effect of the apparatus of knowledge that developed alongside the modern sciences. Thus, as early as The Order of Things, which appeared in 1966, Foucault emphasizes that the concept of life in itself, or bare life, is the product of a science which has only existed for the past 150 years: Historians want to write histories of biology in the eighteenth century; but they do not realize that biology did not exist then (…). And that, if biology was unknown, there was a very simple reason for it: that life itself did not exist. All that existed was living beings, which were viewed through a grid of knowledge constituted by natural history (Foucault 1973: 129f).

In his analysis of totalitarianism presented at the close of his lectures at the Collège de France in 1975/6,5 Foucault starts from the question of how it is possible that a political authority can exercise the function of death if it is true that disciplinary and regulatory bio-power always seeks more power for itself. In other words, how is it to be explained that under the dominance of a biopower whose function consists in the optimization of life, not only millions of people but whole peoples were murdered?

The link between sovereign authority and biopower is, as Foucault convincingly shows, not the sovereign but state racism. “In a normalizing society, race or racism is the precondition that makes killing acceptable” (Foucault 2003b: 256).

Out of this results the analysis of totalitarianism: first, that it is only explicable under the condition that biopower and the power of sovereignty are understood as distinctive forms of power. That, second, biopower is conceived of as a recent historical form of power linked to the development of the modern scientific apparatus. That, third, this power has as its aim the optimization of life, where life is related in this context to the “social body” or race. And that, fourth, the power of sovereignty did not abdicate, but rather, in the course of these modifications, changed itself by bringing forth state racism in order to continue to exercise its function. Thus, totalitarianism can only be understood with recourse to racism.

Summarizing, Foucault describes the National Socialist State as follows: The Nazi State makes the field of the life it manages, protects, guarantees, and cultivates in biological terms absolutely coextensive with the sovereign right to kill anyone, meaning not only other people, but also its own people. There was, in Nazism, a coincidence between a generalized biopower and a dictatorship that was at once absolute and retransmitted throughout the entire social body by this fantastic extension of the right to kill and of exposure to death. We have an absolutely racist State, an absolutely murderous State, and an absolutely suicidal State. A racist State, a murderous State, and a suicidal State. The three were necessarily superimposed, and the result was of course both the “final solution” (or the attempt to eliminate, by eliminating the Jews, all the other races of which the Jews were both the symbol and the manifestation) of the years 1942-1943, and then Telegram 71, in which, in April 1945, Hitler gave the order to destroy the German people's own living conditions (260).

The self-obligation to differentiate belongs to the task of a critique of violence; for the task of the critique of violence, as Benjamin establishes in the first sentence of his essay, can only be defined as “that of expounding its relation to law and justice”, since a “cause, however effective”, only becomes violent “only when it enters into moral relations” (Benjamin: 236). Agamben's elevation of the camp to the matrix of modernity, his globalizing explanation of the state of exception to the rule, removes itself from history. In this very abstraction, an abstraction that carries with it a further abstraction from “ethical relations”, he carries out the violence which he purports to criticize.

I have translated both “das bloße Leben” and “nacktes Leben” as “bare life throughout, in accordance with the English translation of Homo Sacer [CED].

Cf. Agamben 1995: 19. “What is at issue in the sovereign exception is not so much the control or neutralization of an excess as the creation and definition of the very space in which the juridico-political order can have validity. In this sense, the sovereign exception is the fundamental localization (Ortung), which does not limit itself to distinguishing what is outside and inside, the normal situation and chaos, enter into those complex topological relations that make the validity of the juridical order possible”.

Cf. For different ways of conceiving of the law, see Bär and Deuber-Mankowsky, “Wie viel Glaube ist im Staat? Ein transdisziplinärer Austausch zwischen Kulturund Rechtswissenschaft”: 89-111.

The first possibility consists in the success of the state of indifference which accompanies the exception through the differentiation of inside and outside and private and public (in Hannah Arendt's sense). This is the case in the Greek polis, in which, according to Agamben, a differentiation was made between the domain of the oikos as the domain of zoe, appearing here as “bare life”, and that of the polis as the domain of political life. “In the classical world, however, simple natural life is excluded from the polis in the strict sense, and remains confined —as merely reproductive life— to the sphere of the oikos” (Agamben 1995: 2). Agamben refers to Aristotle's differentiation of the “oikonomos (the head of an estate) and the despotes (the head of the family), both of whom are concerned with the reproduction and the subsistence of life (2) from the politicians, who are concerned with the political. The contribution of women to the preservation of life is not taken into account, and the question of a possible overlap of gender differences with the differentiation of nature and culture is ignored.he second possibility is that the differentiation is not wholly successful and that a zone comes into being in which this indistinguishability is materialized. This is the case in the constitution of the so-called “homo sacer”. Homo sacer is the abbreviated formulation for a much-discussed and variously interpreted sentence from archaic Roman law. In the law of Twelve Tables (8, 21), he who as patron deceives his clients is declared to be sacer, outlawed, without peace.gamben bases his interpretation of homo sacer on Pompeius Festus’ lexicon, according to which homo sacer is a man who is condemned for a crime and killed but may not be sacrificed. The homo sacer is, in a sense, free game. Agamben equates him with the condemned and interprets him as the representative, the embodiment, of “bare life”, of the bare life released in the sovereign act of constituting the law. This historical phase begins with archaic Roman law and lasts until institution of the Habeas Corpus Act in 1679. This act allowed anyone under arrest to bring his case before the court within three days. The goal was to limit arbitrary arrests. Literally, it means that everyone who holds someone under arrest is required personally to bring the arrested party before the court within three days. For Agamben, with this legal formulation, which is focused on physical presence, the body becomes a political subject. The role of representing bare life is transferred to this body, and with this, according to Agamben, begins the last phase of Western history.