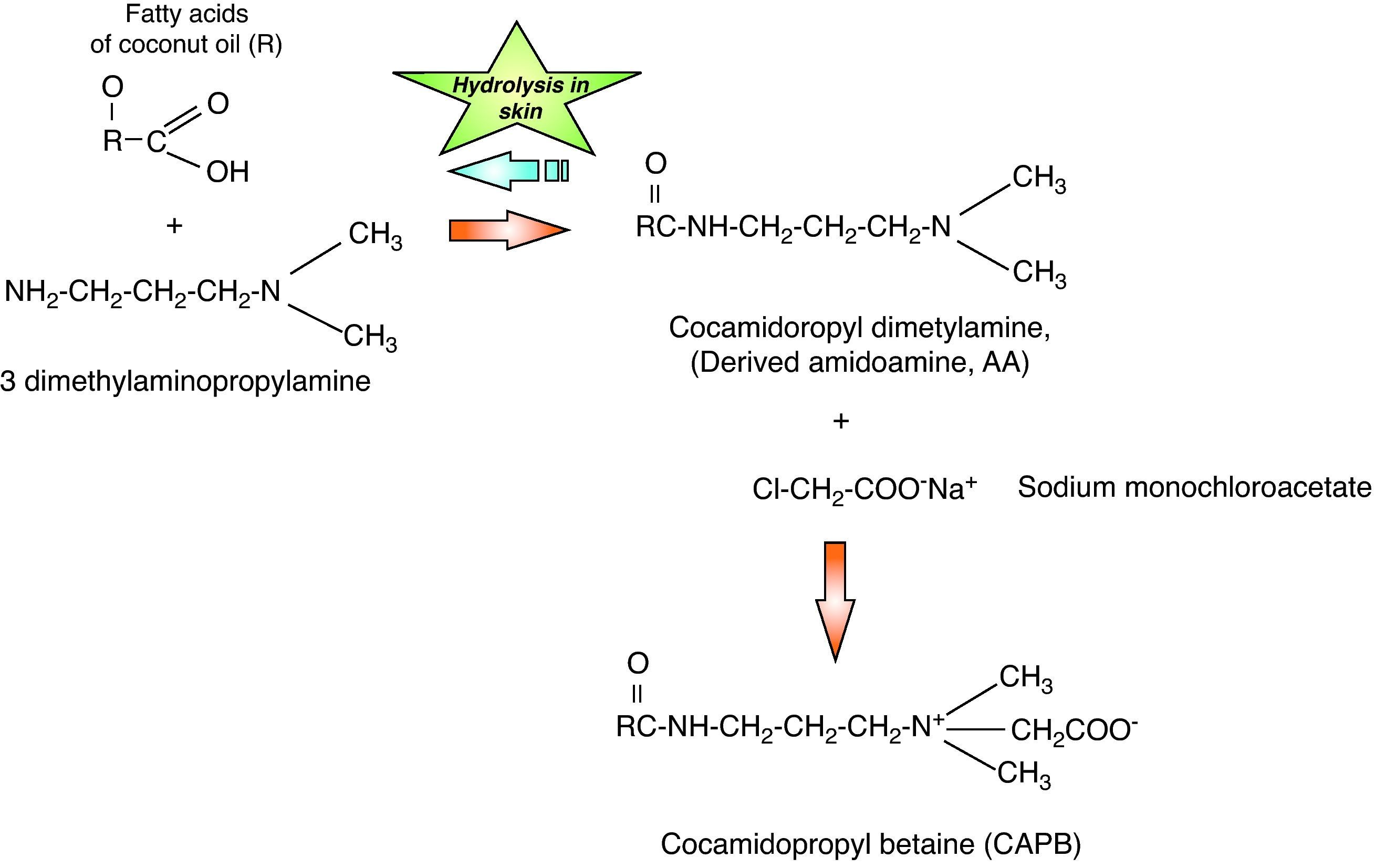

Shampoos, soaps and intimate hygiene products have been considered infrequent causes of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) because they are preparations eliminated with water and their permanence on the skin is very brief. Allergens usually contained have a low sensitising capacity due to their low concentration and brief contact. An exception to this rule is cocamidopropyl betaine (CAPB), a non-ionic tensoactive agent that has been a relatively frequent cause of ACD to shampoos and other products that are eliminated with water in Europe and the US in the last 20 years.1 Currently, the advantages of synthetic detergent based products have gradually resulted in their greater popularity over common soaps. Recent studies in the US, Australia and Israel, suggest that CAPB allergy persists as a clinical problem, and that such compounds should be included among extracts used in standardised cutaneous patch tests.2 Detergents in general contain tensoactive agents which are believed to decrease water's superficial tension. On the other hand, surfactants are classified by their ionic properties in water as anionic, cationic, non-ionic or amphoteric.3 Amphoteric surfactants, of which betaine is the classical example, contain elements with both positive and negative charges within a same molecular structure, producing less irritant effects than those anionic tensoactive agents. CAPB is the main non-ionic tensoactive agent that contains ammonia and was originally introduced in personal hygiene products by Johnson & Johnson® in 1967 with the “no more tears” characteristic, mainly in children's shampoo ingredients. CABP is composed of a combination of fatty acids obtained from coconut oil with 3-dimethylamine propylamine (DMAPA). The initial substance obtained is cocamidopropyl dimethylamine, which is an amidoamine derivative (AA). The AA is then processed with sodium monochloroacetate, obtaining the final product: CABP (Fig. 1). The purpose of CABP addition to personal hygiene products is as a foam booster, thickener and softener.3 Since the beginning of the 1980s, a series of reports have appeared, indicating the CABP may act as a contact allergen. The sensitisation prevalence to this substance is currently unknown in our country, however, a high frequency of sensitisation is known to present in hair dressers and those people who use shampoos, liquid soaps, hair dyes, contact lens solutions, shower gels and skin cleansers, given the presence of this component in these products.2,4 It must be highlighted that various studies have demonstrated that the true sensitising agents could be intermediate products in the synthesis of CABP such as DMAPA and AA, more than CAPB itself. During many years this issue has been highly controversial and numerous North American studies5–7 have demonstrated that AA was the cause of DCA while numerous European studies8,9 show that DMAPA is the true sensitising substance. In our milieu, in which we probably have an under-registration of sensitisation to this substance, the purpose of the present study is to describe the role of CABP as a cause of ACD.

A 61-year-old patient presented with a six month history of pruriginous lesions on the cheeks and chin (Fig. 2), without occupational related risk factors and no history of atopia. Topical steroids had been used with clinical response, but presented with frequent relapses consisting of desquamative erythematous lesions at the sites previously described. An epicutaneous test (patch test) was applied on the upper back with the American standard series (Trolab® Patch Test Allergens) and improved quality chamber (Finn Chambers® for Patch Testing), showing a ++ positive reaction the D1 to CABP, balsam of Peru, balsam of Tolu and mixed fragrances, which persisted until D2 reading. The interview following the tests allowed for identification of a daily use of shaving shampoo containing CABP. Avoidance of this product during the skin care regimen resulted in resolution of the skin lesions and associated symptoms. The patient was finally diagnosed with an ACD to CABP present in the commercial CABP (shampoo).

To date, this is the first Colombian case report to describe ACD produced by sensitisation to CABP in a patient who routinely used liquid soap during shaving. Sensitisation to CABP clinically presents as a recurrent chronic dermatitis that involves the head (scalp, face and eyelids) and neck. International case reports exist which describe occupational ACD in hair dressers and health care personnel who present with forearm and hand involvement10. However, more diffuse presentations may present when liquid soaps, shampoos and shower gels are used, as in our case. With respect to CABP sensitisation, various studies have used allergenic extracts in the intermediate product of CABP synthesis patch test in patients allergic to this substance. Of these, DMAPA has been concluded to possibly have a significant role in CABP allergy.8 In our country, these intermediate substances are not available, which limits the determination of these elements (DMAPA or AA) as causative agents in the clinical manifestations in our case. Given the current conditions of contact dermatitis knowledge in our environment, as is the absence of prevalence studies, this study provides a better understanding of this type of pathologies and specifically with respect to CABP.

Finally, in light of international literature, even though it is important to perform this type of studies, which aid the scientific population in the understanding of allergic cutaneous pathology, we must stress the need for more research studies that provide information regarding the frequency and prevalence of contact allergens in our population with the purpose of intervening with public health measures that impact not only in the health-disease process of our patients, but also in the health-related quality of life.