COX-2 inhibitors are safe alternatives in patients with cross-reactive non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) hypersensitivity. These drugs are recommended to these patients after negative drug provocation tests (DPTs). However, cumulative data on encouraging results about the safety of COX-2 inhibitors in the majority of these patients bring the idea as to whether a DPT is always mandatory for introducing these drugs in all patients with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity.

ObjectiveTo document the safety of COX-2 inhibitors currently available and to check whether or not any factor predicts a positive response.

MethodsThis study included the retrospective analysis of cases with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity who underwent DPTs with COX-2 inhibitors in order to find safe alternatives. DPTs were single-blinded and placebo controlled.

ResultsThe study group consisted of 309 patients. COX-2 inhibitors were well tolerated in the majority of the patients [nimesulide: 91.9%; meloxicam: 90.2%; rofecoxib: 94.9%; and celecoxib: 94.9%)]. Twenty-five patients (30 provocations) reacted to COX-2 inhibitors. None of the factors were found be associated with positive response.

ConclusionOur results suggest to follow the traditional DPT method to introduce COX-2 inhibitors for finding safe alternatives in all patients with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity before prescription as uncertainty of any predictive factor for a positive response continues. However, these tests should be performed in hospital settings in which emergency equipment and experienced personnel are available.

Management of hypersensitivity reactions to drugs is complex and has been a challenging area for allergists. This requires a careful approach which includes the use of drug skin tests and provocation tests mainly oriented on the need of the patients.1–6 In this approach, drug provocation tests (DPTs) are recommended mainly for either diagnosis of drug hypersensitivity or to provide safe alternatives as well as excluding cross-reactivity of related drugs in proven hypersensitivity.4 In this sense, the use of DPTs to provide safe alternatives is much more preferred and used in daily practice.4

The management of patients with hypersensitivity reactions to aspirin and/or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is an important part of daily practice of an allergist. Aspirin and NSAIDs induce a variety of hypersensitivity reactions manifested by pruritus, urticaria, bronchospasm and anaphylaxis in susceptible subjects.5–7 Cross-reactivity between NSAIDs is the most common underlying mechanism in multiple reactors whereas IgE mediated immune response can be responsible in single reactor cases.5–7 The patients with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity are recommended to avoid the culprit analgesic(s) as well as related COX-1 inhibitors and if no contraindication exist, a DPT is performed in order to find safe alternative in accordance with previous suggestions5,6 as they might be in such need. Drugs that do not inhibit COX-1 but COX-2 selectively can be regarded safe in subjects with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity. Supporting this data in clinical practice, there are increasing reports about the safe use of COX-2 inhibitors in patients with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity.8

However, DPTs performed for finding safe alternatives take substantial time and effort on the part of the medical staff and physicians. The cumulative data on encouraging results about the safety of COX-2 inhibitors in these patients might bring the idea of whether a DPT is always mandatory in all patients with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity before prescribing these medications. So, it is particularly important to see the pattern and outcomes of these tests, as predictors of a positive response may guide for further management of patients with similar complaints in the future. However, so far, limited data exists on this topic.

We have been performing single blind placebo controlled DPTs since 1998 in our university hospital. Since then, many patients with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity have been tested for safety of COX-2 inhibitors which were available in the markets at the test time. So, we have a large number of patients to address this issue. In this retrospective evaluation, we primarily aimed to document the safety of COX-2 inhibitors currently available and secondarily to check whether or not any factor predicts a positive response.

MethodsSubjectsThis study included retrospective analysis of the cases who applied to our tertiary care clinic between January 2000 and December 2006 because of aspirin/NSAID hypersensitivity and underwent DPTs with mainly COX-2 inhibitors to find safe alternatives. The study group consisted of the patients with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity. The cases with history of immediate reaction suggestive of an IgE-mediated reaction to a single NSAID (i.e. dipyrone) or non-immediate reactions such as maculopapular rashes, fixed drug eruptions, bullous drug eruptions, contact dermatitis, etc.) were not included in the analysis. Diagnosis was mainly based on both a reliable history of immediate reactions such as urticaria, angio-oedema, upper and lower respiratory symptoms after use of aspirin/NSAIDs as well as positive aspirin provocation tests in a certain number of cases. Cases with a history of severe reactions which occurred at least twice after the use of aspirin/NSAIDs, or those which were not clinically suitable for such testing, were not challenged by aspirin.

Demographics and disease characteristics such as age, gender, history of drug allergy (type of reaction, duration, culprit drug(s)), or the presence of comorbid conditions such as asthma and chronic urticaria were recorded. Asthma was diagnosed by the presence of recurrent symptoms of wheezing, shortness of breath, cough, and demonstration of objective sign of reversible airway obstruction as stated by the NIH guidelines.9 Asthmatic patients were tested if their asthma was in stable period for at least 2 weeks and having a FEV1 value over 70% predicted. Sensitivity to drugs other than analgesics was diagnosed by reliable history of immediate reactions (urticaria/angio-oedema, bronchospasm, laryngeal oedema, rhinitis, and systemic anaphylactic reactions involving hypotension, laryngeal oedema, bronchospasm and/or shock and presence of non-immediate reactions (maculopapular eruption, fixed drug eruption, photosensitivity, contact dermatitis, and other reactions) to a prescribed drug.

Atopy was assessed by prick tests. Skin prick tests (SPTs) were performed using a common panel including Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Dermatophagoides farinae, grass, tree, and weed pollens, cat, dog, Alternaria, cladosporium, and cockroach allergen extracts (Allergopharma/Germany). Positive and negative controls were histamine (10mg/ml) and phenolated glycerol saline, respectively. Skin testing was performed by puncture method and a mean wheal diameter of 3mm or greater than with the control solution was considered positive.

Drug provocation testsDPTs were performed under strict medical surveillance in our hospital setting. Drug provocation tests were not performed in cases who had had the reaction within the previous 4–6 weeks; used a medication that could affect the test outcome such as antihistamines and oral corticosteroids; had active signs of underlying disease such urticaria, uncontrolled asthma (FEV1 value less than 70% of predicted), uncontrolled cardiac, renal or hepatic disease as well as current upper airway infection.

As some of these challenges were performed for research purposes, approval of the local ethical committee was obtained for that particular group of drugs. However, if DPT was part of the routine management, then the patients were informed about the tests and a written signed informed consent was obtained prior to the challenges.

Drug provocation tests were performed in a single-blind placebo-controlled design. Placebo and active drugs were tested on separate days. Placebo challenge consisted of the controlled administration of the divided doses of placebo (lactose) in similar dose intervals with the active drug. If the placebo test was negative, the challenge with active drug consisted of administration of the divided doses of the test drug within 1–2h interval on a separate day. Doses of the drugs commonly used for DPTs were ¼ and ¾ of the therapeutic doses. The final doses were 100mg, 200mg, 25mg, 7.5mg for nimesulide, celecoxib, rofecoxib, meloxicam, respectively. Divided doses of rofecoxib and celecoxib were given with 2-h intervals while it was 1h for nimesulide and meloxicam. During the challenge procedure, blood pressure; FEV1 values; skin, ocular, nasal, and bronchial reactions were monitored after each placebo or active drug dose was given. The patients were kept under medical observation for up to 2h after completing the test in case of negative test. Patients were followed up for 24h to detect a delayed reaction. Then, tests were considered negative if no adverse reaction had occurred in 24h. Tests were considered positive if any sign of hypersensitivity reactions such as urticaria, angio-oedema, laryngeal oedema, hypotension, dyspnoea, nasal symptoms, 20% fall in FEV1 value, anaphylaxis, or other rashes were observed during or after the test. In case of positive reaction, the test was stopped and the patients were treated according to symptoms and were kept under medical observation until all symptoms resolved. The documentation of the DPTs for this study was as follows: test result, if positive, the culprit drug, provocative doses, time, and type of reactions.

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were performed by Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS v.11.0; Chicago, Illinois) for Windows. Numeric values were expressed as mean±SEM whereas nominal values were given as n (%). Non-parametric tests were used due to heterogeneity of the groups. Chi-square tests were used for comparison of nominal values. Assessment of risk factors for developing adverse event to alternative NSAIDs was performed firstly by univariate, and then multivariate analysis. The factors in the multivariate analysis were age, gender, time interval between reaction and testing, presence of asthma, chronic urticaria, other drug hypersensitivity, previous reactions, and culprit drugs. All directional p-values were two-tailed and significance was assigned to values lower than 0.05.

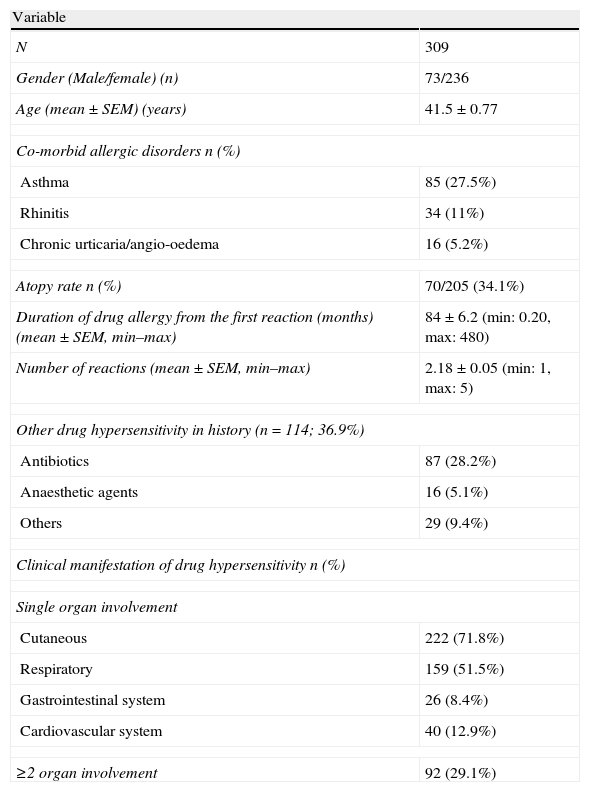

ResultsThe study groupThe study group consisted of 309 patients. The majority of the cases were female (76.3%) and mean age was 41.5±0.77 years (Table 1). Almost one in three patients had asthma and were atopic, based on SPT results. One hundred and fourteen patients had additional drug hypersensitivity, with antimicrobial drugs being the most common. Considering the clinical manifestation of hypersensitivity reactions, urticaria, and respiratory symptoms were the most common (Table 1).

Demographics and disease characteristics of the study group.

| Variable | |

| N | 309 |

| Gender (Male/female) (n) | 73/236 |

| Age (mean±SEM) (years) | 41.5±0.77 |

| Co-morbid allergic disorders n (%) | |

| Asthma | 85 (27.5%) |

| Rhinitis | 34 (11%) |

| Chronic urticaria/angio-oedema | 16 (5.2%) |

| Atopy rate n (%) | 70/205 (34.1%) |

| Duration of drug allergy from the first reaction (months) (mean±SEM, min–max) | 84±6.2 (min: 0.20, max: 480) |

| Number of reactions (mean±SEM, min–max) | 2.18±0.05 (min: 1, max: 5) |

| Other drug hypersensitivity in history (n=114; 36.9%) | |

| Antibiotics | 87 (28.2%) |

| Anaesthetic agents | 16 (5.1%) |

| Others | 29 (9.4%) |

| Clinical manifestation of drug hypersensitivity n (%) | |

| Single organ involvement | |

| Cutaneous | 222 (71.8%) |

| Respiratory | 159 (51.5%) |

| Gastrointestinal system | 26 (8.4%) |

| Cardiovascular system | 40 (12.9%) |

| ≥2 organ involvement | 92 (29.1%) |

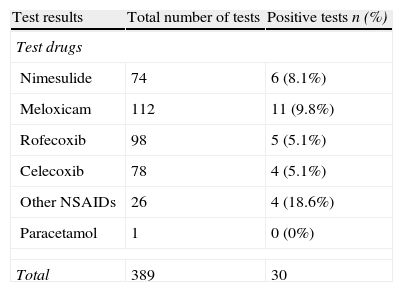

Three hundred and nine patients were challenged with 389 drugs. Overall, 30 provocations (n=25) were positive to at least one of these alternatives. Considering the subgroup analysis, COX-2 inhibitors were usually well tolerated in the majority of the patients (nimesulide: 91.9%, meloxicam: 90.2%, rofecoxib: 94.9%, and celecoxib: 94.9%) (Table 2).

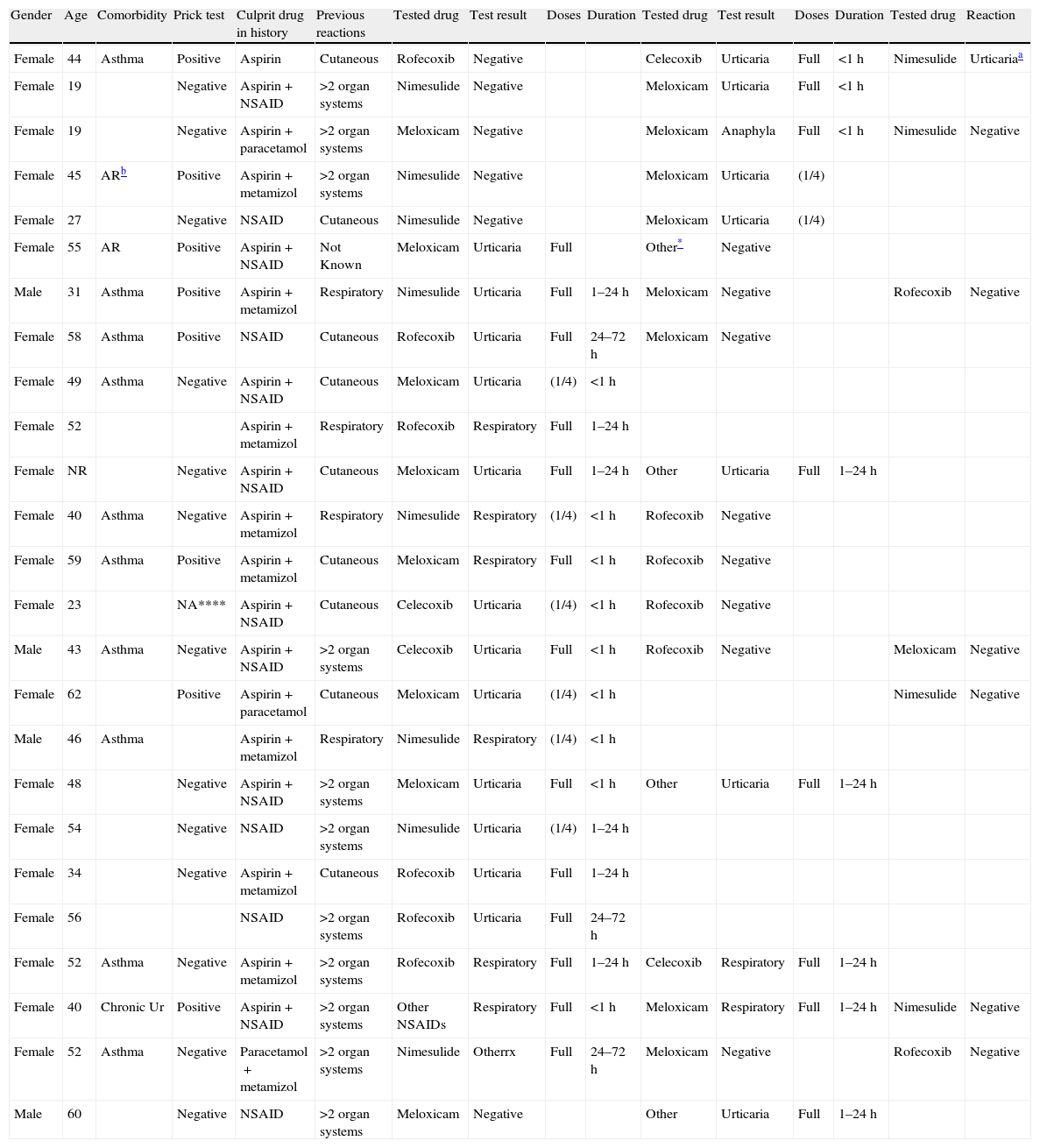

Among 30 positive provocations; the most common clinical symptom was urticaria and/or angio-oedema (18 (68%)) (Table 3). Eight cases developed bronchospasm, whereas only a single case who was tested with meloxicam exhibited anaphylaxis without shock. The majority of the reactions occurred at the full therapeutic doses (22 (73%)). Thirteen reactions (43%) occurred within 1h following the test dose and only two cases showed delayed appearance urticaria after 24h of the full doses. All of the reactions were treated according to the symptoms and the patients were kept in observation in the hospital until complete recovery was achieved. None of the cases required hospitalisation for these reactions.

The characteristics of the patients with positive drug challenges.

| Gender | Age | Comorbidity | Prick test | Culprit drug in history | Previous reactions | Tested drug | Test result | Doses | Duration | Tested drug | Test result | Doses | Duration | Tested drug | Reaction |

| Female | 44 | Asthma | Positive | Aspirin | Cutaneous | Rofecoxib | Negative | Celecoxib | Urticaria | Full | <1h | Nimesulide | Urticariaa | ||

| Female | 19 | Negative | Aspirin+NSAID | >2 organ systems | Nimesulide | Negative | Meloxicam | Urticaria | Full | <1h | |||||

| Female | 19 | Negative | Aspirin+paracetamol | >2 organ systems | Meloxicam | Negative | Meloxicam | Anaphyla | Full | <1h | Nimesulide | Negative | |||

| Female | 45 | ARb | Positive | Aspirin+metamizol | >2 organ systems | Nimesulide | Negative | Meloxicam | Urticaria | (1/4) | |||||

| Female | 27 | Negative | NSAID | Cutaneous | Nimesulide | Negative | Meloxicam | Urticaria | (1/4) | ||||||

| Female | 55 | AR | Positive | Aspirin+NSAID | Not Known | Meloxicam | Urticaria | Full | Other* | Negative | |||||

| Male | 31 | Asthma | Positive | Aspirin+metamizol | Respiratory | Nimesulide | Urticaria | Full | 1–24h | Meloxicam | Negative | Rofecoxib | Negative | ||

| Female | 58 | Asthma | Positive | NSAID | Cutaneous | Rofecoxib | Urticaria | Full | 24–72h | Meloxicam | Negative | ||||

| Female | 49 | Asthma | Negative | Aspirin+NSAID | Cutaneous | Meloxicam | Urticaria | (1/4) | <1h | ||||||

| Female | 52 | Aspirin+metamizol | Respiratory | Rofecoxib | Respiratory | Full | 1–24h | ||||||||

| Female | NR | Negative | Aspirin+NSAID | Cutaneous | Meloxicam | Urticaria | Full | 1–24h | Other | Urticaria | Full | 1–24h | |||

| Female | 40 | Asthma | Negative | Aspirin+metamizol | Respiratory | Nimesulide | Respiratory | (1/4) | <1h | Rofecoxib | Negative | ||||

| Female | 59 | Asthma | Positive | Aspirin+metamizol | Cutaneous | Meloxicam | Respiratory | Full | <1h | Rofecoxib | Negative | ||||

| Female | 23 | NA**** | Aspirin+NSAID | Cutaneous | Celecoxib | Urticaria | (1/4) | <1h | Rofecoxib | Negative | |||||

| Male | 43 | Asthma | Negative | Aspirin+NSAID | >2 organ systems | Celecoxib | Urticaria | Full | <1h | Rofecoxib | Negative | Meloxicam | Negative | ||

| Female | 62 | Positive | Aspirin+paracetamol | Cutaneous | Meloxicam | Urticaria | (1/4) | <1h | Nimesulide | Negative | |||||

| Male | 46 | Asthma | Aspirin+metamizol | Respiratory | Nimesulide | Respiratory | (1/4) | <1h | |||||||

| Female | 48 | Negative | Aspirin+NSAID | >2 organ systems | Meloxicam | Urticaria | Full | <1h | Other | Urticaria | Full | 1–24h | |||

| Female | 54 | Negative | NSAID | >2 organ systems | Nimesulide | Urticaria | (1/4) | 1–24h | |||||||

| Female | 34 | Negative | Aspirin+metamizol | Cutaneous | Rofecoxib | Urticaria | Full | 1–24h | |||||||

| Female | 56 | NSAID | >2 organ systems | Rofecoxib | Urticaria | Full | 24–72h | ||||||||

| Female | 52 | Asthma | Negative | Aspirin+metamizol | >2 organ systems | Rofecoxib | Respiratory | Full | 1–24h | Celecoxib | Respiratory | Full | 1–24h | ||

| Female | 40 | Chronic Ur | Positive | Aspirin+NSAID | >2 organ systems | Other NSAIDs | Respiratory | Full | <1h | Meloxicam | Respiratory | Full | 1–24h | Nimesulide | Negative |

| Female | 52 | Asthma | Negative | Paracetamol+metamizol | >2 organ systems | Nimesulide | Otherrx | Full | 24–72h | Meloxicam | Negative | Rofecoxib | Negative | ||

| Male | 60 | Negative | NSAID | >2 organ systems | Meloxicam | Negative | Other | Urticaria | Full | 1–24h |

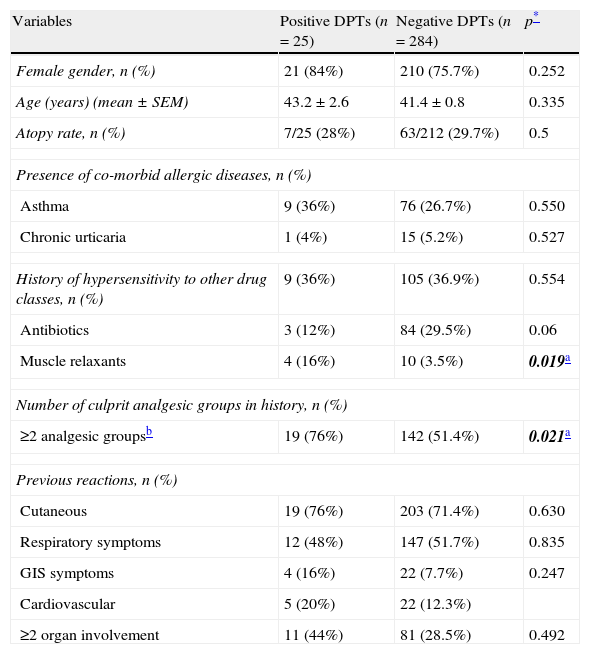

In the univariate analysis, the patients with positive DPTs to alternative drugs had more frequent hypersensitivity reactions to muscle relaxants and had reactions to at least two different groups of analgesics (Table 4). However, none of the variables were found to be significant after multivariate analysis.

Comparison of demographics and disease characteristics of the subjects with positive and negative drug provocation tests.

| Variables | Positive DPTs (n=25) | Negative DPTs (n=284) | p* |

| Female gender, n (%) | 21 (84%) | 210 (75.7%) | 0.252 |

| Age (years) (mean±SEM) | 43.2±2.6 | 41.4±0.8 | 0.335 |

| Atopy rate, n (%) | 7/25 (28%) | 63/212 (29.7%) | 0.5 |

| Presence of co-morbid allergic diseases, n (%) | |||

| Asthma | 9 (36%) | 76 (26.7%) | 0.550 |

| Chronic urticaria | 1 (4%) | 15 (5.2%) | 0.527 |

| History of hypersensitivity to other drug classes, n (%) | 9 (36%) | 105 (36.9%) | 0.554 |

| Antibiotics | 3 (12%) | 84 (29.5%) | 0.06 |

| Muscle relaxants | 4 (16%) | 10 (3.5%) | 0.019a |

| Number of culprit analgesic groups in history, n (%) | |||

| ≥2 analgesic groupsb | 19 (76%) | 142 (51.4%) | 0.021a |

| Previous reactions, n (%) | |||

| Cutaneous | 19 (76%) | 203 (71.4%) | 0.630 |

| Respiratory symptoms | 12 (48%) | 147 (51.7%) | 0.835 |

| GIS symptoms | 4 (16%) | 22 (7.7%) | 0.247 |

| Cardiovascular | 5 (20%) | 22 (12.3%) | |

| ≥2 organ involvement | 11 (44%) | 81 (28.5%) | 0.492 |

In this study, COX-2 inhibitors were well tolerated in the majority of patients with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity. The reactions seen in a small subset of patients were usually mild and after a full therapeutic dose of drugs. However, no predictive factors for positive tests with alternative COX2 inhibitors were defined. So, although the safety profile of DPTs for the purpose of finding safe alternatives was within acceptable limits, our results indicated that DPTs are still necessary before introducing these drugs to the patients with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity.

The studies cumulating in the last decade suggested safe use of COX-2 inhibitors as a choice of suitable alternative drugs in patients with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity. Nimesulide, a NSAID that preferentially inhibits COX-2, was among the first marketed in many countries. Initial studies showed favourable results with this drug as a safe alternative in this particular group of patients.10–14 Later on, studies with rofecoxib and celecoxib, selective COX-2 inhibitors, provided better results in terms of safety in these patients.15–22 However, owing to documentation of high cardiotoxicity and the risk of sudden death, both medications were withdrawn from the market all around the world in 2003. Following this, reports in favour of the safe use of other COX-2 inhibitors such as meloxicam, valdecoxibe, etoricoxibe, and parecoxibe in these patients continued to be published.23–30

In our daily practice, we perform DPTs with COX-2 inhibitors to patients with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity in order to find safe alternatives for their analgesic/anti-inflammatory needs. Some of our results were published with good success rates for safe uses of nimesulide (92%),12 meloxicam (91%),14,24 celecoxib (100%),20 and rofecoxib (99%).18 Although related data is presented here, the latter two selective COX-2 inhibitors were withdrawn from the markets in our country in parallel to the world in 2003 and are no longer in use. Since then, we have been testing these patients with nimesulide and meloxicam, currently available COX-2 inhibitors in our country. In accordance with previous studies, current results of this study also suggested encouraging results to use these medications as alternative NSAIDs in patients with history of cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity, after their tolerability was tested by DPT.

The majority of the reactions against COX-2 inhibitors were cutaneous and mainly observed within the first hour following the administration of usually full therapeutic doses. However, a single case developed anaphylaxis, but, none of the cases had anaphylactic shock. So far, predictive factors for a positive response to alternative drugs in patients with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity were studied only in few studies and in a limited number of cases. While some studies documented some factors to be a risk for developing such reactions to alternative COX-2 inhibitors, such as: female gender, atopy and history of antimicrobial drug allergy, history of anaphylactic reactions with culprit drug,31–33 others did not.24 Our results, derived from a large number of patients studied in this area, were in favour of the studies indicating no predictive factors for development of hypersensitivity reactions with alternative COX-2 inhibitors. So, a reasonable approach in these patients is still to perform DPTs in a way recommended in the literature and see the full safety of the drug before prescription. These tests should be performed in hospital settings in which emergency equipment and experienced personnel are available and the patients should be observed for a certain period of time after completing the tests.

Depending on the severity of underlying asthma as well as the presence of co-morbid nasal polyps/chronic rhinosinusitis, the risk of analgesic hypersensitivity varies between 10 and 70% in patients with asthma.5,6 On the other hand, approximately 30% of the patients with chronic urticaria develop flares when they intake aspirin or other NSAIDs.7 So, underlying diseases such as asthma, nasal polyps or chronic urticaria are risk factors for adverse events with analgesics that mainly inhibit COX-1. However, contrary to this data, the studies on use of COX-2 inhibitors as alternative drugs as well as the results of the current study clearly showed that these drugs were well tolerated in the majority of cases in both group of patients and neither underlying asthma nor chronic urticaria are risk factors for developing hypersensitivity reactions to alternative drugs. Atopic individuals are expected to develop more reactions to a drug when DPTs were performed for diagnostic purpose.34 Although atopy was stated as a risk factor for developing hypersensitivity reactions to alternative COX-2 inhibitors in one of the earlier studies,33 our results failed to show such a relationship.

We did not have the details of the severity of drug-related reactions because of the retrospective nature of the study. Patients with a history indicating at least two separate episodes of severe asthma attack which required emergency room admission was shown to have positive aspirin provocation when tested.5,6,35 Therefore, it could be of interest to determine whether or not the severity of symptoms i.e. dyspnoea, could also predict the positive response to drugs in finding safe alternatives.

In this study, we performed these tests when the majority of the cases were in good health and did not need the drug tested at the test time. This approach is practically recommended.5 The circumstances as well as the health conditions of the patients when the patients really need this medication may not be appropriate for drug testing. One concern arising from this approach could be whether a negative test result determines the safety of that particular drug in future use. To address this question, in our previous study, we examined the safety of long-term use of COX-2 inhibitors in patients with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity after a negative DPT and showed that use of these medicines was still safe in the majority of the cases and only a few patients described hypersensitivity reactions after a negative DPT,36 which was also supported by other authors.37–39 So, one may say that the negative predictive value of these tests is very high to predict the long-term use in safe conditions.

In summary, our results once again indicated the safety of COX-2 inhibitors as alternative NSAIDs in a significant number of patients with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity. However, our data also revealed that a positive response to alternative COX-2 cannot be predicted by pre-test diseases characteristics in patients with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity. So it is hard to say when or how the patients will react to these unique drugs. This data still suggests to follow the traditional way of DPTs to introduce these drugs to all patients with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity before prescription. However, particular attention must be paid to the awareness of the primary care physicians about this issue as they had a tendency to prescribe the COX-2 inhibitors more frequently because of less gastrointestinal side effects.40 So, awareness needs to be developed for this group to not prescribe COX-2 inhibitors directly to their patients with cross-reactive NSAID hypersensitivity without seeing a negative DPT result. However, these tests should definitely be performed in hospital settings in which emergency equipment and trained personnel are available.

Ethical disclosuresPatients’ data protectionThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence is in possession of this document.

Protection of human subjects and animals in researchThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Funding sourceNo financial support was provided for this study. Study investigators covered all of the expenses individually.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest related to manuscript.