Asthma and other wheezing disorders are common chronic health problems in childhood. We aim to evaluate whether the attendance by children under three years of age to day-care centers is a protector or risk factor in the development of recurrent wheezing or asthma in the following years of their lives.

MethodsSystematic review of published cohort or cross-sectional studies, without any time limitation. We searched in PubMed, Cinhal, Cuiden and Scopus (EMBASE included). The quality of the studies was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Disagreements were solved by mutual consensus. Weighted odds ratio (ORs) were estimated using RevMan 5.3, following random effects models.

ResultsWe selected 18 studies for qualitative analysis, nine cohort studies and nine cross-sectional studies. Day-care center attendance is associated with an increased risk of early recurrent wheezing (four studies; 50,619 subjects; adjusted OR 1.87 [1.21 to 2.88]; I2 91%) and asthma before the age of six (five studies; 5412 subjects; adjusted OR 1.59 [1.26 to 2.01]; I2 0%), but not later (five studies; 5538 subjects; adjusted OR 0.86 [0.55 to 1.32]; I2 76%).

ConclusionsChildren attending day-care center during the first years of life have a higher risk of recurrent wheezing during the first three years and asthma before the age of six, but not later. This risk must be taken into account to inform parents in order to choose what kind of care children should have throughout infancy and to implement preventive measures to reduce its impact.

Asthma and other wheezing disorders are common chronic health problems in childhood, placing a great burden on children, their families and society. Several genetic and environmental factors are involved in the development of asthma, but only some of them are modifiable. Any information about risk and protective factors of asthma is thus a priority for public health.

Children attending day-care centers are known to have more frequent infections than those who remain at home.1 As a result of these infections, children who are exposed to infections have more early wheezing episodes, but it is not clear if they have an increased or reduced risk of asthma in late childhood and adult life.2–4

A risk reduction has been explained by the hygiene hypothesis, which proposes that early life exposures influence immune system development, altering the maturation of the immune system by favoring Th2-biased allergic responses during childhood and lowering the risk of asthma.5,6

Three general phenotypes of asthma/wheezing have previously been proposed and are now widely recognized: “transient early wheezing” associated with lower respiratory tract infections during the first three years of life, but not after; “late-onset wheezing” beginning after three years of age; and “persistent wheezing” starting before age three and continuing throughout childhood.7 It is important in order to distinguish between these phenotypes in epidemiological studies to establish the role of time-dependent exposures, as child-day care, in the risk of asthma.

The objective of this systematic review is to evaluate whether the attendance by children under three to day-care centers is a protector or risk factor in the development of recurrent wheezing or asthma in the following years of their lives.

MethodsThis systematic review was carried out from November 2016 to May 2017 by two authors, without limits of time. The inclusion criteria were: cohort or cross-sectional studies which included 0 to 3-year-old children who attended day-care centers and a control group cared at home, with information about whether or not they developed asthma or recurrent wheezing in childhood, adolescence or adulthood. Case-control studies were excluded.

We searched in the following database: PubMed, Cinhal, Cuiden and EMBASE (via Scopus). The searching strategy used in PubMed was: (“Child Day Care Centers”[MeSH] OR (child AND (“day care” OR daycare)) OR “Schools, Nursery”[MeSH] OR Nursery School* OR “family day care” OR “day care homes”) AND (“Asthma” [Mesh] OR Asthma[All Fields] OR “Respiratory Sounds” [Mesh] OR (Wheez*[All Fields])). Similar strategies were used in other databases, with exclusion filters of PubMed articles.

The evaluation of the methodological quality (Newcastle-Ottawa Scale) and the variables of each study were independently carried out by both authors. Disagreements were solved by mutual consensus.

The information gathered for every study was as follows: author, year, design, setting, inclusion and exclusion criteria, measuring day-care center attendance, evaluation of asthma criteria, basal risk, losses, results and limitations.

Statistical analysisCases of recurrent wheezing or asthma in children attending day-care centers or not were extracted from every selected article, taking into account the level of exposure (age of the first attendance and length) and the age of the measurement of the effect. Also, crude and adjusted risk estimates (odds ratio [OR]) were extracted, with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) or calculated from the available data. The data were introduced as Napierian logarithms and their standard errors in RevMan 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration). Available crude and adjusted risk estimates from each study were grouped and analyzed in separate analyses. The three main outcomes were: early recurrent wheezing, asthma both before and after, the age of six. We elaborated Forest-Plot and Funnel-Plot diagrams and estimated weighted ORs and their 95% CI, following random effects models. Heterogeneity was estimated by I2 statistic and publication bias by Funnel-plot inspection. Sensitivity analyses were performed excluding studies in order to explore changes in heterogeneity or weighted estimations. The recommendations of the MOOSE guidelines were followed.

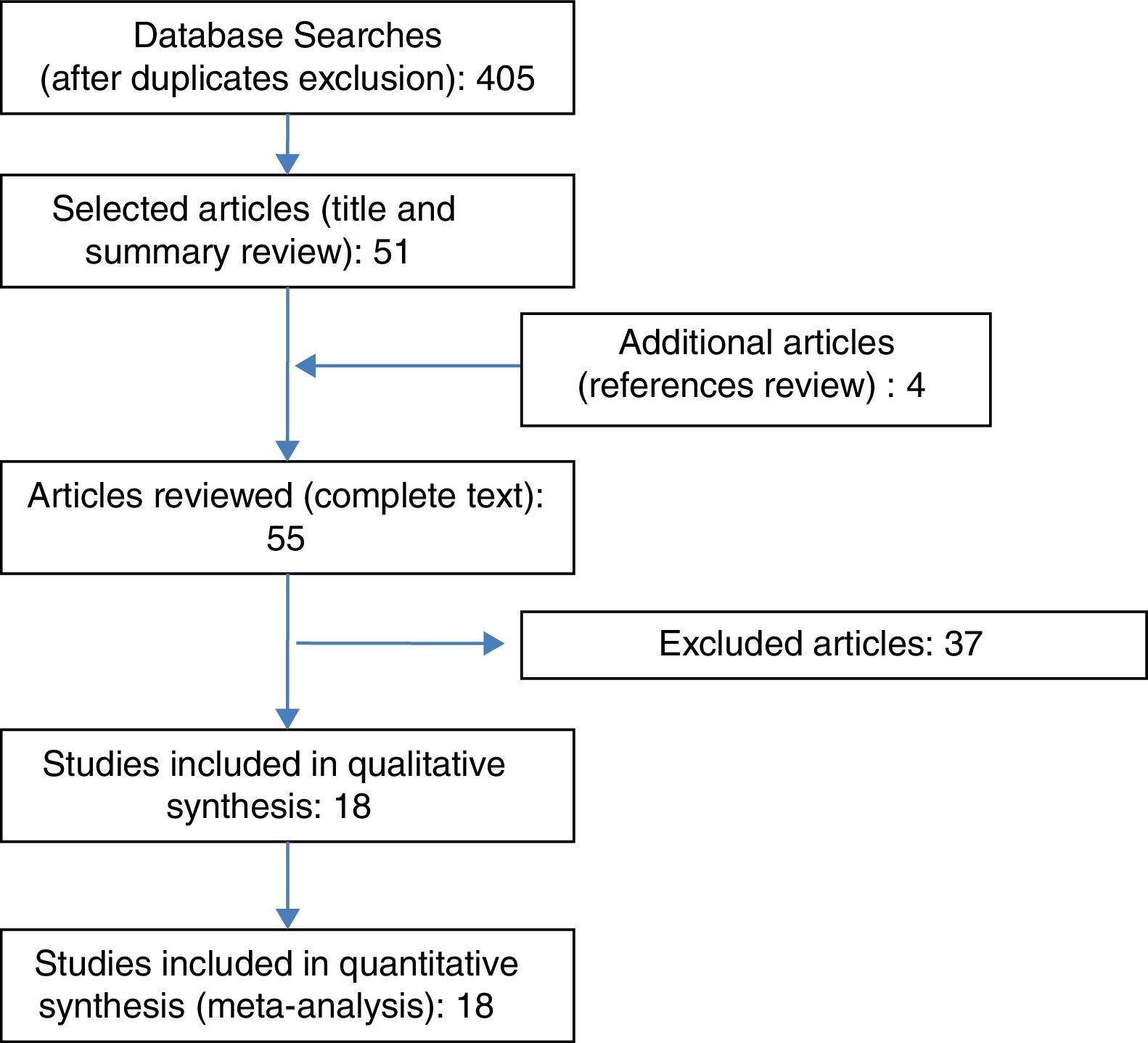

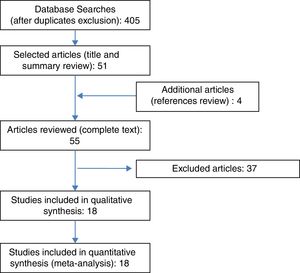

ResultsFig. 1 shows the search flow diagram. Four hundred and five articles were identified, with 51 being selected after reading title and summaries. Four extra articles were added after reviewing the references of the selected articles. We examined 55 complete articles, to check if they accomplished inclusion criteria or not.

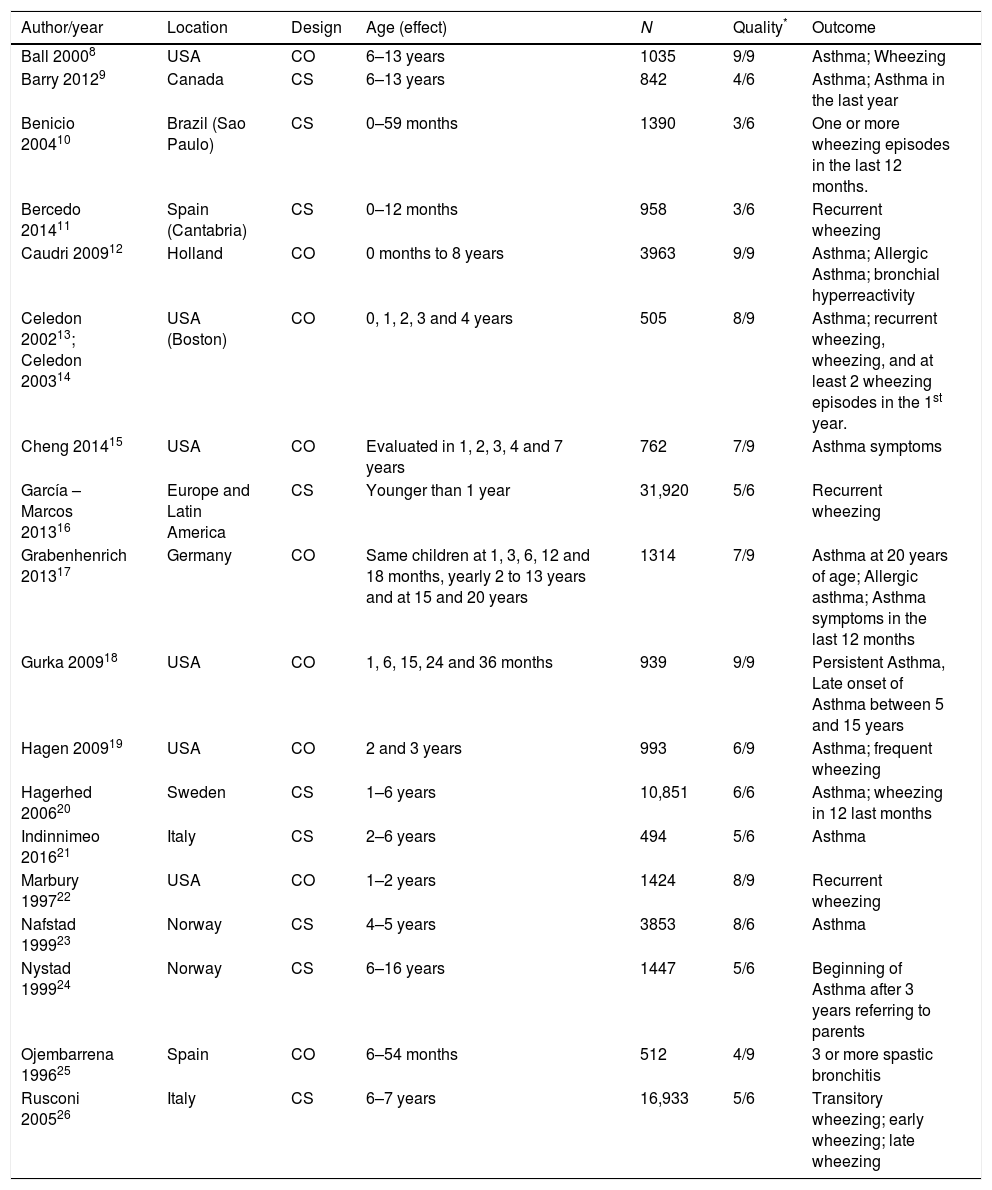

Finally, 18 studies fitted inclusion criteria and were included for qualitative analysis, nine cohort studies and nine cross-sectional studies, which totaled 80,135 children. Table 1 details the number of children with data for each outcome; not all children contributed to all outcomes. The countries where these studies were performed were: USA, Canada, Brazil, Spain, Holland, Germany, Sweden, Italy, Norway and some other countries in Latin America.

Main characteristics of the studies included.

| Author/year | Location | Design | Age (effect) | N | Quality* | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ball 20008 | USA | CO | 6–13 years | 1035 | 9/9 | Asthma; Wheezing |

| Barry 20129 | Canada | CS | 6–13 years | 842 | 4/6 | Asthma; Asthma in the last year |

| Benicio 200410 | Brazil (Sao Paulo) | CS | 0–59 months | 1390 | 3/6 | One or more wheezing episodes in the last 12 months. |

| Bercedo 201411 | Spain (Cantabria) | CS | 0–12 months | 958 | 3/6 | Recurrent wheezing |

| Caudri 200912 | Holland | CO | 0 months to 8 years | 3963 | 9/9 | Asthma; Allergic Asthma; bronchial hyperreactivity |

| Celedon 200213; Celedon 200314 | USA (Boston) | CO | 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 years | 505 | 8/9 | Asthma; recurrent wheezing, wheezing, and at least 2 wheezing episodes in the 1st year. |

| Cheng 201415 | USA | CO | Evaluated in 1, 2, 3, 4 and 7 years | 762 | 7/9 | Asthma symptoms |

| García – Marcos 201316 | Europe and Latin America | CS | Younger than 1 year | 31,920 | 5/6 | Recurrent wheezing |

| Grabenhenrich 201317 | Germany | CO | Same children at 1, 3, 6, 12 and 18 months, yearly 2 to 13 years and at 15 and 20 years | 1314 | 7/9 | Asthma at 20 years of age; Allergic asthma; Asthma symptoms in the last 12 months |

| Gurka 200918 | USA | CO | 1, 6, 15, 24 and 36 months | 939 | 9/9 | Persistent Asthma, Late onset of Asthma between 5 and 15 years |

| Hagen 200919 | USA | CO | 2 and 3 years | 993 | 6/9 | Asthma; frequent wheezing |

| Hagerhed 200620 | Sweden | CS | 1–6 years | 10,851 | 6/6 | Asthma; wheezing in 12 last months |

| Indinnimeo 201621 | Italy | CS | 2–6 years | 494 | 5/6 | Asthma |

| Marbury 199722 | USA | CO | 1–2 years | 1424 | 8/9 | Recurrent wheezing |

| Nafstad 199923 | Norway | CS | 4–5 years | 3853 | 8/6 | Asthma |

| Nystad 199924 | Norway | CS | 6–16 years | 1447 | 5/6 | Beginning of Asthma after 3 years referring to parents |

| Ojembarrena 199625 | Spain | CO | 6–54 months | 512 | 4/9 | 3 or more spastic bronchitis |

| Rusconi 200526 | Italy | CS | 6–7 years | 16,933 | 5/6 | Transitory wheezing; early wheezing; late wheezing |

CO=Cohort study, CS=Cross-sectional study.

The characteristics of the studies included are in Table 1.8–26 Seven studies (52,309 children) offered data of early recurrent wheezing; seven studies (11,125 children) data of asthma before six years of age; and eight studies (23,834) data of asthma after the age of six. Some studies have data for different outcomes. Data from two articles correspond to a single study.13,14

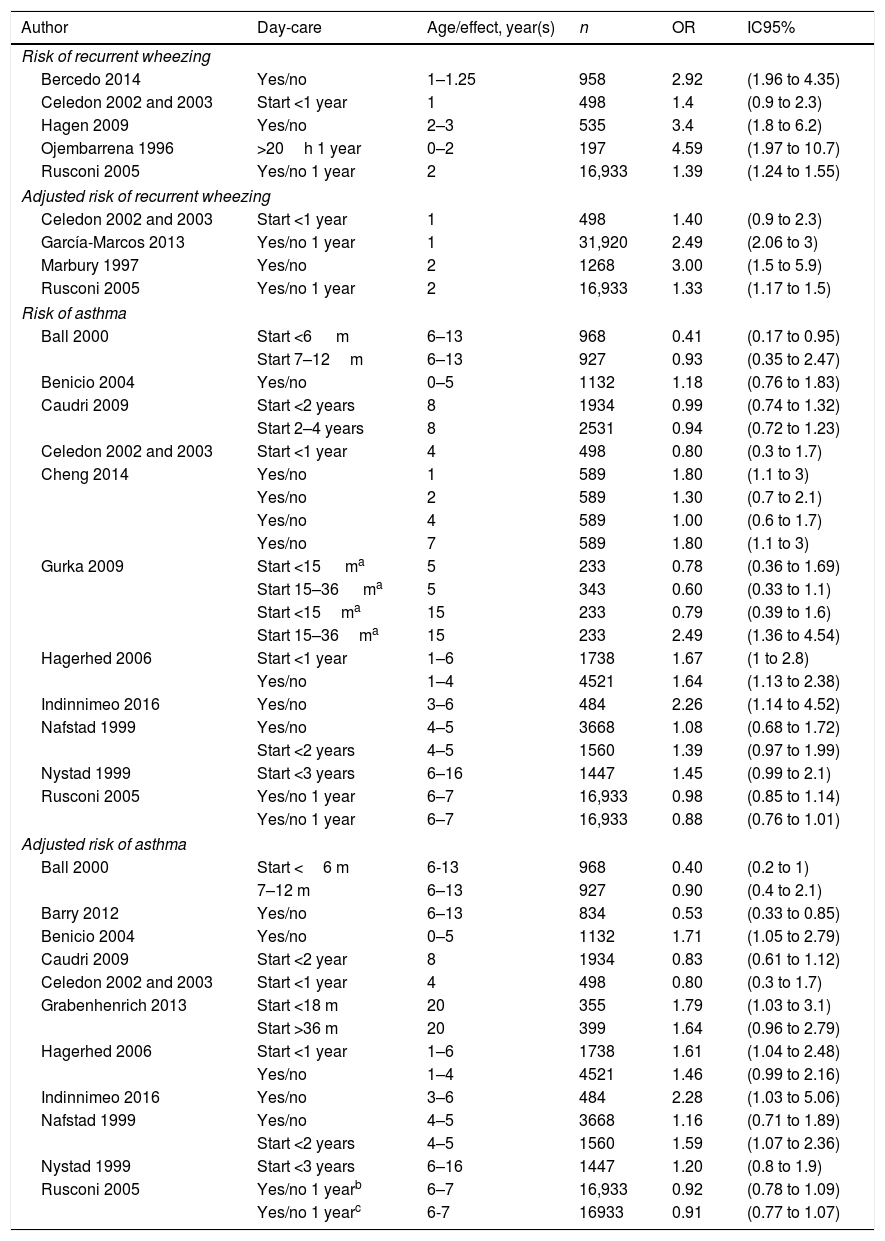

The main study results can be observed in Table 2, with data separated according to each outcome criteria: early recurrent wheezing, asthma before, or after, the age of six.

Results of the studies selected.

| Author | Day-care | Age/effect, year(s) | n | OR | IC95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of recurrent wheezing | |||||

| Bercedo 2014 | Yes/no | 1–1.25 | 958 | 2.92 | (1.96 to 4.35) |

| Celedon 2002 and 2003 | Start <1 year | 1 | 498 | 1.4 | (0.9 to 2.3) |

| Hagen 2009 | Yes/no | 2–3 | 535 | 3.4 | (1.8 to 6.2) |

| Ojembarrena 1996 | >20h 1 year | 0–2 | 197 | 4.59 | (1.97 to 10.7) |

| Rusconi 2005 | Yes/no 1 year | 2 | 16,933 | 1.39 | (1.24 to 1.55) |

| Adjusted risk of recurrent wheezing | |||||

| Celedon 2002 and 2003 | Start <1 year | 1 | 498 | 1.40 | (0.9 to 2.3) |

| García-Marcos 2013 | Yes/no 1 year | 1 | 31,920 | 2.49 | (2.06 to 3) |

| Marbury 1997 | Yes/no | 2 | 1268 | 3.00 | (1.5 to 5.9) |

| Rusconi 2005 | Yes/no 1 year | 2 | 16,933 | 1.33 | (1.17 to 1.5) |

| Risk of asthma | |||||

| Ball 2000 | Start <6 m | 6–13 | 968 | 0.41 | (0.17 to 0.95) |

| Start 7–12m | 6–13 | 927 | 0.93 | (0.35 to 2.47) | |

| Benicio 2004 | Yes/no | 0–5 | 1132 | 1.18 | (0.76 to 1.83) |

| Caudri 2009 | Start <2 years | 8 | 1934 | 0.99 | (0.74 to 1.32) |

| Start 2–4 years | 8 | 2531 | 0.94 | (0.72 to 1.23) | |

| Celedon 2002 and 2003 | Start <1 year | 4 | 498 | 0.80 | (0.3 to 1.7) |

| Cheng 2014 | Yes/no | 1 | 589 | 1.80 | (1.1 to 3) |

| Yes/no | 2 | 589 | 1.30 | (0.7 to 2.1) | |

| Yes/no | 4 | 589 | 1.00 | (0.6 to 1.7) | |

| Yes/no | 7 | 589 | 1.80 | (1.1 to 3) | |

| Gurka 2009 | Start <15 ma | 5 | 233 | 0.78 | (0.36 to 1.69) |

| Start 15–36 ma | 5 | 343 | 0.60 | (0.33 to 1.1) | |

| Start <15ma | 15 | 233 | 0.79 | (0.39 to 1.6) | |

| Start 15–36ma | 15 | 233 | 2.49 | (1.36 to 4.54) | |

| Hagerhed 2006 | Start <1 year | 1–6 | 1738 | 1.67 | (1 to 2.8) |

| Yes/no | 1–4 | 4521 | 1.64 | (1.13 to 2.38) | |

| Indinnimeo 2016 | Yes/no | 3–6 | 484 | 2.26 | (1.14 to 4.52) |

| Nafstad 1999 | Yes/no | 4–5 | 3668 | 1.08 | (0.68 to 1.72) |

| Start <2 years | 4–5 | 1560 | 1.39 | (0.97 to 1.99) | |

| Nystad 1999 | Start <3 years | 6–16 | 1447 | 1.45 | (0.99 to 2.1) |

| Rusconi 2005 | Yes/no 1 year | 6–7 | 16,933 | 0.98 | (0.85 to 1.14) |

| Yes/no 1 year | 6–7 | 16,933 | 0.88 | (0.76 to 1.01) | |

| Adjusted risk of asthma | |||||

| Ball 2000 | Start <6 m | 6-13 | 968 | 0.40 | (0.2 to 1) |

| 7–12 m | 6–13 | 927 | 0.90 | (0.4 to 2.1) | |

| Barry 2012 | Yes/no | 6–13 | 834 | 0.53 | (0.33 to 0.85) |

| Benicio 2004 | Yes/no | 0–5 | 1132 | 1.71 | (1.05 to 2.79) |

| Caudri 2009 | Start <2 year | 8 | 1934 | 0.83 | (0.61 to 1.12) |

| Celedon 2002 and 2003 | Start <1 year | 4 | 498 | 0.80 | (0.3 to 1.7) |

| Grabenhenrich 2013 | Start <18 m | 20 | 355 | 1.79 | (1.03 to 3.1) |

| Start >36 m | 20 | 399 | 1.64 | (0.96 to 2.79) | |

| Hagerhed 2006 | Start <1 year | 1–6 | 1738 | 1.61 | (1.04 to 2.48) |

| Yes/no | 1–4 | 4521 | 1.46 | (0.99 to 2.16) | |

| Indinnimeo 2016 | Yes/no | 3–6 | 484 | 2.28 | (1.03 to 5.06) |

| Nafstad 1999 | Yes/no | 4–5 | 3668 | 1.16 | (0.71 to 1.89) |

| Start <2 years | 4–5 | 1560 | 1.59 | (1.07 to 2.36) | |

| Nystad 1999 | Start <3 years | 6–16 | 1447 | 1.20 | (0.8 to 1.9) |

| Rusconi 2005 | Yes/no 1 yearb | 6–7 | 16,933 | 0.92 | (0.78 to 1.09) |

| Yes/no 1 yearc | 6-7 | 16933 | 0.91 | (0.77 to 1.07) | |

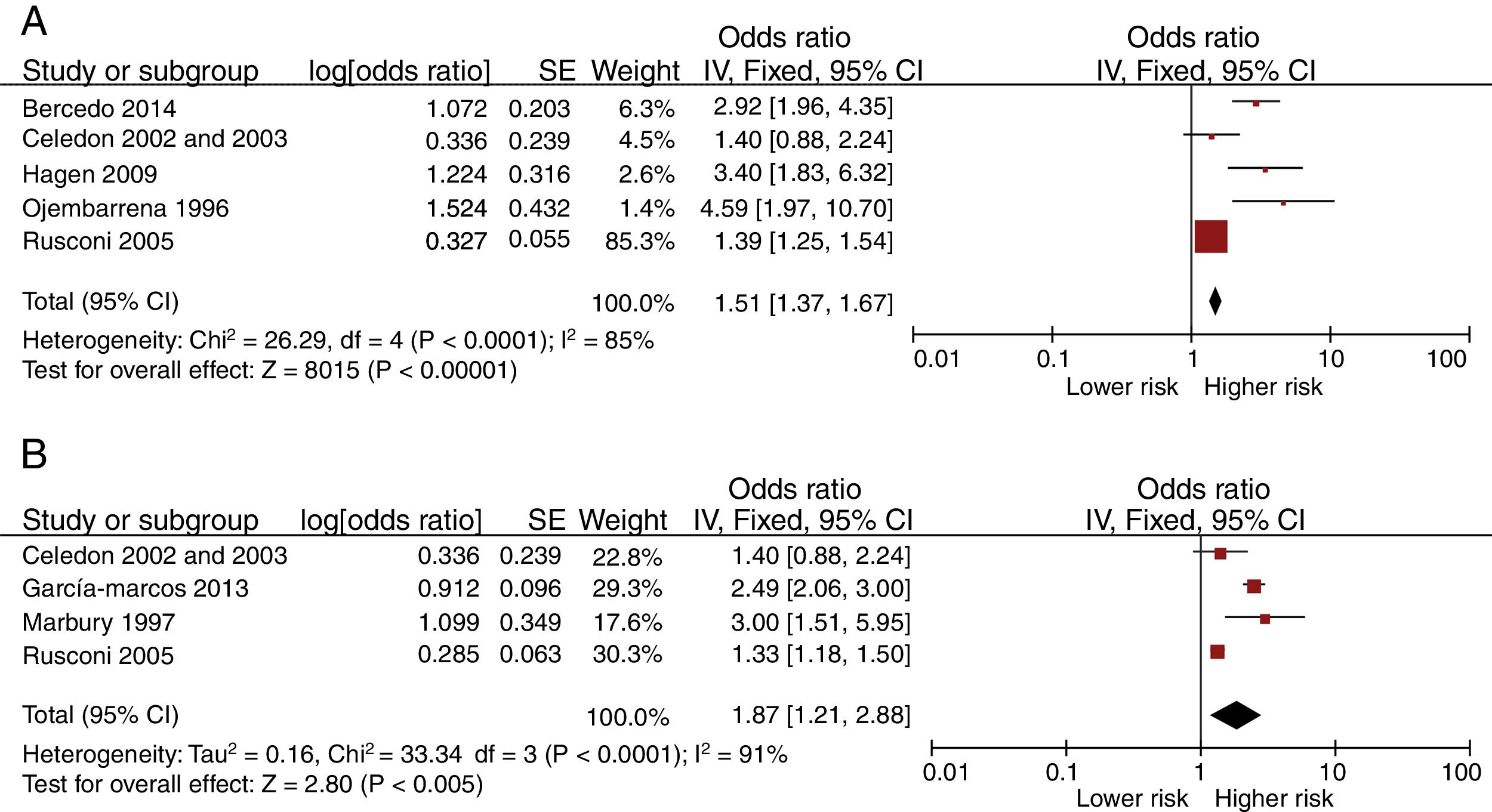

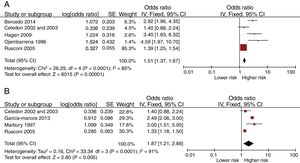

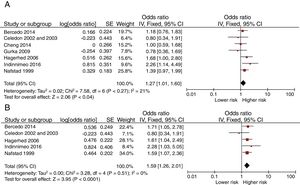

Fig. 2 presents the Forest-plots of the crude and adjusted risk of early recurrent wheezing. Day-care center attendance is associated with an increased risk of early recurrent wheezing (crude OR 1.51 [95% CI: 1.37 to 1.67]; adjusted OR 1.87 [1.21 to 2.88]). The variables included in some of the adjusted analyses were: gender, birth weight, siblings at home, family incomes, maternal education and age, atopic parents, traffic, pets at home, breastfeeding and exposure to smoking.

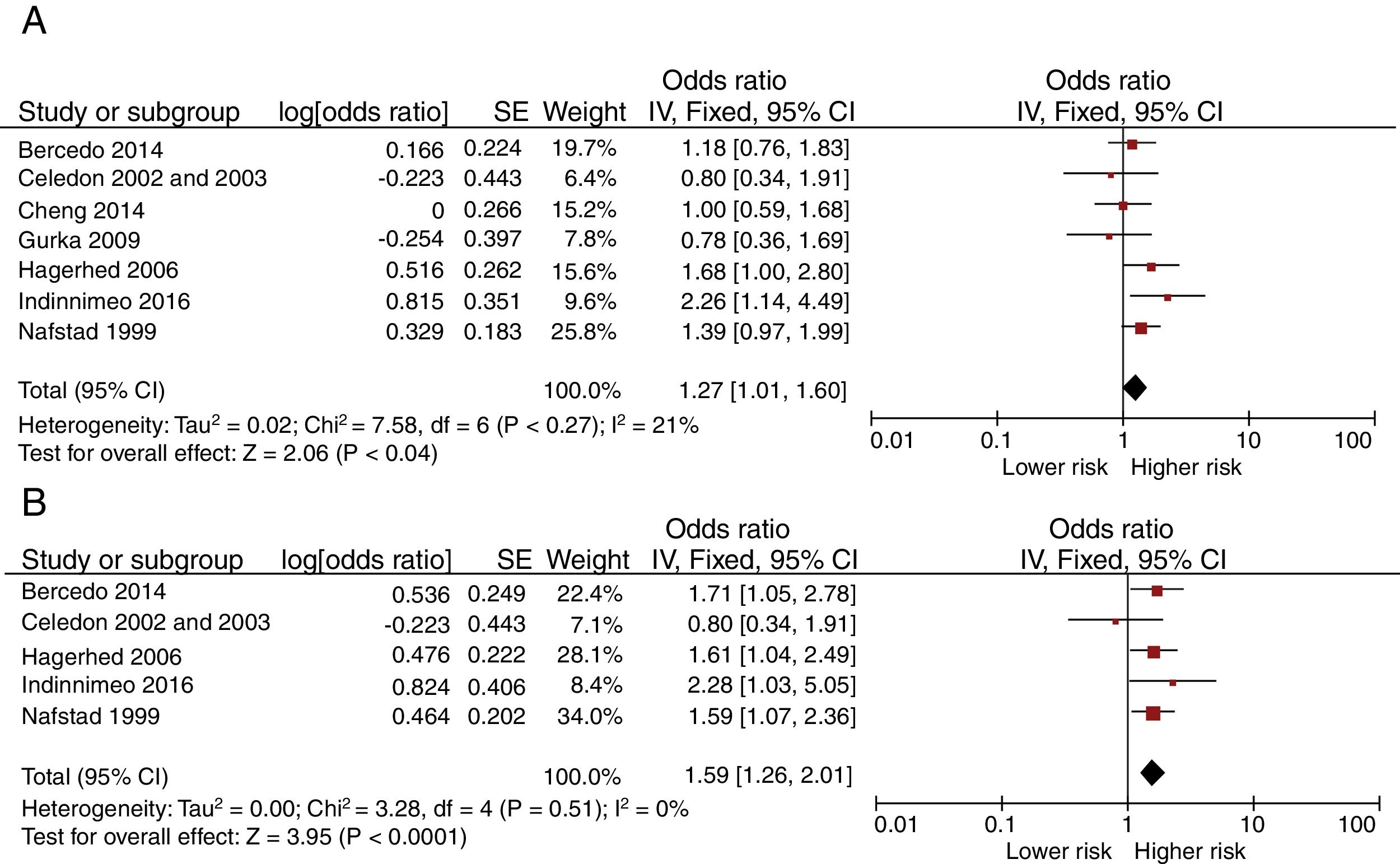

Fig. 3 shows the Forest-plots of the crude and adjusted risk of asthma before the age of six. Day-care center attendance is also associated with an increased risk of asthma before this age (crude OR 1.27 [95% CI: 1.01 to 1.60]; adjusted OR 1.59 [1.26 to 2.01]).

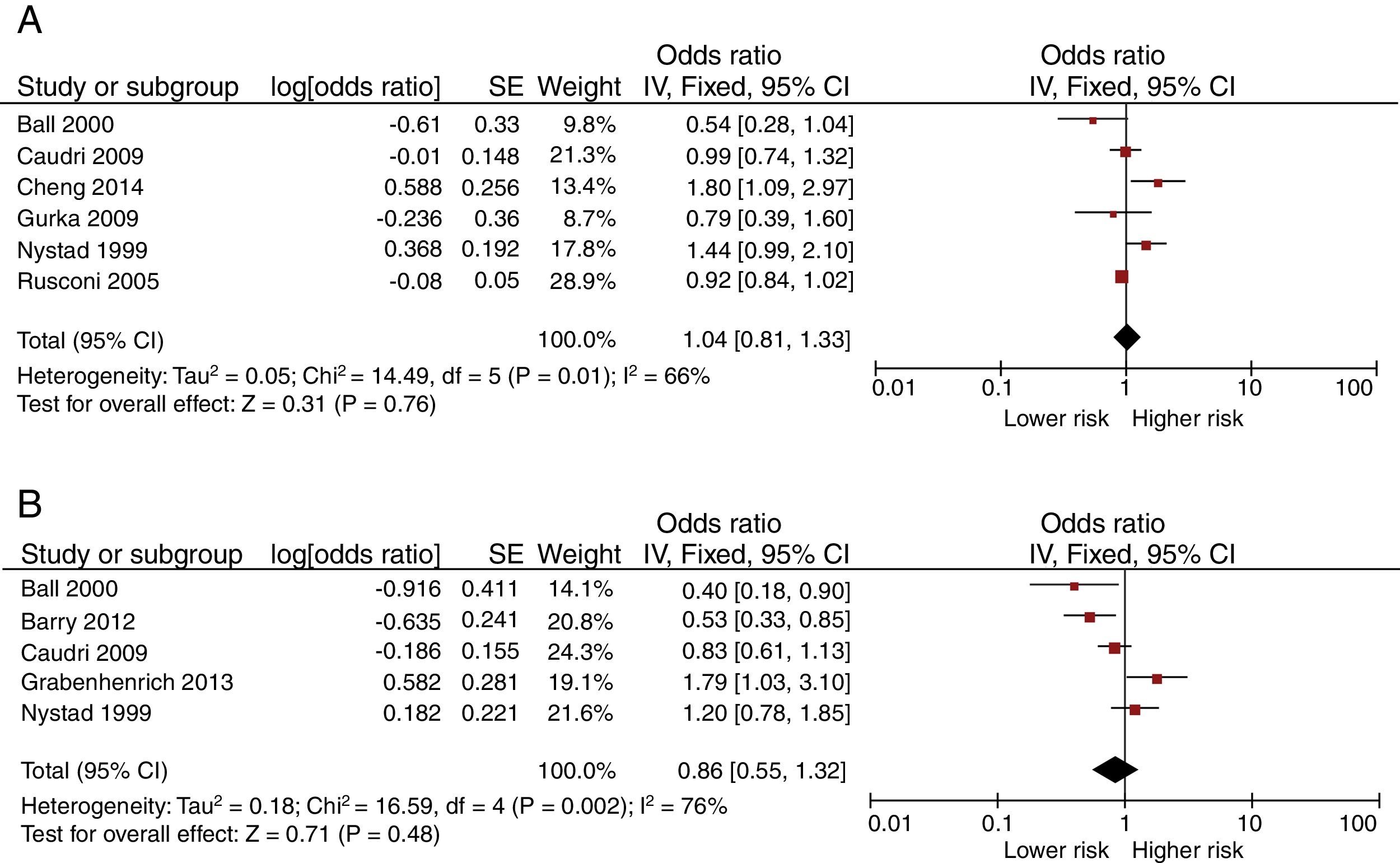

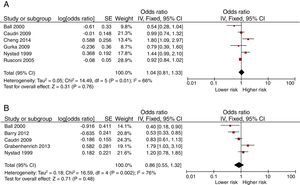

Fig. 4 shows the Forest-plots of the crude and adjusted risk of asthma after the age of six. Day-care center attendance does not seem to be associated with an increased risk (crude OR 1.04 [95% CI: 0.81 to 1.33]; adjusted OR 0.86 [95% CI: 0.55 to 1.32]).

Only the estimations of risk of asthma before six years are homogeneous; other estimations have significant statistical heterogeneity. This heterogeneity was not reduced by exclusion of studies according to its quality nor subgroups analyses by design. Sensitivity analyses did not show changes in the heterogeneity nor in the weighted estimations. Funnel-plot inspection does not suggest major publication bias (data not shown).

DiscussionWe have found that day-care center attendance could be a risk factor for the development of early recurrent wheezing and asthma in the first six years of life. Nevertheless, it seems to be neither a risk factor nor a protection later. The adjusted increase of risk has been estimated at around 87% for early recurrent wheezing and 59% for early asthma. The corresponding attributable fractions are 46.5% and 37.1% (for a 10% basal risk of recurrent wheezing or asthma). These are important figures, taking into account the widely exposed population. The analyzed data do not allow us to suppose that the initial higher risk protects the children from having asthma in later years.

It is unclear if the increase of recurrent wheezing might be exclusive due to a higher frequency of respiratory infections with bronchial involvement, acquired through exposure to other children inside day-care centers or if there is an immune mechanism that provides an atopic response. It is possible that the observed association between the day-care center attendance and asthma diagnosis during the first six years of life may be the result of the transitory recurrent wheezing inclusion, among the asthma cases, rather than an asthma true risk. The criteria used to define asthma in the selected studies are mainly based on the symptoms described by the parents, using different questionnaires. The fact that the risk of having recurrent wheezing or asthma does not continue after the age of six suggests that the effect could be related to early respiratory infections.

Ever since the postulation of the “hygiene hypothesis”, many studies have focused on the relation between day-care and the development of asthma. The results of previous investigations about the risk of asthma in late childhood are conflicting. Our estimations do not show any increase or reduction of this risk. Some of the included studies have found a reduction of asthma risk in later childhood,8,9 but not others. Some studies have analyzed the dose–response relationship of earlier day-care attendance and have also found discordances.8,12

It has been suggested that bacterial or viral infections occurring during infancy, as a result of exposure to numerous children, may interfere to the infant maturing immune system. Within the first six months of life, the immune response of children without atopy shifts from one associated predominantly with type 2 helper T-cells (Th2 cells), like that in adults with atopic illnesses, toward one based more on cytokines derived from type 1 helper T-cells (Th1 cells) like that in adults without atopy. Th1-like response includes the production of interferon-g, which inhibits the proliferation of Th2 cells. Therefore, infections that stimulate a Th1-like response during this critical period of maturation may play an important part by inhibiting the predominantly Th2 response that is present in infants. The absence of such inhibitory signals during infancy may allow the expansion and maturation of Th2 memory cells, resulting in the persistence of a more atopic phenotype.5,27 Nevertheless, these findings have not been contrasted in longer prospective studies; therefore, we do not know if these immune changes are or not permanent.

An alternative explanation for the finding of a relatively lower frequency of asthma episodes in late childhood is that children not attending day-care centers could delay the acquisition of some respiratory infections to this age, with some of these episodes being diagnosed as asthma. Heterogeneity in the environmental and social factors linked with day-care attendance between populations or differences in the gathering exposure data (prospective or retrospective, early or any exposure) could also explain some of the discordances between studies.

There is a high heterogeneity among studies for some estimations, probably due to their observational design and the variability in the measurement of exposure and effect. It implies uncertainty about the magnitude of the risk, but not about its existence. Nevertheless, our estimation of risk of asthma before the age of six is homogeneous enough to be considered valid. Two studies with a large sample size have an important weight in the outcomes of early recurrent wheezing risk and crude asthma risk after the age of six, but sensitivity analyses, excluding these studies, did not change their global estimations. Otherwise, no publication bias has been found. Most of the studies were designed to analyze the risk of recurrent wheezing or asthma, with exposure to day-care center being only one of the factors studied. For this reason, we cannot exclude that some studies have omitted related non-significant data.

The analyses of the studies reveal that children attending day-care center during the first years of life have a higher risk of having recurrent wheezing during the first three years and asthma before the age of six, but not later. This risk must be taken into account to inform patient's parents in order to choose what kind of care children should have throughout infancy.

FundingNo funding source.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.