Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common chronic skin disease in childhood. There is no definitive test for diagnosing AD. The Hanifin-Rajka criteria (HRC) and The United Kingdom Working Party criteria (UKC) are the most used in the literature. It is aimed to evaluate the clinical efficacy of HRC and UKC in pediatric age.

MethodsChildren diagnosed AD in the pediatric allergy clinic were enrolled. Patients with skin problems other than AD were involved as controls. All participants were evaluated for HRC and UKC at the time of diagnosis. Clinical diagnosis by the pediatric allergist was determined as the gold standard.

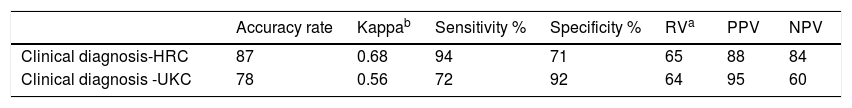

Results200 children with AD and 90 controls were enrolled in the study. Median (interquartile range, IQR) age of AD patients was 13.5 (7–36) months. There was no significant difference in age and sex between groups (p=0.11 and p=0.34, respectively). The HRC were superior to the UKC for sensitivity, negative predictive value, kappa and accuracy rate (94% vs. 72%, 84% vs. 60%, 0.68 vs. 0.56 and 87 vs. 78, respectively). On the other hand, specificity and positive predictive value of UKC were better than those of HRC (92% vs. 71% and 95% vs. 88%, respectively).

ConclusionHRC seem to be better in diagnosing AD than UKC for young children. Further studies are needed to evaluate comparableness of HRC and UKC for AD in childhood in order to generate an international consensus for clinical trials.

Atopic dermatitis is the most common chronic skin disease in childhood.1 Although itching and chronic/relapsing course are the predominant features, it has a varied range of manifestations as presentation, distribution and severity.2 There is not a diagnostic laboratory marker or diagnostic criteria accepted as the gold standard. This may cause over/under diagnosis and prevent eligible therapy.

The Hanifin-Rajka criteria (HRC) are the first developed and most cited diagnostic criteria in studies.3,4 Since the 1980s, they had been used to bring uniformity to the diagnosis. The items of HRC defined by dermatologists empirically on “clinical experience” and consensus between experts, especially for use in hospital settings,4 but had only been validated in two studies.5,6 However, some of the items were found to be useless because of requiring invasive tests and being non-specific for AD by Williams et al.7 But HRC still remains an important tool particularly in cases of atypical presentation.4

The United Kingdom Working Party criteria (UKC) were defined as a refinement of the original HRC in 1994 to be easier to use and better applicable for population-based studies.7,8 They are the only diagnostic criteria with several validation studies both in hospital and population-based settings.4,7,9,10 However, efficacy studies in children generated large variations in sensitivities (10–100%) and specificities (89–99%) in different age and ethnic groups.4,5,9,11 To date, HRC and UKC are the most validated and used criteria.2,8 In this study, we aimed to compare the diagnostic efficacy of HRC and UKC in outpatient clinics for children with AD.

MethodsPatientsChildren diagnosed with AD for the first time in the pediatric allergy clinic of a tertiary care hospital from January 2013 to July 2015 were enrolled consecutively in the study as the patient group. The children referred to the dermatology clinic of our hospital with skin problems other than AD were included as the control group. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Board (08.05.2012, 2012-026). Informed consent was received from the participants and their caregivers.

Clinical evaluationAll of the participants were evaluated by the same pediatric allergy specialists before treatment. The HRC and UKC were compared with the final dermatological diagnosis given to the patient by the pediatric allergists (AA, EC). Final diagnosis was decided by the consensus of the pediatric allergist writers (AA, EC, EDM, EV, CNK) and accepted as the reference method for the study. The dermatologic diseases in the control group were similar to those in the literature such as verrucosis, impetigo, seborrheic dermatitis, pityriasis versicolor, and chronic fungal skin infections.5,12 The medical and family histories were obtained from the caregivers. Family history of atopy was defined as having at least one parent with asthma and/or allergic rhinitis diagnosed by a physician.

Evaluation of diagnostic criteriaBoth patients and controls were investigated with both HRC and UKC. HRC are based on the presence of three of four major criteria and at least three of the minor criteria.3 In the original version, there are 23 minor items and six additional related items.13 “Delayed blanch” — one of the minor items — was not included because it was difficult to evaluate objectively and also it was agreed to have no diagnostic value in the studies.13,14 Additionally, “keratoconus” and “anterior subcapsular cataract” were not evaluated because of the need for special ophthalmological examination and were also reported to be non-specific.11

“Itchy skin condition in the preceding 12 months” was the only major item for UKC. Additionally, at least three of four minor features has to be fulfilled (Table 3).7 The only criterion with an objective sign is visible dermatitis in UKC.4 “Visible flexural dermatitis” and “history of flexural dermatitis” were evaluated for children older than 18 months. For those younger than 18 months, the involvement of cheek and extensor sites of extremities is also accepted as in the literature.15 When compared to HRC, “itchy skin condition”, “family or personal history of atopy” and “typical distribution” (also “history of flexural dermatitis”) were similar items for both criteria. Whereas, “early onset” that is one of the minor items of HRC is defined as a major item in UKC.4,8

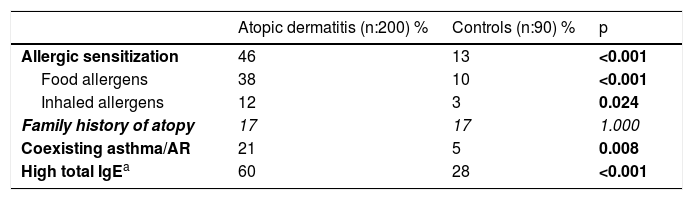

Frequency of allergic sensitization, coexisting asthma/AR and family history of atopy in AD and control groups (the statistically non-significant values are shown in italics).

| Atopic dermatitis (n:200) % | Controls (n:90) % | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allergic sensitization | 46 | 13 | <0.001 |

| Food allergens | 38 | 10 | <0.001 |

| Inhaled allergens | 12 | 3 | 0.024 |

| Family history of atopy | 17 | 17 | 1.000 |

| Coexisting asthma/AR | 21 | 5 | 0.008 |

| High total IgEa | 60 | 28 | <0.001 |

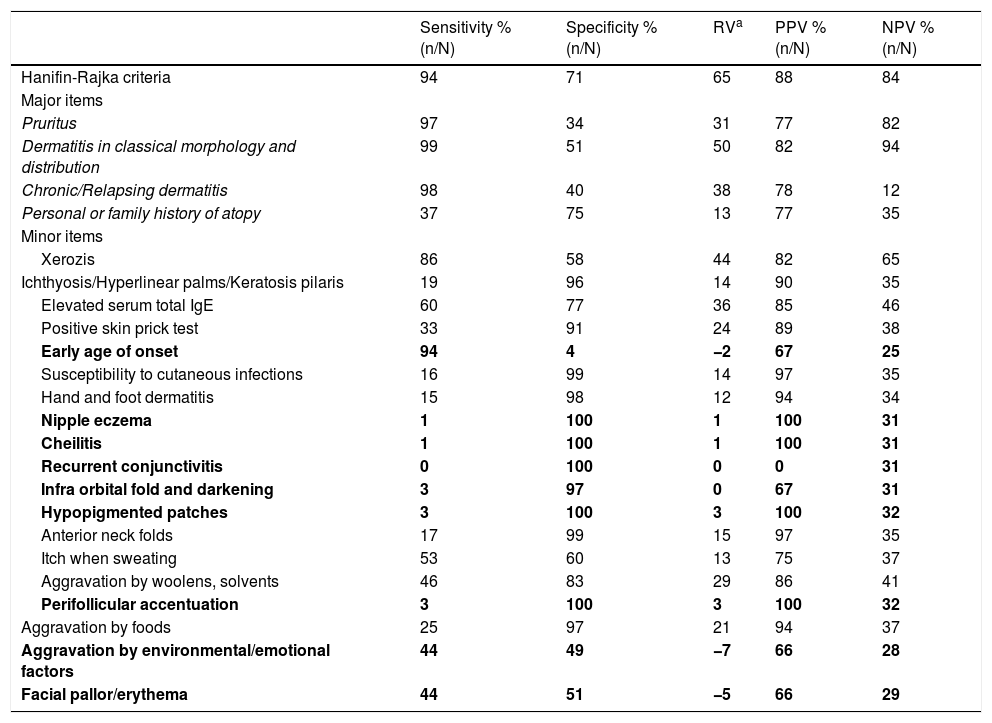

The sensitivity, specificity, relative value (RV), positive (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of Hanifin-Rajka’s major and minor items.

| Sensitivity % (n/N) | Specificity % (n/N) | RVa | PPV % (n/N) | NPV % (n/N) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hanifin-Rajka criteria | 94 | 71 | 65 | 88 | 84 |

| Major items | |||||

| Pruritus | 97 | 34 | 31 | 77 | 82 |

| Dermatitis in classical morphology and distribution | 99 | 51 | 50 | 82 | 94 |

| Chronic/Relapsing dermatitis | 98 | 40 | 38 | 78 | 12 |

| Personal or family history of atopy | 37 | 75 | 13 | 77 | 35 |

| Minor items | |||||

| Xerozis | 86 | 58 | 44 | 82 | 65 |

| Ichthyosis/Hyperlinear palms/Keratosis pilaris | 19 | 96 | 14 | 90 | 35 |

| Elevated serum total IgE | 60 | 77 | 36 | 85 | 46 |

| Positive skin prick test | 33 | 91 | 24 | 89 | 38 |

| Early age of onset | 94 | 4 | −2 | 67 | 25 |

| Susceptibility to cutaneous infections | 16 | 99 | 14 | 97 | 35 |

| Hand and foot dermatitis | 15 | 98 | 12 | 94 | 34 |

| Nipple eczema | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 31 |

| Cheilitis | 1 | 100 | 1 | 100 | 31 |

| Recurrent conjunctivitis | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 31 |

| Infra orbital fold and darkening | 3 | 97 | 0 | 67 | 31 |

| Hypopigmented patches | 3 | 100 | 3 | 100 | 32 |

| Anterior neck folds | 17 | 99 | 15 | 97 | 35 |

| Itch when sweating | 53 | 60 | 13 | 75 | 37 |

| Aggravation by woolens, solvents | 46 | 83 | 29 | 86 | 41 |

| Perifollicular accentuation | 3 | 100 | 3 | 100 | 32 |

| Aggravation by foods | 25 | 97 | 21 | 94 | 37 |

| Aggravation by environmental/emotional factors | 44 | 49 | −7 | 66 | 28 |

| Facial pallor/erythema | 44 | 51 | −5 | 66 | 29 |

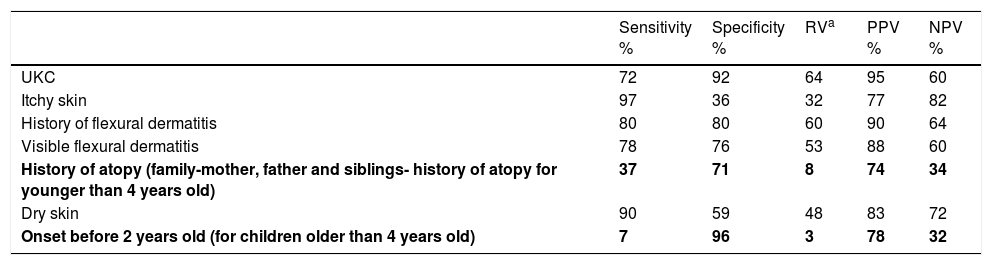

The sensitivity, specificity, relative value (RV), positive (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of UKC (items with similar frequency for AD and control groups are shown in bold).

| Sensitivity % | Specificity % | RVa | PPV % | NPV % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UKC | 72 | 92 | 64 | 95 | 60 |

| Itchy skin | 97 | 36 | 32 | 77 | 82 |

| History of flexural dermatitis | 80 | 80 | 60 | 90 | 64 |

| Visible flexural dermatitis | 78 | 76 | 53 | 88 | 60 |

| History of atopy (family-mother, father and siblings- history of atopy for younger than 4 years old) | 37 | 71 | 8 | 74 | 34 |

| Dry skin | 90 | 59 | 48 | 83 | 72 |

| Onset before 2 years old (for children older than 4 years old) | 7 | 96 | 3 | 78 | 32 |

UKC United Kingdom Criteria.

Skin prick tests (SPT) were performed on the volar aspect of the forearm or the back of the patients. Foods (cow’s milk, hen’s egg, wheat, peanut, soy and fish) and common inhaled allergens (house dust mites, cockroach, animal danders, fungi and mixed grass pollens) were used as allergens.16,17 All SPT were performed using commercial extracts (Laboratoire Stallergenes, France). Temoline was used as negative control and histamine (10mg/ml) as positive control. Reaction was evaluated 15–20min after allergens were applied. The wheal diameter of a positive test was at least 3mm greater than that of the negative control.17

Laboratory evaluationTotal immunoglobulin E (tIgE) was measured for all participants with nephelometric method (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Products, Marburg, Germany). If tIgE was above the cut-off levels according to age,18 it was defined as “high” tIgE.

Specific IgE (spIgE) was performed as a screening tool for foods (fx5) and common inhaled allergens such as mites and animal danders if no sensitization was detected with SPT. It was measured with fluorescence enzyme immunoassay (FEIA) as proposed by the manufacturer (UniCAP, Phadia; Uppsala, Sweden). SpIgE tests were defined as positive if the results were above the detection limit (>0.35 kU/L).

Severity assessment of eczemaObjective SCORAD index (oSCORAD) was used to determine severity of AD. It consists of A and B scores. The A score is the definition and grading of intensity items. Six items are selected: erythema, edema/papules, oozing/crusts, excoriations, lichenification, and dryness. Each item may be graded from 0 to 3 (0=absent, 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe), and thus, the A score ranges from 0 to 18. The B score grades the extent of eczema and is indicated as percentage of the patient’s total body surface. The total final score is calculated as A/5+7B/2. It ranges from 0 to 100. Patients with a total score under 15 were classified as mild, 15–40as moderate, and over 40 as severe AD.19

Statistical analysisThe definitions were provided as number and percentage for discrete variables, and as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. Chi-square test was used for discrete variables of two unrelated groups, and Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables not distributed normally. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. Kappa test was used to evaluate the agreement between the diagnostic criteria. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software was used for the statistical analysis of the obtained data.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were assessed for the criteria — HRC, UKC- and the items of the criteria individually. Clinical diagnosis was determined as the reference diagnostic method. Relative value (RV) was calculated by subtracting 100 from the sum of sensitivity and specificity.20 Accuracy rate of the criteria (true positive+true negative/all participants) according to the clinical diagnosis was also assessed.

ResultsCharacteristics of the study populationThe AD group and the control group consisted of 200 and 90 children, respectively. Sixty-eight percent (136/200) of the AD group were male. Median (IQR) age of AD patients was 13.5 (7–36) months, ranging between two months and 17.3 years-old. Age and sex distribution of the groups were similar (p=0.11 and p=0.34, respectively). The diagnosis of the controls included xeroderma, insect bite, keratosis pilaris, contact dermatitis, chronic urticaria, photosensitive dermatitis, miliaria, impetigo, seborrheic dermatitis, chronic fungal skin infections, verrucosis, infantile acne and pityriasis versicolor. One hundred and twenty six patients in the AD group (63%) were younger than 24 months. For the participants younger than 24 months of age, sex distribution was similar between AD and control groups (p=0.34). Sixty-five percent (n:130) of the patients had their first AD complaints before the age of six months.

All the participants underwent SPT. Seventy-nine percent of AD patients (158/200) and 78% of controls (70/90) were also evaluated with specific IgE tests (Table 1). Median of the oSCORAD index of the patients was 21.2, ranging between four and 48.7. Severity score was similar between the positive and negative groups for HRC and UKC (p=0.37 and 0.23, respectively). There were no differences between criteria for the patients with severe AD (oSCORAD higher than 40).

Evaluation of Hanifin-Rajka criteriaNinety-four percent (188/200) of the patients with clinical diagnosis of AD and 29% (26/90) of the control group fulfilled HRC. All of the major items were significantly more prevalent in the AD group than those in the control group (p<0.01). “Dermatitis in classical morphology and distribution” was the major item with the highest sensitivity, RV, PPV and NPV (Table 2).

The minor items with similar prevalence for AD and control groups were “early age of onset”; “nipple eczema”; “cheilitis”; “recurrent conjunctivitis”; “infraorbital fold and darkening”; “hypopigmented patches”; “perifollicular accentuation”; “aggravation by environmental/emotional factors”; and “facial pallor/erythema”(p=0.59, 0.34, 0.34, 1.00, 0.88, 0.10, 0.10, 0.26, 0.39, respectively).

Evaluation of United-Kingdom Working Party criteria (UKC)Seventy-two percent (144/200) of the patients with AD and 88% (79/90) of the control group fulfilled the UKC. The items of “history of atopy” and “onset before 2 years old” in AD group could not differentiate AD patients from controls (p=0.20, 0.40, respectively). “History of flexural dermatitis” and “visible flexural dermatitis” were the items with the highest RV and PPV (Table 3).

Comparison of the criteriaThe HRC were superior to the UKC for sensitivity, negative predictive value, kappa and accuracy rate (94% vs. 72%, 84% vs. 60%, 0.68 vs. 0.56, and 87 vs. 78, respectively). On the other hand, specificity and positive predictive value of the UKC were better than those of HRC (92% vs. 71% and 95% vs. 88%, respectively, Table 4). Regarding the consistency of the HRC and UKC, the UKC defined 74% of AD patients that were accurately diagnosed by the HRC. However, the UKC selected 98% of the controls who were correctly rejected to be AD by the HRC.

DiscussionThe challenge for establishing diagnostic criteria for AD is going on. There have been several diagnostic criteria developed over time. One of the main problems is the need for consistent description of the patients, which is essential for comparability and interpretability of studies and avoiding misdiagnosis of patients8 In our study, the clinical efficacy and accuracy of HRC and UKC were compared with the clinical diagnosis. The study population was composed of children with AD and controls with similar age and sex. As a result, the HRC had the highest accuracy and compatibility with clinical diagnosis.

As in most of the literature about diagnostic criteria, clinical diagnosis by a group of experts was determined as the gold standard in our study.2,4 De et al. and Shultz Larsen et al. had investigated the efficacy of HRC with the same study plan — using the clinical diagnosis as reference standard- and a pediatric patient population.5,12 The sensitivity of HRC in our study (94%) was similar to those studies, in which the sensitivities were 88% and 96%, respectively. However, the specificities of their studies (94% and 78%, respectively) were higher than in our study (71%).5,12 This might be due to the younger age of our study population than the participants in those studies (4.8 and 7 years old, respectively).5,12 Accordingly, the accuracy rate (87%) and compatibility (kappa value [KV]) (0.68) of our study was similar to the study of Johnke et al. in which they compared visible eczema with HRC in children younger than two years old and found an accuracy rate of 93% and a KV of 0.62.11

Similar to the literature, “dermatitis in classical morphology and distribution” and “chronic/relapsing dermatitis” were the major items with the highest sensitivity and RV for HRC.5 Nevertheless, the specificity of all major items was lower than it was in the literature.5 Also, Kanwar et al. argued the specificity of major items of HRC for the diagnosis of AD.21–23 They noted that “pruritus” may change from person to person and may be found in many other dermatologic diseases such as urticaria, contact dermatitis or seborrheic dermatitis which are in the differential diagnosis of AD. This is also right for the item of “chronic/relapsing dermatitis”.21 Prevalence of allergic diseases has been increasing gradually, so “family history of atopy” may not be specific for AD.21 Besides this, some of the children with AD do not have atopic features in the early years of life. This could be attributed to the fact that AD is the initial step of the “allergic march” and often develops during the first months of life.1,15 Consequently, it could be noted that major items are needed, but are not enough to diagnose AD without minor items.

There are more studies about minor items of the HRC in the literature. Several studies demonstrated that there was no clinical significance of “nipple eczema”, “cheilitis”, “recurrent conjunctivitis”, “perifollicular accentuation”, “ichthyosis”, “hypopigmented patches”, and “aggravation by foods” in discriminating children with AD.13,22,23 Similarly, our results demonstrated that those minor items had no clinical significance except “ichthyosis” and “aggravation by foods”. Moreover, Rudzki et al. demonstrated that “infraorbial folds” and “anterior neck folds” were important in diagnosing AD.24 We also found “anterior neck folds” to be significantly more prevalent in the AD group, but not “infraorbital folds”. In addition to the above-mentioned minor items, De et al. demonstrated that the frequency of “facial pallor/erythema”, “aggravation by emotional factors”, “susceptibility to cutaneous infections” and “hand and foot dermatitis” had no significance for discriminating AD in young children.5 According to our study, “susceptibility to cutaneous infections” and “hand and foot dermatitis” were more frequent in AD group, but their RV was low. Frequency of “early age of onset” was not different for the groups in our study, either. The minor items with the highest RV in our study were “xerozis”, “elevated serum total IgE” and “aggravation by woolens and solvents” (Table 2).

In their studies, Nagaraja et al. and Rudzki et al. argued that the specificity and prevalence of both major and minor items of HRC could be affected by the age of the patients.24,25 The age of our patients was younger than those in the studies discussed above. Accordingly, different age groups in different studies may be a factor of different frequency, sensitivity and specificity values of HRC among studies. Similarly, some researchers claimed that minor items might change by gender, race or ethnic origin.13,23

The HRC had been point of origin and reference criteria for most of the other diagnostic criteria such as the UKC.2 The researchers tried to define the most practical and reliable criteria for their study population and age group. One of the reasons for the need for a new set of diagnostic criteria is that some of the items of the HRC are difficult to evaluate objectively and so may vary in results from physician to physician for the same patient. Besides this, the application of the HRC requires invasive tests and time.11,13,14 In the literature, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of the UKC showed a wide variety in studies with children of different age groups.8,9,20 De et al. highlighted that the statistical values of the UKC were lower in children younger than 12 months old, when compared with their whole study population whose median age was 4.8 years.5 Herein, we have demonstrated similar results with the aforementioned study. Similarly, the UKC had lower sensitivity and specificity regarding the patients younger than 12 months than the rest of the cases in our study (data not shown). In the study of Johnke et al. evaluating visible eczema in children younger than two years old, accuracy rate and kappa value were 93% and 0.580 for UKC, respectively.11 The Kappa value was comparable with our results (0.56), but the accuracy rate in our study was much lower (78%). Hereby, the younger the age is, the lower the diagnostic efficacy of the UKC seems to be.

The most valuable items of the UKC in the previous studies were “visible flexural dermatitis”, “history of flexural dermatitis”, “itchy skin” and “dry skin”, as they were in our study.5,9,20 All of these items were altogether reflecting the items of “dermatitis in classical morphology and distribution”, “pruritus” and “xerozis” in the HRC. “History of atopy” and “onset before two years old–for >4 years old-“were the items with the lowest sensitivity and NPV, as they were in the literature.5 As regards “personal and family history of atopy” and “early age of onset” in the HRC, these items were not suitable to distinguish AD in younger children. As a result, the items of the UKC with higher efficacy to diagnose AD corresponded to “dermatitis in classical morphology and distribution”, “pruritus” and “xerosis” items of HRC.

The UKC is more compatible with the HRC for determining controls rather than diagnosing AD patients. This could be interpreted as the UKC being more appropriate for population-based studies. It supports the fact that the UKC were developed as a refinement of the HRC to be easier to use and suitable for population-based studies.8

The limitation of our study is that clinical diagnosis by the consensus of the panel of pediatric allergists is accepted as the reference method. This might have led to overestimation of sensitivity and specificity.26 But, there is no other choice than assessing the clinical diagnosis as the gold standard at the moment. This problem could be partly solved with a panel of experts instead of evaluating the patients by only one physician.

While the need for establishing the ideal diagnostic criteria is continuing, the HRC seems to discriminate young children with AD in hospital settings better than the UKC. The HRC were the most commonly used in all ages, regions and interventions up to date.8 In order to contribute to the attempts of generating an international consensus for diagnosing AD, the HRC might be recommended to be kept in mind particularly for future studies with young children.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest related to the manuscript.