Quality of life, which is impaired in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), is influenced by comorbid mental disorders. Headaches could be another comorbid mental disorder that affects quality of life in children with CSU.

ObjectivesTo investigate the effect of headaches on urticaria symptoms, disease activity and quality of life in children with CSU.

MethodsA total of 83 patients with CSU were enrolled in the study and were separated into two groups as those with or without headache. Demographic and clinical characteristics were studied with the Urticaria Activity Score (UAS7), Urticaria Control test (UCT) and Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire (CU-Q2QoL). The headache questionnaire designed according to the Department of International Classification of Headache Disorders, second edition (ICHD-II) was used and VAS (Visual Analogue Scale) and NRS (Numerical Rating Scale) were used to assess the pain measurement. In patients diagnosed with migraine, the paediatric Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (PedMIDAS) was applied.

ResultsCU-QoL total scores were significantly higher in patients with CSU with headache than in those without headache (p=0.015). In the five domains of CU-QoL, impact of daily life activities domain and sleep problems domain had higher scores in CSU with headache (p=0.008, 0.028, respectively). There was no significant relationship between UCT, UAS and CU-QoL and headache severity (p<0.05). No differences were found between the groups in respect of duration of urticaria, UAS7 and UCT.

ConclusionHeadache may be an important factor that affects and impairs quality of life in children with chronic urticaria.

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), which is defined as the persistence of urticaria for more than six weeks, is rare but has a significant impact on quality of life due to unknown aetiology.1 There are little data on the prevalence and aetiology of CSU in children.2,3 Previous studies have reported that CSU is associated with infections, autoimmunity, thyroid disease, and pseudo-allergies to a food.4–7

Headache represents the most common neurological disorder in the paediatric population and is the main source affecting social life.8 Headaches and allergies are both common in children and teenagers and they can cause significant distress and disability for young patients and their families.9 Several studies have documented the association between migraine and various comorbidities or psychosocial factors. In particular, many studies have reported associations between migraine and atopic disease such as food allergy, asthma, or allergic rhinitis.10 Little is known about the relationship between migraine and CSU.

Tension-type headache (TTH) is the most common type of headache experienced in the general population. It seems to be most common when individuals are under significant stress due to emotional distress or poor sleep.11

Several reports have suggested that CSU may emerge through interactions between the nervous and immune systems.12 Previous studies have reported a high prevalence of comorbidity between psychological factors and CSU.13 Levels of emotional distress have been seen to be significantly higher and generally increased in patients with CSU with mental disorders.14

Quality of life, which is impaired in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU), is influenced by comorbid mental disorders.15 Data about the aetiology of CSU in the paediatric group are limited and based upon studies of the general adult population.16,17 Headaches could be another comorbid mental disorder that affects quality of life in children with CSU.

Due to the association between allergy and migraine, and similar psychological factors affecting both CSU and TTH, it can be considered that headache may trigger hives by causing stress and consequently affect the quality of life in children with CSU.

The aim of the present study was to determine the effect of headaches on urticaria symptoms, disease activity and quality of life in children with CSU.

Materials and methodsStudy populationThis cross-sectional study was conducted in the Paediatric Allergy and Neurology Outpatient Clinics of our hospital between October 2017 and June 2018. Approval for the study was granted by the hospital Ethics Committee, and written informed consent was given by the parents or legal guardians of the patients. The study population comprised both male and female patients aged between 7 and 17 years, clinically diagnosed with chronic urticaria, characterised by the occurrence of erythematous, papulous, prurigous lesions for a period of over six weeks. Patients diagnosed with acute urticaria and physical urticaria, patients unable to understand the study items, and patients with psychiatric comorbidities were excluded from the study.

Assessment of disease activityDisease activity was evaluated by the same paediatric allergist using the urticaria activity score (UAS7) as the sum of the daily UASs for seven consecutive days in patients, according to the EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/WAO Guidelines.18

Assessment of Chronic Urticaria Control test (UCT)The urticaria control test was evaluated using the scoring system described by Weller et al.19 The UCT is the first valid and reliable tool to assess disease control in patients with chronic urticaria (spontaneous and inducible). Each UCT item has five response options (scored with 0–4 points). Low points indicate high disease activity and low disease control. In the UCT validation phase, the UCT score is calculated by adding all four individual item scores. Accordingly, the minimum and maximum UCT scores are 0 and 16, with 16 points indicating complete disease control.

Assessment of quality of life in CU patientsThe effect of CU on QoL was evaluated using the Turkish version of the Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire (CU-Q2QoL).20 That questionnaire contains 23 items grouped into six QoL categories associated with the disease: itching (two items), swelling (two items), activities (six items), sleep (five items), limitations (three items), and appearance (five items). The responses are rated on a five-point scale, from 0 to 4 points, with a higher score indicating a greater influence of CU on reduced QoL.

Headache questionnaireThe headache questionnaire was applied in two stages. First individuals were asked if they had recurrent headaches. A recurrent headache was defined as a headache (with at least two occurrences during life) in the absence of an underlying cause (infection, trauma, etc.). The second section was completed by respondents who gave a positive answer to the first question. This section consisted of items designed according to the Department of International Classification of Headache Disorders, second edition (ICHD-II). This questionnaire consisted of eight questions about the headache episodes: frequency, location, duration, pulsating quality, intensity (moderate or severe), the occurrence of nausea, vomiting, photophobia and phonophobia, and aggravation with routine physical activity. In addition, questions were asked about the pain history, pain intensity (on a 10-point pain scale), and whether he or she had been previously diagnosed with migraine. In patients diagnosed with migraine, the paediatric Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (PedMIDAS) was applied.21 All the forms that were applied are included in Appendix A. The answers were evaluated according to the criteria in the ICHD-II and the patients who were assumed to have headaches and migraine were evaluated by a child neurologist, and a headache classification was made. The headaches were classified as migraine, tension-type headache (TTH) and other headaches. The PedMIDAS was calculated. For the PedMIDAS scoring, the verbatim Turkish version, with proven validity and reliability, was used (Appendix A).

Pain measuresTo evaluate the pain intensity in patients with headache, the VAS (Visual Analogue Scale) and NRS (Numerical Rating Scale) were applied. VAS is a psychometric response scale which can be used in questionnaires. It is a measurement instrument for characteristics or attitudes that cannot be directly measured. Participants specify their level of pain intensity by indicating a position along a continuous line between two end-points (0–10). The Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) is an 11-point scale from 0 to 10, where 0 indicates “no pain”, and 10 indicates the “worst imaginable pain”. Patients are instructed to choose a single number from the scale that best indicates their level of pain.22

Laboratory investigationsLaboratory investigations included complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), total IgE, C3 and C4 levels, free thyroxine and thyroid-stimulating hormone, thyroid autoantibodies (anti-thyroid peroxisomal antibody, anti-thyroglobulin antibody), anti-nuclear antibody, urine analysis and stool for parasites.

A skin test was performed with common aeroallergens and common food allergens as indicated by the history. Commercial allergen solutions manufactured by Allergopharma (Allergopharma, Reinbek, Germany) were used for skin tests. The allergens used included pollens (grass mixture, tree mixture), cereals, mould mixture, cat, dog, cockroach and house dust mites (HDM), Dermatophagides pteronyssinus, Dermatophagides farinae, and seven food allergens consisting of milk, egg white, egg yolk, peanut, wheat, sesame and cocoa. Saline and histamine were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. When the positive control oedema was >3mm and there was no reaction in the negative control, this was considered positive in the skin prick test. An autologous serum skin test (ASST) was performed using the method described by Sabroe et al.23

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences ver. 20.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were defined as mean±standard deviation for parametric tests, and as median and range (minimum–maximum) for non-parametric tests. The Chi-square test was used for the comparison of categorical variables. In the analysis of the difference between the values of two groups, the normality hypothesis was tested with the Shapiro–Wilk test. For parameters showing normal distribution, the Student's t-test was used and for those without normal distribution, the Mann–Whitney U-test was used. A value of p<0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

ResultsEvaluation was made of a total of 83 patients (43 boys and 40 girls [male: female ratio, 1.075]) with a mean age of 12.18±3.37 years (range, 7–17 years). When examined in each year group, 10 (12%) patients were 7 years old, eight (9.6%) were 8 years old, six (7.2%) were 9 years old, three (3.6%) were 10 years old, seven (8.4%) were 11 years old, eight (9.6%) were 12, 13 and 14 years old, six (7.2%) were 15 years old, nine (10.8%) were 16 years old, and 10 (12%) were 17 years old.

The mean ages of the CSU with headache and CSU without headache groups were 13.06±3.01 years and 12.12±3.34 years, respectively. No significant difference in age was determined between the two groups (p=0.264). Headache was more common in girls among children with urticaria and headache (n=13, 76.5% girls, n=4, 23.5% boys, p=0.009). Angioedema was observed in 55 (63%) of all the cases.

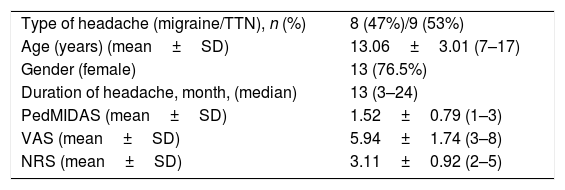

Of the 17 (20.5%) patients with CSU with headache, nine (53%) were tension-type headache and eight (47%) had migraine. The median duration of headache was 13 months (3–24). The median VAS value for the CSU with headache group was 5.94±1.74 (3–8), while the NMS values were 3.11±0.92 (2–5) and the PEDMIDAS values were 1.52±0.79 (1–3).

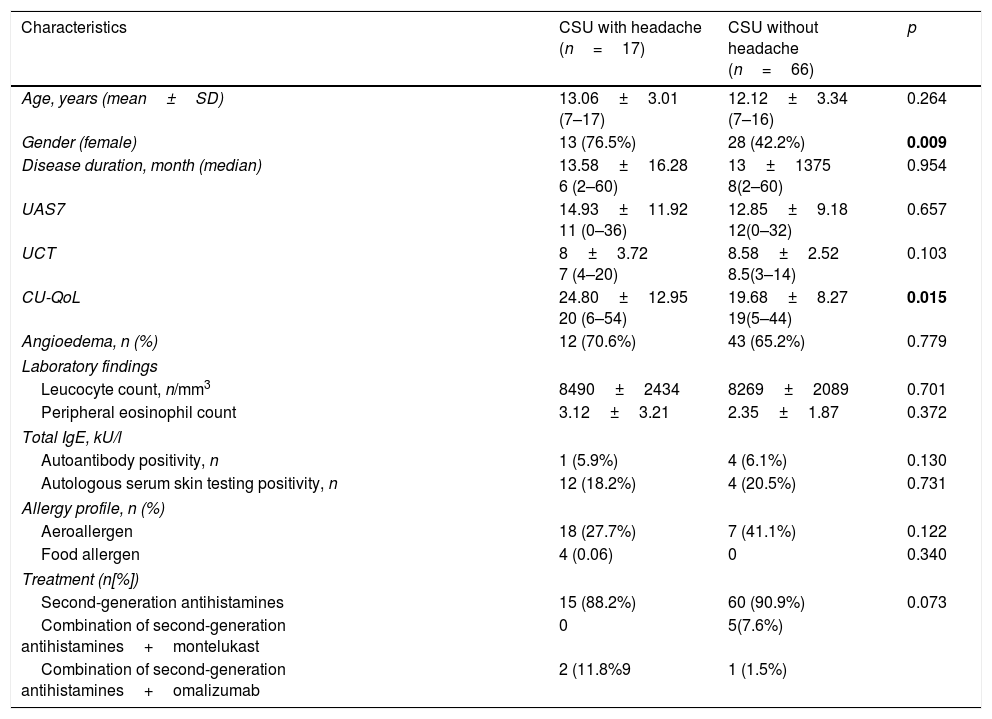

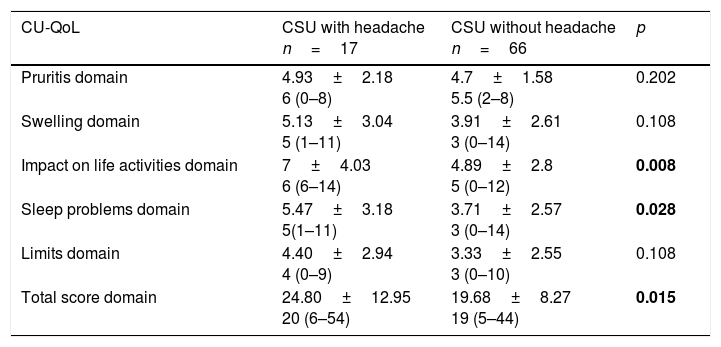

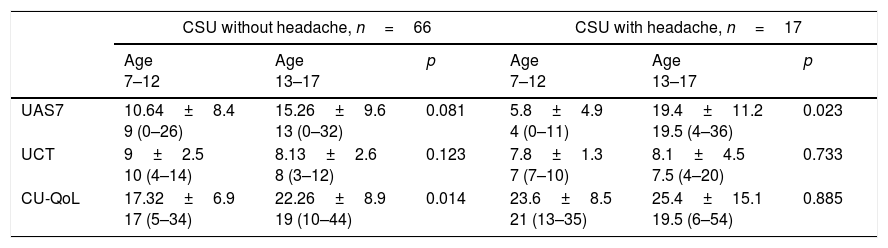

Comparison of the clinical and laboratory characteristics of the patients with CSU with headache and those without is shown in Table 1. CU-QoL total scores were significantly higher in patients with CSU with headache than in those without (p=0.015). In the five domains of CU-QoL, the impact of daily life activities domain and sleep problems domain had higher scores in CSU with headache (p=0.008, 0.028, respectively) (Tables 2 and 3). There was no significant relationship between UCT, UAS and CU-QoL and headache severity (p<0.05). There was no diffrences in terms of UAS7, UCT and CU-QoL according to ages (Table 4).

Comparison of clinical and laboratory characteristics between CSU patients with headache and without headache.

| Characteristics | CSU with headache (n=17) | CSU without headache (n=66) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 13.06±3.01 (7–17) | 12.12±3.34 (7–16) | 0.264 |

| Gender (female) | 13 (76.5%) | 28 (42.2%) | 0.009 |

| Disease duration, month (median) | 13.58±16.28 6 (2–60) | 13±1375 8(2–60) | 0.954 |

| UAS7 | 14.93±11.92 11 (0–36) | 12.85±9.18 12(0–32) | 0.657 |

| UCT | 8±3.72 7 (4–20) | 8.58±2.52 8.5(3–14) | 0.103 |

| CU-QoL | 24.80±12.95 20 (6–54) | 19.68±8.27 19(5–44) | 0.015 |

| Angioedema, n (%) | 12 (70.6%) | 43 (65.2%) | 0.779 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| Leucocyte count, n/mm3 | 8490±2434 | 8269±2089 | 0.701 |

| Peripheral eosinophil count | 3.12±3.21 | 2.35±1.87 | 0.372 |

| Total IgE, kU/l | |||

| Autoantibody positivity, n | 1 (5.9%) | 4 (6.1%) | 0.130 |

| Autologous serum skin testing positivity, n | 12 (18.2%) | 4 (20.5%) | 0.731 |

| Allergy profile, n (%) | |||

| Aeroallergen | 18 (27.7%) | 7 (41.1%) | 0.122 |

| Food allergen | 4 (0.06) | 0 | 0.340 |

| Treatment (n[%]) | |||

| Second-generation antihistamines | 15 (88.2%) | 60 (90.9%) | 0.073 |

| Combination of second-generation antihistamines+montelukast | 0 | 5(7.6%) | |

| Combination of second-generation antihistamines+omalizumab | 2 (11.8%9 | 1 (1.5%) | |

Bold value represents the statistically differences.

Results are expressed as n (%) or median [interquartile range], UAS7=the sum of the daily urticaria activity score over seven consecutive days, UCT: Urticaria control test, CU-QoL: Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire.

Characteristics of CSU patients with headache.

| Type of headache (migraine/TTN), n (%) | 8 (47%)/9 (53%) |

| Age (years) (mean±SD) | 13.06±3.01 (7–17) |

| Gender (female) | 13 (76.5%) |

| Duration of headache, month, (median) | 13 (3–24) |

| PedMIDAS (mean±SD) | 1.52±0.79 (1–3) |

| VAS (mean±SD) | 5.94±1.74 (3–8) |

| NRS (mean±SD) | 3.11±0.92 (2–5) |

TTN: tension-type headache; PedMIDAS: Paediatric Migraine Disability Assessment Scale; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale; NRS: Numerical Rating Scale.

Comparison of CU-QoL between CSU with headache and without headache.

| CU-QoL | CSU with headache n=17 | CSU without headache n=66 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pruritis domain | 4.93±2.18 6 (0–8) | 4.7±1.58 5.5 (2–8) | 0.202 |

| Swelling domain | 5.13±3.04 5 (1–11) | 3.91±2.61 3 (0–14) | 0.108 |

| Impact on life activities domain | 7±4.03 6 (6–14) | 4.89±2.8 5 (0–12) | 0.008 |

| Sleep problems domain | 5.47±3.18 5(1–11) | 3.71±2.57 3 (0–14) | 0.028 |

| Limits domain | 4.40±2.94 4 (0–9) | 3.33±2.55 3 (0–10) | 0.108 |

| Total score domain | 24.80±12.95 20 (6–54) | 19.68±8.27 19 (5–44) | 0.015 |

CU-QoL: Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire.

Comparison of the patients UAS7, UCT and, CU-QoL according to age.

| CSU without headache, n=66 | CSU with headache, n=17 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 7–12 | Age 13–17 | p | Age 7–12 | Age 13–17 | p | |

| UAS7 | 10.64±8.4 9 (0–26) | 15.26±9.6 13 (0–32) | 0.081 | 5.8±4.9 4 (0–11) | 19.4±11.2 19.5 (4–36) | 0.023 |

| UCT | 9±2.5 10 (4–14) | 8.13±2.6 8 (3–12) | 0.123 | 7.8±1.3 7 (7–10) | 8.1±4.5 7.5 (4–20) | 0.733 |

| CU-QoL | 17.32±6.9 17 (5–34) | 22.26±8.9 19 (10–44) | 0.014 | 23.6±8.5 21 (13–35) | 25.4±15.1 19.5 (6–54) | 0.885 |

UAS7: sum of the daily urticaria activity score over seven consecutive days, UCT: Urticaria control test, CU-QoL: Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire.

No difference was determined between the groups in respect of duration of urticaria, UAS7 and UCT. Among the patients with CSU, the aetiology was identified in eight patients (10%) as food allergy (n=4), and Hashimoto thyroiditis (n=4). These two groups had similar haematology profiles and allergy profiles (Table 1).

DiscussionChronic urticaria is a frequently disabling disease with a negative influence on the quality of life. In the current study, higher scores were determined in CU-QoL for patients with headache. Moreover, the sleep and daily activities were also impaired in children with headache. These results suggest that headache may be an important factor that affects and impairs quality of life in children with chronic urticaria. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to determine the effect of headache on urticaria disease activity and quality of life in children.

Quality of life is markedly reduced in CU patients.15–17 Social functioning and emotions have been reported to be the areas of QoL most affected in CU patients. Psychiatric comorbidities significantly increase QoL impairment and most patients believe that their illnesses are due to stress.24

Several studies have reported that adults and children with CSU frequently exhibit mental disorders and emotional problems.25 Depression, anxiety and phobias are more common in children with urticaria. Sleep disorders such as insomnia, fatigue and drowsiness due to pruritis or side effects from antihistamines are frequently seen in patients with CU. Patients complain of recurrent pain syndromes, including tension headaches and fibromyalgia has been observed in an adult population with CU.26

Despite sharing similar triggers and comorbidities, there is limited knowledge to explain the relationship between chronic urticaria and headache.

In the current study, the aetiology and pathophysiology of both headache and CU were taken into consideration to explain the impairment of CU-QoL in children with headache.

These two chronic diseases both show a multifactorial aetiology including genetic factors, inflammatory mediators and common environmental factors. Currently, an integrated theory of migraine that involves both vascular and neuronal components is generally accepted. Neurogenic inflammation, a well-defined pathophysiological process, is characterised by the release of potent vasoactive neuropeptides, which lead to a cascade of inflammatory tissue responses including arteriolar vasodilation, plasma protein extravasation, and degranulation of mast cells in the peripheral target tissue. Neurogenic inflammatory processes have long been implicated as a possible mechanism in the pathophysiology of various diseases of the human nervous system, respiratory system and skin.27 Several studies have recently suggested that histamine may have a role in migraine pathogenesis and management. The histamine system interacts with multiple regions of the CNS and hypothetically, may modulate migraine response.28

The close relationship between stress and migraine attacks and significant psychiatric comorbidities associated with migraine has been well-documented.29

Several reports have suggested that CSU may emerge through interactions between the nervous and immune systems. Urticaria is a mast cell-mediated disease, although signals which lead to mast cell activation are variable and have not been clearly revealed.18 Mediators which are released from mast cells, such as histamine and platelet activating factor, lead to urticarial lesions through sensorial nerve activation, vasodilation and plasma extravasation.30 Patients with mastocytosis can display various disabling general and neuropsychological symptoms such as fatigue, headache, depression, dyspnoea, dyspepsia, nausea, and abdominal pain.31

Levels of emotional distress have been seen to be significantly higher and more commonly increased in patients with CSU with mental disorders.14 Symptoms result from mast cell activation, elicited through channels such as the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical axis, the sympathetic and adrenomedullary system and local skin nerve fibres.12 Stress-related mechanisms provide links to CSU, and acute stress results in cutaneous mast cell activation.

Özge et al. demonstrated that atopic disorders are more commonly reported in patients with migraine and a close correlation was seen between TTH and atopic disorders and psychiatric comorbid disorders of patients.32 The relationship between urticaria and headache has not been fully addressed in previous studies. In the present study, it was shown for the first time that the presence of headache increased the impairment of CU-QoL in children with CSU. Although headaches in children with CSU are debilitating in respect of sleep, daily activities and total CUQoL, no difference was determined in the UCT scores and UAS7 according to headache severity.

The main limitation of this study is that the results are based on a relatively small sample (n=83). There is a need for further, more extensive studies with larger samples to confirm these findings. The effects of urticaria and its treatment on many aspects of everyday life of adults are now being assessed. Although specially modified questionnaires were available for the assessment of the effects of allergic rhinitis in children, there were no reports of the modified versions of them to be used to assess the quality of life in childhood urticaria.33 Because the UCT and CU-Q2oL questionnaires were not fully validated for children, we modified the adult questionnaires. The original CU-Q2oL was translated into Turkish by Kocatürk et al., and the Turkish version was validated to be used with the urticaria in general population.20 So we picked random questions which were appropriate for us from the quality of life questionnaire recommended in adults. Because we did not have a quality of life questionnaire validated for chronic urticaria in children and we asked them in Turkish.

In conclusion, chronic urticaria seriously compromises the quality of life of children, and the results of this study showed that headache could also cause a significant reduction in the patient's quality of life. These findings suggest that when evaluating quality of life in chronic urticaria, attention should be paid to the presence of headache. Further studies are needed to better clarify the links between headache and CSU in children, adolescents and adults.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Antalya Training and Research Hospital.