The aim of the present study was to evaluate the knowledge, attitude and adherence to asthma management recommendations during pregnancy of Spanish health care professionals.

MethodsA multiple choice survey with 14 questions was designed. Items assessed opinion about asthma guidelines and attitudes towards treatment, spirometry, specific immunotherapy and labour in pregnant asthmatic patients. Test completion was voluntary, individual, and anonymous.

ResultsA total of 1000 questionnaires were fulfilled: respiratory medicine specialists (19.8%); allergy specialists (17.2%); primary care physicians (46.1%); and gynaecologists/obstetricians (16.9%). Guidelines were considered useful by 96.5% although 64% admitted that they followed them seldom or never. Most physicians (55.9%) answered that they would maintain asthma therapy in clinically stable patients. Almost 30% of physicians would not perform spirometry in pregnant asthma patients. 19% declared they would interrupt specific immunotherapy which had proven safe and effective. Univariate analysis revealed low adherence to be associated with the following variables: age, primary care or gynaecology/obstetrician specialisation, number of asthmatics attended per month, and declared use of guidelines for pregnant asthmatic patients. Multivariate analysis showed that being a primary care physician and a gynaecologist/obstetrician, attending a low number of asthma patients per month, and poor use of spirometry during pregnancy are associated to low adherence to asthma guidelines.

ConclusionEven though the majority of Spanish physicians surveyed seem to consider guidelines useful, their adherence to those is very low if translated to managing pregnant asthmatic patients. Educational strategies seem unavoidable and should be targetted mainly to primary care and gynaecology/obstetrician physicians.

Asthma is probably the most frequent co-morbidity in pregnancy.1 Maternal asthma is associated with increased risk of infant death, preeclampsia, premature birth and low birth weight. These risks are linked to asthma control. More severe asthma increases risk whilst better-controlled asthma is tied to decreased risks.2 During pregnancy, exacerbations of asthma requiring medical intervention occur in about 20% of women, with approximately 6% being admitted to hospital. The major triggers are viral infection and non-adherence to inhaled corticosteroid medication.3 Inhaled corticosteroid use may reduce the risk of exacerbations during pregnancy.4 The prophylactic use of inhaled corticosteroids continues to be low in asthma,5 and at least 40% of patients are prescribed only rescue medication.6 The guidelines emphasise that controlling asthma during pregnancy is important for the health and well being of the mother as well as the foetus.4,7 Managing asthma during pregnancy is unique because the effects of both the illness and the treatment on the developing foetus and the patient must be considered.8 Guidelines are of undoubted scientific value because they encourage convergence of terminology, diagnosis and treatment. Yet treatment still seems to be approached without consensus in daily practice even though many guidelines and recommendations are available. Furthermore, the adherence to those guidelines is very low even though the majority of Spanish healthcare professionals surveyed in a recent study seem to know about their existence.9

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the knowledge, attitude and adherence to asthma management recommendations during pregnancy of Spanish health care professionals.

Materials and methodsStudy design and populationThe study was designed to evaluate the level of knowledge, attitude and adherence to guidelines recommendations about asthma and pregnancy amongst Spanish health care professionals. A questionnaire consisting of 14 questions with closed multiple choice responses was developed to be answered by Spanish physicians belonging to primary care, gynaecology, respiratory specialists and allergy specialists. Participation in the survey was voluntary, individual, anonymous and immediate (not delayed), taking place at the beginning of sessions held during the scientific societies national meetings and conferences held in 2009.

QuestionnaireThe questionnaire was composed of 14 items with closed multiple choice responses. It could be answered very quickly in less than 5min; the first seven questions gathered information about the respondent's age, sex, speciality, geographic location and number of asthmatic and pregnant patients seen every month. Subsequent questions concerned the respondent's opinion about the usefulness and adherence to guidelines (item 8–9), attitude towards asthmatic maintenance therapy case based (item 10), use of spirometry during pregnancy (item 11), maintenance of specific immunotherapy during pregnancy (item 12), attitudes during labour in an asthmatic patient (item 13) and opinion about important policies/messages to be implemented or to be transmitted (item 14). An answer sheet that could be read optically was designed and responses were automatically entered into a database.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics were compiled for the entire population sample. Results for each item were expressed as percentages and compared between specialist groups by means of the χ2 test. Statistical significance was set at a value of P less than 0.05. Analyses were carried out with PASW Statistics 18 (formerly called SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

The level of adherence amongst the respondents in allergy medicine, respiratory medicine, primary care and gynaecology was established by combining responses to items 8 (level of adherence to guidelines); 10 (attitude treatment pregnant asthmatic patient); 11 (use of spirometry during pregnancy); and 12 (SIT during pregnancy). Responses to those four items were weighted to provide scores that ranged from 0 points (lowest) to 2 points (highest) to reflect lesser or greater adherence. The sum of points for all four items provided a score for a new variable termed “Recommendation adherence level” to allow stratification of the sample into three groups with similar numbers of respondents in each: physicians with poor adherence (total score <2 points), physicians with low adherence (3–4 points), and physicians with good adherence (≥5 points). Logistic regression was used to define a profile of the physician with poor guideline adherence. All the independent variables were included in the model whether or not they were significant in the bivariate analysis.

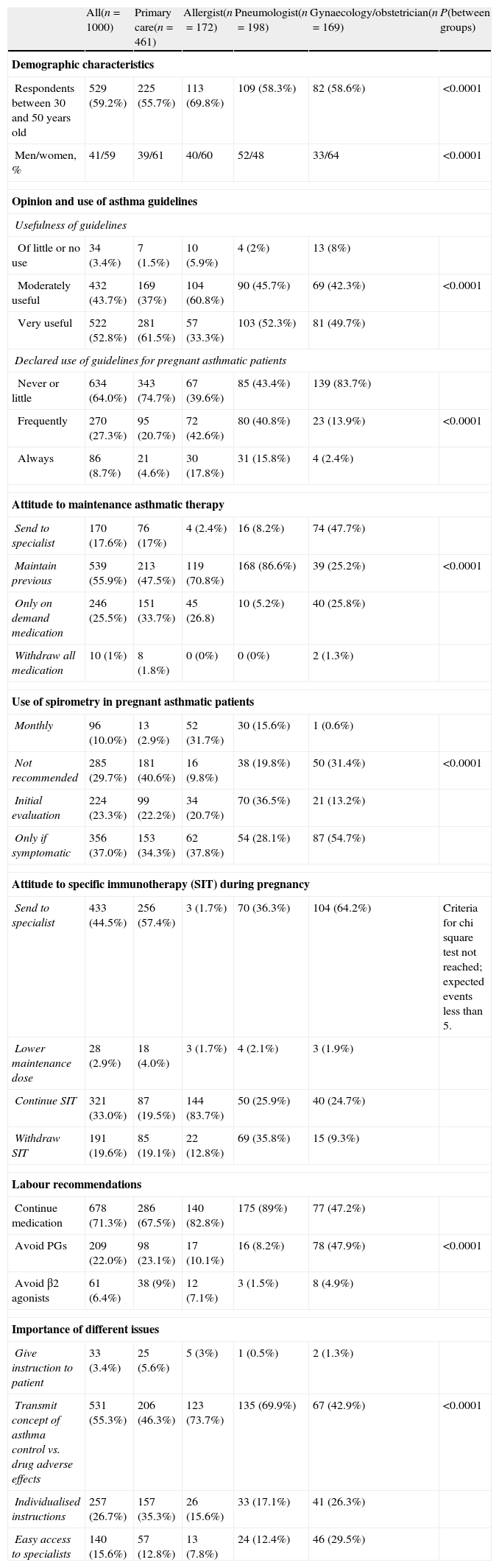

ResultsA total of 1000 questionnaires were returned from the above referred health care professionals; most were women (59%) with ages ranged from 30–59 years (84.3%). Table 1 displays the results for the whole sample and by specialities, demographic variables, and attitudes towards guidelines and its adherence.

Responses by specialities of total sample and demographic variables, and attitudes towards guidelines and its adherence.

| All(n=1000) | Primary care(n=461) | Allergist(n=172) | Pneumologist(n=198) | Gynaecology/obstetrician(n=169) | P(between groups) | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Respondents between 30 and 50 years old | 529 (59.2%) | 225 (55.7%) | 113 (69.8%) | 109 (58.3%) | 82 (58.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Men/women, % | 41/59 | 39/61 | 40/60 | 52/48 | 33/64 | <0.0001 |

| Opinion and use of asthma guidelines | ||||||

| Usefulness of guidelines | ||||||

| Of little or no use | 34 (3.4%) | 7 (1.5%) | 10 (5.9%) | 4 (2%) | 13 (8%) | |

| Moderately useful | 432 (43.7%) | 169 (37%) | 104 (60.8%) | 90 (45.7%) | 69 (42.3%) | <0.0001 |

| Very useful | 522 (52.8%) | 281 (61.5%) | 57 (33.3%) | 103 (52.3%) | 81 (49.7%) | |

| Declared use of guidelines for pregnant asthmatic patients | ||||||

| Never or little | 634 (64.0%) | 343 (74.7%) | 67 (39.6%) | 85 (43.4%) | 139 (83.7%) | |

| Frequently | 270 (27.3%) | 95 (20.7%) | 72 (42.6%) | 80 (40.8%) | 23 (13.9%) | <0.0001 |

| Always | 86 (8.7%) | 21 (4.6%) | 30 (17.8%) | 31 (15.8%) | 4 (2.4%) | |

| Attitude to maintenance asthmatic therapy | ||||||

| Send to specialist | 170 (17.6%) | 76 (17%) | 4 (2.4%) | 16 (8.2%) | 74 (47.7%) | |

| Maintain previous | 539 (55.9%) | 213 (47.5%) | 119 (70.8%) | 168 (86.6%) | 39 (25.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Only on demand medication | 246 (25.5%) | 151 (33.7%) | 45 (26.8) | 10 (5.2%) | 40 (25.8%) | |

| Withdraw all medication | 10 (1%) | 8 (1.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.3%) | |

| Use of spirometry in pregnant asthmatic patients | ||||||

| Monthly | 96 (10.0%) | 13 (2.9%) | 52 (31.7%) | 30 (15.6%) | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Not recommended | 285 (29.7%) | 181 (40.6%) | 16 (9.8%) | 38 (19.8%) | 50 (31.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Initial evaluation | 224 (23.3%) | 99 (22.2%) | 34 (20.7%) | 70 (36.5%) | 21 (13.2%) | |

| Only if symptomatic | 356 (37.0%) | 153 (34.3%) | 62 (37.8%) | 54 (28.1%) | 87 (54.7%) | |

| Attitude to specific immunotherapy (SIT) during pregnancy | ||||||

| Send to specialist | 433 (44.5%) | 256 (57.4%) | 3 (1.7%) | 70 (36.3%) | 104 (64.2%) | Criteria for chi square test not reached; expected events less than 5. |

| Lower maintenance dose | 28 (2.9%) | 18 (4.0%) | 3 (1.7%) | 4 (2.1%) | 3 (1.9%) | |

| Continue SIT | 321 (33.0%) | 87 (19.5%) | 144 (83.7%) | 50 (25.9%) | 40 (24.7%) | |

| Withdraw SIT | 191 (19.6%) | 85 (19.1%) | 22 (12.8%) | 69 (35.8%) | 15 (9.3%) | |

| Labour recommendations | ||||||

| Continue medication | 678 (71.3%) | 286 (67.5%) | 140 (82.8%) | 175 (89%) | 77 (47.2%) | |

| Avoid PGs | 209 (22.0%) | 98 (23.1%) | 17 (10.1%) | 16 (8.2%) | 78 (47.9%) | <0.0001 |

| Avoid β2 agonists | 61 (6.4%) | 38 (9%) | 12 (7.1%) | 3 (1.5%) | 8 (4.9%) | |

| Importance of different issues | ||||||

| Give instruction to patient | 33 (3.4%) | 25 (5.6%) | 5 (3%) | 1 (0.5%) | 2 (1.3%) | |

| Transmit concept of asthma control vs. drug adverse effects | 531 (55.3%) | 206 (46.3%) | 123 (73.7%) | 135 (69.9%) | 67 (42.9%) | <0.0001 |

| Individualised instructions | 257 (26.7%) | 157 (35.3%) | 26 (15.6%) | 33 (17.1%) | 41 (26.3%) | |

| Easy access to specialists | 140 (15.6%) | 57 (12.8%) | 13 (7.8%) | 24 (12.4%) | 46 (29.5%) | |

The distribution by speciality as follows: respiratory medicine specialists 19.8%, allergy specialists 17.2%, primary care physicians 46.1% and 16.9% from gynaecologists/obstetricians. Physicians from Madrid (187), Catalonia (214), Andalusia (114) and Valencia (131) returned most of the questionnaires (66.6%). Almost all respondents (96.6%) considered asthma guidelines to be useful or very useful, yet many declared they followed guidelines seldom or never (64%).

When asked about their attitude regarding maintenance asthmatic therapy during pregnancy if patient is clinically stable, 539 (55.9%) answered to keep previous treatment.

Between group comparison showed that this approach varied significantly. Pneumologists (86.6%) and allergists (70.8%) clearly had this opinion in contrast to primary care physicians (47.5%) or gynaecologists (25.2%). This difference was even more accentuated if questioned about the use of spirometry during pregnancy. So, 181 (40.6%) primary care physicians and 50 (31.4%) obstetricians considered it to be not recommended in opposition to allergists (9.8%) and pneumologists (19.8%). The attitude towards specific immunotherapy during pregnancy is also noteworthy. Health care professionals were asked what they would recommend to their patient on SIT on maintenance dose with good tolerance and clinical response if wanting to become pregnant. Most allergists (83.7%) replied to continue with SIT. Other health care professionals were more conservative, lowering the maintenance dose or withdrawing SIT. Attitudes during labour in an asthmatic patient and opinion about important policies/messages to be implemented or to be transmitted were also addressed. In this sense, most professionals (71.3%) recommended to continue with medication during labour and 531 (55.3%) considered it important to transmit the concept that asthma control is more beneficial than the potential drug adverse effects on the foetus.

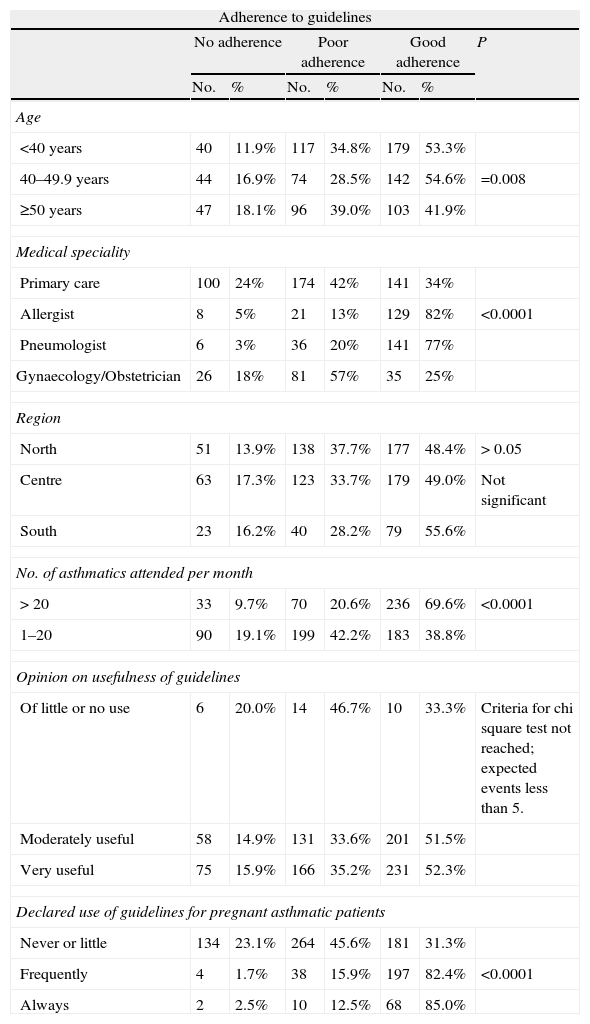

Table 2 shows the distribution of variables analysed for all physicians surveyed in all categories according to their adherence level (no, low, good). Univariate analysis revealed poor adherence to be associated with the following variables: age, primary care or gynaecology/obstetrician specialisation, number of asthmatics attended per month, and declared use of guidelines for pregnant asthmatic patients. The practicing region of the physician was not significantly associated to the adherence level to guidelines.

Degree of adherence to guidelines based on combined score for answers to items 8, 10, 11 and 12, according to medical speciality, demographic and geographic location, number of asthmatic patients attended and opinion and declared use of guidelines.

| Adherence to guidelines | |||||||

| No adherence | Poor adherence | Good adherence | P | ||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Age | |||||||

| <40 years | 40 | 11.9% | 117 | 34.8% | 179 | 53.3% | |

| 40–49.9 years | 44 | 16.9% | 74 | 28.5% | 142 | 54.6% | =0.008 |

| ≥50 years | 47 | 18.1% | 96 | 39.0% | 103 | 41.9% | |

| Medical speciality | |||||||

| Primary care | 100 | 24% | 174 | 42% | 141 | 34% | |

| Allergist | 8 | 5% | 21 | 13% | 129 | 82% | <0.0001 |

| Pneumologist | 6 | 3% | 36 | 20% | 141 | 77% | |

| Gynaecology/Obstetrician | 26 | 18% | 81 | 57% | 35 | 25% | |

| Region | |||||||

| North | 51 | 13.9% | 138 | 37.7% | 177 | 48.4% | > 0.05 |

| Centre | 63 | 17.3% | 123 | 33.7% | 179 | 49.0% | Not significant |

| South | 23 | 16.2% | 40 | 28.2% | 79 | 55.6% | |

| No. of asthmatics attended per month | |||||||

| > 20 | 33 | 9.7% | 70 | 20.6% | 236 | 69.6% | <0.0001 |

| 1–20 | 90 | 19.1% | 199 | 42.2% | 183 | 38.8% | |

| Opinion on usefulness of guidelines | |||||||

| Of little or no use | 6 | 20.0% | 14 | 46.7% | 10 | 33.3% | Criteria for chi square test not reached; expected events less than 5. |

| Moderately useful | 58 | 14.9% | 131 | 33.6% | 201 | 51.5% | |

| Very useful | 75 | 15.9% | 166 | 35.2% | 231 | 52.3% | |

| Declared use of guidelines for pregnant asthmatic patients | |||||||

| Never or little | 134 | 23.1% | 264 | 45.6% | 181 | 31.3% | |

| Frequently | 4 | 1.7% | 38 | 15.9% | 197 | 82.4% | <0.0001 |

| Always | 2 | 2.5% | 10 | 12.5% | 68 | 85.0% | |

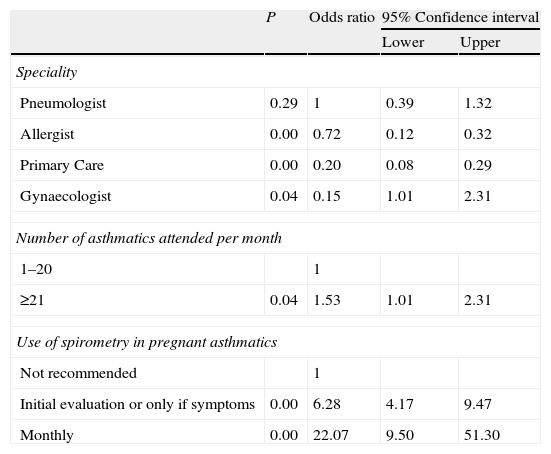

Multivariate analysis (Table 3) revealed that primary care and gynaecology/obstetrician physicians, lower number of asthma patients attended per month, and poor use of spirometry during pregnancy are associated to a low adherence to asthma guidelines.

Results of multivariate analysis to predict poor adherence to guidelines.

| P | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Speciality | ||||

| Pneumologist | 0.29 | 1 | 0.39 | 1.32 |

| Allergist | 0.00 | 0.72 | 0.12 | 0.32 |

| Primary Care | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.29 |

| Gynaecologist | 0.04 | 0.15 | 1.01 | 2.31 |

| Number of asthmatics attended per month | ||||

| 1–20 | 1 | |||

| ≥21 | 0.04 | 1.53 | 1.01 | 2.31 |

| Use of spirometry in pregnant asthmatics | ||||

| Not recommended | 1 | |||

| Initial evaluation or only if symptoms | 0.00 | 6.28 | 4.17 | 9.47 |

| Monthly | 0.00 | 22.07 | 9.50 | 51.30 |

Asthma is the most common medical condition encountered during pregnancy, occurring in 3% to 8% of pregnant women.1 Asthma guidelines have addressed the management during pregnancy but no studies have previously evaluated the adherence, knowledge and attitudes of physicians in this particularly setting. Even though our study has a number of limitations: groups are not uniform, questionnaire was not previously validated, and physicians are not necessarily representative because only those attending scientific meetings were evaluated, it shows significant differences amongst the four professional groups studied regarding the adherence to guideline recommendations about asthma and pregnancy.

It is clear to us that the potential adverse effects of the medication on the developing foetus are a concern that is taken into consideration by every physician attending pregnant patients. In this sense, many health care professionals surveyed seem to consider that the risk of asthma therapy outweighs the potential benefit to be obtained or the risk of not or under-treating. This conservative attitude could explain that primary care physicians (33.7%), obstetricians (25.8%), and allergists (26.8%) responded that they would use on demand medication when asked about their attitude regarding maintenance asthmatic therapy during pregnancy if patient is clinically stable. But, surprisingly, on the other hand, many considered that the concept of asthma control vs. potential drug adverse effect is an important issue to be transmitted to the patient. Although this was significantly more predominant in pneumologists (69.9%) and allergists (73.7%) in comparison to primary care (46.3%) or gynaecology–obstetricians (42.9%). There is a large body of evidence indicating that pregnant women reduce their asthma medications during pregnancy.4,10,11 It is not clear whether these changes reflect changes in the attitudes of pregnant women themselves or to altered prescribing practices of their physicians. In one study this was attributable to altered treatment of pregnant women with asthma during emergency department visits. Pregnant asthma patients, despite having similar symptoms and lung function to those in a non-pregnant women group, were less likely to be treated with oral corticosteroids either in the emergency department or after discharge from hospital.12

Diminished lung function during pregnancy is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes13,14; it is therefore important to monitor pulmonary function. Additionally, it helps to distinguish an exacerbation of asthma or physiological progesterone induced hyperventilation dyspnoea.15,16 Spirometry can be performed safely during pregnancy. Measurement of peak flow rate (PEFR) offers the advantages of less expense and ease of serial measurements at home. It points out that 181 (40.6%) primary care physicians and 50 (31.4%) of gynaecologists–obstetricians thought that spirometry is not recommended during pregnancy and 252 (56.6%) and 106 (67.9%), respectively would only use spirometry if the patient is symptomatic or as an initial evaluation but not as regular lung function monitoring. One of the reasons generally offered to explain the low utilisation of spirometry in primary care has been the limited availability of equipment. In a Spanish study that analysed the use and quality of spirometry, available in 90% of primary care health centres of Navarre, detected a marked underuse of these devices and little compliance with recommendations.17 Furthermore, the quality of the measurements performed in this care setting was very low. On the other hand, the system through which personnel are contracted and the possibility of movement in the position held by nursing staff in Spain makes it very difficult to obtain appropriately trained staff with continuity of roles in all health care centres. An option to consider is to achieve sufficient availability of centralised outpatient pulmonary function units that are easily accessed by pregnant asthmatic women and have adequately trained professionals who are specifically dedicated to the task and supervised in some way by specialists.

Immunotherapy is the only disease-modifying treatment for allergic rhinitis and asthma. The initiation of immunotherapy is not recommended during pregnancy based upon risk–benefit consideration.18 However, aside from the risk of systemic reactions, allergy immunotherapy appears safe during pregnancy,19,20 and it is recommended that allergen immunotherapy be continued during pregnancy in patients already receiving it who appear to be deriving benefit, who are not prone to systemic reactions, and who are receiving a maintenance or at least substantial dosage.18,21 What most primary care physicians (57.4%) and gynaecologists–obstetricians (64.2%) believe is that the decision of maintenance SIT during pregnancy should to be taken by the specialist. In our study, 69 (35.8%) pneumologists seem to adopt a more conservative attitude choosing to withdraw SIT.

This study confirms that important efforts still have to be made in not just bringing the information to the professionals but rather in changing their attitude. Knowledge of guidelines is many times achieved but this does not necessarily translate into changes in routine clinical practice.22–24 The latest version of the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) addresses this issue.25 The problem is how to change attitudes so that knowledge (evidence) can be translated into action (good practice) in asthma patients and health care professionals, particularly, during pregnancy.

Various measures have been proposed recently: the use of personal data assistants,26 which have proven to be highly effective aids to therapeutic decision making27; the integration of action checklists into routine clinical practice in such a way that they are required to be filled in and confirmed28; educational programmes targetting small groups organised as workshops or seminars29; simplification of messages organised in tables, flow charts, and algorithms30; emphasising the great benefits to patients that can be attained if guidelines are followed when designing the content of educational programmes31; and providing the practitioner with basic resources (a standardised medical history, spirometry, peak flow measurements), particularly in the primary care setting.32 Additionally, the routine use of lung function tests should be encouraged.

We have identified significant differences amongst the four professional groups studied in the adherence to guideline recommendations about asthma and pregnancy not associated to the geographic region but rather to the number of asthmatic patients attended, the speciality and the declared use of guidelines. In order to avoid contradiction in the messages transmitted to a pregnant asthmatic patient, our findings could contribute to the development of training programmes that specifically target primary care physicians and gynaecologists/obstetricians. Other health care professionals (i.e. nurses) attending asthmatic pregnant patients should probably be included, although their actual knowledge, attitude and adherence was not evaluated in this study. It has to be taken into account that 82% of pregnant women with asthma indicated in a 2003 survey who used inhaled corticosteroids were concerned about the effects of this medication on the foetus and 36% would discontinue treatment without seeking advice of their physician.33

Pregnancy is a period of emotional lability and our efforts should focus in transmitting clear and unified messages about asthma by all healthcare professionals involved.

Conflict of interestStudy supported by GSK, Spain.

Study supported by GSK, Spain.

Blanco M, Casas X, Cebollero P. Cimbollek S. Costa R, Dominguez J, Garcia-Abujeta JL, Hinojosa B, del Castillo D., Ojeda P, Martinez-Moragón E, Perez-Camo I. Plaza V, Quirce S. Ramos J, Rosado A, Sabadell C, Souto A, Pérez-Llano L and Urrutia I.

Data of this study has been presented at following scientific meetings: (1) 43° Congreso Nacional de la SEPAR (A Coruña, 25 a 28 de junio de 2010). (2) XVII Congreso de la Sociedad Española de Alergología e Inmunología Clínica. Madrid 10–13 de Noviembre, 2010.

See Appendix A.