Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines were developed in recent decades to reduce the burden of pneumococcal diseases. Little is known about paediatricians’ perspectives on the use of pneumococcal vaccine.

ObjectiveWe aimed to examine physicians’ self-reported beliefs and attitudes about the pneumococcal vaccine and their daily clinical practice concerning immunisation against pneumococci in healthy and asthmatic children before the introduction of a nationwide vaccination program.

MethodsA questionnaire survey was applied to the paediatricians attending a national paediatrics congress in 2008.

ResultsOf the 265 paediatricians, 167 responded to the questionnaire. Most (74.5%) believed that antimicrobial resistance could be reduced with the use of the vaccine. 88.5% of the paediatricians declared the pneumococcal vaccine to be a safe vaccine and agreed that the polysaccharide conjugate vaccine-7 should be added to the national vaccination programme. Nearly half of the paediatricians believed that asthmatic children vaccinated with pneumococci had fewer and less severe asthma attacks. 40.0% of the responders stated that the pneumococcal vaccine should be reserved for severe asthmatic children. As the duration of experience increases, the number of patients evaluated per week decreases, and the physicians working in the outpatient clinics tend to vaccinate all children.

ConclusionDespite the paediatricians’ belief in the necessity and importance of the pneumococcal vaccine, none of the examined factors influenced their clinical practice. As the asthma guidelines become clearer regarding the effect of pneumococcal diseases in asthmatics, the perspective of paediatricians may evolve towards greater immunisation.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is an important cause of infection during childhood, leading to considerable morbidity and mortality particularly in young children.1 The 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV-23) and the protein-polysaccharide conjugate vaccine (PCV-7) were developed in the last decades to reduce the burden of pneumococcal diseases. With the use of PCV-7 in the United States, the invasive pneumococcal disease rate decreased from an average of 188 cases per 100,000 to 59.0 per 100,000 (69% total decline). The rate of disease caused by vaccine-related serotypes declined by 50%.2

Bronchial asthma, the major chronic pulmonary disease in childhood, is triggered generally by respiratory tract infections, one of which is mainly pneumococcal in origin.3 A recent study identified asthma as a risk factor, with an odds ratio of 2.4 for invasive pneumococcal disease.4 Recognising this interaction between asthma and pneumococcal infections, some guidelines recommend pneumococcal vaccination in asthmatic children.5

Nowadays, Turkey is close to launching a mass vaccination campaign with PCV-7 in children under 2 years of age. A nationwide vaccination programme may have direct or indirect health effects that may be anticipated or unanticipated; although these effects are intended to be beneficial, some potentially adverse effects may occur.

In this study, we aimed to examine physicians’ self-reported beliefs and attitudes about pneumococcal vaccine and their daily clinical practice concerning immunisation against pneumococci in both healthy and asthmatic children before the introduction of a nationwide vaccination programme.

MethodThe study was designed to include paediatricians who attended the 44th Turkish National Paediatrics Congress in 2008. None of the physicians was informed of the study before the meeting. The questionnaires were distributed during the morning meeting and collected at the end of the scientific sessions. The survey was prepared by the authors based on national immunisation and asthma guidelines. The questionnaires were validated on a sample of 20 physicians through 20 in-depth interviews. The questionnaire sought to obtain the following:

- i)

Demographic characteristics of physicians (gender, age, years of experience in medical practice, number of patients per week, percentage of asthma patients per week, information regarding the patients who had invasive pneumococcal disease in the last year who were either healthy previously or with a diagnosis of asthma, and the source of the physician’s knowledge about the immunisation guidelines (scientific meetings, literature, web, drug industry, Ministry of Health)

- ii)

Perception of pneumococcal vaccine

- iii)

Use of pneumococcal vaccine in clinical practice

- iv)

Use of pneumococcal vaccine in children with asthma.

An explanatory statement was provided at the beginning of the questionnaire. Aside from the items related to demographics, the questions were prepared as statements to be answered on a 5-point Likert scale, with minimum and maximum scores of 0 and 4, respectively, reflecting the physician’s practice. The response scale was anchored as follows: 4 for complete agreement, 3 for agreement, 2 for neither agreement nor disagreement, 1 for disagreement, and 0 for complete disagreement. Responders were given the opportunity to include comments if they wished to do so. The responders were assured of the voluntary nature of the survey and of the confidentiality of all survey responses. Because this survey was non-interventional, no ethics committee approval was required. Results were expressed as the percentage of positive responses to each question. Mean scores above 2 were accepted as agreement, equal to 2 as neither agreement nor disagreement and below 2 as disagreement. Simple random sample methods were used to calculate 95% confidence intervals. All analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical software version 10.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

ResultsOf the 837 paediatricians attending the congress, 265 participated in the major symposium where the survey was conducted, and 167 responded to the questionnaire (response rate: 63%). The characteristics of the study population are summarised in Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Characteristics | Physicians (n=167) |

| Gender (Male/Female) | 84/83 |

| Age (year) | 38 (33–63) |

| Duration of experience (year) | 14 (2–41) |

| Number of patients per week | 208 (15–500) |

| Asthmatic patients per week (%) | 10 (5–18.7) |

| Number of IPD* patients in last year (%) | |

| <5 patients | 52.5 |

| 6–10 patients | 15.8 |

| >10 patients | 31.6 |

| Number of IPD patients with asthma in last year (%) | |

| <5 patients | 71.1 |

| 6–10 patients | 11.8 |

| >10 patients | 17.1 |

| Primary work place (%) | |

| Outpatient clinic | 41 (25.8%) |

| Hospital | 77 (48.4%) |

| Training hospital | 41 (25.8%) |

The questionnaire consisted of three categories: The first category addressed paediatricians’ general knowledge about the pneumococcus vaccine. 74.5% believed that antimicrobial resistance could be reduced with the use of the vaccine. The majority of paediatricians (84.1%) noted that the age of the patient was important for deciding vaccine type, and most (75.8%) believed that the PCV-7 immunised children less than 2 years of age, whereas 68.8% of paediatricians declared the PPV-23 as being ineffective in the same age group. Most of the paediatricians (64.3%) were aware of the coverage of the PCV-7 and answered that the vaccine was not protective against all serotypes.

The second part of the questionnaire concerned the beliefs and attitudes of the paediatricians about pneumococcal infection and the vaccine. Paediatricians accepted pneumococcal pneumonia as a serious event in children (72%). A significant proportion of the paediatricians (88.5%) declared the pneumococcal vaccine as a safe vaccine and offered the PCV-7 to all children (75.8%), so most (78.3%) agreed that the PCV-7 should be added to the national vaccination programme. However, 78.3% of the paediatricians found the vaccine expensive and nearly half of them noted that parents could not afford it. Of the responders, 23.6% accepted that the PCV-7 may have caused confusion regarding the application of other vaccines. In addition, 91.7% of the paediatricians indicated that the PCV-7 vaccine could be used at the same time as other vaccines. Most of the responders (68.8%) perceived the pneumococcal vaccines to be equally as important as the other childhood vaccines.

The last section of the survey concerned the relation of pneumococci and asthma. Nearly half of the paediatricians believed that asthmatic children vaccinated with pneumococci had fewer and less severe asthma attacks. 40.0% of the responders stated that the pneumococcal vaccine should be reserved for severe asthmatic children. Some of the paediatricians (47.5%) noted that the effect of the pneumococcal vaccine in asthma treatment and control was important (Figure 1).

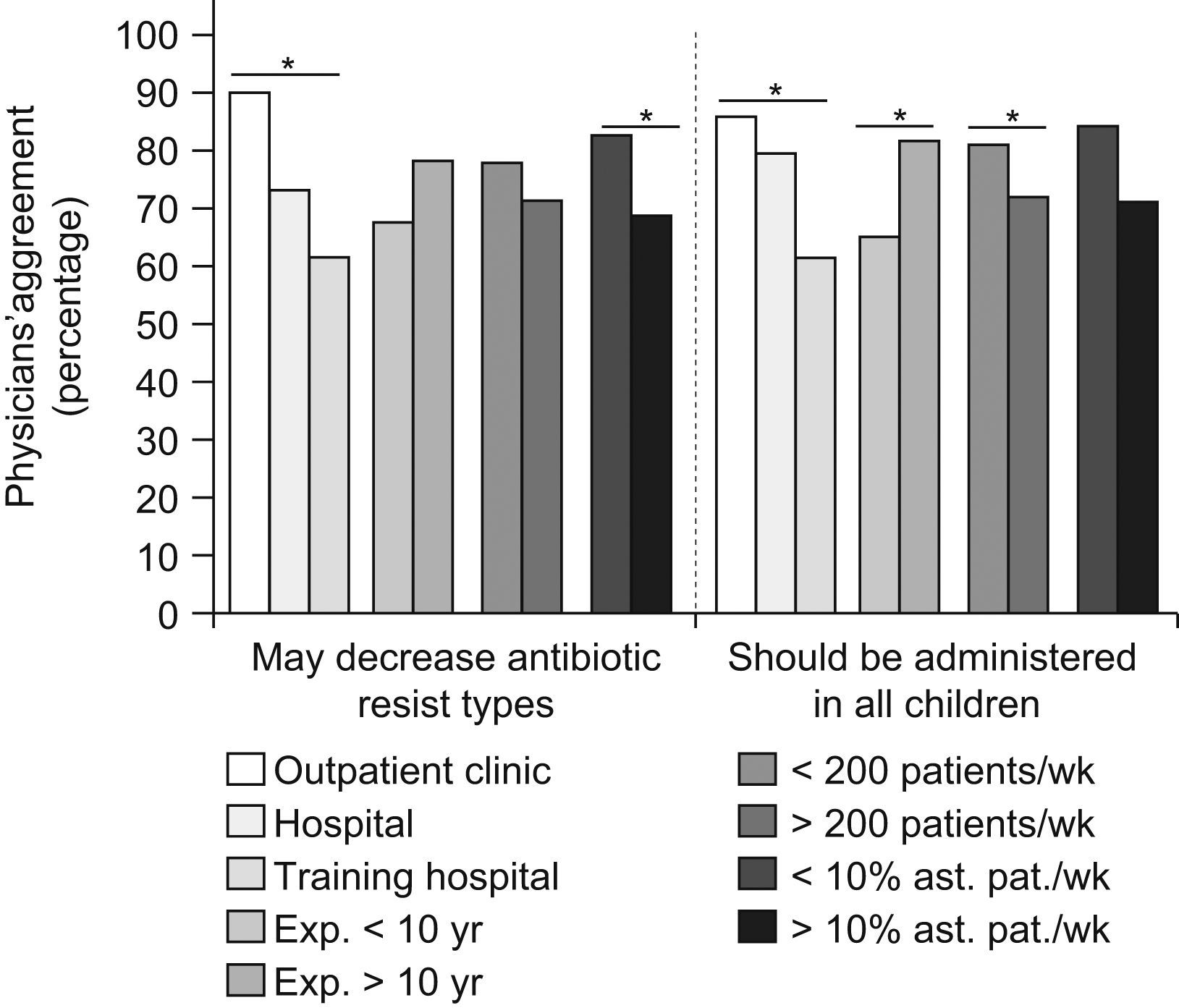

Factors affecting preferences and attitudes: The answers to each question were analysed on the basis of the duration of experience, number of patients and percentage of patients with asthma per week, number of patients with invasive pneumococcal disease in the last year with or without asthma, and primary workplace (Table 2). As the duration of experience increased, the number of patients evaluated per week decreased, and the physicians working in the outpatient clinics tended to vaccinate all children (Figure 2). However, analysis of parameters both with univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis did not show any independent risk factor for the physician’s clinical practice. Thus, despite the differences in beliefs of the different physician groups, none of the parameters led to changes in their daily practice.

Paediatricians’ answers to some questions according to different characteristics of the physicians

| Primary work place | Duration of experience | Patients per week* | Patients with asthma per week** | Patients with IPD in last year** | ||||||||

| Questions | Outpatient clinic | Hospital | Training hospital | <10 years | >10 years | <200 | >200 | <10% | >10% | <5% IPD | 6–10% IPD | >10% IPD |

| Expensive | 80.5 | 75.3 | 82.9 | 82.5 | 75.7 | 82.1 | 75.6 | 86.90 | 72.90 | 84.3 | 76 | 72 |

| Safe | 90.2 | 87 | 90.2 | 87.7 | 88.3 | 91 | 86.7 | 98.40 | 82.30 | 89.2 | 100 | 84 |

| Should be added to national vaccination programme | 80.5 | 77.9 | 78 | 71.9 | 81.6 | 77.6 | 78.9 | 86.90 | 72.90 | 78.3 | 92 | 74 |

| May decrease antibiotic-resistant serotypes | 90.2 | 72.7 | 61 | 66.7 | 77.7 | 77.6 | 71.1 | 82.00 | 68.80 | 80.7 | 64 | 70 |

| Not protective against all serotypes | 73.2 | 62.3 | 61 | 59.6 | 67 | 70.1 | 62.2 | 68.90 | 62.50 | 65.1 | 60 | 68 |

| Age is important for type and number of vaccines | 87.8 | 84.4 | 80.5 | 80.7 | 85.4 | 83.6 | 84.4 | 88.50 | 81.30 | 88 | 84 | 80 |

| Should be administered in all children | 85.4 | 79.2 | 61 | 64.9 | 81.6 | 80.6 | 72.2 | 83.60 | 70.80 | 79.5 | 72 | 74 |

| Vaccinated asthmatic child has fewer exacerbations | 43.9 | 53.2 | 34.1 | 42.1 | 47.6 | 38.8 | 50 | 47.50 | 43.80 | 42.2 | 44 | 54 |

| Vaccinated asthmatic child has less severe exacerbation | 39 | 46.8 | 39 | 40.4 | 43.7 | 37.3 | 45.6 | 36.10 | 45.80 | 33.7 | 40 | 60 |

| Important in the control of asthma | 41.5 | 53.2 | 43.9 | 47.4 | 47.6 | 43.3 | 51.1 | 42.60 | 50.00 | 43.4 | 52 | 54 |

| Pneumonia affects asthmatic children more | 65.9 | 75.3 | 61 | 64.9 | 70.9 | 65.7 | 71.1 | 73.80 | 65.60 | 67.5 | 68 | 74 |

In number, ** Percentage, IPD: Invasive pneumococcal disease.

Pneumococcal infection is an important cause of morbidity and mortality especially in young children. In this study, we found that most of the physicians indicated that PCV-7 should be added to the national vaccination programme. We also searched the factors affecting the decision of paediatricians regarding pneumococcal vaccination in both healthy and asthmatic children.

The paediatricians who were more experienced, working in an outpatient clinic and treating fewer patients per week responded in favour of recommending pneumococcal vaccines to all children. This shows that as the physician spends more time with a patient, he/she focuses on more detailed and complementary issues like vaccination rather than the acute problems. Surprisingly, despite the differences among the physicians with respect to the different factors, none of these parameters affected their daily practice.

In our study, most of the paediatricians reported that resistant pneumococcus strains could be reduced with pneumococcal vaccination. Nasopharyngeal carriage of antibiotic-resistant pneumococcus strains is an important problem. With the use of low doses, prolonged administration times, and inappropriate antibiotics, resistance and carriage of pneumococcal strains have increased significantly. Nasopharyngeal colonisation of pneumococci is inversely related with the age and number of persons living at home. It seems that pneumococcal vaccination may decrease nasopharyngeal colonisation and resistance to antibiotics.2,6

Sixty-four percent of the responders declared that the pneumococcal vaccines were not protective against all serotypes. In a recent study from Turkey, serogroups 23, 19, 6 and 9 were the most common serogroups isolated from healthy carriers and those with invasive diseases and were also among the most frequent penicillin- resistant invasive pneumococci. The data obtained from this study revealed that PCV-7 covers 32% of invasive pneumococci and 46% of penicillin-resistant invasive pneumococci.7 This was a conflicting result for the Turkish paediatricians who intend to use PCV.

In fact, many of the studies concerning the pneumococcal vaccines are primarily based on the information from developed countries and the estimation and extrapolation of limited local data.8–11 Since the 23-valent PPV is not recommended for young children under two years of age, it cannot be used for routine immunisation. PCV-7 has a limited coverage of serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal diseases in developed countries. However, the coverage rate for Africa is 67%, for Latin America 63%, and for Asia 43%.12,13 According to our local results, PCV-7 does not seem to cover the serotypes mostly seen in Turkey.7 There is a need for well-designed, nationwide and multi-centric studies to clarify the serotypes of pneumococci in Turkey. In addition, we do not know the exact number of the pneumococcal infections in our country and as such, the urgency of the pneumococal vaccines should be clarified and discussed.

Respiratory tract infections are well-known triggers of acute asthma; attacks with pneumococci being the most frequent bacterial causative agents.3 However, the role of routine pneumococcal vaccination in people with asthma is unclear. Within the international guidelines concerning asthma, there is no obvious recommendation for the routine pneumococcal vaccination of asthmatic children, and in some guidelines there are conflicting recommendations. For instance, in the German guideline (STIKO, National Board for Immunization), chronic medical conditions (e.g. lung disease) are mentioned broadly as an indication for pneumococcal vaccination,5 whereas American guidelines (Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases) restrict its application to asthmatics requiring oral corticosteroids.8 Furthermore, in the literature, the efficacy of the pneumococcal vaccine in asthmatic children in preventing asthmatic attacks is not clear, and a pragmatic randomised controlled trial to establish the efficacy of pneumococcal vaccination in preventing morbidity and mortality in people with asthma is needed.14 In our study, we found that the perspectives of Turkish paediatricians about the pneumococcal vaccine were consistent with the literature and asthma guidelines.5,8,14 The responses of paediatricians to the items such as “the effect of pneumococcal pneumonia on asthmatic children, the protective effect of the vaccine on attacks and control of asthma” were conflicting. However, in a study reported in 2005 by Talbot et al., asthma was defined as an independent risk factor for invasive pneumococcal disease, and the relative risk was found to be 2.4 times greater among persons with asthma.15 With the support of these studies, the perspective of the paediatricians would shift towards more vaccination with pneumococcal vaccines. In our study, in response to the item concerning the effect of pneumococcal pneumonia on asthma, most of the responders declared pneumococci as a risk factor for hospitalisation. This finding was consistent with the literature.3,4.

There are some limitations to this study. First, self-reported behaviour may not accurately reflect actual clinical practice.16 Physicians’ tendency to give socially acceptable answers would bias against variability in reported practices, underestimating the non-adherence. Second, we were unable to confirm whether survey responders had practices and attitudes that differed from those of non-responders. Finally, as the asthma guidelines and other guidelines about the pneumococcal vaccines become clearer, paediatricians’ behaviours, practices and perspectives regarding the application of pneumococcal vaccination will also be clarified.

In conclusion, Turkish paediatricians strongly support the PCV for routine vaccination to prevent infections that carry a significant morbidity and sometimes mortality. Since some of the physicians may be slow in adaptation to the new vaccines, there should be educational programmes directed towards these groups in a nationwide strategy. Because of the hesitation of some physicians to apply multiple vaccines at the same time, causing delay in some vaccines, such actions can result in periods with lower vaccination rates.