Despite adequate administration of daily controller medication, the number of children with uncontrolled asthma is considerably high and reduced quality of life is observed in both parents and children with poor control.1 Multiple psychosocial problems can contribute to poor asthma control in a similar proportion to poor treatment adherence.2 From previous studies of psychosomatic families, it has been postulated that there are certain stereotypical types of organisation within them such as agglutination, reciprocal overprotection, rigidity and avoidance of conflict.3 These types of family patterns are highly related to the development and maintenance of psychosomatic symptoms which play an important role in the homeostasis of the family.4

From a systemic perspective, the family becomes the protagonist in the symptoms of the indicated patient (scapegoat). The objective of the present study was to identify behavioural patterns within the family unit with respect to the asthmatic patient with uncontrolled asthma and living in extensive families, putting emphasis on authority and hierarchy in such families.

Seven extensive families with a child between the ages of 6 and 11 years old with uncontrolled asthma, confirmed when 19 or less points were reached by children after application of the asthma control test.5 Children's data were obtained from the database of the Institute for Scientific Research in Family, Allergy and Immunology in Morelia, Mexico, in May, 2008. Ten extensive families with a child with uncontrolled asthma were initially considered to be included in the study, but only seven of them finally decided to participate in it.

Family functioning was evaluated in nine different areas with Dr. Emma Espejel Acco's Scale of Family Functioning6 as a reference base. This scale was chosen because it could attain the desired objective and because it was standardised for the Mexican population with a sensibility of 0.91 to discriminate between dysfunctional and functional families. This instrument is also 0.94 accurate when applied by our team of psychologists who are trained in their application and interpretation. Furthermore, a questionnaire was used to study clinical and demographical aspects in the sample population.

In this study, 95% was considered statistically significant using Student's t test and Pearson's correlation was used to analyse the relation between two areas of family function and written informed consent was obtained from participant families. The protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

Reviewing the clinical and demographical data from the population poll it was obtained that in 71.4% of the families the child who was diagnosed with asthma was 9 years old, the rest of the children who suffered from asthma were seven and 12 years old. In 57.1% (four families) of the population polled the child with asthma was male. It was found that 85.7% of the children with asthma were attending primary school between years 1 and 4; 71.4% of the children diagnosed with asthma lived with their parents and grandparents; and 57.1% of the children did not participate in extracurricular activities.

In 85.7% of the families studied, the asthmatic child had at least one brother/sister, and in 57.2% of the families the brother/sister was the eldest of the children. It was found that the amount of years spent in school was higher for the mother than for the father (p<0.05). In 85.8% of the children it was found that they were diagnosed with asthma in a period of 5–10 years before and 42.9% received at least one treatment for asthma. In 71.5% of the families, the treatment for the child was administered by at least one specialist (paediatrician or allergist). 85.7% of the families acquired a physician for their child's treatment, 57.1% of the children suffered an asthmatic crisis every six months, of which these occurred 2.7 times more frequently at night than in the morning or afternoon. A family history of asthma was found in 57.1% of the families with asthmatic children. Of all the children studied, the most important catalyst for the asthmatic crises were environmental factors.

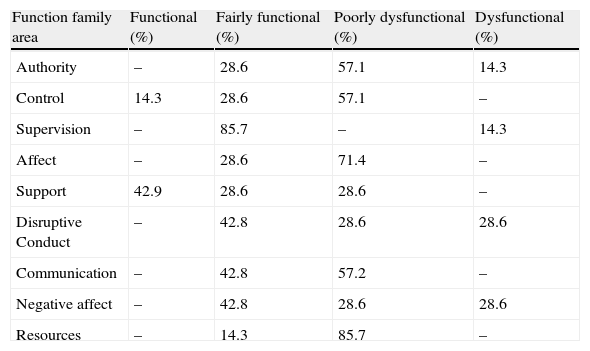

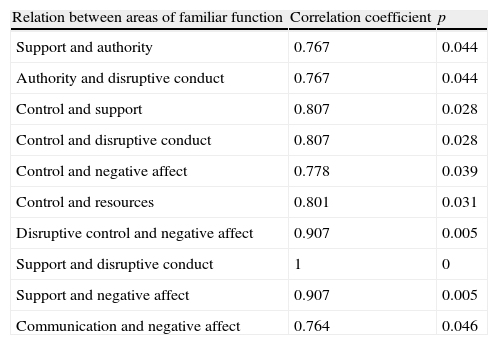

The results obtained via the Scale of Family Functioning are shown in Tables 1 and 2 where families were characterised considering areas of family functioning and the most important correlations found among them, respectively. The major parts of the evaluated areas were affected: control, supervision, affect, disruptive conduct, communication, negative affect and resources, were fairly to poorly functional mainly, however the 42.9% of the families were functional in the area of support. The most significant positive correlations observed among studied areas were between support and disruptive conduct (p<0.001), between disruptive conduct and negative affect (p=0.005), between support and negative affect (p=0.005), between control and support (p=0.028) and between control and disruptive conduct (p=0.028).

Families according to areas of the Espejel Acco's Scale of Family Functioning.

| Function family area | Functional (%) | Fairly functional (%) | Poorly dysfunctional (%) | Dysfunctional (%) |

| Authority | – | 28.6 | 57.1 | 14.3 |

| Control | 14.3 | 28.6 | 57.1 | – |

| Supervision | – | 85.7 | – | 14.3 |

| Affect | – | 28.6 | 71.4 | – |

| Support | 42.9 | 28.6 | 28.6 | – |

| Disruptive Conduct | – | 42.8 | 28.6 | 28.6 |

| Communication | – | 42.8 | 57.2 | – |

| Negative affect | – | 42.8 | 28.6 | 28.6 |

| Resources | – | 14.3 | 85.7 | – |

Support: refers to the form in which the family members provide social support within and outside of the family nucleus. Authority: efficiency of authority within the family. It is considered as more functional in families where the authority resides in a parental subsystem, which is shared by both parents. Disruptive conduct: this deals with the handling of inappropriate social behaviour such as addictions, problems with authority or other emerging situations. Affect: the way in which the family express the sates of wellbeing or discomfort. Control: how the family manages limits and methods of behavioural control and the families with well established limits that are respected are considered more functional. Negative affect: how the presence of negative feelings and emotions functions within the family. Supervision: put emphasis in rules permitted by the family and their accomplishment. Resources: refers to the existence of potential affective instruments and the family's capacity to utilise and develop them. Communication: evaluates the form in which verbal and non-verbal expression functions within the family.

Relation between areas of Family Function.

| Relation between areas of familiar function | Correlation coefficient | p |

| Support and authority | 0.767 | 0.044 |

| Authority and disruptive conduct | 0.767 | 0.044 |

| Control and support | 0.807 | 0.028 |

| Control and disruptive conduct | 0.807 | 0.028 |

| Control and negative affect | 0.778 | 0.039 |

| Control and resources | 0.801 | 0.031 |

| Disruptive control and negative affect | 0.907 | 0.005 |

| Support and disruptive conduct | 1 | 0 |

| Support and negative affect | 0.907 | 0.005 |

| Communication and negative affect | 0.764 | 0.046 |

Clinical and demographical data showed poor control of asthma, unsatisfied demands of medical assistance, frequent familiar history of allergies, and deficient social insertion of the asthmatic children in community, which is in close relation with the recurring behaviour of the psychosomatic system. The fact that the majority of the areas of the Scale of Family Function revealed families with fairly functional or poorly functional behaviour, indicates rigidity in the system. The correlations found among areas of family function indicate that when the efficiency of authority is high the family members provide social support within and outside the family nucleus, and when this support exists the family well manage limits and methods of behavioural control. On the other hand when the control is high the family can modulate the presence of negative feelings and emotions, recognising the existence of potential affective instruments and their capacity to use them is also activated. Authority and control were associates with an efficient management of inappropriate social behaviour and when support was high the families responded to the presence of negative feelings, which was excellent, when verbal and non-verbal expressions functions were not compromised.

Considerable attention causes the existence of coalitions against parents of the children with uncontrolled asthma in three from seven of the studied families, these coalitions were grandfather and grandmother against mother and father (1/7 families); grandmother and his daughter against mother (1/7 families); and grandmother and grandfather against father (1/7 families). With respect to the hierarchies, in 1/7 families the father/grandfather was the chief member, in one family both grandparents wielded the power predominantly and in two families the power was exercised by the father/husband mainly, despite the existence of higher academic levels in mothers than those found in fathers and grandparents. Succession and inheritance factors and poverty status of families living in more than two generations of its members could be linked to this behaviour in our environment, it demands further studies.

On another note, the studied families were resistant to change, presenting themselves contrastingly united and harmonious with only one clear problem; the child's illness. External relationships were scarce and the family clings to preservation of their own homeostasis, debilitating exchange with their social surroundings, said in other words, they avoid all contact or informational feedback becoming a closed system. The rigidity was reflected once the negative behaviour was analysed and affection control management explored via the scale of family functioning. All this leads to unsolved conflicts that become cyclical, being inherited from one generation to another. An area that reflects this characteristic is resource, due to the fact that it is poorly functional, which indicates that the family does not know how to use them, it has the resources, but it is not allowed to use them or the family cannot identify the way to use them.

The children of these families are subject to a type of behavioural alignment in which they are boxed in and obliged to maintain the family dynamics. In a family where one supports the other, moved by the ideal of reciprocal hyper-protection, the patient becomes the one who most needs the care. On the other hand, when tension arises in the family with a possible argument, the subject of the argument becomes secondary as the patient enters the scene and suppresses the subject as all are concerned for his/her health and wellbeing in accordance with Minuchin.4

The parent's deficiencies to fulfil the child's needs in each phase of his/her development, could explain certain psycho–physiological disorders in their children. It is observed that the scapegoat, the victim of an attack, is the member that becomes the object of attacks provoked by prejudices, and suffers emotionally which makes him/her susceptible to emotional breakdown at various levels.7,8 Unlike a similar study conducted in nuclear families with children with asthma,9 extended families in this study showed greater commitment in the areas of authority, supervision and disruptive conduct, which are related to the poor allocation of authority between parents and the existence of alliances or coalitions that hinder the development of the family.

The results obtained via the Scale of Family Functioning showed that all evaluated areas of family functioning could be affected in extensive families with a child with uncontrolled asthma, even when the majority of them were in the range of fairly functional to poorly functional. Their evaluation in families in which children remain with uncontrolled asthma despite adhesion to pharmacological treatment and the analysis of correlations among such areas should be used to detect families needing psychotherapeutic assistance to reach a better control of the disease. Recommendations for future research include the validation of the Espejel Acco's Scale of Family Functioning in other cultures and replication of the study with a larger sample of children with uncontrolled asthma comparing their families with those of children with controlled asthma.