INTRODUCTION

The term pemphigus encompasses a group of potentially fatal diseases characterized by blister-like skin and/or mucosal lesions (table I) 1,2. Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is one of the more serious presentations that very often leads to serious patient conditions that are difficult to manage on an outpatient basis, and frequently requires intensive care 3.

A close association has been observed between the disease and Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) class II antigens in certain ethnic groups such as those of Mediterranean origin that are susceptible to PV 4.

The physiopathology of PV is characterized by the production of circulating antibodies targeted to desmoglein-3, and in some patients to desmoglein-1 (fig. 1). This in turn conditions the diagnostic options and monitorization of the course of the disease 5,6.

Figure 1.--Pathogenesis of pemphigus vulgaris.

Importance is placed in this study on the existing treatment options, of which the most common are steroids, azathioprine, tetracycline, cyclophosphamide, mofetil mycophenolate, dapsone and methotrexate.

PEMPHIGUS VULGARIS

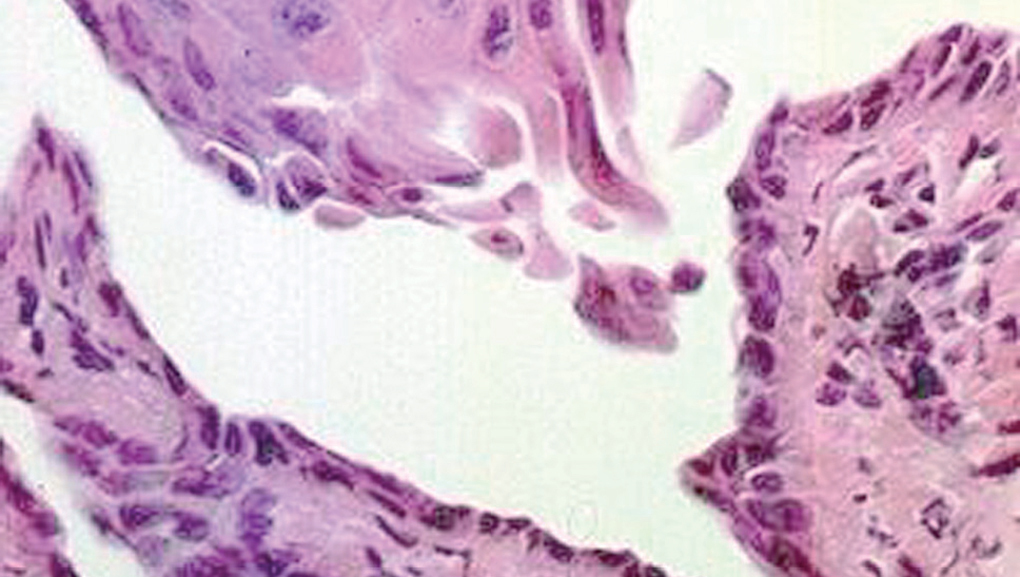

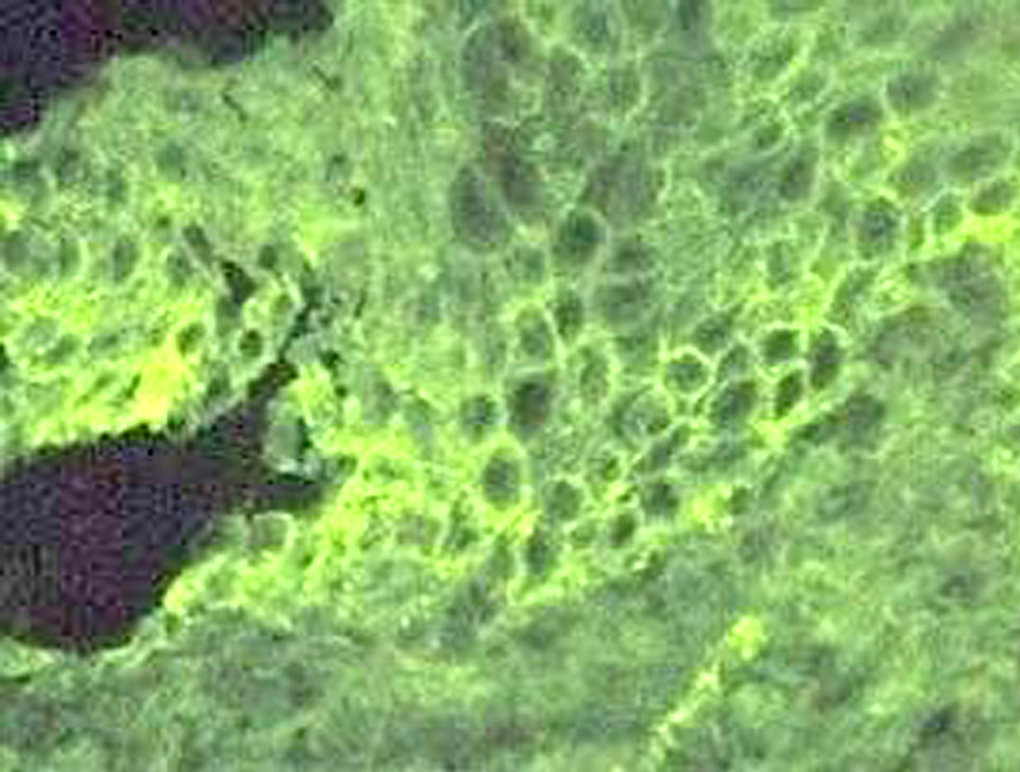

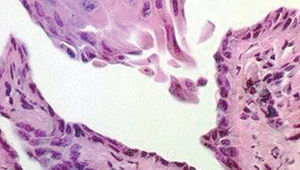

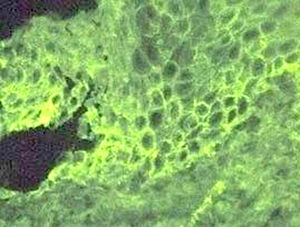

Clinically, PV is characterized by the appearance of blisters with subsequent ulceration on the skin and mucosal membranes (fig. 2). The condition often begins in the oral mucosa and rapidly spreads to the skin (fig. 3). The disease in infrequent, with no patient sex predilection, and exhibits two peak incidences in the third and sixth decades of life, respectively 7. The diagnosis is based on clinical factors, though a histopathological study is practically mandatory (revealing intraepidermal blisters containing acantholytic cells) (fig. 4), along with direct immunofluorescence (DIF) evaluation (revealing the presence of IgG deposits in intraepidermal keratinocytes, with a honeycomb pattern) (fig. 5).

Figure 2.--Presence of ulcerations on the face some covered with blood crusts.

Figure 3.--Dissemination of the disease, with involvement of the chest. Note the characteristic ulcerations.

Figure 4.--Histological view, showing an intraepidermal blister containing acantholytic cells. Hematoxylin-eosin stain, 40x.

Figure 5.--Direct immunofluorescence labeling with IgG deposits among the intraepidermal keratinocytes, forming a honeycomb pattern.

Treatment first aims to achieve disease remission, and this is frequently possible as a result of intensive therapy (often on an in-hospital basis). Such management is then followed by maintenance therapy to stabilize the disease with the administration of systemic medication in progressively decreasing doses.

The principal systemic therapeutic options currently available in Mexico are described below. Their indications, contraindications and side effects are summarized in table II.

Oral steroids

Oral steroids are a basic option for the management of PV in any phase of the disease, and since their introduction have contributed to improve patient survival 8,9 though it is well known that PV can improve even in the absence of treatment, with increased survival over the middle or long term 9.

The benefits afforded by oral steroid use with or without the Lever scheme are great. At conventional doses, these drugs reduce blister outbreaks within 2-3 weeks 10, with complete disease remission in up to 29 % of cases 11.

Prednisone dosing via the oral route is arbitrary, since different management schemes have been developed, and no general consensus has been reached over the best treatment option for PV. The drug dose is empirically adjusted to the severity of the disease, though in most cases a dose of 0.5-1 mg/kg body weight is prescribed, reaching 2 mg/kg/day as required 12.

Steroid dose reduction should be carried out gradually. In our practice we apply weekly 5-mg reductions to 20 mg, followed by weekly 2.5 mg reductions in an attempt to completely obviate the need for such medication while ensuring control of the disease 4,12.

Methylprednisolone or dexamethasone pulses

Steroid pulses have been widely applied to ampullar diseases, and fundamentally to PV, to avoid the complications and side effects of chronic daily oral steroid dosing 13.

The term "pulse" refers to discontinuous intravenous infusion of supratherapeutic drug doses in a short period of time 14. Pulse therapy is recommended as an adjuvant to the initial management plan for patients with more severe PV involvement 15. Methylprednisolone (and dexamethasone) is the most commonly intravenous glucocorticoid. The dose corresponding to each pulse has not been standardized, but ranges from 10-20 mg/kg in the case of methylprednisolone, and 2-5 mg/kg in the case of dexamethasone with a three-hour infusion in 500 ml of 5 % glucose solution. In this context, 500 mg of the former and 100 mg of the latter medication are considered equivalent to 625 mg of prednisone 14.

The mechanism of action of the glucocorticoid pulses comprises the inhibition of acantholysis induced by IgG in PV, as a result of which the spread of keratinocyte deterioration is reduced. The maximum effect is recorded 3-5 days after administration in agreement with the observation of animal studies 16.

The utilization of these megadoses has revolutionized the treatment of PV, for although such therapy is not the first choice management option, it almost always improves patient prognosis when prescribed on an opportune basis.

ADJUVANT DRUGS

The treatment options for PV include substances known as adjuvant drugs, which are agents that support the effect of steroids administered fundamentally via the oral route. Some of these adjuvants act as "steroid sparing agents". The principal representatives are azathioprine and cyclophosphamide. Some of the characteristics of these drug substances will be dealt with briefly.

Azathioprine

Azathioprine is one of the most common adjuvants to PV therapy, and has been shown to be effective in application to many diseases apart from PV, such as bullous pemphigoid and atopic dermatitis 17,18.

While its utility is increasingly acknowledged, the principal side effect of azathioprine (potentially severe myelosuppression) has led to the recommendation of thiopurine methyltransferase testing as a predictor of azathioprine-mediated myelosuppression 18.

The administration of azathioprine as adjuvant therapy in PV increases percentage disease remission up to 45 %. While the drug can be administered as sole therapy, its use in monotherapy (and even more as initial treatment) is not advised, due to the frequency of side effects involved 19.

Azathioprine offers better results when administered at a dose of 1-3 mg/kg for 6 weeks. After this period of treatment, bone marrow function must be carefully monitored 20.

Oral cyclophosphamide

The use of oral cyclophosphamide as steroid-sparing adjuvant therapy in PV has been documented in many reviews published in the literature 21-23. The use of oral cyclophosphamide in monotherapy entails many side effects such as hematuria, overinfection and bladder carcinoma, and remission takes too long to achieve (8 months). In this period of time, the aforementioned side effects very often appear. Consequently, oral cyclophosphamide is not recommended as monotherapy or as a first treatment option 24.

Pulses of cyclophosphamide with methylprednisolone or dexamethasone

PV treatment in the form of mixed pulses or DCP (dexamethasone-cyclophosphamide pulses) has been shown to be effective in application to recurrent PV and refractory presentations of the disease. Introduced by Pasricha in 1988 25, this therapeutic modality has yielded good results in many patients to date 26-28.

The DCP scheme consists of the monthly administration on intravenous dexamethasone (136 mg, which is adjusted to 100 mg for easier use) during three consecutive days, with the addition on the second day of a 500-mg pulse of cyclophosphamide. Posteriorly, 50 mg of oral cyclophosphamide or oral prednisone 0.5-1 mg/kg/day is started, until partial remission is achieved (after about 6 months) the oral dose being continued for up to one year, when complete remission is achieved 27.

The number of DCPs required to induce clinical remission varies according to the severity of PV and the complications of the disease. In a key study on treatment it was considered that 49 % of patients require 6 or fewer pulses to achieve clinical remission though up to 11 % require more than two years of pulse therapy. On the other hand, over 60 % of the patients achieve complete remission (for over two years in 40 % of cases, and for over 5 years in 15 %) 29.

Among the most common side effects of DCP, mention should be made of some mild intensity disorders such as facial rubor, hiccup, diffuse alopecia, insomnia, headache, joint pain, and numbness of the feet. Other effects manifesting with greater intensity comprise hypertension, hyperglycemia, blurry vision with the development of glaucoma, and posterior subcapsular cataracts, palpitations, swelling of the legs, malaise and asthenia. Serious side effects in turn comprise seizures, apnea and even death. The effects tend to be more frequent between 1-2 weeks after the therapeutic pulse 30.

Despite the above effects, the DCP scheme constitutes only a somewhat more aggressive alternative to conventional therapy, and is defined in the third line of treatment for PV. Apparently, it offers prolonged control of the disease, and thus an improved patient prognosis.

Mofetil mycophenolate

Mycophenolic acid has been used for the management of psoriasis during the past three decades; at present, it has been re-formulated as mofetil mycophenolate and is used as an immunosuppressor in transplantation patients (Food and Drug Administration (FDA) 1995) 31. In recent years it has been found to be useful in the management of gangrenous pyoderma, ampullar lichen planus, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and PV 32.

The current uses of mycophenolate in PV have focused on active and steroid-refractory presentations of the disease. When administered as coadjuvant, the drug has been shown to reduce the activity of PV 33. It has been reported that complete remission can be achieved after 9 months of treatment in up to 70 % of cases, apparently with only minimal side effects 34,35.

Although it was initially suggested that the drug could be used in monotherapy with favorable effects over more than 6 months, it is now believed that mycophenolate is better used as adjuvant in cases of active PV yielding superior results and shorter recovery times when administered in this manner 36,37.

Mycophenolate is recommended for recalcitrant cases, or in situations where azathioprine or cyclophosphamide cannot be used 38.

Methotrexate

While the utility of methotrexate as monotherapy for PV has always been the subject of discussion, it is most widely accepted as an adjuvant. In effect, the combination of high doses of methotrexate (up to 125 mg a week are advised) with prednisone 0.5-1 mg/kg/day appears to bring the disease under control within 6 months 39.

Despite evidence of the effectiveness of methotrexate as an adjuvant to therapy in patients with PV, in practice it is difficult to use because of its side effects (mainly at hepatic level). These effects are more likely when such high doses of the drug are used 38,39.

Thus, methotrexate as adjuvant is reserved for those cases of PV in which it is not possible to use some other adjuvant substance such as azathioprine or cyclophosphamide 38.

Tetracycline and nicotinamide

The combination of these two drugs has been tested not only in application to PV but also to patients with foliaceous pemphigus 40,41, discoid lupus erythematosus 42, pemphigus vegetans 43, linear IgA dermatosis 44 and bullous pemphigoid 45.

The combination has been shown to be useful for the treatment of both cutaneous 46 and oral PV 47.

The usually recommended posology is 1.5 g of nicotinamide and about 2 g of tetracycline a day 48, or 50-200 mg of minocycline 49. Adequate treatment responses have been reported with this regimen, though the existing results are not conclusive. In any case, this combination gives rise to few side effects when used as adjuvant therapy, and therefore can be considered in situations where it is not possible to use azathioprine or cyclophosphamide.

Dapsone

Dapsone is one of the most useful agents in application to many diseases, including leprosy. There have been isolated reports on the utility of dapsone in application to PV. In this context, the drug has been postulated to control the levels of antibodies in PV, though the results of an experimental study suggest that dapsone exerts no effects upon serum antibody levels in PV 50. Despite this, case studies have been made involving the use of this drug. It has not been shown to be of use in monotherapy, but can be used as an adjuvant. In any case, the data available to date are not conclusive 51-53.

OTHER TREATMENTS

Many other treatments for PV are also under study, and some have demonstrated good efficacy compared with steroid treatment. Some of these therapies, such as gold salts 54, chlorambucil 55 and cyclosporine 56, are used as adjuvants in the treatment of PV, in association to prednisone or (as in the case of cyclosporine) for the control of disease remission. Such therapies are not recommended as first choice management options, however. Other treatments such as intravenous immunoglobulins 57, plasmapheresis 58 and extracorporeal photopheresis 59 have been more extensively documented. Their application in industrialized countries appears to be frequent, though only in cases that prove resistant to conventional treatment 60, or in relapsing disease. As such, they are viewed as last choice options in the management of PV.

DISCUSSION

While many treatments have been developed for pemphigus vulgaris (PV), none have been shown to offer absolute efficacy in controlling the disease. The management of choice is steroid therapy via the oral or intravenous route, which offers an adequate response and favorably modifies the prognosis.

The drugs described above are only part of the repertoire currently available for the management of PV. The more salient options have been described, in view of their ease of use and accessibility in this country though in the not too distant future we hope also to be able to introduce photodynamic therapy and specific plasmapheresis, among other therapeutic options.

Correspondence:

Andrés Tirado-Sánchez

Servicio de Dermatología

Hospital General de México

Dr. Balmis, 148

Col. Doctores, Deleg. Cuauhtemoc

Distrito Federal, C.P. 06720 Mexico