Background. In clinical practice, it is assumed that a severe rise in transaminases is caused by ischemic, viral or toxic hepatitis. Nevertheless, cases of biliary obstruction have increasingly been associated with significant hypertransaminemia. With this study, we sought to determine the true etiology of marked rise in transaminases levels, in the context of an emergency department.

Material and methods. We retrospectively identified all patients admitted to the emergency unit at Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra between 1st January 2010 and 31st December 2010, displaying an increase of at least one of the transaminases by more than 15 times. All patient records were analyzed in order to determine the cause of hypertransaminemia.

Results. We analyzed 273 patients – 146 males, mean age 65.1 ± 19.4 years. The most frequently etiology found for marked hypertransaminemia was pancreaticobiliary acute disease (n = 142;39.4%), mostly lithiasic (n = 113;79.6%), followed by malignancy (n = 74;20.6%), ischemic hepatitis (n = 61;17.0%), acute primary hepatocellular disease (n = 50;13.9%) and muscle damage (n = 23;6.4%). We were not able to determine a diagnosis for 10 cases. There were 27 cases of recurrence in the lithiasic pancreaticobiliary pathology group. Recurrence was more frequent in the group of patients who had not been submitted to early cholecystectomy after the first episode of biliary obstruction (p = 0.014). The etiology of hypertransaminemia varied according to age, cholestasis and glutamic-pyruvic transaminase values.

Conclusion. Pancreaticobiliary lithiasis is the main cause of marked hypertransaminemia. Hence, it must be considered when dealing with such situations. Not performing cholecystectomy early on, after the first episode of biliary obstruction, may lead to recurrence.

Liver enzymes, routinely used in the evaluation of patients, tend to be elevated in about 7-12%.1 of the Portuguese population. These changes are classically divided into “cholestatic” or “hepatocellular” patterns, according to abnormal parameters: while in cholestatic disorders an increase in alkaline phosphatase and gamma glutamyl transferase prevails,2,3 in hepatocellular disorders the increasing value of aminotransferases is the most predominant. In fact, aminotransferases are considered sensitive indicators of liver injury,4 since increased levels are found on hepatocytes and only small concentrations (up to 40 IU/L) are present in blood circulation in normal situations. When there is a hepatocellular injury with loss of integrity of the hepatocyte membrane, transaminases plasma levels increase. Levels up to 300 IU/L are nonspecific and can be observed in various situations. Conversely, a marked increase of aminotransferases (greater than 15 times the upper limit of normal5) arises in a number of more restricted situations. In the scarce published literature, it is argued that these large increases generally point to a viral, toxic or ischemic hepatocellular damage.5-8

However, in our clinical practice, we have often encountered cases of marked hypertransaminemia associated with biliary obstruction without showing this typical cholestatic pattern. In fact, such kind of situations has increasingly been documented in the literature.9-12

Bearing these predicaments in mind, we undertook this study, with the purpose of determining the actual rate and etiology of severely elevated liver aminotransferases in a Hospital emergency department.

Material and MethodsType of the studyObservational.

Time horizon, Setting and ParticipantsAll patients admitted to the emergency department at Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra (CHUC) between 1st January 2010 and 31st December 2010, displaying an increase of at least one of the transaminases by more than 15 times, were retrospectively evaluated. These patients were identified through computer records provided by the Department of Biochemistry of CHUC. We followed these patients until July 2012.

Study perspective and variablesDescriptive study. We characterized the sample according to the following variables: age, gender, risk factors for liver disease (metabolic syndrome - hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia; alcoholism; hepatotoxic medications), prior cholecystectomy, cancer, thyroid disease, heart failure, symptoms, results of complementary tests (blood tests, abdominal ultrasonography, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, histology), follow-up and final diagnosis.

DefinitionsA marked increase of aminotransferases (hyper-transaminemia) was considered when at least one ami-notransferase (glutamic pyruvic transaminase - GPT or glutamic oxalacetic transaminase - GOT) exceeded 15 times5 the reference upper limit established by the laboratory of the Hospital (45 IU/L), that is, greater than 700 IU/L.

Cholestasis was defined when alkaline phosphatase and/or gamma-glutamyl transferase exceeded the upper normal limit, which is 120U/L and 55U/L, respectively.

We considered the following drugs with potential hepatotoxicity: acetaminophen, amiodarone, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, carbamazepine, fluconazole, glyburide, heparin, isoniazid, ketoconazole, labetalol, nitrofurantoin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, phenytoin, proton pump inhibitors, sulfonylureas, trazodone, allopurinol, azathioprine, captopril, anti-oral contraceptives, corticos-teroids, hydralazine, methotrexate, methyldopa, quinidine and erythromycin.13

We defined abusive alcohol consumption as an intake greater than 40 g/day in males and 20 g/day in females.14

Ischemic hepatitis was considered whenever a marked increase of aminotransferases occurred in a patient with clinical cardiac, circulatory or respiratory failure.15

The elevation of aminotransferases was considered cryptogenic when no cause was found, despite the performed work-up (no alcohol or intravenous drug use or history of ischemic hepatitis, negative abdominal ultrasound, serology and autoimmunity, with or without histo-logical examination).

Ethical approvalAll procedures performed in this study that concerned human participants were in accordance with ethical standards of the institution and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Exceptionally, and given the public health interest of this retrospective study and the observational design of the protocol, it was decided not to send a consent form to the patients. Nonetheless, the authors are able to certify that the data collection by the physician was subject to professional confidentiality and ethical code and that the anonymity of all the participants was guaranteed by the assignment of a unique identification number that was only accessible to the researchers involved with this study. All collected data was treated, published and presented in a grouped manner, in order to prevent the identification of the participants. Only the researchers were granted access to the collected data, and its storage was assured for a 5-year period counting from the last publication until its subsequent destruction. The researchers take full responsibility for the confidentiality of the collected data.

Statistical analysisWe performed a descriptive analysis of patients who presented marked liver aminotransferases elevation in the emergency department [frequency, mean, standard deviation and median]. We described the episode, causes and follow-up. We evaluated the influence of cholecystectomy in the recurrence of hypertransaminemia using the χ2 test. We analyzed the influence of some characteristics (age, presence of cholestasis, the average value of GPT) in the differential diagnosis of altered aminotransferases, through:

- •

χ2 test for comparison of dichotomous qualitative variables, if necessary with continuity correction.

- •

The Kruskal-Wallis test for the qualitative or quantitative analysis ordinal variables. Significant differences were considered whenever p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, version 20.

During the period of study, 152,718 patients were observed in the emergency department of our Hospital. Three hundred and twenty four patients (0.2%) displayed a marked increase of aminotransferases. However, 51 were excluded due to lack of information over their primary diagnosis and/or follow-up.

From the 273 patients included, 146 (53.5%) were male. The mean age was 69 years (15-96 years, standard devia-tion=19.4). Regarding co-morbidities: 48% had arterial hypertension, 40% were under hepatotoxic medication, 21% had dyslipidemia, 20% diabetes mellitus, 12% congestive cardiac failure, 12% alcohol abuse, 9% cancer history, 8% prior cholecystectomy, 5% thyroid disease and 3% history of endovenous drug abuse.

Defining the episodeAbdominal pain was the main symptom observed in most patients (56.6%). Some patients also referred nausea and vomiting (24.5%), jaundice (12.4%), fever (11.7%), dyspnea (11.7%), prostration (8.0%), chest pain (4.0%), syncope (3.6%), myalgia (3.3%) and diarrhea (2.9%). In 204 cases (74.7%), the liver pattern was mixed, that is, associated with cholestasis. Abdominal ultrasound was performed in 204 cases.

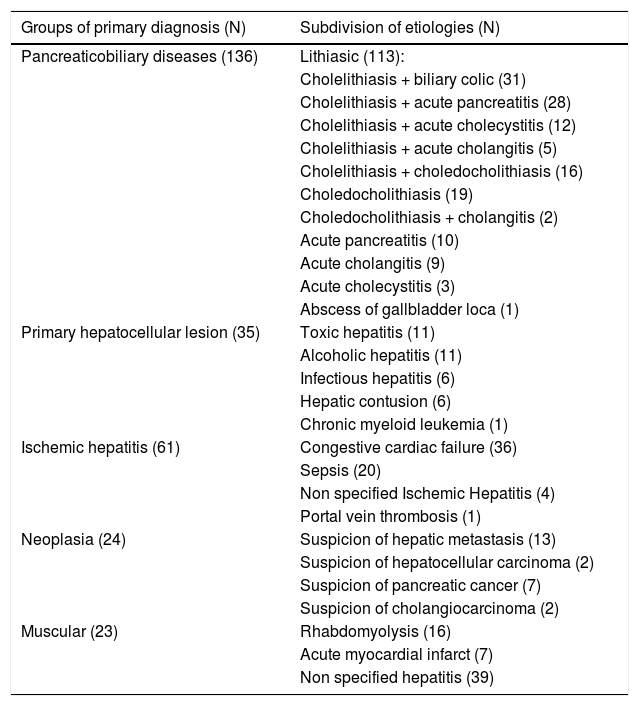

Primary diagnosis of marked hypertransaminemiaA total of 318 diagnoses were documented with regards to 273 patients observed in the emergency room, as stated in Table 1.

Primary etiology of marked hypertransaminemia.

| Groups of primary diagnosis (N) | Subdivision of etiologies (N) |

|---|---|

| Pancreaticobiliary diseases (136) | Lithiasic (113): |

| Cholelithiasis + biliary colic (31) | |

| Cholelithiasis + acute pancreatitis (28) | |

| Cholelithiasis + acute cholecystitis (12) | |

| Cholelithiasis + acute cholangitis (5) | |

| Cholelithiasis + choledocholithiasis (16) | |

| Choledocholithiasis (19) | |

| Choledocholithiasis + cholangitis (2) | |

| Acute pancreatitis (10) | |

| Acute cholangitis (9) | |

| Acute cholecystitis (3) | |

| Abscess of gallbladder loca (1) | |

| Primary hepatocellular lesion (35) | Toxic hepatitis (11) |

| Alcoholic hepatitis (11) | |

| Infectious hepatitis (6) | |

| Hepatic contusion (6) | |

| Chronic myeloid leukemia (1) | |

| Ischemic hepatitis (61) | Congestive cardiac failure (36) |

| Sepsis (20) | |

| Non specified Ischemic Hepatitis (4) | |

| Portal vein thrombosis (1) | |

| Neoplasia (24) | Suspicion of hepatic metastasis (13) |

| Suspicion of hepatocellular carcinoma (2) | |

| Suspicion of pancreatic cancer (7) | |

| Suspicion of cholangiocarcinoma (2) | |

| Muscular (23) | Rhabdomyolysis (16) |

| Acute myocardial infarct (7) | |

| Non specified hepatitis (39) |

- •

Primary destination. We admitted 241 patients (88.3%) for study, stabilization and treatment. Thirteen patients died in the emergency room and 19 cases were discharged home, with the following diagnosis: biliary colic (6), unspecified hepatitis (4), infectious mono-nucleosis (3), liver metastasis (2), toxic hepatitis (1), pancreatitis (1), rhabdomyolysis (1) and chronic mye-loid leukemia (1).

- •

Cholecystectomy. From the 113 patients with lithia-sic pathology, 38 underwent cholecystectomy during the hospitalization after clinical stabilization.

After discharge and during follow-up, 41 patients recurred with increased aminotransferases, 27 of which belonged to lithiasic pathology group (24 out of 75 who were not submitted to cholecystectomy and 3 out of 38 who underwent cholecystectomy).

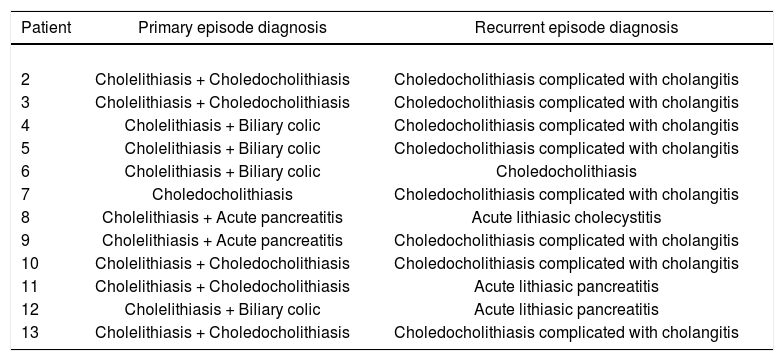

Recurrence was more frequent in the group of patients who weren’t submitted to early cholecystectomy after the first episode of biliary obstruction (p = 0.014). In this subgroup of patients, the second episode of marked hyper-transaminemia was accompanied by a clinical deterioration in 13 cases, as shown in Table 2.

Final diagnosis of recurrent cases with lithiasic pancreaticobiliary disease

| Patient | Primary episode diagnosis | Recurrent episode diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| 2 | Cholelithiasis + Choledocholithiasis | Choledocholithiasis complicated with cholangitis |

| 3 | Cholelithiasis + Choledocholithiasis | Choledocholithiasis complicated with cholangitis |

| 4 | Cholelithiasis + Biliary colic | Choledocholithiasis complicated with cholangitis |

| 5 | Cholelithiasis + Biliary colic | Choledocholithiasis complicated with cholangitis |

| 6 | Cholelithiasis + Biliary colic | Choledocholithiasis |

| 7 | Choledocholithiasis | Choledocholithiasis complicated with cholangitis |

| 8 | Cholelithiasis + Acute pancreatitis | Acute lithiasic cholecystitis |

| 9 | Cholelithiasis + Acute pancreatitis | Choledocholithiasis complicated with cholangitis |

| 10 | Cholelithiasis + Choledocholithiasis | Choledocholithiasis complicated with cholangitis |

| 11 | Cholelithiasis + Choledocholithiasis | Acute lithiasic pancreatitis |

| 12 | Cholelithiasis + Biliary colic | Acute lithiasic pancreatitis |

| 13 | Cholelithiasis + Choledocholithiasis | Choledocholithiasis complicated with cholangitis |

During follow-up, and after further etiologic work-up, 46 diagnoses were changed/added:

- •

Four cases of biliary lithiasic obstruction were associated with a neoplasia – 1 ampullary carcinoma and 3 cholangiocarcinomas.

- •

13 cases biliary lithiasic obstruction were further complicated by cholangitis (8), acute lithiasic pancreatitis (3), choledocholithiasis (1) and acute lithiasic cholecystitis (1);

- •

In the initially “unspecified hepatitis” group, it was possible to achieve the following diagnosis: cholangiocarcino-ma (5), cholelithiasis with biliary colic (3), autoimmune hepatitis (3), pancreatic cancer (2), follicular lymphoma (2), acute alcoholic hepatitis (2), toxic hepatitis (2), cholangitis (2), acute Hepatitis B (1) acute Hepatitis C (1), Rickettsia hepatitis (1), Cytomegalovirus hepatitis (1), Coxiella Burnetti hepatitis (1), choledocholithiasis (1) and sphincter Oddi hypertony (1).

The etiology of the elevation of aminotransferases varied according to age: patients with hepatocellular disorders were younger (mean = 50.3 years, standard deviation = 19.9), while neoplasias and pancreaticobiliary diseases were more common in older patients (mean = 62.5 years, standard deviation = 17.7; mean = 69.0 years, standard deviation = 17.2, respectively) and ischemic hepatitis occurred in the elderly (average 73.4 years, standard deviation = 15.6).

Cholestasis was more frequent in pancreaticobiliary diseases (p < 0.001).

Ischemic hepatitis tended to be associated with higher values of GPT (mean 1045,6U/L), following hepatocellu-lar disorders (mean 930,6U/L). More modest increases of GPT levels were observed in pancreaticobiliary disorders (average 699,6U/L).

DiscussionOur study showed that, contrary to what it is described in the literature,5,7,8,16,17 pancreaticobiliary lithiasis is the most common cause of marked increase of aminotrans-ferases, while accounting for 39.3% of the diagnoses. Some previous studies9,18 reinforce our results. Nonetheless, the underlying mechanism to explain the hepatocellular pattern in lithiasic pathology is not yet properly understood. It is speculated that bile duct obstruction by calculi im-paction conditions a rapid expansion of bile canaliculi with bile stasis, increasing its pressure and/or associating with local infection, affecting the surrounding hepatocytes and predisposing to hepatocellular necrosis and increased aminotransferases.12,18 Often enough, this increase tends to occur early on and is soon reduced after calculi disimpac-tion. Hepatocellular necrosis does not release, however, large amounts of alkaline phosphatase into the circulation and high levels of this enzyme, associated to cholestatic pattern, can probably be considered the result of a combination of impaired sinusoids and regurgitation through increased synthesis of bile canaliculi, which occur at a slower rate. For this reason, we are able to justify the pattern of predominant hepatocellular (and the absence of the pattern of typical cholestatic) in some cases of biliary obstruction.12,18

The rate of each etiology found in our study is consistent with the current reality observed in most emergency rooms. On one hand, the prevalence of lithiasic pathology, along with obesity and metabolic syndrome rates, has increased in recent years. It is estimated that at least 10% of adults in developed countries have cholesterol calculi.19 Shaffer19 also suggests that lithiasic pathology is the most common motive for hospital admissions related to gastrointestinal diseases. Associated to its frequency, are the high costs involved in its management, estimated at 6.5 billion dollars a year in the United States.19 On the other hand, the prevalence of liver diseases, including viral infections, has gradually started to decrease due to vaccination programs and social awareness campaigns.20

This study also highlighted that delaying early surgical intervention after the first episode of clinical manifestation of gallstones can lead to recurrence (32%) and further complications (70.8%).

In the absence of an immediate justification for hyper-transaminemia, it may be useful to take into account some epidemiological data and deepen the etiologic study. On one hand, female19 and elderly patients18 seem to be more prone to develop pancreaticobiliary diseases that are not always detected through ultrasonography and that require more sensitive diagnostic procedures. On the other hand, neoplasias are more prevalent in elderly patients (20.5%) and young patients are often affected by treatable etiologies, such as infectious hepatitis (9.4%).

The study was limited by:

- •

Its retrospective and descriptive design.

- •

The fact that aminotransferases do not comprise true indicators of liver function and that their origin isn’t exclusively hepatic.

- •

Unavailability of laboratorial monitoring (namely for aminotransferases progression).

All of these factors might have contributed to a limitation of the data analysis. Aiming to overcome these restraints, all other available analytical, clinical, imaging and histological available data were investigated in an attempt to confirm the final diagnosis. Additionally, as it is stated in the methods and results sections, we excluded all patients with insufficient information in order to provide a clear diagnosis for the hypertransaminemia. We should also account for the limiting factor related to the cut-off point for “marked elevation of aminotransferases”, which is not yet standardized. Even though a higher cut-off decreases the sample size, thus making it difficult to generalize the results, it may also increase the possibility of undiagnosed cases with lower aminotransferases values.

ConclusionPancreaticobiliary lithiasis is the main cause of marked hypertransaminemia. Hence, it must always be considered in the differential diagnosis in order to improve the prognosis of these patients. Not performing cholecystectomy early on after the first episode of biliary obstruction may lead to cases of recurrence.

Abbreviations- •

CHUC: Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coim-bra.

- •

GOT: glutamic oxalacetic transaminase.

- •

GPT: glutamic pyruvic transaminase.

None declared.