Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a major sign of severe liver disease and the impact of associated bacterial infectious should be better evaluated. A retrospective cohort of 333 patients with cirrhosis and HE was analyzed in three periods of time, from 1984 to 1998. Variance analysis, Wilcoxon, Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used for statistical comparisons. Prevalence of bacterial infections decreased along the time (p = 0.0029). Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis -SBP- (37%) and urinary tract infection (30%) were the more frequent types of bacterial infections. Early death was significantly higher in HE with infection (46,47%) and the calculated RR was 2.047. Prognosis was worse in septicemia (79%) and respiratory tract infection (50%) and better in urinary tract infection (27%). SBP lethality was reduced from 70% to 38% (p = 0.062). In conclusion, lower prevalence of bacterial infections, in severe liver disease, was achieved in the last decade, but short-term prognosis remains bad, varying according to the type of bacterial infection.

Bacterial infection in cirrhosis often leads to hospital admissions and high mortality rates. Besides that, infections in patients with liver disease have a different clinical presentation, with few or no symptoms, requiring an active search, specially for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and urinary tract infections.1,2 On the other hand, hepatic encephalopathy (HE) a frequent and severe complication of cirrhosis, can be even more worrisome when associated with bacterial infections. Survival of cirrhotic patients with HE has been investigated, confirming bacterial infections as a main cause of death, although types of infection and their relations to lethality have not been submitted to a thorough analysis.3

The pathogenesis of infections in cirrhosis is mainly related to the altered host defenses, including: decreased function of macrophages, neutrophils, monocytes and disturbed phagocytosis with less destruction of bacteriae. Both humoral and cellular immunity are usually altered, associated with impaired motility of the small intestines and bacterial overgrowth.4-6 Extrinsic factors such as alcoholism, malnutrition, gastro-intestinal hemorrhage, invasive diagnostic/therapeutic procedures and altered permeability of intestinal mucosa, also predispose to bacterial infections.7,8

During the last two decades we have published a series of papers dealing with both bacterial infections1,9 and the treatment of Hepatic Encephalopathy,10,11 which enables us to re-visit these data, collected within very strict methodological criteria. The main objective was to analyze in severe liver disease, namely cirrhosis associated with hepatic encephalopathy, both prevalence and outcome of different types of infection, occurring in three periods of time.

Patients and methodsThe medical records from patients with cirrhosis, admitted due to HE or developing HE during the hospitalization at Heliópolis Hospital from 1984 to 1998 were reviewed, representing a retrospective cohort for the study of prevalence and outcome of bacterial infections. Most part of these patients had been included in previous publications,1,9,11 and three different periods of time could be characterized, namely 1984-1989, 1990-1993, 1994-1999, corresponding to the study period of different protocols. Inclusion criteria was a diagnosis of both cirrhosis and HE, whereas exclusion criteria were chronic HE associated with surgical shunt and diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Diagnosis of cirrhosis was made either by hepatic biopsy or by clinical and laboratorial data.12 On admission, all patients were submitted to clinical evaluation for the presence of fever, jaundice, anemia, ascites, gastrointestinal hemorrhage and encephalopathy. Laboratory tests included liver enzymes, bilirubins, protein eletrophoresis, prothrombin time, as well as serological markers for hepatitis viruses: HBsAg and anti-HCV (ELISA-kits, Abbott).

Hepatic Encephalopathy was defined a spectrum of neuropsychiatric abnormalities seen in patients with liver dysfunction after exclusion of other known brain disease. 13 According to the Consensus of the Working Party our cases were of overt HE associated with cirrhosis and portal hypertension, or type C.13

For evaluation of bacterial infections a protocol was followed. Blood samples for hemoculture and one sample for urine culture were routinely collected in the first 48 hours of admission. Blood as well as ascitic fluid, if present, were collected into blood culture bottles at bedside (Runyon´s procedure), and incubated for 24 h at 37o.

Diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis was made when the ascitic fluid presented more than 250 neutrophils/ mm3 with clinical signs of SBP or more than 500, irrespective of the result of a positive culture. The possibility of a secondary peritonial infection was always excluded and antimicrobial prophylaxis of SBP had not been indicated for patients included in this study. Respiratory tract infection was diagnosed by clinical and radiological criteria. Urinary infections were mainly diagnosed by the isolation of bacteria in the urine culture above 106/mm3, but also by clinical symptoms and leukocyturia according to Suarez and Pajares. 14 For the diagnosis of sepsis, besides the isolation of bacteria in the blood stream, clinical symptoms and signs of severe systemic infection were present, characterizing SIRS (Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome”. Other types of infection were diagnosed by specific methods in accordance with the infectious process.

The parameters submitted to comparative analyzes, in the three consecutive periods of time were: sex, age, etiology of cirrhosis and the prognostic classification of Child-Pugh.15 Although other precipitating factors of HE were collected in each patient, this article will focus only on bacterial infections. All types of bacterial infections occurring in patients with HE were included, not necessarily preceding the neuropsyquiatric disorder, but sometimes following and complicating it. Besides comparing HE patients with and without infection, the site of the infectious process, its prevalence and the outcome of the patient, in terms of mortality during hospitalization or survival, were also analyzed.

Wilcoxon, Chi-Square and Fisher´s exact test were used for statistical comparisons and a p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. Estimates of the relative risk (RR) and maximum–likelihood analysis of variance were also performed to evaluate differences among groups and in survival along the time.

ResultsDemographic data regarding sex, age, etiology of cirrhosis and Child-Pugh classification did not show statistical differences among infected and non-infected patients with cirrhosis and HE, in the three periods of study (Table I) On the other hand, the prevalence of bacterial infections decreased significantly (p = 0.002) along the time, as shown in table II When different types of infections were analyzed their relative proportions have varied, but with no statistical differences (p = 0.123), depicted in table III Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis was the most frequent type of infection, followed closely by the urinary tract infection.

Demographic data of 333 patients with H.E. in three periods of study.

| 1984-1989 n = 124 | 1990-1993 n = 111 | 1994-1998 n = 98 | “p” | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Median | 54 | 53 | 52 | 0.239 |

| Extrems | 14-86 | 23-81 | 29-78 | ||

| Sex | Male | 101(81.9%) | 86 (77.5%) | 86 (87.7%) | 0.153 |

| Female | 23 (18.5%) | 25 (22.56%) | 12 (12.23%) | ||

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | 87 (70%) | 90 (81.1%) | 72 (73.5%) | 0.147 | |

| Child Pugh classification | |||||

| A | 0.8% | 0.6% | 0 | ||

| B | 22.0% | 9.5% | 13.9% | 0.480 | |

| C | 77.2% | 89.8% | 86.1% | ||

Prevalence of the different types of bacterial infection in three periods of study.

| SBP | UTI | SEP | RTI | DERM | Others | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1984-1989 | 34 44.74% | 23 30.26% | 4 5.26% | 8 10.53% | 4 5.26% | 3 3.95% | 76 |

| 1990-1993 | 13 25% | 14 26.92% | 11 21.15% | 10 19.23% | 4 7.69% | 0 0.00% | 52 |

| 1994-1998 | 16 38.10% | 14 33.33% | 4 9.52% | 4 9.52% | 2 4.76% | 2 4.76% | 42 |

| Total | 63 | 51 | 19 | 22 | 10 | 5 | 170 |

| p = 0.123 |

SBP – Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

UTI – Urinary tract infection

SEP – Septicemia

RTI – Respiratory tract infection

DERM – Dermatological infection

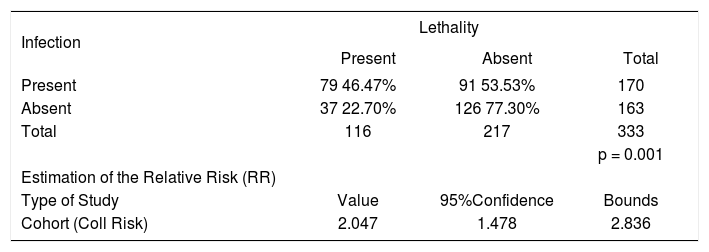

When short-term prognosis, meaning lethality during hospitalization was analyzed, there were 79 deaths (46.5%) among the 170 infected patients and 37 (22.7%) in the group of HE patients without infection. This difference was statistically significant (p < 0.001), as shown in table 4 and the calculated risk factor (RR) was 2.047 with 95% confidence intervals of 1.478-2.836. The statistical analysis has also shown a significant interaction between infection and lethality. Probabilities of death in the groups have dropped from 0.5347 to 0.2291 and from 0.4285 to 0.1071, in the first and third periods, according to the status of being or not infected. In table 5 lethality according to the type of infection is depicted. We can ob-serve that lethality due to SBP dropped dramatically from near 70% to less than 40%, although statistical significance was not reached (p = 0.062). For all other types of infection the outcome was similar during the whole period of the study and it was possible to demonstrate that sepsis (mortality of 79%) and pulmonary infection (mortality of 50%) carried the worst prognosis, whereas UTI (mortality of 27%) presented the best prognosis.

Comparison of lethality in H.E. patients with and without infection.

| Infection | Lethality | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Absent | Total | |

| Present | 79 46.47% | 91 53.53% | 170 |

| Absent | 37 22.70% | 126 77.30% | 163 |

| Total | 116 | 217 | 333 |

| p = 0.001 | |||

| Estimation of the Relative Risk (RR) | |||

| Type of Study | Value | 95%Confidence | Bounds |

| Cohort (Coll Risk) | 2.047 | 1.478 | 2.836 |

Comparisons of lethality in three periods of the study, according to the type of bacterial infection.

| 1984-1989 | 1990-1993 | 1994-1998 | Total | "p" | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of Infection | ||||||

| N | 34 | 13 | 16 | 63 | ||

| SBP | Death | 23 | 5 | 6 | 34 | 0.062 |

| % | 67.6 | 38.4 | 37.5 | 54 | ||

| UTI | N | 23 | 14 | 14 | 51 | |

| Death | 9 | 1 | 4 | 14 | 0.146 | |

| % | 39.1 | 7.1 | 28.6 | 27.4 | ||

| N | 8 | 10 | 4 | 22 | ||

| RTI | Death | 4 | 5 | 2 | 12 | 1.00 |

| % | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50.0 | 50 | ||

| N | 4 | 11 | 4 | 19 | ||

| SEP | Death | 4 | 8 | 3 | 15 | 0.773 |

| % | 100 | 72.7 | 75.0 | 79 |

SBP – Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis

UTI – Urinary tract infection

RTI – Respiratory tract infection

SEP – Septicemia

The results of the present study indicate that the prevalence of bacterial infections, among cirrhotic patients with HE, has decreased in the last decades but is still very high. It is well known that the severity of liver dysfunction found in cirrhosis leads to altered host defenses. The presence of HE in the course of cirrhosis is surely a marker of severe hepatic dysfunction that may correlate with high prevalence of bacterial infections.

Our data, in terms of severity of liver disease, is comparable to a recent study of the prognostic significance of hepatic encephalopathy,3 where Child C patients accounted for 69% of their cases and we had from 77.2 to 89.8%, with no differences in the periods of time evaluated. It was interesting to notice that demographic characteristics of our patients, as sex, age, etiology of cirrhosis and severity of liver damage have not changed in the last two decades, despite the significant decrease of prevalence of bacterial infections. Along the time, means of diagnosis have improved, new techniques developed and early diagnosis was enhanced, specially for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.16 Although new antibiotics and bacterial resistance have been a continuous challenge in recent years,17,18 specific therapy for infections in patients with cirrhosis has generally improved.19,20 Cost-analysis has demonstrated that antibiotic prophylaxis for SBP is very cost-effective, when restricted to high risk groups.21 The prevalence of infection of the urinary tract was stable along the years, about 30% of all cases, whereas differences occurred for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, the most prevalent in two of the three periods. Urinary tract infection is the most frequent type of bacterial infection in cirrhosis, according to some authors,22 but not for others.1,2,8 According to this study both types of infection are equally prevalent.

It is worthwhile to comment on the two exclusion criteria of our study, namely porto-systemic encephalopathy and hepatocarcinoma. Shunt surgery for portal hypertension, almost abandoned in the last decade, is now considered a valid option.23 In fact, it continued to be performed for non-cirrhotic portal hypertension and in our experience with proximal and distal spleno-renal shunts for hepatosplenic schistosomiasis, both may lead to HE.24 Nevertheless, cases of bacterial infections are casual, not related to shunt-induced HE. Metabolic coma, on the other hand, may be related to hepatocarcinoma, motivating their exclusion, although prevalence of bacterial infections in cirrhosis with or without hepatocarcinoma has not shown differences in a large Japanese study.25

Although it is well known that survival of cirrhotic patients who have had an episode of HE will not be very long and they should be considered as candidates for liver transplantation, we were particularly interested in evaluating the short-term prognosis of these patients. Early death, during hospitalization, occurred in 22.7% of non-infected cirrhotics with HE and in 45.47% of the infected ones (p = 0.001). The mechanisms by which bacterial infections deteriorates hepatic function are of special interest nowadays. It is speculated that it involves circulatory dysfunction.26 The release of endotoxins as well as the induction of vasoconstrictor factors as endothelin, prostacyclin and nitric oxide may play a major role, not only in the general circulatory function but specially in the renal and hepatic hemodynamics. According to some authors bacterial infections in patients with variceal hemorrhage may trigger more bleeding,27 being associated with failure to control variceal bleeding.28 Renal insufficiency, either progressive or transient is frequently observed following bacterial infections, specially spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.29,30

Gathering the data of these 15 years of experience, it was also possible to distinguish different prognosis according to the type of infection. As expected, urinary tract infection had the lower mortality rates, around 25%, whereas sepsis carried the worst prognosis, with 80% mortality, similar to what is found in acute hepatic insufficiency. 31 Considering that half of the patients with respiratory tract infections died during hospitalization, this type of infection is also severe. A reduction of lethality was detected only for SBP, most probably due to early diagnosis and treatment of this condition with new antibiotics, particularly cephalosporines of third generation.

In conclusion, the very high prevalence of bacterial infections associated with HE has diminished along the time. Although multiple factors can be involved in the prognosis of hepatic encephalopathy, bacterial infection continues to be a very serious and life-threatening complication. Different types of infection carry different short-term prognosis. In the last decade, the early diagnosis and adequate management of SPB has improved its survival rates.