Introduction and aim. Studies suggest that entecavir and lamivudine are useful as prophylactics against hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in patients undergoing chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy, but which drug is more effective is unclear. Here we meta-analyzed available evidence on relative efficacy of prophylactic entecavir or lamivudine therapy in patients with chronic or resolved hepatitis B infection who were undergoing chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy.

Material and methods. Two reviewers searched PubMed, EMBASE and Google Scholar as well as reference lists in relevant articles to find studies published between January 2005 and May 2015 that met inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data on HBV reactivation, HBV-related hepatitis and all-cause mortality were extracted from the studies and meta-analyzed.

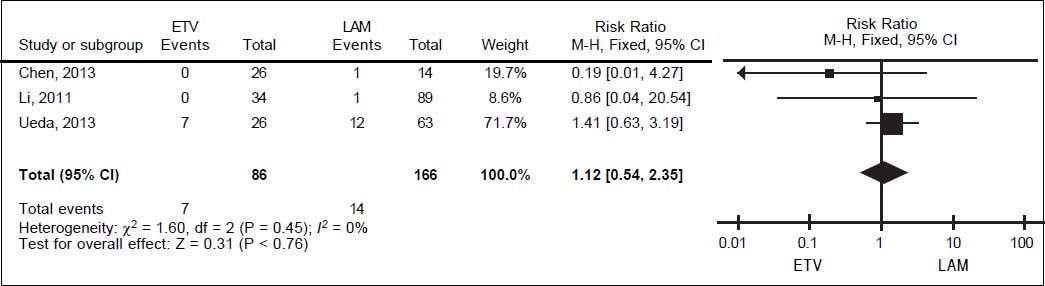

Results. A total of eight studies involving 593 patients were included in the meta-analysis, which was performed using a fixed-effect model since no significant heterogeneity was found. Entecavir was associated with significantly lower risk of HBV reactivation than lamivudine (RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.52) as well as lower risk of HBV-related hepatitis (RR 0.11, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.40). The two drugs were associated with similar risk of all-cause mortality (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.54 to 2.35). Egger’s test suggested no significant publication bias in the meta-analysis.

Conclusions. The available evidence suggests that entecavir is more effective than lamivudine for preventing HBV reactivation and HBV-related hepatitis in patients with chronic or resolved HBV infection who are undergoing chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy.

Over 350 million people worldwide suffer from chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.1 Such individuals can suffer HBV reactivation when they are exposed to immunosuppressive agents, such as during chemotherapy, steroid therapy, organ transplantation, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation or therapy involving cytotoxic drugs. During HBV reactivation, HBV DNA levels increase by ≥ 10-fold over baseline levels (or show an absolute increase of >105 copies/mL), leading to hepatitis. Reactivation can then lead to severe hepatitis, fulminant liver failure and even death in 4-89% of cases.2–4 As many as 60% of cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy can suffer HBV reactivation,5–7 with lymphoma patients at the greatest risk. Indeed, most lymphoma patients (68-71%) suffer delays, interruptions or early termination of chemotherapy because of HBV reactivation.8 Reactivation even occurs in 225% of lymphoma patients who are negative for HBV surface antigen (HBsAg).9,10 Immunosuppressive treatment of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease can also trigger HBV reactivation.11–12

European guidelines13 recommend that HBsAg-positive candidates for chemotherapy and immunosuppressive therapy receive prophylactic antiviral therapy to prevent HBV reactivation. They also recommend careful monitoring of serum HBV DNA levels during chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy of patients with resolved HBV infection, defined as those who are negative for HBsAg but positive for HBV core antibody (anti-HBc). Prophylactic lamivudine therapy is used most frequently to prevent HBV reactivation and is recommended in official guidelines.14–17 Lamivudine has been shown to be safe and effective at reducing the incidence of HBV reactivation,14,18,19 but prolonged use is strongly associated with the emergence of HBV drug resistance.13 Prophylactic entecavir has shown promise for reducing HBV reactivation without triggering high rates of viral resistance,20–22 but relatively few studies have examined this drug. Some studies have compared the two drugs head-to-head, but the results have been contradictory, with some studies suggesting that the drugs are comparable and others suggesting that entecavirismore effective.

In order to gain comprehensive insights into how the two drugs compare in safety and efficacy, we systematically reviewed the literature on prophylactic lamivudine or entecavir therapy for patients with chronic HBV infection (HBsAg-positive) or resolved HBV infection (HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc-positive) during or following chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to compare each drug’s ability to prevent HBV reactivation and reduce the risk of HBV-related hepatitis and all-cause mortality.

Material and MethodsSearch strategyTwo authors (CY, HYZ) searched PubMed, EM-BASEand Google Scholar to identify relevant studies published between January 2005 and May 2015, using the following search terms: ‘hepatitis B OR hepatitis B virus’, ‘entecavir’, ‘lamivudine’, ‘nucleoside analogue’, ‘reactivation OR recurrence’. Search results were not limited to any language or geographic region. Reference lists in selected articles and relevant review articles were searched manually to identify additional studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaStudies were included if they involved:

- •

A case-control or cohort study, whether prospective or retrospective, or a randomized controlled trial (RCT).

- •

Patients who were HBsAg-positive or with resolved HBV infection (HBsAg-negative, anti-HBc-positive).

- •

Patients who received chemotherapyor other immunosuppressive therapies due to organ transplantation, hematological disease, cancer or other underlying immune disease.

- •

Patients who received prophylactic entecavir or lamivudine therapy.

- •

HBV reactivation defined as an increase in HBV DNA levels ≥ 10-fold over baseline levels or as an absolute increase of > 105 copies/mL in the absence of other systemic infection.23

Studies were excluded if they were case reports or review articles, or if they reported in sufficient data to assess outcomes.

Data extractionTwo authors (CY, HYZ) independently evaluated and extracted data from studies using a predefined, standardized protocol. Data were extracted on study authors, journal of publication, country of study, study period, study design, underlying disease, therapy received, prophylactic use of entecavir or lamivudine, and follow-up. Data were collected on the primary outcome, which was the numbers of individuals on either entecavir or lamivudine therapy who experienced or did not experience HBV reactivation. Data were also collected on the secondary outcomes of HBV-related hepatitis, hepatitis-related interruption of chemotherapy, all-cause mortality and adverse events. Disagreements about extracted data were resolved through discussion.

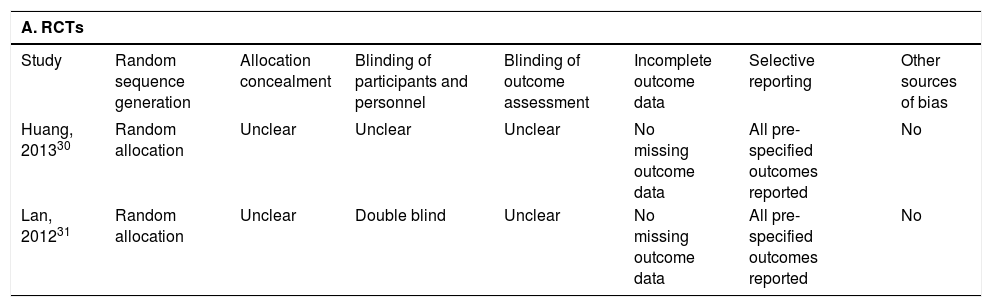

Quality assessmentThe quality of included RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias,24 while the quality of case-control and cohort studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS).25 We developed an NOS-based scale for scoring the studies. The scale ranged from 0 to 9 points; studies of low quality were given NOS scores of 1-3; studies of intermediate quality, 4-6; and studies of high quality, 7-9.

Statistical analysisData were meta-analyzed using RevMan 5.2.7 (Cochrane Collaboration). Pooled relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for all outcomes. Statistical heterogeneity between studies was assessed either using a chi-squared test in which P < 0.10 was taken as the threshold of significant heterogeneity, or using the I2 value, with I2 > 50% considered evidence of heterogeneity. The Mantel-Haenszel fixed-effect model was used to report pooled outcomes if heterogeneity was not significant; otherwise, a random-effect model was used. Data on the primary outcome were subjected to subgroup meta-analysis according to patients’ underlying disease and the study design. Risk of publication bias was assessed using Egger’s test as implemented in STATA 11.2.26

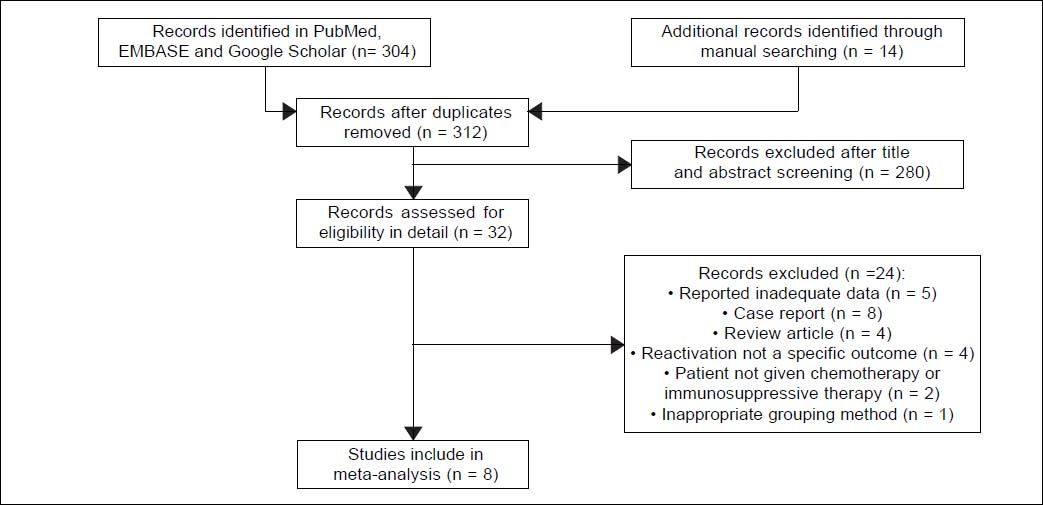

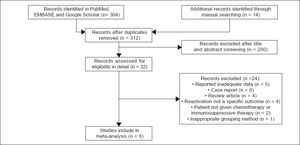

ResultsStudy selectionAutomated and manual searching identified 312 nonduplicate records, 280 of which were excluded based on title and abstract screening. The remaining 32 records were read in detail, and eight were finally included in the meta-analysis (Figure 1).27–34 Seven of these studies were published in full, while one was published only as an abstract.

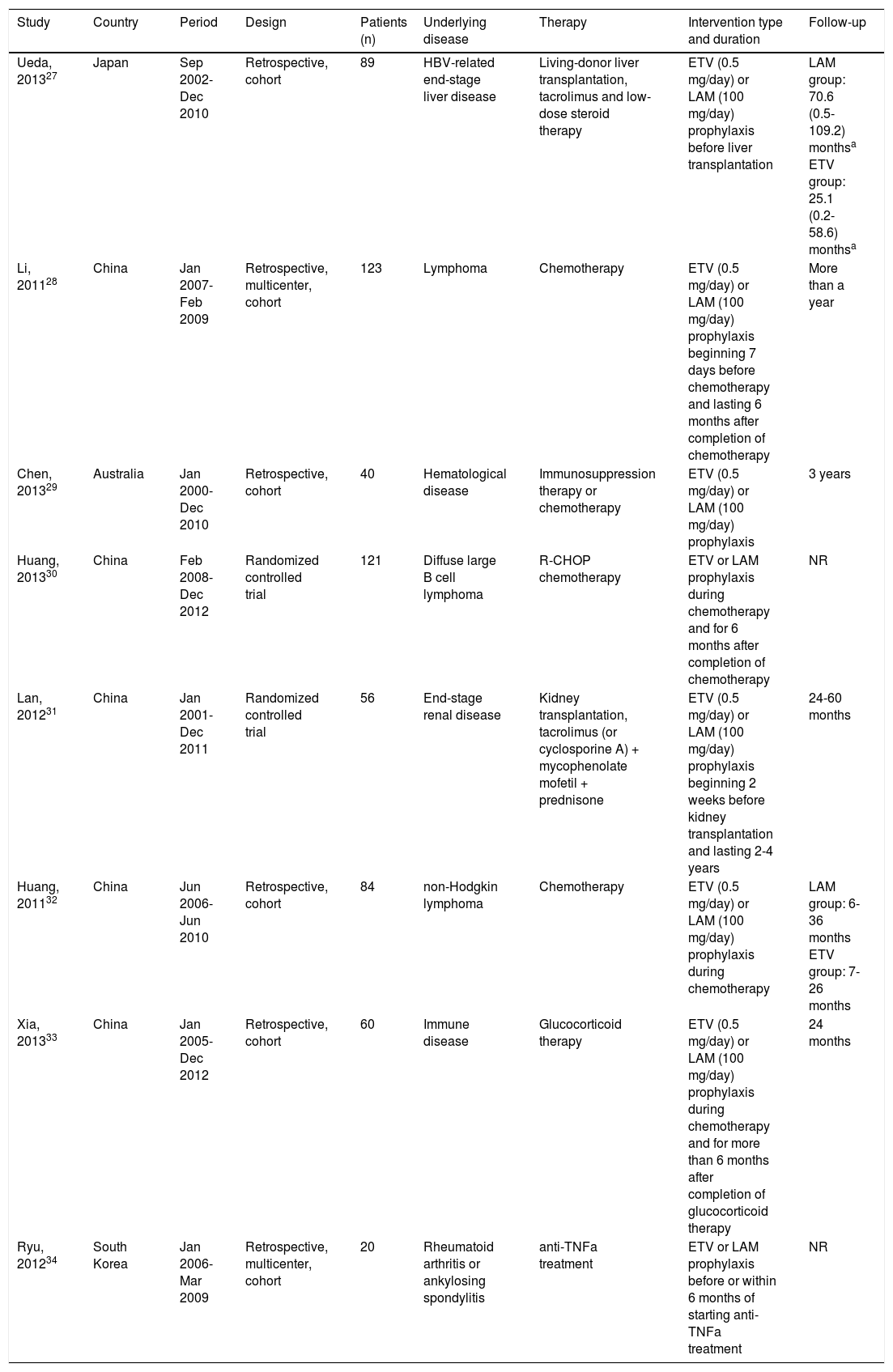

Study characteristicsThe eight studies in the systematic review included two RCTs and six retrospective cohort studies covering a total of 593 patients from China (five studies), Japan (one study), South Korea (one study) and Australia (one study) (Table 1). Four of the six cohort studies were performed at single centers. Patients in the studies had the following underlying diseases: hematological disease (lymphoma or others), immune disease, HBV-related end-stage liver disease, endstage renal disease, rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis. All patients received chemotherapy, glucocorticoid therapy or other immunosuppressive therapies.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Study | Country | Period | Design | Patients (n) | Underlying disease | Therapy | Intervention type and duration | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ueda, 201327 | Japan | Sep 2002-Dec 2010 | Retrospective, cohort | 89 | HBV-related end-stage liver disease | Living-donor liver transplantation, tacrolimus and low-dose steroid therapy | ETV (0.5 mg/day) or LAM (100 mg/day) prophylaxis before liver transplantation | LAM group: 70.6 (0.5-109.2) monthsa ETV group: 25.1 (0.2-58.6) monthsa |

| Li, 201128 | China | Jan 2007-Feb 2009 | Retrospective, multicenter, cohort | 123 | Lymphoma | Chemotherapy | ETV (0.5 mg/day) or LAM (100 mg/day) prophylaxis beginning 7 days before chemotherapy and lasting 6 months after completion of chemotherapy | More than a year |

| Chen, 201329 | Australia | Jan 2000-Dec 2010 | Retrospective, cohort | 40 | Hematological disease | Immunosuppression therapy or chemotherapy | ETV (0.5 mg/day) or LAM (100 mg/day) prophylaxis | 3 years |

| Huang, 201330 | China | Feb 2008-Dec 2012 | Randomized controlled trial | 121 | Diffuse large В cell lymphoma | R-CHOP chemotherapy | ETV or LAM prophylaxis during chemotherapy and for 6 months after completion of chemotherapy | NR |

| Lan, 201231 | China | Jan 2001-Dec 2011 | Randomized controlled trial | 56 | End-stage renal disease | Kidney transplantation, tacrolimus (or cyclosporine A) + mycophenolate mofetil + prednisone | ETV (0.5 mg/day) or LAM (100 mg/day) prophylaxis beginning 2 weeks before kidney transplantation and lasting 2-4 years | 24-60 months |

| Huang, 201132 | China | Jun 2006-Jun 2010 | Retrospective, cohort | 84 | non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Chemotherapy | ETV (0.5 mg/day) or LAM (100 mg/day) prophylaxis during chemotherapy | LAM group: 6-36 months ETV group: 7-26 months |

| Xia, 201333 | China | Jan 2005-Dec 2012 | Retrospective, cohort | 60 | Immune disease | Glucocorticoid therapy | ETV (0.5 mg/day) or LAM (100 mg/day) prophylaxis during chemotherapy and for more than 6 months after completion of glucocorticoid therapy | 24 months |

| Ryu, 201234 | South Korea | Jan 2006-Mar 2009 | Retrospective, multicenter, cohort | 20 | Rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis | anti-TNFa treatment | ETV or LAM prophylaxis before or within 6 months of starting anti-TNFa treatment | NR |

Qualitative assessment of the information reported in the two RCTs showed that neither had any missing out-come data: both RCTsreported all pre-specified outcomes, and one of them was double-blind (Table 2). Quantitative NOS scoring of the six cohort studies showed an average score of 8 (range, 6-9), with five studies considered of high quality and one of intermediate quality (Table 2). Only one cohort study33 failed to compare baseline characteristics in the entecavir and lamivudine groups. Another study27 showed that the two groups of patients did not differ significantly at baseline in terms of age, sex, primary disease or serological HBV markers, but that the entecavir group had significantly lower baseline serum HBV DNA levels than the lamivudine group. A third study29 showed that the proportion of patients with elevated ALT levels and detectable HBV DNA at baseline was higher in the lamivudine group. The remaining three studies28,32,34 reported that both patient groups were comparable in terms of measured clinicopathological variables.

Quality assessment of included studies.

| A. RCTs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Other sources of bias |

| Huang, 201330 | Random allocation | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | No missing outcome data | All pre-specified outcomes reported | No |

| Lan, 201231 | Random allocation | Unclear | Double blind | Unclear | No missing outcome data | All pre-specified outcomes reported | No |

| B. Cohort studies | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection rating (points) | Comparability rating (points) | Outcome rating (points) | |||||||

| Study | Representativeness of exposed cohort | Selection of non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Outcome of interest absent at start of study | Controls for important factor or additional factor | Assessment of outcome | Follow-up A long enough for outcomes to occur | dequacy of follow-up of cohorts | Total points |

| Ueda, 201327 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Li, 201128 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 |

| Chen, 201329 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Huang, 201132 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Xia, 201333 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Ryu, 201234 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

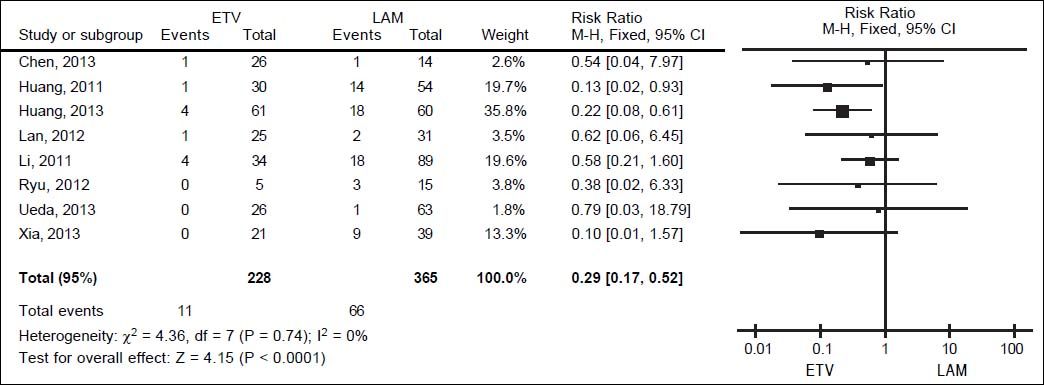

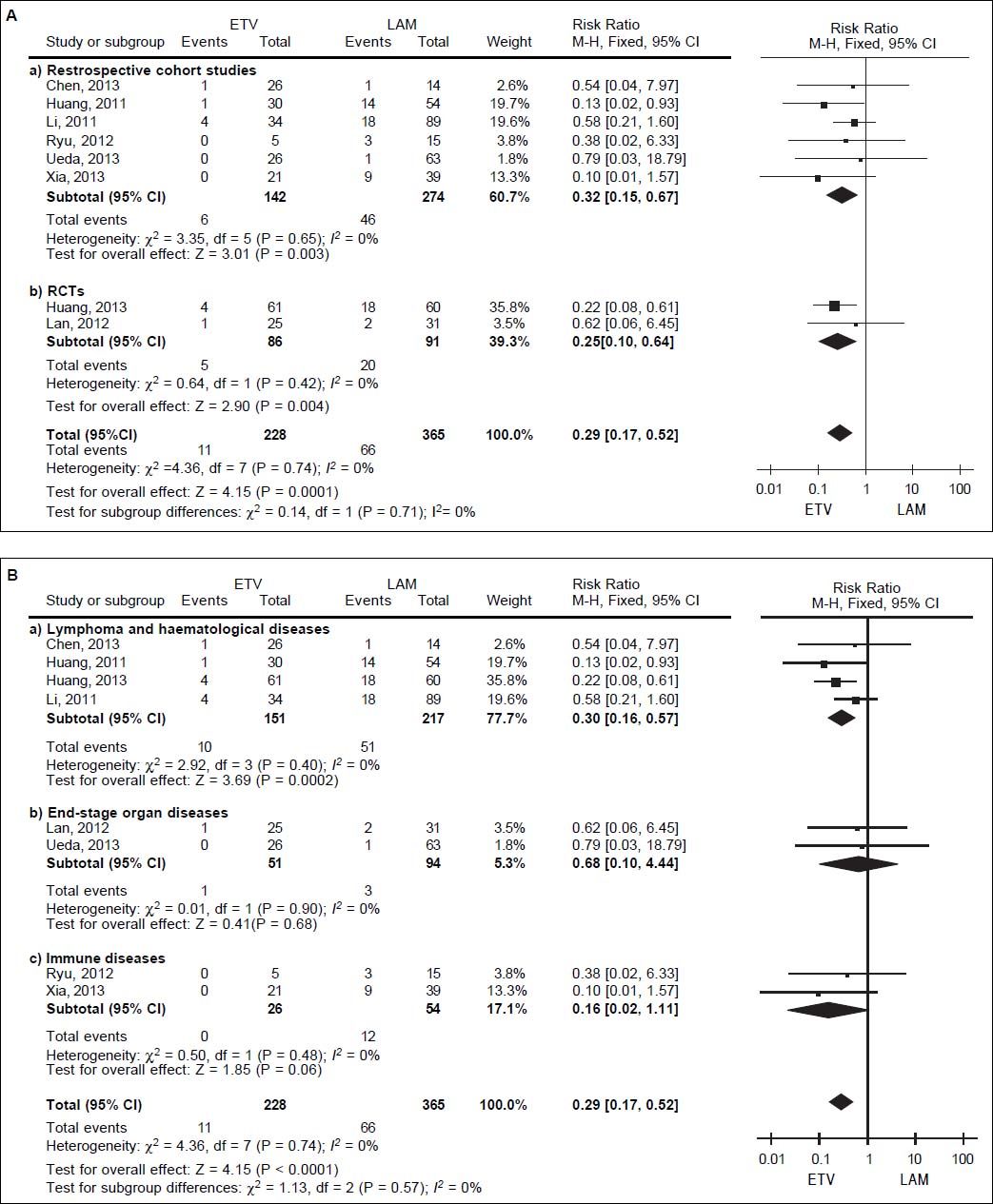

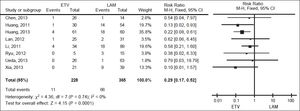

We pooled data on HBV reactivation in 593 patients receiving either prophylactic entecavir or lamivudine therapy in all eight studies identified in the systematic review (Figure 2). Total incidence of HBV reactivation was 4.82% in the entecavir group and 18.08% in the lamivudine group. Based on the lack of significant heterogeneity in the pooled data (I2 = 0%, P = 0.74), fixed-effect meta-analysis was performed, which indicated significantly lower risk of HBV reactivation with entecavir than with lamivudine (RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.52, P < 0.001).This result was robust to the study design, since it remained unchanged when the meta-analysis was restricted only to retrospective cohort studies (RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.67, P < 0.01) or only to RCTs (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.64, P < 0.01) (Figure 3A).

However, this result differed depending on the patients’ underlying disease (Figure 3B). When the metaanalysis was restricted to patients with lymphoma or other hematological disease (n = 368), entecavir again emerged as more effective at reducing risk of HBV reactivation (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.57, P < 0.001). In contrast, the two drugs were associated with similar risk of reactivation among patients with end-stage organ disease treated byorgan transplantation (n = 145; RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.10 to 4.44, P = 0.68), as well as among patients with immune disease (n = 80; RR 0.16, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.11, P = 0.06).

Secondary outcomesWe had planned to extract data on the following four secondary outcomes: HBV-related hepatitis, hepatitis-related chemotherapy interruption, all-cause mortality and adverse events. However, only two studies reported on hepatitis-related interruption of chemotherapy, while only one reported data on adverse events.Therefore only data on HBV-related hepatitis and all-cause mortality could be meta-analyzed.

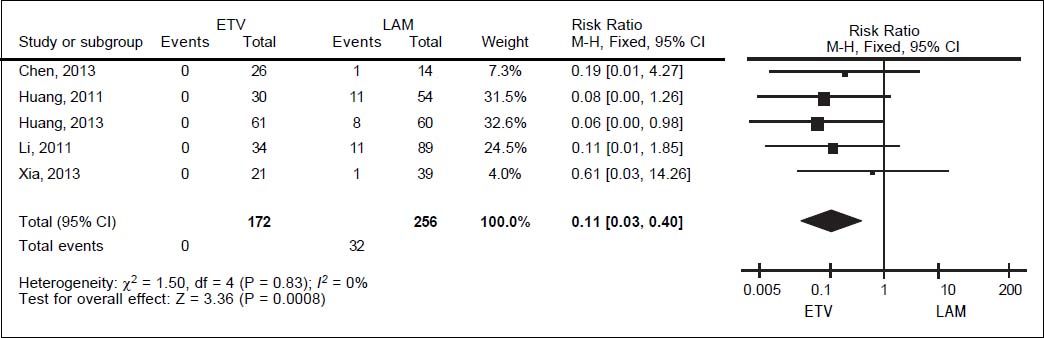

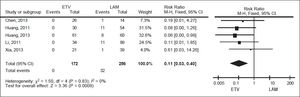

For HBV-related hepatitis, data on 428 patients in five studies were meta-analyzed using a fixed-effect model, since they showed no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.83; Figure 4). Total incidence of HBV-related hepatitis was 0% in the entecavir group and 12.50% in the lamivudine group. The corresponding pooled RR for entecavir relative to lamivudine was 0.11 (95% CI 0.03 to 0.40, P < 0.001).

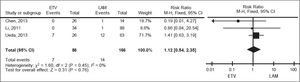

For all-cause mortality, data on 252 patients from three studies were also meta-analyzed using a fixed-effect model, since they showed no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = 0.45; Figure 5). All-cause mortality rates were 8.14% in the entecavir group and 8.43% in the lamivudine group.The corresponding pooled RR for entecavir relative to lamivudinewas 1.12 (95% CI 0.54 to 2.35, P = 0.76).

Publication biasEgger’s test was used to assess risk of publication bias in the meta-analyses of primary and secondary outcomes. The test showed no significant risk of bias in the case of HBV reactivation (t = 0.17, P > |t| = 0.873), HBV-related hepatitis (t = 2.17, P > |t| = 0.119) or all-cause mortality (t = -2.44, P > |t| = 0.247).

DiscussionHBV reactivation continues to be a major concern for HBV carriers around the world who are receiving chemotherapy or immuno suppressive therapy. Although lamivudine is widely used to reduce the risk of reactivation, lamivudine monotherapy frequently leads to viral resistance, worsening patient prognosis.35 Entecavir has emerged as a potent alternative to lamivudine that is not associated with strong resistance, but its safety and efficacy have not been extensively analyzed, particularly in direct comparison to lamivudine. Ourstudy meta-analyzed available evidence comparing the two drugs and found entecavir to be more effective than lamivudine for preventing HBV reactivation and HBV-related hepatitis in patients with chronic or resolved HBV infection who were undergoing chemotherapy or immuno suppressive therapy.

Prophylactic lamivudine therapy rapidly suppresses HBV replication, reducing the incidence of HBV reactivation and improving survival.36 Nevertheless, entecavirshows several advantages over lamivudine: it appears to suppress HBV DNA replication more quickly and to a greater extent,37 and it is associated with much lower viral breakthrough due to resistance, even over longer treatment courses.38 Several case reports have found prophylactic entecavir therapy to be effective for preventing HBV reactivation in patients who undergocadaveric renal transplantation39 or treatment for lymphoma,35,40–42 hematological malignancies,22or progressive osteomyelo fibrosis.43 A recent RCT further showed that entecavir can significantly reduce the risk of HBV reactivation in patients with resolved HBV infection who are undergoing rituximabbased chemotherapy.20 The present meta-analysis and recent RCTs support the notion that while both prophylactic lamivudine and entecavir are effective against HBV reactivation inpatients on chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy,14,18,20 entecavir may be superior. In this way, our meta-analysis does not agree with some individual comparative studies showing entecavir and lamivudine to be similarly effectiveat reducing risk of HBV reactivation.27–29,31,33,34 One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that lower statistical power in the individual studies failed to capture the efficacy difference.

We assessed whether our meta-analysis results were robust to study design, since only some of the included studies were RCTs. Our results suggest that entecavir is more effective than lamivudine at reducing risk of reactivation, regardless of the type of study. We also assessed the robustness of our findings based on patients’ underlying disease, given that patients with different diseases can present with quite different clinical histories, therapies and prognoses, all of which can substantially increase heterogeneity in the meta-analysis. In addition, certain therapies are associated with greater risk of HBV reactivation than others. Anthracycline and steroids are recognized as risk factors for reactivation; steroids enhance HBV gene expression and increase risk of reactivation by binding to the glucocorticoid response element in the viral genome.6 Rituximab and alemtuzumab induce persistent B- and T-cell depletion, leading to immune dysfunction and HBV reactivation.44,45 Our meta-analysis of patient subgroups with different underlying disease showed that entecavir was associated with significantly lower risk of HBV reactivation for patients with lymphoma or other hematological disease. In contrast, the two drugs were associated with similar risk of reactivation among patients with end-stage organ disease treated by organ transplantation, as well as among patients with immune disease.

The lack of clinical superiority of entecavir in the latter two groups of patients may reflect the much smaller size of these subgroups and correspondingly low statistical power. Alternatively, it may indicate that patients with lymphoma or other hematological disease have higher risk of HBV reactivation than those with end-stage organ disease or immune disease, and that entecavir may be more effective than lamivudine at suppressing HBV DNA replicationin patients with lymphoma or other hematological disease. Indeed, our meta-finding that HBV reactivation occurred in 61 of368 patients (16.58%) with lymphoma or other hematologic diseases, but in only 4 of 145 patients (2.76%) with end-stage organ diseases and 12 of 80 patients (15.00%) with immune diseaseis consistent with reports that HBV reactivation is most common among lymphoma patients undergoing chemotherapy and among patients who undergo hematopoietic stem cell transplantation after immunosuppressive therapy.44 The higher risk of HBV reactivation in lymphoma patients may reflect, in part, that many such patients receive rituximab or alemtuzumab therapy, which by itself increases the risk of HBV reactivation. Whatever the cause of the higher risk in these patients, entecavir may protect them more effectively than lamivudine from HBV reactivation. Future studies should examine this possibility in greater detail.

In addition to HBV reactivation, our meta-analysis suggests that entecavir is superior to lamivudine at reducing risk of HBV-related hepatitis in patients with various underlying diseases. To what extent this reflects differences in drug resistance in each patient group is unclear, since the doses for each drug cannot be compared directly, treatment periods varied substantially and none of the studies reported testing for resistance. We suggest that a major cause of HBV-related hepatitis in the included studies was immunemediated liver destruction in patients with high viral load.46 Previous findings that entecavir can reduce HBV DNA levels more quickly and to a greater extent than lamivudine suggest that it may be a more appropriate first-line therapy in patients at risk of HBV reactivation, since it effectively reduces risk of both reactivation and HBV-related hepatitis. In other words, the available evidence argues for expanding the primary indications of entecavir beyond its use as a rescue therapy in patients showing viral break through under lamivudine monotherapy.

The results of our meta-analysisare likely to be reliable because they are based on the largest sample to date among comparisons of prophylactic entecavir and lamivudine, and because no significant heterogeneity among studies or significant risk of publication bias was detected for any of the outcomes examined. At the same time, our results are limited in several important ways. First, we were unable to perform meta-analyses for interruption of chemotherapy due to hepatitis and adverse events because most of the included studies did not report the relevant data. Second, again for lack of reported data, we were unable to metaanalyze outcomes based on HBV DNA levels. This is an important analysis because 2012 guidelines from the European Association for the Study of the Liver call for lamivudine prophylaxis in patients with low HBV DNA levels and for entecavir or tenofovir in patients with high levels (followed by lamivudine when DNA levels become undetectable).13 Future studies should examine whether these guidelines are supported by clinical experience. Third, we could not perform subgroup analysis separately for HBsAgpositive patients and patients with resolved HBV infection because most studies did not report characteristics or outcomes separately for the two groups. This question should be examined in the future since it may help determine when entecavir is justified over lamivudine.

ConclusionOur meta-analysis suggests that entecaviris more effective than lamivudine at preventing HBVreactivation and HBV-related hepatitis in patients with chronic or resolved HBV infection who are on chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy.The clinical superiority of entecavir is especially marked in patients suffering from lymphoma or other hematological diseases. Entecavir may be justified-despite its higher cost-as an alternative firstline therapy for preventing HBV reactivation during or following chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy.

Abbreviations- •

anti-HBc: antibody against HBV core protein.

- •

ETV: entecavir.

- •

HBsAg: hepatitis B virus surface antigen.

- •

HBV: hepatitis B virus.

- •

LAM: lamivudine.

- •

NOS: Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

- •

NR: not reported.

- •

R-CHOP: combination therapy of rituximab with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone.

- •

RCT: randomized controlled trial.

- •

TNF: tumor necrosis factor.

This study was funded entirely by the Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing (grant CSTC2012jjA10052).

Author ContributionsChun Yang and Hong-yu Zhou designed the study and wrote the manuscript; Chun Yang and Hong-yu Zhou searched the literature and extracted data; Hong-yu Zhou analyzed the data; Bo Qin, Zhe Yuan and Limin Chen supervised the study and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript, including the authorship list.