Background and rationale. Age is one of the predictors for sustained virological response (SVR) when treating chronic hepatitis C (CHC) patients with pegylated-interferon/ribavirin (PegIFN/RBV). However, the treatment responses of the young patients had not been analyzed before. Therefore, we conducted this study to investigate the treatment responses of CHC patients younger than 40 years old (y/o).

Material and methods. We retrospectively analyzed our prospective cohort of genotype 1 (GT1)- and genotype 2 (GT2)-CHC patients who received 24-week PegIFN/RBV treatment. We divided these patients into two groups according to their age younger or older than 40 y/o. Clinical parameters including viral responses and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of interleukin–28B (IL28B) had been analyzed.

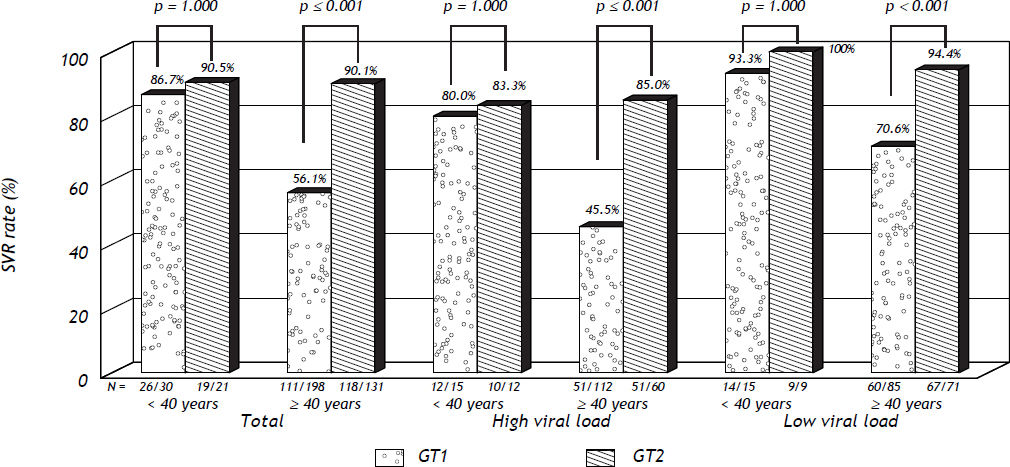

Results. In GT1-CHC patients, the rapid, complete early viral response rates and the SVR rate were significantly higher in patients younger than 40 y/o. In GT–1 CHC patients younger than 40 y/o, the SVR rate was similar to the GT2-CHC patients, either with high or low baseline viral load. As for the SVR predictors, in CHC patients younger than 40 y/o, only BMI but not the genotype of HCV, not baseline viral load, and not IL28B SNP was the predictor.

Conclusions. GT1-CHC patients younger than 40 y/o had SVR rate similar to GT2-CHC patients. The IL28B polymorphism had no impact on the SVR rate in these young GT1-CHC patients.

Current treatment strategy for patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC) is a combination therapy of pegylated interferon-α/ribavirin (PegIFN/RBV) and individualization of treatment duration based on genotype of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and on-treatment viral response.1,2 With the recommended therapy, the sustained virological response (SVR) rate could be achieved around 42–79% for genotype–1 (GT1) chronic hepatitis C (CHC) patients and 76–95% for genotype–2/3 (GT2/3) CHC patients.2 In addition, rapid virological response (RVR) is regarded as an important on-treatment predictor for SVR.3–5 Furthermore, the achievement of RVR could lead to a shorten treatment duration from 48 weeks to 24 weeks for GT1 CHC patients with low baseline viral load without compromising the treatment efficacy.5–9

For predicting the SVR, genotypes of HCV, stages of liver fibrosis, baseline viral load and age were the known predictors.10–12 Recently, the genotypes of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of Interluekin–28B (IL28B) were also found to be the critical SVR predictor in patients with GT-1 CHC but not GT2/3 CHC.13–16 Among these predictors, age is an intriguing one. It had already been reported that older age is a risk factor for liver cirrhosis in patients with CHC.17 Furthermore, older patients with age more than 65 years old were associated with higher withdrawal rate and associated with inferior treatment responses.18,19 On the contrary, there were some studies showing the patients younger than 40 years old (y/o) would benefit more from combination therapy than older patients in PegIFN/RBV treatment.20 However, a detailed analysis of the treatment responses in CHC patients younger than 40 y/o had not been reported before.

We therefore investigated this issue in order to extend our understanding about the characteristic of these younger patients, especially their responses to treatment and the relationship to other predictors in a prospective cohort of CHC patients treated with a 24-week therapy of PegIFN/RBV from a large medical center.

Material and MethodsPatientsWe retrospectively analyzed a prospective cohort of consecutive adult (more than 18 years old) Taiwanese treatment-naïve patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 and genotype 2 who visited HCV team of Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Linkou Medical Center, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, and received 24 weeks of combination therapy with PegIFN/RBV between February 2002 and July 2010, and who agreed to provide blood samples for the human genome study. The dose of PegIFN was either 180 μg per week for pegylated interferon-α 2a or 1.5 μg/kg per week for pegylated interferon-α 2b. A fixed dose of Ribavirin with either 1,000 mg or 1,200 mg per day was prescribed. Dose modifications of pegylated interferon and ribavirin for adverse events and laboratory abnormalities were performed in a stepwise manner as described in product information. Patients with decompensated liver disease, hepatoma, cancer of any origin, co-infection with hepatitis B virus or with human immunodeficiency virus, with apparent autoimmune hepatitis, metabolic liver disease, genetic liver disease and alcoholic liver disease were excluded from this cohort. No pregnant or breastfeeding patients had received treatment. All patients included in this study had received liver biopsies that were evaluated by one pathologist using Metavir scoring system.21 The Metavir fibrosis stage of the portal tract was as follows:

- •

0: no fibrosis.

- •

1: enlarged portal tract without septa.

- •

2: enlarged portal tract with rare septa.

- •

3: numerous septa without cirrhosis.

- •

4: cirrhosis.

Mild liver fibrosis was defined as F1 and F2 and advanced fibrosis as F3 and F4. HCV genotype was determined by a genotype specific probe based assay in the 5’ untranslated region (LiPA; Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium). There were 380 patients in total. Patients who fit to 80/80/80 adherence rule (more than 80% of total PEG-IFN and total RBV doses and more than 80% of the total duration of therapy) were defined as treatment-adherence.

Definitions of response to treatment were undetectable serum HCV-RNA levels 24 weeks after cessation of treatment as SVR, undetectable serum HCV-RNA levels at 4 week after starting treatment as RVR, and undetectable serum HCV-RNA levels at week 12 after starting treatment as complete early virological response (cEVR).

The HCV-RNA levels in this study were measured using a commercial quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay VERSANT HCV RNA 3.0. Assay (HCV 3.0 bDNA assay, Bayer Diagnostics, Berkeley, Calif., lower limit of detection: 5.2 x 102 IU/mL) or COBAS TaqMan HCV Test (TaqMan HCV; Roche Molecular Systems Inc., Branchburg, N.J., lower limit of detection: 15 IU/mL). If non-detection of HCV-RNA by VERSANT HCV RNA 3.0. Assay, it would be tested further by COBAS® AMPLICOR HCV Test, v2.0 (CA V2.0, Roche Diagnostic Systems., lower limit of detection: 50 IU/mL).

Genomic DNA extraction and IL28 B genotypingAnti-coagulated peripheral blood was obtained from HCV patients. Genomic DNA was isolated from EDTA anti-coagulated peripheral blood using the Puregene DNA isolation kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN) as previously described.22 The oligonucleotide sequences flanking ten IL28B polymorphisms were designed as primers for Taqman allelic discrimination. The allele specific primers for rs12979860 were labeled with a fluorescent dye (FAM and VIC) and used in the PCR reaction. Aliquots of the PCR product were genotyped with allele specific probe of SNPs using real time PCR (ABI).

Ethics statementsAll patients in this study had provided written informed consent. This study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethical Committees of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

Statistical analysisChi-square tests with Fisher’s exact test where appropriate were used to compare the categorical variables of the groups. Continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations (SDs) and compared using Mann-Whitney U test or Student’s t-test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses for predictors of sustained virological response were conducted using patients’ demographic, clinical variables and IL28B SNPs. The clinical variables included gender, age, viral load of HCV-RNA, liver fibrosis, body mass index (BMI), glycohemoglobin (HbA1c), and alanine transaminase.

The odds ratios (OR) were also calculated. All P values less than 0.05 by the two-tailed test were considered statistically significant. Variables that achieved a statistical significance less than 0.10 on univariate analysis were entered into multivariate logistic regression analysis to identify the significant independent predictive factors. All statistical analyses were performed with statistical software SPSS for Windows (version 16, SPSS. Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

ResultsYounger patients with GT1 HCV infection had different treatment responseDemographic characteristics of these 380 CHC patients enrolled in this prospective cohort were shown in table 1. There were 228 genotype 1 (GT1) and 152 genotype 2 (GT2) CHC patients. These patients were divided into two groups according to their ages younger than 40 y/o (younger age group) or older than 40 y/o (older age group). As shown in table 1, there were no differences between these two age groups in terms of gender, baseline viral titer and body mass index (BMI) in both GT1 and GT2-CHC patients. However, percentages of advanced fibrosis, liver cirrhosis and HbA1C increased in older age group in both GT1 and GT2-CHC patients. The alanine transaminase (ALT) levels and adherence percentage decreased in older age group in patients of GT1 but not in GT2-CHC patients.

Demographic characteristics of chronic hepatitis C patients treated with PegIFN/RBV.

| Variable | HCV genotype | Total (n = 380) | < 40 years (n = 51) | ≥ 40 years (n = 329) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y/o (mean ± SD) | GT1 | 52.1 ± 10.9 | 32.9 ± 5.5 | 55.0 ± 8.2 | < 0.001 |

| GT2 | 51.6 ± 10.1 | 33.7 ± 3.8 | 54.4 ± 7.6 | < 0.001 | |

| P value | 0.639 | 0.841 | 0.645 | ||

| Gender: male, n (%) | GT1 | 135 (59.2) | 21 (70.0) | 114 (57.6) | 0.197 |

| GT2 | 84 (55.3) | 12 (57.1) | 72 (55.0) | 0.852 | |

| P value | 0.446 | 0.344 | 0.640 | ||

| RNA ≥ 0.4 × 106 IU/mL, n (%) | GT1 | 127 (55.9) | 15 (50.0) | 112 (56.9) | 0.481 |

| GT2 | 72 (47.4) | 12 (57.1) | 60 (45.8) | 0.334 | |

| P value | 0.101 | 0.615 | 0.050 | ||

| Advanced fibrosis, n (%) | GT1 | 113 (50.0) | 6 (20.0) | 107 (54.6) | < 0.001 |

| GT2 | 75 (49.3) | 3 (14.3) | 72 (55.0) | 0.001 | |

| P value | 0.900 | 0.720a | 0.947 | ||

| LC, n (%) | GT1 | 83 (36.7) | 2 (6.7) | 81 (41.3) | < 0.001 |

| GT2 | 49 (32.2) | 2 (9.5) | 47 (35.9) | 0.016 | |

| P value | 0.369 | 1.000a | 0.323 | ||

| BMI, ≥ 25 kg/m2, n (%) | GT1 | 88 (38.6) | 11 (36.7) | 77 (38.9) | 0.816 |

| GT2 | 59 (38.8) | 6 (28.6) | 53 (40.5) | 0.299 | |

| P value | 0.966 | 0.546 | 0.776 | ||

| HbA1c, % (mean ± SD) | GT1 | 5.7 ± 1.1 | 5.4 ± 1.0 | 5.7 ± 1.1 | 0.004 |

| GT2 | 5.8 ± 1.0 | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 5.9 ± 1.1 | 0.002 | |

| P value | 0.226 | 0.985 | 0.210 | ||

| ALT, IU/L (mean ± SD) | GT1 | 145.5 ± 105.3 | 209.1 ± 155.7 | 135.9 ± 92.3 | 0.018 |

| GT2 | 155.0 ± 112.9 | 161.9 ± 136.3 | 153.8 ± 109.3 | 0.789 | |

| P value | 0.367 | 0.320 | 0.190 | ||

| rs12979860 (CC allele) n (%) | GT1 | 28 (12.3) | 5 (16.7) | 23 (11.6) | 0.385a |

| GT2 | 16 (10.5) | 4 (19.0) | 12 (9.2) | 0.240a | |

| P value | 0.601 | 1.000a | 0.479 | ||

| Adherence, n (%) | GT1 | 200 (87.7) | 30 (100) | 170 (85.9) | 0.031a |

| GT2 | 149 (98.0) | 21 (100.0) | 128 (97.7) | 1.000a | |

| P value | < 0.001 | - | < 0.001 |

The numbers of patients in GT1 and GT2 were 200 and 149 in the total, 30 and 21 in the group < 40 years, 170 and 128 in the groups ≥ 40 years.

As for the comparison between GT1 and GT2-CHC patients, all the factors like gender, baseline viral load, advanced fibrosis, liver cirrhosis, BMI and levels of ALT were similar between GT1 and GT2 CHC patients and in each group. We also analyzed the genotype of IL28B SNP, as shown in table 1, the advantageous allele (CC) of rs12979860 had similar distributions between these two age groups and between GT1 and GT2-CHC patients.

We then compared the responses to the treatment in these two age groups with different genotype of HCV. For both RVR and cEVR, there was no difference between these two age groups in either GT1 or GT2-CHC patients (Table 2). As for the SVR rates, they were significantly lower in older age group than younger age group in patients with GT1 CHC (age < 40 y/o vs. age ≥ 40 y/o: 86.7% vs. 56.1%, p = 0.001) but not in GT2 CHC patients (age <40 y/o vs. age ≥ 40 y/o: 90.5% vs. 90.1%, p = 1.000).

The impact of age on the RVR, EVR and SVR in patients with CHC, GT1 and GT2.

| Variable | Genotype | Total (N = 380) | < 40 years (N = 51) | ≥ 40 years (N = 329) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RVR, n (%) | GT1 | 145 (63.6) | 22 (73.3) | 123 (62.1) | 0.234 |

| GT2 | 112 (73.7) | 15 (71.4) | 97 (74.0) | 0.8 | |

| P value | 0.039 | 0.881 | 0.024 | ||

| cEVR, n (%) | GT1 | 166 (72.8) | 22 (73.3) | 144 (72.7) | 0.945 |

| GT2 | 124 (81.6) | 15 (71.4) | 109 (83.2) | 0.226a | |

| P value | 0.049 | 0.881 | 0.027 | ||

| SVR, n (%) | GT1 | 137 (60.1) | 26 (86.7) | 111 (56.1) | 0.001 |

| GT2 | 137 (90.1) | 19 (90.5) | 118 (90.1) | 1.000a | |

| P value | < 0.001 | 1.000a | < 0.001 |

RVR: rapid virologie response. cEVR: complete early virologie response. SVR: sustained virological response.

Because all the GT1 and GT2-CHC patients in our cohort were treated with PegIFN/RBV for 24 weeks, it would then be an advantage to compare the treatment responses in different age groups between GT1 and GT2 CHC patients based on same treatment duration. As shown in table 2, the RVR and cEVR and SVR rates were significantly lower in patients with GT1 CHC than patients with GT2 CHC (SVR: GT1 CHC vs. GT2 CHC: 60.1% vs. 90.1%, p < 0.001). Interestingly, the difference of SVR rates between GT1 and GT2 patients was statistically significant only in older age group (GT1 CHC vs. GT2 CHC: 56.1% vs. 90.1%, p < 0.001) but not in younger age group (GT1 CHC vs. GT2 CHC: 86.7% vs. 90.5%, p = 1.000). Furthermore, the SVR rate of younger GT-1 CHC patients was similar to the SVR rate of total GT-2 CHC patients (younger GT1 CHC vs. total GT2 CHC: 86.7% vs. 90.1%, p = 0.534). Therefore, these data indicated in GT-1 CHC patients younger than 40 years old, their treatment responses were similar to GT2-CHC patients.

For further exploring the possibility that the treatment behaviors were similar between younger GT1 and total GT2 CHC patients under 24-week treatment, we sub-grouped these patients according to the baseline viral load. As shown in figure 1, the SVR rate was similar between GT1 and GT2-CHC patients for either all the patients or these patients with either high or low baseline viral load. In contrast, in patients older than 40y/o, the SVR rate was significantly lower in GT1 patients than in GT2-CHC patients in all the patients and in those patients with high and low viral load (Figure 1).

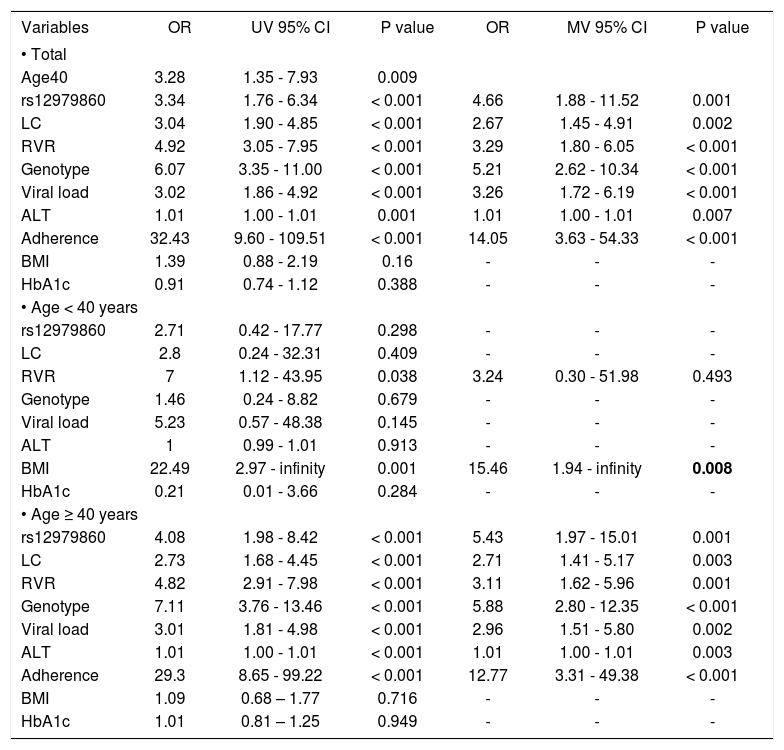

Different predictors for SVR in younger and older age patients with chronic HCV infectionBecause the above results indicated similar SVR rates between GT1 and GT2 CHC in younger patients who received 24-week treatment, we next studied the predictors for SVR in this prospective cohort with both GT1 and GT2 CHC patients included. First of all, the factor of age of 40 was a predictor for SVR by univariate logistic analysis (Table 3). In addition, we found the genotype of rs12979860, liver cirrhosis, RVR, genotype of HCV, baseline viral load, ALT levels and adherence were the predictors for SVR in all these patients and in older age group as well (Table 3). However, for younger age group, only BMI was the predictors for SVR. The genotype of the rs12979860, liver cirrhosis, genotype of HCV, baseline viral load and ALT levels could not predict the SVR in the patients younger than 40 y/o (Table 3).

Predictors of SVR by univariate and multivariate Logistic regression analysis.

| Variables | OR | UV 95% CI | P value | OR | MV 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| • Total | ||||||

| Age40 | 3.28 | 1.35 - 7.93 | 0.009 | |||

| rs12979860 | 3.34 | 1.76 - 6.34 | < 0.001 | 4.66 | 1.88 - 11.52 | 0.001 |

| LC | 3.04 | 1.90 - 4.85 | < 0.001 | 2.67 | 1.45 - 4.91 | 0.002 |

| RVR | 4.92 | 3.05 - 7.95 | < 0.001 | 3.29 | 1.80 - 6.05 | < 0.001 |

| Genotype | 6.07 | 3.35 - 11.00 | < 0.001 | 5.21 | 2.62 - 10.34 | < 0.001 |

| Viral load | 3.02 | 1.86 - 4.92 | < 0.001 | 3.26 | 1.72 - 6.19 | < 0.001 |

| ALT | 1.01 | 1.00 - 1.01 | 0.001 | 1.01 | 1.00 - 1.01 | 0.007 |

| Adherence | 32.43 | 9.60 - 109.51 | < 0.001 | 14.05 | 3.63 - 54.33 | < 0.001 |

| BMI | 1.39 | 0.88 - 2.19 | 0.16 | - | - | - |

| HbA1c | 0.91 | 0.74 - 1.12 | 0.388 | - | - | - |

| • Age < 40 years | ||||||

| rs12979860 | 2.71 | 0.42 - 17.77 | 0.298 | - | - | - |

| LC | 2.8 | 0.24 - 32.31 | 0.409 | - | - | - |

| RVR | 7 | 1.12 - 43.95 | 0.038 | 3.24 | 0.30 - 51.98 | 0.493 |

| Genotype | 1.46 | 0.24 - 8.82 | 0.679 | - | - | - |

| Viral load | 5.23 | 0.57 - 48.38 | 0.145 | - | - | - |

| ALT | 1 | 0.99 - 1.01 | 0.913 | - | - | - |

| BMI | 22.49 | 2.97 - infinity | 0.001 | 15.46 | 1.94 - infinity | 0.008 |

| HbA1c | 0.21 | 0.01 - 3.66 | 0.284 | - | - | - |

| • Age ≥ 40 years | ||||||

| rs12979860 | 4.08 | 1.98 - 8.42 | < 0.001 | 5.43 | 1.97 - 15.01 | 0.001 |

| LC | 2.73 | 1.68 - 4.45 | < 0.001 | 2.71 | 1.41 - 5.17 | 0.003 |

| RVR | 4.82 | 2.91 - 7.98 | < 0.001 | 3.11 | 1.62 - 5.96 | 0.001 |

| Genotype | 7.11 | 3.76 - 13.46 | < 0.001 | 5.88 | 2.80 - 12.35 | < 0.001 |

| Viral load | 3.01 | 1.81 - 4.98 | < 0.001 | 2.96 | 1.51 - 5.80 | 0.002 |

| ALT | 1.01 | 1.00 - 1.01 | < 0.001 | 1.01 | 1.00 - 1.01 | 0.003 |

| Adherence | 29.3 | 8.65 - 99.22 | < 0.001 | 12.77 | 3.31 - 49.38 | < 0.001 |

| BMI | 1.09 | 0.68 – 1.77 | 0.716 | - | - | - |

| HbA1c | 1.01 | 0.81 – 1.25 | 0.949 | - | - | - |

UV: univariate logistic regression analysis. MV: multivariate logistic regression analysis. OR: odds ratio. CI: confidence interval. rs12979860: CC allele vs. non-CC alleles. LC: liver cirrhosis vs. non-liver cirrhosis. RVR: RVR vs. non-RVR. BMI: < 25kg/m2vs. ≥ 25kg/m2. Genotype: GT 2 vs. GT1. Viral load: baseline HCV-RNA < 0.4 × 106 IU/mL vs. ≥ 0.4 × 106 IU/mL); ALT: IU/L; HbA1c: percentage.

Taken together, our data indicated GT-1 CHC patients with age younger than 40 years old belonged to a unique group of patients. For these young patients, the percentage of advanced fibrosis and liver cirrhosis was significantly lower and adherence percentage significantly higher than older patients, though the gender, BMI and baseline viral load were similar in both groups. In addition, the SNP of IL28B had no impact on the SVR in these younger patients though this SNP was a powerful predictor for SVR in older patients. Furthermore, by 24-week PegIFN/RBV treatment, these younger patients with GT1CHC, either with high or low baseline viral load, could achieve similar SVR rates to the patients with GT2-CHC.

DiscussionA combination therapy of PegIFN/RBV is a well-accepted standard treatment for patients with chronic hepatitis C.1,2 Age, along with genotype of HCV, liver fibrosis, baseline viral load, RVR and genotype of IL28B SNP, were important predictors for SVR.10–12,23,24 In all these factors, only genotype of HCV, RVR and baseline viral load, but not age or genotype of IL28B SNP, had been considered as deciding parameters for developing the treatment strategy.1,2 In addition, the current recommended treatment duration by PegIFN/RBV is 48 weeks for GT1 patients and is 24 weeks for GT2 CHC. However, for GT1 CHC patients with RVR and low baseline viral load, an abbreviated 24-week treatment rather than 48-week treatment could be considered.9 Herein, we provided evidence showing GT1-CHC patients younger than 40 years old had similar SVR rate to GT2-CHC patients under 24-week combination therapy. Furthermore, these similar SVR rates between younger GT1 and all GT2-CHC patients still hold true for patients with either high or low baseline viral load. In addition, the predictor for SVR in younger patients is BMI only. The genotype of the rs12979860, advanced fibrosis, RVR, genotype of HCV, baseline viral load and ALT levels cannot predict the SVR in younger patients though these factors are good predictors for GT-1CHC patients older than 40 years old. All these results indicate that the population of GT-1CHC patients younger than 40 years old is a unique group with treatment behavior similar to GT-2 CHC patients but different from GT-1 CHC patients older than 40 years old.

Patients younger than 40 years old usually have different diseases characteristic, either clinical or genetic features, from patients older than 40 years old, like early onset type II diabetes,25,26 young-adult hypertension27,28 and young-adult hepatocellular carcinoma.29,30 Therefore, people younger than 40 years of age represented a group of patients different from patients older than 40 year of age. On the other hand, as for the patients with CHC, previous clinical trials had shown age younger than 40 years old was a predictor for SVR.20,31 Based on these observations, we chose the age of 40 to define the young age group and found the GT1-CHC patients younger than 40 years old had better SVR rate than patents older than 40 years old. On the other hand, when investigated the on-treatment responses in different age groups of both GT1 and GT2 CHC patients, we found young age group did achieve significantly higher RVR, cEVR and SVR rates. These results implied that the age factor per se could affect the viral kinetic responses after PegIFN/RBV treatment.

On the other hand, recent genome-wide associated studies have demonstrated strong evidence that SNPs of IL28B were significantly correlated with SVR when GT1 CHC patients were treated with PegIFN/RBV.13–16 In Taiwanese patients, we had found the same phenomenon.32 In addition, it was proposed that a high prevalence of advantageous allele of IL28B SNP in Taiwan could be the possible explanation for the high SVR rate in Taiwanese patient.32 In the present studies, the genotype of rs12979860 was found again as a powerful predictor for SVR in our patients. However, in GT1 CHC patients younger than 40 years old, the genotype of rs12979860 lost their predictive ability. This implied that the younger patients might possess stronger immune responses after PegIFN/RBV treatment that could overcome the detrimental effect on the immune responses by the disadvantageous allele of IL28B SNPs.

In Taiwanese patients, due to the policy of national health insurance reimbursement, both GT1 and GT2-CHC patients had received 24-week treatment of PegFN/RBV.2 Therefore, the GT1 and GT2 CHC patients we enrolled in this prospective cohort were all treated with 24 weeks of PegIFN/RBV. Though it was not a standard treatment policy suggested internationally, it was just an advantage to explore the influence of age on the treatment outcome in patients with different genotypes of HCV infection but with same treatment duration. As demonstrated in our data, though the SVR rates were significantly lower in GT1-CHC patients than GT2-CHC patients, the SVR rates were similar between both GT1 of the younger age patients and GT2 patients. In addition, this similarity in SVR rates between younger GT1 and GT2 CHC patients is still existed for patients with either high or low baseline viral load. These evidences indicate that the treatment-response behavior between young GT1 and GT2 CHC patients is comparable.

On the other hand, it was intriguing that only BMI was the SVR predictor in younger CHC patients. The genotype of HCV was not a predictor for SVR in these younger CHC patients. This observation again strongly suggested that patients younger than 40 years old belonged to a unique group that genotypes of HCV would not be an important factor to decide the treatment duration. Therefore, data from the present study implied that for GT–1 CHC patients younger than 40 years old, 24-week treatment would be satisfactory for both high and low baseline viral load. However, further randomized clinical trial would be necessary to prove this possibility.

In conclusion, our data demonstrated that genotype of the SNP of IL28B had no impact on the SVR rate in GT1 CHC patients who were younger than 40 years old. In addition, these GT1 CHC patients younger than 40 years old had the SVR rate similar to GT2 CHC patients but significantly higher than GT1 CHC patients older than 40 years old. Based on our results, we concluded GT1 CHC patients who are younger than 40 years old behave similarly to GT2 CHC patients but differently from GT1 CHC patients older than 40 years old.

Acknowledgments and DisclosuresWe greatly appreciated the secretarial and clerkical helps from Hui-Chuan Cheng, Mon-Tzy Lu, PeiLing Lin. Conflict of interest: All the authors do not have any commercial or other association that might pose a conflict of interest

Financial SupportThis work was supported by NMRP: 98–3112-B-182A–003 and NMRP: 360021 from the National Science Council, Taiwan, and CMRPG 390682, 37542, 360463 from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.