Hepatitis-associated aplastic anemia (HAAA) is a distinct variant of acquired aplastic anemia, in which an acute attack of hepatitis leads to marrow failure and pancytopenia.1 Similar to other cases of acquired aplastic anemia (AA), HAAA results from an autoimmune attack directed against hematopoeitic stem/ progenitor cells. AA and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) are closely related bone marrow failure disorders.2 We report the first case of severe HAAA-PNH associated with non-A-E Hepatitis virus infection that was treated with high dose cyclophosphamide therapy and then subsequent allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT).

A 22 Year old old female presented to the emergency room with 1 month history of generalized purpura and epistaxis.

Two months prior to admission, she had a selflimiting flu-like syndrome associated with transaminitis. Laboratory tests revealed aspartate transaminase (AST) 450 IU/L (normal 5-40 IU/L), alanine transaminase (ALT) 120 IU/L (7-56 IU/L), alkaline phosphatase 300 IU/L, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 450 IU/L, total bilirubin 3.2 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 2.4 mg/dL, serum albumin 3.8 g/dL (normal 3.5-5.5 g/dL) and an international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.8 (normal 0.9-1.2). A very extensive viral hepatitis workup was done including polymerase chain reaction assays for Hepatitis A, B, C, D, E and G, Epstein Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, parvovirus B19, human herpes virus 6 and 8 which were all negative. The serum protein electrophoresis was normal and the markers for autoimmune hepatitis (antinuclear antibodies, anti-smooth muscle antibodies, anti-mitochondrial antibodies and anti-liver kidney microsome antibodies) were all negative. Her serum ceruloplasmin level was 30mg/dL and the 24 hour urinary copper level was 28 mcg/24 h and these laboratory results excluded the diagnosis of Wilson’s disease. She was eventually diagnosed with non-A-E hepatitis infection. The transient infection was self-limiting and after 2 weeks, she clinically improved and repeat laboratory blood tests revealed normalization of transaminases and liver function tests [(AST) 42 IU/L, (ALT) 53 IU/L, alkaline phos-phatase 90 IU/L, LDH 150 IU/L, total bilirubin 1.0 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 0.4 mg/dL, serum albumin 3.5 g/dL and an INR of 1.0].

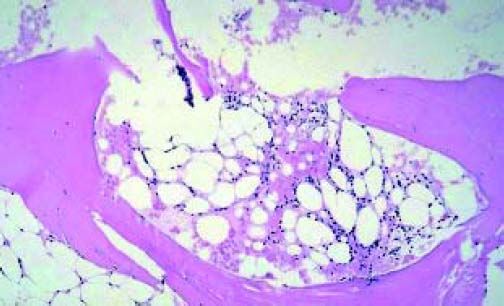

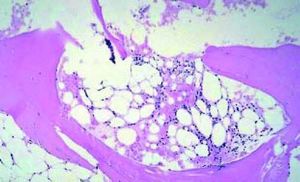

At admission this time, she complained of generalized fatigue, weakness and palpitations. She did not have a history of smoking, alcohol or illicit drug use. She was a college student. She denied any family history of liver or hematological diseases. Her physical exam revealed pallor and generalized purpura on her upper and lower extremities. Lab tests revealed pancytopenia (Hb 5.3 g/dL, reticulocytes 5.6 x 109/L, leukocytes 3,200/L with differentiation 15% neutrophils, 70% lymphocytes and 8% monocytes, platelets 13,000/L). No iron, folic acid and vitamin B12 depletion were encountered. She did not use medications and had not been exposed to toxic materials. Computed Tomography scan of the abdomen was negative for any lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. Direct coombs test was negative. Initially, high-dose oral prednisolone at 1 mg/ kg/day was administered but her platelet count did not improve. Her AST was 240 IU/L, (ALT) 368 IU/ L and alkaline phosphatase 210 IU/L. Her total and direct bilirubin concentrations were observed to be 4.5 mg/dL and 0.6 mg/dL respectively. His lactate dehydrogenase concentration was high, at 545 IU/L, and her serum haptoglobin had decreased to 10 mg/ dL. Her urine was tested for hemosiderin and it was positive. These findings were suggestive of intravascular hemolysis. A bone marrow biopsy was done (Figure 1) and it revealed hypocellularity (< 5 %) without any other (including cytogenetic) abnormalities. Flow cytometry of the peripheral blood that detected glycosylphosphatidylinositol (PI)-deficient clones in 45, 30, and 1 % of the granulocyte, monocyte, and erythroid lineages, respectively. The diagnosis of severe aplastic anemia-paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria was made. The patient was referred to a bone marrow transplant center where she received high dose cyclophosphamide therapy and subsequently an allogeneic BMT. Three months post-transplant, she presented to the clinic for follow-up and she had no clinical complaints and lab results were unremarkable.

Several features of the HAAA syndrome suggest that the marrow aplasia is caused by immunological dysregulation which triggers the activation of cytotoxic lymphocytes to produce increased amounts of gamma interferon and cytokines.3 We hypothesize that the PNH clone may also be a manifestation of this cytokine cascade. PNH is an acquired clonal hematopoietic stem cell disorder that occurs following the expansion and differentiation of a hematopoietic stem cell harboring a PIG-A mutation. This mutation manifests as affected blood cells which are deficient in glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GP1)-anchored proteins, two of which (CD55 and CD59) are important complement regulatory proteins.4 The clinical and prognostic significance of PNH clone in HAAA has not been described. In our case, it contributed to hemolytic anemia. Studies are underway to evaluate the immunopathophysiology of HAAA and if serial evaluation of the PNH clone can provide specific reference points to monitor response to immune therapy.5

Conflict of InterestWe do not have any conflict of interest.