The burden of liver disease is a significant concern, yet it is often underestimated. Liver disease results in approximately 2 million deaths annually and contributes to 1 in 25 deaths worldwide [1]. Compared to other chronic conditions, such as diabetes and chronic heart diseases, patients with end-stage liver disease frequently experience longer and more frequent hospital admissions[2–4].

Liver fibrosis and cirrhosis are the outcomes of virtually all liver diseases, and they are the primary causes of death related to liver disease[5,6]. This condition is marked by the buildup of fibrillary extracellular matrix (ECM) within and surrounding the liver tissue, causing damage that leads to scarring, cirrhosis, and eventually liver failure[7]. In 2019, liver cirrhosis contributed to 1.5 million deaths in patients with liver disease[8], with Central Asia having the highest liver cirrhosis-related age-standardized death rate (ASIR) of 59.06 and Central Latin America having the second-highest ASIR of approximately 40.76 per 100,000 population[8].

Recent advances have increased our understanding of liver fibrosis, and the pathogenic mechanisms involved[9–12]. Furthermore, the use of antiviral medications for viral hepatitis B and C has revealed the potential for reversing liver fibrosis by eliminating its causative agents, halting the progression of fibrosis, or managing its complications. Despite these advancements, liver fibrosis remains a significant healthcare and economic burden, and treatment options for liver fibrosis remain limited, with liver transplantation being the primary option. Thus, there is an urgent need to explore novel approaches for the development of antifibrotic drugs.

“Energy Homeostasis” is a fundamental aspect of cellular health that is altered in pathological conditions, including liver fibrosis[13]. The transformation of quiescent stellate cells into fibrous matrix-secreting cells is an energy-dependent process, leading to an increased energy demand in these cells during liver fibrosis. Disruptions in energy metabolism have been linked to the development of liver fibrosis and could provide a potential target for innovative antifibrotic drug development[13]. In this review, we discuss the role of energy metabolism in liver fibrosis and the potential for exploiting this mechanism as a novel therapeutic approach.

2Pathogenesis of liver fibrosisLiver fibrosis is a complex process characterized by various cellular and extracellular signaling events regulated at the transcriptional, translational, and post-transcriptional levels. Both genetic and epigenetic factors significantly influence these interactions[14,15].

Upon liver injury, hepatocytes trigger an inflammatory response and produce apoptotic bodies. These bodies can be engulfed by hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), which initiate their activation. This sustained damage disrupts the liver's normal microenvironment, resulting in a cytokine storm and the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) plays a significant role, both of which further lead to HSC activation. Once activated, HSCs release various vasoactive peptides, growth factors, and cytokines that exacerbate fibrosis. Consequently, there is an accumulation of ECM proteins, such as collagen types I and III, which leads to the formation of fibrous scar tissue in the liver. This ultimately impairs normal liver function and promotes the progression of liver fibrosis[14,16].

Several signaling pathways are implicated in this process, including those involving connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), inflammatory cytokines (such as leptin, Interferon-ɣ (IFN-ɣ), and reduced adiponectin levels), as well as transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), vascular endothelial factor (VEGF), and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)[17,18]. Notably, TGF-β is considered the archetypal profibrotic cytokine, and its expression is elevated in all fibrotic diseases. It exerts its effects through either the (Drosophila MAD or Mothers Against Decapentaplegic) SMAD-dependent signaling pathway or the non-SMAD signaling pathway, ultimately leading to increased collagen production. Excessive collagen and ECM accumulation will develop fibrosis and scar formation, which in turn would lead to impaired liver functions, portal hypertension, cirrhosis and liver failure[19,20].

3Energy metabolismEnergy metabolism is the process of generating energy from nutrients and is essential for maintaining balance within an organism's cells, ensuring proper functionality and homeostasis[21]. The main source of energy metabolism comes from macronutrients (carbohydrates, fats and proteins) as well as other specific molecules that help in energy production. Energy is primarily produced through oxidative phosphorylation (mitochondrial metabolism) and the oxidation of fatty acids. Another source of energy is autophagy[22–25].

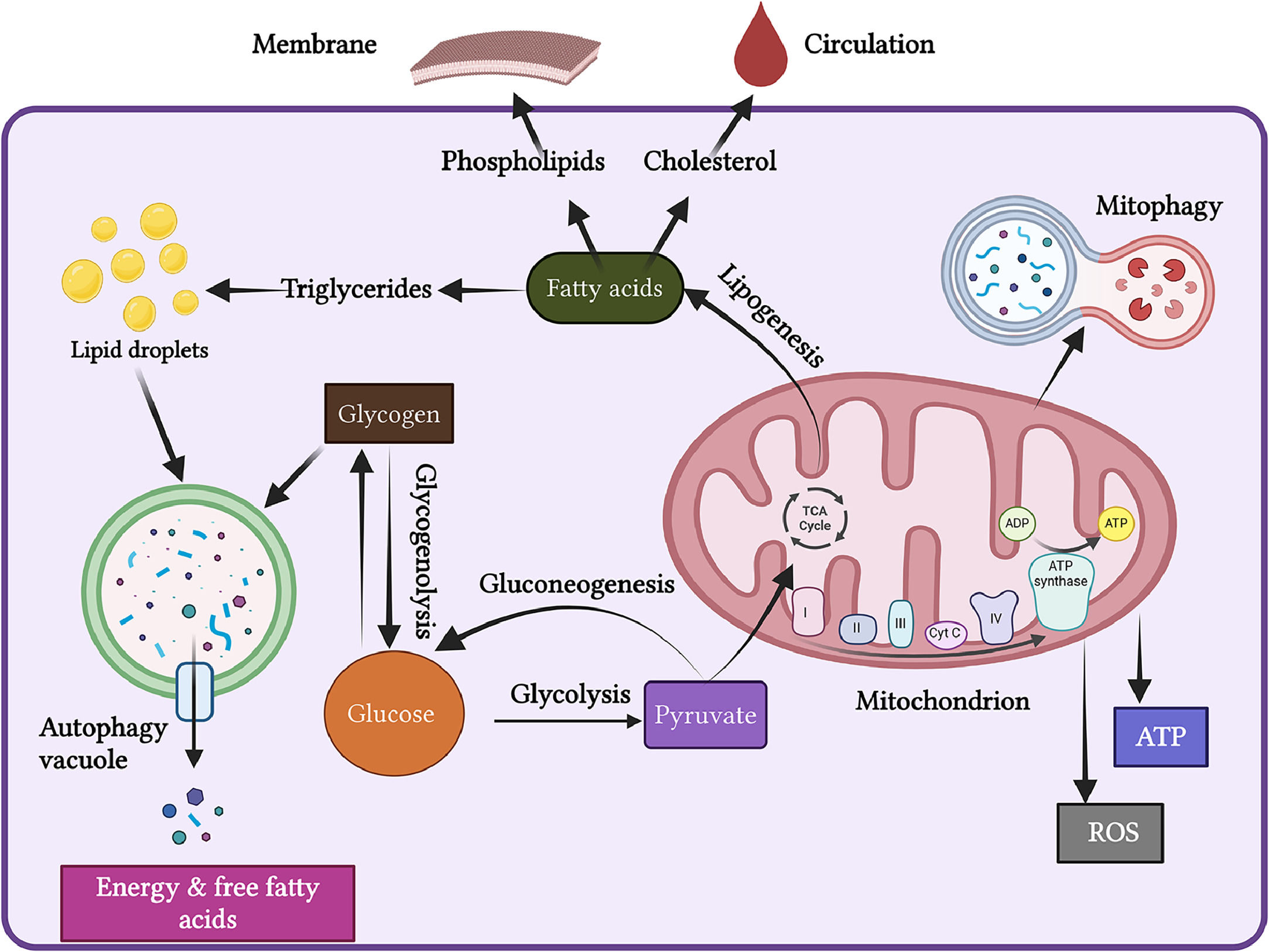

The liver is a vital metabolic organ that regulates the body's energy metabolism. It metabolizes glucose into pyruvate through glycolysis. The mitochondria then fully oxidize pyruvate to generate ATP via oxidative phosphorylation and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (Figure 1).

Energy Metabolism. The liver is a vital organ that regulates energy metabolism. It converts glucose into pyruvate through glycolysis. The mitochondria then fully oxidize pyruvate to generate ATP via oxidative phosphorylation and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. During periods of starvation, autophagy ensures a continuous energy supply when external nutrients are limited.

During the fed state, products of glycolysis undergo lipogenesis, leading to the synthesis of fatty acids. These fatty acids can be stored as triglycerides in lipid droplets, incorporated into membrane structures as phospholipids, or released into circulation as cholesterol esters. Additionally, the liver produces glucose through glycogenolysis (the breakdown of glycogen) and gluconeogenesis (the synthesis of glucose) [26].

During fasting, the liver generates endogenous glucose and fatty acids through gluconeogenesis and lipolysis using stored energy reserves. Fatty acids undergo mitochondrial β-oxidation and ketogenesis to produce ketone bodies, which serve as a metabolic fuel for non-hepatic tissues. Several factors, including the cAMP-response binding protein (CREB), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1 alpha (PGC-1α), and forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1), along with sympathetic and parasympathetic stimulation, regulate the enzymes that control various steps of liver metabolism, thereby influencing liver energy metabolism. Disruption of liver energy metabolism can lead to various diseases, including diabetes and metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) [26].

3.1Mitochondrial function and energy productionMitochondria are often referred to as “the powerhouse of the cell,” as they are essential for cellular energy metabolism. They generate energy from glucose and fatty acids through two key metabolic pathways: the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and electron transport chain (ETC). These pathways release energy stored in food in the form of high-energy electrons (Figure 1) [27,28].

As semi-autonomous organelles, mitochondria are involved in ATP synthesis and the generation of ROS. The inner membrane of the mitochondria contains enzymes that participate in both the ETC and ATP production while also maintaining an electrochemical gradient. These enzymes are essential for the oxidative phosphorylation[29,30].

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) are crucial in capturing these electrons, forming NADH and FADH2. Both NADH and FADH2 transfer electrons into the ETC, which is the primary site for ATP generation and consists of five complexes (I to V). As electrons move through these complexes, they help establish a proton gradient. The energy released from this proton transfer is then used to convert ADP into ATP[31]. However, approximately 2% of electrons are released from the electron transport chain while traversing these complexes, combining with oxygen to produce ROS[32]. Dysregulation of mitochondrial energy and redox signaling can disrupt mitochondrial homeostasis and is implicated in various diseases [33].

Mitochondrial homeostasis is maintained through several processes, including mitochondrial fission, fusion, mitophagy, and biogenesis. Mitochondrial fission separates damaged mitochondria from healthy ones and is regulated by dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) and mitochondrial fission protein 1 (FiS1). In contrast, mitochondrial fusion combines neighbouring, depolarized mitochondria to form healthy organelles, a process stimulated by the cells’ energy demands[34]. Defects in mitochondria can trigger both fission and fusion processes, further disrupting mitochondrial homeostasis [35]. Mitochondrial biogenesis helps regulate mitochondrial turnover by expressing PGC-1α, which functions as a transcriptional coactivator [36].

3.2Autophagy and energy productionAutophagy is a catabolic process within cells that directs damaged or surplus organs to the lysosomes for breakdown into amino acids, free fatty acids or other small molecules, which are then recycled or used for energy production. Typically triggered by factors like energy depletion, stress, or inflammation, autophagy is considered a survival mechanism essential for maintaining cellular balance. Starvation activates autophagy, whereas insulin, free fatty acids, obesity, and ageing inhibit it [37]. It is implicated in various human diseases, including fibrotic conditions[38].

During periods of starvation, autophagy plays a crucial role in cellular adaptation by facilitating energy management. During these times, autophagy of glycogen (glycophagy) ensures a continuous energy supply when external nutrients are limited. Additionally, autophagy is involved in the breakdown of lipid droplets, which are intracellular fat stores. This process releases fatty acids, which can be used as an alternative energy source when glucose is scarce. Together, the actions of autophagy contribute to maintaining cellular energy balance and supporting survival during nutrient deprivation [39,40]. Impaired autophagy leads to hepatic metabolic dysfunction, causing lipid droplet accumulation and increased ROS generation. It also promotes fibrosis directly by providing energy to activate HSCs[41].

3.3Autophagy and mitochondria: a reciprocal relationship in metabolic reprogramming and energy productionMitochondria and autophagy exhibit a complex and interdependent relationship that plays a critical role in cellular homeostasis, metabolic reprogramming, and energy production. Autophagy is responsible for degrading defective mitochondria, while mitochondria influence various aspects of autophagy, including the production of autophagosomes and the overall autophagic process[42,43].

One of the key mechanisms involved in this relationship is mitophagy, the explicit process of removing damaged mitochondria. This process is initiated by specific proteins, particularly PINK1 (PTEN-induced kinase 1) and PARK2 (Parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase). PINK1 accumulates on the outer mitochondrial membrane of damaged mitochondria, sensing mitochondrial dysfunction. Once activated, PINK1 recruits Parkin, which ubiquitinates various proteins on the mitochondrial surface. This ubiquitination serves as a signal for the recruitment of p62 (also known as SQSTM1), which links the tagged mitochondria to LC3 (microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3), a key protein involved in autophagosome formation.

Additionally, multiple mitophagy receptors, including BNIP3L (Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa interacting protein 3-like), FUNDC1 (FUN14 domain-containing protein 1), PHB2 (prohibitin 2), cardiolipin, and BNIP3 assist in the process by binding to Atg8 family proteins, such as LC3 and GABARAP, to help encapsulate the damaged mitochondria within autophagosomes. This coordinated action ensures that damaged mitochondria are effectively identified and targeted for degradation, thereby maintaining mitochondrial quality control and cellular health [44]. Dysregulation of the PINK1/Parkin pathway or alterations in the expression of its components can significantly impair the mitophagy process and lead to the accumulation of damaged mitochondria[45]. In short, the intricate interplay between autophagy and mitochondria is vital for maintaining cellular quality control and energy homeostasis.

4Energy metabolism reprogramming in liver fibrosisHepatic cells maintain strict metabolic regulation to ensure proper cellular function. However, under diseased conditions, these cells undergo metabolic reprogramming to meet their energy demands, facilitating trans-differentiation and the performance of new roles [46].

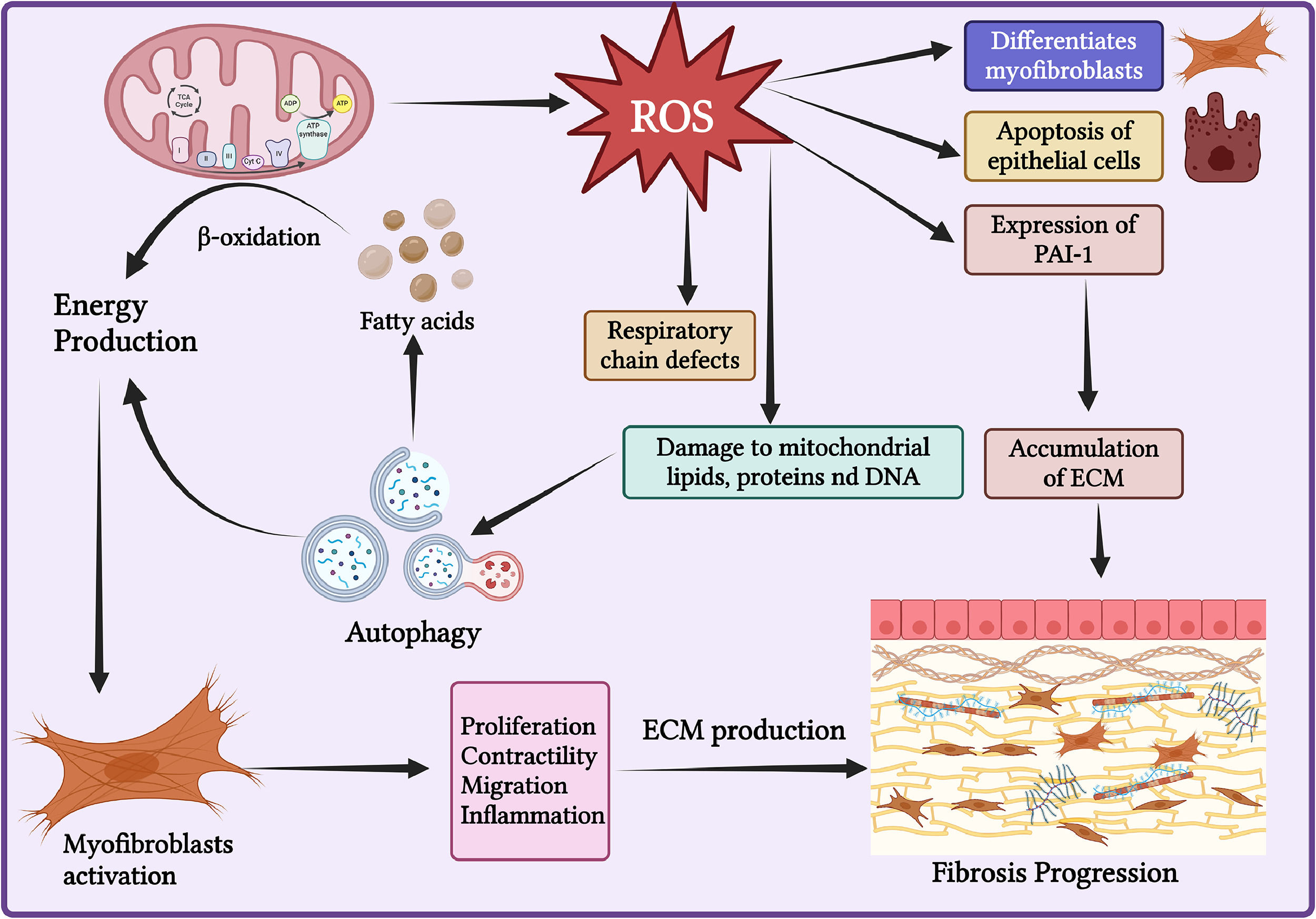

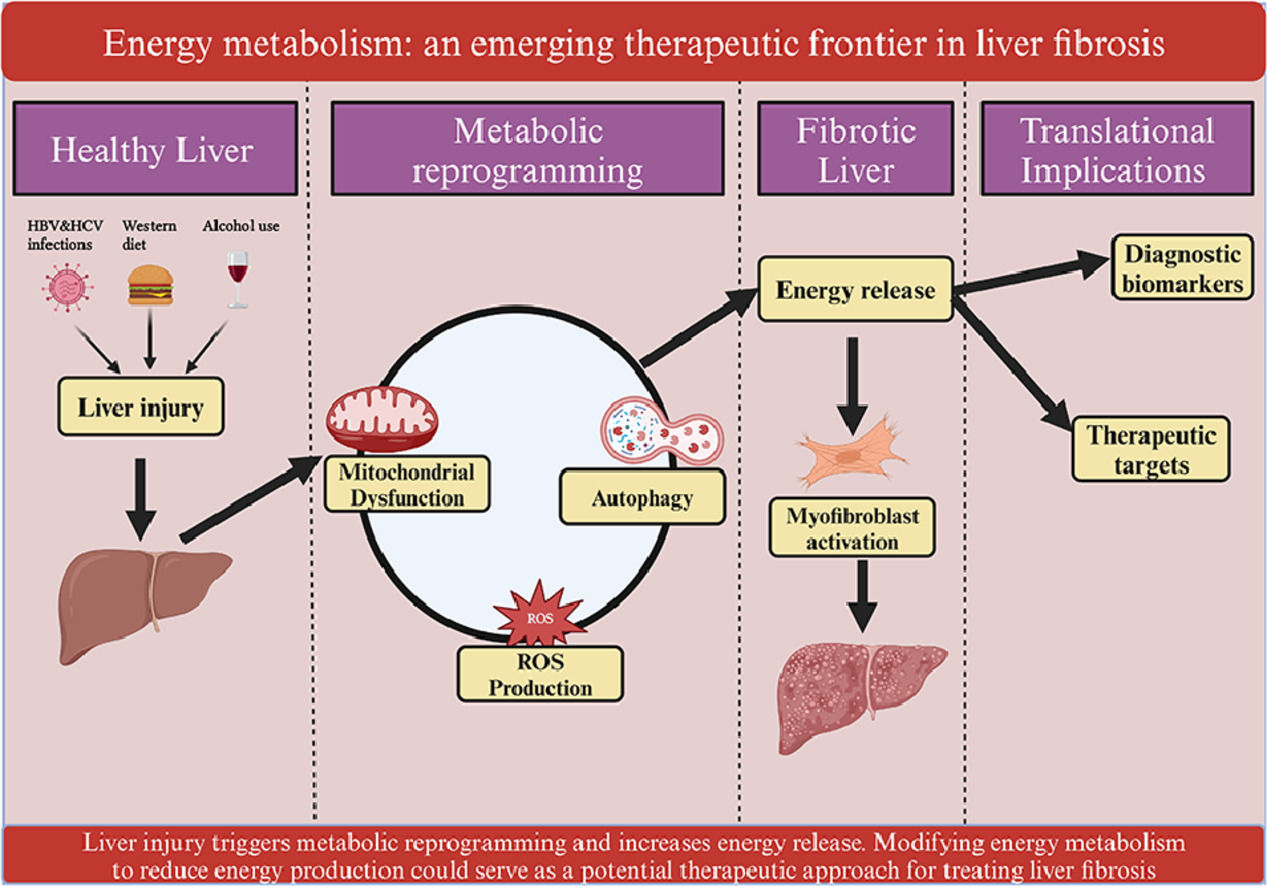

In a quiescent state, HSCs function as pericytes storing retinoids (vitamin A and its metabolites) in cytoplasmic lipid droplets[47] and regulating sinusoidal blood flow. Following liver injury, various inflammatory and metabolic changes lead to the activation of HSCs accompanied by loss of retinol stores and lipid droplets in activated rodents, primary and immortalized human HSCs[48,49]. Various evidence suggests the reduction in retinoids is involved in the development of various diseases. However, the precise mechanism is not fully understood yet[49]. These retinoids are replaced by polyunsaturated triglycerides during HSCs activation. Upon activation, activated HSCs utilize these lipid droplets to facilitate their transformation into myofibroblasts[50], [51]. These myofibroblasts exhibit increased proliferation, contractility, migration, inflammation, and enhanced ECM production. Collectively, these changes contribute to the development of fibrosis and cirrhosis (Figure 2) [52].

Energy Metabolism Reprogramming in Liver Fibrosis. During liver fibrosis, hepatic cells undergo metabolic reprogramming to meet their energy demands. There is an increase in various mitochondrial and autophagic activities that enhance energy release to support the activation of myofibroblasts. Additionally, during liver injury, the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) also increases, which is crucial for the activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and the development of fibrosis.

The transition from quiescent HSCs to the myofibroblast stage involves substantial metabolic reprogramming. This includes enhanced glycolysis, mobilization of lipid droplets, increased β-oxidation, and elevated glutaminolysis. Additionally, cell-intrinsic stress pathways, such as unfolding protein response (UPR) and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress are activated[53].

Alterations in HSC carbohydrate metabolism and increased lipogenesis have been noted in rat models of liver fibrosis [54], [55]. Additionally, various changes in mitochondrial and autophagic activities are involved in HSC activation and liver fibrosis. The increased energy demand of cells during liver fibrosis promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and enhances energy production [35]. Altered mitochondrial activity and activated HSCs have been observed in cirrhotic patients [56,57], with increased mitochondrial oxidation noted in individuals with MAFLD[58].

ROS plays a crucial role in the differentiation of myofibroblasts, the apoptosis of epithelial cells, and the expression of profibrogenic mediators, such as PAI-1. This process suppresses the degradation of the ECM, leading to ECM accumulation and liver fibrosis[59]. An imbalance in ROS production and removal results in increased oxidative damage to mitochondrial lipids, proteins, and DNA, which in turn can induce autophagy and enhance energy release [60]. ROS also causes defects in the respiratory chain and mitochondrial biogenesis[61]. The accumulation of ROS is crucial for HSC activation and the development of liver fibrosis.

Autophagy is also critical for HSC activation. During liver injury, it mobilizes lipid droplets, releasing free fatty acids that mitochondria then use for energy production through β-oxidation to fulfill the energy requirements of activated HSCs during proliferation and fibrosis[62,63]. In vivo studies in mice have demonstrated that specific deletion of autophagy-related 7 (Atg7) in HSCs reduces liver fibrosis. Profibrotic cytokines, such as TGF-β1, can induce autophagy in HSCs, which increases the expression of the autophagy-related protein LC3II/I, potentially further activating HSCs and reducing apoptosis [38,64,65]. Additionally, the activation of the ER stress pathway is closely linked to autophagy induction[53]. Thus, regulating mitochondrial homeostasis and modulating autophagy to reduce energy production could be explored as treatment options for liver fibrosis.

5Genetics and energy metabolismThe phenotypic manifestations and severity of liver fibrosis, much like other complex traits, arise from intricate interactions between genetic factors and environmental influences[66,67]. Recent progress in our understanding of the genetic underpinnings of liver fibrosis has led to the identification of various gene variants that play significant roles in its development. Some of the key genetic variants associated with liver fibrosis include Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3), transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 (TM6SF2), membrane-bound O-acyltransferase domain-containing 7 (MBOAT7), and hydroxysteroid 17β-dehydrogenase (HSD17B13)[15].

A critical aspect of these genetic variations is their modulation of energy metabolism, which has emerged as a fundamental mechanism linking certain gene variants to the progression of liver fibrosis. For instance, the PNPLA3 I148M variant is known to exacerbate liver disease through its effects on de novo lipogenesis (DNL)[68]. This variant not only reduces DNL but also enhances mitochondrial β-oxidation and ketogenesis, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction that can contribute to the progression of various liver diseases[69]. Another study has shown that the PNPLA3 I148M variant leads to the accumulation of intracellular free cholesterol. This accumulation disrupts normal mitochondrial function and induces a fibrotic phenotype in HSCs. Additionally, PNPLA3 has been implicated in the process of lipophagy[68].

Another example is the rs8736 variant in the MBOAT7 gene, which is associated with reduced expression levels of the MBOAT7 protein. Expression of MBOAT7 protein is downregulated in patients with steatohepatitis. This deficiency can lead to alterations in mitochondrial function and morphology. Notably, the shape of mitochondria is intricately linked to their bioenergetic efficiency; changes in mitochondrial morphology can significantly impact cellular energy metabolism, thereby influencing the overall cellular energy metabolism[10,70].

In addition to these genes, other genetic factors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis and energy metabolism. For example, mutations in the autophagy-related gene 7 (ATG7) have been associated with liver damage, particularly by impairing the autophagy process in individuals with metabolic disorders[70]. Other notable genes include peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα), which is involved in the oxidation of fatty acids, and its dysregulation can lead to lipid accumulation in the liver[71]; on the other hand, the mitochondrial genome coding for the NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase chain 1 (MT-ND1) gene has been shown to impair oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondrial function and increased production of ROS that can induce oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage[72]; finally, Parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase (PRKN) is crucial for mitochondrial quality control and the autophagy process as it tags damaged mitochondria for degradation through mitophagy[73]. Collectively, these genetic variations contribute to a complex network of mechanisms that dictate the progression and severity of liver fibrosis through energy metabolism.

6Epigenetics and energy metabolismEpigenetics refers to heritable changes in gene expression or cellular phenotype that occur without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Recent findings have demonstrated the significant impact of epigenetic mechanisms on various aspects of fibrogenesis in the liver[9,11,74]. There is a strong link between epigenetics and energy metabolism in mediating liver fibrosis. Several mechanisms, including DNA methylation, histone modification, and the activity of non-coding RNAs, play crucial roles in the development of liver fibrosis and are also involved in energy metabolism[75,76].

Activated HSCs undergo a process known as “cellular reprogramming,” adjusting their metabolism to ensure a continuous supply of energy necessary for growth and proliferation. This ongoing nutrient synthesis affects the pool of metabolites available for chromatin-modifying enzymes that regulate fibrogenic gene expression [77,78]. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) is responsible for the removal of histone functional groups, and the post-translational modification of histone tails regulates transcriptional activity by modulating chromatin compaction. HDAC influences liver energy metabolism and alleviates liver fibrosis in vivo[79]. Conversely, epigenetic changes can also influence the expression of genes related to energy metabolism. For instance, the epigenetic modification of PGC-1α has been shown to reduce mitochondrial fission, activating HSCs and contributing to liver fibrosis. The Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) enzyme, which regulates mitochondrial function and autophagy, may undergo epigenetic silencing due to histone acetylation, leading to liver fibrosis[75,80].

DNA methylation, another key epigenetic mechanism, is implicated in the regulation of both energy metabolism and liver fibrosis. Using targeted bisulfite sequencing analysis, significant hypermethylation has been identified in the CpG99 regions of the PNPLA3 I148M variant in patients with advanced liver fibrosis (stages F3-F4) associated with MAFLD[11,81]. Similarly, Methyl CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2) is a methyl-binding protein that causes transcriptional silencing at sites of DNA methylation. MECP2 mediates the epigenetic silencing of PPARɣ, which regulates adipogenesis, fatty acid storage, and glucose metabolism, thereby reducing the activity of HSCs [82]. Conversely, reversing DNA hypermethylation-based epigenetic silencing of PPARɣ gene expression through the administration of the DNA methylation inhibitor analogue 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-azadC) restores its expression and suppresses the activation of HSCs [82].

In summary, epigenetic changes and energy metabolism play interconnected roles in the development and progression of liver fibrosis. As such, understanding these epigenetic modifications and their effects on biological functions could offer opportunities for developing novel therapeutic strategies to treat liver fibrosis.

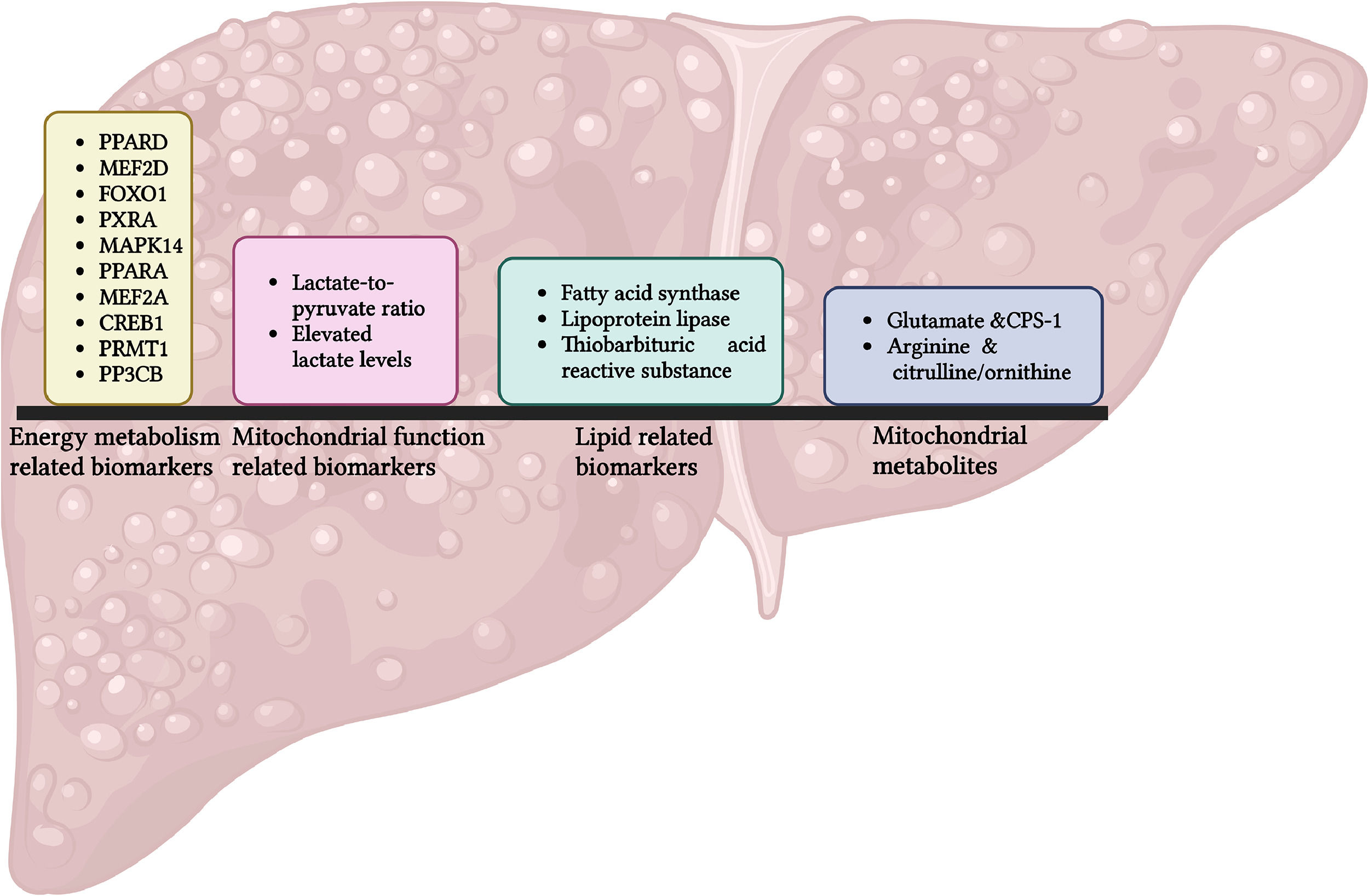

7Translational implications7.1Energy metabolism as biomarkersBiomarkers related to energy metabolism are increasingly recognized as valuable diagnostic tools for various diseases (Figure 3).

For example, a study has identified approximately ten biomarkers associated with energy metabolism, including PPARD, MEF2D, FOXO1, PXRA, MAPK14, PPARA, MEF2A, CREB1, PRMT1, and PPP3CB using random forest and support vector algorithms. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis demonstrated strong predictive accuracy for a nomogram, with an Area Under the ROC Curve (AUROC) of 0.91 and 0.84 to predict the risk of heart failure in two distinct cohorts[83].

Changes in the lactate-to-pyruvate (L:P) ratio can reflect alterations in mitochondrial function that affect energy metabolism, a common pathway in liver fibrosis. Elevated lactate levels suggest impaired oxidative phosphorylation, frequently observed in fibrotic liver. Measurements of blood lactate and the lactate-to-pyruvate ratio have been proposed as biomarkers for diagnosing mitochondrial diseases in paediatric patients with acute liver failure. However, these measurements should be complemented with other diagnostic techniques [84].

Metabolites related to fatty acid metabolism can also serve as biomarkers for liver injury and liver fibrosis. Disruptions in lipid metabolism during liver fibrosis result in a distinctive pattern of fatty acid derivatives that can be detected in blood or tissue samples. Lipogenic enzymes, such as fatty acid synthase (FAS) and lipoprotein lipase (LPL), along with the lipid metabolite thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS), could be proposed as new lipid biomarkers for MAFLD [85].

Furthermore, several mitochondrial metabolites can act as biomarkers for liver fibrosis. For example, glutamate and carbamoyl phosphate synthase 1 (CPS-1), along with arginine, citrulline, and ornithine have shown potential. Increased levels of glutamate and CPS-1 may serve as biomarkers for diagnosing liver fibrosis, with an AUROC of 0.95 for the detection of advanced fibrosis. Conversely, decreased levels of arginine and the citrulline/ornithine ratio may also be utilized as biomarkers for liver fibrosis, presenting an AUROC of 0.94 for the same comparison [86].

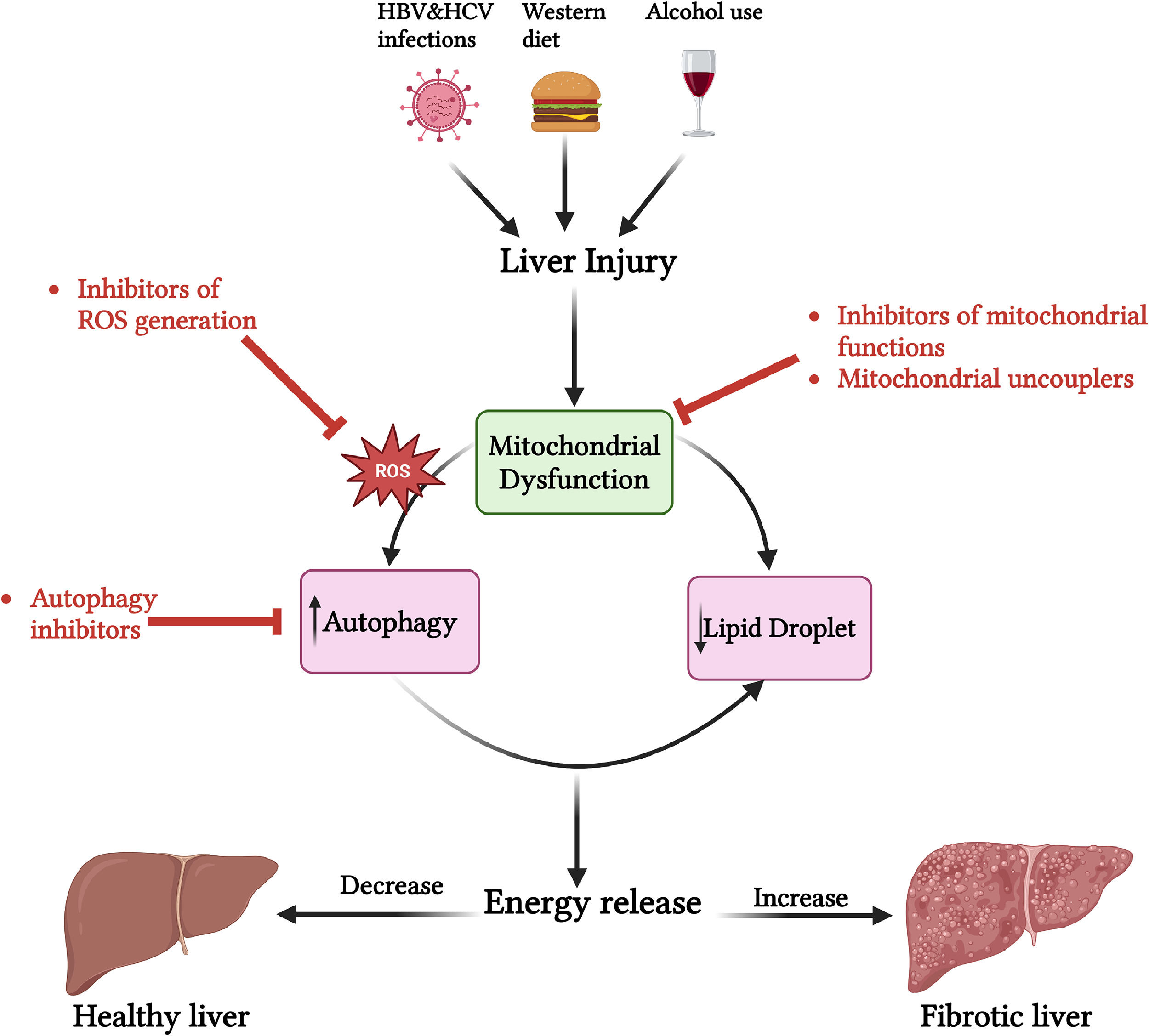

7.2Regulation of energy metabolism as a therapeutic targetModifying energy metabolism to decrease energy production may serve as a potential therapeutic approach for treating liver fibrosis (Figure 4).

Regulation of energy metabolism as a therapeutic approach for liver fibrosis. Liver injury leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, increased ROS generation, and autophagy, resulting in energy release. This process contributes to the activation of HSCs and the progression of liver fibrosis. Regulating energy metabolism to reduce energy release has the potential to reverse liver fibrosis. Various inhibitors, including those targeting ROS, mitochondrial function, and autophagy, can reduce energy release and thereby help reverse liver fibrosis.

Evidence suggests that inhibitors of mitochondrial function can reduce cellular energy demand and potentially reverse liver fibrosis [87]. For instance, the use of 3-bromopyruvate (3-BrPA), which decreases the level of mitochondrial ATP5E to inhibit energy production, has been shown to limit liver fibrosis in both mice and human HSCs [88]. Additionally, increased mitochondrial fission has been implicated in the activation of HSCs, while inhibiting this fission can reduce liver fibrosis in mice treated with carbon tetrachloride (CCL4)[53]. Mitochondrial electron transfer, facilitated by proton flux, is coupled with a redox proton pump and involves mitochondrial complexes I, III, and IV. Mitochondrial uncouplers can redirect the energy generated by electron transfer in the respiratory chain, causing it to be released as heat rather than being used for the phosphorylation of ADP. Recently, mitochondrial uncouplers have been shown to reduce ATP and ROS generation, thereby inhibiting the activation of HSCs [89].

Inhibition of ROS generation can also help attenuate fibrosis. The administration of GKT137831 (a NOX1/NOX4 inhibitor) decreased generation of ROS and reduced expression of profibrogenic genes were observed in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced primary fibrotic mice and human HSCs[90,91]. Additionally, bilirubin acts as a direct ROS scavenger; the use of bilirubin/cyclopamine-loaded nanoparticles (RHB/Cyc NPs) has demonstrated ROS scavenging capabilities and HSC deactivation, leading to ameliorated liver fibrosis in CCl4-induced fibrotic mice[92].

Inhibiting autophagy can also reduce HSC activation, preserve lipid droplets, and alleviate fibrosis [93]. Bafilomycin A1, a macrolide antibiotic that inhibits autophagy at the late stage, decreased HSC activation and proliferation by attenuating autophagy [94]. Another autophagy inhibitor, chloroquine, has been shown to improve CCl4-induced liver fibrosis by reducing HSC activation through the suppression of autophagy [95].

Additionally, various natural and synthetic compounds have been demonstrated to reduce liver fibrosis in different fibrotic models by regulating autophagy. For instance, Quercetin (a plant flavanol) downregulates autophagy in HSCs by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway, which slows down the progression of fibrosis [96]. Fucoidan (a polysaccharide found in brown algae) ameliorates fibrosis by reducing autophagy in CCl4 and bile duct ligation-induced fibrotic mouse models [97]. Moreover, several synthetic compounds have also been reported to reduce fibrosis, including aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-D-ribofuranoside (AICAR), probucol, carvedilol, hydroxychloroquine, cyclosporin A, and doxazosin. AICAR, an adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase (AMPK) agonist, inhibits lysosomal autophagic flux, which measures autophagic degradation activity. Probucol is a bisphenol-type compound that inhibits autophagy and increases FXR expression. Carvedilol, a third-generation non-selective β-blocker, inhibits autophagy and increases apoptosis in HSCs while affecting lysosomal pH and p62 levels. Hydroxychloroquine, a 4-aminoquinoline derivative antimalarial drug, also inhibits autophagy. Cyclosporin A, an immunosuppressant, can decrease PINK/Parkin-mediated mitochondrial autophagy. Other compounds include a protein kinase inhibitor (PKC) that inhibits the autophagy marker LC3-II and impairs autophagy and an FXR agonist that inhibits the expression of LC3-II, also impairing autophagy. Doxazosin blocks autophagic flux through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway [97].

Finally, modulating the metabolic alterations in activated HSCs that contribute to energy release could be a potential strategy for treating fibrosis. For instance, oroxylin, a flavonoid with various biological functions, has been shown to inhibit glycolysis and fibrogenic activities, thereby reducing fibrosis in murine disease models [98]. Additionally, activated HSCs exhibit increased lipogenesis, suggesting that inhibiting DNL may alleviate liver fibrosis and is currently being investigated as a therapeutic approach for MAFLD [55]. The energy sensor AMPK, an evolutionarily conserved serine/threonine protein kinase found in eukaryotic cells, acts not only as a sensor of cellular energy stress but also as a core hub for maintaining cellular energy homeostasis. Recent studies have indicated that AMPK activation improves liver damage and fibrosis[99]. Furthermore, FGF21 plays a crucial role in regulating energy metabolism, acting both centrally and peripherally to influence energy expenditure[100]. Recent studies have shown that FGF21 is paradoxically increased in patients with metabolic diseases, influencing translation kinetics[101].

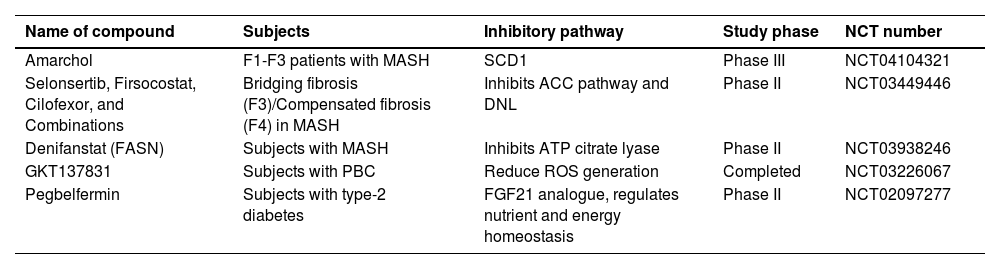

A reduction in energy release to mitigate liver fibrosis through pharmacological inhibition of various pathways is summarized in Table 1 for phase II/III clinical trials. Ongoing advancements in understanding specific molecular and metabolic processes can pave the way for the development of individualized treatments aimed at curing liver fibrosis.

Compounds that reduce liver fibrosis by inhibiting energy release

| Name of compound | Subjects | Inhibitory pathway | Study phase | NCT number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amarchol | F1-F3 patients with MASH | SCD1 | Phase III | NCT04104321 |

| Selonsertib, Firsocostat, Cilofexor, and Combinations | Bridging fibrosis (F3)/Compensated fibrosis (F4) in MASH | Inhibits ACC pathway and DNL | Phase II | NCT03449446 |

| Denifanstat (FASN) | Subjects with MASH | Inhibits ATP citrate lyase | Phase II | NCT03938246 |

| GKT137831 | Subjects with PBC | Reduce ROS generation | Completed | NCT03226067 |

| Pegbelfermin | Subjects with type-2 diabetes | FGF21 analogue, regulates nutrient and energy homeostasis | Phase II | NCT02097277 |

Clinical trials for the pharmacological agents that reduce liver fibrosis by inhibiting energy release107-112. Stearoyl-CoA-desaturase (SCD1), acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase (ACC), de novo lipogenesis (DNL) Reactive oxygen species (ROS), fibroblasts growth factor 21(FGF21), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), Metabolic dysfunction associated steatohepatitis (MASH) National Clinical Trial (NCT).

Modulating energy metabolism presents a promising approach for treating liver fibrosis, but it also comes with challenges and numerous unresolved questions related to both the underlying biology and clinical translation that future studies need to address. These challenges can be categorized into general issues related to antifibrotic drugs and specific concerns regarding this approach.

Although many antifibrotic agents have demonstrated promising results in animal studies, their effectiveness in human clinical trials has largely been suboptimal[102]. This limitation may be attributed to several factors, including species differences (the animal models may not accurately recapitulate the human disease phenotype), the complexity of chronic diseases (the duration of disease in animals is often shorter than in humans), drug pharmacokinetics (as evidenced by varied responses to pharmacological inhibition, genetic inactivation, antisense oligonucleotides, and small interfering RNAs), and limitations in clinical trial designs (such as insufficient magnitude and consistency of antifibrotic effects)[103,104].

Specifically, challenges related to modulating energy metabolism include identifying which pathways can be targeted to reduce cellular energy release and how these pathways can be adjusted to regulate ATP synthesis and consumption. This need is particularly pressing given that HSCs exhibit remarkable plasticity[105], thus requiring a comprehensive understanding of the metabolic reprogramming involved in this condition at the single-cell level.

Furthermore, it is essential to improve our understanding of how mitochondrial dysfunction—including potential alterations in mitochondrial health and overall metabolic balance—contributes to the progression of liver fibrosis and whether it can be precisely targeted to reverse fibrosis. We must determine how energy production can be selectively reduced in fibrotic cells without compromising the liver's overall metabolic function. Designing therapies that selectively target activated HSCs or other fibrogenic cells without affecting normal cells is another critical issue[106].

Another aspect that warrants investigation is identifying the optimal stage of fibrosis (early or advanced) that would benefit most from reduced energy production, or whether this approach can be effectively applied at all stages. We need to understand the potential off-target effects of reducing energy production and how to mitigate them. Additionally, considering the long-term consequences of decreasing energy production and managing the associated risks is crucial. These issues could potentially be addressed through the development of gene- and cell-type-specific delivery systems such as oligopeptide complexes, nanoparticles, liposomes, and CRISPR. Finally, exploring the feasibility of personalized treatment approaches based on a patient's genetic and metabolic profile may yield effective strategies to reduce energy production in liver cells.

9ConclusionsLiver fibrosis poses a significant and unmet clinical challenge that necessitates the development of novel therapeutic strategies. HSCs, which play a crucial role in the progression of liver fibrosis, undergo metabolic reprogramming that aligns with the demands of their excessive activation. This metabolic shift not only supports their fibrogenic activity but also contributes to the advancement of hepatic fibrosis.

Instead of solely focusing on cell signaling pathways, targeting the energy demand of fibrosis represents a novel strategy to combat liver fibrosis while minimizing the impact on quiescent stellate cells. By targeting specific metabolic pathways that drive the overactivation of fibrogenic cells—particularly HSCs—it may be possible to reverse the fibrotic process. This innovative treatment paradigm could transform drug development for liver fibrosis by introducing new intervention methods.

However, implementing such metabolic modifications does not come without challenges. There are potential concerns regarding the impact on normal liver function, the ability of the liver to regenerate effectively, and potential systemic effects that could arise from altering cellular metabolism. These considerations require careful evaluation and thorough research.

Future studies should aim to identify and understand various metabolic pathways that can effectively hinder the energy release necessary for the progression of fibrosis. In addition to metabolic interventions, there is potential to incorporate epigenetic and gene-based therapeutic strategies that target specific pathways related to energy production in the context of liver fibrosis. This approach could lead to individualized and targeted therapies for the prevention, reversal, and management of liver fibrosis.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributionsThe conception, and drafting the manuscript were performed by II and ME. All authors critically reviewed, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Uncited ReferencesME is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) investigator and ideas grants (AAP2008983 and APP2001692). MLY is supported by the "Center of Excellence for Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease, National Sun Yat-sen University, Kaohsiung" from The Featured Areas Research Centre Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan.