Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a major psychiatric complication of liver transplantation (LT). Here, we aimed to analyze the impact of de novo MDD on survival post-LT and identify risk factors for this disorder among LT recipients.

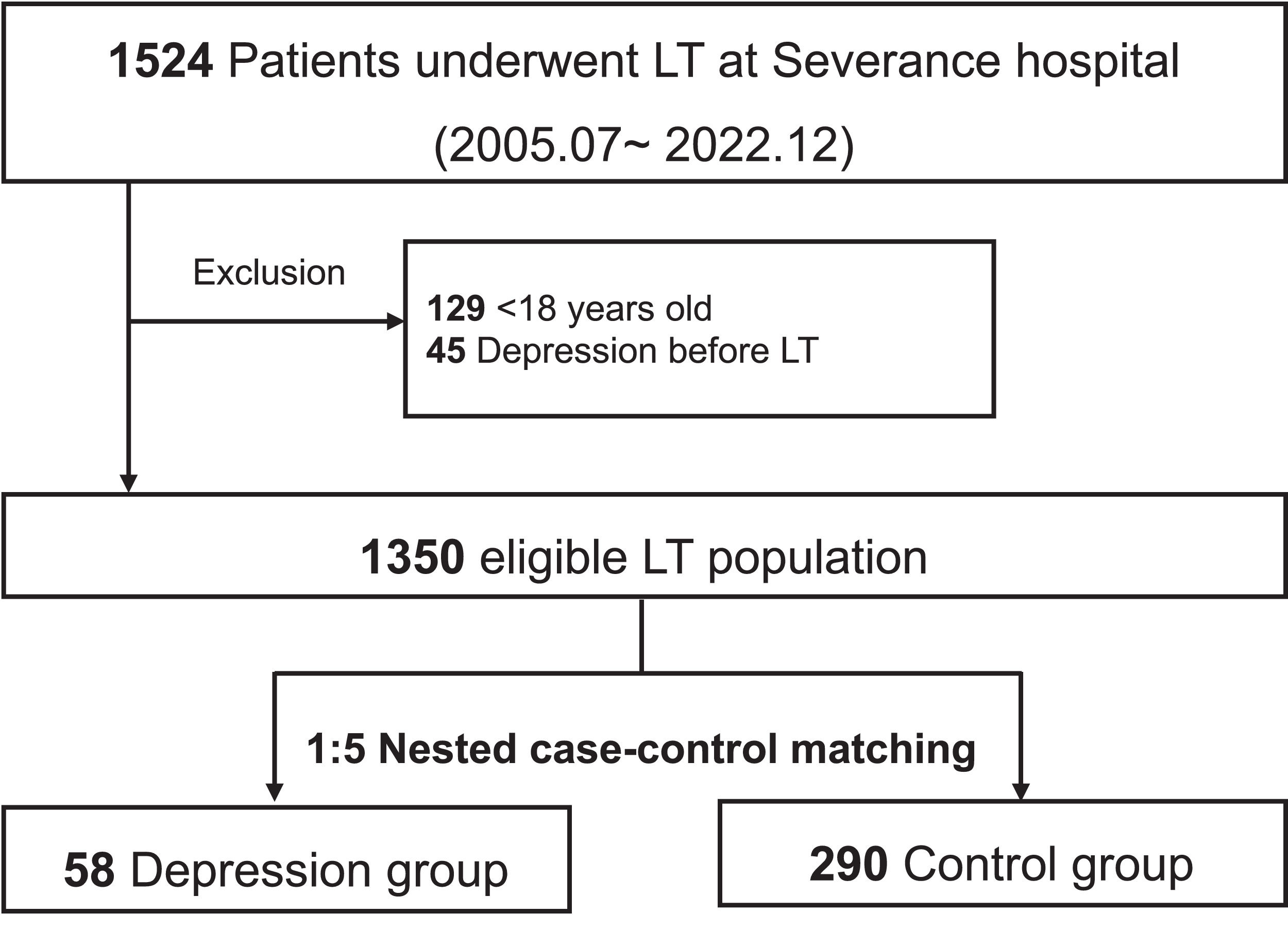

Materials and methodsA retrospective analysis was conducted on 1350 LT recipients at Severance Hospital, Korea, from July 2005 to December 2022. Patients with MDD were matched 1:5 with controls using a nested case-control design to control for immortal time bias.

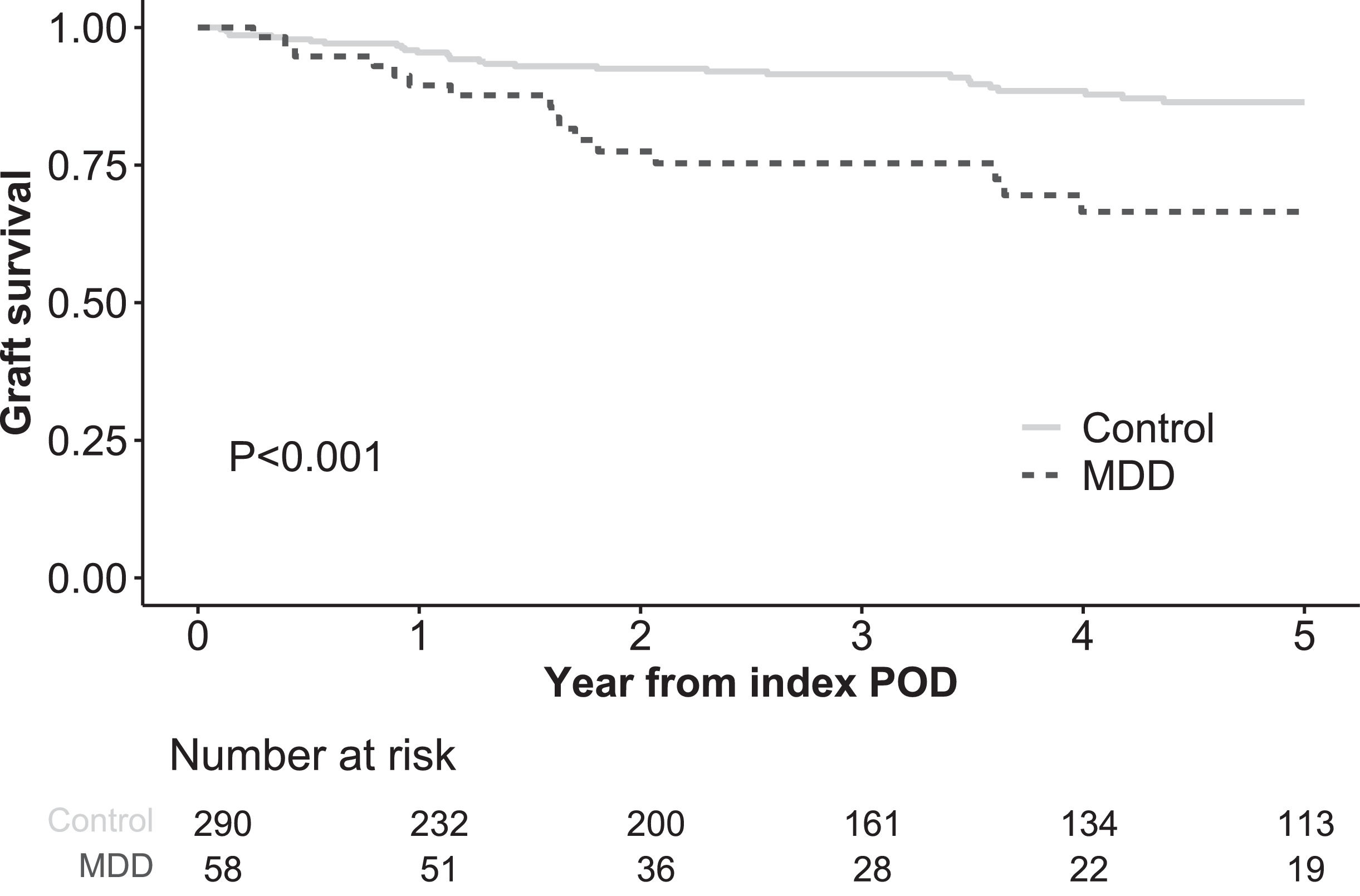

ResultsDuring follow-up post-LT, 58 patients (4.3 %) were newly diagnosed with MDD. The median time from LT to MDD diagnosis was 316 (interquartile range 46–920) days. Patients with MDD had significantly lower graft survival rates than controls at 1, 3, and 5 years after matching (89.5 %, 75.3 %, and 66.5 % vs. 95.5 %, 91.5 %, and 86.4 %, respectively; P = 0.003). Multivariable Cox regression identified de novo MDD as an independent risk factor for reduced graft survival (hazard ratio 2.39, 95 % confidence interval [CI] 1.15–4.98, P = 0.003). Independent risk factors for de novo MDD included female sex (odds ratio [OR] 2.29, 95 % CI 1.16–4.53, P = 0.017), alcoholic liver disease (OR 2.36, 95 % CI 1.16–4.75, P = 0.016), pre-transplant encephalopathy (OR 2.95, 95 % CI 1.49–5.79, P = 0.002), and lower hemoglobin levels (OR 0.85, 95 % CI 0.73–0.98, P = 0.025).

ConclusionsIn our matched population of nested case controls, de novo MDD significantly reduced the survival of LT recipients. Screening and early intervention are required for LT recipients with risk factors for MDD.

Liver transplantation (LT) has emerged as a definitive treatment for patients with end-stage liver disease and unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), resulting in substantial improvements in survival and quality of life [1]. However, the posttransplantation period introduces a new set of challenges, including the onset of psychiatric complications [2]. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is of particular concern owing to its prevalence and impact on LT outcomes. At least 30 % of patients with liver cirrhosis and up to 40 % of LT recipients reportedly experience depressive symptoms [3,4]. Furthermore, the 10-year survival of LT recipients with high depression levels was approximately 23 % lower than that of LT recipients with low depression levels [4].

One hypothesis on how MDD negatively affects LT survival suggests that MDD reduces adherence to immunosuppressive medications and engagement in post-operative clinical follow-up [5,6]. Another social theory proposes that MDD is related to weight gain and reduced physical inactivity, thereby hindering post-operative rehabilitation [7]. Possible biological explanations for MDD include increased activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and glucocorticoid resistance, which may, in turn, increase the risk of graft rejection [8]. Furthermore, serotonin, acting on the 5HT-2b receptor, appears to promote hepatocyte growth, which is another link between MDD and poor outcomes after LT [9]. Similar to non-recipients, the increased incidence of suicide in patients with depression can negatively impact the survival of LT patients [10].

To improve patient outcomes, it is crucial to predict high-risk patient groups for MDD after LT and implement appropriate screening and early intervention [11]. Several risk factors for depression have been reported, including previous depression, younger age, living alone, and unemployment [4,7,12]. However, evidence of de novo MDD post-LT remains poorly investigated. The causes underlying survival and mortality after LT vary considerably among patients, and the timing of MDD onset ranges from short- to long-term. Therefore, an analysis that adjusts for immortal time bias due to time of occurrence is necessary [13]. In the current study, we aimed to analyze the impact of de novo MDD on patient survival following LT and identify potential MDD risk factors among LT recipients.

2Materials and methods2.1Study population and data collectionWe conducted a retrospective analysis of 1385 LTs performed at Severance Hospital, Korea, from July 2005 to December 2022. Exclusion criteria were patients under 18 years of age (n = 129) and those diagnosed with MDD prior to LT (n = 45), resulting in 1350 eligible LT patients. De novo MDD was defined as a new diagnosis made by expert psychiatrists after LT, based on the DSM-IV or DSM-V criteria, depending on the period of diagnosis, regardless of the use of antidepressant medications. The baseline characteristics of the recipients, donors, and transplant factors were retrieved from the institutional LT database. After applying a nested case-control design, various laboratory results on the index post-operative day (POD) for each patient were integrated into the matched cohort. Additional data on the marital status, religion, and primary caregiver post-LT were extracted from the medical records. Data on surgical complications, rejection episodes, and newly initiated dialysis before the index POD were also collected. For the living donor LT (LDLT) subgroup, donor information such as age, sex, relationship with the recipient, and post-operative data, including complications, hospital stay, and readmission after donor hepatectomy, were included.

2.2Nested case-control matchingTo control for the immortal time bias from LT to de novo MDD, patients newly diagnosed with MDD (MDD group) were matched in a 1:5 ratio with controls (control group) using a nested case-control design [14]. Possible controls, i.e., who had not yet been diagnosed with MDD (irrespective of future diagnosis), were randomly sampled at the time points (index POD) corresponding with the MDD diagnosis of the MDD group. To ensure a balanced follow-up duration, the year of LT was mandatorily matched during the sampling process. The type of donor (deceased donor LT or LDLT) was also exactly matched between the groups due to the typically higher pretransplant comorbidities in our cohort, which is attributed to severe regional organ shortages [15]. Patients selected as controls at specific time points could be reused as potential controls at subsequent sampling times for the MDD group, provided they had not been previously diagnosed with MDD. The resulting left-truncated data were followed from the index POD until death, re-transplantation, five years after the sampling time, or June 2023, whichever came first. If control participants were diagnosed with MDD thereafter, they were censored at the time of their first MDD diagnosis.

2.3Statistical methodsData were presented according to normality: categorical variables as numbers (percentages) and continuous variables as medians (interquartile range [IQR]). To compare the MDD group with controls, the chi-square test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used, as appropriate. Graft survival following the index POD was compared between the two groups using the Kaplan–Meier curve and log-rank test to evaluate the impact of MDD on graft survival, thus eliminating immortal time bias. Additionally, the relationship between MDD and graft survival was assessed by performing univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses. Baseline information and graft survival were also compared between LDLT subgroups to determine whether MDD exerted distinct effects on this cohort. Risk factor analyses for de novo MDD were conducted using multivariable logistic regression, including covariates with P < 0.1 in univariable models. Given the number of events in the matched cohort, variables in the multivariable model were selected using the backward stepwise method. All analyses were performed using the R statistical package, version 4.4.1 for macOS (http://cran.r-project.org), with the significance threshold set at P < 0.05.

2.4Ethical statementAll study procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013. The Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital approved this study (4–2024–1092), and the requirement for patient consent was waived owing to its retrospective design.

3ResultsAmong the 1350 eligible LT patients, 58 (4.3 %) were newly diagnosed with MDD during median follow-up of 1528 days (IQR 495–3095) (Fig. 1). The median time from LT to de novo MDD diagnosis was 316 days (IQR 46–920) (Figure S1). Annual incidence of post-LT MDD was 0.8 per 100 person-years. Of those diagnosed with MDD, 38 (65.5 %) used antidepressants, whereas 20 (34.5 %) did not use any antidepressants until the last follow-up. The types of antidepressants primarily used were selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (n = 13), trazodone (n = 14), noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (n = 8), tricyclic antidepressants (n = 2), and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (n = 1).

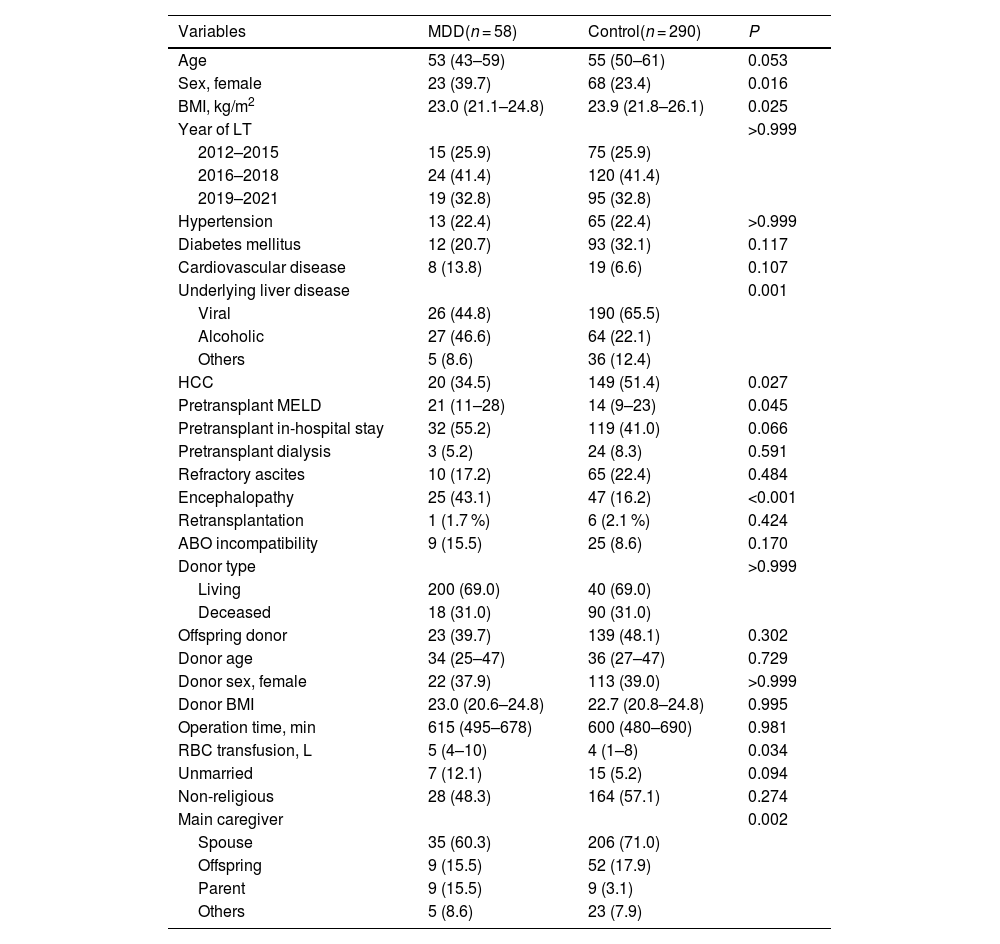

3.1Baseline characteristicsAs shown in Table 1, the age of patients in both the MDD and control groups was comparable (53 [IQR 43–59] years in the MDD group vs. 55 [IQR 50–61] years in the control group, P = 0.053). The proportion of females was higher in the MDD group than in the control group (39.7 % vs. 23.4 %, P = 0.016). Body mass index (BMI) was lower in the MDD group than in the control group (23.0 [IQR 21.1–24.8] kg/m² vs. 23.9 [IQR 21.8–26.1] kg/m², P = 0.025). Both groups had similar rates of hypertension (22.4 % vs. 22.4 %, P > 0.999) and diabetes mellitus (20.7 % vs. 32.1 %, P = 0.117). Underlying liver disease differed significantly between the groups (P = 0.001), with viral causes being more common in the control group (44.8 % vs. 65.5 %) and alcohol-related causes being more prevalent in the MDD group (46.6 % vs. 22.1 %). HCC was less frequent in the MDD group than in the control group (34.5 % vs. 51.4 %, P = 0.027). The pre-transplant model for end-stage liver disease score was significantly higher in the MDD group than in the control group (21 [IQR 11–28] vs. 14 [IQR 9–23], P = 0.045). Both groups had similar rates of pre-transplant dialysis (5.2 % vs. 8.3 %, P = 0.591) and refractory ascites (17.2 % vs. 22.4 %, P = 0.484). However, the occurrence of encephalopathy was significantly higher in the MDD group than in the control group (43.1 % vs. 16.2 %, P < 0.001). Donor age, sex, and BMI showed no significant differences (P = 0.729, P > 0.999, and P = 0.995, respectively). Operative times were comparable between the groups (P = 0.981); however, the volume of red blood cell transfusions was higher in the MDD group than in the control group (5 [IQR 4–10] L vs. 4 [IQR 1–8] L, P = 0.034). The proportion of unmarried individuals was significantly higher in the MDD group than in the control group (12.1 % vs. 5.2 %, P = 0.94). The proportion of non-religious individuals was similar between the groups (48.3 % vs. 57.1 %, P = 0.274). The main caregivers were spouses in the control group (60.3 % vs. 71.0 %), while parents were the more common caregivers in the MDD group (15.5 % vs. 3.1 %, P = 0.002).

Baseline characteristics of patients.

| Variables | MDD(n = 58) | Control(n = 290) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 53 (43–59) | 55 (50–61) | 0.053 |

| Sex, female | 23 (39.7) | 68 (23.4) | 0.016 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.0 (21.1–24.8) | 23.9 (21.8–26.1) | 0.025 |

| Year of LT | >0.999 | ||

| 2012–2015 | 15 (25.9) | 75 (25.9) | |

| 2016–2018 | 24 (41.4) | 120 (41.4) | |

| 2019–2021 | 19 (32.8) | 95 (32.8) | |

| Hypertension | 13 (22.4) | 65 (22.4) | >0.999 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12 (20.7) | 93 (32.1) | 0.117 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 8 (13.8) | 19 (6.6) | 0.107 |

| Underlying liver disease | 0.001 | ||

| Viral | 26 (44.8) | 190 (65.5) | |

| Alcoholic | 27 (46.6) | 64 (22.1) | |

| Others | 5 (8.6) | 36 (12.4) | |

| HCC | 20 (34.5) | 149 (51.4) | 0.027 |

| Pretransplant MELD | 21 (11–28) | 14 (9–23) | 0.045 |

| Pretransplant in-hospital stay | 32 (55.2) | 119 (41.0) | 0.066 |

| Pretransplant dialysis | 3 (5.2) | 24 (8.3) | 0.591 |

| Refractory ascites | 10 (17.2) | 65 (22.4) | 0.484 |

| Encephalopathy | 25 (43.1) | 47 (16.2) | <0.001 |

| Retransplantation | 1 (1.7 %) | 6 (2.1 %) | 0.424 |

| ABO incompatibility | 9 (15.5) | 25 (8.6) | 0.170 |

| Donor type | >0.999 | ||

| Living | 200 (69.0) | 40 (69.0) | |

| Deceased | 18 (31.0) | 90 (31.0) | |

| Offspring donor | 23 (39.7) | 139 (48.1) | 0.302 |

| Donor age | 34 (25–47) | 36 (27–47) | 0.729 |

| Donor sex, female | 22 (37.9) | 113 (39.0) | >0.999 |

| Donor BMI | 23.0 (20.6–24.8) | 22.7 (20.8–24.8) | 0.995 |

| Operation time, min | 615 (495–678) | 600 (480–690) | 0.981 |

| RBC transfusion, L | 5 (4–10) | 4 (1–8) | 0.034 |

| Unmarried | 7 (12.1) | 15 (5.2) | 0.094 |

| Non-religious | 28 (48.3) | 164 (57.1) | 0.274 |

| Main caregiver | 0.002 | ||

| Spouse | 35 (60.3) | 206 (71.0) | |

| Offspring | 9 (15.5) | 52 (17.9) | |

| Parent | 9 (15.5) | 9 (3.1) | |

| Others | 5 (8.6) | 23 (7.9) |

BMI, body mass index; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; LT, liver transplantation; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; RBC, red blood cell; MDD, major depressive disorder.

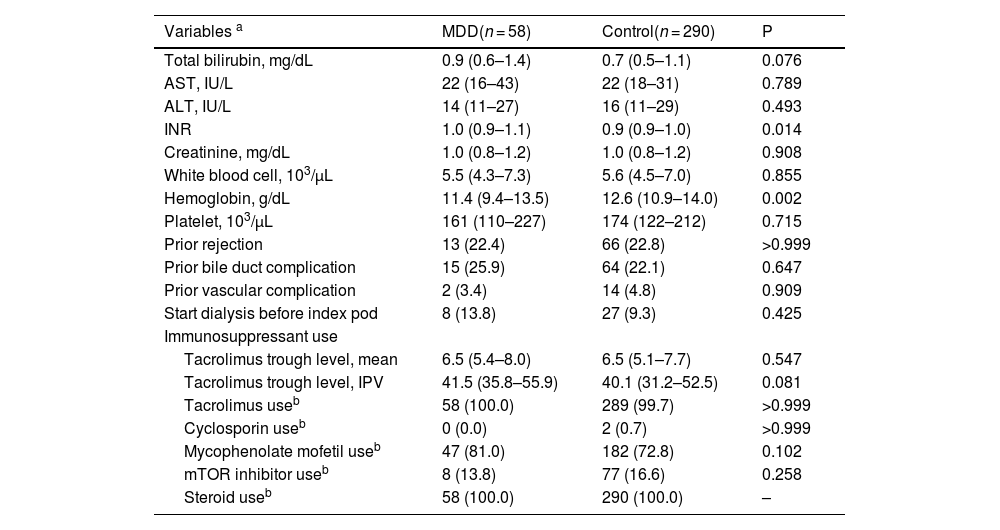

Several laboratory and clinical parameters were compared with the matched POD indices (Table 2). Levels of total bilirubin (0.9 mg/dL [IQR 0.6–1.4] vs. 0.7 mg/dL [IQR 0.5–1.1], P = 0.076), aspartate aminotransferase (22 IU/L [IQR 16–43] vs. 22 IU/L [IQR 18–31], P = 0.789), and alanine aminotransferase were comparable (14 IU/L [IQR 11–27] vs. 16 IU/L [IQR 11–29], P = 0.493) between two groups. The international normalized ratio was higher in the MDD group (1.0 [IQR 0.9–1.1] vs. 0.9 [IQR 0.9–1.0], P = 0.014) than that in the control group. The hemoglobin level at index POD was significantly lower in the MDD group than in the control group (11.4 g/dL [IQR 9.4–13.5] vs. 12.6 g/dL [IQR 10.9–14.0], P = 0.002), whereas white blood cell and platelet counts were similar between the groups. The rates of prior rejection (22.4 % vs. 22.8 %, P > 0.999), bile duct complications (25.9 % vs. 22.1 %, P = 0.647), and vascular complications (3.4 % vs. 4.8 %, P = 0.909) were similar between the groups. The proportion of patients who started dialysis before the index POD was comparable between the two groups (13.8 % vs. 9.3 %, P = 0.425). Regarding immunosuppression, mean tacrolimus trough level and intrapatient variability were similar between groups. The use of each immunosuppressive drugs was similar between the MDD and control groups.

Information at index POD.

| Variables a | MDD(n = 58) | Control(n = 290) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | 0.7 (0.5–1.1) | 0.076 |

| AST, IU/L | 22 (16–43) | 22 (18–31) | 0.789 |

| ALT, IU/L | 14 (11–27) | 16 (11–29) | 0.493 |

| INR | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 0.9 (0.9–1.0) | 0.014 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.908 |

| White blood cell, 103/μL | 5.5 (4.3–7.3) | 5.6 (4.5–7.0) | 0.855 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 11.4 (9.4–13.5) | 12.6 (10.9–14.0) | 0.002 |

| Platelet, 103/μL | 161 (110–227) | 174 (122–212) | 0.715 |

| Prior rejection | 13 (22.4) | 66 (22.8) | >0.999 |

| Prior bile duct complication | 15 (25.9) | 64 (22.1) | 0.647 |

| Prior vascular complication | 2 (3.4) | 14 (4.8) | 0.909 |

| Start dialysis before index pod | 8 (13.8) | 27 (9.3) | 0.425 |

| Immunosuppressant use | |||

| Tacrolimus trough level, mean | 6.5 (5.4–8.0) | 6.5 (5.1–7.7) | 0.547 |

| Tacrolimus trough level, IPV | 41.5 (35.8–55.9) | 40.1 (31.2–52.5) | 0.081 |

| Tacrolimus useb | 58 (100.0) | 289 (99.7) | >0.999 |

| Cyclosporin useb | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) | >0.999 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil useb | 47 (81.0) | 182 (72.8) | 0.102 |

| mTOR inhibitor useb | 8 (13.8) | 77 (16.6) | 0.258 |

| Steroid useb | 58 (100.0) | 290 (100.0) | – |

: use of each immunsuppressants was defined as prescription at over 50 % of post-transplant days before index POD

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ICU, intensive care unit; INR, international normalized ratio; IPV, intrapatient variability; POD, post-operative day; MDD, major depressive disorder; LT, liver transplantation.

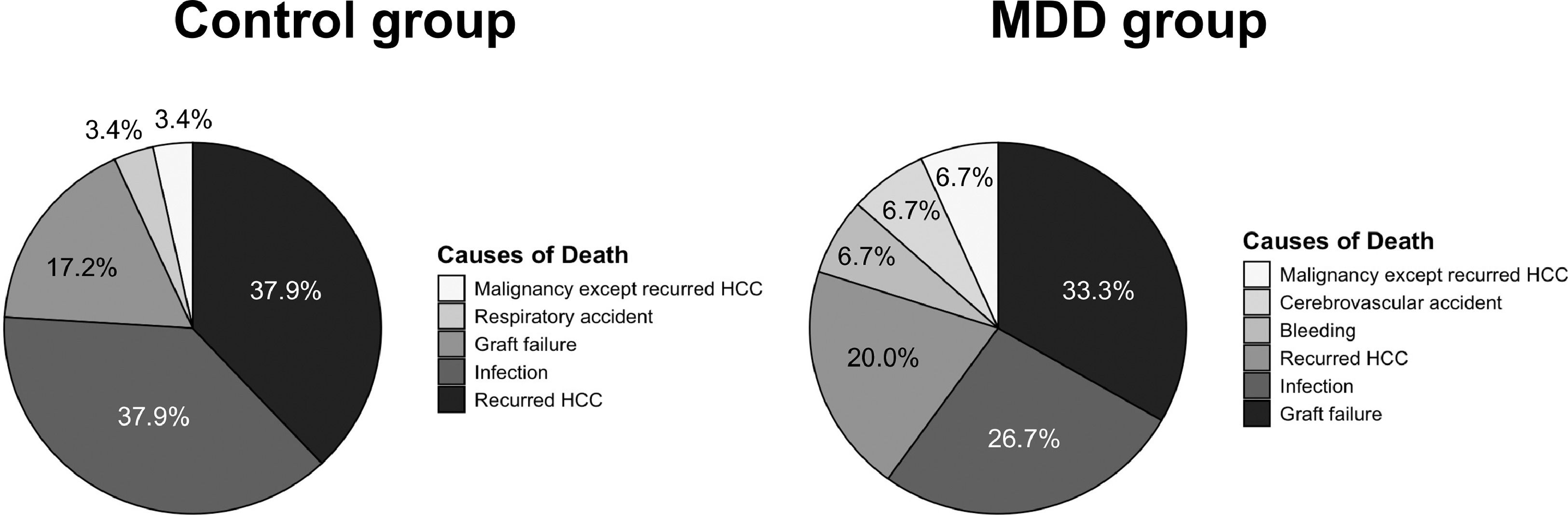

In the Kaplan–Meier analysis, graft survival (death or re-LT) following the index POD was significantly lower in the MDD group than in the control group, with 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates of 89.5, 75.3 %, and 66.5 %, respectively, versus 95.5, 91.5, and 86.4 % in the no-MDD group (P < 0.001, Fig. 2). Both univariate and multivariate Cox regression models identified post-LT de novo MDD as an independent risk factor for graft survival in the matched cohort, with a hazard ratio of 2.39 (95 % confidence interval [CI] 1.15–4.98, Table S1). In the MDD group, graft failure was the most common cause of death (n = 5, 33.3 %), followed by infection (n = 4, 26.7 %) and recurrent HCC (n = 3, 20.0 %, Fig. 3). In the control group, the most common causes of death were recurrent HCC (n = 11, 37.9 %) and infection (n = 11, 37.9 %), followed by graft failure (n = 5, 17.2 %). Among patients with graft failure, the most common cause was patient death with a functioning graft, accounting for 56.2 % in the MDD group and 82.8 % in the control group (Table S2). The second most common cause in the MDD group was alcohol recidivism (18.8 %), compared to only one case (3.4 %) in the control group. Among patients with underlying alcoholic liver disease, alcohol recidivism was the underlying cause of graft failure in three of 27 patients in the MDD group (11.1 %) and in one of 64 patients (1.6 %), although the difference was not significant (P = 0.142).

Among the MDD group (38 with antidepressant medication, 20 without medication), graft survival did not differ, regardless of the use of antidepressants (P = 0.840, Figure S2). In the LDLT subcohort, there were no significant differences in living donor information, including donor age, sex, relationship, donor complications, and readmission (Table S3). Graft survival was significantly lower in the MDD group than in the control eighter in LDLT patients (72.1 % vs. 90.0 %, P = 0.002, Figure S3)

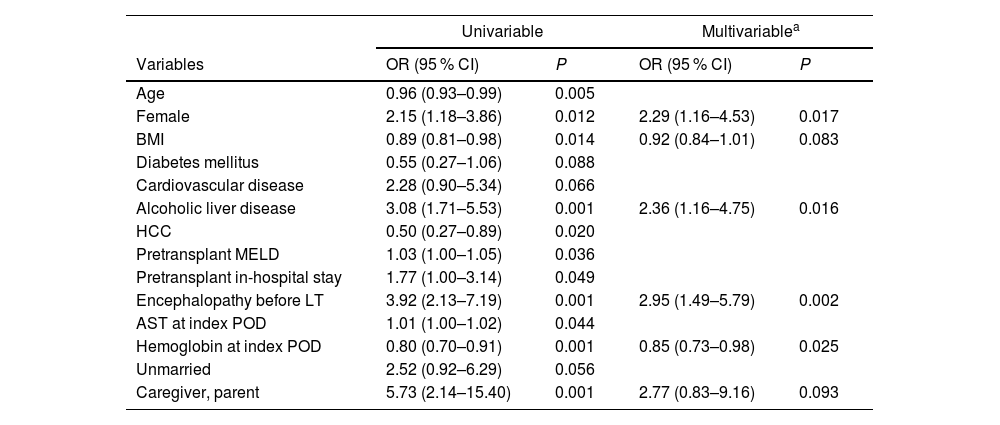

3.5Risk factors for de novo MDDIn both univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses (Table 3), the independent risk factors for MDD following LT were identified as female sex (odds ratio [OR] 2.29, 95 % CI 1.16–4.53), alcoholic liver disease (OR 2.36, 95 % CI 1.16–4.75), and pre-transplant encephalopathy (OR 2.95, 95 % CI 1.49–5.79). Among the laboratory values at the index POD, serum hemoglobin showed a significant inverse relationship with MDD (OR 0.85, 95 % CI 0.73–0.98). The MDD group had significantly lower pre-LT hemoglobin than the control group (10.9 ± 2.2 vs. 10.0 ± 1.9, P = 0.005), with a similar trend observed during the follow-up period (Figure S4). Based on risk factor analyses in subgroups according to recipient sex, hemoglobin showed significant association in male patients (OR 0.82, 95 % CI 0.69–0.97) and marginal association in female patients (OR 0.79, 95 % CI 0.61–1.02, Table S4)

Risk factors for de novo MDD after LT.

| Univariable | Multivariablea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR (95 % CI) | P | OR (95 % CI) | P |

| Age | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | 0.005 | ||

| Female | 2.15 (1.18–3.86) | 0.012 | 2.29 (1.16–4.53) | 0.017 |

| BMI | 0.89 (0.81–0.98) | 0.014 | 0.92 (0.84–1.01) | 0.083 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.55 (0.27–1.06) | 0.088 | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 2.28 (0.90–5.34) | 0.066 | ||

| Alcoholic liver disease | 3.08 (1.71–5.53) | 0.001 | 2.36 (1.16–4.75) | 0.016 |

| HCC | 0.50 (0.27–0.89) | 0.020 | ||

| Pretransplant MELD | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) | 0.036 | ||

| Pretransplant in-hospital stay | 1.77 (1.00–3.14) | 0.049 | ||

| Encephalopathy before LT | 3.92 (2.13–7.19) | 0.001 | 2.95 (1.49–5.79) | 0.002 |

| AST at index POD | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.044 | ||

| Hemoglobin at index POD | 0.80 (0.70–0.91) | 0.001 | 0.85 (0.73–0.98) | 0.025 |

| Unmarried | 2.52 (0.92–6.29) | 0.056 | ||

| Caregiver, parent | 5.73 (2.14–15.40) | 0.001 | 2.77 (0.83–9.16) | 0.093 |

Model was established using the backward stepwise method.

Only variables with a P value <0.1 in the univariable analysis are presented.

AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BMI, body mass index; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; LT, liver transplantation; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; POD, post-operative day; MDD, major depressive disorder; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

The improved prognosis following LT has shifted the focus toward the mental health of LT recipients [16]. MDD, a common psychological problem in LT recipients, can markedly impact medication adherence to immunosuppressants and eventually affect overall survival and quality of life. Therefore, identifying the risk factors for MDD and implementing appropriate clinical interventions are essential for improving the prognosis and enhancing the quality of life of LT recipients. In the current study, we detected an independent association between de novo MDD and LT survival, along with associated risk factors, efficiently controlling for immortal time bias via a nested case-control design.

Cross-sectional studies examining depressive symptoms have reported that 30–40 % of LT recipients experience depressive symptoms [4]. However, in this study, the incidence of de novo MDD was 4.3 %. In a Korean population-based study, depression was the most common psychological disease during the post-LT period, with a prevalence of 37.5 %. However, among patients without pre-LT depression, only 60 of 3758 (approximately 1.6 %) were diagnosed with a depressive disorder post-LT [2]. The age-standardized prevalence of MDD among Korean adults was reported to be 5.6 % as of 2016 [17]. Additionally, the incidence of MDD in patients with chronic liver disease has been reported as 7.54 per 100 person-years in a population-based study utilizing claims data [18]. However, direct comparison with the incidence reported in our study is limited, as our study employed diagnostic criteria such as DSM-IV or V and diagnoses were confirmed by psychiatrists. Furthermore, Given that the follow-up period in this study was longer than that in the population-based study, and the data from this single center were more precise, the incidence of MDD in our population appears to be a reasonable figure. It is important to note that this study did not screen all the patients who were not referred for psychiatric assessment using a depression scale.

Hypotheses for the reduced LT survival associated with depression include decreased adherence to treatment and management, including immunosuppressants, and reduced physical activity [5,6]. However, given the retrospective nature of this study, the hypotheses were difficult to analyze. Alcohol consumption is currently the leading cause of liver disease requiring liver transplantation, surpassing viral hepatitis in the United States [16]. Post-LT alcohol recidivism rates vary widely depending on the definition used, ranging from 10 to 50 % [19]. In South Korea, although the rate of post-transplant alcohol recidivism is lower than that in Western countries, studies indicate a rate of approximately 25 %, which remains a notable cause of graft failure [20]. Although depression is commonly associated with patients with alcoholic liver disease, a meta-analysis detected no significant correlation between depression and alcohol recidivism in LT recipients [21]. However, the same study also identified psychiatric disease as a risk factor for alcohol recidivism, underscoring the importance of post-LT mental health management. The findings of this study indicate that alcoholics are at a higher risk of depression, suggesting that managing depression in these patients is crucial as it can substantially impact the likelihood of alcohol recidivism and overall survival after LT.

In the current study, female sex was identified as a risk factor for MDD following LT. In the general population, it is well known that females have twice the prevalence of depression than males [10]. These differences can be attributed to a combination of biological, hormonal, and social factors that adversely impact females [22]. In terms of treatment efficacy, female patients generally respond better to antidepressants but are more likely to experience side effects. Conversely, males are less likely to report depressive symptoms and seek treatment, potentially leading to an underestimation of their depression rates [23]. Understanding these sex-based disparities is crucial for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies tailored to the specific needs of LT recipients of each sex.

Hepatic encephalopathy is an important complication occurring in 40–70 % of patients with liver cirrhosis and is a crucial factor influencing outcomes after LT [24,25]. Hepatic encephalopathy and depression exhibit several overlapping clinical features, including psychomotor and cognitive impairment. This overlap complicates the co-diagnosis of both conditions and makes it challenging to distinguish their symptoms as distinct or different expressions of the same disorder [26]. Additionally, attempts have been made to clarify the relationship between hepatic encephalopathy and depression by linking both conditions to the gut microbiota-brain axis [27,28]. However, clinical evidence of the relationship between hepatic encephalopathy and depression remains insufficient, with some studies reporting negative results [29]. In the current study, pre-LT encephalopathy was identified as a significant risk factor for the development of de novo depression, which is a crucial insight supporting the clinical correlation between these two conditions.

The inverse relationship between hemoglobin levels and de novo depression is an interesting finding of this study. Previous studies have shown that anemia is closely associated with depressive symptoms, particularly among pregnant women [30]. In older adults, untreated anemia has been linked to a 2.6-fold increase in the risk of depression [31]. Multiple population-based studies have revealed a robust association between anemia and depression [32,33]. Possible mechanisms include reduced tissue oxygenation, diminished physical performance due to anemia, and changes in monoamine synthesis caused by malnutrition, all of which may influence depression [32]. In the matched population of this study, the MDD group demonstrated persistently lower hemoglobin levels post-LT than the control group, suggesting that correcting anemia may be necessary to prevent depression in patients with LT. However, given the presence of negative reports on the causality between anemia and depression, caution is needed when interpreting these results, and further studies are warranted [34].

Limitations of this study include its retrospective and single-center nature. However, we minimized time-related bias up to the occurrence of depression using nested case-control matching. Another limitation is that the diagnosis of MDD was limited to the diagnosis and description of antidepressants by psychiatrists. Evaluation metrics, such as the Beck Depression Inventory score, were unavailable; hence, treatment intention could not be fully assessed. Finally, the primary reported hypotheses for the reduced survival of patients with depression, such as lower adherence and decreased physical activity, were challenging to confirm owing to the retrospective nature of the study. The impact of socioeconomic status on compliance, alcohol recidivism, and the development of MDD in LT patients requires further investigation through future studies.

5ConclusionsThe findings of this study revealed that the development of de novo MDD notably decreased LT survival rates, with control of immortal time bias achieved through a nested case-control design. Additionally, female sex, alcoholic liver disease, pre-transplant encephalopathy, and reduced hemoglobin levels were identified as independent predictors of MDD. We recommend psychiatric evaluation and intervention for LT recipients with these risk factors.

Author contributionsD.G.K. had full access to all aspects of the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis; Y.J.Y. and D.G.K. participated in the research design; E.K.M., J.G.L., D.J.J. and M.S.K. participated in the performance of the research; Y.J.Y., M.K., H.H.K, E.K.M. and participated in the data acquisition; Y.J.Y., H.H.K and D.G.K. participated in the statistical analysis; Y.J.Y. and D.G.K. Participated in the writing of the paper; D.G.K. supervised the study process. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.