The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a greater incidence of alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) and simultaneously magnified health-related inequalities. We evaluated the impact of race and ethnicity on ALD-related hospitalizations in Brazil.

Materials and MethodsAn interrupted time series analysis was used to estimate ALD-related hospitalization in public hospitals in Brazil. Monthly hospitalization rates for 34 consecutive months before and after the point of interruption (March 2020) were calculated using the Sistema de Informações Hospitalares database across four ethnic groups: Black, Pardo, Black, and Pardo combined, and Others (White and Unknown Ethnicity).

ResultsA total of 84,787 ALD-related hospitalizations were recorded during the study period. The mean age of hospitalized patients was 53 years (SD=12.5); 83.6% were male. Immediately after the start of the pandemic, there was a statistically significant decrease in monthly ALD-related hospitalization rates for the whole population and for all ethnic groups. Subsequently, compared to pre-pandemic rates, there was a statistically significant trend increase in the referred hospitalization rates for the total population (0.065, 95% CI= 0.045 to 0.085, p<0.01), black population (0.0028, 95% CI= 0.006 to 0.050, p<0.05), pardo population (0.077, 95% CI= 0.063 to 0.090, p<0.01), and for black and pardo combined population (0.066, 95% CI= 0.053 to 0.079, p<0.01); however, the increase in hospitalization rates among the Others population (0.059, 95% CI= -0,014 to 0.133, p>0.1) was not statistically significant.

ConclusionsThe pandemic impacted ALD-related monthly hospitalization rates and disproportionately impacted Black and Pardo populations in Brazil.

Alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) represents a major global health burden, encompassing a spectrum of liver injuries caused by chronic alcohol consumption, ranging from simple steatosis to more severe forms such as alcoholic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma [1,2]. Recent global estimates indicate that alcohol use was the seventh leading risk factor for both deaths and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) in 2016, accounting for 2.2% of age-standardized female deaths and 6.8% of age-standardized male deaths [3]. The World Health Organization's Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health estimates that approximately 2.3 billion people worldwide are current drinkers [4]. Global alcohol per capita consumption rose from 5.5 liters of pure alcohol in 2005 to 6.4 liters in 2016, with projections indicating a further increase to 7.6 liters by 2030 [5]. This trend is particularly concerning given the direct relationship between alcohol consumption and the risk of developing ALD.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated this issue worldwide, which is illustrated by the rise in alcohol-associated hepatitis [6], ALD-related hospitalizations [7], and ALD-related mortality [8]. Possible explanations are the delay in ALD care and the rise in alcohol consumption. In the early pandemic, a decrease in ALD-related emergency department (ED) presentations due to fear of COVID-19 exposure [9] and reduced access to outpatient hepatology clinics were seen, possibly preventing earlier disease diagnosis and decompensation detection. [10] Numerous countries reported increased alcohol use during the pandemic [11,12]. The rise in alcohol consumption was attributed to pandemic-related psychological distress, isolation [13], financial insecurity [14], and unemployment [15]. Also, decreased access to addiction treatment services led to increased alcohol relapses in those with alcohol use disorder [16]. The consequences have been extreme. As of 2020, ALD has become the number one indication for liver transplant in the US and accounts for more liver transplant waitlist candidates than other etiologies combined [17].

Racial and ethnic inequities in health care existed before the pandemic, but the pandemic only further magnified these and uncovered more. Many studies from various countries have highlighted racial inequities impacting different medical conditions during the pandemic. Studies suggest the pandemic has amplified racial inequities, resulting in poorer health outcomes for minorities. For example, a US observational study reported that patients belonging to racially and ethnically minoritized groups had lower odds of obtaining a liver transplant during the pandemic [18]. Another study, using a US national healthcare database, reported that during the pandemic, in-hospital ALD-related mortality was highest for Black individuals, and ALD was more prevalent in American Indian/Alaska Native individuals [19]. The US is the only country that has reported on the pandemic's impact on ALD-related racial inequities– no other country data has reported on ALD-related racial inequities.

Brazil is a unique setting in which to study inequities. Despite being one of the most economically unbalanced countries in the world, healthcare in Brazil is a constitutional right. [20,21] Brazil's national healthcare system, the Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde), provides all Brazilians and legal residents free healthcare. By the number of users and treatment centers, it is the world's largest government-run public health care system. Still, healthcare-related racial inequities exist in Brazil. A recent study analyzing Brazil's mortality database found that excess mortality among black/brown individuals was 26.3% higher during the pandemic than among White individuals [22]. Using its publicly available health databases, the Sistema de Informações Hospitalares (SIH/DATASUS) and the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), we analyzed monthly ALD-related hospitalization rates in public hospitals to better understand the pandemic's impact on ALD and assess for racial inequities.

2Materials and methods2.1Data descriptionThis study analyzed monthly ALD-related hospitalizations using admission data from SIH/DATA SUS. SIH/DATASUS database contains all individual inpatient data for any hospital stays at a public hospital [23]. SIH/DATASUS databases use the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) [24]. SIH/DATASUS database contains admission data from approximately 2300 hospitals in five regions, 26 states, and one federal district. Since SIH/DATASUS only provides inpatient data, we used IBGE to obtain total population data for self-identified race/ethnicity, which was necessary to calculate the monthly ALD-related hospitalization rate.

2.2Racial and ethnic dataIBGE is the federal government institution responsible for the census in Brazil. They collect data on a myriad of characteristics of the population, including racial and ethnic identification. In the questionnaire used by IBGE, [25] there is a section used for racial and ethnic self-identification. The free translation for this section is: your race or color is: (a sua cor ou raça é:) followed by the options white (branca), black (preta), yellow (amarela), pardo and Indigenous (Indígena). 'pardo' is a term unique to Brazil, reflecting a complex and somewhat contested definition of a mixture of ethnicities that emerged during the country's early history. Due to its distinct cultural and historical significance, a direct translation to English fails to convey its full meaning. Therefore, in our article, we retain the original term 'pardo' to preserve the accuracy, cultural value, and contextual integrity of this category. The ethnic categories reported on SIH/DATASUS follow the same format as the questionnaire from IBGE.

2.3Data extractionData was collected on May 3, 2022. We extracted all individual hospital admission data using Python 3.10.11 script and PySUS library. The dataset contained the following variables: primary diagnosis, race/ethnicity, assigned gender at birth, date of birth, patient age, city of admission, county of admission, state of admission, date of admission, and length of hospital stay. To identify ALD-related hospitalizations, we used ICD-10 codes K70.0 through K70.9. These codes encompass the full spectrum of alcohol-associated liver diseases and ensure that we captured all relevant cases of ALD in our analysis.

2.4Data cleaning and deduplicationThe raw data originated from admission billing authorizations. The dataset does not look at unique data. Multiple billing authorizations would sometimes be generated for the same admission, especially if the patient was readmitted or had an extended hospital stay. To address this, we generated a unique key incorporating various variables. [26] This key was used to deduplicate the dataset, ensuring our findings avoid repeated records.

2.5Outcome measuresThe primary outcome of our study was the monthly ALD-related hospitalization rate. To calculate monthly ALD-related hospitalization rates for black and pardo populations, we divided each race's individual month's total ALD-related hospitalizations (obtained from SIH/DATASUS) by the total population of the same race (obtained from IBGE). We calculated individual monthly ALD-related hospitalizations for the other population group (white and unknown ethnicity populations) by subtracting ALD-related hospitalizations for the black and pardo combined population from total ALD-related hospitalizations. To obtain monthly ALD-related hospitalization rates for the Others population, we divided its individual month's total ALD-related hospitalization by the total Others population (obtained from IBGE by subtracting black and pardo combined population from the total population).

2.6COVID-19 pandemic in BrazilThe COVID-19 pandemic reached Brazil in January 2020; the first significant surge of cases occurred in March 2020. [27] Following March 11, 2020, when the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 as a global pandemic [28], all Brazilian states implemented distancing measures [29]. For our analysis, March 2020 was used as the start date of the.

2.7Interrupted time seriesWe created an interrupted time series to estimate the pandemic's effect on monthly ALD-related hospitalization rates. The observation period was from May 2017 to December 2022. March 2020 was made a point of interruption. Thirty-four consecutive monthly ALD-related hospitalization rates were calculated before March 2020, and 34 consecutive monthly ALD-related hospitalization rates were calculated after. To study changes associated with race, using the race/ethnicity variable, aside from the total population, we categorized all ALD-related hospitalizations into four groups: black, pardo, black and pardo combined, and Others group [30].

2.8Statistical analysesThe segmented regression model is represented by the following equation:

In this analysis, Yt represents the hospitalization rate at time t, with time ranging from the beginning to the end of the observation period (March 2017 to December 2022). The intervention variable designates whether time t occurs before (intervention = 0) or after (intervention = 1) the start of COVID-19 restrictions. The model includes β0, which estimates the initial hospitalization rate at t0. β1 represents the hospitalization trend before introducing the COVID‐19 measures, β2 is the immediate change in hospitalization rate after the measures are implemented, and β3 reflects the difference in trends before and after establishing COVID-19 measures. The sum of β1 and β3 estimates the post-COVID. [31] Autocorrelation was examined by the Breusch-Godfrey test, and the Newey–West standard error was used to account for autocorrelation. All statistical analyses were performed using R Software version 4.2.3.

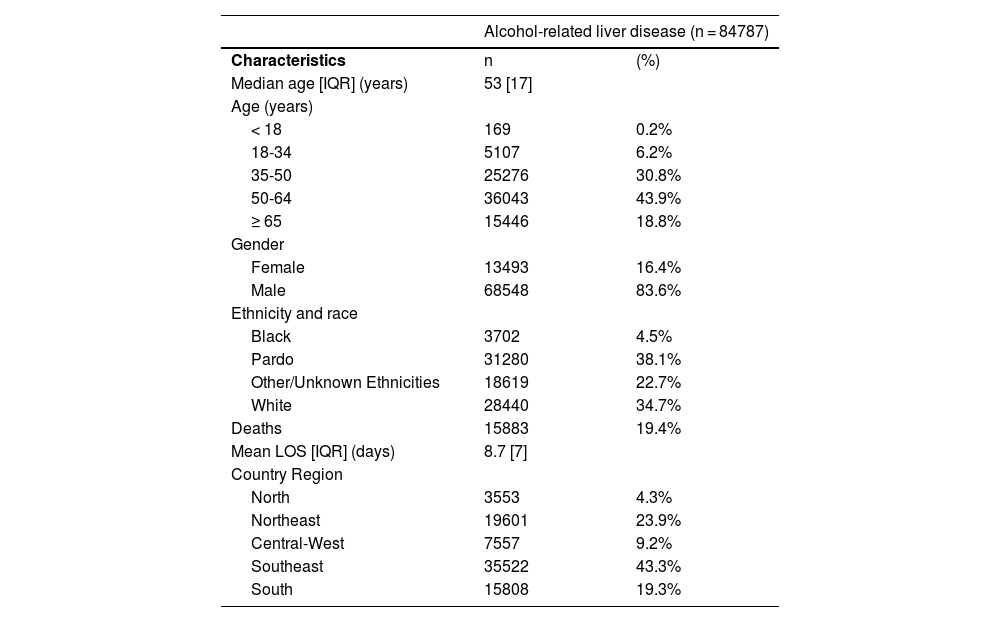

3ResultsA total of 84,787 ALD-related hospitalizations occurred between May 2017 and December 2022. Patients had a mean age of 53 years (SD=12.5). The mean length of hospital stay was 8.6 days (SD=9.03). 83.6% of patients were male, and 38% were pardo. Most ALD-related hospitalizations were seen in the Southeast region at 43.3%. See Table 1 for further details on patient characteristics.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of ALD admissions in Brazil's public hospitals from May 2017 to December 2022.

LOS: Length of stay

Before March 2020, there was a statistically significant decrease in monthly ALD-related hospitalizations for the total population (-0.014, 95% CI= -0.024 to -0.005, p<0.05), the Black population (-0.019, 95% CI = -0.035 to -0.004, p<0.05), and the Others populations (-0.029, 95% CI= -0.042 to -0.015, p<0.01). Pardo (0.004, 95% CI= -0.004 to 0.011) and black and pardo combined population (0.001, 95% CI= -0.008 to 0.007) were not statistically significant.

During March 2020, there was an immediate, significant decrease in monthly ALD-related hospitalization rates for three consecutive months. There was a statistically significant decrease in monthly ALD-related hospitalizations rate for the total population (-0.941, 95% CI= -1.310 to -0.571, p<0.01), pardo population (-0.871, 95% CI= -1.146 to -0.595, p<0.01), black and pardo combined population (-0.713, 95% CI= -1.008 to -0.419, p<0.01), and the others population (-1.329, 95% CI= -2.061 to -0.596, p<0.01). Changes in monthly ALD-related hospitalization were not statistically significant in the black population (-0.103, 95% CI= -0.649 to 0.442).

Despite this immediate decrease in monthly ALD-related hospitalization rates, there was a statistically significant trend increase in monthly ALD-related hospitalization rates for the total population (0.065, 95% CI= 0.045 to 0.085, p<0.01), pardo population (0.077, 95% CI= 0.063 to 0.090, p<0.01), black population (0.0028, 95% CI= 0.006 to 0.050, p<0.05), black and pardo combined population (0.066, 95% CI= 0.053 to 0.079, p<0.01) compared to pre-pandemic. The others population (0.059, 95% CI= -0.014 to 0.133, p>0.1) did not show significant trend change. Overall, there was a disproportionate increase in monthly ALD-related hospitalization rates in racial minorities; the pardo group experienced the largest increase. See Fig. 1 for a comparative overview between populations.

Lastly, the in-hospital mortality rate for the entire population during our observation period was 19.4%. Analysis according to population groups showed that in-hospital mortality was highest in the Black population at 19.49%. In-hospital mortality of pardo and other populations were respectively 18.80% and 17.30%.

4DiscussionThis study is the first to investigate the impact of the pandemic on monthly ALD-related hospitalization rates and ALD-related racial inequities in Brazil's public health system. Compared to pre-pandemic hospitalization rates for ALD, this study showed a statistically significant increase in monthly ALD-related hospitalization rates in the total population, black population, and pardo population; furthermore, for these population groups, the rates progressively increased for 31 months until the end of our observation period. In contrast, the Others population did not show a significant trend change. These results are consistent with those of previous studies. For example, a US study reported that Black individuals are less likely than White individuals to receive living donor transplantation despite the black population having higher rates of liver transplant graft failures [32]. In addition, an observational cohort study from the US showed that Black and Hispanic patients with chronic liver disease are disproportionately represented in patients with chronic liver disease who acquire COVID-19 [33]. Thus, the pandemic has disproportionately magnified racial inequities in individuals with severe liver disease.

Three distinct phases in monthly total ALD-related hospitalization rates emerged in this study. The first phase was a statistically significant decrease in total monthly ALD-related hospitalization rates before March 2020. A plausible explanation is Brazil's decrease in overall alcohol consumption [34], which could be attributed to policies enacted by Brazil's federal government over the last decade. For instance, the federal government implemented the lei seca ("dry law"), a zero-tolerance law (ZTL), which prohibited drivers from having any measurable blood alcohol content (BAC). This policy was enacted in 2008 and reinforced in 2012 and 2016. If a driver is found to have any BAC up to 0.06%, the driver is to have their car seized, pay a fine, and have their license suspended for 12 months; anything greater than 0.06% is considered a criminal offense and can lead to jail time [35,36]. Studies have shown that ZTL not only reduces alcohol-related car accidents but also can reduce overall alcohol consumption. A recent German survey study investigating behavior effects after the government enacted a ZTL found that the law reduced alcohol consumption among young adults [37]. Brazil and Germany are two of the roughly fifteen percent of countries that have enacted a ZTL for at least novice drivers. In addition to ZTL, Brazil's federal government enacted Law 13.106 in 2015, making it a crime to offer alcoholic beverages to minors [38]. Addressing alcohol use at a national level could explain the reduction in overall alcohol consumption, indirectly reducing ALD-related hospitalizations.

The second phase was a statistically significant decrease in total monthly ALD-related hospitalization rates for three consecutive months after March 2020. This decrease could be explained by reduced access to non-COVID health services and patients fearing to come to the hospital because of fear of contracting COVID-19; both factors were seen to impact other severe medical conditions as well. A Brazilian retrospective chart review examining appointment data from a major cancer center between March 2020 and June 2020 found a 42% reduction in first-time appointments compared to the same period in the previous year. Unfortunately, the reduction in access probably delayed the detection of ALD decompensation, leading to the next phase. A US retrospective cohort study that examined weekly hospitalization counts for the first few months of the pandemic found that cirrhosis-related hospital admissions declined by 50%, but patients who were hospitalized had higher MELD-NA scores, suggesting delays in presenting to the hospital [39].

It's important to note that the increasing trend in ALD-related hospitalizations observed in our study aligns with recent research highlighting alarming rises in liver disease prevalence, particularly among younger populations. Tapper and Parikh (2018) observed that people aged 25-34 years experienced the highest average annual increase in cirrhosis-related mortality (10.5%) during 2009-2016, driven entirely by alcohol-related liver disease [40]. Mellinger et al. (2018) reported that the mean age at alcoholic cirrhosis diagnosis was 53.5 years, with 32% being women, indicating a shift towards younger populations [41]. Doycheva et al. (2017) found a sharp increase in chronic liver disease prevalence among adolescents and young adults (ages 15-39), from 12.9% in 1988-1994 to 28.5% in 1999-2004 [42]. These findings suggest that the pandemic may have exacerbated pre-existing trends in ALD prevalence among younger adults. This emerging pattern of earlier onset ALD could have significant implications for future healthcare needs and emphasizes the importance of early intervention and prevention strategies targeting younger age groups.

The third phase was a statistically significant trend increase in total monthly ALD-related hospitalization rates until the end of the observation period. The last month included in our analysis was December 2022. These results are in line with other international studies, including studies from Australia [43], India [44] and the US; all countries where an increase in alcohol consumption was also reported.

Interpreting this study's findings within the broader context is important. Brazil has extreme income and social inequalities; the richest five percent have the same income as the remaining 95 percent [45]. This imbalance contributes to health-related racial inequities. [46] Despite recent progress in extending social protections, such as universal health coverage and expanding community-based primary care, racial inequities persist. [47,48] In a nationally representative cross-sectional survey study, "Non-white" individuals were more likely to underutilize the national healthcare system than White individuals; factors associated with underutilization included lower education and lower social class. [49] The authors pointed to barriers to access and uneven supply of services as reasons for healthcare underutilization. The consequences of healthcare underutilization can be dire. Nowhere was this more clearly seen than in Brazil's North region in 2020, which had the highest standardized COVID-19 death rate, largely attributed to a lack of ICU beds and ICU physicians; [50] a majority of Black/Brown individuals live in the North and Northeast Brazil [51]. Another cross-sectional study completed in Brazil showed that the black population had higher rates of multimorbidity, lower rates of primary healthcare utilization, and higher risk of death than the White population [52]. Patients who belong to racial and ethnic minority groups would like better healthcare access, and they self-report poor health [46]. In another nationally representative cross-sectional survey study, black individuals reported facing greater challenges in accessing healthcare. [53,54] black and brown individuals scored statistically significantly poorer scores in the self-rated health measure, a subjective health measure with a strong predictive value for subsequent morbidity and mortality [55]. Research findings around the world echo [56,57] that equitable access to quality care is critical to reducing racial inequity.

Several limitations need to be noted regarding the present study. The first limitation is the SIH/DATASUS database only includes public hospital admissions. It does not include hospital admissions under the private health system, which serves approximately 30% of Brazil's population. The second limitation is the database is an administrative dataset and thus does not look at unique patients. Therefore, patients admitted to the hospital several times are counted as individual patients and may present in the SIH/DATASUS database multiple times. Due to the severity of ALD, repeated admissions are likely, which could impact numbers. To mitigate these duplications, we performed data deduplication by generating a unique key. The third limitation is that since our study is a cross-sectional study, we cannot determine causal relationships. The fourth limitation is that our analysis lacked access to certain patient-related, sociodemographic, and socioeconomic variables due to database limitations. ALD diagnosis was identified using ICD-10 codes, which is subject to possible inaccuracy. Furthermore, it's important to note that ALD is often underdiagnosed and undertreated [58], which may lead to an underestimation of the true prevalence of this condition. Fifth, the database lacks information on alcohol use disorder and metabolic parameters necessary for assessing metabolic dysfunction-associated ALD, limiting our ability to provide a comprehensive picture of the dual pathology often seen in these patients. Lastly, SIH/DATASUS's ethnicity registration is user-dependent and subject to interpretation errors. The racial ambiguity inherent in Brazil due to its history of interlacing ethnicities makes this particularly problematic, especially distinguishing between the Black and Pardo categories [59]. The subjective nature of race classification can lead to disparities.

5ConclusionsIn conclusion, this study illustrates that COVID-19 disproportionately impacted patients in racial and ethnic minority groups. The trend of black and pardo ALD-related hospitalizations significantly increased after the pandemic; in contrast, the other population group was not significantly impacted. This study aligns with existing literature suggesting the pandemic has widened health-related racial inequities. In addition, this study underscores the need to address social determinants of health to mitigate the disproportionate burden that public health crises have on minorities.