Driver stress is a phenomenon many have studied in probably all five continents. It has been the focus of curiosity for all sorts of disciplines, and science has been unable to curb it, much less park it.

ObjectivesThis study aims to generate a unique scale that can be used in Spanish speaking countries regardless of culture or geography.

Method and MaterialsA sample of 1954 drivers from Mexico, Guatemala, Costa Rica, Chile and Spain was comprised. Through this study, the original 21 items of the ISET (Stressful Situations in Transit Inventory, in Spanish) were used to carry out both an Exploratory Factorial Analysis as well as a Confirmatory Factorial Analysis.

ResultsAs a result, a 9 item scale was created that is valid for use in Spanish countries.

ConclusionsAlthough further research is warranted, the LatinSET is now valid for its use in Spanish-speaking countries.

El estrés en conductores es un fenómeno que muchos han estudiado en probablemente los cinco continentes del mundo. Ha sido el enfoque de estudio de una gran variedad de disciplinas, pero la ciencia no ha podido desgranarlo, ni mucho menos eliminarlo por completo.

ObjetivosEste estudio tiene como objetivo generar una nueva escala que pueda ser usada en países de habla hispana sin importar la cultura o la geografía.

Material y métodosUna muestra de 1,954 conductores de México, Guatemala, Costa Rica, Chile y España fue recolectada. A través de este estudio, el juego original de 21 ítems del ISET (Inventario de Situaciones Estresantes en el Tránsito) fueron utilizados para llevar a cabo análisis factorial exploratorio y confirmatorio.

ResultadosComo resultado, una escala de 9 ítems fue creada que es válida para su uso en países hispanoparlantes.

ConclusionesA pesar de que se requiere de más estudios relevantes, el LatinSET está listo para ser usado.

Selye (1978) described stress as a phenomenon in human well-being more than 40 years ago. Lazarus and Folkman (1984) made a vital breakthrough in the study of stress and its impact on psychological and cognitive mechanisms related to how a human being copes with the strain he or she is subjected to. Since then, it's study has permeated fields of study and fields of application, such as self-esteem and humor (Stieger, Formann, & Burger, 2011), hormones (Zilioli & Watson, 2012), neurotransmitters (Jonassaint et al., 2012), war (Eggerman & Panter-Brick, 2010), sports performance (Calleja & Lorenzo, 2008), education (Twenge & Zhang, 2004), and of course, traffic psychology (Dorantes-Argandar, Cerda-Macedo, Tortosa-Gil, & Ferrero Berlanga, 2015; Dorantes-Argandar, Rivera-Vázquez, & Cárdenas-Espinoza, 2019; Dorantes Argandar, Tortosa Gil, & Ferrero Berlanga, 2016).

The definition of urban context has seen several difficulties during its conception, probably because there are several issues in consensus around the particularities that are inherent to every situation, every city, and every country (Dorantes-Argandar, Rivera-Vázquez, et al., 2019). Some characteristics have been described in several studies (Durán Romero, 2000; Ho, Wong, & Chang, 2015; Kelly et al., 2010; Lima-Aranzaes, Juárez-García, & Arias-Galicia, 2012; Routledge, 2016): such as crowds, size of population, infrastructure involved in means of transportation, activities other than agriculture carried out by the population, exposition to violent acts, environmental pollution, stress vulnerability, crime, traffic and vulnerable neighborhoods.

Studies on the matter of urban contexts have been carried out in other cities, regarding stress or stress related topics, such as risk (Cats, Yap, & van Oort, 2016), crowding (Haywood, Koning, & Monchambert, 2017), psychology of use (Fu & Juan, 2017; Jaśkiewicz & Besta, 2014), commodity (Imre & Çelebi, 2017), accidents (La, Duong, Lee, & Meuleners, 2017), aberrant driving (Mallia, Lazuras, Violani, & Lucidi, 2015), and preferences regarding the interior of buses (Waerden, Couwenberg, & Wets, 2018). Stress has also been studied in diverse urban settings, such as urban drivers (Dorantes-Argandar & Ferrero-Berlanga, 2016; Dorantes-Argandar, Tortosa-Gil, & Ferrero-Berlanga, 2016), urban violence victims (Rocha-Rego et al., 2012), health and illness (Segerstrom & O’Connor, 2012), parenting skills (Ajilchi, Borjali, & Janbozorgi, 2011), cocaine use (Ross et al., 2013), video-game playing (Hébert, Béland, Dionne-Fournelle, Crête, & Lupien, 2005), post-traumatic stress disorder (Aleksandra, Martinovic, Vuckovic, & Dickov, 2010; Polusny et al., 2008), car accidents (Dorantes-Argandar, Cerda-Macedo, Tortosa-Gil, & Ferrero-Berlanga, 2015), and aggressive driving (Wickens, Mann, Stoduto, Ialomiteanu, & Smart, 2011), amongst many others.

Stress in the field of traffic psychology has seen a surge in studies over the last ten years, including driver aggression (Herrero-Fernández, 2011; Li, Yao, Jiang, & Li, 2014; Sârbescu, Stanojević, & Jovanović, 2014; Stephens, Hill, & Sullman, 2016; Wickens et al., 2011), pressure and time (Cœugnet, Naveteur, Antoine, & Anceaux, 2013), and risky driving (Beck & Watters, 2016; Emo, Matthews, & Funke, 2016; Sarma, Carey, Kervick, & Bimpeh, 2013; Ulleberg, 2001), personality (Beck, Wang, & Mitchell, 2006; Ge et al., 2014; Taubman – Ben-Ari, Kaplan, Lotan, & Prato, 2016) amongst others. However, little work has been done in how these phenomena behave in Spanish-speaking countries, much less the development of useful instruments to evaluate them. This is why the main goal of this study was to create an instrument that is valid for use in Spanish-speaking countries, and that this instrument should evaluate stress in drivers. This study provides information relevant to content validity of the instrument here presented, although it is based in a study that had the same goal, but only provided content validity for a single city in Mexico. Said content validity is acquired for 5 Spanish-speaking countries, which allows further studies to be carried out to make up for the limitations this study has.

MethodProcedureThe main researcher sought colleagues, fellows and friends to collaborate in the project here stated. A team of 10 researchers collected data through an online platform in all five countries, and a pen and pencil format was used when quotas were not met. The data recollection period lasted about six months. This paper attempts to provide construct validity (Cohen & Swerdlik, 2009; Hair, Anderson, Tatham, Black, & Cano, 1999) for the instrument here presented. Analyses were carried out on the SPSS v. 19 and the AMOS module for the same software v. 20.

ParticipantsA total sample of 1954 drivers was comprised, throughout five different Spanish-speaking countries: Mexico (28.5%), Costa Rica (25.6%), Guatemala (25.4%), Chile (10.2%), and Spain (10.2%). Fifty two point five percent of participants were male, and the most frequent occupations were: student (19.6%), psychologist (5.8%), employee (5.1%), engineer (4.8%), salesperson (3.6%), teacher (3.4%), lawyer (2.5%), and manager (2.4%). Seventeen point eight percent of participants manifested having been in a car accident in the last 12 months, 59.5% in all of their lives. Age mean was 35.44 (SD=11.63), mean for years of schooling was 15.08 (SD=3.06), and mean for daily hours of driving was 2.62 (SD=1.77).

InstrumentsThe instrument used for this study was the Stressful Situations in Traffic Inventory (its name in Spanish is ISET) which has been used in several studies that were carried out in Mexico (Dorantes-Argandar, Cerda-Macedo, & Ferrero-Berlanga, 2019; Dorantes-Argandar, Cerda-Macedo, Tortosa-Gil, Ferrero-Berlanga, & Ferrero Berlanga, 2015; Dorantes-Argandar, Cerda-Macedo, Tortosa-Gil, & Ferrero Berlanga, 2015; Dorantes-Argandar and Ferrero-Berlanga, 2016; Dorantes-Argandar et al., 2016; Sedano-Jiménez & Dorantes-Argandar, 2018), however, these studies are restricted to only a few cities in the same country. All 21 items used in (Dorantes-Argandar et al., 2016) were used in this study for purpose of the LatinSET's validation, here presented. Internal consistency in these studies has scored an α=.80 or higher. It evaluates stress in a 5 point Likert scale, being 1 not stressful and 5 very stressful.

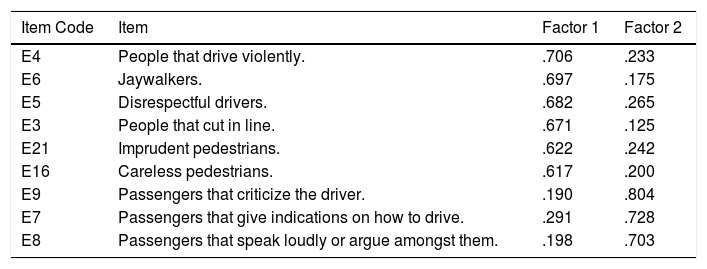

ResultsThe sample was divided in half using the SPSS random assigning feature. Half was used for the exploratory factor analysis, and the other half for the confirmatory factor analysis. Cronbach's alphas are presented for each factor analysis, and both samples are not statistically different. The EFA was attempted on the 21 original items of the ISET using the maximum likelihood extraction method, which yielded a 2 factor scale that includes 9 items. Factor loadings are displayed in Table 1. This half of the sample had a mean of 3.27 and a standard deviation of .79. The items here presented are translated from Spanish and are stated in the questionnaire as is.

Factor loadings for the EFA of the LatinSET.

| Item Code | Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| E4 | People that drive violently. | .706 | .233 |

| E6 | Jaywalkers. | .697 | .175 |

| E5 | Disrespectful drivers. | .682 | .265 |

| E3 | People that cut in line. | .671 | .125 |

| E21 | Imprudent pedestrians. | .622 | .242 |

| E16 | Careless pedestrians. | .617 | .200 |

| E9 | Passengers that criticize the driver. | .190 | .804 |

| E7 | Passengers that give indications on how to drive. | .291 | .728 |

| E8 | Passengers that speak loudly or argue amongst them. | .198 | .703 |

Table 1 displays the factor loadings for the two factor structure found in the ISET. All items have communalities above .5 and the scale explains 62.94% of total variance. Varimax rotation was applied, and the scale passed the Goodness-of-fit Test (X2=320.75 d.f.=19 p≤.001). All items correlate significantly with each other, and the scale scored a Cronbach's α of .86, which is an excellent level of internal consistency (Vera-Jiménez, Ávila-Guerrero, & Dorantes-Argandar, 2014). This structure was then tested on the AMOS for the Confirmatory Factorial Analysis.

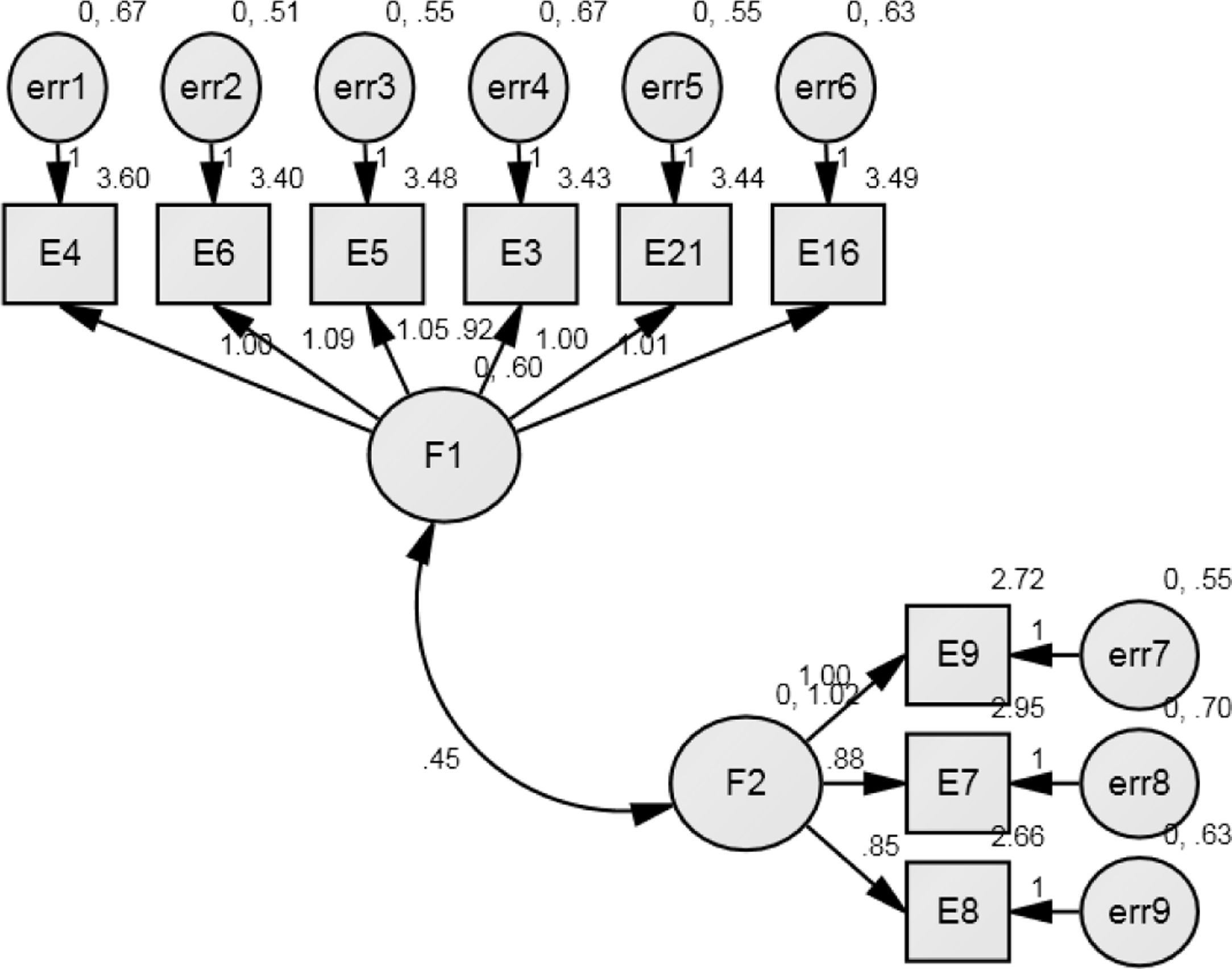

The CFA was then calculated on the other half of the sample, which is depicted in Fig. 1. This half of the sample had a mean of 3.24 and a standard deviation of .79.

This factorial structure achieved minimum requirements of fit (X2=430.04 d.f.=26 p≤.001), but did not meet requirements for excellent levels of adjustment (CFI=.88 TLI=.8 RMSEA=.13) (Escobedo-Portillo, Hernández-Gómez, Estebané-Ortega, & Martínez-Moreno, 2016; Ruiz, Pardo, & Martín, 2010). Internal consistency acquired excellent levels through an α that scored .86 (Vera-Jiménez et al., 2014). The LatinSET has a good level of fit and is valid for use in at least these five Spanish-speaking countries, although higher levels of fit were expected.

DiscussionThe instrument here provided had good indicators of construct validity, and is now ready for further studies in Spanish speaking countries. The methodology here presented furthers the work presented in Dorantes Argandar, Tortosa Gil, and Ferrero Berlanga (2016). This paper holds content validity (Cohen & Swerdlik, 2009) for the LatinSET with good measures of fit (Escobedo-Portillo et al., 2016; Ruiz et al., 2010; Vaz-Leal et al., 2014), and very good internal consistency (Vera-Jiménez et al., 2014). The study of stress in traffic psychology in Spanish-speaking countries now holds a powerful tool for further studies that aim to understand the relationship stress has in well-being and other psychological phenomena, or other phenomena in general, for that matter. Selye (1978) himself stated that urban settings, people gatherings and traffic have an impact on an individual's relationship with its environment, and Lazarus and Folkman (1984) agreed later. Since then, many have flocked to lay bricks on the road to understanding stress (Campos, Iraurgui, Páez, & Velasco, 2004; Casado, 2002; Emo et al., 2016; Hennessy & Wiesenthal, 1999; Herzberg, 2009; Qu, Zhang, Zhao, Zhang, & Ge, 2016). Urban concentrations have made transportation not only a complex system; it also subjects individuals to situations which place drivers in extreme difficulties while operating a moving vehicle, which may cause him or her bodily harm, to the extent that the mere exposure to said risks is a cause of loss of the well-being an individual possessed prior to being exposed. The accurate measurement of this loss is a corner stone in developing policy that faces these factors head on. Urbanization was supposed to help develop communities, yet it has had a negative effect on people's lives (Muggah, 2012). Although there are previous instruments that evaluate stress (Cœugnet et al., 2013; Dorantes-Argandar et al., 2016; Emo et al., 2016), there are not many that focus on drivers, or instruments that are valid for use in Spanish-speaking countries.

Future studies should focus on further validation in other Spanish-speaking countries that were not included in this study, larger samples, and a better equilibrium of samples. This study's main limitation is that it did not include all Spanish-speaking countries. It cannot be said that the LatinSET is valid for its use in all of Latinamerica, much less a collection of countries or a specific country. However, the work here presented allows other researchers to generate other studies to include other countries and/or replicate the results here presented. Further studies should aim to provide convergent validity, test re-test, and more statistical information required for an instrument that should be able to evaluate stress in drivers in a more precise manner.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.