Secondary students’ low achievement and engagement in mathematics is known to relate closely to their math anxiety. Despite the international body of research, the theoretical conceptualization of the construct math anxiety is still debated, showing strong discrepancies regarding its factor structure. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to develop and validate a new instrument, called Scale for Assessing Math Anxiety in Secondary education (SAMAS), by testing several models through confirmatory factor analysis. Data were collected from 563 secondary students, with an average age of 13.96 (SD=1.09) years. Several models for the construct were tested through confirmatory factor analysis. The results largely confirmed that the hierarquical structure showed the best fit to the data (χ2(166, N=563)=361.22; RMSEA=.046; SRMR=.045; NNFI=.94; CFI=.95), resulting in the psychometrically sound 20-item SAMAS, wherein math anxiety comprises three underlying factors.

El bajo rendimiento y dedicación de los estudiantes de secundaria a las matemáticas está estrechamente relacionado con la ansiedad matemática. A pesar de la investigación internacional, la conceptualización teórica del constructo ansiedad matemática es todavía debatida, mostrando fuertes discrepancias relativas a su estructura factorial. Por tanto, el objetivo de este estudio es desarrollar y validar un nuevo instrumento, denominado Scale for Assessing Math Anxiety in Secondary Education (SAMAS), para el que se analizan diferentes modelos mediante Análisis Factorial Confirmatorio. La muestra estuvo compuesta por 563 estudiantes, con una edad media de 13.96 (DE=1.09) años. Los resultados ampliamente confirmaron que la estructura jerárquica fue la que arrojó el mejor ajuste del modelo (χ2[166, N=563]=361.22; RMSEA=.046; SRMR=.045; NNFI=.94; CFI=.95), resultando en un instrumento psicométricamente robusto de 20 items, compuesto por 3 factores subyacentes.

In recent years, math anxiety has received increasing interest because of its adverse effects on the learning and mastery of Mathematics from an early age. It is defined as feelings of tension or worries that hinder the successful completion of tasks involving manipulation of numbers and mathematical reasoning not only in school settings, but also in a wide range of daily life situations (Richardson & Suinn, 1972).

Although it has been shown to exist across all age ranges, there is growing evidence that math anxiety has its roots in upper elementary school and increases in severity from 5th through 12th grade, reaching peak levels in 14- to 16-year-old students (e.g., Legg & Locker, 2009; Scarpello, 2007). In attempts to summarize these correlational studies, Hembree (1990) and Ma (1999) conducted one meta-analysis each. The results underscored estimated correlation values of −.27 to −.34 for the previously mentioned age group (that is, secondary students).

Its detrimental impact during this period leads to a math-related avoidance pattern in adulthood, which manifests in a wide range of behavioral symptoms such as trying not to use mathematical reasoning whenever it is possible. This troubling pattern, in turn, results in an adverse effect on individuals’ career choices and long-term professional success (e.g., Ashcraft & Krause, 2007; Krinzinger, Kaufmann, & Willmes, 2009), as well as poorer mathematical skills and a continuous struggle to perform simple numerical tasks, namely addition or subtraction (Ashcraft & Ridley, 2005).

In addition, when analyzing its origin, several authors have found that math anxiety is a specific type of anxiety related to, but distinct from, both general anxiety trait and test anxiety (Wu, Willcutt, Escovar, & Menon, 2013). These findings highlight the non-intellectual nature of math anxiety, a hypothesis which was originally proposed in theoretical terms (Ashcraft & Krause, 2007; Beilock & Carr, 2005; Beilock, Gunderson, Ramirez, & Levine, 2010), but has been recently proven in the field of neurocognitive research (Young, Wu, & Menon, 2012).

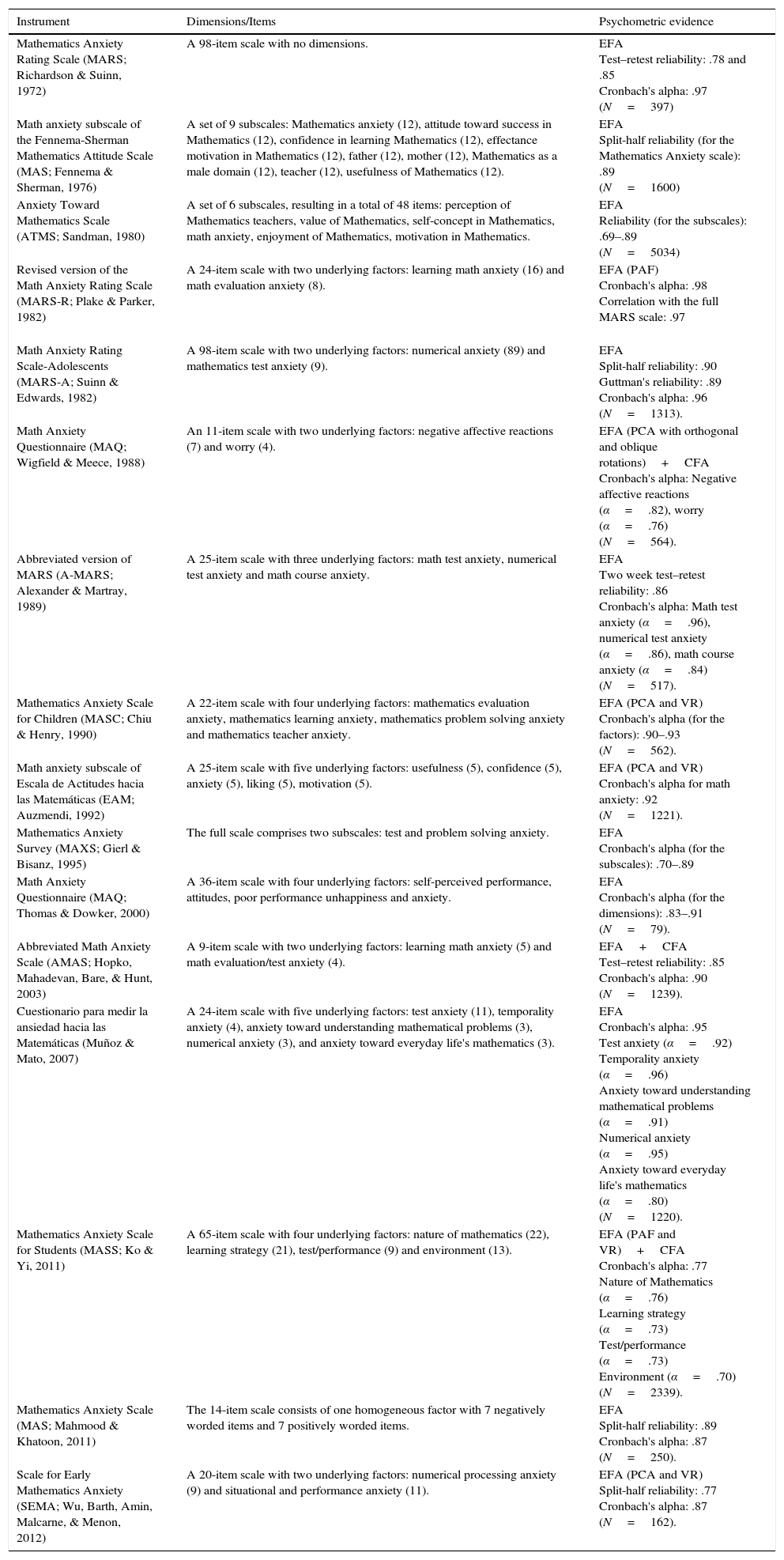

Despite its relevance, knowledge about the theoretical conceptualization of math anxiety is still inconclusive. A literature review of the existing measures for assessing math anxiety (see Table 1) drawn from peer reviewed articles yielded no agreement in the dimensionality of the construct.

Instruments for assessing math anxiety.

| Instrument | Dimensions/Items | Psychometric evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematics Anxiety Rating Scale (MARS; Richardson & Suinn, 1972) | A 98-item scale with no dimensions. | EFA Test–retest reliability: .78 and .85 Cronbach's alpha: .97 (N=397) |

| Math anxiety subscale of the Fennema-Sherman Mathematics Attitude Scale (MAS; Fennema & Sherman, 1976) | A set of 9 subscales: Mathematics anxiety (12), attitude toward success in Mathematics (12), confidence in learning Mathematics (12), effectance motivation in Mathematics (12), father (12), mother (12), Mathematics as a male domain (12), teacher (12), usefulness of Mathematics (12). | EFA Split-half reliability (for the Mathematics Anxiety scale): .89 (N=1600) |

| Anxiety Toward Mathematics Scale (ATMS; Sandman, 1980) | A set of 6 subscales, resulting in a total of 48 items: perception of Mathematics teachers, value of Mathematics, self-concept in Mathematics, math anxiety, enjoyment of Mathematics, motivation in Mathematics. | EFA Reliability (for the subscales): .69–.89 (N=5034) |

| Revised version of the Math Anxiety Rating Scale (MARS-R; Plake & Parker, 1982) | A 24-item scale with two underlying factors: learning math anxiety (16) and math evaluation anxiety (8). | EFA (PAF) Cronbach's alpha: .98 Correlation with the full MARS scale: .97 |

| Math Anxiety Rating Scale-Adolescents (MARS-A; Suinn & Edwards, 1982) | A 98-item scale with two underlying factors: numerical anxiety (89) and mathematics test anxiety (9). | EFA Split-half reliability: .90 Guttman's reliability: .89 Cronbach's alpha: .96 (N=1313). |

| Math Anxiety Questionnaire (MAQ; Wigfield & Meece, 1988) | An 11-item scale with two underlying factors: negative affective reactions (7) and worry (4). | EFA (PCA with orthogonal and oblique rotations)+CFA Cronbach's alpha: Negative affective reactions (α=.82), worry (α=.76) (N=564). |

| Abbreviated version of MARS (A-MARS; Alexander & Martray, 1989) | A 25-item scale with three underlying factors: math test anxiety, numerical test anxiety and math course anxiety. | EFA Two week test–retest reliability: .86 Cronbach's alpha: Math test anxiety (α=.96), numerical test anxiety (α=.86), math course anxiety (α=.84) (N=517). |

| Mathematics Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; Chiu & Henry, 1990) | A 22-item scale with four underlying factors: mathematics evaluation anxiety, mathematics learning anxiety, mathematics problem solving anxiety and mathematics teacher anxiety. | EFA (PCA and VR) Cronbach's alpha (for the factors): .90–.93 (N=562). |

| Math anxiety subscale of Escala de Actitudes hacia las Matemáticas (EAM; Auzmendi, 1992) | A 25-item scale with five underlying factors: usefulness (5), confidence (5), anxiety (5), liking (5), motivation (5). | EFA (PCA and VR) Cronbach's alpha for math anxiety: .92 (N=1221). |

| Mathematics Anxiety Survey (MAXS; Gierl & Bisanz, 1995) | The full scale comprises two subscales: test and problem solving anxiety. | EFA Cronbach's alpha (for the subscales): .70–.89 |

| Math Anxiety Questionnaire (MAQ; Thomas & Dowker, 2000) | A 36-item scale with four underlying factors: self-perceived performance, attitudes, poor performance unhappiness and anxiety. | EFA Cronbach's alpha (for the dimensions): .83–.91 (N=79). |

| Abbreviated Math Anxiety Scale (AMAS; Hopko, Mahadevan, Bare, & Hunt, 2003) | A 9-item scale with two underlying factors: learning math anxiety (5) and math evaluation/test anxiety (4). | EFA+CFA Test–retest reliability: .85 Cronbach's alpha: .90 (N=1239). |

| Cuestionario para medir la ansiedad hacia las Matemáticas (Muñoz & Mato, 2007) | A 24-item scale with five underlying factors: test anxiety (11), temporality anxiety (4), anxiety toward understanding mathematical problems (3), numerical anxiety (3), and anxiety toward everyday life's mathematics (3). | EFA Cronbach's alpha: .95 Test anxiety (α=.92) Temporality anxiety (α=.96) Anxiety toward understanding mathematical problems (α=.91) Numerical anxiety (α=.95) Anxiety toward everyday life's mathematics (α=.80) (N=1220). |

| Mathematics Anxiety Scale for Students (MASS; Ko & Yi, 2011) | A 65-item scale with four underlying factors: nature of mathematics (22), learning strategy (21), test/performance (9) and environment (13). | EFA (PAF and VR)+CFA Cronbach's alpha: .77 Nature of Mathematics (α=.76) Learning strategy (α=.73) Test/performance (α=.73) Environment (α=.70) (N=2339). |

| Mathematics Anxiety Scale (MAS; Mahmood & Khatoon, 2011) | The 14-item scale consists of one homogeneous factor with 7 negatively worded items and 7 positively worded items. | EFA Split-half reliability: .89 Cronbach's alpha: .87 (N=250). |

| Scale for Early Mathematics Anxiety (SEMA; Wu, Barth, Amin, Malcarne, & Menon, 2012) | A 20-item scale with two underlying factors: numerical processing anxiety (9) and situational and performance anxiety (11). | EFA (PCA and VR) Split-half reliability: .77 Cronbach's alpha: .87 (N=162). |

Note. PCA=Principal Component Analysis, VR=Varimax Rotation, PAF=Principal Axis Factoring.

When reviewing the studies summarized in Table 1, it could be concluded that: (a) researchers do not agree on the factor structure for math anxiety; (b) some instruments targeted at measuring math anxiety also include some factors related to other constructs (e.g., attitudes toward math); (c) the great majority of existing instruments have been psychometrically supported by exploratory factor analyses, with still a scarcity of confirmatory consistency; and (d) there is a general lack of peer-reviewed tools for assessing math anxiety among secondary students in Spanish-speaking contexts.

Therefore, based on previous literature and theoretical considerations, in the present research math anxiety is defined based on Hopko's (2003) classification and previous studies on the construct, whereby two factors are proposed as critical elements: anxiety about the process of learning mathematics and anxiety toward math evaluation. Aiming at completing its factor structure, a third factor is proposed as relevant in explaining the construct: anxiety toward everyday life's math-related tasks, which is in line with the widely acknowledged definition by Richardson and Suinn (1972). Accordingly, math anxiety is conceptualized to have three latent factors:

Everyday life's math anxiety encompasses a broad range of affective responses to students’ everyday situations that require mathematical reasoning. For example, a student may feel nervous about having to do a mental calculation to estimate the total price of a purchase.

Math learning anxiety includes affective responses that a math student may experience during different situations of the math learning process that take place in the scholar setting. For example, the feeling of worry when having to solve a math problem.

Math test anxiety refers to feelings a math student may experience when either preparing or doing a math test. This dimension is considered different, although related to, the previous one. In fact, it is conceivable that a student enjoys the subject of Mathematics but feels nervous about doing a math test.

Consequently, based on the limitations drawn from the literature review on existing instruments and the theoretical conceptualization exposed above, the main goal of the present study was to develop and validate, by means of confirmatory analyses, the Scale for Assessing Math Anxiety in Secondary education (SAMAS), wherein math anxiety comprises three underlying factors: everyday life's math anxiety, math learning anxiety and math test anxiety.

MethodParticipantsA random sample from six schools was extracted, and the cluster sampling method was then applied. That is, within those selected schools, all secondary student groups from second and fourth grades were considered eligible for the study.

With this procedure, the research sample consisted of 563 secondary students (39.3% females, 60.7% males) from 36 different classes from the province of Biscay (Basque Country Autonomous Region, Spain). The average age of the participants was 13.96 (SD=1.09) years, ranging from 12 to 16. As regards the educational level, 47.42% were enrolled in second grade and 52.58% in fourth grade.

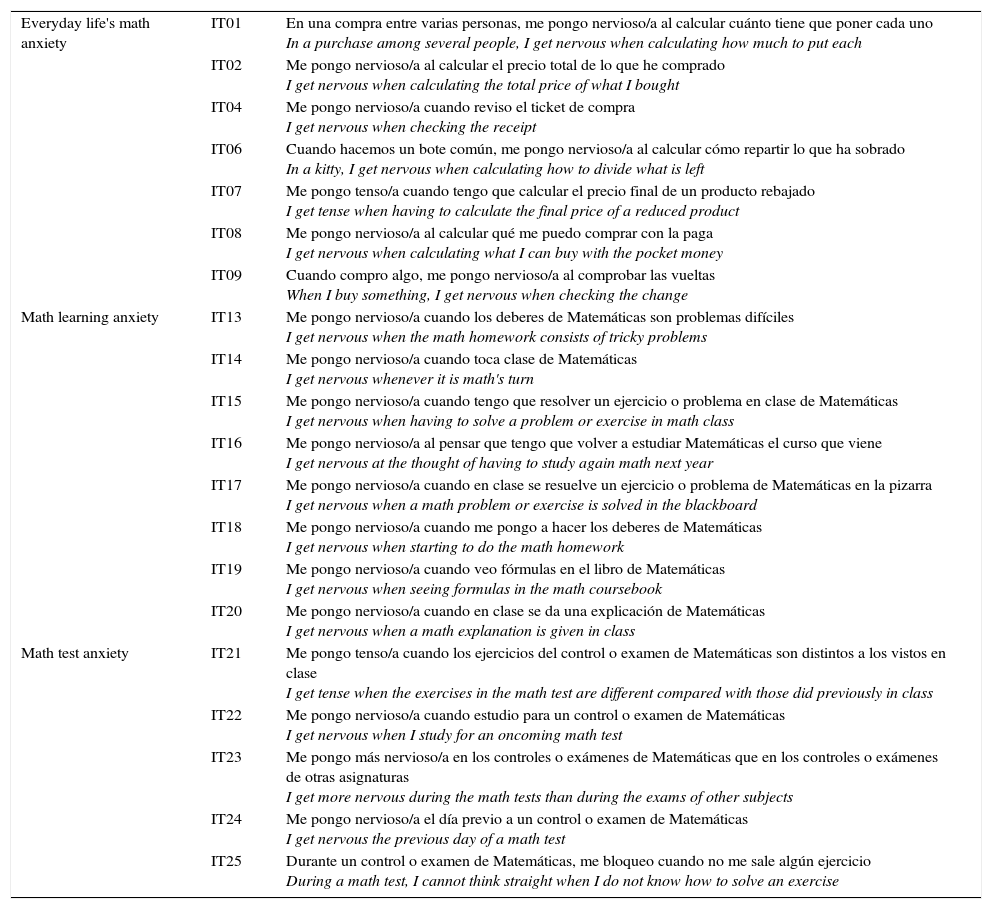

InstrumentsScale for Assessing Math Anxiety in Secondary education (SAMAS). It comprised three underlying factors: everyday life's math anxiety (e.g., “Me pongo nervioso/a al calcular el precio total de lo que he comprado” [I get nervous when calculating the total price of what I bought]), math learning anxiety (e.g., “Me pongo nervioso/a cuando toca clase de matemáticas” [I get nervous whenever it is math's turn]) and math test anxiety (e.g., “Me pongo más nervioso/a en los controles o exámenes de matemáticas que en los controles o exámenes de otras asignaturas” [I get more nervous during the math tests than during the exams of other subjects]). The final version consisted of 20 items (see Appendix 1) on a continuous response scale ranging from 0 (Strongly disagree) to 10 (Strongly agree). Its development, as well as psychometric properties, is detailed in the present study.

Math performance. It was assessed by students’ score on a math curriculum-based test, entirely based on the widely validated diagnostic tests (Gobierno Vasco, 2010) and PISA assessment (Gobierno Vasco, 2011). The former includes basic mathematical contents across the first cycle of Compulsory Secondary Education; whereas the latter does across the second cycle. The time limit to complete the test is 40min in both cases.

For their correction, the guidelines given by their authors are applied, obtaining a single cumulative score, based on the sum of correct answers, which was then transformed to a standard score ranging from 0 to 10.

A sociodemographic questionnaire gathered participants’ personal background information: age, sex and secondary grade in which they are enrolled.

ProcedureOnce the research project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Deusto, the principals from the selected schools were contacted via email and informed of the nature of the research. They, in turn, presented it for approval at a staff meeting. After written permission was granted by the schools, a cover letter was sent to students’ parents or guardians to inform them of the purpose of the study and explain that collected data were going to be dealt with confidentiality and used solely for research purposes. In addition, prior to participation, students were also informed of the general purpose of the study and of their rights as participants, stressing that their participation was anonymous and voluntary. No incentives (e.g., academic credits) were offered in exchange for participation.

Data were collected by the first author and a purpose-trained assistant and the instruments were administered collectively in the students’ usual classrooms in the absence of the teacher, taking 55min to complete. Either the author or the trained assistant was in the classroom the entire time to explain the procedure. No student withdrew from participation during the instruments administration.

Data analysisAfter obtaining the initial pool of items for the new instrument, a review panel of nine experts on research and didactics was established to provide evidence about content validity. They were asked to classify each item within just one dimension, and then rate its accuracy and clarity of writing on a scale ranging from 0 to 10. They were also prompted to send comments or suggestions for improvement if considered necessary. Results were analyzed according to the criteria of mean (high if M≥7.50; acceptable if 2.50≤M<7.50; low if M<2.50) and standard deviation (good if SD≤1.00; acceptable if 1.00<SD≤1.50; low if SD>1.50) for both relevance and clarity of writing, and response frequency (necessary, f≥.78, meaning that at least 7 out of 9 experts classify the item within the theoretical dimension). In addition, the Content Validity Index (CVI) was estimated for each item, setting a value of .78 as the minimum desirable cut-off for this coefficient (Lynn, 1986).

Then, prior to the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), no outliers were identified and all cases were retained for subsequent analysis. The univariate normality obtained for all variables, the low missing values rate (<5%) estimated in dataset and the large sample size used in the study validated the implementation of Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation. Due to the multivariate non-normality of data, the parameters of the CFA were estimated using Satorra–Bentler robust corrections. Items were forced to load on their hypothesized factors. The variances for the first observed indicator of each latent variable were fixed to 1, and the variances for all error weights and the remaining parameters were freely estimated (Ullman, 2006).

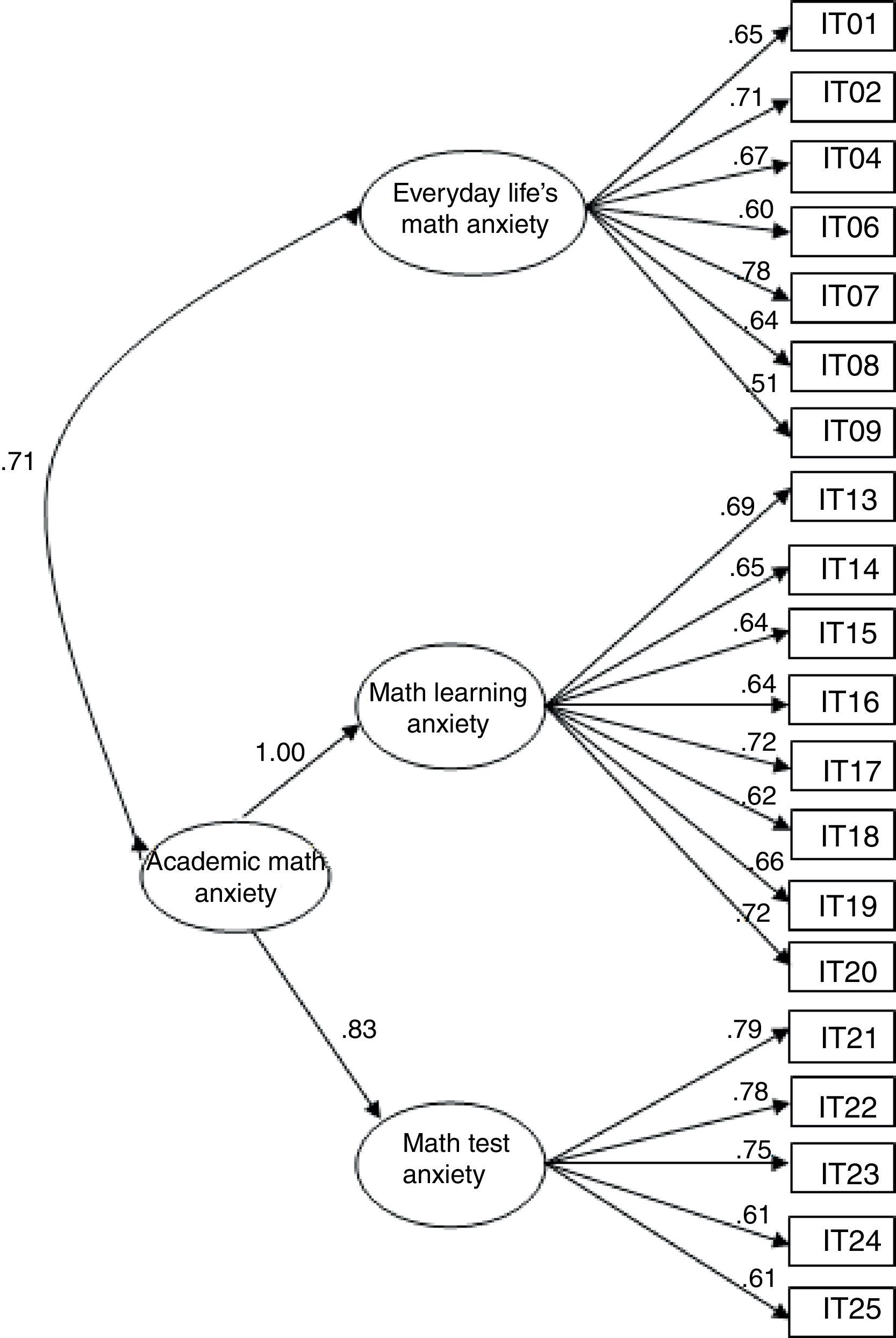

Three a priori models for assessing math anxiety were subjected to CFA: firstly, a unidimensional model in which all items were indicators of a single math anxiety factor; secondly, a three-factor model in which the items were assumed to measure three factors (namely, everyday life's math anxiety, math learning anxiety and math test anxiety); thirdly, a hierarchical model comprising a first order factor (everyday life's math anxiety) and a second-order factor (on which both math learning anxiety and math test anxiety loaded on a second-order factor referring to academic math anxiety).

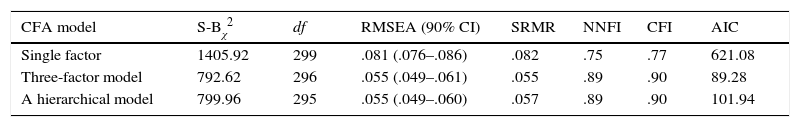

Several fit indices and desirable cut-offs were used to judge the adequacy of the CFA (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2010): a) the S-Bχ2/df statistics should be lower than 3.0; b) the Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA), with the relative 90% confidence interval, should be lower than .08 (good) or .06 (excellent); c) the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) should be lower than .08; d) the Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI) should be greater than .90 (good) or .95 (excellent); and e) the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) should be greater than .90 (good) or .95 (excellent). In addition, the Akaike's information criterion (AIC) was used to compare the factor structures with different estimated parameters in such a way that lower values indicated higher parsimony for the model.

Discriminant validity was examined through the inter-factor correlations, and internal consistency was assessed with the Composite Reliability (CR) and Cronbach's coefficient (α). To interpret the scores, values above .50 for the former were considered adequate (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) and values above .70 for the latter were considered acceptable (Nunnally, 1978).

Finally, convergent validity was assessed with the Pearson correlation coefficients between math anxiety and other construct referred in literature (i.e., math performance). According to Cohen's (1988) criteria, values of r around .10 are considered to be small correlations, r around .30, moderate; and r around .50, high.

ResultsInitial pool of items and evidence of content validityThe development process for the new instrument SAMAS began by specifying both the construct math anxiety and its underlying factors. As previously noted, in the present study three latent factors are taken as the basis for its subsequent conceptualization: everyday life's math anxiety, math learning anxiety and math test anxiety.

Thus, as recommended by AERA, APA, and NCME (2008), existing instruments were firstly considered for the development of a preliminary pool of items. As it was necessary to translate the great majority of existing instruments to Spanish, the guidelines by Muñiz, Elosua, and Hambleton (2013) were followed. Redundant items were removed and newly written items were developed for the proposed dimensions. As a consequence, a total of 32 items were obtained and sorted as follows: everyday life's math anxiety (13), math learning anxiety (13) and math test anxiety (6).

As part of the content validity process, results from the review panel indicated that overall, items were positively evaluated in terms of accuracy and clarity of writing and were categorized into just one dimension. On over the half of all statements (62.5%) the CVI obtained the maximum score, and on one-fifth, approximately, of all statements (18.5%), the CVI ranged from the threshold of .78 to 1. Only six items did not meet the cut-off. These were discarded and the remaining 26 items, which comprised the first version of SAMAS, were distributed as follows: everyday life's math anxiety (11), math learning anxiety (9) and math test anxiety (6).

Confirmatory factor analysis: evidence of construct and discriminant validityTable 2 shows the goodness-of-fit indices of the three CFA models for assessing math anxiety. The single factor model did not reach adequate values with both RMSEA and SRMR above .06, and both NNFI and CFI below .95. The three-factor model showed an overall adequate fit-to-data. With the exception of NNFI, the remaining indices met the cut-offs. However, the three factors were strongly correlated (r=.53–.85). Specifically, the strong correlation between math learning anxiety and math test anxiety (r=.85) suggested potential model redundancy and casted doubts on the discriminant validity between these two factors. The hierarchical structure, which attempts to model the strong correlations among the three first-order factors by loading math learning anxiety and math test anxiety on a second-order factor called academic math anxiety, was a significantly better fit-to-data, compared to the unidimensional model (ΔS-Bχ2=605.96, Δdf=4, p<.001). Therefore, the second-order factor model emerged as the preferred structure.

Goodness-of-fit indices for the three alternative models.

| CFA model | S-Bχ2 | df | RMSEA (90% CI) | SRMR | NNFI | CFI | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single factor | 1405.92 | 299 | .081 (.076–.086) | .082 | .75 | .77 | 621.08 |

| Three-factor model | 792.62 | 296 | .055 (.049–.061) | .055 | .89 | .90 | 89.28 |

| A hierarchical model | 799.96 | 295 | .055 (.049–.060) | .057 | .89 | .90 | 101.94 |

Note. S-Bχ2=Satorra–Bentler Chi-square, df=degrees of freedom, RMSEA=Root Mean Square Error of Aproximation, SRMR=Standardized Root Mean Square Residual, NNFI=Non-Normed Fit Index, CFI=Comparative Fit Index, AIC=Akaike's information criterion.

To enact modifications representing an improvement on the final fit, the hierarchical model was further inspected through the standardized residual covariance scores, the standardized factor loadings and the conceptual relevance of the items. Based on these considerations, six items were discarded. The re-specified model (see Fig. 1) yielded good values for the goodness-of-fit indices (S-Bχ2(166, N=563)=361.22, p<.001; RMSEA (90% IC)=.046 (.039–.053); SRMR=.045; NNFI=.94; CFI=.95).

All standardized factor loadings were statistically significant and all three first-order factors strongly loaded on the second-order factor (p<.05). Specifically, the standardized factor loadings for the everyday life's math anxiety ranged from .51 to .78; from .62 to .72 for math learning anxiety factor; and from .61 to .79 for math test anxiety factor. Additional properties of the final 20-item SAMAS were assessed with the Composite Reliability (CR) and Cronbach's alpha (α) of each factor. The reliability analyses showed good internal consistency for everyday life's math anxiety (CR=.79, α=.83), math learning anxiety (CR=.83, α=.86) and math test anxiety (CR=.78, α=.84) factors.

Evidence of convergent validityModerate negative correlations were found between math learning anxiety and math performance (r=−.38, p<.01) and between math test anxiety and math performance (r=−.37, p<.01); whereas a low correlation was found between everyday life's math anxiety and math performance (r=−.16, p<.01).

DiscussionResearch on math anxiety is undoubtedly contingent on the psychometric properties of the measures for assessing the construct. In this context, a review on the existing instruments warrants cautious considerations about the lack of agreement on the factor structure for math anxiety. Therefore, the main goal of this study is to develop and validate a new measure, called Scale for Assessing Math Anxiety in Secondary education (SAMAS), which attempts to furnish insights into the factor structure of math anxiety by suggesting three factors drawn from an integrative literature review: everyday life's math anxiety, math learning anxiety and math test anxiety.

Confirmatory analyses show that the best and most parsimonious structure is a hierarchical model, consisting of a two-order factor and a first-order factor. The former refers to academic math anxiety, and comprises both math test anxiety and math learning anxiety; whereas the latter refers to everyday life's math anxiety. Such structure for assessing math anxiety, although aligned with the widely acknowledged definition given by Richardson and Suinn (1972), has been first proposed in literature, contrary to two-factor (Hopko, Mahadevan, Bare, & Hunt, 2003; Wigfield & Meece, 1988) or four-factor (Ko & Yi, 2011) models tested through confirmatory approaches in previous research.

Regarding convergent evidence, negative moderate correlations were found between math learning anxiety and math performance, as well as between math test anxiety and math performance. Interestingly, the correlation between everyday life's math anxiety and math performance was smaller, which makes sense as it is the only factor referring to feelings of tension evoked in math-related situations outside the school setting. These results were in line with previous studies (e.g., Ho et al., 2000; Suinn & Edwards, 1982). To this respect, it is important to highlight the results of the meta-analyses conducted by Hembree (1990) and Ma (1999), who estimated correlations from −.27 to −.34 between math anxiety and math performance among secondary students. As a result, the Pearson's correlations obtained were appropriate compared to the results from previous studies considering the same constructs.

Despite the promising findings, there are also some limitations. First, data were collected using a cluster-sampling method, which means that the results are not entirely generalizable. Although the participating schools were previously selected via a simple random method and the resulting sample group was representative for the research purposes, larger samples from different sociodemographic contexts are needed to further assess the invariance of the factor structure. Second, this study provides evidence of good psychometric properties of the instrument but, likewise, it would be interesting to provide further evidence of validity by assessing the temporal stability.

Additionally, SAMAS has been initially developed for its use with secondary education participants. It would be highly interesting, therefore, to adapt and validate the scale with other populations such as, for example, primary education or college students. Indeed, since math anxiety experiences a deep change in the transition from upper elementary school to junior high school, investigating this turning point with psychometrically sound instruments would be of great relevance.

In conclusion, based on the reported results, the developed 20-item SAMAS can be used by educators or researchers as a little time demanding and psychometrically sound instrument for measuring and monitoring secondary education students’ levels of math anxiety in Spanish-speaking settings. Its use would allow detecting potential at-risk students and consequently, design and implement, as early as possible, strategies or methodologies aiming at alleviating detected levels of math anxiety, in general, or of a specific dimension, in particular. Indeed, the inclusion of a component encompassing feelings of tension in non-scholastic settings is considered to be a contribution in the present research, since to date only one instrument considered a similar component when defining the construct (Muñoz & Mato, 2007). However, not only the number of items in that scale appeared to be inadequate to yield strong psychometric properties, but also the validation process relied completely on exploratory techniques without any confirmatory consistency. Therefore, the hierarchical model largely confirmed in the present study emerges as a more comprehensive structure for explaining and measuring math anxiety, both in academic and non-academic settings.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

This research was funded by the University of Deusto Research Training Grants Programme 2013–2016 (University of Deusto, Bilbao).

Final version of the SAMAS.

| Everyday life's math anxiety | IT01 | En una compra entre varias personas, me pongo nervioso/a al calcular cuánto tiene que poner cada uno In a purchase among several people, I get nervous when calculating how much to put each |

| IT02 | Me pongo nervioso/a al calcular el precio total de lo que he comprado I get nervous when calculating the total price of what I bought | |

| IT04 | Me pongo nervioso/a cuando reviso el ticket de compra I get nervous when checking the receipt | |

| IT06 | Cuando hacemos un bote común, me pongo nervioso/a al calcular cómo repartir lo que ha sobrado In a kitty, I get nervous when calculating how to divide what is left | |

| IT07 | Me pongo tenso/a cuando tengo que calcular el precio final de un producto rebajado I get tense when having to calculate the final price of a reduced product | |

| IT08 | Me pongo nervioso/a al calcular qué me puedo comprar con la paga I get nervous when calculating what I can buy with the pocket money | |

| IT09 | Cuando compro algo, me pongo nervioso/a al comprobar las vueltas When I buy something, I get nervous when checking the change | |

| Math learning anxiety | IT13 | Me pongo nervioso/a cuando los deberes de Matemáticas son problemas difíciles I get nervous when the math homework consists of tricky problems |

| IT14 | Me pongo nervioso/a cuando toca clase de Matemáticas I get nervous whenever it is math's turn | |

| IT15 | Me pongo nervioso/a cuando tengo que resolver un ejercicio o problema en clase de Matemáticas I get nervous when having to solve a problem or exercise in math class | |

| IT16 | Me pongo nervioso/a al pensar que tengo que volver a estudiar Matemáticas el curso que viene I get nervous at the thought of having to study again math next year | |

| IT17 | Me pongo nervioso/a cuando en clase se resuelve un ejercicio o problema de Matemáticas en la pizarra I get nervous when a math problem or exercise is solved in the blackboard | |

| IT18 | Me pongo nervioso/a cuando me pongo a hacer los deberes de Matemáticas I get nervous when starting to do the math homework | |

| IT19 | Me pongo nervioso/a cuando veo fórmulas en el libro de Matemáticas I get nervous when seeing formulas in the math coursebook | |

| IT20 | Me pongo nervioso/a cuando en clase se da una explicación de Matemáticas I get nervous when a math explanation is given in class | |

| Math test anxiety | IT21 | Me pongo tenso/a cuando los ejercicios del control o examen de Matemáticas son distintos a los vistos en clase I get tense when the exercises in the math test are different compared with those did previously in class |

| IT22 | Me pongo nervioso/a cuando estudio para un control o examen de Matemáticas I get nervous when I study for an oncoming math test | |

| IT23 | Me pongo más nervioso/a en los controles o exámenes de Matemáticas que en los controles o exámenes de otras asignaturas I get more nervous during the math tests than during the exams of other subjects | |

| IT24 | Me pongo nervioso/a el día previo a un control o examen de Matemáticas I get nervous the previous day of a math test | |

| IT25 | Durante un control o examen de Matemáticas, me bloqueo cuando no me sale algún ejercicio During a math test, I cannot think straight when I do not know how to solve an exercise |