To evaluate the use of β-blockers and to monitor heart rate in Mexican patients with coronary artery disease.

MethodsCLARIFY is an outpatients registry with stable CAD. A total of 33,283 patients from 45 countries were enrolled between November 2009 and July 2010 from which 1342 were Mexican patients.

ResultsThe mean HR pulse was 70bpm (beats per minute). Patients in Mexico were compared with the remaining global CLARIFY population. Patients in Mexico had a higher incidence of acute myocardial infarction and percutaneous coronary intervention, and lower incidence of revascularization surgery compared with the remaining CLARIFY population. More often, Mexican patients presented with diabetes, but less often hypertension and stroke. These patients were split into three mutually exclusive groups of HR ≤60 (N=263), HR 61–69 (N=356) and HR ≥70 (N=722). Patients with elevated HR had a higher incidence of diabetes and higher diastolic blood pressure on average than those with controlled HR. Regarding the use of β-blockers, they were used in 63.3% of patients, 2.7% showed intolerance or contraindication to treatment to monitor heart rate, and ivabradine was used in 2.3%. Out of approximately 849 patients receiving treatment of β-blockers, 52.1% had ≥70bpm HR.

ConclusionsIn a large proportion of Mexican patients with stable coronary disease the HR remain elevated, >70bpm, even with the use of β-blockers; this requires further attention.

Evaluar en pacientes con enfermedad coronaria estable, el uso de beta-bloqueadores y la frecuencia cardiaca.

MétodosEl estudio CLARIFY es un registro internacional de pacientes ambulatorios con enfermedad coronaria estable. Se incluyeron un total de 33,283 pacientes de 45 países durante el periodo de noviembre de 2009 a julio de 2010; de estos, 1342 pacientes fueron mexicanos.

ResultadosLa frecuencia cardiaca (FC) media fue de 70 lpm (latidos por minuto). Se compararon los pacientes mexicanos con la población internacional incluida en el estudio. Los primeros tuvieron una mayor incidencia de infarto agudo del miocardio e intervención coronaria percutánea y menor incidencia de cirugía de revascularización comparado con la población mundial. La población Mexicana presentó mayor incidencia de diabetes pero menor incidencia de hipertensión y EVC. A estos se les dividio en tres grupos mutuamente excluyentes FC ≤60 (N=263), FC 61-69 (N=356) y FC ≥70 (N=722). Los pacientes con FC elevada presentaron mayor incidencia de diabetes, y un registro mayor de tensión arterial sistólica comparado con aquellos con FC controlada. Respecto al uso de beta bloqueadores estos se administraron a 63.3% de los pacientes; el 2.7% mostró intolerancia o contraindicación al tratamiento con estos fármacos. Se administró ivabradina al 2.3% de los pacientes. De los 849 pacientes que recibieron tratamiento con beta-bloqueadores, el 52.1% mostró FC de ≥ 70 lpm.

ConclusionesLa gran mayoría de los pacientes mexicanos con enfermedad coronaria estable la FC permaneció elevada, >70bpm, aun con el uso de beta bloqueadores.

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the worldwide leading cause of death,1,2 yet there is a paucity of data regarding the clinical characteristics and management of outpatients with stable CAD. Most of the available data come from patients admitted for acute coronary syndromes or treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). In addition, data often come from Europe or North America. The prospeCtive observational LongitudinAl RegIstry oF patients with stable coronary arterY disease (CLARIFY) registry was initiated to improve our knowledge regarding patients with stable CAD from a broader geographic perspective.3 The main objectives of the registry are to define contemporary stable CAD outpatients in terms of their demographic characteristics, clinical profiles, management, and outcomes; identify gaps between evidence-based recommendations and treatment; and investigate long-term prognostic determinants in this population.

Heart rate (HR) is a primary determinant of myocardial ischemia, and has been established as a prognostic factor in patients with CAD4–8 and in those with congestive heart failure (CHF).9 It has also been correlated with the risk of future coronary events.4,10 The elevation of the HR in healthy patients usually indicates a modification between sympathetic and parasympathetic system because of the raise of the sympathetic tone or decrease of the parasympathetic tone.11 β-Blockers have many other actions, such as reducing the HR. Current data show that HR reduction with pure bradycardic agents is also associated with clinical benefits, such as prevention of angina and reduction of myocardic ischemia.12–14 Little is known about the actual HR obtained in clinical practice, even in patients receiving HR-lowering treatments such as β-blockers. Similarly, there is a paucity of data in the management of patients with elevated HR in CAD related with the use of β-blockers and other HR-lowering agents.

The analysis describes the use of a large contemporary database stemming from a broad geographic representation; Mexican patients were compared to other global patients, specifically for the stable Mexican outpatients with CAD, the HR achieved, the use of β-blockers, and described the determinants of elevated HR in the Mexican population.

MethodsCLARIFY is an ongoing international, prospective, observational, longitudinal cohort study in stable CAD outpatients, with 5 years of follow-up. Patients eligible for enrollment were outpatients with stable CAD proven by a history of at least one of the following: documented myocardial infarction (>3 months ago); coronary stenosis >50% in coronary angiography; chest pain with myocardial ischemia proven by stress electrocardiogram and stress echocardiography, or myocardial imaging; and history of coronary artery bypass graft surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention (performed >3 months ago).

Patients hospitalized for cardiovascular disease within the previous 3 months (including for revascularization), patients for whom revascularization was planned, and patients with conditions expected to hamper participation or 5-year follow-up (e.g. limited cooperation or legal capacity, serious non-cardiovascular disease, conditions limiting life expectancy, or severe cardiovascular disease [such as advanced heart failure, severe valve disease, history of valve repair/replacement, etc.]) were excluded from participating in the study. Information collected at baseline included: (a) demographics; (b) risk factors and lifestyle; (c) medical history and current symptoms; (d) physical examination: heart rate determined by pulse palpation; (e) interpretation of last electrocardiogram taken within the previous 6 months; (f) lab report: fasting blood glucose, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), cholesterol, triglycerides, serum creatinine, and hemoglobin, if available; (g) current chronic medical treatments taken by the patient for more than 7 days prior to the entry in the registry. Data are collected and analyzed at an independent academic statistics center at the Robertson Centre for Biostatistics, University of Glasgow, UK. The study is being performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the National Research Ethics Service, Isle of Wight, Portsmouth and Southeast Hampshire Research Ethics Committee, UK. Approval was also obtained from all 45 participating countries, in accordance with local regulations before recruitment of the first participant. All patients signed a written informed consent to participate, in accordance with national and local guidelines. The CLARIFY Registry was evaluated by the ethics committee and registered in the ISRCTN registry of clinical trials with the number ISRCTN43070564.

Data are summarized using number (percentage) for categorical variables and mean (standard deviation) or median [lower quartile, upper quartile] for the continuous variables, depending on the distribution of the data. Comparisons between the Mexican population and the rest of the CLARIFY population were tested using Pearson's chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for the categorical variables, and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal–Wallis test for the continuous variables. Depending on the distribution of the data, these methods were also used to compare differences between heart rate groups of ≤60bpm, 61–69bpm and ≥70bpm, within the Mexican population.

The cut-off of 70bpm to determine an elevated HR for the multivariable model was selected based on the results of several studies showing that it is an important prognostic threshold across a variety of patient populations.4,12,15–17 All clinical baseline variables were considered for entry into the model as predictors of HR ≥70bpm and univariate models for each were produced. The use of HR-lowering medications was considered to be the most important treatment variable, and so this was the only treatment predictor included in the analyses. The multivariable model was then built using a stepwise selection method applied to the remaining significant univariate predictors, with the use of HR-lowering medications being forced into the model.

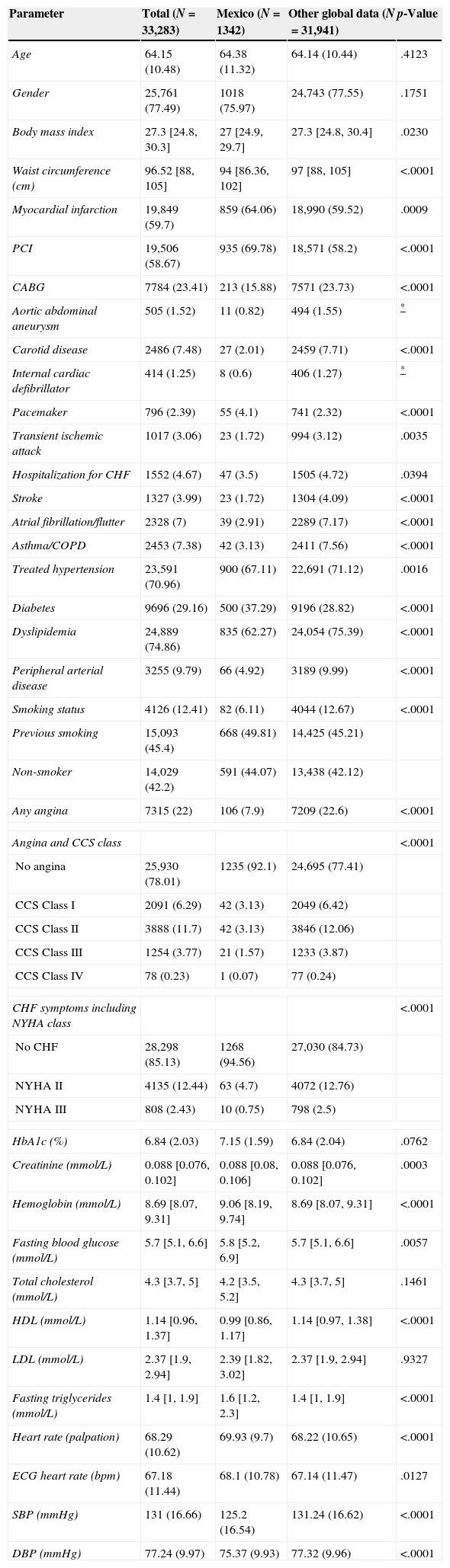

ResultsWe included a total of 33,283 patients worldwide, Mexico recruited 1342 patients; however, the heart rate was the only one recorded in 1341 patients. The standard deviation (SD) of HR of total CLARIFY patients was 10.62; Mexican patients have a SD of 9.70. The information collected is summarized in Table 1. The average age was 64 years, 76.0% were men. The median body mass index was 27; the median recorded for abdominal circumference was 94cm. Significant differences were observed in the laboral status of patients worldwide compared to Mexico, finding a 26.9% of patients withdrawn in Mexico, corresponding to 56.3% of the registered in the rest of the world. We documented 6.1% of active smokers at the time of inclusion, 49.8% with a history of smoking at some point in their lives and 44.1% never smoked. The mean systolic blood pressure was 125mmHg, while the diastolic was 75mmHg.

Demographic data characteristics of the study population classified according to Mexico vs. rest of global data.

| Parameter | Total (N=33,283) | Mexico (N=1342) | Other global data (N=31,941) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 64.15 (10.48) | 64.38 (11.32) | 64.14 (10.44) | .4123 |

| Gender | 25,761 (77.49) | 1018 (75.97) | 24,743 (77.55) | .1751 |

| Body mass index | 27.3 [24.8, 30.3] | 27 [24.9, 29.7] | 27.3 [24.8, 30.4] | .0230 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 96.52 [88, 105] | 94 [86.36, 102] | 97 [88, 105] | <.0001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 19,849 (59.7) | 859 (64.06) | 18,990 (59.52) | .0009 |

| PCI | 19,506 (58.67) | 935 (69.78) | 18,571 (58.2) | <.0001 |

| CABG | 7784 (23.41) | 213 (15.88) | 7571 (23.73) | <.0001 |

| Aortic abdominal aneurysm | 505 (1.52) | 11 (0.82) | 494 (1.55) | * |

| Carotid disease | 2486 (7.48) | 27 (2.01) | 2459 (7.71) | <.0001 |

| Internal cardiac defibrillator | 414 (1.25) | 8 (0.6) | 406 (1.27) | * |

| Pacemaker | 796 (2.39) | 55 (4.1) | 741 (2.32) | <.0001 |

| Transient ischemic attack | 1017 (3.06) | 23 (1.72) | 994 (3.12) | .0035 |

| Hospitalization for CHF | 1552 (4.67) | 47 (3.5) | 1505 (4.72) | .0394 |

| Stroke | 1327 (3.99) | 23 (1.72) | 1304 (4.09) | <.0001 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 2328 (7) | 39 (2.91) | 2289 (7.17) | <.0001 |

| Asthma/COPD | 2453 (7.38) | 42 (3.13) | 2411 (7.56) | <.0001 |

| Treated hypertension | 23,591 (70.96) | 900 (67.11) | 22,691 (71.12) | .0016 |

| Diabetes | 9696 (29.16) | 500 (37.29) | 9196 (28.82) | <.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 24,889 (74.86) | 835 (62.27) | 24,054 (75.39) | <.0001 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 3255 (9.79) | 66 (4.92) | 3189 (9.99) | <.0001 |

| Smoking status | 4126 (12.41) | 82 (6.11) | 4044 (12.67) | <.0001 |

| Previous smoking | 15,093 (45.4) | 668 (49.81) | 14,425 (45.21) | |

| Non-smoker | 14,029 (42.2) | 591 (44.07) | 13,438 (42.12) | |

| Any angina | 7315 (22) | 106 (7.9) | 7209 (22.6) | <.0001 |

| Angina and CCS class | <.0001 | |||

| No angina | 25,930 (78.01) | 1235 (92.1) | 24,695 (77.41) | |

| CCS Class I | 2091 (6.29) | 42 (3.13) | 2049 (6.42) | |

| CCS Class II | 3888 (11.7) | 42 (3.13) | 3846 (12.06) | |

| CCS Class III | 1254 (3.77) | 21 (1.57) | 1233 (3.87) | |

| CCS Class IV | 78 (0.23) | 1 (0.07) | 77 (0.24) | |

| CHF symptoms including NYHA class | <.0001 | |||

| No CHF | 28,298 (85.13) | 1268 (94.56) | 27,030 (84.73) | |

| NYHA II | 4135 (12.44) | 63 (4.7) | 4072 (12.76) | |

| NYHA III | 808 (2.43) | 10 (0.75) | 798 (2.5) | |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.84 (2.03) | 7.15 (1.59) | 6.84 (2.04) | .0762 |

| Creatinine (mmol/L) | 0.088 [0.076, 0.102] | 0.088 [0.08, 0.106] | 0.088 [0.076, 0.102] | .0003 |

| Hemoglobin (mmol/L) | 8.69 [8.07, 9.31] | 9.06 [8.19, 9.74] | 8.69 [8.07, 9.31] | <.0001 |

| Fasting blood glucose (mmol/L) | 5.7 [5.1, 6.6] | 5.8 [5.2, 6.9] | 5.7 [5.1, 6.6] | .0057 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 4.3 [3.7, 5] | 4.2 [3.5, 5.2] | 4.3 [3.7, 5] | .1461 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.14 [0.96, 1.37] | 0.99 [0.86, 1.17] | 1.14 [0.97, 1.38] | <.0001 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2.37 [1.9, 2.94] | 2.39 [1.82, 3.02] | 2.37 [1.9, 2.94] | .9327 |

| Fasting triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.4 [1, 1.9] | 1.6 [1.2, 2.3] | 1.4 [1, 1.9] | <.0001 |

| Heart rate (palpation) | 68.29 (10.62) | 69.93 (9.7) | 68.22 (10.65) | <.0001 |

| ECG heart rate (bpm) | 67.18 (11.44) | 68.1 (10.78) | 67.14 (11.47) | .0127 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 131 (16.66) | 125.2 (16.54) | 131.24 (16.62) | <.0001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 77.24 (9.97) | 75.37 (9.93) | 77.32 (9.96) | <.0001 |

Information provided is number (percentage) for categorical variables and mean (SD) or median [lower quartile, upper quartile] for the continuous variables depending on the distribution of the data.

Regarding clinical history, in Mexico there was increased incidence of diabetes mellitus type 2 (37.3%), acute myocardial infarction (64.1%) and percutaneous coronary intervention (69.8%) compared to those reported worldwide. In contrast there was a higher incidence of heart failure worldwide at 4.7% (Mexico 3.5%), CABG 23.7% (Mexico 15.9%), stroke 4.1% (Mexico 1.7%), atrial flutter/fibrillation 7.2% (Mexico 2.9%) and dyslipidemia 75.4% (Mexico 62.3%).

Referring to the presence of angina in Mexico we recorded 106 patients divided into four groups depending on the classification of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Class I documenting 42 patients, 42 in Class II, 21 in Class III and 1 in Class IV. The same methodology was used for recording heart failure symptoms according to the NYHA classification; 1268 were patients without heart failure symptoms, 63 were NYHA II, 10 were NYHA III and LVEF was also determined by finding a mean of 52.6%.

In Mexico there were 894 patients with non-invasive tests for myocardial ischemia and 229 with evidence of presence of myocardial ischemia. Angiographically we determined stenosis >50% in the left main artery in 4.9% patients, in the left anterior descending artery in 63.2% patients, in the circumflex in 30.6% patients and in the right coronary artery in 40.1% patients; 5.7% showed no significant stenosis and 14.3% did not have a record of coronary angiography.

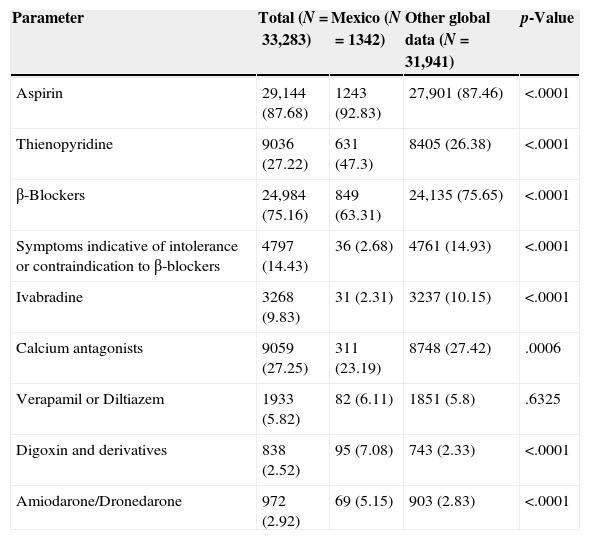

Medication use is summarized in Table 2. Antihypertensives usage in the Mexican population (1342) was reported in 65.7% of the population with ACEI/ARB, 19.2% used nitrates, and calcium antagonists were used by 23.2% of the population. Referring to antiplatelet therapy 1243 patients were taking aspirin, 631 thienopyridine and 119 different antiplatelet therapies. The use of lipid-lowering medications was found in 1176 patients. In Mexico the use of β-blockers was present in 849 patients (63.3%), symptoms of intolerance to β-blockers in 36 patients (2.7%), and ivabradine was used in 31 patients (2.3%). The worldwide records for the same data yielded the following results: use of β-blockers in 75.6%, symptoms of intolerance to β-blockers in 14.93%, and use of ivabradine in 10.1%, showing marked increase in these parameters globally compared to Mexico.

Medication data of the study population classified according to Mexico vs. rest of global data.

| Parameter | Total (N=33,283) | Mexico (N=1342) | Other global data (N=31,941) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | 29,144 (87.68) | 1243 (92.83) | 27,901 (87.46) | <.0001 |

| Thienopyridine | 9036 (27.22) | 631 (47.3) | 8405 (26.38) | <.0001 |

| β-Blockers | 24,984 (75.16) | 849 (63.31) | 24,135 (75.65) | <.0001 |

| Symptoms indicative of intolerance or contraindication to β-blockers | 4797 (14.43) | 36 (2.68) | 4761 (14.93) | <.0001 |

| Ivabradine | 3268 (9.83) | 31 (2.31) | 3237 (10.15) | <.0001 |

| Calcium antagonists | 9059 (27.25) | 311 (23.19) | 8748 (27.42) | .0006 |

| Verapamil or Diltiazem | 1933 (5.82) | 82 (6.11) | 1851 (5.8) | .6325 |

| Digoxin and derivatives | 838 (2.52) | 95 (7.08) | 743 (2.33) | <.0001 |

| Amiodarone/Dronedarone | 972 (2.92) | 69 (5.15) | 903 (2.83) | <.0001 |

Heart rate was determined by pulse palpation with a mean of 69.9bpm in the Mexican population and 68.2bpm in the rest of the CLARIFY population (p<.0001), while ECG-derived HR was 68.1bpm in the Mexican population and 67.1bpm in the rest of the CLARIFY population (p=.127). Of the Mexican patients with ECG information, 882 patients had sinus rhythm, 12 fibrillation/atrial flutter and 18 tachycardia.

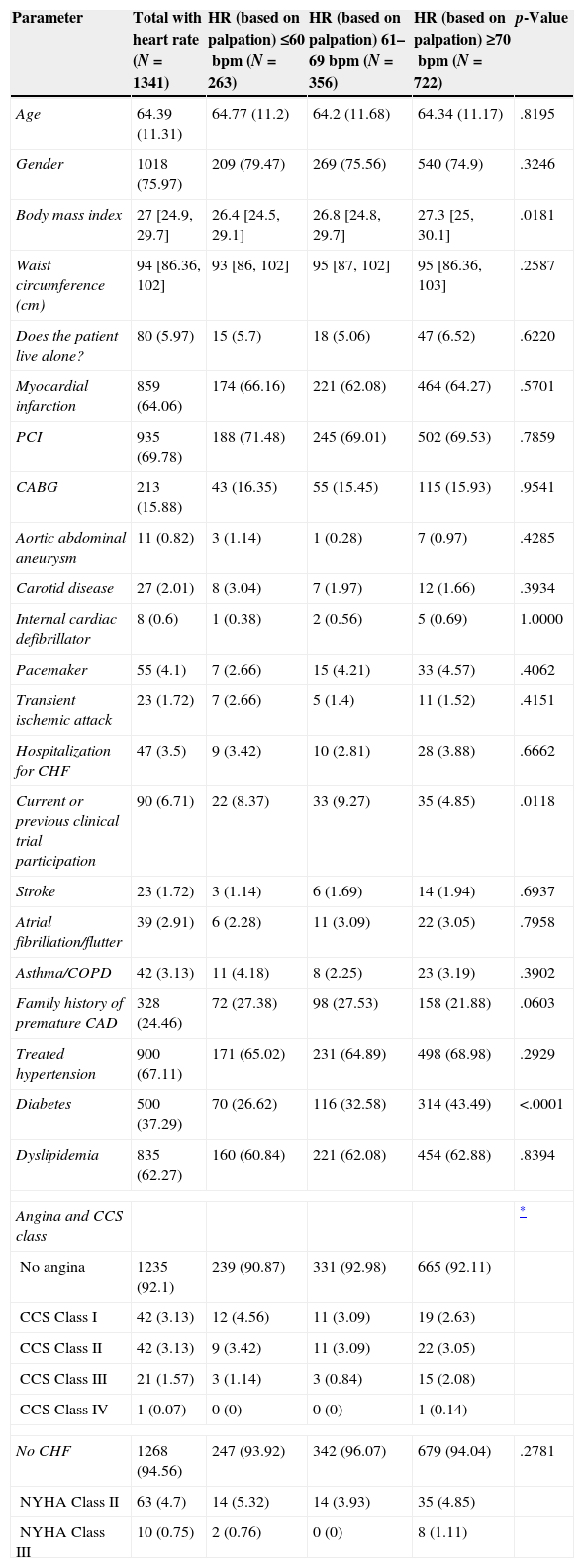

Mexican patients were split into three mutually exclusive categories using baseline pulse palpation, HR ≤60 (N=263), HR 61–69 (N=356) and HR ≥70 (N=722) (Table 3). There were some important, significant differences between the HR subgroups: patients with higher heart rates had higher BMI and more incidence of diabetes. On average, the systolic and diastolic blood pressures were also higher in the group with the highest heart rates. Regarding the use of drugs the group HR ≥70bpm had a significantly greater use of ivabradine (3.5%) compared with the HR ≤60 (1.5); higher heart rates corresponded to lower use of β-blockers (61.2% in HR ≥70 compared to 68.1% in HR ≤60), although this was not statistically significant.

Characteristics of the Mexico population classified according to resting heart rate.

| Parameter | Total with heart rate (N=1341) | HR (based on palpation) ≤60bpm (N=263) | HR (based on palpation) 61–69bpm (N=356) | HR (based on palpation) ≥70bpm (N=722) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 64.39 (11.31) | 64.77 (11.2) | 64.2 (11.68) | 64.34 (11.17) | .8195 |

| Gender | 1018 (75.97) | 209 (79.47) | 269 (75.56) | 540 (74.9) | .3246 |

| Body mass index | 27 [24.9, 29.7] | 26.4 [24.5, 29.1] | 26.8 [24.8, 29.7] | 27.3 [25, 30.1] | .0181 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 94 [86.36, 102] | 93 [86, 102] | 95 [87, 102] | 95 [86.36, 103] | .2587 |

| Does the patient live alone? | 80 (5.97) | 15 (5.7) | 18 (5.06) | 47 (6.52) | .6220 |

| Myocardial infarction | 859 (64.06) | 174 (66.16) | 221 (62.08) | 464 (64.27) | .5701 |

| PCI | 935 (69.78) | 188 (71.48) | 245 (69.01) | 502 (69.53) | .7859 |

| CABG | 213 (15.88) | 43 (16.35) | 55 (15.45) | 115 (15.93) | .9541 |

| Aortic abdominal aneurysm | 11 (0.82) | 3 (1.14) | 1 (0.28) | 7 (0.97) | .4285 |

| Carotid disease | 27 (2.01) | 8 (3.04) | 7 (1.97) | 12 (1.66) | .3934 |

| Internal cardiac defibrillator | 8 (0.6) | 1 (0.38) | 2 (0.56) | 5 (0.69) | 1.0000 |

| Pacemaker | 55 (4.1) | 7 (2.66) | 15 (4.21) | 33 (4.57) | .4062 |

| Transient ischemic attack | 23 (1.72) | 7 (2.66) | 5 (1.4) | 11 (1.52) | .4151 |

| Hospitalization for CHF | 47 (3.5) | 9 (3.42) | 10 (2.81) | 28 (3.88) | .6662 |

| Current or previous clinical trial participation | 90 (6.71) | 22 (8.37) | 33 (9.27) | 35 (4.85) | .0118 |

| Stroke | 23 (1.72) | 3 (1.14) | 6 (1.69) | 14 (1.94) | .6937 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 39 (2.91) | 6 (2.28) | 11 (3.09) | 22 (3.05) | .7958 |

| Asthma/COPD | 42 (3.13) | 11 (4.18) | 8 (2.25) | 23 (3.19) | .3902 |

| Family history of premature CAD | 328 (24.46) | 72 (27.38) | 98 (27.53) | 158 (21.88) | .0603 |

| Treated hypertension | 900 (67.11) | 171 (65.02) | 231 (64.89) | 498 (68.98) | .2929 |

| Diabetes | 500 (37.29) | 70 (26.62) | 116 (32.58) | 314 (43.49) | <.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 835 (62.27) | 160 (60.84) | 221 (62.08) | 454 (62.88) | .8394 |

| Angina and CCS class | * | ||||

| No angina | 1235 (92.1) | 239 (90.87) | 331 (92.98) | 665 (92.11) | |

| CCS Class I | 42 (3.13) | 12 (4.56) | 11 (3.09) | 19 (2.63) | |

| CCS Class II | 42 (3.13) | 9 (3.42) | 11 (3.09) | 22 (3.05) | |

| CCS Class III | 21 (1.57) | 3 (1.14) | 3 (0.84) | 15 (2.08) | |

| CCS Class IV | 1 (0.07) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.14) | |

| No CHF | 1268 (94.56) | 247 (93.92) | 342 (96.07) | 679 (94.04) | .2781 |

| NYHA Class II | 63 (4.7) | 14 (5.32) | 14 (3.93) | 35 (4.85) | |

| NYHA Class III | 10 (0.75) | 2 (0.76) | 0 (0) | 8 (1.11) | |

Information provided is number (percentage) for categorical variables and mean (SD) or median [lower quartile, upper quartile] for continuous variables depending on the distribution of the data.

The population was also divided depending on the use of β-blockers. Depending on their use in 849 patients, we analyzed the characteristics of this population; patients receiving β-blockers were significantly younger (mean 63.6 years) compared to those not taking β-blockers (mean 65.8 years), and had higher incidence of hypertension (70.3% compared to 61.6%) and any kind of angina (9.7% compared to 4.9%) (data not shown).

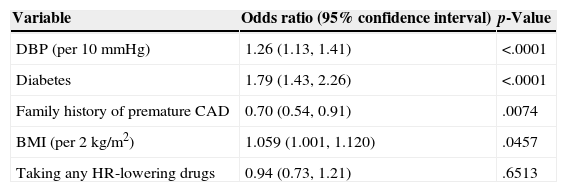

The multivariable analysis for the determinants of elevated heart rate in the Mexican population showed that patients with diabetes, increased BMI and increased diastolic blood pressure were at an increased odds of elevated heart rate, while those with a family history of premature CAD were at slightly reduced odds of increased heart rate (Table 4).

Multivariable logistic regression results for elevated heart rate using a stepwise selection model.

| Variable | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| DBP (per 10mmHg) | 1.26 (1.13, 1.41) | <.0001 |

| Diabetes | 1.79 (1.43, 2.26) | <.0001 |

| Family history of premature CAD | 0.70 (0.54, 0.91) | .0074 |

| BMI (per 2kg/m2) | 1.059 (1.001, 1.120) | .0457 |

| Taking any HR-lowering drugs | 0.94 (0.73, 1.21) | .6513 |

The analysis of the results provided a description of the Mexican population compared to the rest of the CLARIFY population. The records indicate a mean age of 64 years, with a high incidence of patients outside the international goals of BMI and waist circumference. Cigarette consumption at any time of life was present in over 50% of the study population, also the Mexican population showed a higher incidence of diabetes and myocardial infarction.

Regarding the laboral status of Mexico compared to the world, it showed that Mexico had a withdrawal rate corresponding to half of registered worldwide. We also found that the Mexican population with coronary artery disease is significantly less active compared with that recorded worldwide (data not shown).

In the Mexican population, the average heart rate was 69.9bpm, and although 63% of the population received treatment with β-blockers, only 19.6% of the population had an HR ≤60bpm, and even within the population with the use of β-blockers, 52% had HR ≥70; likewise those patients with symptoms of angina only, 22.6%, achieved HR ≤60bpm even though the guidelines for stable angina recommended HR: 55–60bpm in angina patients treated with β-blockers. By multivariable analysis, many independent predictors of HR ≥70 were found, many of which are markers of poor health status. In contrast with this results there are several publications that describe the HR with cardiovascular mortality in healthy populations. In the British Regional Heart Study18 the authors observed that in individuals without evidence of previous cardiovascular disease there was a significant association between HR and the rate of all the fatal and the non-fatal coronary events, the risk was specially elevated in individuals that has a HR >90, the raise of the risk was five times higher than the male that presented HR <60bpm. The Paris Prospective Study I19 showed in the multivariable analysis that the HR was related with sudden death and myocardial infarction. The CASTEL20 study found a higher mortality with HR >80. In the Chicago studies21 were observed that HR was a risk factor for coronary mortality, in young males and in middle aged men and women. In the French population Benetos et al.22 found that HR was a risk factor for non-cardiovascular mortality in both genders. The CASS study investigated the relationship between HR and mortality in patients with stable coronary artery disease4 and found that the total mortality, the cardiovascular mortality and cardiovascular rehospitalisation were associated with the increase in the HR. Patients with a HR baseline ≥83bpm had a total mortality and a higher cardiovascular mortality, after adjusting for multiple variables, when compared with the reference group. These epidemiological data have been reinforced by findings of clinical studies that had shown that HR reduction by drugs such as β-blockers improve prognosis in patients with acute myocardial infarction15 or heart failure,16 and it is a fundamental part of the beneficial effect of these drugs on the prognosis. In conclusion, the clinical benefits of β-blockers in patients with CAD are well established, particularly the reduction of cardiovascular events in survivors of myocardial infarction.17 The subjunctive analysis of the BEAUTIFUL study suggests that HR reduction can prevent coronary events.23,24 Although the database indicates the impact of the HR in the prognosis in CAD, and the potential benefits of lowering the HR, we found in our study an elevated heart rate, based on the multiple studies mentioned before the Mexican population had a very vulnerable cardiovascular situation. The data of Mexican mortality will be available when the CLARIFY study will be completed in 2015.

ConclusionsA large proportion of patients had an elevated heart rate, even among patients receiving β-blockers, a high percentage that handles HR ≥70, indicating a likely inaccurate dose. The study data were obtained from a random sample from a group of cardiologists, that not necessarily represent the reality of the rest of the patients seen by other physicians. Even though this study reveals that there are multiple potential barriers to more widespread use of β-blockers at appropriate doses to achieve adequate HR control, such as inadequate knowledge of evidence or treatment goals by clinicians access to care and reimbursement, comorbidities that represent contraindications or decrease tolerance to β-blockers an their side effects, and marketing efforts for other agents. Few of the patients not receiving β-blockers are intolerant to these drugs or had conditions that contraindicate its use. Therefore there is a potential for improving HR control rational use of β-blocker and other heart rate lowering medications such as ivabradine, which can be used together. Is very important to sensitize physicians about the importance of the therapeutic heart rate goal that the patients should have after a cardiovascular event. Specially if it is associated with myocardial damage and heart failure then it is necessary to insist on the use of β-blockers in optimum dose, alone or in combination with selective channel blocking drugs such as ivabradine. This drug is a suitable alternative to β-blockers for an adequate chronotropical control with the benefits of reducing cardiovascular events as has been reported in other previous studies.

FundingNo endorsement of any kind received to conduct this study/article.

Conflict of interestNone declared.