To assess the self-perception of nurses and general practitioners (GPs) toward Physical Activity on Prescription (PAP) in Madrid Primary Health-Care (PHC).

DesignA survey-cohort study.

SiteNurses and GPs of Madrid PHC System.

ParticipantsA total of 319 GPs and 285 nurses’ responders.

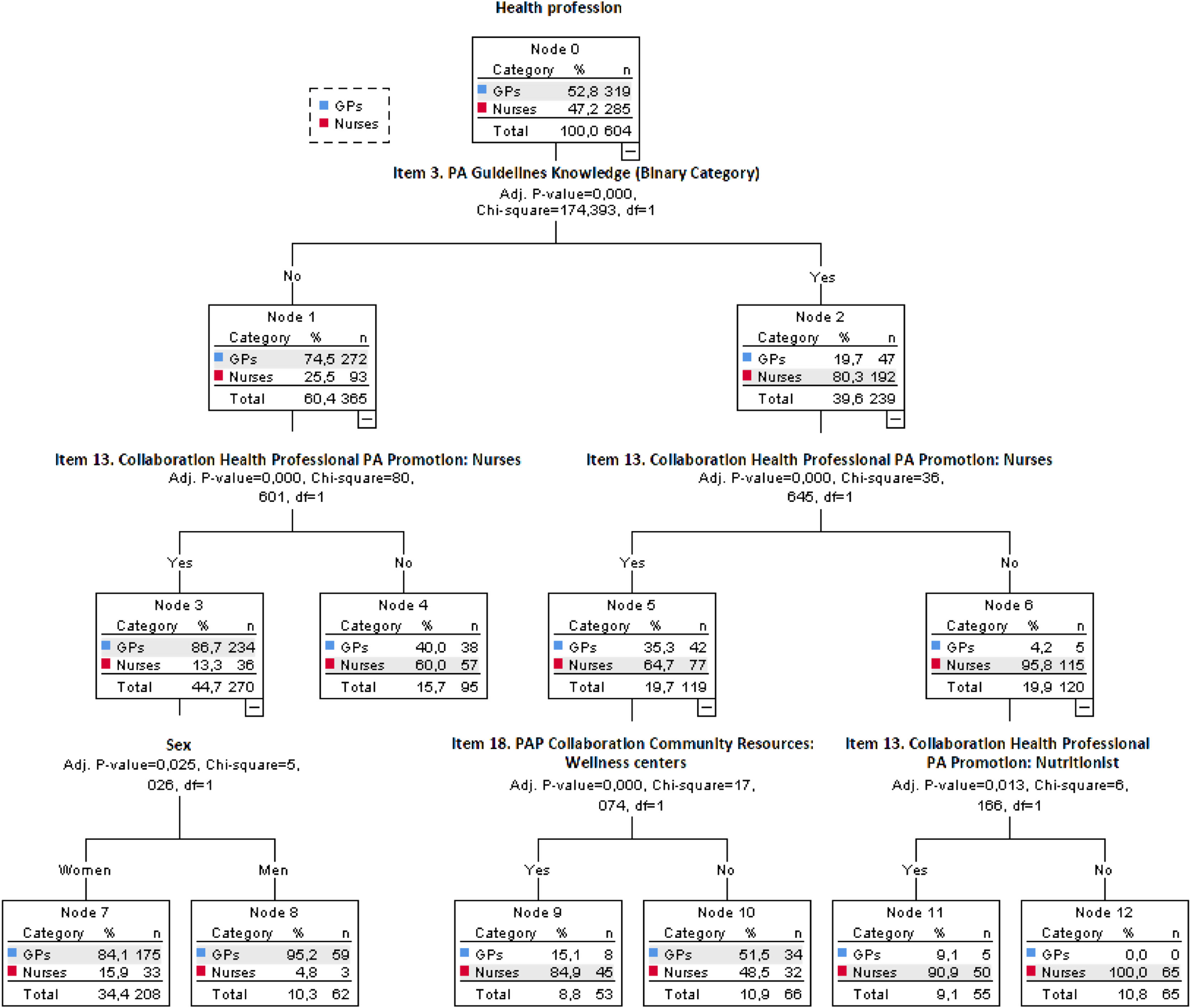

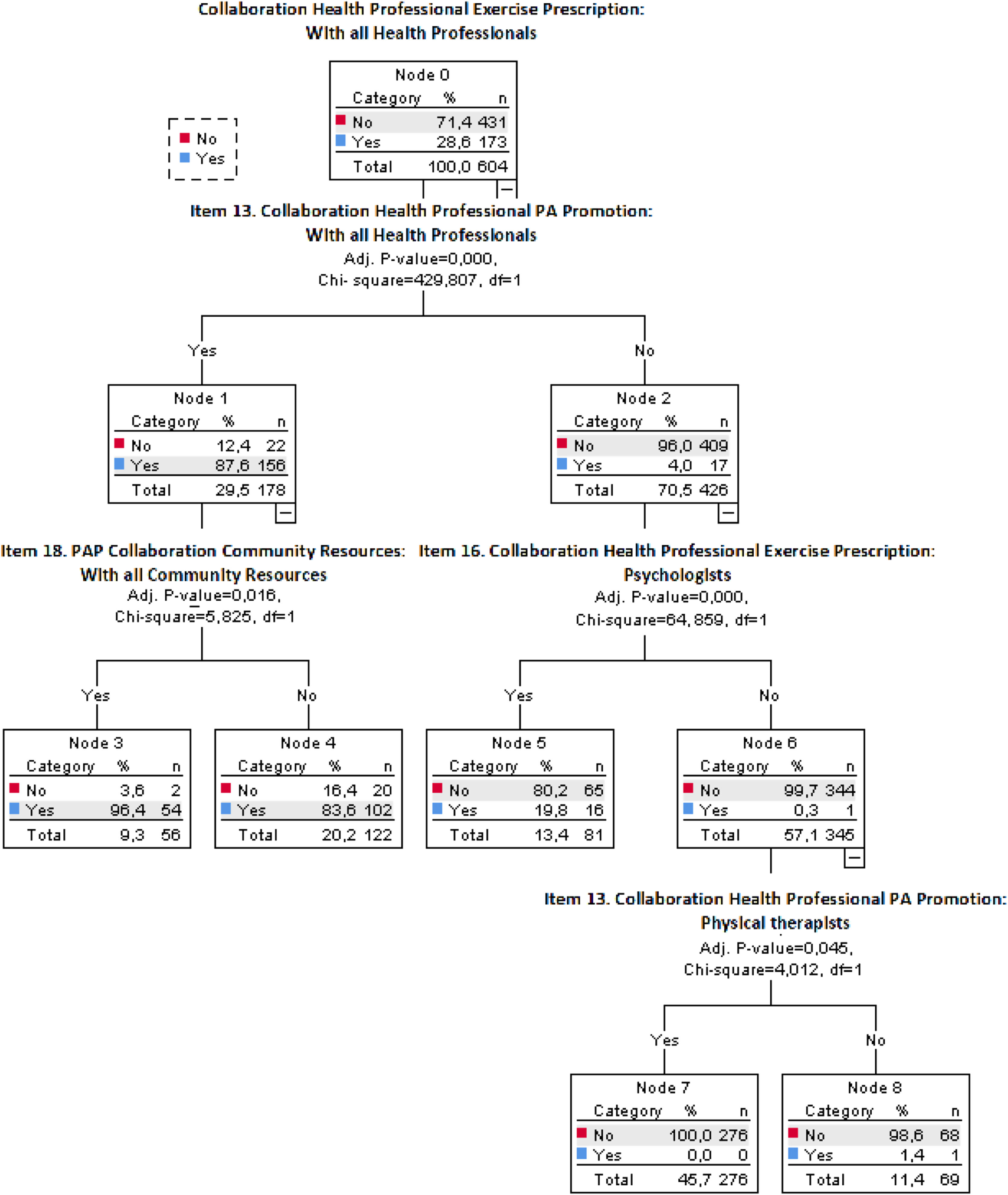

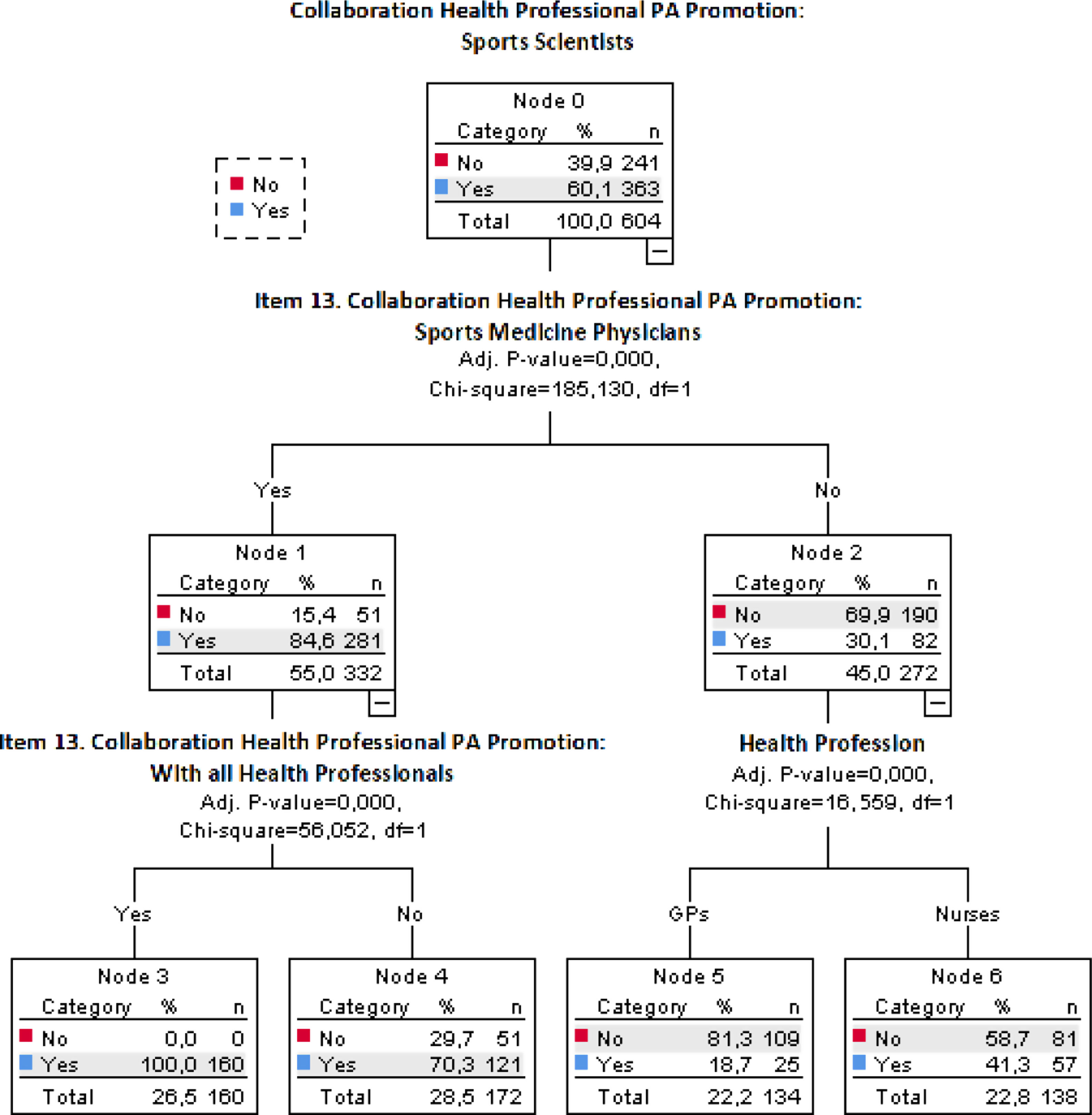

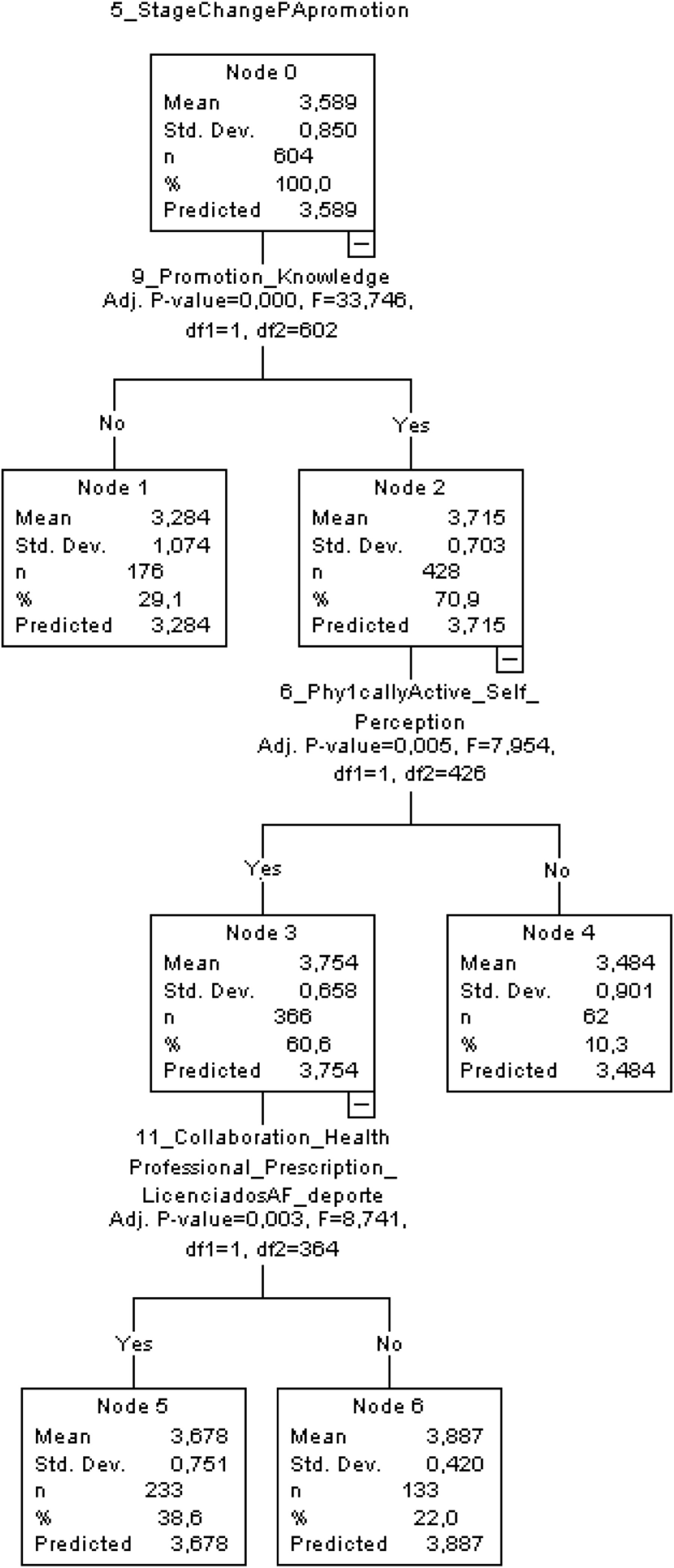

MeasurementsData were analyzed under a classification tree analysis by four predictor variables: (i) Health professional (Nurses/GPs); (ii) Exercise prescription collaboration with all health professionals: physicians, nurses, psychologists, physical therapists, sports medicine physicians, sports scientists, nutritionists, and teachers (Yes/No); (iii) PA promotion collaboration with Sports Scientists (Yes/No); and (iv) The stage of change of PHC staff to PA promotion (0–4 Likert scale).

ResultsRegarding the predictor variable (i), responders without PA guidelines knowledge and positive attitude to collaborate with nurses in PA promotion are more GPs of female sex (nurses n=33 and GPs n=175) than male sex (nurses n=3 and GPs n=59) (p<.001). For the predictor variable (ii) only 9.30% of PHC staff with a positive attitude to collaborate with all health professionals in PA promotion and exercise prescription. For the predictor variable (iii) was shown low collaboration with sports physicians and sports scientists under a multidisciplinary PAP approach (26.50% responders). Finally, in the predictor variable (iv) Staff maintaining PAP for at least 6 months, self-considered active, and with PAP knowledge want to collaborate with Sports scientists (Yes=233; No=133).

ConclusionsNurses and GPs are conscious of health-related PA benefits despite the lack of PAP knowledge and lack of willingness to collaborate with other health personnel, exercise professionals, and community resources available.

Evaluar la autopercepción de enfermeros/as y médicos/as de Atención Primaria hacia la promoción de actividad física y prescripción de ejercicio físico (PAP) en los Centros de Atención Primaria (CAP) de Madrid.

DiseñoEstudio de cohortes mediante encuesta.

EmplazamientoEnfermeros/as y médicos/as de los CAP de Madrid.

ParticipantesRespondieron 319 médicos/as y 285 enfermeros/as de CAP de Madrid.

MedicionesÁrbol de decisiones con 4 variables predictoras: i) profesionales de la salud (enfermeros/as/médicos/as); ii) colaboración con profesionales sanitarios en prescripción de ejercicio físico (respuesta: sí/no); iii) colaboración con los educadores físicos en promoción de actividad física (respuesta: sí/no), y iv) estado del cambio del comportamiento en PAP (0-4 escala de Likert).

ResultadosPara la variable predictora i), los encuestados sin conocimiento de las recomendaciones de actividad física y actitud positiva para colaborar con enfermeros/as en promoción de actividad física son más frecuentemente médicos/as del género femenino (enfermeras n=33; médicas n=175) que del masculino (enfermeros n=3; médicos n=59) (p<0,001). Para la variable predictora ii), solo un 9,30% de los profesionales desean colaborar con todos los profesionales de la salud. Para la variable predictora iii), se reflejó una baja colaboración con médicos/as deportivos y educadores físicos (26,50% de los encuestados). Finalmente, para la variable predictora iv), los profesionales que mantienen su PAP durante 6 meses, autopercibidos físicamente activos y con conocimiento en PAP, desean colaborar con los educadores físico-deportivos (sí=233; no=133).

ConclusionesLos enfermeros/as y médicos/as de los CAP son conscientes de los beneficios de la actividad física, pero poseen falta de conocimiento y concienciación para colaborar con otros profesionales y utilizar los recursos comunitarios disponibles para prescribir ejercicio físico.

Physical inactivity and sedentary levels are well known predictors of non-communicable diseases (NCDs).1 However, at least one-third of the global age-standardized worldwide population possesses insufficient physical activity levels (PAL).1 The most recent global estimates show that one in four adults and more than three-quarters of adolescents do not meet the physical activity (PA) guidelines.1 These data are currently considered as a serious health threat.1 During last decades, different Global Action Plans on Physical Activity have been implemented, such as the new Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030, approved in 2018 with a target to reduce global levels of physical inactivity in people by 15% by 2030.2 Therefore, after COVID-19 pandemic all the negative consequences of physical inactivity and sedentary behaviors for human health have got a new insight.3 And nowadays, Health-Care Systems are increasingly considered a good resource to take an active role in PA promotion.4 In this sense, it is well-known that PAP could prevent unhealthy conditions and exercise prescriptions to treat from 26 to 40 different NCDs.5,6 PAP is considered as the best medicine-drug polypill over pharmacological interventions for some NCDs.7 Besides, a higher number of patients visit Health-Care Setting each year and the evidence says that PAP is a cost-effective resource.8 A review done by Blair et al. concluded that a brief exercise training prescription counseling is efficient, effective, and cost-effective.9

However, some authors indicate that lack of resources in the Health-Care System is an issue in implementing an efficient PAP.8,10 Several barriers have been mentioned in the scientific literature such as lack of knowledge and training about exercise prescription, inefficient network team, having not enough time, individualized interventions in research and clinical settings, among others, that could lead to the reduced PAP in the Primary Health-Care (PHC) Settings.11,12 For all these factors, evidence of specific strategies with greater effectiveness is still needed to enhance the implementation.8 In this way, these multifactorial issues could be analyzed by a classification tree analysis (CHAID) to know which variable or combination of variables, better predicts PHC barriers and facilitators for PAP in a specific context.13 In the last years, there have been many different initiatives support introducing PAP at PHC,14 many of them, without a previous analysis for their design and implementation. For that reason, the implementation of PAP in Health-Care Settings is not without difficulties and worldwide problems and worthwhile to enhance.8,15 Besides, previously, Desveaux et al. in 2016, observed discrepancies between the barriers perceived by patients and by PHC providers to a community-based exercise program measured by a questionnaire.16 In 2016, Short et al. showed that only one-fifth of participants from their survey sample reported receiving PAP recommendation from their physicians.17 The patients that received PAP recommendation were those who scored higher in physical health-related quality of life.17 PA counseling, as part of routine healthcare delivery, is one of the best ways to promote healthy lifestyle habits and to provoke behavior changes improving health and quality of life in patients.18 In this way, this study aims to assess the self-perception of nurses and GPs toward PAP in Madrid PHC.

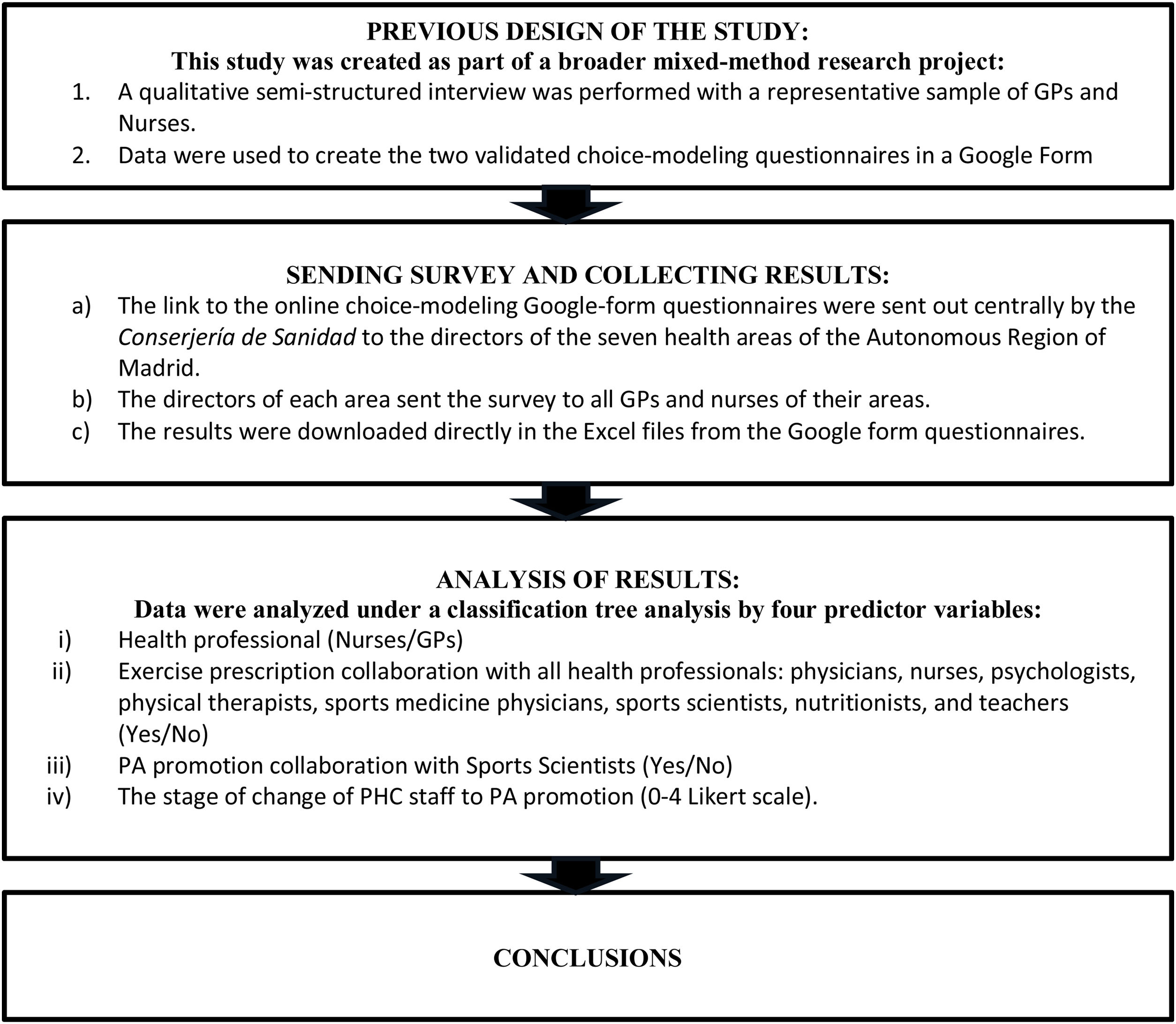

Material and methodsThis study was created as part of a broader mixed-method (complex mixed design) research project.14 In the first stage, a qualitative semi-structured interview was performed with a representative sample of GPs and Nurses.19 These data were used to create two validated questionnaires.20 Finally, by this study we tested the questionnaire's items with a total of 319 GPs (76.50% females) and 285 nurses (88.40% females) with 23.68 (8.55) y and 25.51(10.84) y of PHC career experience, respectively, who were working at PHC in the Autonomous Region of Madrid.

The link to the online choice-modeling Google-form questionnaires were sent out centrally by the Conserjería de Sanidad to the directors of the seven health areas in which the Autonomous Region of Madrid is split into. These directors sent it to all GPs and nurses of their area. The results were downloaded directly in the Excel files from the Google form questionnaires. Link to the questionnaires for nurses: https://forms.gle/CmJDQAjR5Pt1zLp36; and GPs: https://forms.gle/coQttEgtBPYgH7Qj7 were sent via email, previous consent to participate.

Data collection took place between October 2018 and December 2018.

The dependent variables in the fourth processes were: (i) Health professional (Nurses/GPs); (ii) Exercise prescription collaboration with all health professionals: physicians, nurses, psychologists, physical therapists, sports medicine physicians, sports scientists, nutritionists, and teachers (Yes/No); (iii) PA promotion collaboration with Sports Scientists (Yes/No); and (iv) The stage of change of PHC staff to PA promotion (0–4 Likert scale). The dependent variable of this last process, according to the transtheoretical model, assumes that behavior change is a dynamic process, which occurs through a temporal dimension in a sequence of stages: (a). No PAP; (b). Purpose to PAP in the next months; (c). Current training and willingness about PAP; (d). Maintaining the PAP routine with their patients for less than 6 months; (e). Maintaining the PAP routine with their patients for more than 6 months. By these stages, the health professionals move until reaching regular PAP behavior with their patients.

The independent variables were related to the questionnaire's items. For the process i, ii and iii: there were selected items 1, 2 (both of them), 3 (binary category), 5 (0–4 level), 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13 (all of them), 14, 16 (all of them), 17, 18 (all of them), 19, 20, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29 (all of them), 30 (all of them), sex, and working years at PHC System (binary category by ≤20 yr. or >20 yr.); and for the process IV, besides of the previous ones, age range variable was added (20-30 yr., 31-40 yr., 41-50 yr., 51-60 yr., 61-70 yr.). Predictor variables were changed in each model for independent variables of other processes.

Regarding the statistical analysis process, firstly, a descriptive and inferential analysis was performed using the crosstabs command. The Pearson's Chi-squared test, was used to analyze the effects between PHC staff (nurses and GPS) and all independent variables related to PAP collaboration. The odds ratio (OR) by the risk of the previouslymentioned test (95% confidence interval, CI). Some results were categorized by PHC areas, sex, age range and professional status, and corrected by the Fisher test for the lower frequency rates of answer of questionnaires’ items 13, 16 and 18.

Effect sizes (ES) were calculated using the Cramer's V test and their interpretation was based on this criteria: 0.10=small effect, 0.30=medium effect, and 0.50=large effect.13

Secondly, a classification tree analysis was used to determine the classification of which variable or combination of independent variables previously mentioned was used to better predict self-perceived context by nurses and GPs for future implementation of a PAP at PHC Settings in the region of Madrid. This technique allows splitting the sample into different subgroups (nodes) based on the impact of predictions (independent variables).

The exhaustive CHAID (Chi-squared automatic Interaction detection) was the algorithm used, appropriate to nominal dependent and nominal and metric independent 3 variables.

The Chi-square test identifies the relationships between independent variables by completing three steps on each node of the root to find the predictors that exert the highest influence on the predictor variable. The exhaustive CHAID checks all possible splits for each predictor and the merging step increases the search procedure to merge any similar pair until only a single pair remains. Furthermore, all these statistical specifications were considered: (i) the tree has a maximum of 3 levels; (ii) the Pearson's Chi-square was used to detect the relationships between independent variables; (iii) 100 were the maximum number of iterations; (iv) the minimum change in expected cell frequencies is 0.001; (v) significant level was set at p<.05; and (vi) the Bonferroni method was used to significant values adjustments.13

The statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0 for Windows (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0, Chicago, IL, USA, NY: IBM Corp.).

The study was performed according to the principles established with the Declaration of Helsinki 1964 and further amendments and other national regulations for research projects involving human participants: Protection of Personal Data, Law 15/1999 of 13 December on the Protection of Personal Data provided in the current legislation (Royal Decree 1720/2007 of 21 December). The protocol study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the “Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón” and the Central Commission for research of the Region of Madrid with the protocol code: 42/17; ID:RP1811600040 (date: 13/12/2017) and the informed consent of all participants.

General outline of the study: Scheme of the study.

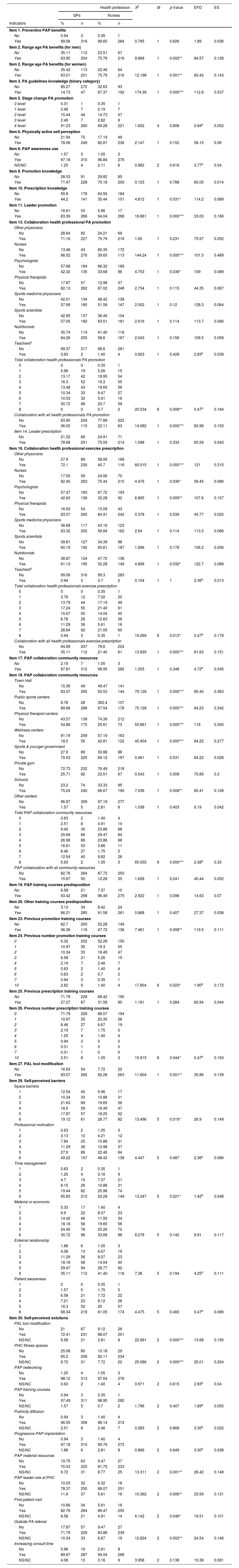

ResultsThe sample was obtained from a total of 3850 GPs and 3547 nurses, getting a total of 319 GPs’ responses (response rate: 8.28%) and 285 nurses’ responses (response rate: 8.03%) (Table 1).

Frequency distribution (%) of the nurses and GPs responders of Madrid PHC according to questionnaire indicators (Crosstab Command: Pearson's Chi-square, degrees of freedom, significance, expected frequency distribution, and effect size).

| Health profession | X2 | df | p-Value | EFD | ES | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPs | Nurses | ||||||||

| Indicators | % | n | % | n | |||||

| Item 1. Preventive PAP benefits | |||||||||

| No | 0.94 | 3 | 0.35 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 99.06 | 316 | 99.65 | 284 | 0.795 | 1 | 0.626 | 1.89 | 0.036 |

| Item 2. Range age PA benefits (for men) | |||||||||

| No | 35.11 | 112 | 23.51 | 67 | |||||

| Yes | 63.95 | 204 | 75.79 | 216 | 9.868 | 1 | 0.002** | 84.57 | 0.128 |

| Item 2. Range age PA benefits (for women) | |||||||||

| No | 35.42 | 113 | 22.46 | 64 | |||||

| Yes | 63.01 | 201 | 75.79 | 216 | 12.198 | 1 | 0.001** | 83.43 | 0.143 |

| Item 3. PA guidelines knowledge (binary category) | |||||||||

| No | 85.27 | 272 | 32.63 | 93 | |||||

| Yes | 14.73 | 47 | 67.37 | 192 | 174.39 | 1 | 0.000*** | 112.8 | 0.537 |

| Item 5. Stage change PA promotion | |||||||||

| 0 level | 0.31 | 1 | 0.35 | 1 | |||||

| 1 level | 2.46 | 7 | 2.19 | 7 | |||||

| 2 level | 15.44 | 44 | 14.73 | 47 | |||||

| 3 level | 2.46 | 7 | 2.82 | 9 | |||||

| 4 level | 91.23 | 260 | 69.28 | 221 | 1.602 | 4 | 0.808 | 0.94b | 0.052 |

| Item 6. Physically active self perception | |||||||||

| No | 21.94 | 70 | 17.19 | 49 | |||||

| Yes | 78.06 | 249 | 82.81 | 236 | 2.147 | 1 | 0.152 | 56.15 | 0.06 |

| Item 8. PAP awareness use | |||||||||

| No | 1.57 | 5 | 1.05 | 3 | |||||

| Yes | 97.18 | 310 | 96.84 | 276 | |||||

| NS/NC | 1.25 | 4 | 2.11 | 6 | 0.962 | 2 | 0.618 | 3.77b | 0.04 |

| Item 9. Promotion knowledge | |||||||||

| No | 28.53 | 91 | 29.82 | 85 | |||||

| Yes | 71.47 | 228 | 70.18 | 200 | 0.123 | 1 | 0.788 | 83.05 | 0.014 |

| Item 10. Prescription knowledge | |||||||||

| No | 55.8 | 178 | 64.56 | 184 | |||||

| Yes | 44.2 | 141 | 35.44 | 101 | 4.812 | 1 | 0.031* | 114.2 | 0.089 |

| Item 11. Leader promotion | |||||||||

| No | 16.61 | 53 | 5.96 | 17 | |||||

| Yes | 83.39 | 266 | 94.04 | 268 | 16.661 | 1 | 0.000*** | 33.03 | 0.166 |

| Item 13. Collaboration health professional PA promotion | |||||||||

| Other physicians | |||||||||

| No | 28.84 | 92 | 24.21 | 69 | |||||

| Yes | 71.16 | 227 | 75.79 | 216 | 1.65 | 1 | 0.231 | 75.97 | 0.052 |

| Nurses | |||||||||

| No | 13.48 | 43 | 60.35 | 172 | |||||

| Yes | 86.52 | 276 | 39.65 | 113 | 144.24 | 1 | 0.000*** | 101.5 | 0.489 |

| Psychologists | |||||||||

| No | 57.68 | 184 | 66.32 | 189 | |||||

| Yes | 42.32 | 135 | 33.68 | 96 | 4.753 | 1 | 0.036* | 109 | 0.089 |

| Physical therapists | |||||||||

| No | 17.87 | 57 | 12.98 | 37 | |||||

| Yes | 82.13 | 262 | 87.02 | 248 | 2.734 | 1 | 0.115 | 44.35 | 0.067 |

| Sports medicine physicians | |||||||||

| No | 42.01 | 134 | 48.42 | 138 | |||||

| Yes | 57.99 | 185 | 51.58 | 147 | 2.502 | 1 | 0.12 | 128.3 | 0.064 |

| Sports scientists | |||||||||

| No | 42.95 | 137 | 36.49 | 104 | |||||

| Yes | 57.05 | 182 | 63.51 | 181 | 2.616 | 1 | 0.114 | 113.7 | 0.066 |

| Nutritionists | |||||||||

| No | 35.74 | 114 | 41.40 | 118 | |||||

| Yes | 64.26 | 205 | 58.6 | 167 | 2.043 | 1 | 0.156 | 109.5 | 0.058 |

| Teachersa | |||||||||

| No | 99.37 | 317 | 98.6 | 281 | |||||

| Yes | 0.63 | 2 | 1.40 | 4 | 0.923 | 1 | 0.428 | 2.83b | 0.039 |

| Total collaboration health professionals PA promotion | |||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.35 | 1 | |||||

| 1 | 5.96 | 19 | 5.26 | 15 | |||||

| 2 | 13.17 | 42 | 18.95 | 54 | |||||

| 3 | 16.3 | 52 | 19.3 | 55 | |||||

| 4 | 13.48 | 43 | 19.65 | 56 | |||||

| 5 | 10.34 | 33 | 9.47 | 27 | |||||

| 6 | 10.03 | 32 | 5.61 | 16 | |||||

| 7 | 30.72 | 98 | 20.7 | 59 | |||||

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 2 | 20.534 | 8 | 0.008** | 0.47b | 0.184 |

| Collaboration with all health professionals PA promotion | |||||||||

| No | 63.95 | 204 | 77.89 | 222 | |||||

| Yes | 36.05 | 115 | 22.11 | 63 | 14.082 | 1 | 0.000*** | 83.99 | 0.153 |

| Item 14. Leader prescription | |||||||||

| No | 21.32 | 68 | 24.91 | 71 | |||||

| Yes | 78.68 | 251 | 75.09 | 214 | 1.098 | 1 | 0.333 | 65.59 | 0.043 |

| Item 16. Collaboration health professional exercise prescription | |||||||||

| Other physicians | |||||||||

| No | 27.9 | 89 | 58.95 | 168 | |||||

| Yes | 72.1 | 230 | 40.7 | 116 | 60.015 | 1 | 0.000*** | 121 | 0.315 |

| Nurses | |||||||||

| No | 17.55 | 56 | 24.56 | 70 | |||||

| Yes | 82.45 | 263 | 75.44 | 215 | 4.476 | 1 | 0.036* | 59.45 | 0.086 |

| Psychologists | |||||||||

| No | 57.37 | 183 | 67.72 | 193 | |||||

| Yes | 42.63 | 136 | 32.28 | 92 | 6.865 | 1 | 0.009** | 107.6 | 0.107 |

| Physical therapists | |||||||||

| No | 16.93 | 54 | 15.09 | 43 | |||||

| Yes | 83.07 | 265 | 84.91 | 242 | 0.378 | 1 | 0.539 | 45.77 | 0.025 |

| Sports medicine physicians | |||||||||

| No | 36.68 | 117 | 43.16 | 123 | |||||

| Yes | 63.32 | 202 | 56.84 | 162 | 2.64 | 1 | 0.114 | 113.3 | 0.066 |

| Sports scientists | |||||||||

| No | 39.81 | 127 | 34.39 | 98 | |||||

| Yes | 60.19 | 192 | 65.61 | 187 | 1.896 | 1 | 0.178 | 106.2 | 0.056 |

| Nutritionists | |||||||||

| No | 38.87 | 124 | 47.72 | 136 | |||||

| Yes | 61.13 | 195 | 52.28 | 149 | 4.806 | 1 | 0.032* | 122.7 | 0.089 |

| Teachersa | |||||||||

| No | 99.06 | 316 | 99.3 | 283 | |||||

| Yes | 0.94 | 3 | 0.7 | 2 | 0.104 | 1 | 1 | 2.36b | 0.013 |

| Total collaboration health professionals exercise prescription | |||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.35 | 1 | |||||

| 1 | 3.76 | 12 | 7.02 | 20 | |||||

| 2 | 13.79 | 44 | 17.19 | 49 | |||||

| 3 | 17.24 | 55 | 21.40 | 61 | |||||

| 4 | 15.67 | 50 | 14.04 | 40 | |||||

| 5 | 8.78 | 28 | 12.63 | 36 | |||||

| 6 | 11.29 | 36 | 5.61 | 16 | |||||

| 7 | 28.84 | 92 | 21.05 | 60 | |||||

| 8 | 0.94 | 3 | 0.35 | 1 | 19.269 | 8 | 0.013* | 0.47b | 0.179 |

| Collaboration with all health professionals exercise prescription | |||||||||

| No | 64.89 | 207 | 78.6 | 224 | |||||

| Yes | 35.11 | 112 | 21.40 | 61 | 13.835 | 1 | 0.000*** | 81.63 | 0.151 |

| Item 17. PAP collaboration community resources | |||||||||

| No | 2.19 | 7 | 1.05 | 3 | |||||

| Yes | 97.81 | 312 | 98.95 | 282 | 1.205 | 1 | 0.348 | 4.72b | 0.045 |

| Item 18. PAP collaboration community resources | |||||||||

| Town Hall | |||||||||

| No | 15.36 | 49 | 49.47 | 141 | |||||

| Yes | 83.07 | 265 | 50.53 | 144 | 79.126 | 1 | 0.000*** | 90.40 | 0.363 |

| Public sports centers | |||||||||

| No | 8.78 | 28 | 362.4 | 107 | |||||

| Yes | 89.66 | 286 | 67.54 | 178 | 70.128 | 1 | 0.000*** | 64.23 | 0.342 |

| Physical therapist centers | |||||||||

| No | 43.57 | 139 | 74.39 | 212 | |||||

| Yes | 54.86 | 175 | 25.61 | 73 | 55.861 | 1 | 0.000*** | 118 | 0.305 |

| Wellness centers | |||||||||

| No | 81.19 | 259 | 57.19 | 163 | |||||

| Yes | 18.5 | 55 | 42.81 | 122 | 45.904 | 1 | 0.000*** | 84.22 | 0.277 |

| Sports & younger government | |||||||||

| No | 27.9 | 89 | 30.88 | 88 | |||||

| Yes | 70.53 | 225 | 69.12 | 197 | 0.461 | 1 | 0.531 | 84.22 | 0.028 |

| Private gym | |||||||||

| No | 72.73 | 232 | 76.49 | 218 | |||||

| Yes | 25.71 | 82 | 23.51 | 67 | 0.543 | 1 | 0.508 | 70.89 | 0.3 |

| Schools | |||||||||

| No | 23.2 | 74 | 33.33 | 95 | |||||

| Yes | 75.24 | 240 | 66.67 | 190 | 7.036 | 1 | 0.008** | 80.41 | 0.108 |

| Other centers | |||||||||

| No | 96.87 | 309 | 97.19 | 277 | |||||

| Yes | 1.57 | 5 | 2.81 | 8 | 1.038 | 1 | 0.403 | 6.19 | 0.042 |

| Total PAP collaboration community resources: | |||||||||

| 0 | 0.63 | 2 | 1.40 | 4 | |||||

| 1 | 2.51 | 8 | 4.91 | 14 | |||||

| 2 | 9.40 | 30 | 23.86 | 68 | |||||

| 3 | 20.69 | 66 | 29.47 | 84 | |||||

| 4 | 26.96 | 86 | 23.86 | 68 | |||||

| 5 | 16.61 | 53 | 3.86 | 11 | |||||

| 6 | 8.46 | 27 | 1.75 | 5 | |||||

| 7 | 12.54 | 40 | 9.82 | 28 | |||||

| 8 | 0.63 | 2 | 1.05 | 3 | 65.055 | 8 | 0.000*** | 2.38b | 0.33 |

| PAP collaboration with all community resources | |||||||||

| No | 82.76 | 264 | 87.72 | 250 | |||||

| Yes | 15.67 | 50 | 12.28 | 35 | 1.628 | 1 | 0.241 | 40.44 | 0.052 |

| Item 19. PAP training courses predisposition | |||||||||

| No | 6.58 | 21 | 7.37 | 10 | |||||

| Yes | 93.42 | 298 | 96.49 | 275 | 2.922 | 1 | 0.098 | 14.63 | 0.07 |

| Item 20. Other training courses predisposition | |||||||||

| No | 3.13 | 34 | 8.42 | 24 | |||||

| Yes | 86.21 | 285 | 91.58 | 261 | 0.868 | 1 | 0.407 | 27.37 | 0.038 |

| Item 23. Previous promotion training courses | |||||||||

| No | 62.7 | 200 | 52.28 | 149 | |||||

| Yes | 36.36 | 116 | 47.72 | 136 | 7.461 | 1 | 0.008** | 119.5 | 0.111 |

| Item 24. Previous number promotion training courses | |||||||||

| 0 | 6.32 | 202 | 52.28 | 150 | |||||

| 1 | 10.97 | 35 | 19.3 | 55 | |||||

| 2 | 10.34 | 33 | 16.49 | 47 | |||||

| 3 | 6.58 | 21 | 5.26 | 15 | |||||

| 4 | 2.19 | 7 | 2.46 | 7 | |||||

| 5 | 0.63 | 2 | 1.40 | 4 | |||||

| 6 | 0.63 | 2 | 0.7 | 2 | |||||

| 7 | 0.94 | 3 | 0.35 | 1 | |||||

| 10 | 2.82 | 9 | 1.40 | 4 | 17.804 | 8 | 0.023* | 1.90b | 0.172 |

| Item 25. Previous prescription training courses | |||||||||

| No | 71.79 | 229 | 68.42 | 195 | |||||

| Yes | 27.27 | 87 | 31.58 | 90 | 1.181 | 1 | 0.284 | 83.94 | 0.044 |

| Item 26. Previous number prescription training courses | |||||||||

| 0 | 71.79 | 229 | 68.07 | 194 | |||||

| 1 | 10.97 | 35 | 20.35 | 58 | |||||

| 2 | 8.46 | 27 | 6.67 | 19 | |||||

| 3 | 2.19 | 7 | 1.75 | 5 | |||||

| 4 | 1.25 | 4 | 1.40 | 4 | |||||

| 5 | 0.94 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 6 | 0.31 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 7 | 0.31 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 10 | 2.51 | 8 | 1.05 | 3 | 15.915 | 8 | 0.044* | 0.47b | 0.163 |

| Item 27. PAL tool modification | |||||||||

| No | 16.93 | 54 | 7.72 | 22 | |||||

| Yes | 83.07 | 265 | 92.28 | 263 | 11.604 | 1 | 0.001** | 35.86 | 0.139 |

| Item 29. Self-perceived barriers | |||||||||

| Space barriers | |||||||||

| 1 | 12.54 | 40 | 5.96 | 17 | |||||

| 2 | 10.34 | 33 | 10.88 | 31 | |||||

| 3 | 21.63 | 69 | 19.65 | 56 | |||||

| 4 | 18.5 | 59 | 16.49 | 47 | |||||

| 5 | 17.87 | 57 | 18.25 | 52 | |||||

| 6 | 19.12 | 61 | 28.77 | 82 | 13.496 | 5 | 0.019* | 26.9 | 0.149 |

| Professional motivation | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.63 | 2 | 1.05 | 3 | |||||

| 2 | 3.13 | 10 | 4.21 | 12 | |||||

| 3 | 7.84 | 25 | 10.88 | 31 | |||||

| 4 | 11.29 | 36 | 12.98 | 37 | |||||

| 5 | 27.9 | 89 | 22.46 | 64 | |||||

| 6 | 49.22 | 157 | 48.42 | 138 | 4.447 | 5 | 0.487 | 2.36b | 0.086 |

| Time management | |||||||||

| 1 | 0.63 | 2 | 0.35 | 1 | |||||

| 2 | 1.25 | 4 | 3.16 | 9 | |||||

| 3 | 4.7 | 15 | 7.37 | 21 | |||||

| 4 | 8.15 | 26 | 10.88 | 31 | |||||

| 5 | 19.44 | 62 | 25.96 | 74 | |||||

| 6 | 65.83 | 210 | 52.28 | 149 | 13.247 | 5 | 0.021* | 1.42b | 0.048 |

| Material or economic | |||||||||

| 1 | 5.33 | 17 | 1.40 | 4 | |||||

| 2 | 6.9 | 22 | 8.07 | 23 | |||||

| 3 | 14.42 | 46 | 11.93 | 34 | |||||

| 4 | 18.18 | 58 | 19.65 | 56 | |||||

| 5 | 24.45 | 78 | 25.26 | 72 | |||||

| 6 | 30.72 | 98 | 33.68 | 96 | 8.278 | 5 | 0.142 | 9.91 | 0.117 |

| External relationship | |||||||||

| 1 | 1.88 | 6 | 1.05 | 3 | |||||

| 2 | 4.08 | 13 | 6.67 | 19 | |||||

| 3 | 11.29 | 36 | 8.07 | 23 | |||||

| 4 | 18.18 | 58 | 14.04 | 40 | |||||

| 5 | 29.47 | 94 | 28.77 | 82 | |||||

| 6 | 35.11 | 112 | 41.40 | 118 | 7.38 | 5 | 0.194 | 4.25b | 0.111 |

| Patient awareness | |||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.35 | 1 | |||||

| 2 | 1.57 | 5 | 1.75 | 5 | |||||

| 3 | 6.58 | 21 | 7.72 | 22 | |||||

| 4 | 7.21 | 23 | 9.12 | 26 | |||||

| 5 | 16.3 | 52 | 20 | 57 | |||||

| 6 | 68.34 | 218 | 61.05 | 174 | 4.475 | 5 | 0.483 | 0.47b | 0.086 |

| Item 30. Self-perceived solutions | |||||||||

| PAL tool modification | |||||||||

| No | 21 | 67 | 9.12 | 26 | |||||

| Yes | 72.41 | 231 | 88.07 | 251 | |||||

| NS/NC | 6.58 | 21 | 2.81 | 8 | 22.891 | 2 | 0.000*** | 13.68 | 0.195 |

| PHC fitness spaces | |||||||||

| No | 25.08 | 80 | 10.18 | 29 | |||||

| Yes | 65.2 | 208 | 82.11 | 234 | |||||

| NS/NC | 9.72 | 31 | 7.72 | 22 | 25.086 | 2 | 0.000*** | 25.01 | 0.204 |

| PAP networking | |||||||||

| No | 1.25 | 4 | 1.05 | 3 | |||||

| Yes | 98.12 | 313 | 97.54 | 278 | |||||

| NS/NC | 0.63 | 2 | 1.40 | 4 | 0.971 | 2 | 0.615 | 2.83b | 0.04 |

| PAP training courses | |||||||||

| No | 0.94 | 3 | 0.35 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 97.49 | 311 | 98.95 | 282 | |||||

| NS/NC | 1.57 | 5 | 0.7 | 2 | 1.796 | 2 | 0.407 | 1.89b | 0.055 |

| Publicity diffusion | |||||||||

| No | 0.94 | 3 | 1.40 | 4 | |||||

| Yes | 96.55 | 308 | 96.14 | 274 | |||||

| NS/NC | 2.51 | 8 | 2.46 | 7 | 0.283 | 2 | 0.868 | 3.30b | 0.022 |

| Progressive PAP implantation | |||||||||

| No | 0.94 | 3 | 1.40 | 4 | |||||

| Yes | 97.18 | 310 | 95.79 | 273 | |||||

| NS/NC | 1.88 | 6 | 2.81 | 8 | 0.866 | 2 | 0.649 | 3.30b | 0.038 |

| PAP material resources | |||||||||

| No | 19.75 | 63 | 9.47 | 27 | |||||

| Yes | 70.53 | 225 | 81.75 | 233 | |||||

| NS/NC | 9.72 | 31 | 8.77 | 25 | 13.311 | 2 | 0.001** | 26.42 | 0.148 |

| PAP leader role at PHC | |||||||||

| No | 10.03 | 32 | 6.32 | 18 | |||||

| Yes | 78.37 | 250 | 88.07 | 251 | |||||

| NS/NC | 11.6 | 37 | 5.61 | 16 | 10.362 | 2 | 0.006** | 23.59 | 0.131 |

| First patient visit | |||||||||

| No | 10.66 | 34 | 5.61 | 16 | |||||

| Yes | 82.76 | 264 | 89.47 | 255 | |||||

| NS/NC | 6.58 | 21 | 4.91 | 14 | 6.142 | 2 | 0.046* | 16.51 | 0.101 |

| Outside PA referral | |||||||||

| No | 17.87 | 57 | 9.47 | 27 | |||||

| Yes | 71.79 | 229 | 83.86 | 239 | |||||

| NS/NC | 10.34 | 33 | 6.67 | 19 | 12.824 | 2 | 0.002** | 24.54 | 0.146 |

| Increasing consult time | |||||||||

| No | 5.96 | 19 | 2.81 | 8 | |||||

| Yes | 89.97 | 287 | 94.04 | 268 | |||||

| NS/NC | 4.08 | 13 | 3.16 | 9 | 3.958 | 2 | 0.138 | 10.38 | 0.081 |

GPs: general practitioners; df: degrees of freedom; EFD: expected frequency distribution; ES: effect size; PA: physical activity; PAP: physical activity on prescription; PAL: physical activity levels; NS/NC: do not know, no answer.

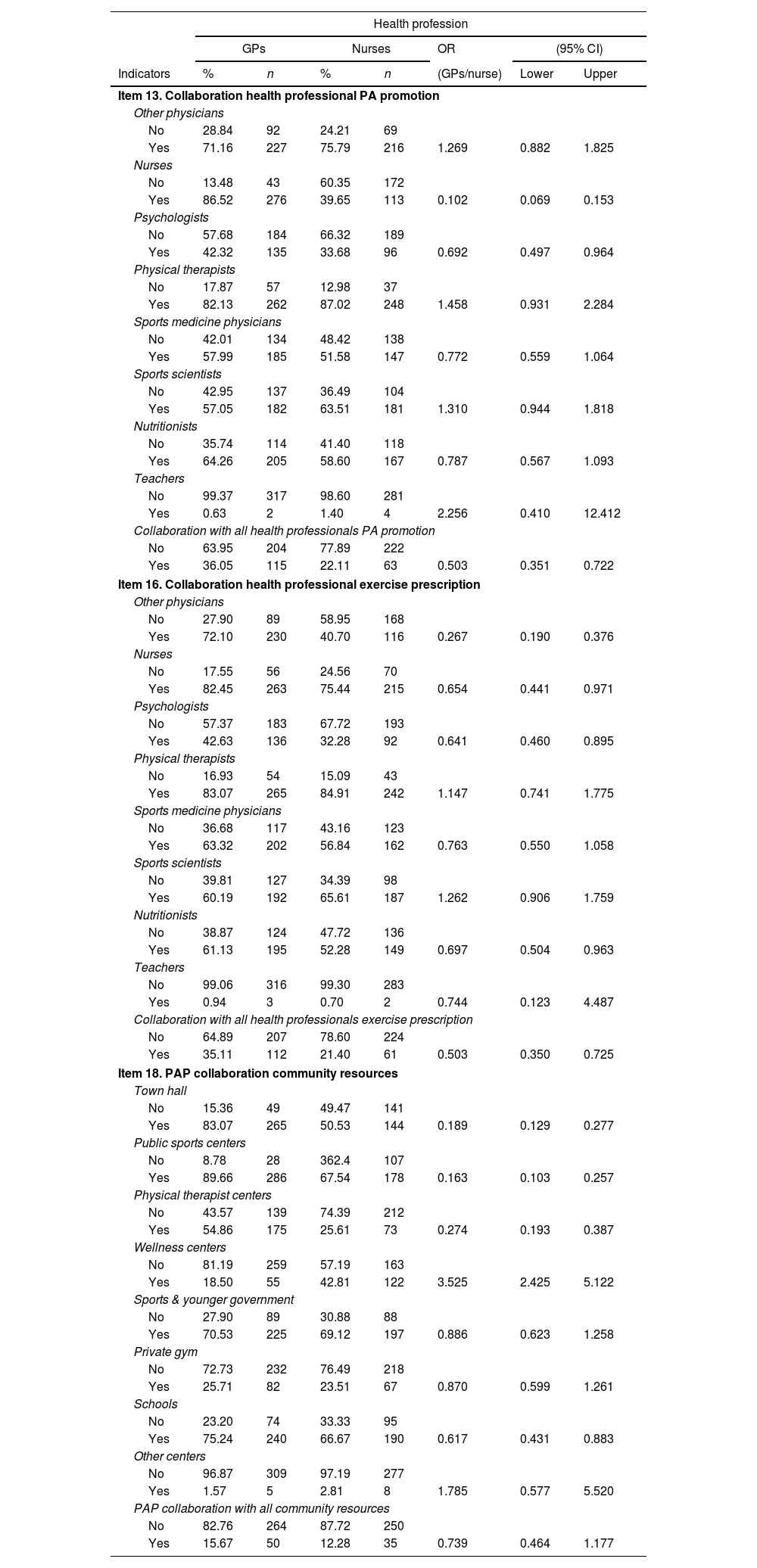

The odds ratio in the collaboration on PA promotion, exercise prescription and community resources adjusted by PHC staff (nurses and GPs) is shown in Table 2.

The odds ratio (OR) between PHC staff (nurses and GPS) in collaboration on PA promotion, exercise prescription and community resources (95% confidence interval, CI).

| Health profession | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPs | Nurses | OR | (95% CI) | ||||

| Indicators | % | n | % | n | (GPs/nurse) | Lower | Upper |

| Item 13. Collaboration health professional PA promotion | |||||||

| Other physicians | |||||||

| No | 28.84 | 92 | 24.21 | 69 | |||

| Yes | 71.16 | 227 | 75.79 | 216 | 1.269 | 0.882 | 1.825 |

| Nurses | |||||||

| No | 13.48 | 43 | 60.35 | 172 | |||

| Yes | 86.52 | 276 | 39.65 | 113 | 0.102 | 0.069 | 0.153 |

| Psychologists | |||||||

| No | 57.68 | 184 | 66.32 | 189 | |||

| Yes | 42.32 | 135 | 33.68 | 96 | 0.692 | 0.497 | 0.964 |

| Physical therapists | |||||||

| No | 17.87 | 57 | 12.98 | 37 | |||

| Yes | 82.13 | 262 | 87.02 | 248 | 1.458 | 0.931 | 2.284 |

| Sports medicine physicians | |||||||

| No | 42.01 | 134 | 48.42 | 138 | |||

| Yes | 57.99 | 185 | 51.58 | 147 | 0.772 | 0.559 | 1.064 |

| Sports scientists | |||||||

| No | 42.95 | 137 | 36.49 | 104 | |||

| Yes | 57.05 | 182 | 63.51 | 181 | 1.310 | 0.944 | 1.818 |

| Nutritionists | |||||||

| No | 35.74 | 114 | 41.40 | 118 | |||

| Yes | 64.26 | 205 | 58.60 | 167 | 0.787 | 0.567 | 1.093 |

| Teachers | |||||||

| No | 99.37 | 317 | 98.60 | 281 | |||

| Yes | 0.63 | 2 | 1.40 | 4 | 2.256 | 0.410 | 12.412 |

| Collaboration with all health professionals PA promotion | |||||||

| No | 63.95 | 204 | 77.89 | 222 | |||

| Yes | 36.05 | 115 | 22.11 | 63 | 0.503 | 0.351 | 0.722 |

| Item 16. Collaboration health professional exercise prescription | |||||||

| Other physicians | |||||||

| No | 27.90 | 89 | 58.95 | 168 | |||

| Yes | 72.10 | 230 | 40.70 | 116 | 0.267 | 0.190 | 0.376 |

| Nurses | |||||||

| No | 17.55 | 56 | 24.56 | 70 | |||

| Yes | 82.45 | 263 | 75.44 | 215 | 0.654 | 0.441 | 0.971 |

| Psychologists | |||||||

| No | 57.37 | 183 | 67.72 | 193 | |||

| Yes | 42.63 | 136 | 32.28 | 92 | 0.641 | 0.460 | 0.895 |

| Physical therapists | |||||||

| No | 16.93 | 54 | 15.09 | 43 | |||

| Yes | 83.07 | 265 | 84.91 | 242 | 1.147 | 0.741 | 1.775 |

| Sports medicine physicians | |||||||

| No | 36.68 | 117 | 43.16 | 123 | |||

| Yes | 63.32 | 202 | 56.84 | 162 | 0.763 | 0.550 | 1.058 |

| Sports scientists | |||||||

| No | 39.81 | 127 | 34.39 | 98 | |||

| Yes | 60.19 | 192 | 65.61 | 187 | 1.262 | 0.906 | 1.759 |

| Nutritionists | |||||||

| No | 38.87 | 124 | 47.72 | 136 | |||

| Yes | 61.13 | 195 | 52.28 | 149 | 0.697 | 0.504 | 0.963 |

| Teachers | |||||||

| No | 99.06 | 316 | 99.30 | 283 | |||

| Yes | 0.94 | 3 | 0.70 | 2 | 0.744 | 0.123 | 4.487 |

| Collaboration with all health professionals exercise prescription | |||||||

| No | 64.89 | 207 | 78.60 | 224 | |||

| Yes | 35.11 | 112 | 21.40 | 61 | 0.503 | 0.350 | 0.725 |

| Item 18. PAP collaboration community resources | |||||||

| Town hall | |||||||

| No | 15.36 | 49 | 49.47 | 141 | |||

| Yes | 83.07 | 265 | 50.53 | 144 | 0.189 | 0.129 | 0.277 |

| Public sports centers | |||||||

| No | 8.78 | 28 | 362.4 | 107 | |||

| Yes | 89.66 | 286 | 67.54 | 178 | 0.163 | 0.103 | 0.257 |

| Physical therapist centers | |||||||

| No | 43.57 | 139 | 74.39 | 212 | |||

| Yes | 54.86 | 175 | 25.61 | 73 | 0.274 | 0.193 | 0.387 |

| Wellness centers | |||||||

| No | 81.19 | 259 | 57.19 | 163 | |||

| Yes | 18.50 | 55 | 42.81 | 122 | 3.525 | 2.425 | 5.122 |

| Sports & younger government | |||||||

| No | 27.90 | 89 | 30.88 | 88 | |||

| Yes | 70.53 | 225 | 69.12 | 197 | 0.886 | 0.623 | 1.258 |

| Private gym | |||||||

| No | 72.73 | 232 | 76.49 | 218 | |||

| Yes | 25.71 | 82 | 23.51 | 67 | 0.870 | 0.599 | 1.261 |

| Schools | |||||||

| No | 23.20 | 74 | 33.33 | 95 | |||

| Yes | 75.24 | 240 | 66.67 | 190 | 0.617 | 0.431 | 0.883 |

| Other centers | |||||||

| No | 96.87 | 309 | 97.19 | 277 | |||

| Yes | 1.57 | 5 | 2.81 | 8 | 1.785 | 0.577 | 5.520 |

| PAP collaboration with all community resources | |||||||

| No | 82.76 | 264 | 87.72 | 250 | |||

| Yes | 15.67 | 50 | 12.28 | 35 | 0.739 | 0.464 | 1.177 |

GPs: general practitioners; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; PA: physical activity; PAP: physical activity on prescription.

According to the tree analysis process I, for the (Nurses/GPs) health professional predictor variable the results showed 13 nodes defined by the classification tree analysis (Fig. 1).

Level 1 (root node) is (Yes/No) knowledge about PA guidelines by the PHC responders. Low PA guidelines knowledge was achieved by the responders (node 1: 60.4%; nurses n=93 and GPs n=272) with higher level of PHC staff without PA guidelines knowledge (node 2: 39.6%; nurses n=192 and GPs n=47), with significant differences with the predictor variable (p<.001).

At level 2, there was higher PA promotion collaboration with nurses for responders without PA guidelines knowledge at the previous level. With high level in favor of collaboration between responders (node 3, 44.70%; nurses n=36 and GPs n=234) against non-collaborators of this level (p<.001).

At level 3, there were significant differences by sex (p<.001) according to the mentioned interaction and way of this tree analysis. In this sense, female responders without PA guidelines knowledge and positive attitude to collaborate with nurses in PA promotion are more female sex (node 7; 34.40%; female nurses n=33 and female GPs n=175) than male sex (node 8; 10.30%; male nurses n=3 and male GPs n=59).

This classification tree model enabled explaining 80.30% of the total variance.

In this analysis, it is important to highlight that from the total PHC staff analyzed only 80.3% of nurses and 19.7% of GPs knew current WHO PA guidelines.

In the tree analysis process II, for the (Yes/No) collaboration with all health professionals in the exercise prescription predictor variable, the results showed 9 nodes defined by the classification tree analysis (Fig. 2).

Level 1 (root node) is PA promotion collaboration with all health professionals (node 1: 29.50%; Yes n=156 and No n=22) and non-collaboration with all health professionals (node 2: 70.50%; Yes n=17 and No n=409), having significant differences (p<.001).

At level 2 was significant differences between both groups and the predictor variable (p<.001), with low collaboration with all PAP community resources (node 3: 9.30%; Yes n=54 and No n=2). According to the previous variables analyzed in the tree analysis, only 9.30% of PHC staff with a positive attitude to collaborate with all PAP community resources and all health professionals in PA promotion and exercise prescription.

This classification tree model enabled explaining 93.50% of the total variance.

In this analysis, it is important to highlight that from the total PHC staff analyzed only 28.6% want to collaborate in exercise prescription with all health and exercise professionals offered in the multiple-choice questionnaire (physicians, nurses, psychologists, physiotherapists, nutritionists, sports medicine physicians, sports scientists, and schoolteachers).

In the tree analysis process III, for the (Yes/No) PA promotion collaboration with sports scientist's predictor variable the results showed 7 nodes defined by the classification tree analysis (Fig. 3).

Level 1 (root node) is PA promotion collaboration with sports physicians by the PHC staff analyzed (node 1: 55.00%), and the non-collaborators (node 2: 45.00%), showing significant differences with predictor variable (p<.001).

At level 2, there were significant differences by health profession (Nurses and GPs) and predictor variable (p<.001). In a first way, 22.2% of GPs (node 5) and 22.8% of nurses (node 6) do not want to collaborate with Sports Physicians and Sports Scientists under a multidisciplinary PAP approach. Furthermore, in the other way of this second level of the tree analysis, there were significant differences in PA promotion collaboration with all health professionals with the predictor variable (p<.001), considering low the collaboration with sports physicians and sports scientists under a multidisciplinary PAP approach (node 3; 26.50%).

This classification tree model enabled explaining 78.00% of the total variance.

In this analysis, it is important to highlight that from the total PHC staff analyzed 39.9% do not want to collaborate with Sports Scientists in PA promotion.

In the tree analysis process IV, for the stage of change of PHC staff for PA promotion predictor variable, according to a 0–4 Likert scale. The results showed 7 nodes defined by the classification tree analysis (Fig. 4).

Level 1 (root node) is PA promotion knowledge by The PCH responders, with a high level of PA promotion knowledge shown for them in the tree analysis (node 2: 70.90%; n=428), and significant differences with the predictor variable (p<.001).

At level 2, there were significant differences in the physically active self-perception and predictor variable (p<.01). With a high level of positive physically active self-perception by the PCH staff (node 3: 60.60%).

At level 3, there were significant differences by PA promotion collaboration with sports scientists and the predictor variable (p<.01). In this way, to the predictor variable and the high levels of PCH staff promoting PAP at this moment and all the previously mentioned independent variables interacting in the tree analysis model, is low the percentage of PHC staff wanting a PAP implementation under a multidisciplinary approach, considering sports scientists (node 5; 38.60%; yes n=233).

This classification tree model enabled explaining 29.10% (node 1), 10.30% (node 4), 38.60% (node 5) and 22.00% (node 6) of the total variance.

In this analysis, it is important to highlight that from the 604 PCH staff analyzed, there are a total of 233 that have maintained PAP for at least 6 months, they were self-considered active and with enough PAP knowledge, however, they want to collaborate with Sports Scientists in exercise prescription.

DiscussionThe analysis of PAP self-perception of two of the most important PHC providers, nurses, and GPs, done in the Autonomous Region of Madrid has shown more than 99% agreement with the exercise and PA health-related preventive benefits. This survey-cohort study showed similar results that Christina Bock et al., offered in a German physician survey in 2012, where almost all physicians considered that PA promotion was part of their duties.21 However, is worrying the fact that 25 and 37% of nurses and GPs, respectively, do not always consider PA health-related benefits good for adult patients of both sexes. A lack of knowledge and training to provide PAP counseling,22,23 and also the lack of skills around behavior change techniques to motivate their patients had been one of the most common barriers to HC staff in the scientific literature.21,24 These aforementioned results of our responders could affect a clear disconnect between the exercise health-related scientific fact and the “theory-practice-gap” of exercise prescription in Health-Care Settings such as has been previously shown by Kennedy et al. for PAP implementation.25 Furthermore, data published in the literature indicates that only around one-third of physicians are using PAP counseling.12 However, these results are lower when patients are asked.17 In contrast, the 81.5% PHC physicians analyzed in our study showed that they maintain the PAP counseling with their patients for more than 6 months. This result contrast with lower exercise prescription levels shown by other authors.26,27 However, our data demonstrate a better frequency of PAP counseling than previous reports of PHC GPs not related to the field of sports medicine,28 and it is well-known that adherence to PAP is a complex and multidimensional phenomenon.29 In this sense, according to the tree analysis process I, the results showed that PHC staff without PA guidelines knowledge and positive attitude to collaborate with nurses in PA promotion are more for the female sex. Besides, in our tree analysis process IV, for the stage of change of PHC staff for PA promotion predictor variable, the results showed that there are significant differences between PCH responders with high level of PA promotion knowledge, positive physically active self-perception and willing to collaborate with sports scientists about PA promotion.

In this sense, physically active behavior shown by PHC staff could affect a future PAP implementation and influence PA promotion for their patients such as has been indicated in the scientific literature.30 But the data shown by the respondents could be not reliable because most of them did not know PA guidelines to be considered physically active or not. In this sense, similar results were offered by PHC staff in Australia in the cohort survey study done by Freene et al.31 Although, the current WHO PA guidelines should be known and properly used by nurses and GPs working in health services providing advice and guidance in PHC Settings.2 The WHO has called for action to integrate physical activity promotion in different context such as schools or healthcare Settings. Furthermore, currently has been established eleven competencies for health professionals, which could serve as a reference to create a culture of advocacy for movement behavior change across all health disciplines,32 with possible transference to exercise professionals, among others.

In addition, PHC professionals were more confident in the self-perception knowledge to promote PA than to prescribe exercise. According to a recent study published by Kennedy et al., the attitude of Health-Care staff to prescribe exercise is considered a barrier to change at a professional stage for PAP implementation.33 However, both assume PAP leadership roles as a potential facilitator for the future PAP implementation in PHC Settings. Otherwise, both are interested in enhancing the PAP training skills by training courses in concordance with the necessities shown in other studies.22,23,30 In this sense, the lack of self-confident behavior in exercise prescriptions could be associated with the lack of exercise training knowledge. A mean of 70.4% indicated no exercise training background with a mean of less than one exercise prescription course for all PHC professionals during most of the 23 years of mean PHC career experience for the sample analyzed.

Furthermore, the results of this study with more than half GPs and nurses willing to collaborate with sports scientists and public sports centers contrast with the results obtained in the study of Pojednic et al., with less than half of physicians surveyed, concerned with certified trainers or specific outstanding teachers for PAP implementation. In this way, in our study, less than half of the responders were willing to collaborate with wellness and private gym centers in a similar way that is shown in the scientific literature.34 However, the good predisposition in the collaboration with some sport facilities in our study is not only for the physicians of Spain. It has been shown previously in a German survey cohort study developed by Bock et al.21

Additionally, all the PHC respondents showed willing to collaborate with all health professional staff proposed, having the physician's 98.7% (OR: 1.987) more than probability to collaborate with all of them than nurses. Besides, almost all PHC professionals agreed to the collaboration with other community resources to enhance PAP in the PHC System, even although, both groups were interested in creating a PAP networking with other professionals and institutions with the aim to increase efficiency to prevent NCDs, according to the Exercise is Medicine initiative.14 Despite of many studies have identified the lack of exercise resources such as lack of supervised exercise programs and qualified staff or exercise experts as a part of the multidisciplinary core care team as PAP implementation barriers.24,34

As limitation of this study, we would like to say that results obtained from this survey study could be biased by the sampling procedure performed, because it was not possible to guarantee a representative sample of the Madrid PHC System, despite the online questionnaires being sent by e-mail to all GPs and nurses of the Autonomous Region of Madrid. However, the low response rate of responders could be related to the PHC staff being more able or in favor of PAP.

ConclusionsGPs and nurses are conscious of the exercise and PA health-related benefits despite the lack of resources and self-perception barriers observed to implement PAP in PHC Settings. Collaboration with other health personnel, exercise professionals, and community resources are the main barriers observed in both PHC professionals.

According to these results, it is necessary to improve the exercise knowledge and training of GPs and nurses, design a procedure, and identify the stage of change of PHC staff to PA promotion who should assume a leadership role working with other professionals and community resources under a multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary approach.

- •

Physical inactivity and sedentary levels are well-known predictors of non-communicable diseases and key risk factors for premature death.

- •

Exercise prescriptions could be a coadjutant treatment at least on 26 non-communicable diseases.

- •

There is a clear disconnect between the exercise health-related benefits and the “theory-practice gap” of exercise prescription in Health-Care Settings.

- •

This is the first study analysing the Physical Activity on Prescription self-perception of Primary Health-Care staff under a classification tree analysis.

- •

These data and this design model could be considered to effectively implement Physical Activity on Prescription in any Primary Health-Care System.

- •

Under a socioecological model approach, the analysis of interpersonal, organizational and community resources as we analyze in this study are key for an efficient Physical Activity on Prescription implementation and to resolve the “theory-practice gap” of exercise prescription in Primary Health-Care Settings.

This work was supported by the funds of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III through CIBEROBN CB12/03/30038 [2015-2019], which is co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund, and the Programa Unión Europea-NextGenerationEU y el Ministerio de Universidades [2022].

Ethical considerationsThe study was performed according to the principles established with the Declaration of Helsinki 1964 and further amendments and other national regulations for research projects involving human participants: Protection of Personal Data, Law 15/1999 of 13 December on the Protection of Personal Data provided in the current legislation (Royal Decree 1720/2007 of 21 December). The protocol study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the “Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón” and the Central Commission for research of the Region of Madrid with the protocol code: 42/17; ID:RP1811600040 (date: 13/12/2017).

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

We would like to thank to all PHC GPs and nurses of Madrid who gave their time and shared their self-perception barriers and facilitators to implement PAP at PHC settings on behalf of Madrid Health-Care System.