Introduction

Immigration in Spain has increased in the last decade, along with the consequent problems of adaptation for both recent arrivals and long-time inhabitants. These problems are especially notable when the two groups are from different cultures.

Health professionals have had to adapt, with time, to this situation. One of the most frequent concerns among physicians and nurses in primary care is the quality of care provided to these collectives. Immigrant groups generate large numbers of visits which are marked by language and culture barriers that make communication and diagnosis difficult. This in turn can lead to the feeling that visits for psychiatric problems are more frequent than in the autochthonous population. Immigration is known to be a risk factor for health problems,1 especially psychiatric disorders. Immigration can thus be seen as a kind of mourning2 for the loss not only of ones own language and culture, but also for ones family, homeland and social status. Many variables which go into the creation of this mourning influence the degree of success of immigration. When the process of mourning and recovery fails, mental disorders often result.3

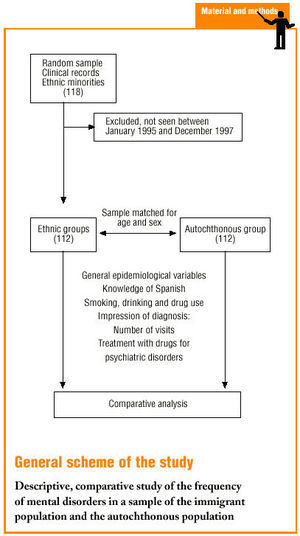

On the basis of this hypothesis we designed a study to determine whether there were differences in the frequency of mental disorders between the autochthonous population and the population belonging to different ethnic groups. Information was obtained from the medical records of out-patient visits to local health centers. We also investigated some epidemiological data to identify the characteristics of members of ethnic groups, compare them with the autochthonous population and evaluate the accuracy of recording of epidemiological data in these two population groups.

Material and methods

The target population for this study comprised patients served by the health center of the Raval Sud Basic Health Area, administered by the Drassanes Primary Care Center under the auspices of the City of Barcelona Subdivision of the Catalonian Health Institute. The center is located in the Ciutat Vella district of Barcelona, and as of May 2001 housed a total of 28 677 individual medical records. The population served by this center is characterized by its low socioeconomic level and high prevalence of marginalization. According to the 1996 census, the immigration rate in the Ciutat Vella district was 5%; this rate had risen to 20% by May 2001. The rate of immigration as deduced from the numbers of patient records at the study center increased from 5% to 14.1%; and the risk factor of belonging to an ethnic minority was noted in 4041 records.

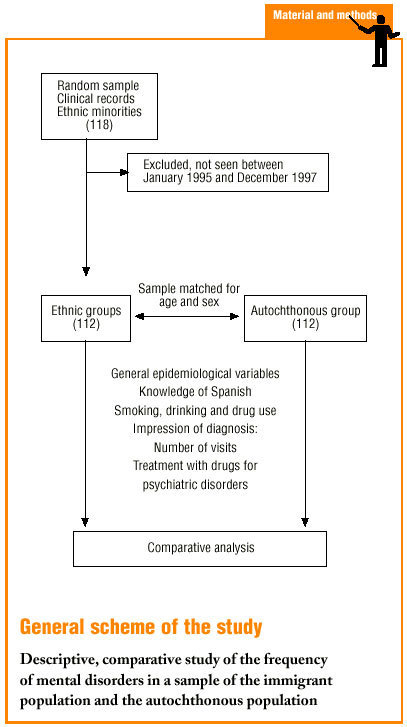

A descriptive, cross-sectional study was designed with a sample of 118 patients (minimum criteria p=1-p=0.5, Z=1.96, e=0.09). Medical records were chosen randomly from the total of all records that noted ethnic minority as a risk factor. Form this sample we included in the study all immigrant members of an ethnic minority who visited their doctor for any reason between January 1995 and December 1997 (the 3-year period prior to data collection). We excluded 6 patients who did not fulfil these criteria. The final sample consisted of 112 patients who were paired for age and sex with a control group consisting of 112 patients belonging to the autochthonous population. The medical record of each patient was reviewed and a data collection sheet was used to record information on general epidemiological variables such as age, sex, year of first visit to the health center, year of immigration and administrative status. In addition we recorded variables related with mental disorders in immigrants such as country of origin or ethnic group, reason for emigrating, marital status, persons in the household, and employment status. A third group of variables was related with communication during the clinical interview, ie, knowledge of Spanish and educational level. We also recorded information about smoking habit, alcohol consumption (considered excessive at >40 g/day in men and >20 g/day in women) and drug use (parenteral and other drugs).

With regard to information about mental health, we reviewed the records of the visits to the health center during the study period to record the following impressions of the diagnosis: anxiety, depression, somatization disorder, psychosis, personality disorder or other neurosis as judged by the physician who saw the patient. We also noted the number of visits to the center for each type of diagnosis, and whether the diagnosis had been made previously in the immigrant´s country of origin. The drugs used to treat psychiatric disorders and the number of visits for any reason during the 3-year study period were recorded to evaluate patterns of usage of the health center.

Statistical studies consisted of descriptive analysis and chi-squared tests.

Results

The final sample consisted of 112 immigrant patients for whom ethnic minority was recorded as a risk factor, and who had visited the center at least once during the study period. Mean age was 39±14 years, and 52.7% were males. Distribution according to country of origin (table 1) was 36.6% (41) from the Maghreb region, and 23.2% (26) from the Hindustan region (Bangladesh, Pakistan and Afghanistan). The reason for emigrating was not recorded for 79.5% of the patients; for the remaining patients the most frequent reasons were economic (45.4%; n=10; 95% CI, 24.6-66.2) and family reunification (41%; n=9; CI 20.3-61.4). The epidemiological data for immigrant and autochthonous patients are compared in table 2. Employment status was not stated for 26.8% of the immigrant patients and 21.4% of the autochthonous patients. Of those for whom this information was recorded, 53.7% of the immigrant patients and 44.3% of the autochthonous patients were employed. Of those who were unemployed, only 9% of the former (n=3; CI, -0.7 to -18.9) and 20% of the latter (n=8; CI, 7.6-32.4) were receiving unemployment benefits. No information on marital status was given for 30.4% of the patients in both groups, and information on the number of persons in the household was missing for 31.3% of the former group, and for 28.6% of the latter. Educational level was not given in 72.1% of the records for immigrant patients, and in 58% of the records for autochthonous patients.

No information on knowledge of Spanish was found in 51.8% of the records for immigrant patients. Of the rest of the records, 11.1% (n=6; CI, 2.7-19.4) recorded no knowledge, 13% (n=7; CI, 4.0-21.9) noted the patient understood but did not speak Spanish, 33.3% (n=18; CI, 20.7-45.9) noted that the patient spoke Spanish, and 42.6% (n=23; CI, 29.4-55.7) were able to write Spanish. Overall, at least 43% (n=48; CI, 33.6-52.0) of this sample posed no linguistic problems for the medical staff, although it should be noted that 14% of the members of the immigrant group were from Spanish-speaking countries.

Table 2 shows that the prevalence of smoking, alcohol abuse and parenteral or other drug use was significantly greater in the immigrant group.

Our comparison of mental disorders in immigrant and autochthonous control patients (table 3) failed to detect significant differences between groups for any of the diagnoses, although there was a trend toward higher percentages in the former group for depression (15.2% versus 13.4%) and somatization disorder (10.7% versus 6.3%). In contrast, a diagnosis of anxiety was more frequent in the control group (26.8% versus 17.9%), as was personality disorder (3.6% versus 0%) and psychosis (5.4% versus 0%). The frequencies of other neuroses were the same in both groups.

For all patients with a diagnosis of mental disorder, we sought information about the treatment prescribed (table 4). Prescriptions were given for 19.8% (n=22; CI, 12.4-27.2) of the patients in the immigrant group and for 32.1% (n=36; CI, 23.4-40.7) of those in the control group. There were no significant differences in the types of treatment, although benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants were prescribed more frequently in the immigrant group.

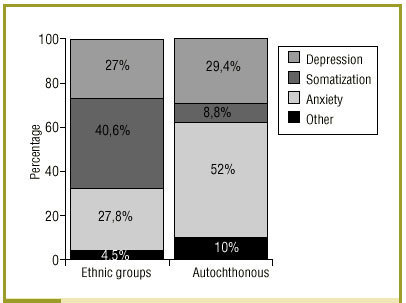

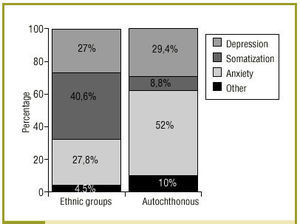

During the study period the immigrant group made a total (for any reason) of 1017 visits to the center, of which 13% (n=132; CI, 10.9-15.0) were for mental disorders. The group of autochthonous patients made a total of 1138 visits, of which 17.9% (n=204; CI, 15.7-20.1) were for mental disorders. When we examined all visits for mental disorders (fig. 1), we found that in the immigrant group the predominant diagnosis was somatization (40.6%), followed by anxiety (27.8%) and depression (27%). Other neuroses and personality disorder each accounted for 1.5% of the visits. In the control group, the most frequent diagnosis was anxiety (52%), followed by depression (29.4%) and somatization (8.8%). Other neuroses each accounted for 1.5% of the diagnoses, personality disorder for 1%, and psychosis for 7.4%.

Fig 1:Comparison of the numbers of visits for mental disorders in patients who belonged to ethnic minorities and to the autochthonous population.

Discussion

The sample of immigrants we studied represents a young population in which males were slightly more numerous; most members of this population are from Islamic countries (the Maghreb region, Pakistan, Afghanistan, India and Bangladesh). Most immigrated for economic reasons or to join other members of their family. Most are married, although not all live with their partner.

Only 53.7% of the immigrant patients we studied were employed at the time of the study. The high unemployment rate was also seen in the autochthonous population (44.3% employed at the time of the study); these figures may be attributable to the low sociocultural level and marginalization of most of the population living in the study area. The only difference between immigrant and autochthonous patients was the higher percentage of immigrants who were working without a written contract, and the lower number of unemployed persons who were receiving benefits in the immigrant group. These findings may be related with the precarious employment status of immigrants and the difficulties they have obtaining unemployment benefits.

The educational level was generally low in the population of patients who belong to ethnic minorities; this may reflect the fact the persons who emigrate for economic reasons (as in our sample) have often received little formal education. With regard to knowledge of Spanish, although only 14% of the members of the immigrant group were from countries where Spanish is used, we found that 43% of the sample were able to at least understand the language. In other words, medical professionals should not, in theory, have had language difficulties with these patients.

We found large differences between the two populations in smoking and drinking patterns and parenteral drug use--which is highly prevalent in the study area. The low prevalence of smoking, drinking and drug use the group of ethnic minorities is readily attributable to the religious beliefs of the Muslim majority.

With regard to the main hypothesis of the study, we did not find a larger percentage of mental disorders in the immigrant population. We did find a trend for this population to present more somatization disorders, as shown by the high number of visits for this motive, and the greater frequency of depression. It should be recalled, however, that these diagnoses were recorded only as impressions of the diagnosis or suggested diagnoses that the physicians noted in the patient´s record during the interview. Our sample size may have been too small to confirm our hypothesis; moreover, this was a descriptive study that collected data for a limited period, not a prevalence study. These considerations, together with the low frequency with which certain data were recorded in the charts, may have led to the introduction of biases in the study.

Nonetheless, our results are similar to those of other studies such as that published by the Servicio de Atención Psicopatológica y Psicosocial a Inmigrantes y Refugiados (SAPPIR) (Immigrant and Refugee Psychopathology and Psychosocial Care Service) of Barcelona.4 This report found that patients visited their health service most often for somatoform and depressive symptoms, that the main group of users comprised immigrants from Pakistan, and that mean age of the consulters was 35 years. As noted earlier, the reference population with which the ethnic population was compared was characterized by its low social, cultural and economic level and high rate of marginalization. These features most likely account for the high prevalence of acute organic and chronic communicable and non-communicable diseases, as well as of psychiatric disorders and the use of drugs for such disorders. This may be one reason why we failed to find significant differences in the prevalence of mental disorders between the two populations. Another reason may be that, because of the cultural and linguistic differences, the population of ethnic groups described psychiatric symptoms in a manner that differed markedly from the hallmark symptoms that lead practitioners to establish a psychiatric diagnosis.5-8 This would invalidate existing questionnaires for psychiatric diagnoses,9 and would also explain why many visits are interpreted by physicians to indicate somatic symptoms that do not receive a more specific diagnosis or treatment. This would lead to underdiagnosis of mental disorders, and to undertreatment resulting from a misunderstanding or from the patient´s adaptation to the new cultural setting and subsequent decision to seek no further care. A similar explanation was offered by Farooq et al.,10 who compared Caucasian and Asiatic populations in their study of psychosomatic disorders, and by other authors11,12 who reported different forms of expression of depression and different treatments in ethnic groups.

Perhaps the most relevant finding of our study is the frequent lack of information in the medical record--especially in the records for immigrant patients--regarding most of the epidemiological variables we investigated. For important variables such as country of origin, this information was missing in 13.4% of the charts. Likewise, the percentages of records in which information on specific variables was not found were 79.5% for reason for emigrating, 30.4% for marital status, 51.5% for number of persons in the household, 72.1% for educational level, and 51.8% for knowledge of Spanish. The fact that such information was missing much more frequently in the records for immigrant patients may be attributable, again, to communication problems. Such problems, together with the pressures resulting from the patient overload in the health care district that comprised our study area, may have led to a decline in the quality of care for these population subgroups, whose members require more specialized attention, or at the least, the availability of an interpreter or mediator. Studies have shown that interpreters and mediators significantly improve communication with health professionals.13,14

To promote measures aimed at improving these areas, and on the basis of the results of our study, we have developed an easy-to-use epidemiological data collection sheet which has become part of the clinical records of all patients belonging to an ethnic minority. The data sheet allows health professionals to collect all the information needed to identify the basic characteristics of different ethnic groups--which comprise an increasing proportion of the patients served by the study area--and which can be used to design future interventions.

Correspondence: J. Pertiñez Mena. ABS Raval Sud, Institut Català de la Salut, Avda. Drassanes 17-21 6.a planta, 08001 Barcelona, Spain. Manuscript accepted for publication 23th July 2001.