To assess the effectiveness of a training program for Primary Care (PC) professionals developed to increase knowledge, attitudes, and skills for managing patients with risky alcohol use and in the motivational interview.

DesignMulticenter, two-arm parallel, randomized, open-label controlled clinical trial.

SettingPC of the Andalusian Health Service.

ParticipantsThe study was completed by 80 healthcare professionals from 31 PC centers.

InterventionsIn both experimental and control groups, a workshop on managing patients with risky alcohol consumption and the resolution of two videotaped clinical cases with standardized patients were conducted. The experimental group attended a workshop on motivational interviewing.

Main measurementsKnowledge about managing risky alcohol use, clinical performance in patients with this health problem, and assessment of the motivational interview.

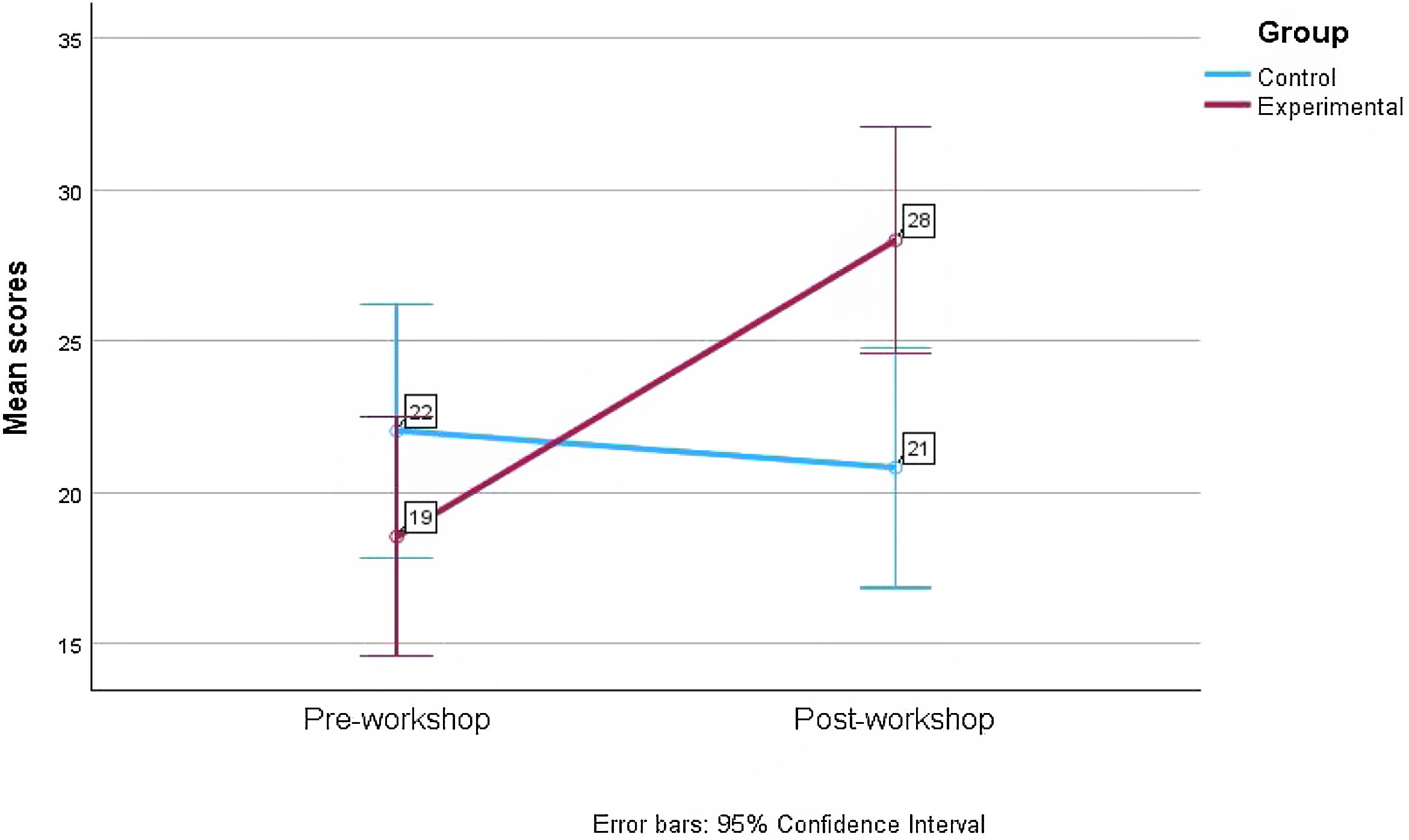

ResultsMean age was 39.50±13.06 – SD – (95% CI: 36.59–42.41); 71.3% (95% CI: 61.1–80.9%) were women. The average score of both groups in the knowledge questionnaire before the training program was 15.10±4.66, becoming 21.99±3.93 points after the training (95% CI: 5.70–7.92; p<0.001). The experimental group showed an average score of 18.53±13.23 before the intervention with the motivational interview and 28.33±11.86 after this intervention (p=0.002). In contrast, no significant variation was found in the score of the control group.

ConclusionsA training program aimed at PC professionals designed to increase knowledge on how to manage risky alcohol use and acquire communication skills in motivational interviewing is effective.

Evaluar la efectividad de un programa de formación para profesionales de Atención Primaria (AP) para incrementar conocimientos, actitudes y habilidades en el manejo de pacientes con consumo de riesgo de alcohol y en la entrevista motivacional.

DiseñoEnsayo clínico controlado, abierto, aleatorizado, multicéntrico, paralelo de dos brazos.

EmplazamientoCentros de AP del Servicio Andaluz de Salud.

ParticipantesFue completado por 80 profesionales sanitarios de 31 centros.

IntervencionesEn el grupo experimental y en el control se realizó un taller de manejo de pacientes con consumo de riesgo de alcohol y la resolución de dos casos clínicos videograbados con pacientes estandarizados. El grupo experimental asistió a un taller sobre entrevista motivacional.

Mediciones principalesConocimiento sobre el manejo del consumo de riesgo de alcohol, desempeño clínico en pacientes con este problema de salud y valoración de la entrevista motivacional.

ResultadosLa edad media fue 39.50±13,06 -DE- (IC 95%: 36,59-42,41); El 71,3% (IC 95%: 61,1%-80,9%) eran mujeres. La puntuación media en el cuestionario de conocimientos antes del programa de formación fue de 15,10±4,66, siendo 21,99±3,93 puntos después del entrenamiento (IC 95%:5,70-7,92; p<0,001). La puntuación promedio del grupo experimental antes de la intervención con la entrevista motivacional era de 18,53±13,23 y después de 28,33±11,86 (p=0,002). No se encontró variación significativa en la puntuación del grupo control.

ConclusionesUn programa de formación para profesionales de AP, para incrementar el conocimiento sobre cómo gestionar el consumo de riesgo de alcohol y adquirir habilidades comunicativas en la entrevista motivacional es efectivo.

Alcohol is the most consumed psychoactive drug in Spain.1 During 2010–2017, there were 15,489 deaths per year attributable to alcohol.2 About 15% of patients attending Primary Care (PC) consultations present risky alcohol use.3 Given the magnitude of this problem, health professionals must acquire the knowledge and skills to address it effectively. However, recent studies reveal a specific lack of performance and management of patients with excessive alcohol consumption by PC professionals.4,5 It has been found that professionals with a higher level of training in managing alcohol consumption were more confident in facing the related problems in their patients and used more appropriate strategies for patient management.6 A systematic review reported that the main reasons for not addressing the patient at risk are lack of time, low self-confidence about their ability to perform screening tests and provide brief advice, and lack of training.5

Given the poor training in addressing the risky alcohol use among PC professionals,7 it is evident the relevance of implementing training programs specifically designed for them to acquire the appropriate knowledge to address this health problem; evaluating the results of these activities is also convenient. A systematic review8 concluded that the implementation of training programs focused on improving the management of patients with risky alcohol use constitutes an effective strategy, encouraging population screening and the use of the most appropriate intervention techniques, such as those based on motivational interviewing (MI). MI is cost-effective in treating toxic substance use, producing the same effects as specific treatments, and requiring less time and resources than these to achieve similar results.9

A study reported that a significant improvement was obtained in knowledge about managing alcohol consumption and MI skills10 through a training activity specifically designed for this purpose. Another study found that this type of training effectively improved MI skills, allowing the implementation of this communicative model in PC consultations.11

Despite the evidence, it is still necessary to conduct more studies to corroborate the conclusions obtained so far and provide more consistency. With this purpose, the main objective of the present study was to assess whether a training program specifically designed for PC professionals, whose objective was to increase the knowledge, attitudes, and skills for managing patients with risky alcohol use and in MI, is effective.

Material and methodsDesignThis study is a multicenter, two-arm parallel, randomized, open-label controlled trial.

LocationPC of the Andalusian Health Service.

ParticipantsInclusion criteria: PC professionals who expressed their willingness to enroll in the training program and their explicit commitment to get involved as clinical researchers in a subsequent controlled clinical trial (CCT) aimed at demonstrating that MI is effective in addressing excessive alcohol consumption in patients attended in PC consulting rooms (ALCO-AP20 study).12 Exclusion criteria: To have previous competencies and skills in MI or to refuse to participate in the study.

The population scope of the study was the health care professionals recruited through the Multiprofessional Teaching Unit of Family and Community Care of the Cordoba and Guadalquivir Health District, who were invited to participate.

Sample size and randomizationBased on a previous study,10 assuming an alpha risk of 0.05 and a beta risk of 0.2, it would be necessary to include 81 subjects, assuming that the initial proportion of knowledge that was considered “acceptable” (80% of correct questions in both groups) was 35% and after the training intervention, at least 60%.

The participating healthcare professionals were randomly assigned to the experimental group (EG) or the control group (CG), with the program EPIDAT 4.1.

InterventionsThe 16-h training program was accredited by the Andalusian Health Quality Agency (ACSA, File 514/20,219) and consisted of the following activities:

Training interventions common to both groups:

- -

Workshop on management of patients with risky alcohol use: Its objective is to provide knowledge, attitudes, and specific skills on the management of patients with excessive alcohol consumption.

- -

Resolution of two practical, fictitious clinical cases with standardized patients. Before and after the training activities, the participants were videotaped performing consultations with two actors previously trained, simulating to be patients with suspected risky alcohol use. The two scripts of the interventions and the evaluations were conducted by two experts in alcohol consumption management and MI. For the evaluation, the experts provided feedback to each participant, using the Motivational Interview Rating Scale (EVEM).13

MI Workshop:

- -

The EG members also received specific brief training in MI.14 MI is a collaborative, patient-centered conversation style that boosts motivation, self-efficacy, and commitment to behavior change.15 Participants of the CG were trained in the usual health advice based on the information model, which consists of trying to persuade the patient to change behavior.16

Independent variables: Through an online questionnaire, sociodemographic and employment data were collected, such as the profession, contractual relationship with the health system, time worked in PC, and information about their usual performance in a patient with excessive alcohol consumption.

Dependent variables: Level of knowledge on the management of risky alcohol use. Through a self-administered questionnaire consisting of 44 test questions, different aspects related to alcohol consumption were measured: (a) Importance and magnitude of the problem, (b) Concepts related to risky alcohol use, management of this problem in PC consultations, (c) Impact of drinking on families, and (d) Knowledge about its pharmacological treatment. These researchers considered the recommendations of the PAPPS.17

Evaluation of the standardized clinical interview: The EVEM13 was used to evaluate MI in the communicational health care professional–patient relationship in PC settings. EVEM comprises 14 items with a maximum total score of 56 points. After the standardized consultations, each participant received personalized training feedback on their 2 video recordings of the consultations by two experts in healthcare communication, after which they completed the EVEM questionnaire.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis was performed. It was followed by an inferential analysis, with the estimation of the confidence intervals for 95% safety – 95%CI, and bivariate analysis to verify the differences between group, as well as the relationship between the socio-occupational variables and the level of knowledge of professionals, the performance when addressing the risky alcohol use, or the degree of use of MI, applying for it the tests of the Chi-square, the Student T test or the ANOVA for repeated measures, after checking fit to a normal distribution of the outcome variables, using the Shapiro–Wilk test, otherwise using non-parametric tests, such as the Wilcoxon test. Bilateral contrasts were used (p≤0.05). The statistical program SPSS V.29 was used.

The research project received the authorization of the Management of the Health District Cordoba and Guadalquivir and the approval of the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Reina Sofia Hospital of Cordoba. Informed consent was requested that grants voluntary participation in the study of professionals and patients. The processing of the personal data of the subjects participating in the study was in accordance with the provisions of the European Data Protection Regulation and Organic Law 3/2018 on the Protection of Personal Data and the Guarantee of Digital Rights.

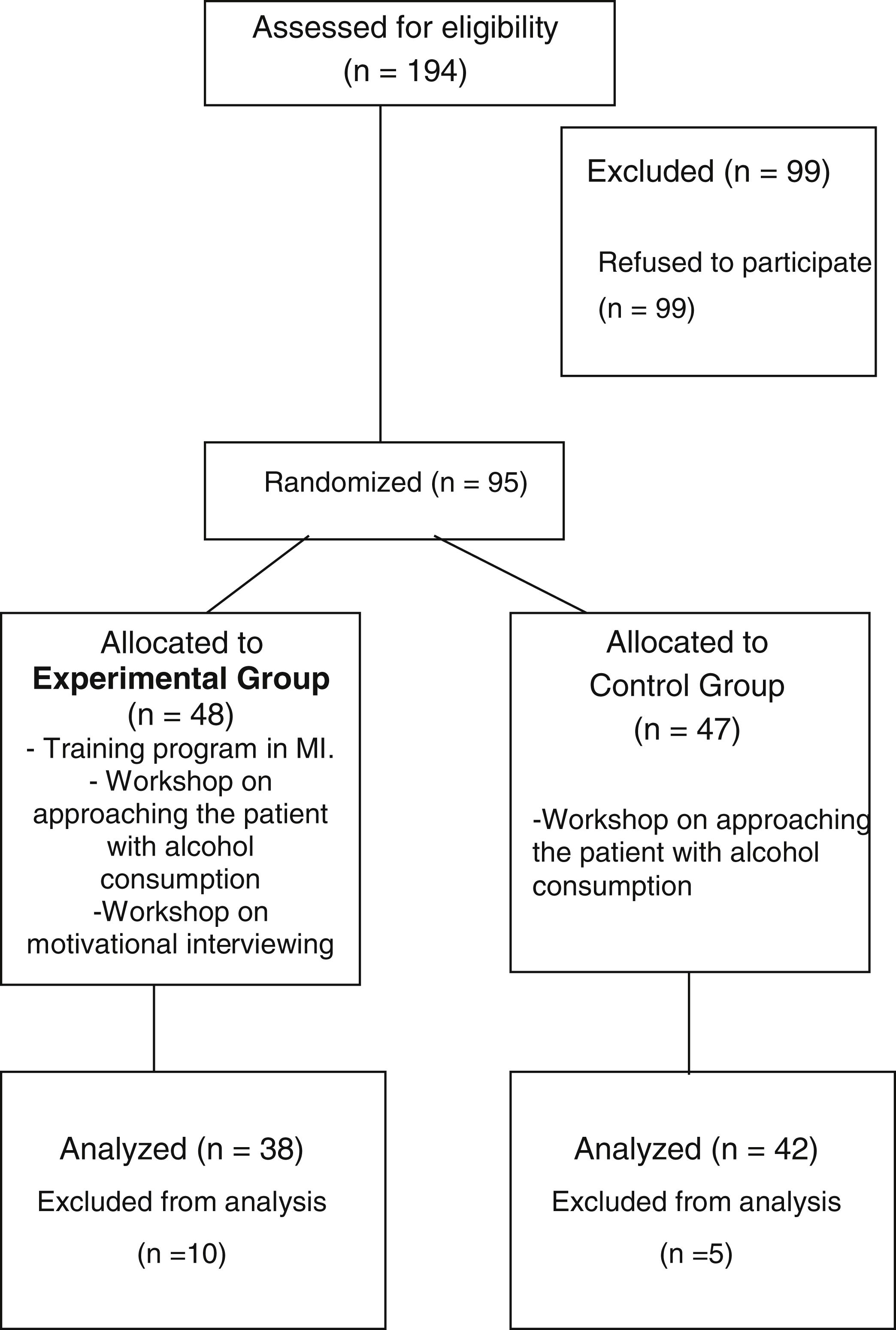

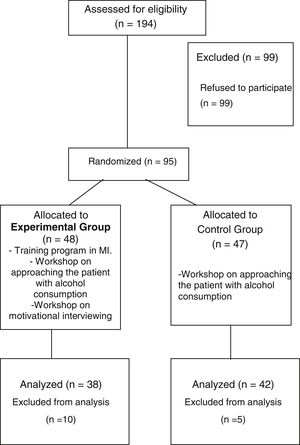

Study flowchart: Consort diagram.

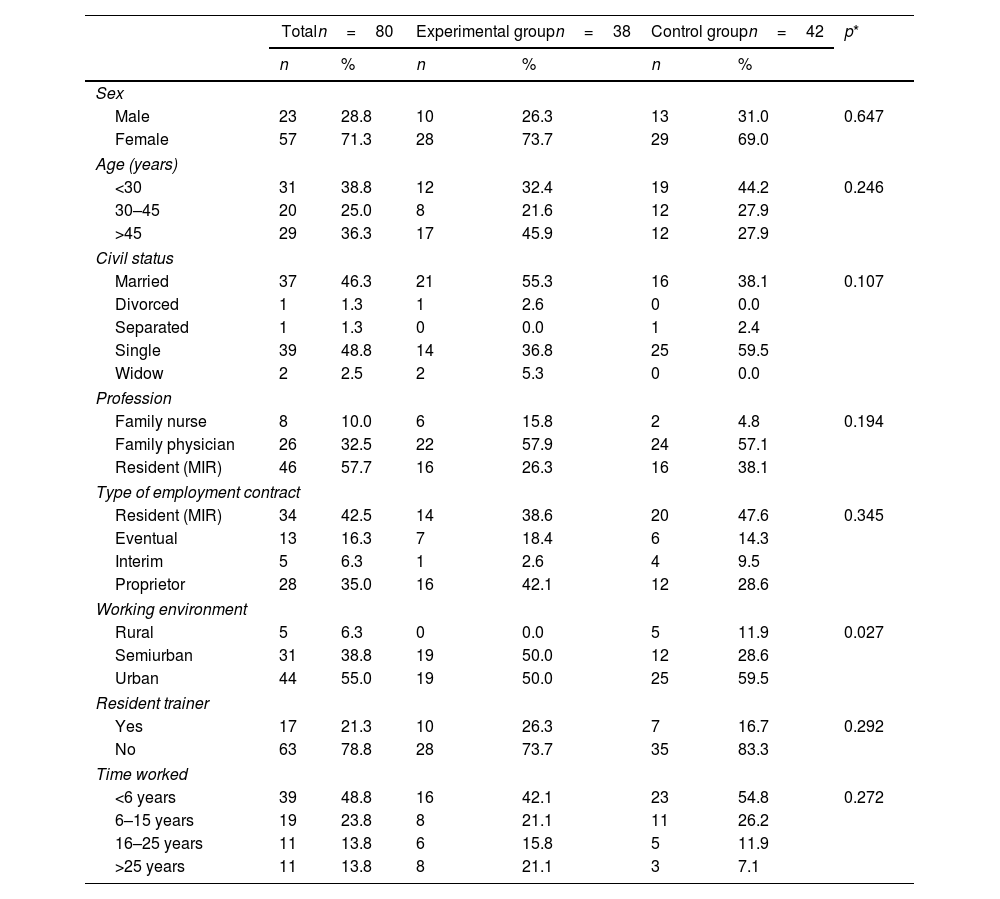

ResultsPhysicians and nurses from PC, tutors of residents (n=74), and family and community medicine or nursing residents (n=120) of the Cordoba-Guadalquivir Health District were invited to participate in the study. A total of 95 professionals agreed to participate, of which 15 were excluded because they did not indicate in the registry the group to which they were assigned. Fig. 1 shows the flow chart for the study. Eighty professionals were assigned to one of the two study groups: 42 subjects to CG (52.5%) and 38 to EG (47.5%). The sociodemographic and occupational characteristics of the participants according to the allocation group are shown in Table 1.

Sociodemographic and employment characteristics of the participants, according to the group.

| Totaln=80 | Experimental groupn=38 | Control groupn=42 | p* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 23 | 28.8 | 10 | 26.3 | 13 | 31.0 | 0.647 |

| Female | 57 | 71.3 | 28 | 73.7 | 29 | 69.0 | |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| <30 | 31 | 38.8 | 12 | 32.4 | 19 | 44.2 | 0.246 |

| 30–45 | 20 | 25.0 | 8 | 21.6 | 12 | 27.9 | |

| >45 | 29 | 36.3 | 17 | 45.9 | 12 | 27.9 | |

| Civil status | |||||||

| Married | 37 | 46.3 | 21 | 55.3 | 16 | 38.1 | 0.107 |

| Divorced | 1 | 1.3 | 1 | 2.6 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Separated | 1 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.4 | |

| Single | 39 | 48.8 | 14 | 36.8 | 25 | 59.5 | |

| Widow | 2 | 2.5 | 2 | 5.3 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Profession | |||||||

| Family nurse | 8 | 10.0 | 6 | 15.8 | 2 | 4.8 | 0.194 |

| Family physician | 26 | 32.5 | 22 | 57.9 | 24 | 57.1 | |

| Resident (MIR) | 46 | 57.7 | 16 | 26.3 | 16 | 38.1 | |

| Type of employment contract | |||||||

| Resident (MIR) | 34 | 42.5 | 14 | 38.6 | 20 | 47.6 | 0.345 |

| Eventual | 13 | 16.3 | 7 | 18.4 | 6 | 14.3 | |

| Interim | 5 | 6.3 | 1 | 2.6 | 4 | 9.5 | |

| Proprietor | 28 | 35.0 | 16 | 42.1 | 12 | 28.6 | |

| Working environment | |||||||

| Rural | 5 | 6.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 11.9 | 0.027 |

| Semiurban | 31 | 38.8 | 19 | 50.0 | 12 | 28.6 | |

| Urban | 44 | 55.0 | 19 | 50.0 | 25 | 59.5 | |

| Resident trainer | |||||||

| Yes | 17 | 21.3 | 10 | 26.3 | 7 | 16.7 | 0.292 |

| No | 63 | 78.8 | 28 | 73.7 | 35 | 83.3 | |

| Time worked | |||||||

| <6 years | 39 | 48.8 | 16 | 42.1 | 23 | 54.8 | 0.272 |

| 6–15 years | 19 | 23.8 | 8 | 21.1 | 11 | 26.2 | |

| 16–25 years | 11 | 13.8 | 6 | 15.8 | 5 | 11.9 | |

| >25 years | 11 | 13.8 | 8 | 21.1 | 3 | 7.1 | |

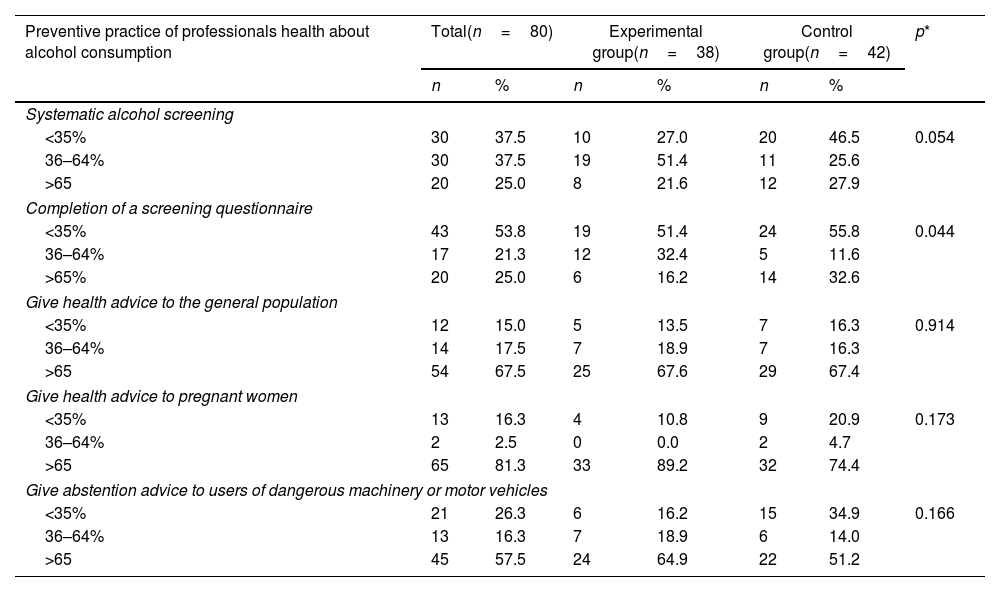

A total of 37.5% of health professionals conduct a systematic examination of alcohol consumption in 35–64% of the time, whereas 25% conduct it in more than 65% of the time. Furthermore, 53.4% reported they administer a screening questionnaire to their patients in the case of suspected alcohol dependence or risky alcohol use on less than 35% of the occasions. A total of 67.5% of professionals reported providing health advice to decrease alcohol intake in the general population more than 65% of the time, 81.3% in pregnant women, and 57.5% in the case of users of dangerous machinery or motor vehicles. Table 2 shows the results for the issues in this section according to the allocation group.

Preventive practice of health professionals regarding alcohol consumption according to assignment group.

| Preventive practice of professionals health about alcohol consumption | Total(n=80) | Experimental group(n=38) | Control group(n=42) | p* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Systematic alcohol screening | |||||||

| <35% | 30 | 37.5 | 10 | 27.0 | 20 | 46.5 | 0.054 |

| 36–64% | 30 | 37.5 | 19 | 51.4 | 11 | 25.6 | |

| >65 | 20 | 25.0 | 8 | 21.6 | 12 | 27.9 | |

| Completion of a screening questionnaire | |||||||

| <35% | 43 | 53.8 | 19 | 51.4 | 24 | 55.8 | 0.044 |

| 36–64% | 17 | 21.3 | 12 | 32.4 | 5 | 11.6 | |

| >65% | 20 | 25.0 | 6 | 16.2 | 14 | 32.6 | |

| Give health advice to the general population | |||||||

| <35% | 12 | 15.0 | 5 | 13.5 | 7 | 16.3 | 0.914 |

| 36–64% | 14 | 17.5 | 7 | 18.9 | 7 | 16.3 | |

| >65 | 54 | 67.5 | 25 | 67.6 | 29 | 67.4 | |

| Give health advice to pregnant women | |||||||

| <35% | 13 | 16.3 | 4 | 10.8 | 9 | 20.9 | 0.173 |

| 36–64% | 2 | 2.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 4.7 | |

| >65 | 65 | 81.3 | 33 | 89.2 | 32 | 74.4 | |

| Give abstention advice to users of dangerous machinery or motor vehicles | |||||||

| <35% | 21 | 26.3 | 6 | 16.2 | 15 | 34.9 | 0.166 |

| 36–64% | 13 | 16.3 | 7 | 18.9 | 6 | 14.0 | |

| >65 | 45 | 57.5 | 24 | 64.9 | 22 | 51.2 | |

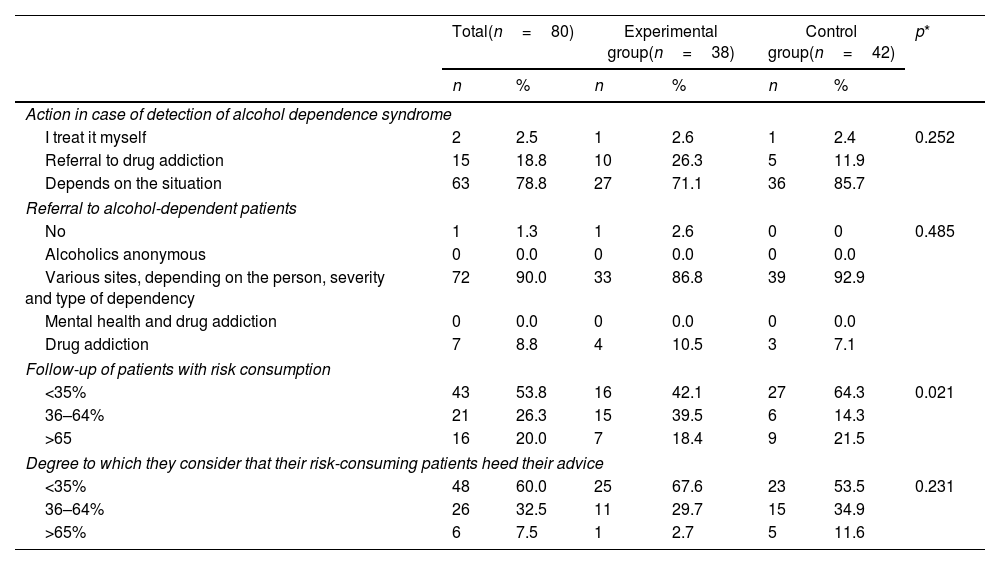

As shown in Table 3, 78.8% (95%CI: 69.8–87.8%) of the professionals reported that their performance in a case of detection of risky consumption depends on the situation, and 90% (95%CI: 83.4–96.6%) refer patients to various sites, depending on the person, severity, and type of dependency. 12.5% (95%CI: 5.3–19.7%) reported following-up the patient with risky use on more than 90% of the occasions.

Approach to the patient with risky consumption of alcohol, according to the assignment group.

| Total(n=80) | Experimental group(n=38) | Control group(n=42) | p* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Action in case of detection of alcohol dependence syndrome | |||||||

| I treat it myself | 2 | 2.5 | 1 | 2.6 | 1 | 2.4 | 0.252 |

| Referral to drug addiction | 15 | 18.8 | 10 | 26.3 | 5 | 11.9 | |

| Depends on the situation | 63 | 78.8 | 27 | 71.1 | 36 | 85.7 | |

| Referral to alcohol-dependent patients | |||||||

| No | 1 | 1.3 | 1 | 2.6 | 0 | 0 | 0.485 |

| Alcoholics anonymous | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Various sites, depending on the person, severity and type of dependency | 72 | 90.0 | 33 | 86.8 | 39 | 92.9 | |

| Mental health and drug addiction | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Drug addiction | 7 | 8.8 | 4 | 10.5 | 3 | 7.1 | |

| Follow-up of patients with risk consumption | |||||||

| <35% | 43 | 53.8 | 16 | 42.1 | 27 | 64.3 | 0.021 |

| 36–64% | 21 | 26.3 | 15 | 39.5 | 6 | 14.3 | |

| >65 | 16 | 20.0 | 7 | 18.4 | 9 | 21.5 | |

| Degree to which they consider that their risk-consuming patients heed their advice | |||||||

| <35% | 48 | 60.0 | 25 | 67.6 | 23 | 53.5 | 0.231 |

| 36–64% | 26 | 32.5 | 11 | 29.7 | 15 | 34.9 | |

| >65% | 6 | 7.5 | 1 | 2.7 | 5 | 11.6 | |

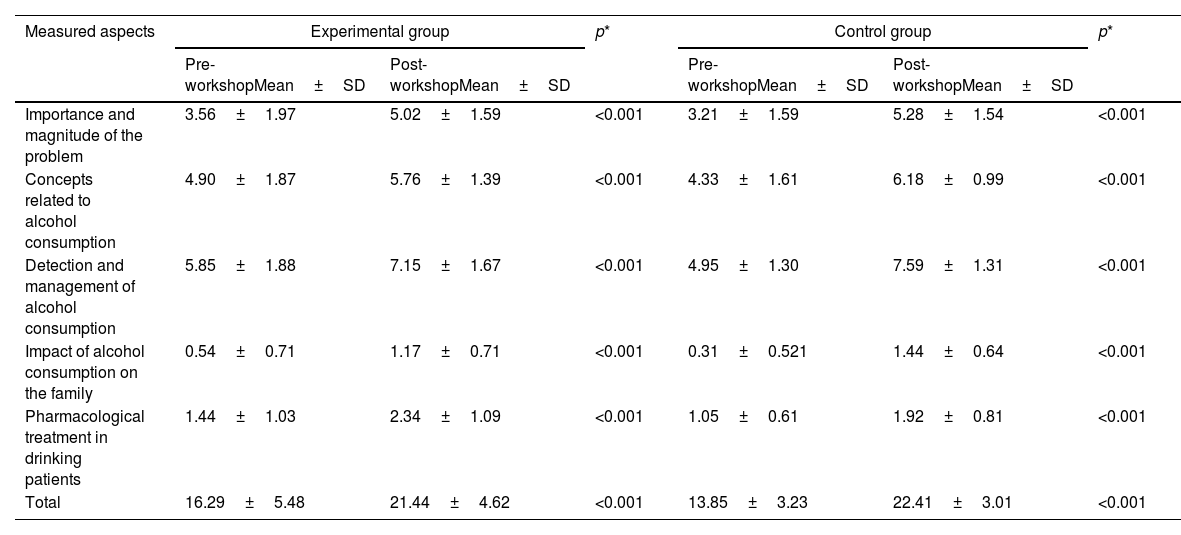

The average score of both groups, obtained in the knowledge questionnaire before the training program, was 15.10±4.66, becoming 21.99±3.93 points after the training received (p<0.001).

When analyzing the average scores according to the groups before and after the training workshop, significant differences were obtained in the average scores of the knowledge questionnaire. The score in the pre-workshop questionnaire in the EG was 16.29±5.48, becoming 21.44±4.62 after the training intervention (p<0.001). The score in the pre-workshop questionnaire in the CG was 13.85±3.23, becoming 22.41±3.03 after the intervention (p<0.001). Furthermore, when comparing the EG and the CG, significant differences were found between the total mean pre-workshop score (p=0.021) but not in the score obtained with the post-workshop questionnaire (p=0.965).

Statistically significant differences were found in each group when comparing the average knowledge scores before and after the training workshop (F=22.120; p<0.001), with no differences found when comparing these mean scores between both groups (F=0.880; p=0.351).

The average scores for each group based on the aspects measured in the knowledge questionnaire are listed in Table 4. Statistically significant differences were found in all the aspects contemplated, with an increase in the average scores when comparing these before and after the training workshop and in each group.

Pre-intervention and post-training intervention differences in the level of knowledge about the approach to alcohol consumption in each of the dimensions studied, according to the comparison group.

| Measured aspects | Experimental group | p* | Control group | p* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-workshopMean±SD | Post-workshopMean±SD | Pre-workshopMean±SD | Post-workshopMean±SD | |||

| Importance and magnitude of the problem | 3.56±1.97 | 5.02±1.59 | <0.001 | 3.21±1.59 | 5.28±1.54 | <0.001 |

| Concepts related to alcohol consumption | 4.90±1.87 | 5.76±1.39 | <0.001 | 4.33±1.61 | 6.18±0.99 | <0.001 |

| Detection and management of alcohol consumption | 5.85±1.88 | 7.15±1.67 | <0.001 | 4.95±1.30 | 7.59±1.31 | <0.001 |

| Impact of alcohol consumption on the family | 0.54±0.71 | 1.17±0.71 | <0.001 | 0.31±0.521 | 1.44±0.64 | <0.001 |

| Pharmacological treatment in drinking patients | 1.44±1.03 | 2.34±1.09 | <0.001 | 1.05±0.61 | 1.92±0.81 | <0.001 |

| Total | 16.29±5.48 | 21.44±4.62 | <0.001 | 13.85±3.23 | 22.41±3.01 | <0.001 |

SD: standard deviation; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

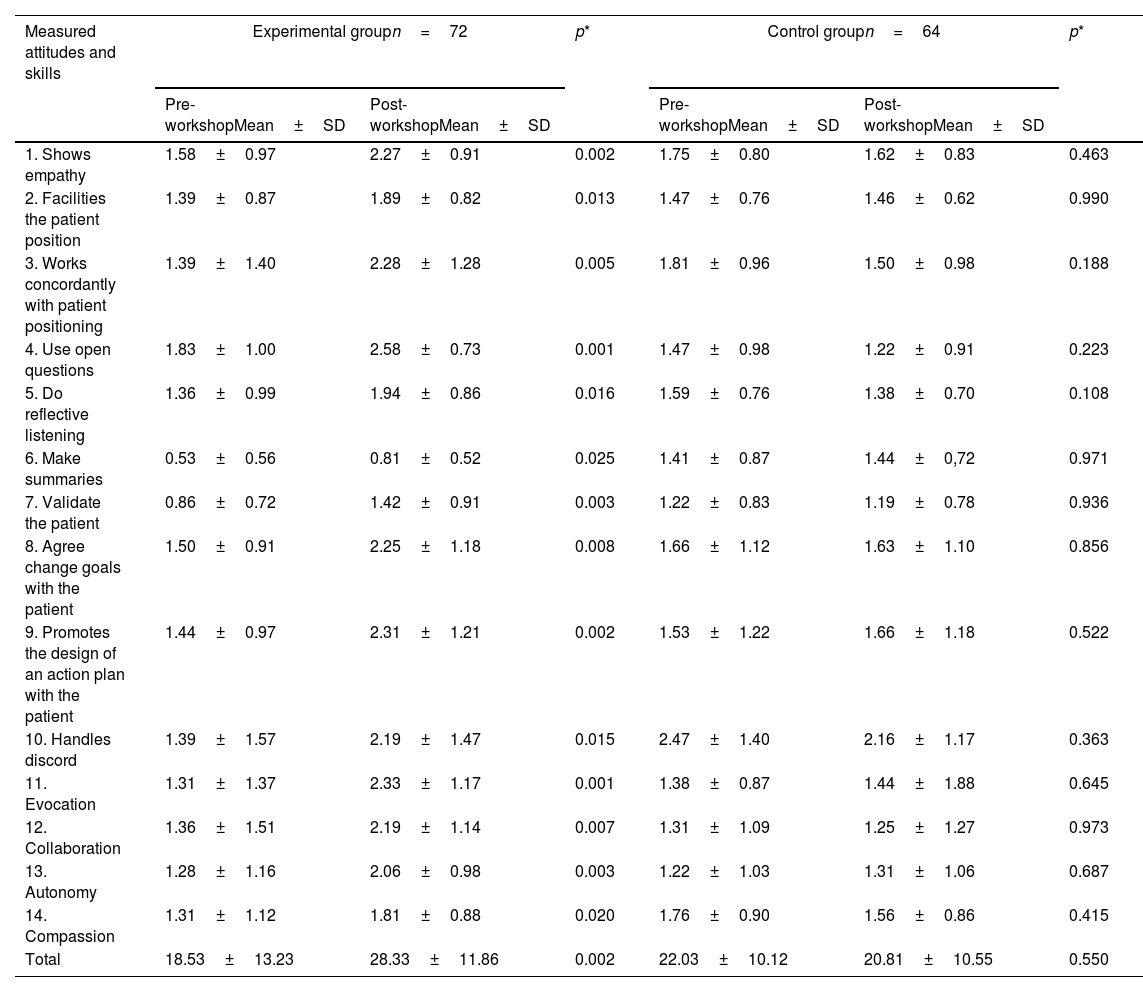

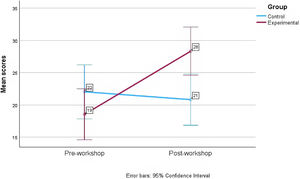

The mean score of the recordings in both groups before the training program was 20.20±11.83 (95%CI: 17.36–23.02; limits: 3–51). The mean score in the EG before the MI intervention was 18.53±13.23 and 28.33±11.86 after it (p=0.002), which represents an increase of 9.8 points on average in the EVEM scale (95%CI: 4.20–15.40).

Fig. 1 shows the mean scores obtained in each group before and after the MI intervention. Significant differences were found in the mean scores of all the items of the EG EVEM questionnaire before and after the MI intervention (F=10.186; p=0.002). No significant differences were found in the mean total scores or by dimensions evaluated in the EVEM questionnaire neither before nor after the intervention in the CG, that is, among those who had not received MI training.

Table 5 shows the mean scores obtained in all the items of the EVEM questionnaire in each group before and after the intervention. Scores increased in all scale items when comparing before and after intervention in the EG. In contrast, they remained similar in the CG.

Degree of competencies in motivational interviewing before and after the training workshop, according to the comparison group.

| Measured attitudes and skills | Experimental groupn=72 | p* | Control groupn=64 | p* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-workshopMean±SD | Post-workshopMean±SD | Pre-workshopMean±SD | Post-workshopMean±SD | |||

| 1. Shows empathy | 1.58±0.97 | 2.27±0.91 | 0.002 | 1.75±0.80 | 1.62±0.83 | 0.463 |

| 2. Facilities the patient position | 1.39±0.87 | 1.89±0.82 | 0.013 | 1.47±0.76 | 1.46±0.62 | 0.990 |

| 3. Works concordantly with patient positioning | 1.39±1.40 | 2.28±1.28 | 0.005 | 1.81±0.96 | 1.50±0.98 | 0.188 |

| 4. Use open questions | 1.83±1.00 | 2.58±0.73 | 0.001 | 1.47±0.98 | 1.22±0.91 | 0.223 |

| 5. Do reflective listening | 1.36±0.99 | 1.94±0.86 | 0.016 | 1.59±0.76 | 1.38±0.70 | 0.108 |

| 6. Make summaries | 0.53±0.56 | 0.81±0.52 | 0.025 | 1.41±0.87 | 1.44±0,72 | 0.971 |

| 7. Validate the patient | 0.86±0.72 | 1.42±0.91 | 0.003 | 1.22±0.83 | 1.19±0.78 | 0.936 |

| 8. Agree change goals with the patient | 1.50±0.91 | 2.25±1.18 | 0.008 | 1.66±1.12 | 1.63±1.10 | 0.856 |

| 9. Promotes the design of an action plan with the patient | 1.44±0.97 | 2.31±1.21 | 0.002 | 1.53±1.22 | 1.66±1.18 | 0.522 |

| 10. Handles discord | 1.39±1.57 | 2.19±1.47 | 0.015 | 2.47±1.40 | 2.16±1.17 | 0.363 |

| 11. Evocation | 1.31±1.37 | 2.33±1.17 | 0.001 | 1.38±0.87 | 1.44±1.88 | 0.645 |

| 12. Collaboration | 1.36±1.51 | 2.19±1.14 | 0.007 | 1.31±1.09 | 1.25±1.27 | 0.973 |

| 13. Autonomy | 1.28±1.16 | 2.06±0.98 | 0.003 | 1.22±1.03 | 1.31±1.06 | 0.687 |

| 14. Compassion | 1.31±1.12 | 1.81±0.88 | 0.020 | 1.76±0.90 | 1.56±0.86 | 0.415 |

| Total | 18.53±13.23 | 28.33±11.86 | 0.002 | 22.03±10.12 | 20.81±10.55 | 0.550 |

Continuing professional education is a process of active and lifelong learning to which health professionals have the right and obligation, which is intended to update and improve the knowledge, skills, and attitudes of health professionals facing scientific and technological developments and the demands and needs, both social and the health system itself.18 Thus, the specialists under training acquire the professional skills of their specialty in accredited schools and teaching units.

The results of the present study demonstrate the effectiveness of the training program designed on the one hand, to improve the level of knowledge of PC professionals in managing risky alcohol use. Furthermore, an increase in MI skills was demonstrated in the EG, which also received training in this type of communicational psychological therapy.

As noted in other studies,19 we have found a low level of knowledge among PC professionals about the health harms and consequences of excessive alcohol consumption and what strategy, or action plan should be followed to address this problem. We used the recommendations proposed by the PAPPS,17,20 a program that is a reference for many PC professionals in Spain.

It is known that a higher degree of knowledge is related to a more frequent practice of preventive management of risky alcohol use and a more proactive attitude.21 This level of knowledge is similar to that obtained in Romero's study.10 In our study, the level of knowledge improved after the training, the participants passed to answer correctly from 35% to 50% of the questions. However, the above-mentioned study showed a higher increase, with a 22.9% improvement after the intervention. The instructors in the training program were the same in both cases; therefore, this difference could be explained by various reasons related to the subjects who participated, such as a lower motivation or a lower percentage of resident participants.

The clinical communication skills of professionals have high relevance in the diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic processes of patients with risky alcohol use.22 Of the various interventions to address toxic substance abuse, MI-based interventions are among the most evident in reducing consumption and causing behavioral changes in patients.23–25

Regarding the attitudes and skills in MI evaluated in the participants, a significant improvement has been obtained, with an average on the EVEM scale of almost 10 points in the group of professionals who received the training intervention. If we compare the results obtained in the MI skills of our sample with the “MOTIVA” study,11 we found a lower mean score in our study with the EVEM scale, where EG professionals obtained an improvement of 13.89 points on average. In comparison, Barragan et al. conducted a more complete and extensive training program, with other activities to improve MI skills. MI training requires a minimum of teaching hours and a developmental process, with repetitive and maintained practices for the health professional to assimilate and internalize this approach or therapeutic spirit.26

Among the limitations of this study, a potential selection bias may occur because having participated in the study voluntarily presupposes a higher motivation, which can lead to an overestimation of the impact of the intervention. However, this bias is difficult to avoid, where there are also dropouts or withdrawals of participants due to different reasons. In our case, we had to exclude 15 professionals because they did not complete the initial questionnaires, which could be due to their low motivation.

Finally, we should point out the Hawthorne effect or observer bias.27 However, this bias does not affect the results significantly, and the fundamental thing is that both the video recordings captured before and after the training interventions were recorded under similar conditions.

In conclusion, a structured training program on managing risky alcohol use, aimed at PC health professionals, is effective in increasing knowledge about this health problem. Similarly, the results indicate that the MI training implemented has met the objective of significantly improving the skills of healthcare professionals in using this communication tool.

- •

Excessive alcohol consumption is an important health problem in the world, especially in Western countries.

- •

The Primary Care level is the most appropriate setting for a preventive and intervention approach. Professionals have close contact with patients and can carry out longitudinal follow-up.

- •

Evaluating the effectiveness of training programs, such as those focused on motivational interviewing, is necessary before recommending their implementation.

- •

The tested training program has shown to be effective in increasing knowledge and skills to manage patients with risky excessive alcohol consumption.

- •

Professionals significantly increased their knowledge and skills in motivational interviewing after the conducted training intervention.

The study was approved for Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Reina Sofia Hospital of Cordoba (January 8, 2021; reference: 4930) and written consent has been obtained from all patients.

FundingThis research was funded by the call for research and innovation projects in the field of Primary Care, Regional hospitals, and High-resolution hospital centers of the Public Health System of Andalusia in 2021 by the Progreso y Salud Foundation of the Ministry of Health and Families of the Junta de Andalucía, with EXP. No. AP-0001-2020-C1-F2.

Also received the Specialist Postdoctoral Contract by the Ministry of Health and Families (No. Exp: RH-0134-2020), and the “Isabel Fernández” scholarships for research projects, 2021. Andalusian Society of Family and Community Medicine (SAMFYC).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

We would like to thank Nutraceutical Translations for the translation of this manuscript into English.

To all the health professionals of the ALCO-AP Collaborative Group, for their participation in the execution of this study.

| Participants | Center |

|---|---|

| Alejandro Camacho Franco | DCCU Córdoba |

| Alicia Moscoso Jara | Peñarroya-Pueblonuevo |

| Alicia Valenzuela Gómez | Occidente Azahara |

| Ana González de la Rubia | Villarrubia |

| Ana Morilla Roldán | Pozoblanco |

| Ana Roldan Villalobos | Carlos Castilla del Pino |

| Antonia Carmona Priego | Levante Norte |

| Antonia Toledano Medina | Montoro |

| Antonio León Dugo | Aeropuerto |

| Carmen Jurado Porcuna | Levante Norte |

| Carmen Rodríguez Buza | Carlota |

| Carmen Sánchez Aguilar | Occidente Azahara |

| Celia Pérula Jiménez | Montoro |

| Cristina Rojas Prats | La Carlota |

| Cristina Ruiz Rull | Montoro |

| Elena De Rodrigo Tobías | Almodóvar |

| Elena María De Dios González | Bujalance |

| Enrique Martínez Martínez | Hospital Universitario de Villalba |

| Esperanza Romero Rodríguez | Carlos Castilla del Pino |

| Estrella Castro Martín | Occidente Azahara |

| Eva María Sánchez Cañete | Polígono Guadalquivir |

| Fátima Bravo Ábalos | Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía |

| Fernando Jesús González Martínez | Posadas |

| Francisco López Cañas | Higuerón |

| Gertrudis Montes Redondo | Santa Rosa |

| Helena Cruz Terrón | Aeropuerto |

| Inés Gutiérrez París | Almodóvar |

| Isabel Jabato Moreno | Aeropuerto |

| Jesús González Lama | Cabra |

| Jesús Villar | Poniente |

| José Angel Fernández García | Villarrubia |

| José Tomás Linares | Sector Sur |

| Juan Baleato Gómez | Villarrubia |

| Juan José León Serrano | Levante Norte |

| Juan Marcos Baños | Villafranca |

| Julia Hervás Jerez | Sector Sur |

| Laura Aranda Domínguez | Sector sur |

| Laura Martín Guerra | Aeropuerto |

| Manuel Marín Agredano | Pozoblanco |

| Manuela Urbano Priego | Occidente Azahara |

| Margarita Fernández Poyatos | Levante norte |

| María Angeles Quesada Román | Lucano |

| María Bello Castro | Montilla |

| María Carmen Luna Moreno | Cordoba |

| María Carmen Ocaña Rodríguez | Baena |

| María del Carmen Castillo | Occidente Azahara |

| Maria del Carmen Membiela Jurado | Sector Sur |

| María Dolores López Espejo | Occidente Azahara |

| María Isabel López Estepa | Aeropuerto |

| María Luisa Soria Cabrera | Villarrubia |

| María Luisa Trigueros Guerra | Occidente Azahara |

| María Reyes Martínez Guillén | Aeropuerto |

| Maria Carmen Membiela Jurado | Luque |

| Marina Guijarro Blanco | Poniente |

| Marta Espejo Marín | Occidente Azahara |

| Miguel Muñoz Álamo | Occidente Azahara |

| Miguel Relaño Pedregal | Villafranca |

| Nazaret María Vargas Berni | Aeropuerto |

| Nazaret Morales Delgado | Poniente |

| Raquel Aguilera Muñoz | Córdoba |

| Raquel Gracia Rodríguez | Bujalance |

| Raquel Sauces Carrillo | Bujalance |

| Rocío Luna Cuevas | Sector Sur |

| Rodrigo Ruz Muriel | Área Sur de Córdoba |

| Rodrigo Sebastian Fernández Márquez | Lucena |

| Rosalía Serrano Berni | Occidente Azahara |

| Sharon Stefany Marín González | Santa Rosa |

| Sofía Chico Tierno | Occidente Azahara |

| Tránsito Porras Castro | Villarrubia |