Sex workers can be disadvantaged in terms of overall health due to challenging living and working conditions. This research aimed to evaluate the health status and experiences related to sexually transmitted infections (STDs) of unregistered transgender sex workers in Turkey.

DesignIt employed a phenomenological qualitative research design.

SiteData were collected in Istanbul between March 2021 and November 2021.

ParticipantsData were collected through in-depth interviews involving 24 people (19 sex workers and 5 physicians).

MethodsKey statements were listed during data analysis, and clusters of meanings were formed based on these statements. The participants’ statements were used for contextual and structural descriptions.

ResultsSex workers suffer from chronic illnesses such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, allergic diseases, and neurological disorders. Among the health issues affecting them, the most notable ones are STDs, psychological problems, and the risk of suicide. Sex workers also face a dilemma between choosing public hospitals and private hospitals. Majority of sex workers undergo regular testing for STDs, with the frequency varying from person to person. Reasons for not undergoing regular testing include lack of social security coverage, financial constraints, lack of information, and feeling undervalued. Some individuals are being subjected to mandatory testing.

ConclusionsIt is recommended that sex workers who seek and request healthcare services should be provided with detailed information and education, particularly regarding psychological problems and STDs.

Las trabajadoras sexuales pueden estar en desventaja en términos de salud general debido a las difíciles condiciones de vida y trabajo. Esta investigación tuvo como objetivo evaluar el estado de salud y las experiencias relacionadas con las infecciones de transmisión sexual (ITS) de las trabajadoras sexuales transgénero no registradas en Turquía.

DiseñoSe utilizó un diseño de investigación cualitativa fenomenológica.

EmplazamientoLos datos se recopilaron en Estambul entre marzo del 2021 y noviembre del 2021.

ParticipantesLos datos se recopilaron a través de entrevistas en profundidad con 24 personas (19 trabajadoras sexuales y 5 médicos).

MétodoSe enumeraron declaraciones clave durante el análisis de datos y se formaron grupos de significados basados en estas declaraciones. Las declaraciones de los participantes se utilizaron para descripciones contextuales y estructurales.

ResultadosLas trabajadoras sexuales enfrentan enfermedades crónicas como asma, enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica, diabetes, alergias y trastornos neurológicos. Las ITS, problemas psicológicos y el riesgo de suicidio son los más destacados entre sus problemas de salud. Existe un dilema en la elección entre hospitales públicos y privados. Aunque la mayoría se somete regularmente a pruebas de ITS, la frecuencia varía individualmente. No realizar pruebas regulares se debe a la falta de seguridad social, limitaciones financieras, escasa información y sentimientos de menosprecio. Algunas están sujetas a pruebas obligatorias.

ConclusionesSe recomienda que se proporcione información detallada y educación a las trabajadoras sexuales que buscan y solicitan servicios de atención médica, especialmente en lo que respecta a problemas psicológicos e ITS.

It is believed that the origin of sex work dates back to the Mesopotamian civilization, and is known to have spread to ancient Greece, Rome, Japan, and China, each with different connotations attached to it.1–3

Sex workers who work in brothels under legal conditions have their insurance premiums paid and have social security coverage. Sex work in Turkey is regulated by law, but unregistered sex workers are people who do not work in official brothels and are not subject to these legal regulations.4 Although the exact numerical data is unknown, it is known that there are more than 100,000 sex workers in Turkey. Out of this, 3000 are registered in 56 brothels in Turkey.5 It is also estimated that there are 15,000 healthcare injunction (court-ordered treatment) involving women; therefore, there are at least 85,000 unregistered sex workers.6 On the other hand, unregistered sex workers either individually pay their insurance premiums to the extent of their resources or are unable to pay.7,8

Among the common diseases experienced are malnutrition, weak immune systems, sleep disorders, dermatological diseases, chronic liver diseases due to high alcohol use, various STDs, rheumatic and orthopedic disorders. Among these, the most widespread and significant area is STDs.9–12 Although a report published in Turkey in 2010 indicated that 92.2% of interviewed sex workers stated that they used condoms with their clients, hurried dealings in informal sex work, inequalities in the healthcare system, lack of social security in most cases, inadequate knowledge about infections other than HIV, limitations in access to preventive and curative services can increase risky sexual behaviors and delay the treatment process.13 Studies on sex workers in Turkey mostly include registered sex workers. There are very few studies on unregistered sex workers, which mostly include identities such as foreign nationals, transgenders and homosexuals.4 The aim of this study is to evaluate the health status and STD-related experiences among unregistered transgender sex workers in Turkey.

Materials and methodsStudy designDrawing on qualitative research techniques, the study employed a phenomenological research design. This article represents a section of a thesis focusing on the findings related to the health status and experiences of sex workers with STDs.

Participant recruitmentThe study population consisted of unregistered sex workers and physicians (who have a patient–physician relationship with sex workers). Relying on previous studies and written reports, reaching a total of 28 individuals, including 21 sex workers and 7 physicians was targeted. Through snowball sampling via associations and social networks, 19 sex workers and 5 physicians were ultimately interviewed. Sex workers were selected based on their years of work to ensure diverse perspectives, while physicians were chosen for their specialty areas relevant to sex workers health.

Data collectionSemi-structured in-depth interview forms were created by reviewing relevant research and examining current legislation and conventions on health rights. Researchers (*,**) with qualitative research experience prepared the forms. Initially, an interview form was created for the sex workers, and then, and it was later adapted for the physicians in a way that it could be related to the questions of the sex workers. The semi-structured interview form designed for sex workers included questions related to socio-demographic information, past or current health issues, the medical specialties they consulted, the hospitals they visited, the reasons for their hospital preferences, their experiences with STDs, and their practices related to getting tested for STDs. The form created for physicians included questions on socio-demographic information, the complaints or issues for which sex workers sought medical care, as well as sex workers’ experiences with STDs. Interviews, lasting 20–60 minutes, were conducted between March and October 2021 through various methods including home visits, video calls, and a clinic visit for one physician. All interviews were audio-recorded with consent. A single researcher (**) conducted the interviews in this study.

Data analysisThe audio recordings obtained during the interviews were transcribed and converted into plain text format using the Word program. At the beginning of the data analysis, a code list was created with the support of literature to identify codes that could be used in the research; this list was later expanded as the interview data were examined. Pseudonyms and code names were used for confidentiality. A single researcher (**) carried out the transcription of the audio recordings and the analysis, coding, interpretation, and reporting of the data. Two researchers (*,**) carried out the evaluation of the codes and themes. In the data analysis, key expressions were listed, and based on these expressions, clusters of meaning were formed, and the statements of the participants were used in narrative and structural descriptions. Content analysis was conducted with MAXQDA 2020.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Istanbul Faculty of Medicine (No.139019, dated 18.03.2021) and all participants signed the informed consent.

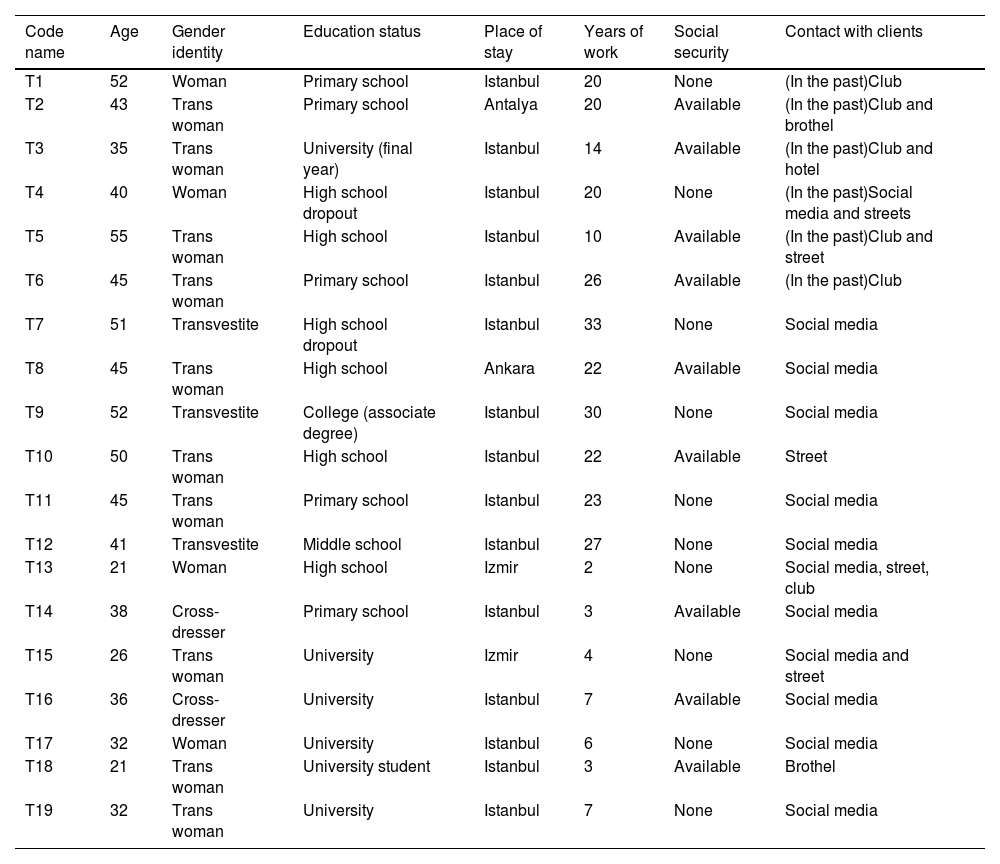

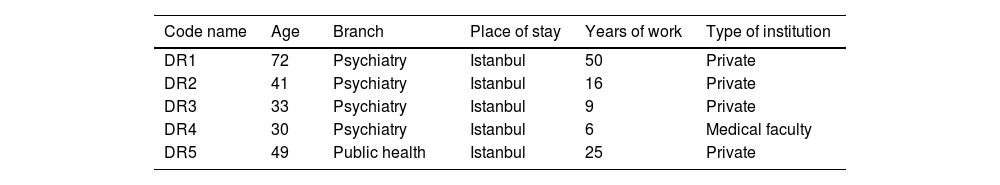

ResultsThe age, self-identified gender identities, education status, place of residence, active years of work, social security status, and methods of reaching clients of the interviewed sex workers are provided in Table 1; the age, specialization, place of residence, years of practice, and type of institution (they worked at) of the physicians are presented in Table 2.

Basic characteristics of sex workers.

| Code name | Age | Gender identity | Education status | Place of stay | Years of work | Social security | Contact with clients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | 52 | Woman | Primary school | Istanbul | 20 | None | (In the past)Club |

| T2 | 43 | Trans woman | Primary school | Antalya | 20 | Available | (In the past)Club and brothel |

| T3 | 35 | Trans woman | University (final year) | Istanbul | 14 | Available | (In the past)Club and hotel |

| T4 | 40 | Woman | High school dropout | Istanbul | 20 | None | (In the past)Social media and streets |

| T5 | 55 | Trans woman | High school | Istanbul | 10 | Available | (In the past)Club and street |

| T6 | 45 | Trans woman | Primary school | Istanbul | 26 | Available | (In the past)Club |

| T7 | 51 | Transvestite | High school dropout | Istanbul | 33 | None | Social media |

| T8 | 45 | Trans woman | High school | Ankara | 22 | Available | Social media |

| T9 | 52 | Transvestite | College (associate degree) | Istanbul | 30 | None | Social media |

| T10 | 50 | Trans woman | High school | Istanbul | 22 | Available | Street |

| T11 | 45 | Trans woman | Primary school | Istanbul | 23 | None | Social media |

| T12 | 41 | Transvestite | Middle school | Istanbul | 27 | None | Social media |

| T13 | 21 | Woman | High school | Izmir | 2 | None | Social media, street, club |

| T14 | 38 | Cross-dresser | Primary school | Istanbul | 3 | Available | Social media |

| T15 | 26 | Trans woman | University | Izmir | 4 | None | Social media and street |

| T16 | 36 | Cross-dresser | University | Istanbul | 7 | Available | Social media |

| T17 | 32 | Woman | University | Istanbul | 6 | None | Social media |

| T18 | 21 | Trans woman | University student | Istanbul | 3 | Available | Brothel |

| T19 | 32 | Trans woman | University | Istanbul | 7 | None | Social media |

Basic characteristics of physicians.

| Code name | Age | Branch | Place of stay | Years of work | Type of institution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DR1 | 72 | Psychiatry | Istanbul | 50 | Private |

| DR2 | 41 | Psychiatry | Istanbul | 16 | Private |

| DR3 | 33 | Psychiatry | Istanbul | 9 | Private |

| DR4 | 30 | Psychiatry | Istanbul | 6 | Medical faculty |

| DR5 | 49 | Public health | Istanbul | 25 | Private |

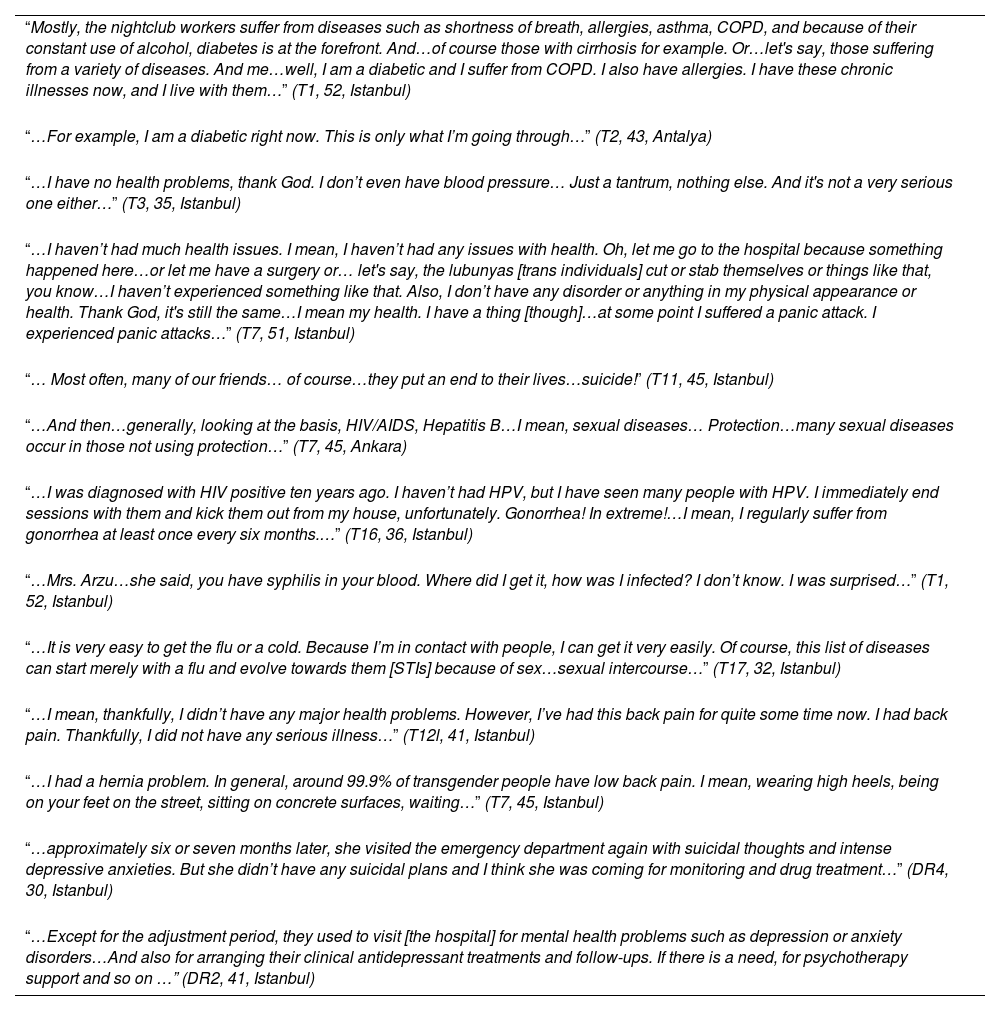

The interviewees talked about two types of health problems: STDs and other chronic diseases (see Table 3). Other chronic diseases were divided into two as physical and mental. In the analysis, we identified two sub-themes related to health problems: the effect of the customer and the effect of the working conditions. Other chronic diseases mostly caused by working conditions include allergic diseases, asthma, COPD, diabetes, gallbladder problems, oral-dental health problems, and orthopedic-related complaints. In addition, the mental problems mentioned by some of the interviewees are also important. STDs, on the other hand, were mostly customer related. The interviewed physicians, mostly psychiatrists, reported that the most common reasons for sex workers seeking medical help were post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, psychotic symptoms, anxiety disorders, and conversion disorder.

Exemplar quotes relating to health problems.

| “Mostly, the nightclub workers suffer from diseases such as shortness of breath, allergies, asthma, COPD, and because of their constant use of alcohol, diabetes is at the forefront. And…of course those with cirrhosis for example. Or…let's say, those suffering from a variety of diseases. And me…well, I am a diabetic and I suffer from COPD. I also have allergies. I have these chronic illnesses now, and I live with them…” (T1, 52, Istanbul) |

| “…For example, I am a diabetic right now. This is only what I’m going through…” (T2, 43, Antalya) |

| “…I have no health problems, thank God. I don’t even have blood pressure… Just a tantrum, nothing else. And it's not a very serious one either…” (T3, 35, Istanbul) |

| “…I haven’t had much health issues. I mean, I haven’t had any issues with health. Oh, let me go to the hospital because something happened here…or let me have a surgery or… let's say, the lubunyas [trans individuals] cut or stab themselves or things like that, you know…I haven’t experienced something like that. Also, I don’t have any disorder or anything in my physical appearance or health. Thank God, it's still the same…I mean my health. I have a thing [though]…at some point I suffered a panic attack. I experienced panic attacks…” (T7, 51, Istanbul) |

| “… Most often, many of our friends… of course…they put an end to their lives…suicide!” (T11, 45, Istanbul) |

| “…And then…generally, looking at the basis, HIV/AIDS, Hepatitis B…I mean, sexual diseases… Protection…many sexual diseases occur in those not using protection…” (T7, 45, Ankara) |

| “…I was diagnosed with HIV positive ten years ago. I haven’t had HPV, but I have seen many people with HPV. I immediately end sessions with them and kick them out from my house, unfortunately. Gonorrhea! In extreme!…I mean, I regularly suffer from gonorrhea at least once every six months.…” (T16, 36, Istanbul) |

| “…Mrs. Arzu…she said, you have syphilis in your blood. Where did I get it, how was I infected? I don’t know. I was surprised…” (T1, 52, Istanbul) |

| “…It is very easy to get the flu or a cold. Because I’m in contact with people, I can get it very easily. Of course, this list of diseases can start merely with a flu and evolve towards them [STIs] because of sex…sexual intercourse…” (T17, 32, Istanbul) |

| “…I mean, thankfully, I didn’t have any major health problems. However, I’ve had this back pain for quite some time now. I had back pain. Thankfully, I did not have any serious illness…” (T12l, 41, Istanbul) |

| “…I had a hernia problem. In general, around 99.9% of transgender people have low back pain. I mean, wearing high heels, being on your feet on the street, sitting on concrete surfaces, waiting…” (T7, 45, Istanbul) |

| “…approximately six or seven months later, she visited the emergency department again with suicidal thoughts and intense depressive anxieties. But she didn’t have any suicidal plans and I think she was coming for monitoring and drug treatment…” (DR4, 30, Istanbul) |

| “…Except for the adjustment period, they used to visit [the hospital] for mental health problems such as depression or anxiety disorders…And also for arranging their clinical antidepressant treatments and follow-ups. If there is a need, for psychotherapy support and so on …” (DR2, 41, Istanbul) |

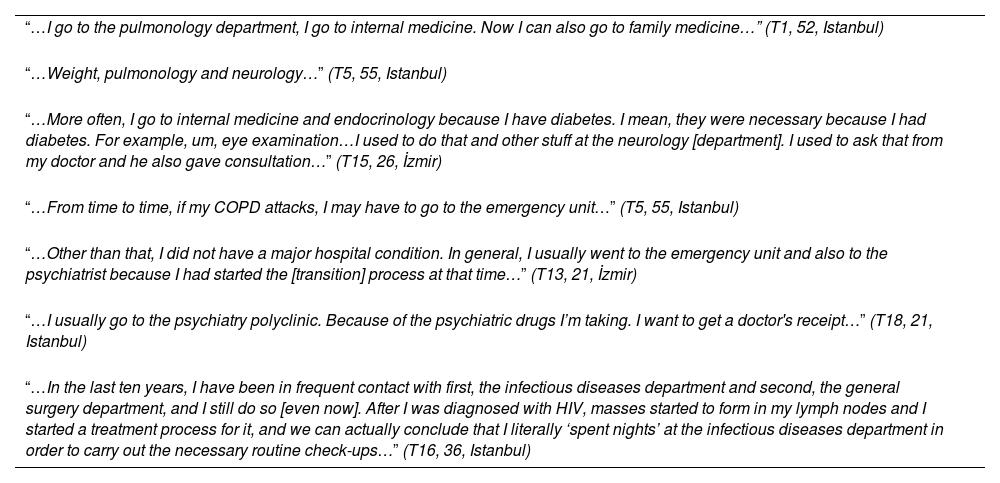

The polyclinics/specialties most commonly visited in relation to the health problems of sex workers can vary. Particularly, individuals with chronic illnesses often mentioned seeking medical help in internal medicine fields such as general medicine, endocrinology, pulmonology, and neurology (see Table 4). As expected, the psychiatry department was the most frequently visited in cases of psychological symptoms and complaints. They seek healthcare services from the infectious diseases branch and related specialties for complaints related to STDs.

Exemplar quotes relating to medical departments.

| “…I go to the pulmonology department, I go to internal medicine. Now I can also go to family medicine…” (T1, 52, Istanbul) |

| “…Weight, pulmonology and neurology…” (T5, 55, Istanbul) |

| “…More often, I go to internal medicine and endocrinology because I have diabetes. I mean, they were necessary because I had diabetes. For example, um, eye examination…I used to do that and other stuff at the neurology [department]. I used to ask that from my doctor and he also gave consultation…” (T15, 26, İzmir) |

| “…From time to time, if my COPD attacks, I may have to go to the emergency unit…” (T5, 55, Istanbul) |

| “…Other than that, I did not have a major hospital condition. In general, I usually went to the emergency unit and also to the psychiatrist because I had started the [transition] process at that time…” (T13, 21, İzmir) |

| “…I usually go to the psychiatry polyclinic. Because of the psychiatric drugs I’m taking. I want to get a doctor's receipt…” (T18, 21, Istanbul) |

| “…In the last ten years, I have been in frequent contact with first, the infectious diseases department and second, the general surgery department, and I still do so [even now]. After I was diagnosed with HIV, masses started to form in my lymph nodes and I started a treatment process for it, and we can actually conclude that I literally ‘spent nights’ at the infectious diseases department in order to carry out the necessary routine check-ups…” (T16, 36, Istanbul) |

When examining which health institutions, the interviewees most frequently applied to, sex workers gave answers under two main headings: private institutions and state institutions (see Table 5). In the analysis, three sub-themes related to the visited health institutions emerged: exclusion/transphobia, economic situation, competence. Many of the sex workers, due to financial constraints, stated that they are obliged to choose public hospitals. At the same time, the public institutions are also chosen during healthcare access for reasons such as the perception of good quality service, proximity to their homes, and general habits. The reasons for “private hospitals” preference are associated with the advantages provided by private hospitals, and is often related to their financial situation as well. The lack of social security coverage also obliges them to seek healthcare services at private hospitals. Their choice of seeking healthcare at private hospitals is influenced by the belief in less exposure to phobias and discrimination. Some sex workers prioritize choosing their healthcare providers over hospital preferences. They select specific doctors from certain specialties for their specific complaints and illnesses, and they schedule appointments with those individuals when necessary. The crucial and significant factor in these choices is the ethical approach of the doctors, which includes ensuring they are free from discrimination and hate speech.

Exemplar quotes relating to health institutions.

| “…I go to the um…sağlık ocağı. I usually go there to get my medical prescriptions…” (T10, 50, İstanbul) |

| “…I have gone to the sağlık ocağı just to get my routine medical prescriptions…” (T15, 26, İzmir) |

| “…I usually chose whatever is suitable for me at that moment. If my financial situation is ok, if it is favorable, for example, I’d chose a private hospital…” (T8, 45, Ankara) |

| “…Private hospital. Because I don’t have insurance. I usually prefer going to a private hospital…” (T17, 32, Istanbul) |

| “…for me…the private, you know, for example, for psychiatry, I prefer the private because I am afraid that I will not be given enough attention or be exposed to transphobia in a public hospital. On the one hand, I think I wouldn’t be given enough care. That's why, for example, I prefer a private clinic for psychiatry…” (T18, 21, Istanbul) |

| “…because we can never afford the private hospitals. We are forced to go to the public hospital. So, it is impossible for me to go to a private hospital…” (T11, 45, Istanbul) |

| “Apart from that, I prefer the teaching and research hospitals more because I think the teaching and research hospitals tend to be a little more trans-inclusive. Or just a little better. Of course this is not always the case. For example, the Taksim First Aid, I mean the old name of the place…and this is a hospital that I mostly prefer. It is relatively close to where I live, and also because it is a hospital that feels a little more safer for me. Yeah, for me, I think they give better attention to people in the teaching and research hospitals. But, this is what it is about I guess….In other words, the fact that it's a teaching and research hospital and all…” (T18, 21, Istanbul) |

| “…And of course, the thing is. I prefer medical faculties. For example, when I have a problem or let's say I want to go to the urologist, I definitely choose Cerrahpaşa. Or…what's it called… the Taksim first aid…I won’t choose that. Because Cerrahpaşa is more experienced with trans people and knows what it means to work with trans people. That's why I don’t prefer to go to other hospitals. Because when it's about the genitals, there will be a lot of things about my trans identity. Alternatively, when it comes to endocrinology, I will probably prefer Cerrahpaşa again…” (T18, 21, Istanbul) |

| “For example, right now I want to change my [breast] silicones and all… And what do you do for this? you can’t just go to any doctor you want. There are certain doctors you go to…the doctors we go to…who take care of us. This applies to everything, and not just for the examinations, you know. Even if I should go to the hairdresser, it’ll be like this…” (T19, 32, Istanbul) |

The behavior of the interviewees to be tested for STDs is shaped under three headings: regular testing, not having regular testing, and compulsory testing (see Table 6). In the data analysis of sex workers’ testing behavior, four sub-themes emerged: accessibility, free testing, anonymization, and self-worth. The main reason for regular testing is the need to be aware of diseases and their consequences. The narratives suggest that the behavior of undergoing regular testing can be associated with the existence of free and anonymous testing centers. Some of the interviewed sex workers had stated that they did not undergo “regular testing” for STDs and expressed their reasons as not having unprotected sex, difficulty in accessing healthcare, heavy workload, reluctance to pay for the tests and feeling worthless. Majority of sex workers interviewed express that subjecting individuals to mandatory testing and disclosing test results without their consent is a violation of personal rights. Instead of mandatory testing, they believe that sex workers should be educated, informed, and made conscious about STDs. Some of the interviewees narrated that at some point in their lives, they had to undergo “compulsory testing”.

Exemplar quotes relating to getting tested for STIs.

| “…I definitely do [the tests]. Even though I’m at home right now, I definitely get it done once every four or five months. Even though I don’t have to, I still get it done…” (T2, 43, Antalya) |

| “…I had it done, but there was nothing. I do [regular testing]… I do my blood tests. When I go for full testing, I do them all. Nothing happens though. I’m already very careful about this [STIs] for years now. Because until now, I haven’t had even gonorrhea. Because I’m very careful…” (T10, 50, Istanbul) |

| “…I mean, ever since I became aware of my own gender identity and sexual orientation, I have had my routine tests done every three months on a regular basis. I mean, with the pandemic, together with what I do in my sex work, I get it done more often. I do it monthly…” (T15, 26, İzmir) |

| “…I do regular blood tests for a minimum of three months…” (T16, 36, Istanbul) |

| “…I used to do it once every two months in Şişli when I was working. There is a free test center. I was doing it there…” (T13, 21, İzmir) |

| “…I used to have my ELISA tests or something done, or I would sometimes go to HIV anonymous testing centers…” (T15, 26, İzmir) |

| “…I can say that I had it done three times in three years. I mean that it's like once a year…” (T19, 32, Istanbul) |

| “…For example, I can’t remember the last time I had an HIV test or something. For example, I guess HPV tests are being carried out, as far as I know. [But] I don’t think I can get these…Work and…you know, the stress, workload, fatigue and many other things that work brings. Actually, I see myself as very worthless in this kind of country, and I don’t even feel the need to test because of this sometimes, I mean, I said [to myself], I don’t know when last I had an HIV test…” (T18, 21, Istanbul) |

| “…Anyways, I don’t have sex without condoms; besides, there is no koli[customers], there's nothing…” (T12, 41, Istanbul) |

| “…Yes, like I said, in the past, during the times of the police, we the employees of that place, had to undergo tests every month. For example, we weren’t allowed inside the clubs when we don’t provide an HIV test on the 1st of every month…” (T4, 40, Istanbul) |

| “…For example, at my workplace, it was compulsory. All tests had to be done every three months. When something little shows, your [work] document is confiscated. I think it's good, it's a good thing…” (T2, 43, Antalya) |

| “…I think testing is very good. I think it's very good in terms of health. It is very important for both the [sex] worker and their customers. The customers could be married… and can contract a disease from a woman and later infect their wives. Or infect their lovers…” (T7, 51, Istanbul) |

| “…The compulsory testing is of course a violation of human rights. I mean, people aren’t like that. You educate people, you raise awareness. Of course, you don’t have to force it…” (T5., 55, Istanbul) |

| “…So this…I mean prostitutes, I would say. Because that's the term for it. I mean the mandatory testing of prostitutes is definitely, and absolutely not done for them. I know this. I am sure of this. I mean, prostitutes are not subjected to compulsory because of consideration for their health…alternatively, if only these opportunities were provided to prostitutes, how much is provided, I really don’t know. If it was provided…if necessary information was given to women, if we could talk about sexual health in our education system. And if this sexual health education was given, then definitely, everybody, at a certain point would have wanted to undergo testing voluntarily when needed, not compulsorily…” (T18, 21, Istanbul) |

When examining the common health problems among sex workers, a wide range of health issues arise from their working conditions or through their clients. Many individuals suffer from chronic diseases such as asthma, COPD, diabetes, allergies, and neurological disorders. In a study conducted in an Ankara brothel, it was reported that 13.8% of sex workers had hypertension, 5.1% had diabetes, and 2.9% had been diagnosed with depression.14 Various psychiatric diseases described by the interviewees in our study as nervousness and panic attacks were also present as chronic illnesses. Some of the interviewees emphasized that the most significant consequence of depressive symptoms is suicide. Depression and suicides are frequently observed among sex workers. A report states that 60.4% of transgender sex workers have attempted suicide, compared to 38.4% among non-sex worker transgender individuals.15 Another study conducted in a brothel in Adana indicated that 48.1% of sex workers scored 17 or higher on the Beck Depression Scale.16 These high rates, compared to the general population, are quite significant when considering factors such as pressure and discrimination that may contribute to these issues within the context of gender identity and occupation. Some of the individuals we interviewed mentioned having infections such as HIV and syphilis. In one study, 20.4% of sex workers in brothels had experienced an STD, while another study reported a rate of 35.5%.14

The choice of private hospitals is often motivated by the desire to avoid stigmatization, the lack of social security coverage, and the expectation of better care. Economic factors play a prominent role in the preference for public hospitals. Some individuals mentioned that they prioritize selecting a specific doctor rather than a specific hospital. This preference may be influenced by the desire to minimize negative experiences during healthcare access. In general, recommendations from friends and personal experiences may have played a significant role in shaping these preferences. A study conducted with sex workers also revealed that the healthcare facilities sex workers visit vary from person to person, including primary healthcare centers, university hospital clinics, emergency departments, public hospitals, and private hospitals. In the same study, a transgender sex worker expressed refraining from public hospitals or primary healthcare centers to avoid being stigmatized, but instead went to the private hospitals.9 Additionally, a report published in the USA showed that transgender sex workers have a higher preference for emergency departments and low-cost clinics compared to non-sex workers.15 In another study conducted with LGBTI+ individuals in Turkey, 20.6% preferred public hospitals, 39.7% preferred private hospitals, and 39.7% preferred faculty hospitals.17 Looking at this context, public hospitals, although economically advantageous for disadvantaged groups, facilitate the experience of phobia and discrimination, while private hospitals are seen as a relatively less discriminatory and economically challenging option. This compels individuals to choose the option that causes them the least harm.

Sex workers disclosed that STDs tests were mostly done at the free/anonymous testing centers. There were also sex workers who had no knowledge of where to have STD tests done. Therefore, it is crucial to increase awareness and provide information about STDs and testing centers. Furthermore, research has shown that the availability of anonymous/free testing centers is one of the factors that encourages regular testing.18 The reasons for not undergoing regular testing were expressed as not engaging in unprotected sex, lack of time, and lack of knowledge about testing centers. The limited availability of anonymous/free testing centers indicates a deficiency in one of the fundamental criteria of the ‘right to health’, namely ‘availability’. Additionally, not knowing where tests can be conducted falls outside the scope of ‘accessibility to information’ – which is a sub criterion of ‘accessibility’. In a study, it was observed that 17% of the interviewed sex workers did not undergo regular testing. Reasons for not getting tested included not having time, avoiding unprotected sex, not experiencing any problems, not knowing that tests were available, not knowing where to get tested, and hesitating to seek healthcare.19 These findings are consistent with the findings of our study.

Some of the interviewees from our study had explained that they had undergone a compulsory STI test at some point in their lives. Although, purposely done in an effort to protect public health, the compulsory tests carried out in the Dermatology and Venereal Diseases Hospital known as Cancan in the 90s should be evaluated in the context of rights violations. This situation is considered to be contrary to the ethics of ‘acceptability’, which is one of the criteria for the ‘right to health’. Majority of the interviewees found the compulsory testing method to be wrong, humiliating and a violation of their rights. Therefore, it can be concluded that when access to healthcare is facilitated through education and informative campaigns instead of subjecting sex workers to mandatory testing, most individuals will adopt the behavior of regular testing.

Almost all the sex workers indicated that they did not engage in unprotected sexual activities, and explained their behavior being knowledgeable and conscious. According to a study, it was reported that 78% of sex workers always use condoms, while 2% never use condoms.19 In another study, it was observed that 89.8% of sex workers working in brothels use condoms.16

Study limitationsIn this study, unregistered sex workers were interviewed. Therefore, the results of the study cannot be generalized for all sex workers. Since majority of the physicians interviewed were psychiatrists, the opinions of physicians in other branches that also have frequent patient–physician relations with sex workers were not evaluated.

ConclusionEconomic difficulties and lack of social security hinder sex workers’ access to healthcare in the initial stage, thus, impacting their right to health. Detailed information should be provided to sex workers who seek and request healthcare services, with a particular focus on increasing their knowledge about psychological issues and STDs. Information about prevention methods should be increased, and access should be made easier. Access to HIV medication should be facilitated and made free.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Istanbul Faculty of Medicine (No. 139019, dated 18.03.2021) and all participants signed the informed consent.

FundingThe study did not receive funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This study was initially developed as part of a specialization thesis at the Istanbul University, Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, Department of Public Health. The authors would like to extend their sincerest gratitude to all the transgender sex workers and physicians who participated in this study. This study would not have been possible without their enormous contributions. The authors would also like to express gratitude to Muhtar Çokar for helpful insights and feedbacks.