To identify the association between glycemia control with level of diabetes knowledge, diabetes education, and lifestyle variables in patients with type 2 diabetes.

DesignCross-sectional analytical study.

SiteClinics of the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS), Mexico.

ParticipantsPatients with type 2 diabetes.

Main measurementsGlycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), glucose, and lipid profile levels were measured from fasting venous blood samples. Assessment of disease knowledge was performed using the Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire (DKQ-24). Systolic and diastolic blood pressure was measured. Weight and abdominal circumference were measured, as well as body composition using bioimpedance. Sociodemographic, clinical, and lifestyle variables were obtained.

ResultsA total of 297 patients were included, sixty-seven percent (67%) were women with a median of six years since the diagnosis of diabetes. Only 7% of patients had adequate diabetes knowledge, and 56% had regular knowledge. Patients with adequate diabetes knowledge had a lower body mass index (p=0.016), lower percentage of fat (p=0.008), and lower fat mass (p=0.018); followed a diet (p=0.004) and had received diabetes education (p=0.002), and to obtain information about their illness (p=0.001). Patients with low levels of diabetes knowledge had a higher risk of HbA1c≥7% (OR: 4.68; 95% CI: 1.48,14.86; p=0.009), as well as those who did not receive diabetes education (OR: 2.17; 95% CI: 1.21–3.90; p=0.009) and those who did not follow a diet (OR: 2.37; 95% CI: 1.01,5.55; p=0.046).

ConclusionInadequate knowledge of diabetes, lack of diabetes education, and dietary adherence are associated with poor glycemia control in patients with diabetes.

Identificar la asociación entre el control de la glicemia con el nivel de conocimiento, la educación y las variables de estilo de vida en pacientes con diabetes tipo 2.

DiseñoEstudio transversal analítico.

SitioClínicas del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, México.

ParticipantesPacientes con diabetes tipo 2.

Medidas principalesSe midió el nivel de hemoglobina glicosilada (HbA1c), glucosa y perfil de lípidos en ayuno. La evaluación del conocimiento de la enfermedad se realizó con el Cuestionario de Conocimiento de la Diabetes (DKQ-24). Se midió presión arterial, peso y circunferencia abdominal, así como la composición corporal con bioimpedancia. Las variables clínicas y de estilo de vida fueron registradas.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 297 participantes y 67% fueron mujeres, con una mediana de diagnóstico de diabetes de seis años. Solo 7% tuvo un conocimiento adecuado de la diabetes y 56% un conocimiento regular. Los pacientes con conocimiento adecuado de la diabetes tuvieron un índice de masa corporal más bajo (p = 0,016), seguían una dieta (p = 0,004), recibieron educación en diabetes (p = 0,002), y obtuvieron información de su enfermedad (p = 0,001). Los pacientes con bajo nivel de conocimiento tuvieron mayor riesgo de HbA1c ≥ 7% (OR: 4,68; IC 95%: 1,48-14,86; p = 0,009), así como aquellos sin educación en diabetes (OR: 2,17; IC 95%: 1,21-3,90; p = 0,009) y quienes no seguían una dieta (OR: 2,37; IC 95%: 1,01-5,55; p = 0,046).

ConclusiónEl conocimiento inadecuado de diabetes, la falta de educación en diabetes y adherencia a la dieta se asocian a un control glucémico deficiente en pacientes con diabetes.

In 2021, the prevalence of diabetes worldwide was estimated to be 10.5% with 536.6 million people having the disease and a projected increase to 783.2 million by the year 2045.1 In Mexico, the 2016 National Health Survey (known by its Spanish acronym ENSANUT) reported a total prevalence of 13.7% (9.5% diagnosed and 4.1% without a previous diagnosis), and only 31.8% were found to have glycemia control with a glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) of <7%.2

In the past two decades risk factors such as obesity, hypercaloric diet, and low physical activity have contributed to a higher risk of chronic complications and a higher risk of early incapacity or mortality in the population with diabetes.3–5

Diabetes education allows the patient to acquire better knowledge about the disease and gain abilities that promote self-care, which, in conjunction with medical attention, enable them to achieve goals for metabolic control and adopt a healthier lifestyle.6–8

It has been reported that greater diabetes knowledge is associated with better control of HbA1c and self-care behaviors in patients with diabetes.9 In the United States, a quarter of diabetic patients have limited health literacy regarding diabetes, while in Spain the level of health literacy is regular.10,11

At the same time, there is controversy regarding whether greater knowledge in diabetes is related to better HbA1c levels and therapeutic compliance of patients.12,13 It has been proposed that health education should be aimed at promoting a better lifestyle, not only improving knowledge about the disease.14

Nevertheless, there is evidence about the effect of structured educational interventions, be they individually or in group form, together with other interventions that favor metabolic control, like self-care behaviors, adherence to treatment, and healthier lifestyle, as well as preventive measures.15–18 The objective of the present study was to identify the association between glycemia control with level of diabetes knowledge, education, and lifestyle variables in patients with type 2 diabetes.

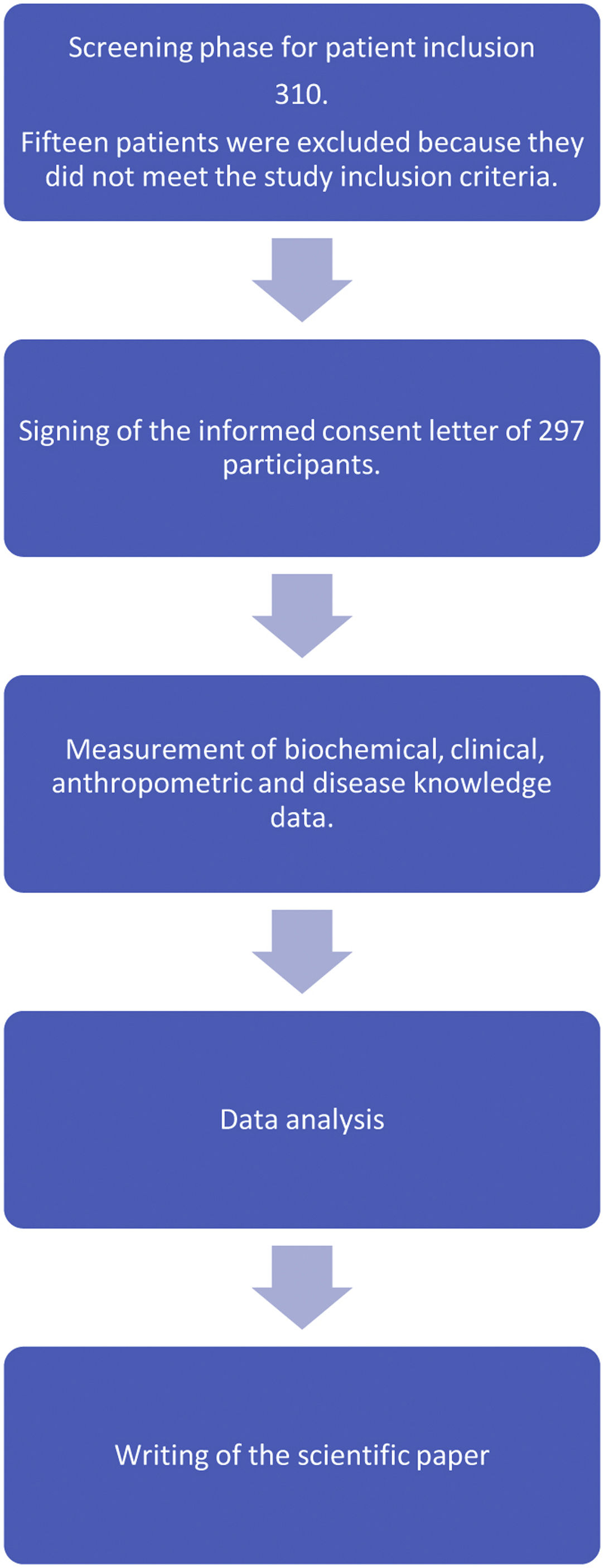

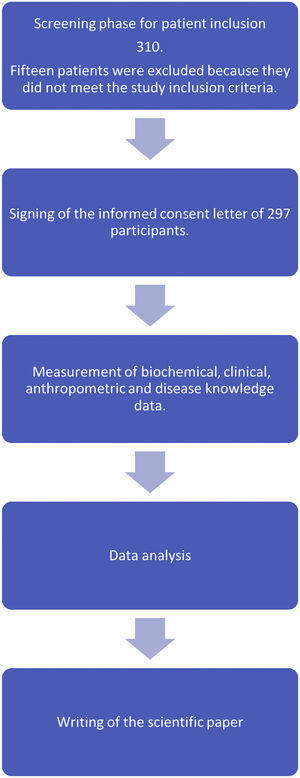

Materials and methodsStudy designAn analytical cross-sectional study was performed in patients with type 2 diabetes who attended four primary contact clinics at the Mexican Social Security Institute (known as the IMSS in Spanish) in Mexico City. Patients with diabetes are seen across three levels of care within the IMSS: 1. Patients receive family medicine attention and preventive medical care (first level of care); 2. Hospital-level specialized medical consultation in the areas of internal medicine, gynecology, endocrinology, and pediatrics, with medical consultation and hospitalization of patients (second level of care); 3. Greater specialization with medical sub-specialties and surgical intervention (third level of care).19 The present study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the IMSS.

Patients signed an informed consent after clarification of any questions or concerns regarding their participation in the study. Non-probability convenience sampling was used to select the sample of patients who were invited to participate when they attended their medical consultation during the study period.

The sample size was calculated with the formula to compare two proportions considering a previous study where the improvement in the level of knowledge and glycemia control was reported following an educational strategy: to find a proportion of glycemia control of 25% in those with an adequate level of knowledge versus 7% in the group with an inadequate level of knowledge, and a statistical power of 0.90. A sample size of 255 patients was obtained.20

Eligibility criteria for the participantsPatients with a diagnosis of diabetes for less than 20 years, who had the ability to read and write, were included in the study. Because the investigation was performed at the primary level of care, patients with serious diabetic complications such as advanced diabetic retinopathy or blindness, severe diabetic neuropathy and/or diabetic foot, and patients with chronic renal insufficiency who at the time of the study were undergoing substitute renal therapy, were excluded.

Socio-demographic and clinical assessmentsThe gathering of the socio-demographic data, clinical history, and identification of any co-morbidities, as well as the clinical assessment of the patients, was performed by a physician. Hypertension (HT) was identified in patients with a previous diagnosis. Blood pressure was measured twice with a mercury sphygmomanometer with an interval of five minutes between measurements and after a five-minute rest. The average value obtained from two measurements of arterial blood pressure was used for the analysis. Hypertension was diagnosed when the patient stated being on antihypertensive medication, or in those patients with a mean blood pressure value on more than two occasions of ≥130/80mm Hg at the time of participation in the study.21

Biochemical evaluationsTwelve hour fasting blood plasma glucose concentration, HbA1c, glucose, serum creatinine, and the lipid profile (total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL-c), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL-c)) were measured using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and automated photometry in a Cobas 800 c701 from Roche.

Anthropometric measurementsThe anthropometry was performed by two previously standardized, licenced nutritionists, using the method proposed by Habitch and following guidelines specified by Lohman et al.22,23 Weight and height were obtained using a TANITA® model TBF-215 scale: the percentage of fat was determined through bioimpedance of the lower segment, waist circumference (WC) was measured after determining the midpoint between the lowest rib and the superior border of the iliac crest on the right side, and hip circumference was determined by the greater diameter of the trochanters. Both measurements were done on three occasions and the average value of the second and third measurements was used for the analysis.

Assessment of diabetes knowledgePatients were asked to respond to the Diabetes Knowledge Questionnaire (DKQ-24). This questionnaire is validated to assess the level of knowledge in diabetes and is comprised of 24 questions that refer to etiology, signs and symptoms, diagnosis, pharmacological treatment, lifestyle, and the complications of type 2 diabetes. The questionnaire consists of 24 questions with three possible responses: “Yes,” “No,” or, “I don’t know.” The 24 items are grouped as: basic knowledge of the illness (10 items), blood sugar control (7 items), and preventing complications (7 items).24

The level of diabetes knowledge was classified according to total number of correct answers, low≤13, regular 14–19, and adequate≥20. Classification of the patient's level of knowledge was considered based on a previous study in a population with diabetes in México.25

Nutritional therapy and diabetes educationThe patient was considered to have received nutritional therapy when they had attended a diet and nutrition training session at the clinic on at least two separate occasions over the period of one year prior to the study. Diabetes education (DE) per se was considered when the patient had pursued, during the year prior to the study, at least six sessions of the educational course from the multi-disciplinary care program DiabetIMSS offered at primary care clinics of the IMSS. This information was obtained from the patient's clinical files.26 The course consists of one session per month over the period of one year and is provided by a specific team at each clinic.

Lifestyle and self-care variablesTo assess adherence to a diabetes care diet, patients were questioned regarding their habitual consumption of a healthy diet in the month prior to the study using the illustration of a plate that depicted the consumption of cereals and/or legumes, foods of animal and vegetable origin, fruits, and natural water. On a scale of 1–7, routine consumption of this ‘healthy plate’ was considered when achieving a score of 5 or greater, meaning that the patient was following a diet in order to care for their diabetes.

Investigators of the present study considered that patients were performing physical exercise when they followed the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations of at least 150min of aerobic physical activity of moderate intensity, distributed across at least three days per week.27 Patients were interviewed in order to discern perceptions about their current health status and how often they sought to obtain information about diabetes. Habits of smoking and alcohol consumption were also recorded.

Statistical analysisTo categorize the socio-demographic characteristics, clinical variables, and the level of diabetes knowledge, measures of frequencies and percentages were obtained, and, depending on their distribution, measures of central tendency and dispersion. The Chi-squared test was used to compare the difference between groups according to level of knowledge and diabetes education, lifestyle, and self-care behavior variables.

The one-way ANOVA test was used to compare the difference between groups in knowledge of diabetes (low, regular, and adequate) with measured lab parameters. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used when the data obtained had a non-parametric distribution. A logistic regression model was performed considering HbA1c as the dependent variable. The variables that were statistically significant, and variables theoretically associated with the blood glucose control, were included as follows: diabetes knowledge, age, sex, years since diagnosis with diabetes, diabetes treatment, previous education, exercise, and diet. A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

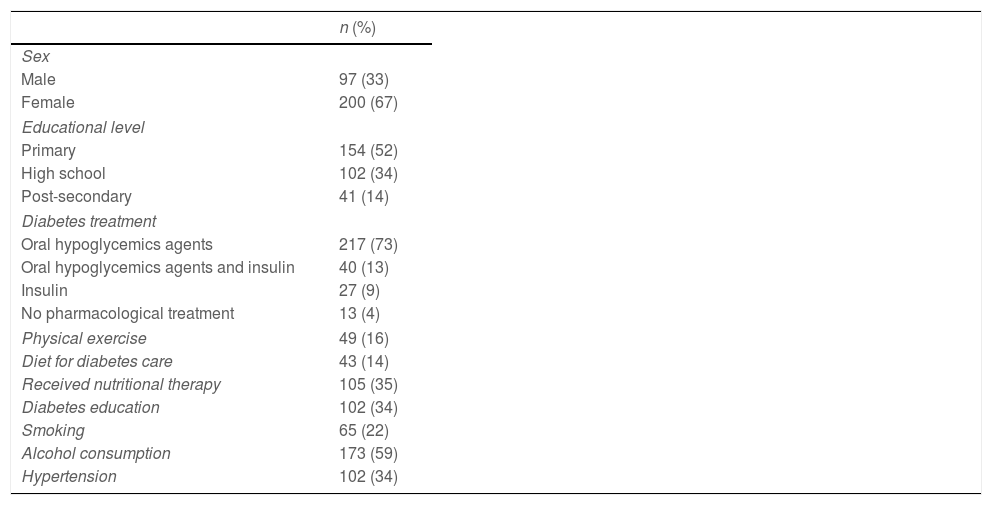

ResultsThe socio-demographic characteristics of the study population and the clinical and lifestyle variables are shown in Table 1. There were 297 patients included, 67% of whom were female. The mean age was 54 years, with a median of 6 years since diagnosis of diabetes. The most frequent treatment for diabetes was oral hypoglycemic drugs in 73%. An adequate diet was followed by 14% of participants, regular exercise was performed by 16%, and 34% of the studied population had received diabetic education.

Socio-demographic, clinical, and lifestyle characteristics of the study population, (n=297).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 97 (33) |

| Female | 200 (67) |

| Educational level | |

| Primary | 154 (52) |

| High school | 102 (34) |

| Post-secondary | 41 (14) |

| Diabetes treatment | |

| Oral hypoglycemics agents | 217 (73) |

| Oral hypoglycemics agents and insulin | 40 (13) |

| Insulin | 27 (9) |

| No pharmacological treatment | 13 (4) |

| Physical exercise | 49 (16) |

| Diet for diabetes care | 43 (14) |

| Received nutritional therapy | 105 (35) |

| Diabetes education | 102 (34) |

| Smoking | 65 (22) |

| Alcohol consumption | 173 (59) |

| Hypertension | 102 (34) |

| Average and standard deviation | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54.6±8.6 |

| Weight (kg) | 75.4±14.5 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 30.4±5.1 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 99.9±12.4 |

| Fat percentage (%) | 41.4±11.4 |

| Systolic arterial pressure (mm/Hg) | 125.3±15 |

| Diastolic arterial pressure (mm/Hg) | 83.5±10.1 |

| Glycated hemoglobin HbA1c (%) | 8.4±2.1 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 197.3±42 |

| LDL-c (mg/dL) | 112.9±32 |

| HDL-c (mg/dL) | 41.7±11.6 |

| Median and interquartile range | |

|---|---|

| Diabetes diagnosis (years) | 6 (3–11) |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 181 (137.5–241.5) |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 149.9 (119–205.5) |

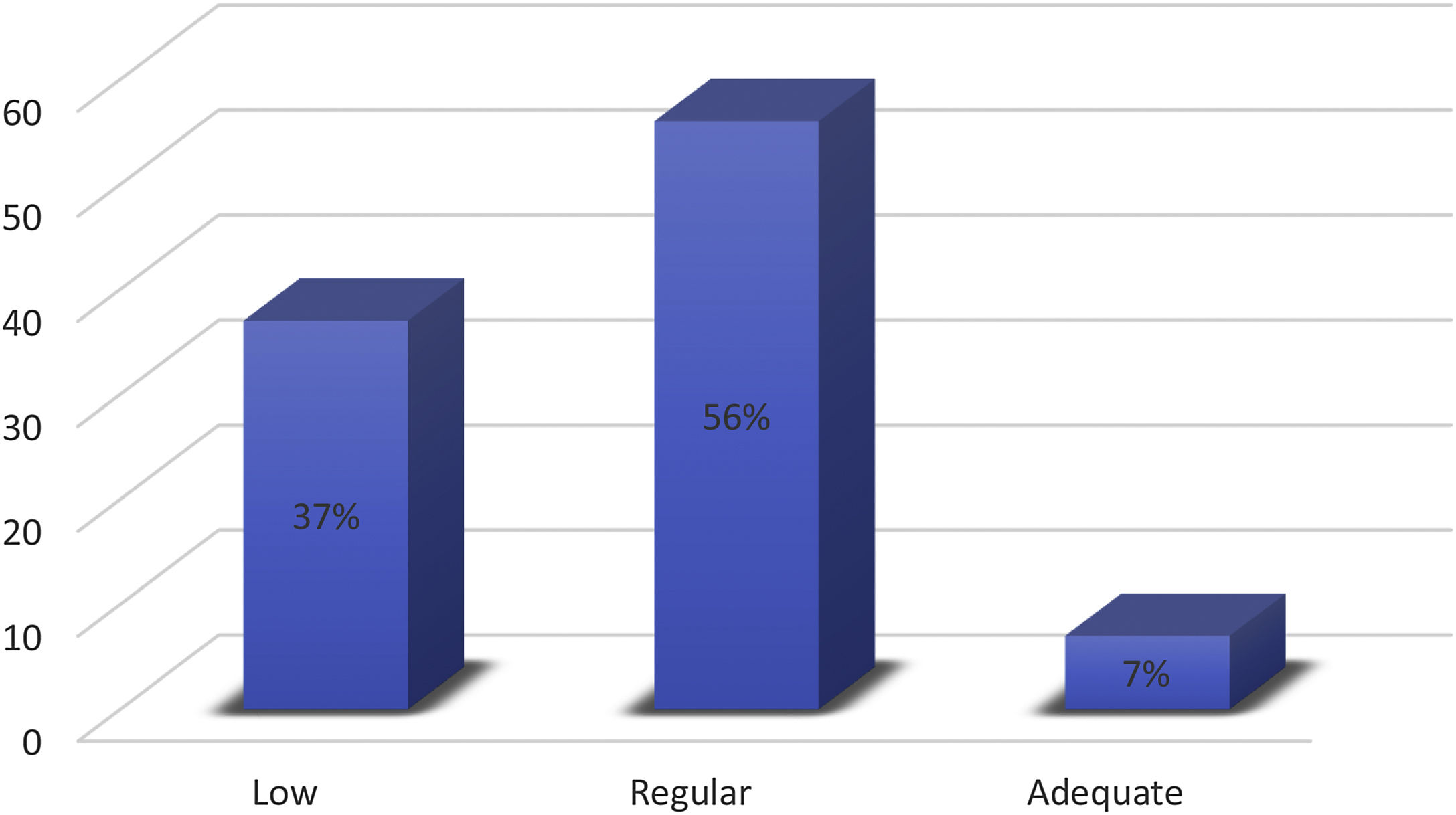

Fig. 1 shows the distribution according to diabetes knowledge where only 7% had an adequate level. The highest proportion of correct answers to the DKQ-24 questionnaire was observed in items 1 and 4 (basic knowledge of the disease), as well as items 9 and 12 (glycemia control, and diet and exercise). Items 17 and 23 (prevention of diabetic complications) showed the lowest score of adequate responses (data not shown).

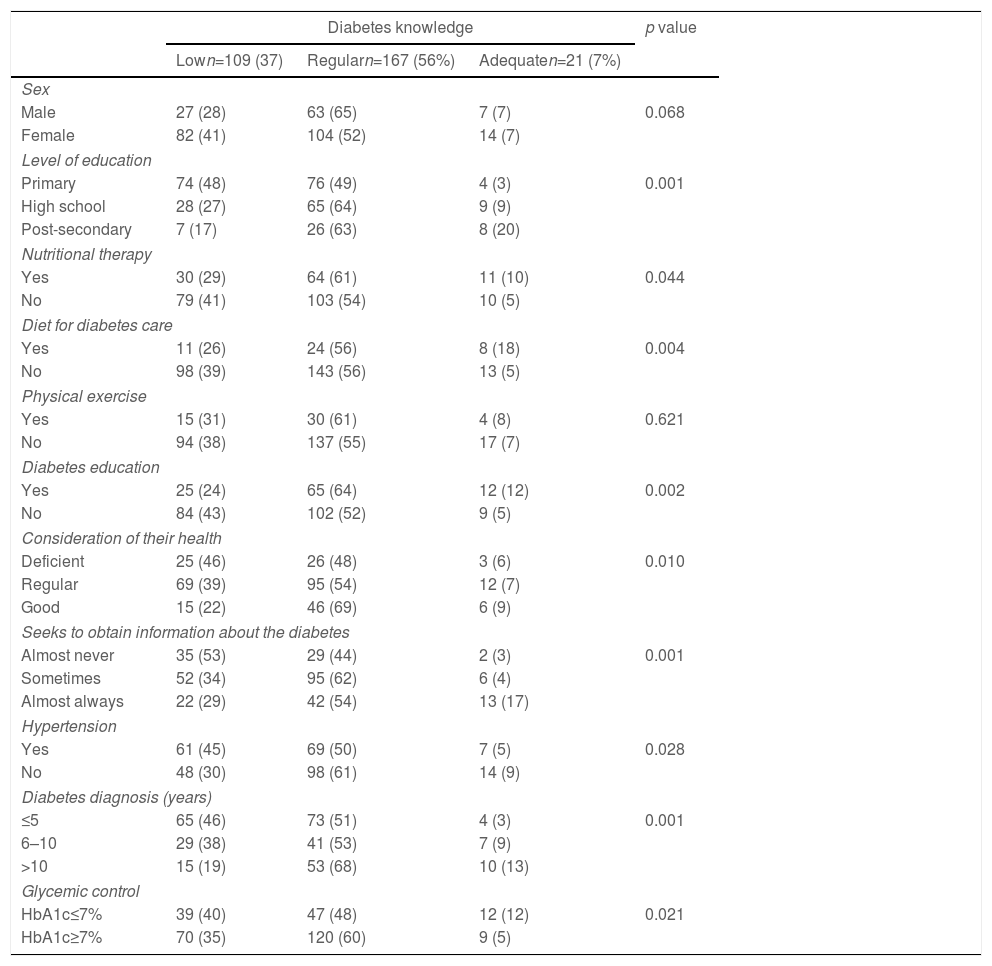

Diabetes knowledge related to the socio-demographic variables, lifestyle variables, adherence to treatment, and glycemia control are shown in Table 2. Patients with a high level of scholastic education had a higher proportion of adequate knowledge of diabetes (p=0.001). Likewise, patients who considered their health deficient (p=0.010), and those who almost never seek information about the illness (p=0.001), were associated with a low level of diabetes knowledge. Patients who received nutritional therapy, followed a diet, and had received previous diabetes education, had an adequate level of knowledge about their diabetes (p<0.05). The highest proportion of patients with HbA1c>7% was found in patients with regular knowledge of diabetes, (p=0.021).

Association of level of diabetes knowledge with socio-demographic, self-care, lifestyle and glycemic control variables, (n=297).

| Diabetes knowledge | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lown=109 (37) | Regularn=167 (56%) | Adequaten=21 (7%) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 27 (28) | 63 (65) | 7 (7) | 0.068 |

| Female | 82 (41) | 104 (52) | 14 (7) | |

| Level of education | ||||

| Primary | 74 (48) | 76 (49) | 4 (3) | 0.001 |

| High school | 28 (27) | 65 (64) | 9 (9) | |

| Post-secondary | 7 (17) | 26 (63) | 8 (20) | |

| Nutritional therapy | ||||

| Yes | 30 (29) | 64 (61) | 11 (10) | 0.044 |

| No | 79 (41) | 103 (54) | 10 (5) | |

| Diet for diabetes care | ||||

| Yes | 11 (26) | 24 (56) | 8 (18) | 0.004 |

| No | 98 (39) | 143 (56) | 13 (5) | |

| Physical exercise | ||||

| Yes | 15 (31) | 30 (61) | 4 (8) | 0.621 |

| No | 94 (38) | 137 (55) | 17 (7) | |

| Diabetes education | ||||

| Yes | 25 (24) | 65 (64) | 12 (12) | 0.002 |

| No | 84 (43) | 102 (52) | 9 (5) | |

| Consideration of their health | ||||

| Deficient | 25 (46) | 26 (48) | 3 (6) | 0.010 |

| Regular | 69 (39) | 95 (54) | 12 (7) | |

| Good | 15 (22) | 46 (69) | 6 (9) | |

| Seeks to obtain information about the diabetes | ||||

| Almost never | 35 (53) | 29 (44) | 2 (3) | 0.001 |

| Sometimes | 52 (34) | 95 (62) | 6 (4) | |

| Almost always | 22 (29) | 42 (54) | 13 (17) | |

| Hypertension | ||||

| Yes | 61 (45) | 69 (50) | 7 (5) | 0.028 |

| No | 48 (30) | 98 (61) | 14 (9) | |

| Diabetes diagnosis (years) | ||||

| ≤5 | 65 (46) | 73 (51) | 4 (3) | 0.001 |

| 6–10 | 29 (38) | 41 (53) | 7 (9) | |

| >10 | 15 (19) | 53 (68) | 10 (13) | |

| Glycemic control | ||||

| HbA1c≤7% | 39 (40) | 47 (48) | 12 (12) | 0.021 |

| HbA1c≥7% | 70 (35) | 120 (60) | 9 (5) | |

HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin; knowledge based on the DKQ-24 instrument used: 0–13 (low), 14–19 (regular), ≥20 (adequate).

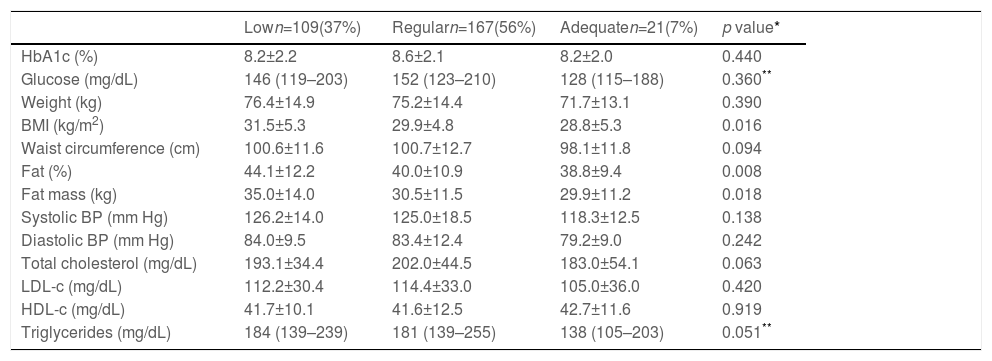

Having an adequate level of diabetes knowledge was associated with a lower BMI (p=0.016), lower fat percentage (p=0.008), and lower weight (p=0.018), as shown in Table 3.

Association between level of knowledge and the variables of metabolic control, (n=297).

| Lown=109(37%) | Regularn=167(56%) | Adequaten=21(7%) | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c (%) | 8.2±2.2 | 8.6±2.1 | 8.2±2.0 | 0.440 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 146 (119–203) | 152 (123–210) | 128 (115–188) | 0.360** |

| Weight (kg) | 76.4±14.9 | 75.2±14.4 | 71.7±13.1 | 0.390 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.5±5.3 | 29.9±4.8 | 28.8±5.3 | 0.016 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 100.6±11.6 | 100.7±12.7 | 98.1±11.8 | 0.094 |

| Fat (%) | 44.1±12.2 | 40.0±10.9 | 38.8±9.4 | 0.008 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 35.0±14.0 | 30.5±11.5 | 29.9±11.2 | 0.018 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 126.2±14.0 | 125.0±18.5 | 118.3±12.5 | 0.138 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 84.0±9.5 | 83.4±12.4 | 79.2±9.0 | 0.242 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 193.1±34.4 | 202.0±44.5 | 183.0±54.1 | 0.063 |

| LDL-c (mg/dL) | 112.2±30.4 | 114.4±33.0 | 105.0±36.0 | 0.420 |

| HDL-c (mg/dL) | 41.7±10.1 | 41.6±12.5 | 42.7±11.6 | 0.919 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 184 (139–239) | 181 (139–255) | 138 (105–203) | 0.051** |

HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin; BMI: body mass index.

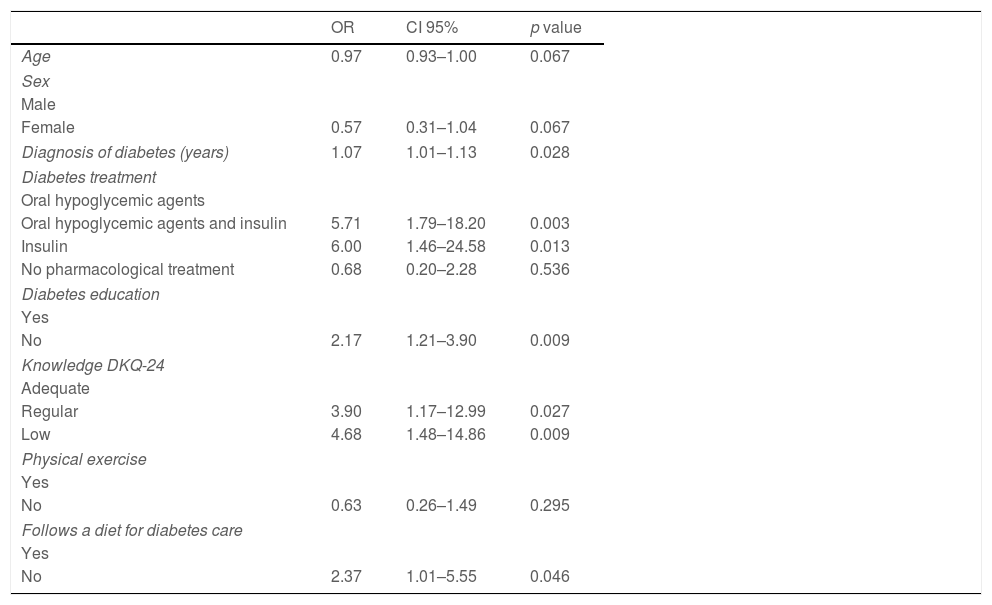

In the multivariate analysis as shown in Table 4, the risk of presenting with uncontrolled glycemia (HbA1c≥7%) is demonstrated when patients have a regular level of diabetes knowledge (OR: 3.90; CI 95%: 1.17–12.99; p=0.027). A low level of diabetes knowledge is associated with the presence of uncontrolled glycemia (OR: 4.68; CI:95% 1.48–14.86; p=0.009). Failing to follow a diet was associated with a two-times higher risk for uncontrolled glycemia (OR:2.37; CI 95%: 1. 01–5.5; p=0.046), similar to not having previous diabetic teaching (OR:2.17; CI 95%: 1.21–3.90; p=0.009). In patients who took oral hypoglycemics agents and insulin, or only insulin, there was an associated risk for uncontrolled glycemia (OR: 5.71; CI 95% 1.79–18.20; p=0.003; and, OR:6.00; CI 95% 1.46–24.58; p=0.013, respectively).

Logistic regression model to identify risk for uncontrolled HbA1c in level of knowledge with other socio-demographic and clinical variables, (n=297).

| OR | CI 95% | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.97 | 0.93–1.00 | 0.067 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | |||

| Female | 0.57 | 0.31–1.04 | 0.067 |

| Diagnosis of diabetes (years) | 1.07 | 1.01–1.13 | 0.028 |

| Diabetes treatment | |||

| Oral hypoglycemic agents | |||

| Oral hypoglycemic agents and insulin | 5.71 | 1.79–18.20 | 0.003 |

| Insulin | 6.00 | 1.46–24.58 | 0.013 |

| No pharmacological treatment | 0.68 | 0.20–2.28 | 0.536 |

| Diabetes education | |||

| Yes | |||

| No | 2.17 | 1.21–3.90 | 0.009 |

| Knowledge DKQ-24 | |||

| Adequate | |||

| Regular | 3.90 | 1.17–12.99 | 0.027 |

| Low | 4.68 | 1.48–14.86 | 0.009 |

| Physical exercise | |||

| Yes | |||

| No | 0.63 | 0.26–1.49 | 0.295 |

| Follows a diet for diabetes care | |||

| Yes | |||

| No | 2.37 | 1.01–5.55 | 0.046 |

HbA1c uncontrolled: ≥7% parameter of comparison. Classification category on the diabetes knowledge questionnaire: 0–13 (low), 14–19 (regular), ≥20 (adequate).

One of the main challenges for health care professionals is to achieve the goal of controlling diabetes. Unfortunately, lack of metabolic control persists in almost 68% of the population with diabetes in México.2 Behaviors that the patient exerts in self-care, monitoring, and modifying lifestyle, are crucial to achieving control of their illness. The results of the present study demonstrate that only 7% of the studied population have adequate knowledge about diabetes, which is lower than the 25% seen in the United States. The proportion of patients with diabetes who have low knowledge about the disease may vary from 7.3 to 82% in different countries around the world.10

The present study demonstrates that patients with a low or regular level of knowledge about diabetes had a higher risk for high levels of HbA1c. In addition, a higher proportion of patients with adequate levels of knowledge and HbA1c<7% was observed. These results coincide with those reported in the Pakistani population where knowledge of diabetes was associated with better HbA1c levels and self-care behaviors.9

Diabetes education was also found to be closely related to HbA1c levels and knowledge about diabetes. Structured diabetic education can have an impact on indicators of metabolic control, knowledge about the disease, and adopting appropriate behaviors to help control diabetes.28 While it has been identified that more knowledge about diabetes is associated with higher levels of formal education, better health conditions, and more perceived motivations, it has not been associated with better blood glucose levels, physical activity, or the abscence of chronic complications.29,30 Adding to that, the use of the Internet has been associated with more knowledge about diabetes, emphasizing the need to develop educational sites supported by healthcare professionals, and connecting patient–doctor interactions to provide nutritional therapy and monitor health care.31,32

The fact that a higher proportion of patients with adequate levels of diabetes knowledge had received nutritional therapy and followed a diet in caring for their disease, is consistent with reports by other authors.33 Also, we identified that HbA1c control is associated with patients who received diabetes education and followed a diet to care for their illness despite the proportion of these patients being low in the studied population and even when there is sufficient evidence of the efficacy of these measures focused on lifestyle modifications.6,34

The present study results show that patients with a low level of diabetes knowledge are those who perceive their health to be deficient and almost never try to obtain information about the illness. It has been reported that patients who perceive a greater threat to complications from diabetes are those who have a higher BMI, while those who perform physical activity perceive less risk of complications from the illness.35

As previously mentioned, the relationship between level of knowledge and metabolic control is controversial: in diabetic patients, it has been reported that a low level of health literacy about the disease is associated with more uncontrolled glycemia, which is consistent with our findings.36 Among the strengths of the present study is the identification of the level of diabetes knowledge as low or regular, as well as its association with poor control of glycemia. Likewise, other variables that could be associated with the level of knowledge and glycemia control were identified, such as the level of education, years since diagnosis with the diabetes, and receiving diabetes education and a diet, which are important components in the integral treatment of the illness.

One of the limitations of this study is its cross-sectional nature and the sample size of patients studied. Future studies with larger sample sizes should be performed in order to confirm associations by adjusting for other variables. The level of diabetes knowledge and overall health literacy regarding diabetes need to be measured, which have been reported as associated with control of glycemia and self-care in diabetic patients: health literacy continues to be low, even in more developed countries and those with better health services.10,37 It is important that diabetes education be adjusted to the variables such as level of education, years since diagnosis with the disease, prior knowledge, and self-care conduct, particularly in public healthcare settings with high demand and a lack of human resources and healthcare infrastructure.

ConclusionLow or regular diabetes knowledge is associated with poor glycemia control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Patients with a low level of diabetes knowledge also had low educational levels, an absence of nutritional therapy, and did not follow a diet to care for their diabetes.

- •

The relationship between level of knowledge and glycemic control of the disease is controversial. Diabetes education recommended to improve metabolic control of the disease.

- •

Better knowledge about the disease was associated with improved glycosylated hemoglobin.

- •

In patients who received diabetes education it was associated with better metabolic control.

- •

Those patients with adherence to a diabetes diet had better glycemic control.

This study was approved by an ethics and research committee of the Mexican Institute of Social Security, in Mexico City, Mexico.

FinancingThe authors acknowledge the financial support provided by the Sectoral Fund for Research in Health and Social Security of the National Council of Science and Technology. Identification number: 2012-01-18101.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank the authorities of the participating clinics for access to the facilities granted to carry out this study.