Identify externalizing and internalizing behaviors in high school adolescents in three schools in a northern border city in Mexico and their type of family.

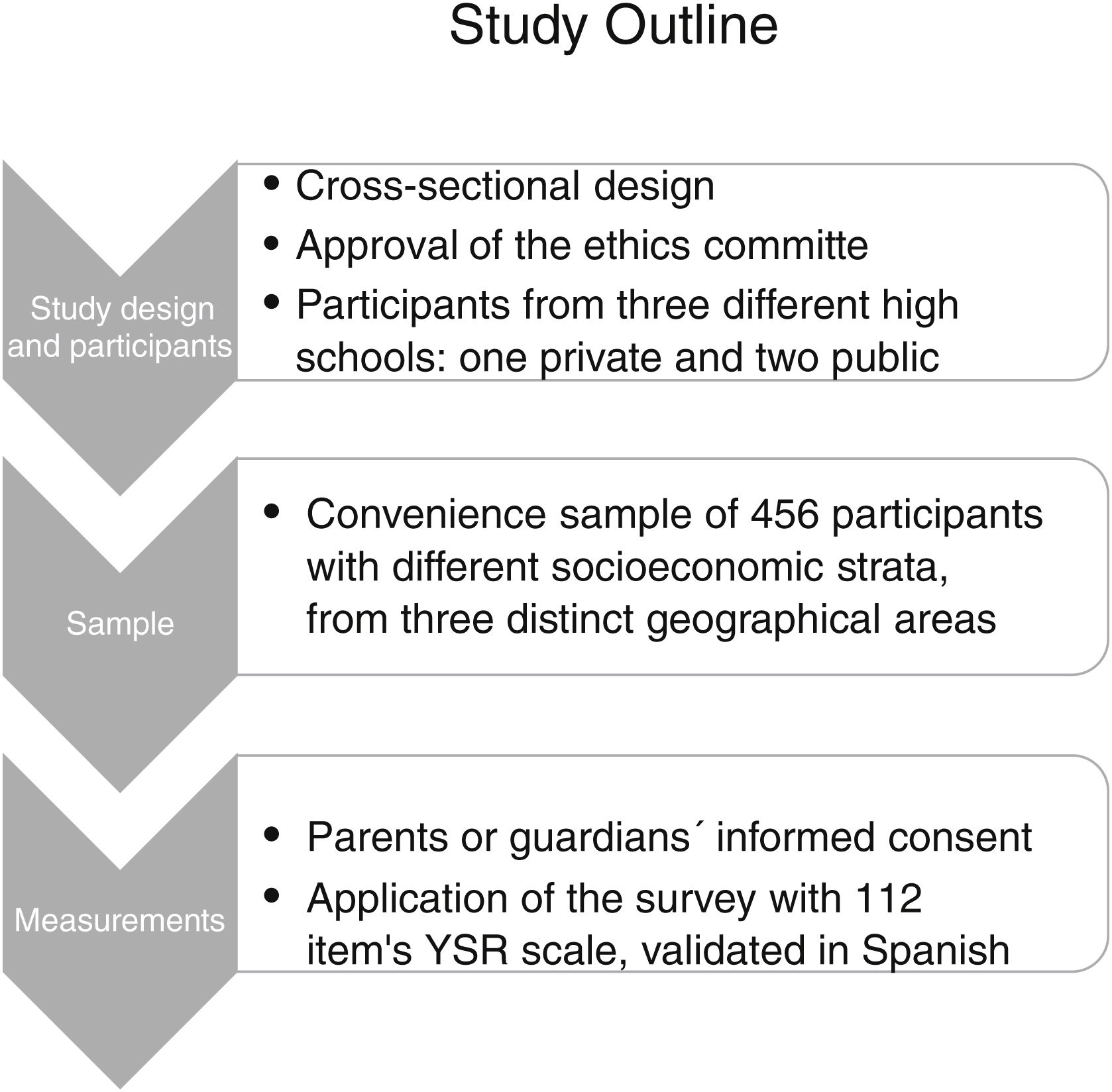

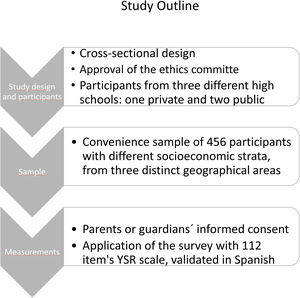

DesignCross-sectional survey.

LocationThree schools in the city of Tijuana, Mexico: two public and one private.

Participants454 baccalaureate students 14–19 years old.

Main measurementsWe utilized Youth Self Report Scale, adapted and validated in Spanish, that measure internalization behaviors (anxiety, depression, isolation or somatic complaints), and externalization behaviors (verbal aggressiveness, delinquent behavior and attention-seeking). For dichotomous discrimination between deviant and nondeviant scores, we use the borderline clinical range by classifying YSR scale's T scores≥60, and to analyze the relationship between behavior problems or competencies and living or not in a nuclear family we utilized multiple logistic regression.

Results55% were female, mean age 16.4 years±0.98, and 62.3% came from a nuclear family. Prevalence of internalizing behaviors was 15.6%, and externalizing behaviors 14.8%. Women had statistically higher mean scores in depressive, anxious and verbally aggressive behavior, somatic complaints, and thought problems. The prevalence of internalizing behaviors in adolescents with nuclear family was 11.7% (n=33), and for adolescents with another type of family was 22.2% (n=38), OR 2.17 (CI 95% 1.30–3.61, p=0.003), but no differences was observed for externalizing behaviors and family type. When adjusted for sex, age, and public or private school, internalizing behaviors and specifically depressive behavior remained significant.

ConclusionsWe detected a moderate prevalence of internalizing behaviors in Mexican adolescents, predominantly among women, and also observed that not living with a nuclear family increases the odds of presenting internalizing behaviors. It is important that parents, teachers, and healthcare workers remain vigilant to detect these problems in a timely manner and develop interventions to improve the mental health and well-being of adolescents.

Identificar conductas internalizantes y externalizantes en adolescentes de escuelas preparatorias en una ciudad fronteriza al norte de México y su tipo de familia.

DiseñoEncuesta transversal.

EmplazamientoTres escuelas de la ciudad de Tijuana, México: dos públicas y una privada.

Participantes454 estudiantes de preparatoria de 14-19 años de edad.

Principales medicionesSe utilizó la escala Youth Self Report validada al español, que mide conductas internalizantes (ansiedad, depresión, aislamiento y quejas somáticas) y externalizantes (agresión verbal, conducta delictiva y búsqueda de atención). Para la discriminación dicotómica entre puntajes desviados y no desviados, usamos el rango clínico límite al clasificar los T scores de ≥ 60 de la escala YSR, y para analizar la relación entre problemas de comportamiento o competencias y vivir o no en una familia nuclear utilizamos regresión logística múltiple.

ResultadosEl 55% eran mujeres, la media de edad fue de 16.4 años±0.98, y el 62.3% procedían de familias nucleares. La prevalencia de conductas internalizantes fue de 15.6% y de conductas externalizantes de 14.8%. Las mujeres tenían puntuaciones medias estadísticamente más altas en conducta depresiva, ansiosa y verbalmente agresiva, quejas somáticas y problemas de pensamiento. La prevalencia de conductas internalizantes en adolescentes con familia nuclear fue de 11.7% (n=33), y para adolescentes con otro tipo de familia fue de 22.2% (n=38), OR 2.17 (IC 95% 1.30-3.61, p=0.003), pero no se observaron diferencias para conductas externalizantes y tipo de familia. Al ajustar por sexo, edad y escuela pública o privada, las conductas internalizantes y específicamente la conducta depresiva se mantuvieron significativas.

ConclusionesDetectamos una prevalencia moderada de conductas internalizantes en adolescentes mexicanos, predominantemente entre las mujeres, y también observamos que no vivir con una familia nuclear aumenta las probabilidades de presentar conductas internalizantes. Es importante que los padres, maestros y trabajadores de la salud permanezcan atentos para detectar estos problemas de manera oportuna y desarrollar intervenciones para mejorar la salud mental y el bienestar de los adolescentes.

Adolescence is accompanied by accelerated physical, psychological, and social changes; it begins with puberty and ends around the second decade of life, when physical growth and development are complete, and psychosocial maturity is reached. The World Health Organization (WHO) considers “adolescence” between 10 and 19 years of age, a very important age group from a public health perspective, given that an adolescent's state of health, behavior, and habits have an enormous impact on their future health and lifestyle.1

According to data from the Pan American Health Organization of the 20 leading causes of Years Lived with Disability in adolescents and pre-adolescents aged 10–14 in the Americas, anxiety disorders are the second leading cause and depression the fifth. For adolescents aged 15–19, depression is the leading cause, followed by anxiety disorder, and in fifth place we find psychological disorders caused by drug use.2 Something similar is observed in Mexico, where the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI)3 reports the incidence of use of illegal substances among adolescents aged 12–17 increased significantly between 2011 and 2016, from 2.9% to 6.2%, respectively. In 2022 INEGI reports accidents as the leading cause of death in adolescence, followed by malignant tumors, and in third position self-inflicted harm suicide.4

In the mid-1980s many specialists working with minors expressed concern that the classification system found in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) did not adequately address clinically troubling disorders of behavioral development. This drove several studies aimed at improving the classification, and after years of study a system was proposed that suggested empirical measurement of certain behavioral dimensions: the Behavioral Dimensions and the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA).5 The ASEBA offers forms useful for screening (though not diagnostic) with helpful ratings for parents and teachers, which contain a checklist of child behaviors to be classified in two primary syndromes. The first includes internalization problems, which are related to over-controlling behavior, and the second, externalization problems, related to out-of-control behaviors. Internalizing behaviors include anxiety, depression, somatization, and social withdrawal, whereas externalizing behaviors include delinquent behavior, aggression (verbal or physical), and hyperactivity.6

The primary risk factors associated with the presence of externalizing or internalizing behaviors in adolescents that have been studied the most are: parenting styles,7 emotional state of parents, stress, exhaustion, and depression,8,9 family structure,10,11 genetic predisposition, peer influence, refusal assertiveness, emotional instability, and association with friends which have antisocial behaviors.12,13

Physical, verbal, and cyber bullying among adolescents also has a documented link to suicidal ideation and behavior.14 Victims of peer bullying have not only an increased risk of suicidal ideation or internalizing behavior, such as anxiety or depression, but also are more likely to develop behaviors which put their health at risk, and in some cases externalizing behaviors are observed, such as physical or verbal aggressiveness.15

Though it has been proven that poor parenting during psychological and social development, and exposure to an adverse environment predict problematic, antisocial adolescents with a greater incidence of behavioral disorders,16 the same behaviors are observed in adolescents who have not been exposed to these factors. The difference between these two groups is that the second group develop defiant and antisocial behaviors which disappear at the end of adolescence. The behavioral justification in this group conforms to the needs of autonomy, identity, and peer acceptance, and the behaviors disappear on maturity associated with adult responsibility.17

With respect to the educational system in Mexico, education is considered obligatory and is made up of four levels, the preschool that includes 1–3 years, the primary with six, the secondary with three and finally the high school or baccalaureate with three school years (university education is not compulsory). The school attendance of the Mexican population has been increasing over the years, being in the case of primary school, very close to 100% in children from 6 to 11 years old, while a quarter of Mexican youth do not attend to high school.18 According to data from a national survey of the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), of the enrolled students from 3 to 29 years old, 89.7% completed the school year 2021–2022 in public schools and 10.3% in private schools, while, in higher education, the population enrolled in private schools was higher than the rest of the educational levels (25.6%).19 In this sense, it is important to highlight that Mexican families tend to consider that private schools have a higher educational quality and offer more specialized study programs focused on the comprehensive education of students, which makes them a more attractive option. Hence, they are willing to finance all the expenses that comprise the school trajectory of their children, regardless of the high costs and in many cases sacrificing their family finances.

For all of the aforementioned, the objective of this study was to identify externalizing and internalizing behaviors in adolescent students and their family structure in public and private high schools in a border city in the northern part of Mexico.

Material and methodsDesign, population and study settingsA cross-sectional survey was carried out in the year of 2019, in high school adolescents from the city of Tijuana, which is the largest city in the state of Baja California, Mexico, situated on the U.S. border adjacent to San Ysidro, California. Tijuana is one of Mexico's fastest-growing cities, and according to the most recent 2020 census, it has two million inhabitants, of which 4.1% were born in the United States, and 44.3% outside the state.20 The Tijuana-San Ysidro border crossing has become one of the busiest in the world, with almost three million people crossing each month in 2022.21

The study population was obtained from three high schools, two of which were public, one had about 5000 enrolled students and the other with approximately 600. The third school was private and had 150 students enrolled. From this population, a convenience sample of 460 students was obtained, which consisted of 159, 169, and 126 participants respectively. That sample included students from various social strata, with a minimum age of 14 years old and a maximum of 19, within grades 11–13.

MeasurementsTo identify externalizing and internalizing behaviors we used the Youth Self Report (YSR) DSM-oriented scales, which is part of the ASEBA scales,5 adapted and validated in Spanish.22 This scale uses the primary diagnostic categories of the DSM-IV: affective disorders, anxiety disorders, somatization, attention disorders, hyperactivity, defiant-oppositional disorder, and other behavior disorders. More than diagnostic, this scale aims to quickly and efficiently assess various aspects of adaptive behavioral functioning of adolescents between 11 and 18 years of age, from multiple perspectives: parents, caregivers, teachers, observers, and clinical interviewers. The scale consists of 112 items, with three response options each on the Likert scale with the following scores: 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), and 2 (very true, or often true). The subscales problems are grouped in turn as internalizing or externalizing, the former including depression (9 items), anxiety (4 items), isolation (4 items) and somatization (5 items); and the latter comprising verbal aggressiveness (6 items), attention-seeking behavior (4 items), and delinquent behavior (7 items).22

With respect to demographics, we considered sex and age of participant, as well as their academic year. With regards to family, we asked with whom they lived, as well as the education level and occupation of the father, mother, or guardian. Families were then classified as one of the following: 1. Nuclear: comprised of father, mother, and children; 2. Extended: nuclear family plus some other members (grandparents, aunts, uncles, etc.); 3. Single parent with mother or father: if they live with only the mother or father; 4. Compound: if they live with non-relatives (friends or guardians); 5. Reconstituted or stepfamily: if they live with step-parents; 6. Collateral: if they live only with grandparents, aunts, uncles, or siblings; and 7. Unipersonal: if they live alone.

Before application of the scale in the student population, we implemented a pilot with 102 participants, with the goal of proving the reliability of the instrument. The pilot study found a Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient of 0.924.

Statistical analysisFor analysis of the categorical variables such as subject sex, family type, and parent occupation, we determined the frequency and percentage. To compare scores between men and women we calculated Mean differences of raw scores with Student's t-test. To interpret the scores of the problems measured by the YSR scale, we use the cut points recommended by the ASEBA School-Age Forms Manual,5 which says that for efficient dichotomous discrimination between deviant and nondeviant scores, use the borderline clinical range by classifying T scores≥60 as deviant on Internalizing, Externalizing, and Total Problems scales, for that reason, we proceeded to transform the YSR raw scores into T scores. Finally, the relationship between behavior problems or competencies and living or not in a nuclear family was estimated using multiple logistic regression. The results are presented as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals. Said analysis was performed using the statistical software package SPSS, version 21.

Ethical considerationsOnce the research protocol was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the School of Medicine (reference number: 386/2019-1), the participants were asked for their informed consent, explaining the objective of the study, the confidential nature of the information, the possibility of leaving the study at any time without any kind of negative consequences, and that they would not receive remuneration for their participation. Those who accepted were asked to bring their parents or guardians’ informed consent with the corresponding signature, guaranteeing in the same way that participation would be voluntary, and emphasizing that in no way would mental, moral, or academic stability be infringed on their child. And if it was considered necessary, he or she could request support at the facilities of the University Center for Psychological Care and Research (CUAPI).

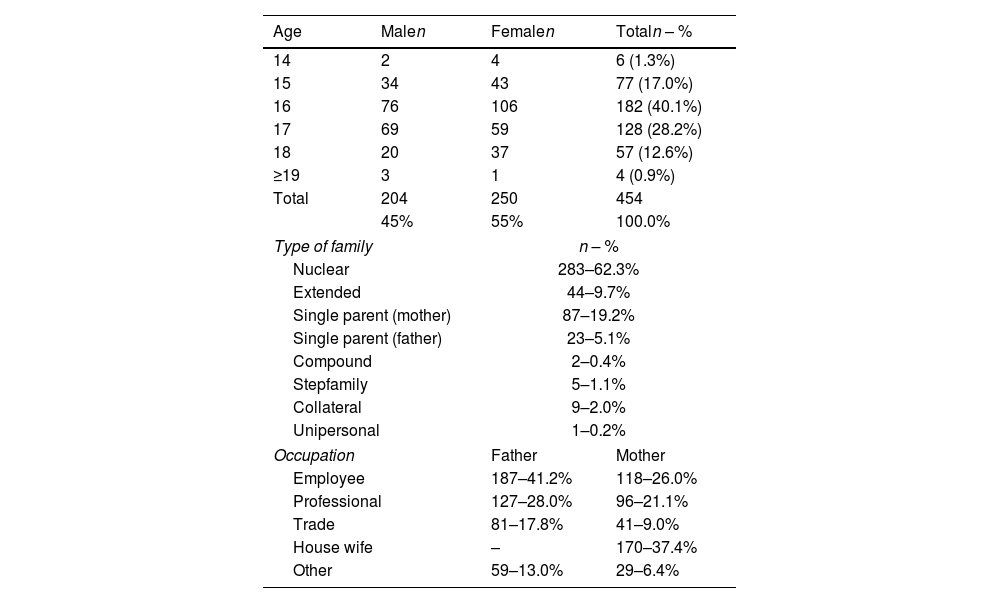

ResultsAfter removing six respondents for incomplete data, we were able to analyze a total sample of 454 students from different semesters in three high schools. 45% of participants were male, 55% female, with an age range of 14–20 years old (mean age 16.37 years±0.99). 76.7% of participants were born in Tijuana, 8.6% in the United States, and the remaining 14.8% in other states in Mexico. The “nuclear” family was the most prevalent type (62.3%), followed by the “single parent–mother” type (19.2%). The majority of the parents, both mothers and fathers, were employees of some company or institution. 28.0% of fathers and 21.1% of mothers had a professional degree (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the baccalaureate students participants.

| Age | Malen | Femalen | Totaln – % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 2 | 4 | 6 (1.3%) |

| 15 | 34 | 43 | 77 (17.0%) |

| 16 | 76 | 106 | 182 (40.1%) |

| 17 | 69 | 59 | 128 (28.2%) |

| 18 | 20 | 37 | 57 (12.6%) |

| ≥19 | 3 | 1 | 4 (0.9%) |

| Total | 204 | 250 | 454 |

| 45% | 55% | 100.0% | |

| Type of family | n – % | ||

| Nuclear | 283–62.3% | ||

| Extended | 44–9.7% | ||

| Single parent (mother) | 87–19.2% | ||

| Single parent (father) | 23–5.1% | ||

| Compound | 2–0.4% | ||

| Stepfamily | 5–1.1% | ||

| Collateral | 9–2.0% | ||

| Unipersonal | 1–0.2% | ||

| Occupation | Father | Mother | |

| Employee | 187–41.2% | 118–26.0% | |

| Professional | 127–28.0% | 96–21.1% | |

| Trade | 81–17.8% | 41–9.0% | |

| House wife | – | 170–37.4% | |

| Other | 59–13.0% | 29–6.4% | |

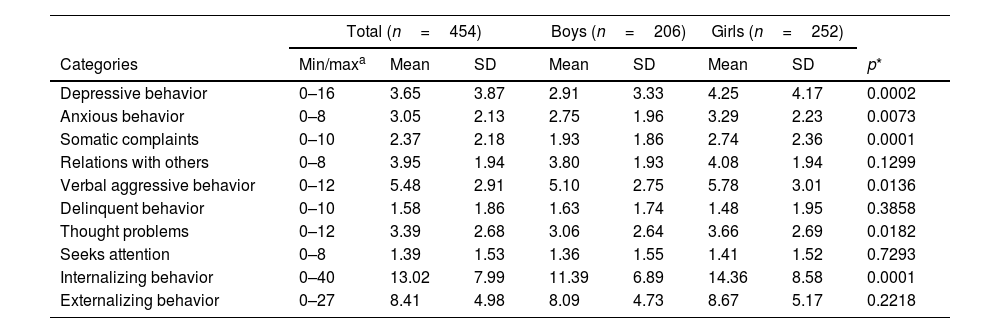

In Table 2, we can see a comparison of the raw scores mean behavioral characteristics observed between men and women, along with their respective standard deviations and p values using Student's t-test, and we found statistically significant differences, with higher mean scores for women than men, with respect to depressive behavior, somatic complaints, anxious and verbally aggressive behavior, and thought problems. Women also showed a higher score with regards to internalization behaviors when compared to men. Likewise, when specifically asking about suicidal ideation, 11.6% (n=53) of the participants responded the answer options 1 or 2. Answer option 1 (somewhat or sometimes true): 8.4% [n=38], and answer option 2 (very true or often true): 3.3% [n=15]. No differences were observed between the sexes.

Total and sex stratified mean of raw scores for each YSR subscale.

| Total (n=454) | Boys (n=206) | Girls (n=252) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | Min/maxa | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p* |

| Depressive behavior | 0–16 | 3.65 | 3.87 | 2.91 | 3.33 | 4.25 | 4.17 | 0.0002 |

| Anxious behavior | 0–8 | 3.05 | 2.13 | 2.75 | 1.96 | 3.29 | 2.23 | 0.0073 |

| Somatic complaints | 0–10 | 2.37 | 2.18 | 1.93 | 1.86 | 2.74 | 2.36 | 0.0001 |

| Relations with others | 0–8 | 3.95 | 1.94 | 3.80 | 1.93 | 4.08 | 1.94 | 0.1299 |

| Verbal aggressive behavior | 0–12 | 5.48 | 2.91 | 5.10 | 2.75 | 5.78 | 3.01 | 0.0136 |

| Delinquent behavior | 0–10 | 1.58 | 1.86 | 1.63 | 1.74 | 1.48 | 1.95 | 0.3858 |

| Thought problems | 0–12 | 3.39 | 2.68 | 3.06 | 2.64 | 3.66 | 2.69 | 0.0182 |

| Seeks attention | 0–8 | 1.39 | 1.53 | 1.36 | 1.55 | 1.41 | 1.52 | 0.7293 |

| Internalizing behavior | 0–40 | 13.02 | 7.99 | 11.39 | 6.89 | 14.36 | 8.58 | 0.0001 |

| Externalizing behavior | 0–27 | 8.41 | 4.98 | 8.09 | 4.73 | 8.67 | 5.17 | 0.2218 |

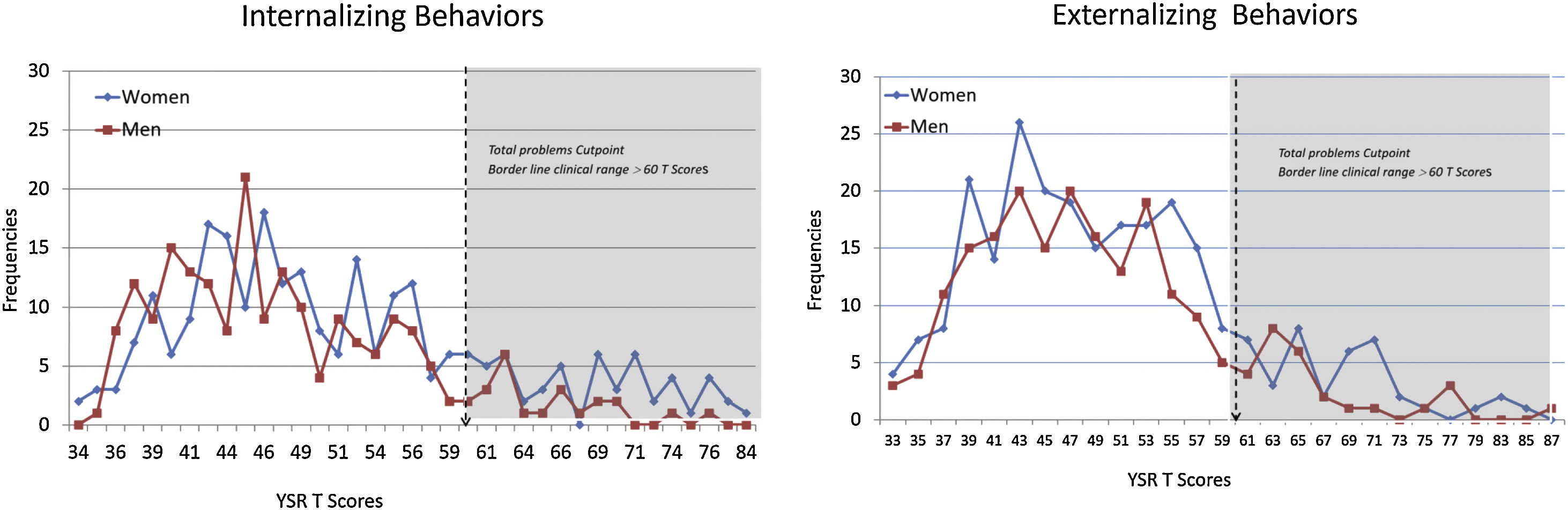

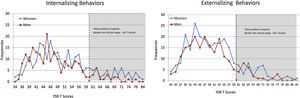

In Fig. 1, we can see the standardized T scores frequencies of internalizing and externalizing behaviors between male and female adolescents and the problems cutpoint at 60 to discriminate deviant and no deviant scores.

The prevalence of internalization behaviors identified in the entire study population was 15.6% (n=71/454), 20.0% (n=50/250) in women, and 10.3% in men (n=21/204), OR of 2.18 (CI 95% 1.26–3.77), p=0.005. About the externalizing behavior, the total prevalence was 14.8% (n=67/454), 16.0% (n=40/250) in women, and 13.2% (n=27/204) in men, but no statistical differences were observed.

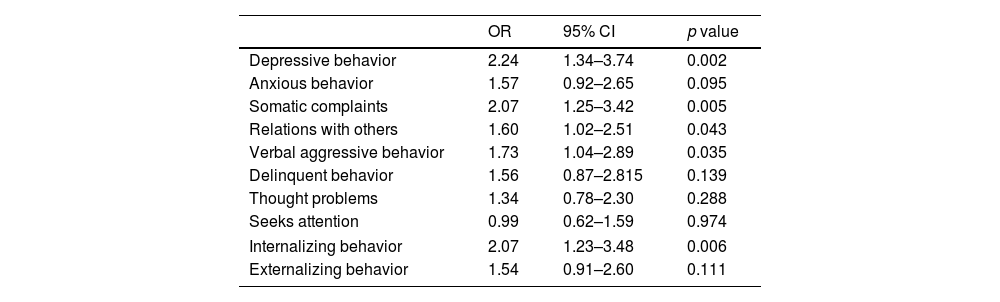

When analyzing by the participant's family type, we found that not belonging to a nuclear family increase the odds of presenting internalizing behaviors. The prevalence of internalizing behaviors in participants with nuclear family was of 11.7% (n=33), and for participants with no nuclear family was 22.2% (n=38), OR 2.17 (CI 95% 1.30–3.61, p=0.003). After adjusting for sex, age, and public or private school, there was a statistically significant increase in the odds for internalizing behavior, which involved depressive behaviors, somatic complaints, relations with others, and verbal aggressive behavior in adolescents not living in nuclear families compared to those living with another type of family (Table 3).

Results of multiple logistic regression models (one for each YSR's subscales) for the association of living or not in a nuclear family of 454 high school adolescents in a northern border city of Mexico.

| OR | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depressive behavior | 2.24 | 1.34–3.74 | 0.002 |

| Anxious behavior | 1.57 | 0.92–2.65 | 0.095 |

| Somatic complaints | 2.07 | 1.25–3.42 | 0.005 |

| Relations with others | 1.60 | 1.02–2.51 | 0.043 |

| Verbal aggressive behavior | 1.73 | 1.04–2.89 | 0.035 |

| Delinquent behavior | 1.56 | 0.87–2.815 | 0.139 |

| Thought problems | 1.34 | 0.78–2.30 | 0.288 |

| Seeks attention | 0.99 | 0.62–1.59 | 0.974 |

| Internalizing behavior | 2.07 | 1.23–3.48 | 0.006 |

| Externalizing behavior | 1.54 | 0.91–2.60 | 0.111 |

Adjusted by sex, age and private or public school. All values were rounded to two digits, except for p-values.

OR: odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

Finally, 35% (n=161) of the students reported having seen a psychologist at least once. The most common reason for seeing the psychologist was emotional problems, followed by behavioral and family problems.

DiscussionThe prevalence of internalizing behaviors identified in this study was slightly higher than a population survey carried out in Germany23 that observed 7.9%, or lower than another Spanish research24 that reported that 20.6% had exceeded the thresholds cut-off points in psychological problems. But when our results compared the prevalence by sex, it was girls who showed significantly higher scores than boys, similar to what was observed in another study carried out in the countries of Canada, the Netherlands, and the UK,25 which reported a prevalence of 18% in the general female adolescent population and 40% in suicidality in transgender adolescents, while in men it was 7% and 18%, respectively. Regarding externalizing behaviors, our research identified a slightly higher prevalence than in the same German population survey.23 Also, when comparing the mean of raw scores of internalizing behaviors of Mexican adolescents with another study that reported the scores of the US and Spanish adolescents, we observed that the mean of raw scores identified in Mexico was similar to the US and slightly lower than the Spanish adolescents. As for externalizing behaviors, it was similar for girls and a bit lower for Mexican boys.26

Other studies have verified that women indeed tend to have more internalizing behaviors such as depression, somatic complaints, and anxiety in a ratio of 2 to 1 with respect to men. However, they also report that age is the strongest predictor, since depressive symptoms in women increase in early adolescence and then decrease, while in the case of men it operates inversely, that is, it tends to rise in late adolescence.27–29

With regard to externalizing behaviors, the scores for the female and male population did not show marked differences, with the exception of verbal aggressiveness in women. As corroborated by Martínez Martínez et al.,29 women tend to have higher levels of verbal aggression and men of physical or overt aggression. In this sense, it should be noted that women are usually more expressive, eloquent, and predominantly use oral language as a means of communication to persuade and even discuss, compared to men who use more direct and corporal confrontation, among other reasons, due to social norms and established reinforcers.

The World Health Organization associates depression with other behaviors that put at risk the health and life of individuals who suffer from it and mentions that adolescence is a period of particularly high vulnerability for the development of both psychopathologies and suicidal behavior.30 It further correlates these disorders to abrupt changes related to greater autonomy, belonging to a group, exploration of sexual identity, greater access and use of technology, as well as exposure to any form of interpersonal violence and a history of mental or substance abuse. In addition to the above, other study31 postulates that the specific risk factors identified in women were being victims of violence in intimate relationships, loneliness, rejection, and guilt; while for men it was pressure from peers or cyber acquaintances, and parents that were separated or divorced.

The data on suicidal ideation obtained in this study reveal that 11.6% of those surveyed stated that it was “true” or “very true” to have thoughts of this nature, which is close to what has been reported by other studies. In a sample of Mexican adolescents between the ages of 12 and 15, it was found that 8.1% had experienced suicidal ideation,32 while in Polish adolescents between 13 and 19 years of age, it was found that 25% had suicidal ideation, 16% had plans, and 4.4% had attempted.33 When we compared suicidal thinking by sex in our research, no statistical differences were found. In contrast, other studies, including a systematic review that analyzed 67 investigations, point out that suicidal ideation and attempts are more prevalent in women than in men and that women have almost double the risk for suicide attempts, but men almost triple the risk of death by suicide.31,33

When analyzing whether the characteristics of the adolescents’ families were associated with the probability of presenting certain internalizing behaviors, we found that not belonging to a nuclear family increase the odds of internalizing behaviors and specifically depressive behavior. Although, another study34 discussed the importance of the family climate more than the type of family, since adolescents with greater family cohesion were less likely to report a deficit in their health and satisfaction with life, even though those who lived with single-parent families or with divorced parents showed slightly lower life satisfaction and more problem behaviors. While another research35 has shown that having the biological father live elsewhere predicts greater internalizing symptoms, our results did not show any statistically significant differences in behavior problems with living only with the father or with the mother. Nevertheless, another study observed that paternal imposition and maternal psychological control may predict internalizing problems, and inconsistent discipline, may predict externalized conflicts.36

With respect to Mexico, in recent years, this country has been immersed in a period of strong structural violence, high human mobility, and weakening of institutions, with low expectations for the younger generations, which has caused youth to be easy prey for criminal groups and participant in antisocial behavior. Violence is not specifically a problem of the poor or marginalized social classes, but it does respond to specific realities linked to the deterioration of living conditions and social imbalance, family disintegration, consumerism, and low expectations regarding the future of adolescents and young people who drop out of formal education due to the lack of affective and economic support and attention to their dreams, coupled with intrafamily violence.37

Some of the limitations of this research that we could mention is its cross-sectional nature and the fact that a probabilistic sample was not obtained. However, we believe that one of its strengths was having obtained a representative sample from selected local high schools from both the public and private sectors (two of them with student populations from various sociodemographic strata). In addition, the instrument used was a fairly well accepted scale by both teachers and psychologists that has already been adapted and validated in the Spanish-speaking population. Despite the aforementioned limitations, the YSR scale does not offer a precise diagnosis, but it does offer a more differentiated image of the socio-emotional situation of Mexican adolescents. The interpretation of these results may not be generalizable and needs to be replicated in other populations. For future research, we suggest being consistent when interpreting the scores of the YSR subscales, so that they can be more easily compared, since some research only analyzes the means of raw scores, others the prevalence of two of the response options, being that this scale suggests cut-off points to be interpreted, and it would be important for these cut-off points to be validated in different populations and regions.

ConclusionsThe categorization of personality traits in two dimensions (internalizing and externalizing) explains most of the associations between personality patterns, which may be indicators of psychopathology or clinical dysfunction, without forgetting that this bifactorial model of personality is on the rise due to its theoretical value and its usefulness. Regardless of whether the adolescent lives with the mother or the father, the vulnerability exposed here, at least emphasizes the importance of the role played by both in the emotional balance of their children.

No matter how much society is familiar with the terms depression and anxiety, the truth is that the symptoms often go unnoticed by parents and teachers who can minimize their fatal consequences,38 because they consider them something normal and temporary, typical of “teenagers,” or else because they lack the tools to deal with the complex situation. It is therefore of vital importance that data from research such as ours be used to design timely interventions aimed at improving the mental health and well-being of the adolescent population.

- •

Depression holds third place in world-wide morbidity among adolescents, closely associated with the third-leading cause of death, which is suicide in this age group. Depression and anxiety symptoms often go unnoticed by parents and teachers who can minimize their fatal consequences.

- •

This article shows an overview of the mental health of Mexican adolescents through a simple way of carrying out the monitoring of certain components and classifies them into two behavioral dimensions that, although they are not diagnostic, can guide parents and teachers to implement community measures aimed at improving the mental health and well-being of the adolescent population.

- 1.

Has your work involved animal experimentation?: No

- 2.

Does your work involve patients or human subjects?: YesIf the answer is affirmative, please mention the ethics committee that approved the research and the registration number: Bioethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine and Psychology of the Autonomous University of Baja California, with registration number 386/2019-1.If the answer is yes, please confirm that the authors have complied with the rules ethics relevant to publication: YesIf the answer is affirmative, please confirm that the authors have the informed consent of the patients: Yes

- 3.

Does your work include a clinical trial?: No

- 4.

Are all the data shown in the figures and tables included in the manuscript included in the results and conclusions section?: Yes

None.

Conflict of interestThe authors report no conflicts of interest.

Thanks to CONACYT for the scholarship awarded to the first author.