To determine the prevalence and associated factors of female genital mutilation (FGM) among daughters of women aged 15–49 in Somalia using data from the 2020 Somaliland Demographic and Health Survey (SDHS).

DesignA cross-sectional study utilizing data from the 2020 SDHS.

SettingData was collected across Somalia, including urban, rural, and nomadic areas.

Main measurementsFGM prevalence was presented as percentages. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify associated factors, presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

ResultsThe prevalence of FGM among daughters was 24%. Factors significantly associated with FGM included age, region, residence, education, and wealth index. Younger daughters were more likely to be circumcised (p=0.000, 95% CI: 0.066–0.274). Rural residence increased the likelihood of FGM (OR=1.436, CI=1.257–1.64). Primary education increased the odds of FGM (OR=1.334, CI=1.127–1.58). Mothers who believed FGM should continue were more likely to have circumcised daughters (OR=1.464, CI=1.305–1.642).

ConclusionsFGM prevalence among daughters in Somalia is influenced by age, region, rural residency, and education. The findings highlight the need for targeted educational and intervention programs, particularly in rural areas, to effectively reduce FGM practices.

Determinar la prevalencia y los factores asociados de la mutilación genital femenina (MGF) entre las hijas de mujeres de 15 a 49años en Somalia utilizando datos de la Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud de Somalia de 2020.

DiseñoEstudio transversal que utiliza datos de la Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud de Somalia de 2020.

EntornoLos datos se recopilaron en toda Somalia, incluidas las zonas urbanas, rurales y nómadas.

Mediciones principalesLa prevalencia de la MGF se presentó en porcentajes. Se utilizó un análisis de regresión logística para identificar los factores asociados, presentados como odds ratios con intervalos de confianza del 95%.

ResultadosLa prevalencia de MGF entre las hijas fue del 24%. Los factores significativamente asociados con la MGF fueron la edad, la región, la residencia, la educación y el índice de riqueza. Las hijas más jóvenes tenían más probabilidades de ser circuncidadas (p=0,000; IC95%: 0,066-0,274). La residencia rural aumentaba la probabilidad de MGF (OR=1,436; IC95%: 1,257-1,64). La educación primaria aumentaba las probabilidades de MGF (OR=1,334; IC95%: 1,127-1,58). Las madres que creían que la MGF debía continuar tenían más probabilidades de tener hijas circuncidadas (OR=1,464; IC95%: 1,305-1,642).

ConclusionesLa prevalencia de la MGF entre las hijas en Somalia está influida por la edad, la región, la residencia rural y la educación. Los resultados ponen de relieve la necesidad de programas educativos y de intervención específicos, especialmente en las zonas rurales, para reducir eficazmente las prácticas de MGF.

Female genital mutilation (FGM), also known as female circumcision, is a practice that involves the partial or complete removal of external female genitalia, causing injury to the genital organs and carried out for non-medical reasons.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) defines FGM as all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons, often with socio-cultural motivations.2 Typically, FGM is performed before the age of 15 and constitutes a form of violence against women, as it often occurs without their consent and awareness of potential complications.3 This harmful procedure is widely condemned by international organizations and human rights activists and constitutes a grave violation of the rights of women and girls.

The WHO classifies FGM into four types, each involving the removal or alteration of different parts of the female genitalia4: Type I involves partial or complete excision of the clitoral hood and glans. Type II entails partial or complete removal of the clitoral hood and glans, as well as the labia minora, the inner folds of the vulva. Type III, infibulation, is the most severe form and involves narrowing of the vaginal opening by creating a seal through cutting and repositioning the labia minora or majora, sometimes involving stitching. It may also involve removal of the clitoral prepuce or clitoral hood and glans. Type IV encompasses all other harmful procedures on female genitalia for non-medical reasons, including pricking, piercing, incising, scraping, and cauterizing the genital area.

FGM is a human rights violation with no health benefits and can cause serious short- and long-term harm to the physical and psychological well-being of victims.4–7 A systematic review of 44 primary studies involving almost 3million participants revealed a strong association between FGM and various obstetric complications, including prolonged labor, obstetric lacerations, instrumental delivery, obstetric hemorrhage, and difficult delivery.8 Consequently, girls and women who have undergone FGM are at risk of experiencing complications throughout their lives.9 The reasons for performing FGM vary by location, but sociocultural factors play a significant role in driving the practice.3 Additionally, this practice is deeply rooted in ethnic, societal, and religious norms and customs.10

Over the past two decades, research has investigated the prevalence of FGM and its associated factors. Studies focusing on daughters aged 0–14 years in sub-Saharan Africa found a prevalence of 22.9%, with associated factors including the daughter's place of birth, mother's age, father's education, mother's perception of FGM, religious beliefs regarding FGM, mother's age at circumcision, residence in rural areas, and community literacy level.1,11 Similarly, studies among women aged 15–49, both married and unmarried, have shown that lower maternal education, family history of FGM, and belonging to the Muslim religion increase the likelihood of FGM. Conversely, higher paternal education for girls, living in urban areas, FGM literacy, and low community FGM prevalence were associated with a reduced likelihood of FGM.1,5,7,12–19

Globally, an estimated 200 million girls and women have experienced FGM, with the number expected to increase due to global population growth.3 This practice is prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa, the Arab States, parts of Asia, Eastern Europe, and Latin America, as well as in some countries in Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand.3 However, the most significant prevalence is observed in nations within the Sub-Saharan African region, attributed to strong sociocultural influences, scarce resources, and high levels of illiteracy, which facilitate the secretive practice and underreporting.20,6

In Somalia, FGM has been practiced for decades, and the country has one of the highest rates of FGM globally, following Guinea, Djibouti, and Egypt.12 Despite global criticism, FGM remains widely practiced in Somalia. According to the Somalia Demographic Health Survey 2020 (SDHS 2020), circumcision among women aged 15–49 is high, at 99%,21 indicating Somalia has the highest rate of FGM in the world. The SDHS 2020 also reveals that the pharaonic type of circumcision is the most common in Somalia, performed on 64% of women, while 12% have undergone the intermediate type and 22% the Sunni type. The majority of women (71%) aged 15–49 were circumcised between the ages of 5–9 years.

Despite these statistics, knowledge about the scope and causes of FGM in Somalia remains limited, with little research on associated factors at the national level. Furthermore, few studies have focused on FGM practices and attitudes, and to our knowledge, no previous research has utilized SDHS data. Therefore, understanding factors associated with FGM is critical for developing effective policies to prevent and address its effects, aligning with the international community's commitment to ending FGM as a harmful traditional practice by 2030.22

In addition, the main contribution of this study lies in its pioneer use of the first-ever SDHS Data to examine the prevalence and determinants of female genital mutilation. Through this unique approach, the research fills a significant knowledge gap and enhances the understanding of the complex dynamics surrounding FGM in Somalia. The findings provide valuable information for primary care practitioners by shedding light on the prevalence and associated factors that influence FGM practices. This knowledge can assist healthcare professionals in delivering patient-centered care and addressing the specific health needs of women affected by FGM. Furthermore, the study aligns with broader efforts to promote gender equality and women's empowerment, as outlined in the Sustainable Development Goals. By addressing the prevalence and determinants of FGM, the research contributes to the global goal of eliminating harmful practices and advancing gender equality, ultimately fostering a more inclusive and healthier society.

MethodsDataThe dataset on women was obtained from the 2020 Somalia Demographic and Health Survey (SDHS), the first nationally representative survey conducted by the Somalia National Bureau of Statistics from January 2018 to February 2019. Somalia, located in the Horn of Africa, covers an estimated 637,657km2 and features a terrain consisting primarily of plateaus, plains, and highlands. Its coastline, stretching over 3333km along the Gulf of Aden to the north and the Indian Ocean to the east and south, is the longest in Africa. Somalia borders Djibouti to the northwest, Ethiopia to the west, and Kenya to the southwest.

The survey aimed to provide key indicators for the entire country, as well as for each of the eighteen pre-war geographical regions and specific urban, rural, and nomadic areas. Due to security concerns, certain regions like Lower Shabelle, Middle Juba, and parts of Bay were excluded, resulting in a total of 47 sampling strata. A three-stage stratified cluster sample approach was employed in urban and rural areas, utilizing probability proportional to size for sampling Primary Sampling Units (PSUs) and Secondary Sampling Units (SSUs) at different stages to ensure survey precision consistency across regions.21

In the first stage, 35 Enumeration Areas (EAs) were sampled within each stratum based on digitized dwelling structures, totaling 1433 EAs across urban, rural, and nomadic areas. Household listings were conducted in selected urban and rural EAs, with births and deaths recorded. Subsequently, in the second stage, 10 EAs were sampled from the initial set of 35, and 30 households were selected from each of these 10 EAs. A total of 16,360 households from 538 EAs were covered in the third stage. The survey focused on interviewing ever-married women aged 12–49 and never-married women aged 15–49, alongside administering household and maternal mortality questionnaires.21

For this study, the women's file containing data of women aged 15–49 was analyzed. After excluding missing values, a sample of 10,573 women was used to assess the prevalence and associated factors of FGM. Sampling weights were applied to ensure accurate population representation and only complete cases on all variables of interest were included in the analysis.

Study variablesThe outcome variable in this study was FGM among daughters. The survey item “Respondent Circumcised” was assessed, a dichotomous (Yes/No) variable. Women indicating they had been circumcised were then asked if their genital area had been sewn closed, with responses coded as ‘Yes’ and ‘No’.

Independent variables were selected and included in the analysis based on the following criteria:

- •

Data availability: Variables were chosen based on the information available within the SDHS datasets.

- •

Relevance to FGM: Variables were chosen based on their potential to influence the outcome variable, considering published studies on FGM in Somalia and other African countries.

- •

Prior research: Variables were selected based on their established relevance to FGM in previous studies.

The independent variables included age, region, residence (urban, rural, nomadic), educational level, husband's educational level, marital status, exposure to media (radio and television), employment status of the respondents, husbands’ employment status, and wealth quintile.4–7

Data collectionData collection for the SDHS 2020 was conducted through a structured questionnaire administered using a Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) system, where interviewers used smartphones to record responses. The phones were equipped with Bluetooth technology to enable remote electronic transfer of completed questionnaires from interviewers to supervisors. Supervisors transferred completed files to the CSWeb server whenever Internet connectivity was available. Any revisions to the questionnaire were received by supervisors and interviewers by synchronizing their phones with the CSWeb server. The CAPI data collection system employed in the SDHS 2020 was developed by UNFPA using the mobile version of the Census and Survey Processing System (CSPro).21

Ethical considerationsEthical considerations were paramount throughout the SDHS 2020. The survey adhered to the following principles:

- •

Informed consent: Participants were fully informed about the study's purpose, procedures, and potential risks, and provided written consent before participating.

- •

Confidentiality: All data collected was anonymized, and only aggregated results were disseminated.

- •

Privacy: Interviews were conducted in a private setting, and participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses.

- •

Respect for participants: Interviewers were trained to treat participants with respect and sensitivity, particularly when collecting information about sensitive topics like GBV and FGM.

- •

Data security: Data was securely stored and protected according to international standards.

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 17.0 software. Initially, a univariate analysis was performed on selected variables, presenting the results in terms of frequency and percentage. Subsequently, a bivariate analysis, specifically a crosstabulation, was conducted to examine the relationship between the dependent variable (FGM) and individual covariates. The Chi-square test was then employed to assess proportional differences between them.

To identify the associated factors of FGM, a multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the significance of the risk factors. The adjusted odds ratio (AOR) was calculated for each covariate at a 95% confidence level. A determinant was considered statistically significant if the p-value was less than 0.05. The sample weight calculated for the SDHS 2020 was incorporated into the analysis to ensure accurate population representation.

ResultsDescriptive statisticsTable 1 shows the descriptive statistics for categorical variables in this study. The age of respondents was grouped in the SDHS data into seven groups between the ages of 15 and 49. The majority of respondents were between 25 and 39 years old, or approximately 70%. In terms of geographical dispersion, respondents were from 16 regions of Somalia. Respondents from the regions of Togdheer, Sool, Sanaag, and Banadir predominated with about 37%, where Banadir and Bay regions are the most and least presented regions in the data, respectively. In addition, respondents’ places of residence were also categorized as urban, nomadic, and rural areas. About 40% of the respondents lived in rural areas, while about 31% were nomadic people, and the rest lived in urban settings. On the other hand, respondents were asked their highest education level; about 85% of them replied with no education, while about 11% replied with primary as their highest education level, while the higher education option was the least opted for with about 0.6%. Respondents were also asked if they listen to radio and watch television; however, the vast majority of them replied with a negative answer.

Univariate analysis of categorical variables of FGM in SDHS 2020 data.

| Variable | Categories | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15–19 | 265 | 2.51 |

| 20–24 | 1486 | 14.05 | |

| 25–29 | 2941 | 27.82 | |

| 30–34 | 2490 | 23.55 | |

| 35–39 | 2152 | 20.35 | |

| 40–44 | 874 | 8.27 | |

| 45–49 | 365 | 3.45 | |

| Region | Awdal | 510 | 4.82 |

| Woqooyi Galbeed | 823 | 7.78 | |

| Togdheer | 910 | 8.61 | |

| Sool | 985 | 9.32 | |

| Sanaag | 951 | 8.99 | |

| Bari | 656 | 6.20 | |

| Nugaal | 603 | 5.70 | |

| Mudug | 595 | 5.63 | |

| Galgaduud | 529 | 5.00 | |

| Hiraan | 442 | 4.18 | |

| Middle Shabelle | 507 | 4.80 | |

| Banadir | 1060 | 10.03 | |

| Bay | 190 | 1.80 | |

| Bakool | 686 | 6.49 | |

| Gedo | 563 | 5.32 | |

| Lower Juba | 563 | 5.32 | |

| Type of place of residence | Rural | 4271 | 40.40 |

| Urban | 3002 | 28.39 | |

| Nomadic | 3300 | 31.21 | |

| Highest educational level of respondent | No education | 8997 | 85.09 |

| Primary | 1217 | 11.51 | |

| Secondary | 296 | 2.80 | |

| Higher | 63 | 0.60 | |

| Listen to radio | Yes | 650 | 6.15 |

| No | 9923 | 93.85 | |

| Watch TV | Yes | 848 | 8.02 |

| No | 9725 | 91.98 | |

| Wealth index | Lowest | 2666 | 25.22 |

| Second | 2260 | 21.38 | |

| Middle | 1964 | 18.58 | |

| Fourth | 1897 | 17.94 | |

| Highest | 1786 | 16.89 | |

| Husband/partner's ever attended school | Yes | 8696 | 82.25 |

| No | 1877 | 17.75 | |

| Husband/partner worked in last 12 months | Yes | 4934 | 46.67 |

| No | 5639 | 53.33 | |

| Respondent worked in last 12 months | Yes | 130 | 1.23 |

| No | 10,443 | 98.77 | |

| Circumcision should continue or be stopped | Continue | 7980 | 75.48 |

| Stop | 2593 | 24.52 | |

| Daughter circumcised | Yes | 2764 | 26.14 |

| No | 7809 | 73.86 | |

Furthermore, in terms of wealth index, respondents were classified based on their assets into five groups. About 25% of them were classified into the lowest class and 21% into the second lowest class, while the middle class, fourth class, and highest class were about 18.6%, 17.9%, and 16.9%, respectively. Respondents were also asked if they had worked in the last 12 months; the vast majority, about 99%, replied with no as an answer. In addition, respondents were asked about their husbands’ level of education and their occupation status in the last 12 months. The majority of their husbands attended school at a rate of 82%; however, the status of employment was not that high. 47% of them did not work in the last 12 months, and the other 47% worked.

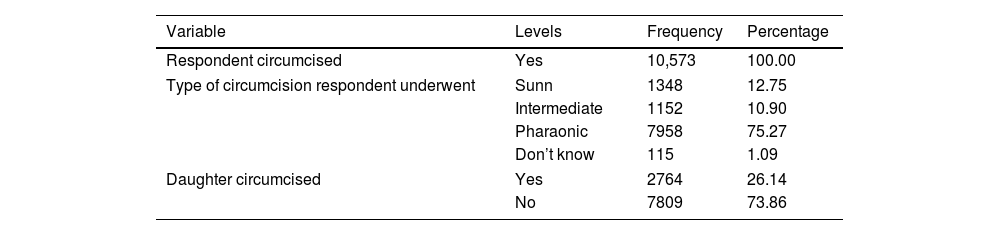

Prevalence of FGMIn Table 2, respondents were asked about their circumcision experience, the type undergone, whether their daughters also experienced circumcision, and their opinion on whether circumcision should continue or be stopped. Responses were that all of the respondents have been circumcised; the most common type of circumcision was Pharaonic, and the majority of them voted for continued circumcision. However, in terms of their daughters, 24% of them were only circumcised.

Analysis of associationIn Table 3, before doing logistic analysis, correlational analysis was performed to identify which predictor variables have a correlation with the outcome variable. Age variable showed a strong correlation with the outcome variable with a p-value of (0.000) indicating that age variable has a significant effect on the outcome variable. Region variable is also found to have a significant effect on the outcome variable. Again, type of place of residency of respondents showed to have a significant correlation with the outcome variable with a p-value of (0.000). Once again, educational status of the respondents resulted to have a significant correlation with the outcome variable. However, variables of watching television and listening to radio both showed no correlation with the dependent variable with a p-value greater than (0.005). In terms of wealth index, results show that this predictor has a significant correlation with the outcome variable.

Bivariate analysis of FGM in SDHS 2020 data.

| Factors | FGM | Chi-square | df | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | Frequency (percentage) | ||||

| Age in 5 year group | Yes | No | |||

| 15–19 | 8 (3.02) | 257 (96.98) | 988.86 | 6 | 0.000 |

| 20–24 | 56 (3.77) | 1430 (96.23) | |||

| 25–29 | 545 (18.53) | 2396 (81.47) | |||

| 30–34 | 772 (31.00) | 1718 (69.00) | |||

| 35–39 | 809 (37.59) | 1343 (62.41) | |||

| 40–44 | 391 (44.74) | 483 (55.26) | |||

| 45–49 | 183 (50.14) | 182 (49.86) | |||

| Region | |||||

| Awdal | 146 (28.63) | 364 (71.37) | 118.67 | 15 | 0.000 |

| Woqooyi Galbeed | 179 (21.75) | 644 (78.25) | |||

| Togdheer | 229 (25.16) | 681 (74.84) | |||

| Sool | 195 (19.80) | 790 (80.20) | |||

| Sanaag | 230 (24.19) | 721 (75.81) | |||

| Bari | 136 (20.73) | 520 (79.27) | |||

| Nugaal | 151 (25.04) | 452 (74.96) | |||

| Mudug | 151 (25.38) | 444 (74.62) | |||

| Galgaduud | 153 (28.92) | 376 (71.08) | |||

| Hiraan | 132 (29.86) | 310 (70.14) | |||

| Middle Shabelle | 139 (27.42) | 368 (72.58) | |||

| Banadir | 263 (24.81) | 797 (75.19) | |||

| Bay | 38 (20.00) | 152 (80.00) | |||

| Bakool | 247 (36.01) | 439 (63.99) | |||

| Gedo | 193 (34.28) | 370 (65.72) | |||

| Lower Juba | 182 (32.33) | 381 (67.67) | |||

| Type of residence | |||||

| Urban | 1230 (28.80) | 3041 (71.20) | 26.61 | 2 | 0.000 |

| Rural | 742 (24.72) | 2260 (75.28) | |||

| Nomadic | 792 (24.00) | 2508 (76.00) | |||

| Highest educational level | |||||

| No education | 2463 (27.38) | 6534 (72.62) | 49.27 | 3 | 0.000 |

| Primary | 232 (19.06) | 985 (80.94) | |||

| Secondary | 61 (20.61) | 235 (79.39) | |||

| Higher | 8 (12.70) | 55 (87.30) | |||

| Listen to radio | |||||

| Yes | 164 (25.23) | 486 (74.77) | 0.2979 | 1 | 0.585 |

| No | 2600 (26.20) | 7323 (73.80) | |||

| Watch TV | |||||

| Yes | 214 (25.24) | 634 (74.76) | 0.3921 | 1 | 0.531 |

| No | 2550 (26.22) | 7175 (73.78) | |||

| Wealth index combined | |||||

| Lowest | 586 (21.98) | 2080 (78.02) | 45.9512 | 4 | 0.000 |

| Second | 641 (28.36) | 1619 (71.64) | |||

| Middle | 591 (30.09) | 1373 (69.91) | |||

| Fourth | 487 (25.67) | 1410 (74.33) | |||

| Highest | 459 (25.70) | 1327 (74.30) | |||

| Husband/partner's ever attended school | |||||

| Yes | 2312 (26.59) | 6384 (73.41) | 5.0211 | 1 | 0.025 |

| No | 452 (24.08) | 1425 (75.92) | |||

| Husband/partner worked in last 12 months | |||||

| Yes | 1268 (25.70) | 3666 (74.30) | 0.9396 | 1 | 0.332 |

| No | 1496 (26.53) | 4143 (73.47) | |||

| Respondent worked in last 12 months | |||||

| Yes | 42 (32.31) | 88 (67.69) | 2.5914 | 1 | 0.107 |

| No | 2722 (26.07) | 7721 (73.93) | |||

| Circumcision should continue or be stopped | |||||

| Yes | 2217 (27.78) | 5763 (72.22) | 45.3204 | 1 | 0.000 |

| No | 547 (21.10) | 2046 (78.90) | |||

On the other hand, responses in regards respondent's educational status of their husbands’ results reveal that education status of husbands have significant correlation with the outcome variable. While husbands ‘employment status in the last 12 months shown no correlation with the outcome variable with a p-value of (0.332). In addition, respondents’ work status in the last 12 months showed no correlation with outcome variable. However, respondent's opinion in regards the circumcision weather it should be stopped or not, showed a significant correlation with the outcome variable. Thus, The Chi-square analysis showed that age, region, type of residency, respondents’ highest level of education, wealth index, husbands’ education status and respondents’ opinion in regards circumcision were statistically significantly associated with FGM among daughters in Somalia at 95% level of significance, therefore, these variables will be used as predictors in regression analysis.

Regression analysisResults of binary logistic regression analysis as presented in Table 4, show that that likelihood of circumcising daughters is least when mothers are in the age groups between 30 and 49 years old compared to age groups between 15 and 29 years. However, these results shown that age group of 15–19 has no significant effect on the outcome variable. In addition, region variable shown mixed results compared to the reference region where certain regions were found to be statistically significant and higher odds ratio. In terms of place of residency, rural settings were found to have higher likelihood of circumcising daughters with odds ratio of (OR=1.436, CI=1.257–1.64) compared to urban settings. In educational status of respondents, respondents who completed primary education had higher odds ratio (OR=1.334, CI=1.127–1.58) and was statistically significant compared to no education respondents.

Logistic regression of FGM in SDHS 2020 data.

| Variable | Levels | Odds ratio (OR) | Coefficient SE | 95% confidence interval (CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in 5-year group | 15–19 | Ref | |||

| 20–24 | 0.797 | 0.307 | 0.375–1.696 | 0.556 | |

| 25–29 | 0.135 | 0.049 | 0.066–0.274 | <0.001 | |

| 30–34 | 0.067 | 0.024 | 0.033–0.137 | <0.001 | |

| 35–39 | 0.048 | 0.017 | 0.023–0.098 | <0.001 | |

| 40–44 | 0.035 | 0.013 | 0.017–0.072 | <0.001 | |

| 45–49 | 0.028 | 0.011 | 0.013–0.058 | <0.001 | |

| Region | Awdal | Ref | |||

| Woqooyi Galbeed | 1.445 | 0.198 | 1.105–1.889 | 0.007 | |

| Togdheer | 1.301 | 0.173 | 1.002–1.689 | 0.048 | |

| Sool | 1.739 | 0.235 | 1.334–2.267 | <0.001 | |

| Sanaag | 1.138 | 0.15 | 0.879–1.472 | 0.327 | |

| Bari | 1.466 | 0.214 | 1.102–1.95 | 0.009 | |

| Nugaal | 1.161 | 0.169 | 0.873–1.543 | 0.306 | |

| Mudug | 1.087 | 0.157 | 0.818–1.444 | 0.564 | |

| Galgaduud | 0.901 | 0.133 | 0.675–1.202 | 0.478 | |

| Hiraan | 0.903 | 0.139 | 0.668–1.22 | 0.507 | |

| Middle Shabelle | 1.036 | 0.154 | 0.773–1.387 | 0.815 | |

| Banadir | 1.094 | 0.142 | 0.848–1.412 | 0.489 | |

| Bay | 1.791 | 0.393 | 1.165–2.752 | 0.008 | |

| Bakool | 0.687 | 0.093 | 0.526–0.897 | 0.006 | |

| Gedo | 0.649 | 0.093 | 0.491–0.859 | 0.003 | |

| Lower Juba | 0.741 | 0.106 | 0.56–0.981 | 0.036 | |

| Type of place of residency | Urban | Ref | |||

| Rural | 1.436 | 0.097 | 1.257–1.64 | <0.001 | |

| Nomadic | 1.391 | 0.122 | 1.172–1.651 | <0.001 | |

| Participant's highest education level | No Education | Ref | |||

| Primary | 1.334 | 0.115 | 1.127–1.58 | 0.001 | |

| Secondary | 1.151 | 0.191 | 0.832–1.593 | 0.394 | |

| Higher | 1.74 | 0.702 | 0.789–3.837 | 0.169 | |

| Wealth index | Lowest | Ref | |||

| Second | 0.792 | 0.059 | 0.684–0.916 | 0.002 | |

| Middle | 0.703 | 0.066 | 0.585–0.843 | <0.001 | |

| Fourth | 0.845 | 0.083 | 0.697–1.025 | 0.087 | |

| Highest | 0.793 | 0.083 | 0.647–0.973 | 0.026 | |

| Husband/partner's ever attended school | Yes | Ref | |||

| No | 1.057 | 0.076 | 0.918–1.216 | 0.442 | |

| Circumcision should continue or be stopped | Yes | Ref | |||

| No | 1.464 | 0.086 | 1.305–1.642 | <0.001 | |

In addition, the other fourth levels of wealth index showed less likelihood of circumcising daughters compared to the lowest level. However, the fourth level shown no statistically significant with a p-value greater then (0.05). In terms of educational status of husbands, those who attained school had a bit likelihood of circumcising daughters (OR=1.057, CI=0.918–1.216), however, it was not statistically significant. While, respondents’ opinion in regards continuum of circumcision showed statistically significance, however, respondents replied with no were more likelihood to circumcise their daughters (OR=1.4641, CI=1.305–1.642) compared to respondents replayed yes as responses.

DiscussionThis study aimed to determine the prevalence and determinants of FGM among daughters of women of reproductive age in Somalia, utilizing data from the first nationally representative Somalia Demographic and Health Survey (SDHS 2020).21 This pioneering approach, utilizing SDHS data for the first time to assess FGM, reveals a prevalence of 24% among daughters, a figure lower than previous reports from Ethiopia, including the Habab Guduru district (48%), national reports (38%), and the Oromia region (34.9%).23

Our findings underscore the possibility of intergenerational change in FGM practices. Although FGM remains prevalent in Somalia, this study highlights a significant reduction in the practice among daughters compared to their mothers, a trend not widely documented before. This observation suggests that educational and cultural interventions may be influencing attitudes and practices, creating a window of opportunity for more effective prevention strategies.

The study identified several key reasons for circumcising daughters: avoiding shame, upholding traditional and religious respect, maintaining virginity, ensuring vulvar hygiene, and reducing sexual desire. These align with findings from a study conducted in the Hadiya zone, Southern Ethiopia.24 The prevalence of FGM in our study was significantly associated with age, with younger daughters having approximately twice the odds of undergoing FGM compared to older daughters (p-value: 0.000, 95% CI: 0.066–0.274).25 This trend aligns with other studies conducted in Ethiopia, indicating the potential for a shift in attitudes as daughters gain greater agency over their bodies.25

Our analysis further revealed that knowledge of the adverse health effects of FGM was significantly associated with the circumcision status of daughters. Mothers who completed primary education had higher odds (OR=1.334, CI=1.127–1.58) of not circumcising their daughters compared to those with no formal education.1 This finding is comparable to a study in Western Ethiopia where mothers with good knowledge about FGM had 86% lower odds of having circumcised daughters compared to those with poor knowledge,1 as well as findings from the Amhara region.26 This reinforces the critical role of education in shaping attitudes and behaviors related to FGM.

Living in rural settings was associated with a higher likelihood of circumcising daughters (OR=1.436, CI=1.257–1.64) compared to urban areas, consistent with previous studies in Ethiopia.24 This finding emphasizes the need for tailored interventions that address the specific contextual factors influencing FGM in rural communities.

Finally, the circumcision status of daughters was associated with the belief in the continuation of the practice in multivariate analysis (AOR=1.464; 95% CI: 1.305–1.642).24 This finding aligns with a study conducted in Southern Ethiopia, which found that the belief in the continuation of the practice was significantly associated with circumcision status in multivariate analysis (AOR=8.22; 95% CI: 1.10, 61.8).24 This suggests that challenging deeply ingrained beliefs about the necessity of FGM is crucial for long-term change.

Novelty of findings and implicationsThis study makes a novel contribution by utilizing the first nationally representative SDHS 2020 data to assess FGM practices and associated factors among daughters. Previous research in Somalia primarily focused on FGM prevalence among adult women, leaving a significant gap in understanding how the practice is evolving across generations. Our findings demonstrate that while FGM remains prevalent, there is a notable reduction in the practice among daughters compared to their mothers. This underscores the potential for intergenerational change and provides valuable insight for designing more effective prevention strategies in Somalia and similar regions.

The study also emphasizes the importance of considering modifiable contextual factors, such as rural residence, education, and beliefs, in developing targeted interventions. This robust analysis provides a solid foundation for public health policies and intervention programs that effectively address the complex social and cultural determinants of FGM.

LimitationsIt is important to acknowledge some limitations of the study. The SDHS 2020 data, while representing a significant advance in data collection for Somalia, does not capture all regions due to security concerns. This may limit the generalizability of our findings to the entire country. Notably, the SDHS 2020 data does not include information on whether daughters who are not currently circumcised are at risk of future circumcision. Additionally, the study relies on self-reported data, which may be subject to social desirability bias.

Future directionsThis research highlights the need for continued monitoring and evaluation of FGM trends in Somalia, particularly among younger generations. Further research is needed to explore the specific factors contributing to the observed intergenerational shift in practices. Longitudinal studies that track changes in attitudes and behaviors over time would provide valuable insights into the effectiveness of intervention programs. Collaborative efforts involving community leaders, healthcare professionals, educators, and policymakers are essential for developing and implementing effective FGM prevention strategies that address both the social and cultural determinants of this harmful practice.

To effectively address FGM and promote women's empowerment in Somalia, a multi-pronged approach is essential. Our findings suggest the following specific actions:

- •

Education and awareness: Increase access to quality education for girls and women in Somalia, with particular focus on rural communities. Educational programs should include comprehensive information on the health risks of FGM and promote alternative practices.

- •

Community-based interventions: Engage with community leaders, religious figures, and traditional healers to challenge harmful beliefs and practices associated with FGM. Develop culturally sensitive interventions that promote positive attitudes toward women's health and rights.

- •

Healthcare provider training: Train healthcare professionals on the identification, management, and prevention of FGM. Equip them with the skills to provide compassionate care to women affected by FGM and to offer counseling and support.

- •

Empowerment programs: Support programs that promote women's economic and social empowerment. This includes providing access to vocational training, micro-credit schemes, and opportunities for leadership development.

Collaborative efforts involving community leaders, healthcare professionals, educators, and policymakers are essential for developing and implementing effective FGM prevention strategies that address both the social and cultural determinants of this harmful practice.

ConclusionFGM prevalence among daughters in Somalia is 24%, lower than in Ethiopia, driven by cultural and religious reasons. Significant factors influencing FGM include age, region, rural residency, and education levels. Younger daughters and those in rural areas are more likely to be circumcised. Most procedures are performed by traditional circumcisers. Educational status of mothers and wealth index also play crucial roles. Targeted educational and intervention programs, especially in rural areas, are essential to reduce FGM practices.

In summary, the study provides valuable insights into the current state of FGM practices among daughters in Somalia. While FGM remains a concern, our findings highlight a potential shift in attitudes and practices across generations. The study emphasizes the importance of addressing modifiable factors such as education, rural residence, and deeply held beliefs about FGM. Further research is needed to understand the specific drivers of this intergenerational change and to develop effective interventions that promote the abandonment of FGM and the empowerment of women in Somalia.

- •

First national study on FGM among daughters in Somalia: This study pioneers the use of the Somalia Demographic and Health Survey (SDHS 2020) to assess FGM prevalence and associated factors among daughters of reproductive-age women.

- •

Evidence of potential intergenerational change: The study reveals a lower prevalence of FGM among daughters compared to their mothers, suggesting a possible shift in practices and attitudes.

- •

Key modifiable factors identified: The study pinpoints rural residence, lack of education, and beliefs in the continuation of FGM as significant contributors to the practice.

- •

Implications for intervention strategies: These findings provide a foundation for developing targeted interventions focused on education, community engagement, and challenging harmful beliefs, contributing to the elimination of FGM in Somalia.

- •

Alignment with SDG Goal 5, Target 5.3: This study is aligned with SDG Goal 5, Target 5.3, which aims to eliminate all harmful practices, such as child, early and forced marriage and female genital mutilation. By focusing on FGM prevalence and associated factors among daughters, this research contributes to a deeper understanding of the drivers of this harmful practice and potential strategies for its elimination in Somalia.

The authors affirm that there are no conflicts of interest pertaining to the publication of this article.