Introduction

Family physicians see patients every day with a wide spectrum of health problems, and thus serve as the gateway to the health care system. It is often difficult to reach a diagnosis, and health professionals often face different degrees of uncertainty. As noted by Stephens,1 the patient forms part of various social systems, and to really know the patient, his or her personal, familial and social circumstances need to be known as completely as possible.

Psychosocial problems (PSP) are among the reasons for consulting, and are becoming increasingly important because of their frequency and implications for diagnosis and treatment. De la Revilla2 defined PSP as "those situations of social stress that produce or facilitate the appearance, in affected individuals, of somatic, psychiatric or psychosomatic illness, giving rise to family crises and dysfunction with alterations in familial homeostasis capable of generating clinical manifestations in some of its members." If the defining feature of PSP is not their clinical expression but their cause--social stress--the problems family physicians have in detecting these patients during primary care consultations are understandable. Identifying these patients involves bringing to the foreground those motives that underlie the patient´s needs--in other words, the situations that alter family and social dynamics. Higgins3 claimed that approximately half of all PSP remained undiscovered in primary care consultations. In daily practice, patients do not seek care directly for their PSP,4 and this makes it difficult for physicians to find signs suggestive of PSP in the problems patients apparently seek help for. Improvements in diagnosis and treatment of PSP by general practitioners enhance the quality of care5 and are more cost-effective than care based on specialized services.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the 28-item Goldberg General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) as a detector of PSP, and the relationship between questionnaire scores and causal factors of PSP (stressful life events), one of their consequences (use of services) and some individual variables (age, sex, employment status, socioeconomic group and educational level).

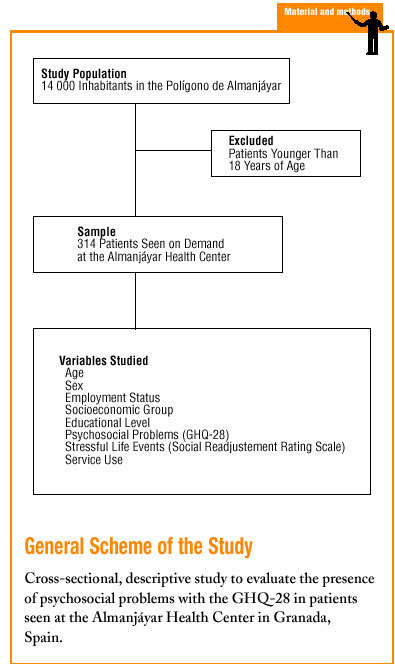

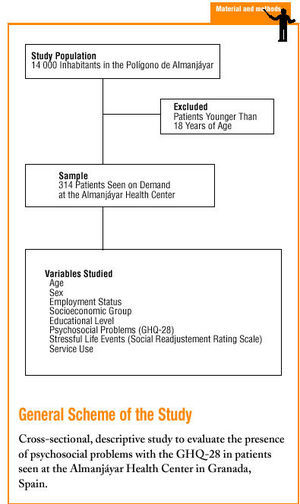

Material and methods

Three physician's offices at the Almanjáyar Health Center in Granada (Southern Spain) were selected for the present study. Most patients seen at this health center are of middle-lower socioeconomic status. Systematic sampling based on the list of patients with scheduled appointments was used to obtain data for 314 patients who agreed to participate in the study. The percent level of participation was 85%. At the end of the scheduled consultation, each patient was invited to be interviewed in a different office during approximately 10 to 15 minutes so that they could respond to items on the GHQ-286 and the Social Readjustment Rating Scale of Holmes and Rahe.7 The demographic variables recorded were age, sex, employment status, socioeconomic group8 and educational level.9 Persons younger than 18 years were excluded.

Goldberg GHQ-28

During the interview patients responded to the GHQ-28, which was divided into four subscales of 7 items each. These sections dealt with somatic symptoms, anguish/anxiety, social dysfunction and depression. Suspected PSP was recorded when the number of responses in the two right-hand columns was 8 or higher.

Social Readjustment Rating Scale

To evaluate stressful live events (SLE) we used the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS) of Holmes and Rahe.7 Readjustment was defined by these authors as "the amount and duration of change in the subject's accustomed pattern of life." Only those SLE during the previous year were recorded. The SRRS consists of 43 items ranked from greatest to least stressfulness; each event is scored in life-change units (LCU) from 100 (most serious) to 11 (least serious). A total score of 150 LCU or higher is considered to indicate a level of stress that may affect individual or family health.

Employment Status

This was recorded as actively employed, unemployed, student or retired.

Socioeconomic Group Indicator

The National Occupational Classification was used to assign the individual's professional qualifications to one of 6 socioeconomic groups: I: executive and high-level technical directors; II: managerial and technical; III: mid-level management; IV: skilled and semiskilled workers in industry; commerce and services, self-employed; V: unskilled workers; or VI: other unspecified.

Educational Level Indicator

This indicator was used to classify patients in seven levels according to the highest level of education completed: 1: illiterate; 2: no formal education, able to read and write; 3: primary school; 4: secondary school; 5: secondary school, university track; 6: three-year (or less) university certification; or 7: university.

Use of Services

The number of visits to the health center requested by the patient during the previous year was determined from the medical record. Individuals were classified as normal user or overusers depending on the frequency of visits to the health center. On the basis of an earlier study of health service usage patterns at the Cartuja Health Center (in the same city as the health center studied here),10 we identified patients who had 8 consultations or fewer during the preceding year as normal users, and patients who came to the health center more than 8 times during that period as overusers.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive analysis was used for each variable to report the frequency distribution and summary measures such as the mean, median and standard deviation. The variable "total GHQ score" was categorized as <8 or >=8 to study the associations between this and other variables. The chi-squared test was used for all contingency tables, and when appropriate Fisher´s exact test was used with 2x2 tables, and a generalization of Fisher´s exact test was used for RxC comparisons. To identify which factors were independently associated with high GHQ scores, we used logistic regression with a model that considered all variables. Checking the goodness of fit of the model with the Hosmer-Lemeshow test showed that the results were not significant. The findings with the goodness of fit model are expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

GHQ Scores

Mean score on the GHQ was 9.25 (SD, 6.71). Slightly more than half (56%) of the patients interviewed scored 8 or higher, and were therefore considered to have a possible PSP.

Stressful Life Events

Of the 314 patients interviewed, 147 (47%) reported a number of SLE during the year preceding the interview that yielded a score of 150 LCU or more on the SRRS.

Use of Services

We detected 151 (48%) individuals who were classified as overusers (more than 8 consultations during the previous year).

Age and Sex

Distribution of the participants according to age group was as follows: 29 years or younger: 63 patients (20%); 30 to 59 years: 202 (64.3%); older than 60 years: 49 patients (15.6%). The youngest participant was 20 years old, and the oldest was 78. Mean age was 42.3 years (SD, 13.85 years). Less than one third (30.6%) were men, and 69.4% were women.

Employment

Employed persons made up 44.3% of the participants, unemployed persons made up 36.7%, and the remaining 18.8% of the patients were retired.

Socioeconomic Group and Educational Level

Three fourths (75%) of the participants were considered to belong to group IV (skilled or semiskilled workers in industry or services, or self-employed persons). At the lowest end of the scale, unskilled workers (group V) made up 15% of the sample. About half of the participants (155, 49.4%) had completed primary school, 104 (33.1%) had received no formal schooling but were able to read and write, and 22 persons (7%) stated that they were illiterate.

Univariate Analysis

Relationship between level of stress (stressful life events) and GHQ-28 score. High GHQ scores were associated with higher numbers of SLE during the previous year. Almost three fourths (72%) of the patients who had a cumulative score of 150 or more LCU had a high GHQ score, whereas only 43% of the patients with a cumulative score of 149 LCU or less also had a high GHQ score (Table 1). When the results were stratified into 5 groups according to GH Q score, differences between groups emerged (Table 2). Individuals with a high GHQ score more often had very high SLE results (items 1 to 7, for a total of 100 to 50 LCU). In contrast, in the group with the lowest SLE results (items 32 to 43, for a total of 20 to 11 LCU) a GHQ score greater than 8 was less frequent.

Relationship between use of services and GHQ score. As shown in Table 3, overusers had higher GHQ scores than normal users (P<.001).

Relationship between demographic variables and GHQ scores. Age and sex: the percentage of individuals between 30 and 59 years of age with a high GHQ score was slightly higher than in other age groups, although the difference was not statistically significant. Female sex was associated with higher GHQ scores (Table 4).

Employment status. We found no statistically significant differences between different groups based on employment status (Table 5).

Socioeconomic group and educational level. There appeared to be a relationship between low socioeconomic group (groups IV and especially V) and high GHQ scores (Table 5). We noted that as level of education increased, the risk of a high GHQ score decreased (Table 5). A higher level of education was thus considered a protective variable.

Multivariate Analysis

Two risk categories for the variables related with the appearance of high GHQ-28 scores (Table 6) were suggestive of the presence of PSP: high cumulative SLE results (>=150 LCU), associated with a 2.65-fold higher risk (CI, 1.50-4.68), and female sex (OR, 2.15; CI: 1.14-4.04). Less significant associations were also found for lowest socioeconomic group (level V), with an OR of 2.17 (CI, 0.57-8.36), age group 30 to 59 years (OR, 1.92; CI, 0.93-3.98), and health care service overuser status (OR, 1.71; CI, 0.79-3.69).

Discussion

The difficulties in rapidly detecting requests for health care that may have their origin in a PSP make it necessary to search for systems that enable us to discover which patients are subjected to social stress. According to Hoeper et al,11 using a simple questionnaire that explores somatic, psychological and behavioral processes is potentially useful for discovering psychosocial distress. Goldberg's GHQ-28, validated for the Spanish population by Lobo et al,13 has been shown to be a good instrument for detecting problems of social dysfunction, psychosomatic problems, anxiety and depression.12 Our choice of this test as an instrument to detect PSP was based on three reasons. Firstly, the GHQ is shorter than similar instruments and yet is similar to them in validity and discriminatory power, and is therefore considered more appropriate for use in primary care settings.14 Secondly, for a cut-off score of 7/8, the sensitivity (77%) and specificity (90%) of the GHQ-28 are acceptable for instruments of this type and similar to those reported in other countries that have tested questionnaires that take longer to administer and interpret. Thirdly, the GHQ comprises, in addition to the overall evaluation, four subscales that provide additional information on psychosomatic symptoms, anguish/anxiety, social dysfunction, and depression.

The relationship between SLE and GHQ scores is of considerable importance. In our study we found that persons with an SLE score of 150 LCU or higher also had high GHQ scores. Likewise, persons with a suspected PSP (high GHQ score) reported more serious SLE (items 1 to 7 in the SRRS). This relationship between SLE and PSP has been observed by other researchers. Chen et al20 found that 66% of their patients who had experienced an SLE had PSP. In addition, Aro et al21 reported, in a study of SLE in adolescents, that there was a clear relationship between these events and PSP. De la Revilla et al22 documented that 65% of the patients with a large number of SLE also had PSP.

In a study of service usage, García Lavandera et al23 found an association between overuse and psychiatric distress measured with the GHQ. We also noted this association: 76% of the overusers in our series of patients had high GHQ scores. This may reflect, as suggested by Berwick et al,24 that individuals with PSP need more frequent care from the health system, and that this in turn leads to increased use. However, we believe another plausible explanation (as noted by Garfield et al25) may be that patients with PSP generally have more illnesses and consequently seek care more often.

The fact that PSP can lead to an increase in health care service use has been noted by others. De la Revilla and de los Ríos26 found that 77% of the patients who were overusers had a PSP, and Tessler et al27 and Liptzin et al28 found that subjects diagnosed as having a PSP had higher rates of consultation then the rest of the patients.

Turning to the relationship between individual variables and the GHQ, we found that persons between the ages of 30 and 59 years, and to a lesser degree persons older than 60 years, had higher GHQ scores. During certain periods of life, persons may be exposed to more social or familial stress, or their sensitivity to these factors may vary. This would be consistent with the tendency, described by Verhaak and Wennik,29 to perceive somatic processes when patients are younger, and PSP in middle-aged patients.

Our analysis of the relationship between PSP and sex showed that women generally had higher GHQ scores than men. This was also noted in a study by Vázquez-Barquero et al,30 and may be a reflection, as Kessler et al31 suggested, of the tendency for women to be less reticent than men in asking for help with psychological problems.

With regard to the relationship between employment status and PSP, Deniel et al32 claimed that unemployment and occupational disability were the two events with the greatest impact on the genesis of these problems. In the present study we found no significant differences in PSP between persons of different employment status.

Our analysis of socioeconomic group showed that patients in the most disadvantaged groups (IV and V) clearly tended to have higher GHQ scores. We may therefore consider persons in these socioeconomic strata as a risk group for PSP. As noted by Sinn and Berman,33 worse living conditions make persons in lower social classes more likely to become ill and to have SLE.

When we examined the influence of educational level on the appearance of PSP, we found that the risk of a high GHQ score decreased as level of education increased. This may be a result of the fact that the relationship between health status and social class is not static, but is mediated by cultural factors. In other words, within every society there are cultural elements that can alter the effect of social class on the process of becoming ill.

To conclude, we note that the GHQ-28 is a good instrument for detecting PSP, and the GHQ score is related in a statistically significant manner with the presence of recent SLE and with female sex. Although certain trends were noted for the other variables studied here, none of them attained statistical significance.