Patients with diabetes are prone to cognitive decline, including memory loss, decreased attention, and processing speed. This study aims to evaluate cognitive impairment in patients with diabetes and the factors associated with cognitive decline.

Materials and methodsA cross-sectional study was conducted over 5 months targeting 318 previously diagnosed patients with diabetes from 2 endocrinology clinics. The Arab version of the Mini-Mental State Examination assessed cognitive function through 11 items exploring 6 cognitive domains. Participants' general characteristics, lifestyle, and medical history were collected. They were also asked about the management of their diabetes (type of and adherence to medication and doing regular laboratory tests or glycemic monitoring at home). Other information, such as glycated hemoglobin A1c, cholesterol, and triglycerides level, was retrieved from the patient's files while noting the patient's systolic and diastolic blood pressures.

ResultsPatients had a mean age of 59.8 (10.7). Around 68% of patients had a possible cognitive impairment, and 31.8% a normal cognitive function. Significantly lower scores were noted among females (20.0; P < .001), and older patients had lower cognitive functions than others (19.4; P < .001). Illiterate had significantly lower scores (15.0) than those with advanced education (24.9; P < .001). Participants with diabetes for more than 5 years (20.8) and those with uncontrolled glycemia (20.8) had lower cognitive function than patients diagnosed more recently (22.2; P = .021) or those with controlled glycemia (23.1; P < .001). A cognitive decline was found among those with total cholesterol ≥200 mg/dL (20.7 vs. 21.9; P = .044), a systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg or more (20.0 vs. 22.5; P < .001), and hematocrit levels below 40% (20.6 vs. 22.4; P = .002). After adjusting for covariates, a lower cognitive function score was found per increase of 1 year of age (b=−0.120, CI (−0.13, −0.03); P = .038) and among females (−0.186 (−3.30, −0.35); P = .016). An increase of a factor of 0.342 was found between the levels of education (CI (0.71–2.04); P < .001), and patients with uncontrolled glycemia had a significantly lower score than others. Moreover, having a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg decreased the cognitive function score by a factor of 0.147 (CI (−2.98, −0.01); P = .049).

ConclusionThe combined effect of these factors should be considered for treatment management and glycemic control to help early referrals of patients at risk.

Los pacientes con diabetes son propensos al deterioro cognitivo, incluida la pérdida de memoria, disminución de la atención y la velocidad de procesamiento. Este estudio tiene como objetivo evaluar el deterioro cognitivo en pacientes con diabetes y los factores asociados al deterioro cognitivo.

Materiales y métodosse realizó un estudio transversal durante cinco meses con 318 pacientes previamente diagnosticados con diabetes en dos clínicas de endocrinología. La versión árabe del Mini-Examen del Estado Mental evaluó la función cognitiva a través de 11 ítems que exploraban seis dominios cognitivos. Se recogieron las características generales, el estilo de vida y el historial médico de los participantes. También se les preguntó sobre el manejo de su diabetes (tipo y cumplimiento de la medicación y realización periódica de pruebas de laboratorio o seguimiento de la glucemia en casa). Otra información, como la hemoglobina glucosilada A1c, el nivel de colesterol y triglicéridos, se recuperó de los expedientes del paciente mientras se anotaban las presiones arteriales sistólica y diastólica del paciente.

ResultadosLos pacientes tenían una edad media de 59,8 ± 10,7 años. Alrededor del 68% de los pacientes presentaban un posible deterioro cognitivo y el 31,8% una función cognitiva normal. Se observaron puntuaciones significativamente más bajas entre las mujeres (20,0; p < 0,001), y los pacientes de mayor edad tenían funciones cognitivas más bajas que otros (19,4; p < 0,001). Los analfabetos obtuvieron puntuaciones significativamente más bajas (15,0) que aquellos con educación avanzada (24,9; p < 0,001). Los participantes con diabetes desde hacía más de cinco años (20,8) y aquellos con glucemia no controlada (20,8) tenían una función cognitiva más baja que los pacientes diagnosticados más recientemente (22,2; p = 0,021) o aquellos con glucemia controlada (23,1; p < 0,001). Se encontró un deterioro cognitivo entre aquellos con colesterol total ≥200 mg/dL (20,7 vs. 21,9; p = 0,044), presión arterial sistólica de 140 mmHg o más (20,0 vs. 22,5; p < 0,001) y niveles de hematocrito inferiores a 40. % (20,6 vs 22,4; p = 0,002). Después de ajustar por covariables, se encontró una puntuación de función cognitiva más baja por aumento de un año de edad (b = −0,120, IC (−0,13, −0,03); p = 0,038) y entre las mujeres (−0,186 (−3,30, −0,35);p = 0,016). Se encontró un aumento de un factor de 0,342 entre los niveles de escolaridad (IC (0,71-2,04); p < 0,001), y los pacientes con glucemia no controlada tuvieron una puntuación significativamente menor que el resto. Además, tener una presión arterial sistólica ≥140 mmHg disminuyó la puntuación de la función cognitiva en un factor de 0,147 (IC (−2,98, −0,01); p = 0,049).

ConclusiónEl efecto combinado de estos factores debe considerarse para el manejo del tratamiento y el control glucémico para ayudar a la derivación temprana de pacientes en riesgo.

Diabetes is a widespread chronic disease affecting millions of people worldwide. According to the International Diabetes Federation, approximately 537 million adults (aged 20–79) have diabetes.1 This prevalence is generally higher in low- and middle-income countries than in high-income countries.2 This is likely due to a combination of factors, including differences in lifestyle and diet, aging populations, and limited access to healthcare. Other factors include ethnicity, obesity, physical inactivity, family history, and gestational diabetes.2 Diabetes is often associated with multimorbidity since it can increase the risk of developing other chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes-related complications, including nerve damage and eye problems.3 Multimorbidity can complicate the management of diabetes, as it may require more intensive treatment and monitoring due to polypharmacy and significant lifestyle changes.4

Studies have shown a link between diabetes and cognitive impairment, particularly in older adults.5 People with diabetes may be at higher risk of developing cognitive impairment, including dementia and Alzheimer's.6 One possible reason for this link is that high blood sugar levels can damage blood vessels in the brain, leading to reduced blood flow and oxygen delivery, which can cause brain damage and cognitive impairment over time.7 Diabetes is also associated with inflammation, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance, possibly contributing to cognitive decline. In addition, some medications used to treat diabetes, such as insulin and sulfonylureas, have increased the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia.8 The odds of dementia development among patients with diabetes were 1.25–1.91 higher than others.9 Other modifiable risk factors can contribute to cognitive impairment, including lower education level, hearing loss, traumatic brain injury, high blood pressure, excessive alcohol consumption, obesity, smoking, depression, social isolation, not getting the recommended amount of physical activity, and air pollution.10 A recent report by the American Heart Association emphasized that some modifiable (weight, physical activity, blood pressure, cholesterol level, smoking, diet, alcohol, sleep, stress, and well-being) and non-modifiable risk factors (family history, race or ethnic background, age and gestational diabetes) can be controlled to prevent further dementia events.5,9

Diabetes is a significant health issue in Lebanon, as it is in many countries worldwide. The prevalence of diabetes among adults in Lebanon is around 8%11 and is expected to increase by 2045.12 This prevalence is higher in urban than rural areas, and disparities exist between different socioeconomic groups.13 Moderate awareness of their disease was found among patients with diabetes.14 Efforts to address diabetes in Lebanon include initiatives by the Ministry of Public Health to promote healthy lifestyles and increase access to diabetes care. Nevertheless, few studies were done in Lebanon to assess the association between diabetes and cognitive impairment, namely dementia. This study aims to evaluate cognitive impairment in patients with diabetes and the factors associated with cognitive decline.

Material and methodsStudy designAn observational cross-sectional study was conducted over 5 months (June–October 2022), targeting previously diagnosed patients with diabetes from 2 endocrinology clinics in the South of Lebanon. The study protocol, survey, and consent form were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the faculty of pharmacy at the Lebanese University.

Study sample and sample sizePatients were recruited from 2 external endocrinology clinics located next to 2 hospitals in the South of Lebanon. No criteria were based on sex, nationality, age, and ethnicity. Only those previously diagnosed with a medical file at the endocrinologists were invited to participate based on their clinic availability for routine follow-up. The sample size was determined using the Epi Info 7 software. A recent national survey in Lebanon reported that the prevalence of diabetes among adults is 7.95%.11 Therefore, the total number of potential participants was calculated considering this prevalence. As no similar studies related to cognitive function in Lebanon, the calculation assumed that the probability of having good mental and physical health was 50%. Considering a 95% confidence interval and a 5% acceptable margin of error, at least 384 participants were required. The sample included 318 patients. G power software calculated the corresponding power (70.7%).

Data collectionTwo pharmacists approached the patients during their internship time (Monday–Friday from 9 am to 4 pm), each in an external private endocrinology clinic. They explained the study's aims orally and invited them to participate by completing an online survey. The first page of the survey included the study's aims (written), the estimated time to answer the questionnaire (12–15 min), statements on the anonymity and confidentiality of their responses, and consent to use their data for research purposes only. Participation in the survey was strictly voluntary. Data related to the medical history and laboratory tests were retrieved from the patients' medical files after the approval of the endocrinologist and the patient.

Study toolAfter an extensive literature review, a uniform questionnaire was used for data collection. It was administered in Arabic (the official language in Lebanon). The first part included questions about the general characteristics of the participants (sex, age (categorized into <45, 45–65 or >60), height and weight (used to generate the Body Mass Index (BMI)), marital status (single/divorced or married), level of education, work status, perceived economic situation, and if they had medical insurance. This part also included information regarding their lifestyle, such as smoking status (current, former, or non-smoker), alcohol consumption, physical activity, following a special diet, and if they were current car drivers. The second part asked participants about their medical history, including other comorbidities (hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular diseases, chronic kidney disease, psychological disorders, and dysthyroidism). They were also asked about the management of their diabetes: the duration of the disease (<2, 2–5 or >5 years), if they had a controlled glycemia, type of medication used (tablets, injections, or both), adherence to medications, and doing regular laboratory tests or glycemic monitoring at home. The last part comprised the assessment of the cognitive function of the patients. The Arab version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) test was used.15 It included 11 items exploring 6 cognitive domains (orientation, recording of information, attention and calculation mind, word recall, language, and constructive praxis). Patients with a total score of less than 24 were considered at high risk of cognitive impairment. Other information related to laboratory tests, such as glycated hemoglobin A1c (HBA1c), total cholesterol, low-density lipoproteins (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), triglycerides, uric acid, hematocrit, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and vitamin B12 was retrieved from the patient's files. During the visit, the systolic and diastolic blood pressures were noted based on an examination performed by the endocrinologist. Values were then dichotomized based on the normal values adopted in the hospital.

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) Version 29. Categorical variables are presented through frequencies and percentages. These variables included the general characteristics of the patients and the questions related to their medical history and laboratory test results. The age, Body Mass Index (BMI), the mean of the laboratory results, and the cognitive function score are presented through means and standard deviations. Individual MMSE items were recorded, summed, and transformed as recommended.16 One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess the relationship between the cognitive function score and the general characteristics, medical history, and laboratory test variables. A multivariate analysis was performed using linear regression models to evaluate the combined effect of predictors on the cognitive function score. The confusion variables (or covariates) were considered if they had a statistically significant P-value (<.05) in the ANOVA analysis.

Ethical considerationsThe institutional review board of the Lebanese University faculty of pharmacy reviewed and approved the study protocol, tool, and consent form. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient. They were acknowledged that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw it at any point of the study with only provided answers registered. This study received no funding and no financial incentives were provided. Results were considered for research purposes only, with no potential conflict of interest to declare.

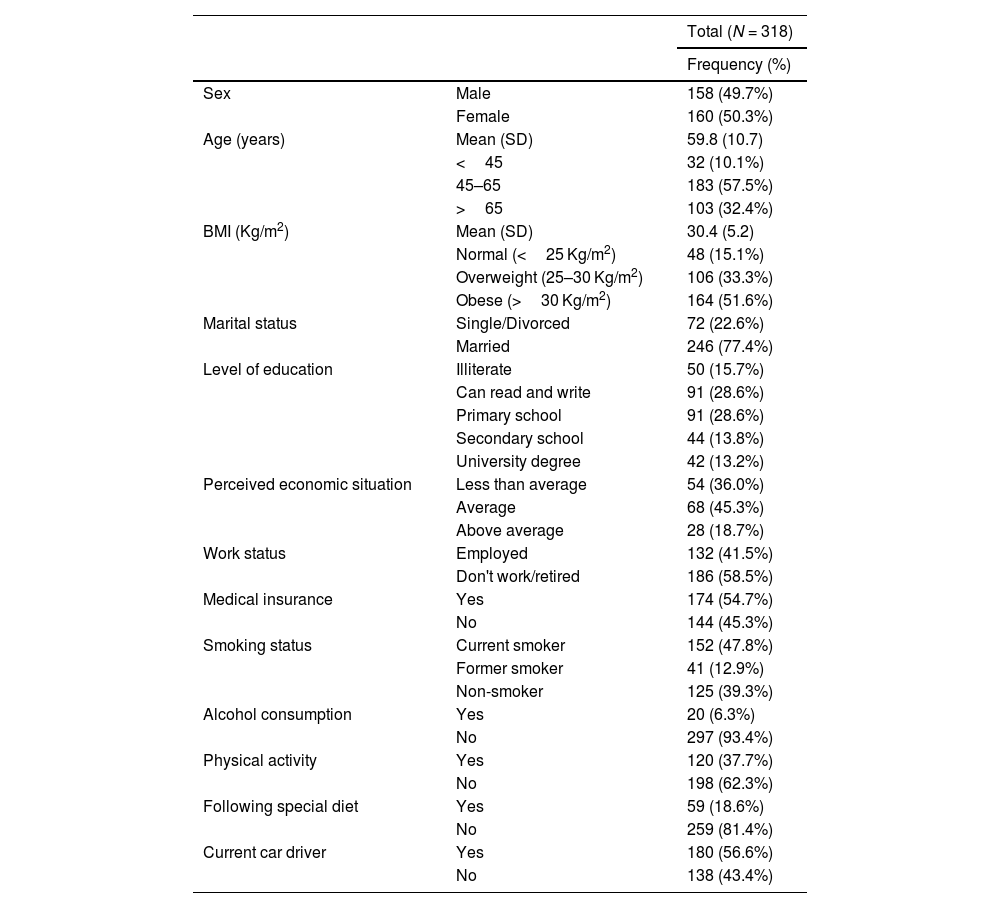

ResultsGeneral characteristics of the participantsOverall, 339 potential participants were approached, and 318 agreed to participate in the study (93.8%). The general characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. The sample was approximately equally distributed between males (49.7%) and females (50.3%). The mean age of the participants was 59.8 (10.7) years, with 57.5% between 45 and 65 years and 32.4% above 65 years of age. Over half of the patients (51.6%) were obese, 33.3% were overweight, and only 15.1% had a normal BMI. Most participants (77.4) were married; the rest (22.6%) were single, widowed, or divorced. Among others, 15.7% were illiterate, 28.6% finished primary school, and 13.2% had a university degree. Almost 59% did not work or were retired, and 41.5% were employed. Around 45% reported an average economic situation, while 36% had a below average situation. Around 55.0% of the participants reported having medical insurance, particularly public one. Forty-eight percent were current smokers, 12.9% were former smokers, and the remaining (39.3%) were non-smokers. Furthermore, 37.7% said they practiced sports regularly, 18.6% followed a special diet suggested by their doctor, and 56.6% reported being current car drivers.

Distribution of the general characteristics of the sample.

| Total (N = 318) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | ||

| Sex | Male | 158 (49.7%) |

| Female | 160 (50.3%) | |

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 59.8 (10.7) |

| <45 | 32 (10.1%) | |

| 45–65 | 183 (57.5%) | |

| >65 | 103 (32.4%) | |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | Mean (SD) | 30.4 (5.2) |

| Normal (<25 Kg/m2) | 48 (15.1%) | |

| Overweight (25–30 Kg/m2) | 106 (33.3%) | |

| Obese (>30 Kg/m2) | 164 (51.6%) | |

| Marital status | Single/Divorced | 72 (22.6%) |

| Married | 246 (77.4%) | |

| Level of education | Illiterate | 50 (15.7%) |

| Can read and write | 91 (28.6%) | |

| Primary school | 91 (28.6%) | |

| Secondary school | 44 (13.8%) | |

| University degree | 42 (13.2%) | |

| Perceived economic situation | Less than average | 54 (36.0%) |

| Average | 68 (45.3%) | |

| Above average | 28 (18.7%) | |

| Work status | Employed | 132 (41.5%) |

| Don't work/retired | 186 (58.5%) | |

| Medical insurance | Yes | 174 (54.7%) |

| No | 144 (45.3%) | |

| Smoking status | Current smoker | 152 (47.8%) |

| Former smoker | 41 (12.9%) | |

| Non-smoker | 125 (39.3%) | |

| Alcohol consumption | Yes | 20 (6.3%) |

| No | 297 (93.4%) | |

| Physical activity | Yes | 120 (37.7%) |

| No | 198 (62.3%) | |

| Following special diet | Yes | 59 (18.6%) |

| No | 259 (81.4%) | |

| Current car driver | Yes | 180 (56.6%) |

| No | 138 (43.4%) | |

Results are given in frequency (percentage) or Mean (SD: Standard Deviation). BMI: Body Mass Index.

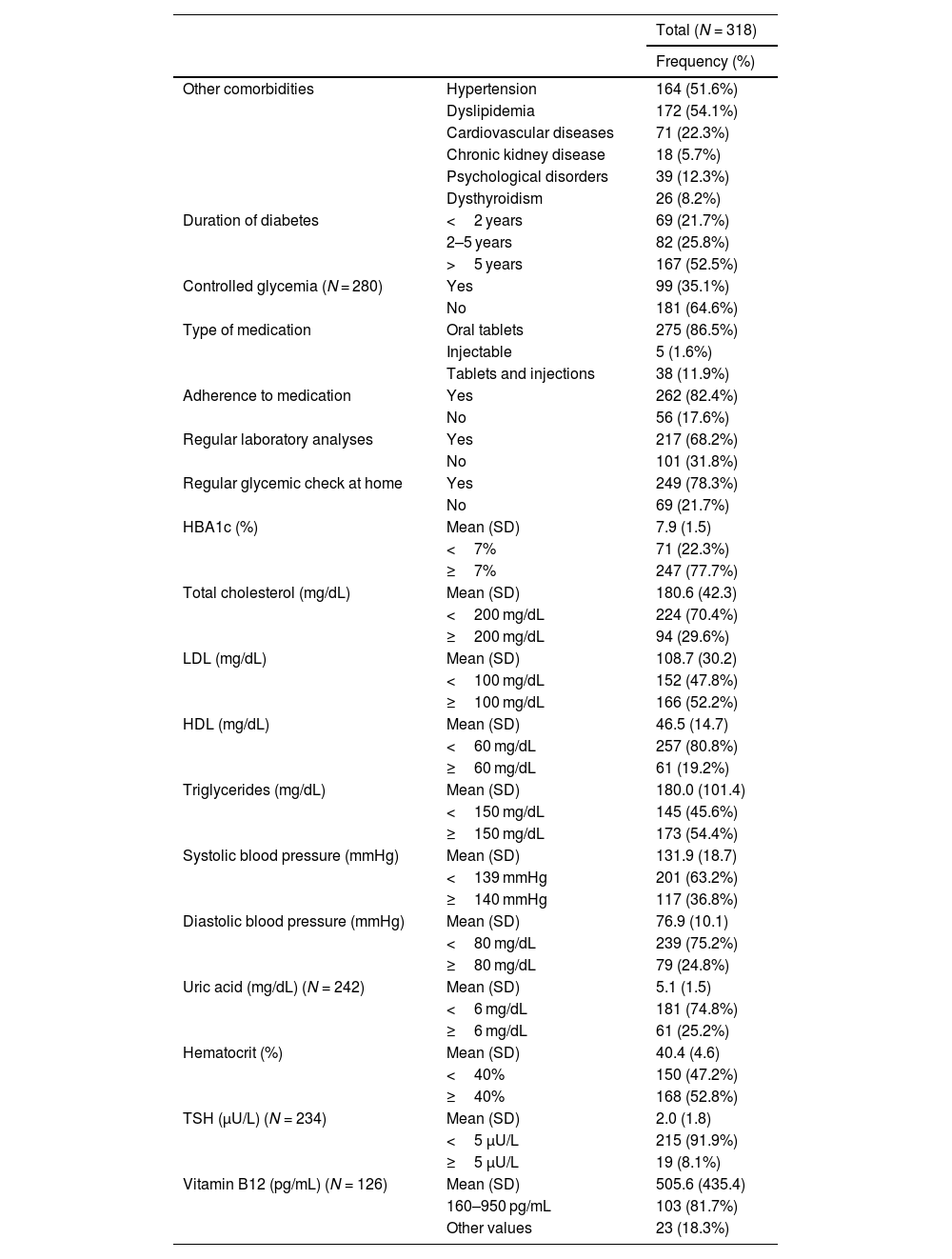

Table 2 shows the patients' medical history and latest laboratory test results. Dyslipidemia (54.2%) and hypertension (51.6%) were the most reported comorbidities among the participants, followed by cardiovascular diseases (22.3%) and psychological disorders (12.3%). Around half of the patients had diabetes for over 5 years (52.5%), and only 35.1% had their glycemia controlled. Regarding medication prescribed, most patients (86.5%) used oral tablets, and only 1.6% used injectable insulin. Treatment adherence was reported among the majority (82.4%), with 68.2% reporting regular laboratory analyses and 78.3% doing a regular glycemic check at home. The mean HBA1c value was 7.9 (1.5) %, with 77.7% of the patients having values ≥7%. Almost 70.0% of the sample had total cholesterol values <200 mg/dL, 52.2% had an LDL value above 100 mg/dL, and 80.8% had an HDL value below 60 mg/dL. Based on the doctor's examination during the day of the visit, 63.2% of the patients had a systolic blood pressure <139 mmHg and 75.2% had a diastolic blood pressure below 80 mmHg. As regards the other laboratory tests collected, 74.8% had blood uric acid values below 6 mg/dL, 47.2% had hematocrit values below 40%, 91.9% had their TSH values below 5 μU/L, and 81.7% had vitamin B12 values between 160 and 950 pg/mL.

Medical history and laboratory tests.

| Total (N = 318) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | ||

| Other comorbidities | Hypertension | 164 (51.6%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 172 (54.1%) | |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 71 (22.3%) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 18 (5.7%) | |

| Psychological disorders | 39 (12.3%) | |

| Dysthyroidism | 26 (8.2%) | |

| Duration of diabetes | <2 years | 69 (21.7%) |

| 2–5 years | 82 (25.8%) | |

| >5 years | 167 (52.5%) | |

| Controlled glycemia (N = 280) | Yes | 99 (35.1%) |

| No | 181 (64.6%) | |

| Type of medication | Oral tablets | 275 (86.5%) |

| Injectable | 5 (1.6%) | |

| Tablets and injections | 38 (11.9%) | |

| Adherence to medication | Yes | 262 (82.4%) |

| No | 56 (17.6%) | |

| Regular laboratory analyses | Yes | 217 (68.2%) |

| No | 101 (31.8%) | |

| Regular glycemic check at home | Yes | 249 (78.3%) |

| No | 69 (21.7%) | |

| HBA1c (%) | Mean (SD) | 7.9 (1.5) |

| <7% | 71 (22.3%) | |

| ≥7% | 247 (77.7%) | |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | Mean (SD) | 180.6 (42.3) |

| <200 mg/dL | 224 (70.4%) | |

| ≥200 mg/dL | 94 (29.6%) | |

| LDL (mg/dL) | Mean (SD) | 108.7 (30.2) |

| <100 mg/dL | 152 (47.8%) | |

| ≥100 mg/dL | 166 (52.2%) | |

| HDL (mg/dL) | Mean (SD) | 46.5 (14.7) |

| <60 mg/dL | 257 (80.8%) | |

| ≥60 mg/dL | 61 (19.2%) | |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | Mean (SD) | 180.0 (101.4) |

| <150 mg/dL | 145 (45.6%) | |

| ≥150 mg/dL | 173 (54.4%) | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | Mean (SD) | 131.9 (18.7) |

| <139 mmHg | 201 (63.2%) | |

| ≥140 mmHg | 117 (36.8%) | |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | Mean (SD) | 76.9 (10.1) |

| <80 mg/dL | 239 (75.2%) | |

| ≥80 mg/dL | 79 (24.8%) | |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) (N = 242) | Mean (SD) | 5.1 (1.5) |

| <6 mg/dL | 181 (74.8%) | |

| ≥6 mg/dL | 61 (25.2%) | |

| Hematocrit (%) | Mean (SD) | 40.4 (4.6) |

| <40% | 150 (47.2%) | |

| ≥40% | 168 (52.8%) | |

| TSH (μU/L) (N = 234) | Mean (SD) | 2.0 (1.8) |

| <5 μU/L | 215 (91.9%) | |

| ≥5 μU/L | 19 (8.1%) | |

| Vitamin B12 (pg/mL) (N = 126) | Mean (SD) | 505.6 (435.4) |

| 160–950 pg/mL | 103 (81.7%) | |

| Other values | 23 (18.3%) | |

Results are given in frequency (percentage) or Mean (SD: Standard Deviation). HBA1c: Glycated hemoglobin A1c; LDL: Low-density lipoprotein; HDL: High-density lipoprotein; TSH: Thyroid stimulating hormone.

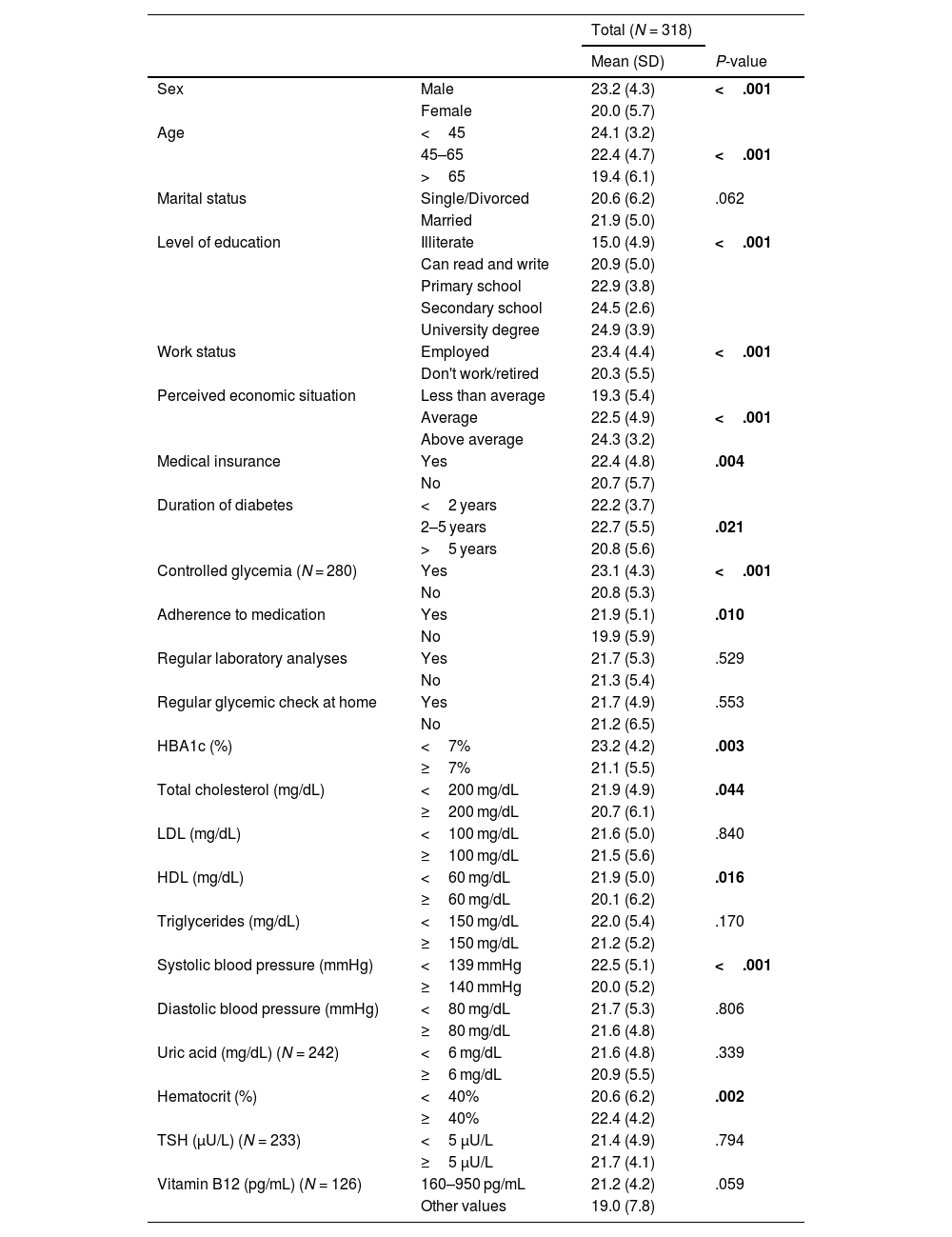

Based on the MMSE test results, the patients' mean score was 21.6 (5.3), distributed as follows: 217 patients (68.2%) had possible cognitive impairment, and 101 (31.8%) had a normal cognitive function. Table 3 shows the association between the characteristics of the participants and the cognitive function scores. Significantly lower scores were noted among females (20.0) than males (23.2; P < .001). The increase in age was found to be significantly affecting the cognitive function scores of patients, with higher scores among those below 45 (24.1) and lower ones among those between 45 and 65 years (22.4) and above 65 (19.4; P < .001). The level of education also directly impacted the cognitive function scores, where illiterate had significantly lower scores (15.0) compared to those with advanced education (secondary school (24.5) and university graduates (24.9; P < .001)). A higher cognitive function score increased per increase in perceived economic situation with the lowest score for those with a below average situation (19.3 vs. 22.5 and 24.3; P < .001). Furthermore, those employed (23.4 vs. 20.3; P < .001) and those with medical insurance (22.4 vs. 20.7; P = .004) had significantly lower scores than others. Participants with diabetes for more than 5 years (20.8) and those with uncontrolled glycemia (20.8) had lower cognitive function than patients diagnosed more recently (22.2; P = .021) or those with controlled glycemia (23.1; P < .001). Moreover, those reporting adherence to treatment (21.9; P = .010) and those with an HBA1c value below 7% (23.2; P = .003) had higher scores than others. As regards the association between the participants' cognitive function and other laboratory tests, a cognitive decline was found among those with total cholesterol ≥200 mg/dL (20.7 vs. 21.9; P = .044), a systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg or more (20.0 vs. 22.5; P < .001), and hematocrit levels below 40% (20.6 vs. 22.4; P = .002).

Association between the cognitive function of patients with diabetes and their general characteristics.

| Total (N = 318) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | P-value | ||

| Sex | Male | 23.2 (4.3) | <.001 |

| Female | 20.0 (5.7) | ||

| Age | <45 | 24.1 (3.2) | |

| 45–65 | 22.4 (4.7) | <.001 | |

| >65 | 19.4 (6.1) | ||

| Marital status | Single/Divorced | 20.6 (6.2) | .062 |

| Married | 21.9 (5.0) | ||

| Level of education | Illiterate | 15.0 (4.9) | <.001 |

| Can read and write | 20.9 (5.0) | ||

| Primary school | 22.9 (3.8) | ||

| Secondary school | 24.5 (2.6) | ||

| University degree | 24.9 (3.9) | ||

| Work status | Employed | 23.4 (4.4) | <.001 |

| Don't work/retired | 20.3 (5.5) | ||

| Perceived economic situation | Less than average | 19.3 (5.4) | |

| Average | 22.5 (4.9) | <.001 | |

| Above average | 24.3 (3.2) | ||

| Medical insurance | Yes | 22.4 (4.8) | .004 |

| No | 20.7 (5.7) | ||

| Duration of diabetes | <2 years | 22.2 (3.7) | |

| 2–5 years | 22.7 (5.5) | .021 | |

| >5 years | 20.8 (5.6) | ||

| Controlled glycemia (N = 280) | Yes | 23.1 (4.3) | <.001 |

| No | 20.8 (5.3) | ||

| Adherence to medication | Yes | 21.9 (5.1) | .010 |

| No | 19.9 (5.9) | ||

| Regular laboratory analyses | Yes | 21.7 (5.3) | .529 |

| No | 21.3 (5.4) | ||

| Regular glycemic check at home | Yes | 21.7 (4.9) | .553 |

| No | 21.2 (6.5) | ||

| HBA1c (%) | <7% | 23.2 (4.2) | .003 |

| ≥7% | 21.1 (5.5) | ||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | <200 mg/dL | 21.9 (4.9) | .044 |

| ≥200 mg/dL | 20.7 (6.1) | ||

| LDL (mg/dL) | <100 mg/dL | 21.6 (5.0) | .840 |

| ≥100 mg/dL | 21.5 (5.6) | ||

| HDL (mg/dL) | <60 mg/dL | 21.9 (5.0) | .016 |

| ≥60 mg/dL | 20.1 (6.2) | ||

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | <150 mg/dL | 22.0 (5.4) | .170 |

| ≥150 mg/dL | 21.2 (5.2) | ||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | <139 mmHg | 22.5 (5.1) | <.001 |

| ≥140 mmHg | 20.0 (5.2) | ||

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | <80 mg/dL | 21.7 (5.3) | .806 |

| ≥80 mg/dL | 21.6 (4.8) | ||

| Uric acid (mg/dL) (N = 242) | <6 mg/dL | 21.6 (4.8) | .339 |

| ≥6 mg/dL | 20.9 (5.5) | ||

| Hematocrit (%) | <40% | 20.6 (6.2) | .002 |

| ≥40% | 22.4 (4.2) | ||

| TSH (μU/L) (N = 233) | <5 μU/L | 21.4 (4.9) | .794 |

| ≥5 μU/L | 21.7 (4.1) | ||

| Vitamin B12 (pg/mL) (N = 126) | 160–950 pg/mL | 21.2 (4.2) | .059 |

| Other values | 19.0 (7.8) | ||

Results are given in terms of Mean (SD: Standard Deviation). P-values<.05 are presented in bold. HBA1c: Glycated hemoglobin A1c; LDL: Low-density lipoprotein; HDL: High-density lipoprotein; TSH: Thyroid stimulating hormone.

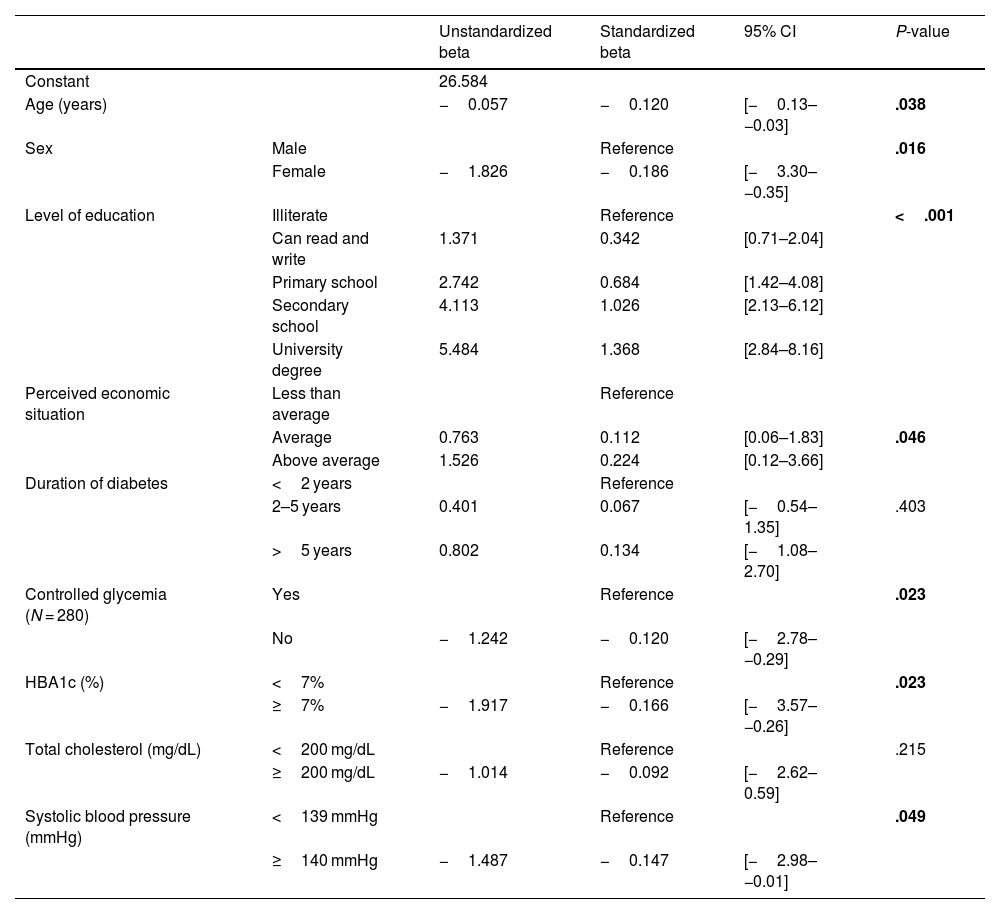

After adjusting for covariates, a significantly lower cognitive function score was found per increase of 1 year of age (b=−0.120, CI (−0.13, −0.03); P = .038). Females had a score of 0.186 less than males (CI (−3.30, −0.35); P = .016), and an increase of a factor of 0.342 was found between the levels of education (CI (0.71–2.04); P < .001). Higher economic situation was associated with a significantly better cognitive function (b = 0.112, CI (0.06, 1.83); P = .046).

Patients with uncontrolled glycemia had a lower score of 0.120 than those with controlled glycemia (CI (−2.78, −0.29); P = .023), and those with HBA1c values ≥7% had significantly lower cognitive function scores (b=−0.166 (CI: −3.57, −0.26); P = .023). Moreover, having a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg decreased the cognitive function score by a factor of 0.147 (CI (−2.98, −0.01); P = .049) (Table 4). A significant regression analysis was found (F (1,82)=8.511, P < .001) with an R2 of 0.386. The corresponding equation is presented below:

The combined effect of the predictors affecting the cognitive function scores among patients with diabetes.

| Unstandardized beta | Standardized beta | 95% CI | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 26.584 | ||||

| Age (years) | −0.057 | −0.120 | [−0.13–−0.03] | .038 | |

| Sex | Male | Reference | .016 | ||

| Female | −1.826 | −0.186 | [−3.30–−0.35] | ||

| Level of education | Illiterate | Reference | <.001 | ||

| Can read and write | 1.371 | 0.342 | [0.71–2.04] | ||

| Primary school | 2.742 | 0.684 | [1.42–4.08] | ||

| Secondary school | 4.113 | 1.026 | [2.13–6.12] | ||

| University degree | 5.484 | 1.368 | [2.84–8.16] | ||

| Perceived economic situation | Less than average | Reference | |||

| Average | 0.763 | 0.112 | [0.06–1.83] | .046 | |

| Above average | 1.526 | 0.224 | [0.12–3.66] | ||

| Duration of diabetes | <2 years | Reference | |||

| 2–5 years | 0.401 | 0.067 | [−0.54–1.35] | .403 | |

| >5 years | 0.802 | 0.134 | [−1.08–2.70] | ||

| Controlled glycemia (N = 280) | Yes | Reference | .023 | ||

| No | −1.242 | −0.120 | [−2.78–−0.29] | ||

| HBA1c (%) | <7% | Reference | .023 | ||

| ≥7% | −1.917 | −0.166 | [−3.57–−0.26] | ||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | <200 mg/dL | Reference | .215 | ||

| ≥200 mg/dL | −1.014 | −0.092 | [−2.62–0.59] | ||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | <139 mmHg | Reference | .049 | ||

| ≥140 mmHg | −1.487 | −0.147 | [−2.98–−0.01] | ||

Linear regression model of the cognitive function score. Results are given in standardized beta and 95% CI: Confidence Interval. P-values <.05 are presented in bold. HBA1c: Glycated hemoglobin A1c.

The present study aimed to evaluate cognitive impairment in patients with diabetes and the factors associated with cognitive decline. Around 68% of the patients had possible cognitive impairment, substantially higher than the prevalence in other studies performed in similar settings.17 This can be associated with general or specific factors in Lebanon, such as the concurrence of the pandemic and the economic crisis with the data collection period. The study sample was equally distributed between males and females. In contrast, some research on the relationship between diabetes and cognitive impairment included more males,18 while other studies had more females.19 Sex was found to be significantly associated with lower cognitive function scores among females in this study, as in the previously conducted research and a recently published study reporting a higher risk of accelerated cognitive decline among females with type 2 diabetes.20 This can be due to the potential role of oxidative stress as a link between diabetes and cognitive dysfunction found to be higher among females.19 Older age was found to be associated with lower cognitive function, particularly those older than 65 years had significantly lower cognitive scores than younger participants. This finding was also reported in other studies conducted among patients with chronic diseases,21 namely with diabetes.22 Education was found to be associated with the patients' cognitive function, with lower scores among those with lower education. This can be explained by the fact that those with higher education levels were more adherent to treatments and doctors' instructions and were less prone to diabetes-related complications.14,23 A recently published study reported a slower decline in global cognition, memory, and attention among high-educated patients,24 making those with lower education more vulnerable to cognitive decline. A better economic situation was also associated with increased cognitive function. Given that the healthcare system in Lebanon is mostly privatized, and most payments are out-of-pocket,13 those with medical insurance and better financial status can cover their in-hospital treatment, and part of their pharmaceutical and medical bills, leading to a better adherence.

Diabetes duration was related to cognitive decline, with an increased risk among those diagnosed from more than 5 years, in agreement with a previous study using the same assessment.25 Furthermore, cognitive function was aggravated with increased duration (10–15 years),26 possibly since micro- and macrovascular complications, oxidative stress, and insulin resistance increase over time and can induce neuronal damage.27 Among the laboratory tests, having HBA1c values of 7% or more, total cholesterol levels ≥200 mg/dL, and hematocrit values below 40% were linked to cognitive decline. Higher HBA1c levels may promote the accumulation of advanced glycation products in the brain leading to a structural and functional abnormality,27 a result also reported in a recent meta-analysis.28 Patients with higher total cholesterol levels had lower cognitive scores, possibly due to the increased sensitivity of neurons to fatty acids, which might induce neurodegenerative diseases.29 In contrast, a recent study highlighted a possible correlation between high cholesterol levels and maintained cognitive function.30

Despite being the first study performed in Lebanon to evaluate the association between the cognitive function of patients with diabetes and their characteristics, it has several limitations. Laboratory test results were retrieved from the patients' files at the clinics based on their last performed exam, which can differ between patients. Recall bias might have been induced since a self-reported survey was used for the collection of the socio-demographic characteristics of the patients, which can be biased if the patients had low cognitive function scores to answer these questions with precision. Furthermore, some variable can be related inducing a possibility of being confounding factors, such as sex and educational levels, and economic situation and glycemic control. Therefore, we considered the adjusted model in the multivariable analysis. Interviewer bias was reduced since the data collectors were uniformly trained and did not interfere with the patient's answers. Moreover, data coding and analysis were performed by a different researcher, which minimized the subjectivity of data collectors. Although the sample size was fairly enough to perform multivariate analysis, patients were recruited from only 2 clinics located in the South of Lebanon, which may affect the extrapolation of the results to other settings. A nationwide longitudinal study is recommended to allow better external validity and representativeness of Lebanon. Based on the findings of this study, endocrinologists, the medical team, and health plan providers can develop and implement tailored care plans targeting those most vulnerable.

ConclusionA high prevalence of cognitive impairment was reported among patients with diabetes. Among others, lower cognitive function scores were associated with female sex, older age, unemployment, and lower level of education. These scores were significantly higher among patients with controlled glycemia, an HBA1c <7%, a systolic blood pressure <139 mmHg, and hematocrit levels of 40% or more. These factors should be considered for treatment management and glycemic control. This study's findings can help detect patients at risk of developing cognitive decline early, allowing an early referral to a neurologist or neuropsychologist to prevent complications.

Ethics approval and consent to participateAfter reviewing the study protocol, questionnaire, and consent form, the institutional review board of the faculty of pharmacy of the Lebanese University approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

AcknowledgmentsNot applicable.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materialsNot applicable.

Declaration of Competing InterestNone.