Over the last two-decade, major efforts have been underway to improve the standard of care at the end of life. Nevertheless, recent evidence has highlighted that many patients still receive overtreatment or inappropriate support to face dying in all its complexity. These scenarios may increase thoughts of death that often occur during the course of terminal illnesses requiring prompt and adequate interpretations and interventions. This suggests the need for a change in treating dying patients along with a clear understanding of the root causes of requests for euthanasia. In this regards, we propose a protocol for a shared end-of-life care plan aimed at ensuring a quality accompaniment toward natural death. It involves the patient and their family, as well as healthcare providers in a flexible work plan articulated in two phases concerning respectively pre-mortem and post-mortem actions. It offers a clear and systemic template for care in preparation for natural death, which takes into consideration healthcare duties and the patient as a person.

Desde hace dos décadas, se han realizado muchos esfuerzos para promover el cuidado estandarizado al final de la vida. No obstante, existen evidencias recientes que señalan que muchos pacientes todavía reciben tratamiento inapropiado para enfrentar el proceso de morir en toda su complejidad. Esos escenarios aumentan los pensamientos sobre la muerte en el proceso de la enfermedad terminal lo cual requiere prontas y adecuadas interpretaciones y acciones. Ésto sugiere la necesidad de cambiar el manejo de los pacientes en proceso de muerte comprendiendo claramente las raíces del porqué solicitan eutanasia. En éste sentido, nosotros proponemos un protocolo de cuidados de fin de vida en forma compartida que asegure la calidad de acompañamiento frente a la muerte natural. Este modelo implica al paciente y la familia, así como a los proveedores de salud en un plan flexible de trabajo articulado en dos fases de acciones, la pre-mortem y la post-mortem. Este modelo ofrece una clara y sistémica base de cuidado en preparación para la muerte natural, que toma en consideración las obligaciones del personal de salud y al paciente como persona.

“Death comes in any case, but its arrival is encrusted with untold woe. When death is the inevitable result of a chronic and incurable disease, it is often kinder not to impede it with heroic measures but to manage its approach with common sense and compassion” (Lown, 1999, p. 269). These suggestive words used by Lown in his famous book The Lost Art of Healing are an appropriate prolog to this study, because they touch on three important issues: the inevitably of death; death as a source of much apprehension and suffering; the need for an appropriate plan to manage end-of-life care. Although death as the natural evolution of life concerns everyone, people are often reluctant to face their being mortal seriously, along preferring to focus on an increased confidence in scientific and technological advances in medicine. Moreover, recent research has shown that care and support received by patients in the last phase of life are not always appropriate. This mostly involves inadequate treatment decisions, especially overtreatment, and poor communication (Bolt, Pasman, Willems, & Onwuteaka-Philipse, 2016; Winkler & Heußner, 2016). Gawande, during his career as a surgeon, turned his attention to some basic errors made by physicians treating terminally ill patients. Specifically, he found that many of them approached these situations as if they were a mere matter of “facts and figures”, rather than trying to understand what is most important: what are the biggest fears and concerns of patients in their specific circumstances, along with an effort to use this information to make decisions (Centeno, 2015, p. 156; Gawande, 2014, pp. 233–234). Finding effective ways to improve care for patients near the end of life must become a priority, it being understood that “taking care” requires clear and shared approaches that go beyond fragmented indications and a mere medicalization of suffering and dying.

Taking previous remarks on death and dying concerning patients with advanced and terminal diseases as our starting point, we address the main current approaches to end-of-life care. The primary aim of this paper is to consider how best to ensure that patients and their families, together with the team involved in the care process, can work jointly to achieve the goal of a clear and professional accompaniment to the end of life. In this regard, we discuss a proposal for a natural death protocol (NDP) as a preventive care plan because it aims to prevent uncertainty, confusion and avoidable suffering in facing this natural event.

Remarks on death and dying: clarifying critical issues at the end of life“People really die and no longer one by one, but in a large number, often ten thousand in one day. It is no longer an accident” (Freud, 1918, p. 47). Death like birth is an inseparable aspect of life. It is not something foreign that sooner or later everyone will possess; death belongs to the category of being and not of having, and hence it is a natural occurrence of existence and not something accidental (see Heidegger, 1962). Despite its inevitability, death remains a problem for people, a stark reality that not everyone is ready and prepared to face. Although thinking of birth almost always arouses positive attitudes and emotions, the same cannot be said when we refer to death and the process of dying. There is a vast literature attesting death anxiety and fear that covers different aspects of the subject (see, for example Abdel-Khalek, 2002; Corwin, 2005; Gawande, 2014; Kübler-Ross, 2009; Lehto & Stein, 2009; Russell, 2014). These studies typically address specific components among which the following stand out:

- •

the fact of death (death as something unknown because it goes beyond experiential knowledge and hence escapes a scientific understanding of its complexity);

- •

the process of dying (annihilation of self, loss of function, dependence on other, incapacity to tolerate the pain involved, overtreatment, fear of being alone, fear of loss of loved ones, apprehension about how to face the process of dying, apprehension about the financial cost of dying, fear about the incapacity for self-realization and expression);

- •

the consequences of death (interruption of the pursuit of goals, negative impact on survivors);

- •

what happens after death (concern about the existence of an afterlife, concern about the meaning of one's own life project).

These components well summarize the basic needs of every individual, as they have been expressed by Maslow (1954), that is physiological needs, safety and security, love and belonging, self-esteem and self-realization which are threatened and obliterated in those situations of chronic diseases that lead to the end of life where death does not come suddenly or unexpectedly but is a slow and very painful process. In these cases, patients are confronted with an experience that implies living death, and this event, in view of what has just been mentioned, in turn, requires systemic support (see Jordan, 1973) centered on the patient as a person and aimed at creating those multidimensional conditions for a good accompaniment to natural death. The need for a clear systemic plan for a peaceful death today is more than ever indispensable in the face of the significant developments in biotechnology. These contribute paradoxically to making the accompaniment of end of life confused because of their heterogeneity and their offer of an apparent power to extend life and postpone death.

As stressed by Bellino: “There is silence when it comes to the essential matters, to what is really important. […]. But there is a time when this silence on the essential matters cannot be kept without forgetting the sincerity and truth duty and without risking the essential matter itself” (2011, pp. 21–22). That is, in these situations the not offering a clear path to die well, deferring everything to fragmented indications (pain therapy, alternating hospitalizations, resuscitation, etc.), throws the patient into uncertainty, doubt and fear that will gradually increase by appealing to his/her imagination and inner resources. Warren Reich has pointed out that in contemporary bioethics on the end of life greater attention is paid to the question of when to die and consequently to assisted suicide and euthanasia than to the question of how we should effectively take care to those who are dying (2003, p. 35). In other words, these matters require an adequate attention because addressing apprehensions and suffering associated with the end of life only in terms of euthanasia implies the risk of reducing to questions of legacy and illicitness issues whose human richness and complexity go beyond this reductive view. In order to break the silence mentioned above, it is useful to say a few words about euthanasia proposals because we believe that much of their appeal today lies in offering clearer information relating to the procedure by which one comes to death. This procedural transparency offers in a way the impression of keeping under control the event of death that instead, by its nature, eludes human grasp.

From the nosographic approach to the prevention of euthanasiaInternational medicine has employed nosographic classification for several years to identify diseases according to different criteria. From a nosographic point of view, in our opinion, the request for euthanasia can be seen as a suicidal impulse when it is described as “intentional selfharm through medical intervention” (see Tambone, Sacchini, & Cavoni, 2008). For, if we compare euthanasia with suicide it emerges that these acts are almost overlapping in relation to the aspects listed below:

- •

the subject of the action (the person who wants to die takes the action initiative);

- •

the fact of the act (while suicide is an act not mediated by other people even though it may foresee their participation, euthanasia is an mediated suicide; however in both cases there is a desire to kill oneself through the choice of a tool considered to be the most appropriate);

- •

the scope of the act (the action is aimed at putting an end to a state of suffering which is lived as unsustainable and which can vary in its nature).

The above mentioned nosographic framing of euthanasia allows us to conclude that the request for euthanasia falls within the physician's and nurse's competence with respect to its prevention. In this respect, the whole process that caused an undesirable event needs to be analyzed in order to be prevented. In the specific case of euthanasia, we stress the importance of identifying and taking action at the level of the root causes of this event in so far as, according to the Root Causes Analysis methodology often applied also in medicine (Brennan et al., 1991), interventions aimed only at the immediate and deep causes delay but do not prevent the adverse effect.

Based on this methodological framework, we carried out two studies in several hospitals specialized in chronic degenerative diseases in New York and Italy respectively in 1998 and in 2005. The quantitative detection of the request for euthanasia and the knowledge of motivations based on their frequency were addressed (Tambone et al., 2008, pp. 28–45). In these studies euthanasia is considered a matter of heath and therefore we tried to identify the root causes in order to develop a real form of prevention aimed at promoting the quality of life. Broadly speaking, the results showed that all requests for euthanasia were motivated: death was not desired as the ultimate aim but as the last way out of a series of problems related to the disease that were no longer solvable for the patient. They referred to three main factors:

- 1.

the feeling of being a burden on the family;

- 2.

physical suffering;

- 3.

reactive depression.

These data, seemingly obvious, are significant in opening a breach in that wall of silence that endangers the essential. They suggest the need to develop an integrated care-giving that is also a useful starting point for a “medical treatment of the request for euthanasia”. In other words “it is how we can build a health care system that will actually help people achieve what's most important to them at the end of their life” (Gawande, 2014, p. 155) and this involves priorities that go beyond simply prolonging their life or a false desire to die.

Today, attempts to move in this direction are present in the world of healthcare, but the effort of many, especially of those who directly face these experiences, makes clear the further need for stronger support system connected with scientific research. To better explain what this means, we will briefly review the current approach to the end of life, particularly palliative sedation and proposals for advance care planning.

Current approaches to end-of-life careThe literature on end-of-life care agrees in showing that thoughts of death may emerge along the course of chronic diseases and that they bring about a worse outcome. At the same time, it is also known that the desire to die may decrease significantly in the presence of adequate care and relational support, especially from the people closest to the patient (Tambone et al., 2008, p. 278). In this perspective, the request for euthanasia should not be taken by clinicians as an ideological position to oppose or favor, but rather as a need to be interpreted and satisfied, under specific conditions, with regard to the causes that determine it. Specifically proposals of euthanasia are “often a cry for help on the part of a person not yet ready to die, despairing of securing humane attention and relief of suffering in any other way […]. They sound an alarm about the needless pain and suffering at the end of life that is now the lot of so many in our society, meant to call attention to what more adequate treatment would mean” (Bok, 1998, p. 136).

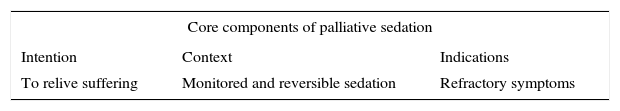

Over the last two decades, there have been significant advances about how to face the end of life through a set of interventions better known as palliative care (PC). In accordance with WHO's definition, we can identify key components of this concept described as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychological and spiritual” (World Health Organization, 2016). Thus the aim of palliative care is “neither to hasten nor postpone death” but to “enhance quality of life” through multidimensional support which, in turn, implies an interdisciplinary team. Consistent with these goals, one of the key aspects of palliative care refers to the possible use of specific sedative drugs aimed at reducing the burden of pain caused by advanced and chronic diseases. Specifically, this therapeutic option reduces the level of the patient's consciousness along with the perception of those symptoms that, especially in the last stages of life, cannot be adequately handled because available treatments are ineffective or associated with unbearable side effects (Carassiti, De Benedictis, Comoretto, Vincenzi, & Tambone, 2014, p. 39). Such clinical practice is commonly referred to as “terminal sedation” which, however, has often been criticized because it easily gives rise to misunderstanding. In fact the adjective “terminal” can be understood both as a prognostic criterion referring to the course of illness and as the definition of the irreversibility of sedation, with the risk to identify this clinical procedure with euthanasia, and therefore not reflecting its real intention (De Benedictis, Vincenzi, & Tambone, 2008, p. 4; see also, Bonito et al., 2005). For these reasons, we propose the following alternative expressions: “palliative sedation (PS)” and “terminal palliative sedation (TPS)”. The first refers to the monitored use of medication aimed at relieving refractory symptoms, such as pain, delirium, dyspnea, convulsion, by inducing a state of decreased or absent awareness as much as is ethically acceptable for the patient, family and health care providers involved (see, Cherny et al., 2009). In line with the core components of the concept of PS, as shown in Table 1, the second expression denotes the same practice administered to patients with a life expectancy of ninety days, who cannot be treated with a specific therapy and with a Karnofsky index equal to or less than 50, although the definition of “terminal ill” still appears problematic, as Hui has well shown (Hui et al., 2014, p. 4).

TPS can be intermittent or continuous, but by virtue of its clear therapeutic goal to provide a response to extreme suffering in a natural way, it must in no way be confused with the use of sedation to prepare someone to be killed, as in euthanasia. Although the importance of TPS is evident, taking care of a patient in the final stages of life, as mentioned before, requires wider and deeper modes of expression and action, for example communication and relational skills, as well as the ability to plan treatments and care interventions for these specific situations. This means that TPS is only one facet of a broader, systemic accompanying program characterized by choices and aims, in accordance with the patient's wishes and with respect for their preparation for natural death. This perspective, on the one hand, keeps palliative care from being seen as something similar to medicalization of suffering and death (see, Di Mola, 2001); on the other hand, it leads to the development of increased sensitivity among health-care givers toward those who are approaching death.

A recent explorative study among patients and their families about care in the last phase of life shows that “appropriate care” is a broad term encompassing many different elements such as supportive care, treatment decision, location of care, patient's wishes, good communication. In addition, because patients have different needs that can change over time, healthcare providers need to discuss all relevant options repeatedly and help patients and their families to articulate aims and preferences before decision are made (Bolt et al., 2016, p. 9). On the strength of the results of this study, we have worked out a list of characteristics of the recently updated concept of Advance Care Planning (ACP), which includes patient involvement in the process of care. Specifically, unlike traditional academic assumptions about advance directives, such as living wills (Singer, Martin, & Lavery, 1998, p. 879), it must now be recognized that:

- •

ACP is not only for preparing for incapacity but also for death;

- •

ACP is not based solely on autonomy and the exercise of control, but also on personal relationships and the relieving of burdens placed on others;

- •

ACP is not limited to completing written advance directives forms but needs to be seen as a social process;

- •

ACP does not occur solely within the context of the physician–patient relationship but also within relationships with close loved one. Summarizing, ACP goes beyond the mere implementation of written advance directives with legal value, insofar as it includes a social process in which the patient's wishes are considered in a broader perspective and discussed also with close family members. This concept has gradually become wider and more detailed with regard to its aims and contents. As Centeno well clarifies, ACP “is the process of working with a patient to design his health care, foreseeing future situations and making decisions based on his wishes and preferences on how to proceed accordingly in situations that may take place. […]. The substantial difference between ACP and living will is that ACP is a process of reflection that necessarily needs information and communication from health professionals in combination with the patient. They aim at providing appropriate care rather than limiting life-sustaining treatments” (2015, pp. 140–141). In other words, ACP is a step-by-step relational process and not a stand-alone act or document in which end-of-life care is not occasional, randomly continuous, or sporadic, but the result of a shared schedule attentive to scientific standards as well as to values and preferences involved in each specific situation. The ACP process that should always involve access to palliative care (Centeno, 2015, p. 149), should consider:

- •

the illness and its prognosis;

- •

relevant values and beliefs;

- •

general and specific preferences regarding treatment and care;

- •

interventions authorized or rejected;

- •

questions related to death;

- •

appointment of representative.

Conceptualizing ACP in this way, as a clear and social process, means knowing unequivocally what to do to better ensure quality of care for dying patients in all its complexity.

The natural death protocol (NDP)Drawing upon these current approaches to end of life care, we propose a first draft of a protocol, usable in healthcare institutions, to accompany the patient toward a natural death. We believe that care interventions at the end of life, such as TPS, will take on their full meaning only when they become an essential aspect of a shared protocol. In this way, they acquire an important value as key components to serve a good and peaceful end of life. As we have already shown, patients at the end of life have different needs, for example physical, psychological, social, spiritual, legal, to prepare for death. It is not unusual that while patient and their families wish that their needs have witness, there is often hope for further cure or life-prolonging interventions. Therefore, “care often focusses on multiple goals simultaneously; palliation, life-prolongation and even cure. Unfortunately, these aims are not always compatible; […]. At the same time, care can also be insufficient in fulfilling the patient's needs. For instance, some groups of patients may have limited access to palliative care or receive lower quality curative care” (Bolt et al., 2016, pp. 1–2).

Our first proposal for a NDP aims to provide guidance and clarity of information on key aspects of the process of care and accompaniment for the patient in their last hours/days of life, so as to avoid their living the experience of dying with fear, confusion and distress that derived from not knowing what is going to happen. The NDP might also be useful from a legislative point of view, especially when it comes to law-making on end-of-life issues. Therefore, it is appropriate to think of the protocol as a road map that coordinates and specifies a range of integrated actions to ensure best clinical practices for a good natural death. The proposal and initiation of the NDP could be started by the ethics consultant when the clinical situation has been assessed as irreversible.

Talking about a protocol for a good death may seem unacceptable at first glance, especially for those who advocate the sacredness of life until natural death. In this regard, it is important to make clear from the outset that what we propose is not a procedure to kill the patients but to accompany them toward natural death, that is a death not induced, with competence, professional clinical support, transparency, service attitude and sharing. The protocol we propose is addressed to patients with terminal diseases and their families as well as to the multidisciplinary team involved in the process of care in order to work together for a better rationalization of the patient's death. Contrary to the idea of a unilateral autonomy whereby the patient is alone in documenting the directives, the NDP offers a shared planning of end of life care. The ever increasing popularity of social networks, though problematic, shows that sharing is strongly desired, as testified as well by people's continuous requests for community approval for their own choices.

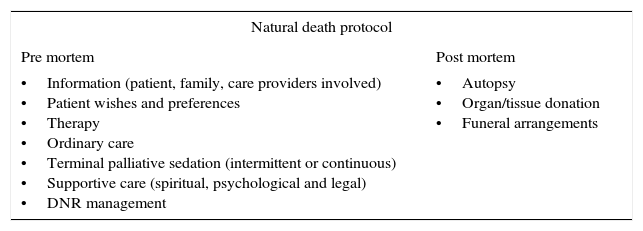

From a procedural point of view, as Table 2 shows, the NDP involves an action plan in two phases concerning respectively pre-mortem and post-mortem items. They are not to be considered necessarily in chronological order and are opened to variances and further implementations. Nevertheless, the protocol provides operational indications that seem compelling and shareable both at the relational level and systemic level because they are attentive to the multidimensional instances so often linked to the care planning at the end of life. In other words, the NDP is a flexible path to adequately support what may take place and what matters in situations that imply preparing and planning for dying as a personal experience lived within a context of relationships (Russell, 2014, p. 997).

Key points for a natural death protocol.

| Natural death protocol | |

|---|---|

| Pre mortem | Post mortem |

| •Information (patient, family, care providers involved) •Patient wishes and preferences •Therapy •Ordinary care •Terminal palliative sedation (intermittent or continuous) •Supportive care (spiritual, psychological and legal) •DNR management | •Autopsy •Organ/tissue donation •Funeral arrangements |

Broadly speaking, NDP items deal with (a) clear and appropriate information about the patient's clinical situation for a prompt and appropriate decision making; (b) documentation of wishes and presences that are essential for a good dying and death (quality of life, ability to communicate, level of pain control, where to spend the final days, importance of family, etc.); (c) periodic discussion covering interventions to authorize or reject, support to treat complications, maintaining of hydration and feeding, pain therapy and relief of refractory symptoms and other potential scenarios; (d) humanization of death (avoid loneliness and sense of neglect, establish good communication, efforts for an early detection of symptoms which lead to desire for euthanasia, attention and support to prevent family breakdown syndrome, appointment of representative, wishes be carried out in the last moments of life, etc.); (e) decisions about cardiopulmonary resuscitation (Centeno, 2015; Fine, Yang, Spivey, Boardman, & Courtney, 2016; Tambone et al., 2008).

NDP links end-of-life issues with after-death issues, such as autopsy under certain conditions (for example, to help others, to shed light on own death), organ/tissue donation and funeral arrangements, that often are sources of concern and interest among patients and their relatives (Fine et al., 2016; Gawande, 2014). These important topics are influenced by values and beliefs and, therefore, deserve a shared assessment in view of a peaceful death.

ConclusionToo many people “die unnecessarily bad deaths - deaths with inadequate palliative support, inadequate compassion, and inadequate human presence and witness. Deaths preceded by a dying marked by fear, anxiety, loneliness, and isolation. Deaths that efface and deny individual self control and choice” (Jennings et al., 2003, p. S3). Although much progress has been made with regard to care for dying patients, we need to be more prepared to deal with the concerns and needs of patients and families so that a good natural death can take place. This requires a clear care framework that should be available to everyone, when it is thought that patients are within a terminal clinical situation. Proposing a shared protocol for a natural death could represent a useful suggestion to guide clinical practice in a very difficult time by preparing patients and their loved one to live the end with knowledge, consciousness, and humanity and hence without fear, anxiety and uncertainty. This protocol reflects the concept of true prevention in medicine that in no way excludes the sick person. It provides the opportunity of a multidimensional accompaniment in a natural and personalistic way (Tambone, 2003). Therefore, the NDP demands an adequate training of the caring team and the recognition of a shared path of care to ensure a standard of quality in the end of life, that is a time for which procedural transparency may be very relevant. In other words, our first proposal for a natural death protocol converges here with the need to promote a renewed research aimed at developing good evidence on which the opportune management of the dying process should be based.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.