With standardized screening tools, research studies have shown that developmental disabilities can be detected reliably and with validity in children as young as 4 months of age by using the instruments such as the Ages and Stages Questionnaire.

In this review, we will focus on one tool, the Ages and Stages Questionnaire, to illustrate the usefulness of developmental screening across the globe.

Mediante el uso de herramientas de evaluación estandarizada, algunos estudios de investigación han demostrado que discapacidades de desarrollo se pueden detectar con fiabilidad y validez en niños desde los 4 meses de edad mediante el uso de los instrumentos estandarizados como el Ages and Stages Questionnaire (Cuestionario de las Edades y Etapas).

Para ilustrar la utilidad de la evaluación del desarrollo infantil a escala global, en este trabajo se revisará la herramienta Ages and Stages Questionnaire.

Early childhood is a critical period because the first five years of life are fundamentally important, and early experiences provide the base for brain development and functioning throughout life.1,2 Early intervention services can provide educational and therapeutic services to children who are at risk.2,3 Early identification of developmental disabilities is essential for timely remedial intervention and leads to early treatment and ultimately improved long-term outcomes.4–6 It has been estimated that only about half of the children with developmental problems are detected before they begin school.7–9Early intervention for children with developmental delay is crucial for enhancing their outcomes.10,11 To meet the needs of children during the most important phase of their growth, many countries have established programs and facilities designed to mitigate disabilities.12 Early intervention (EI) and early childhood special education (ECSE) serve a growing number of young children with developmental delays and their families.13–17 It has been shown that high-quality EI and ECSE improve children's developmental outcomes.18–20

2Developmental screeningOptimal development and early identification and detection of delays rely on developmental screening.19,21 To emphasize the importance of developmental screening in early childhood, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) developmental screening policy has included the following strong statement: “Early identification of developmental disorders is critical to the well-being of children and their families.”22,23 Developmental screening can be thought of as a preliminary step in the identification of risk at school-age children.24 An effective screening tool should be inexpensive, simple, accurate, valid, reliable, culturally appropriate, easy, and quick to administer.25–27To be eligible for Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) services, children must qualify in terms of impairment or delay. Approximately 10 to 20% of young children will experience delays28–30 with significantly higher rates among children who live in poverty.31,32 It has been estimated that only about half of the children with developmental problems are detected before they join the school.33–35 Developmental screening and developmental surveillance constitute ongoing processes of monitoring the status of a child by gathering information about his development from multiple sources, including skillful direct observation from parents/caregivers and relevant professionals.26,36,37 The AAP and the British Joint Working Party on Child Health Services recommend developmental surveillance as an effective means to identify children with developmental delay.38 Parents’ reports of current attainment of developmental tasks have been shown to be accurate and reliable.39,40 In keeping with recommendations from the American Pediatric Association (USA), National Screening Committee (NSC) UK: Child Health Sub-Group Report 1999 and Best Health for Children (Ireland) consideration should be given to the use of parental reports as a part of the process of assessment.

The AAP41 policy statement set forth screening algorithms and methods, including those that use standardized parent-completed tools, such as the Parental Evaluation of Developmental Status (PEDS),39,40 the Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ),42 and the Child Development Inventories (CDI).43 These have the benefit of good psychometric properties (70-80% specificities and sensitivities), and require much less time than direct developmental assessment by a professional. A parent-completed screening questionnaire can decrease costs and increase accuracy, and parents can report successfully at regular intervals.19,44,45

Developmental screening identifies those who are in need of further evaluation for eligibility for specialized services.46–48 Eligibility assessment assists in identifying the nature of the delay and connecting children and families to appropriate services and supports. Several screening tests have been recommended for accurate ongoing developmental screening, including the PEDS, CDI, ASQ. The ASQ will be highlighted in the review as a preferred screening test that works well in a variety of screening settings.

3Ages and Stages QuestionnaireThe Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ) is a parent-completed questionnaire that may be used as a general developmental screening tool. The ASQ was designed and developed by J. Squires and D. Bricker42,49,50 at the University of Oregon and can be completed by parents in 12-18minutes. The ASQ-3 is a parent reported initial level developmental screening instrument consisting of 21 intervals, each with 30 items in five areas: (i) personal social, (ii) gross motor, (iii) fine motor, (iv) problem solving, and (v) communication for children from 2-66 months. In most cases, these questionnaires accurately identify young children who are in need of further evaluation to determine if they are eligible for early intervention services.42,50 The ASQ is cost-effective and widely used in the United States and other countries.51–53 The ASQ has been translated into several languages, such as Spanish, French, Dutch, Chinese, Norwegian, Hindi, Persian, and Turkish. Furthermore, the number of international studies on its psychometric properties with diverse cultural environments is increasing (e. g., Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Denmark, Ecuador, France, Ghana, India, Iran, Korea, Lebanon, Netherland, Norway, Republic of Macedonia, Spain, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey). It has excellent psychometric properties, test-retest reliability of 92%, sensitivity of 87.4% and specificity of 95.7%. Validity has been examined across different cultures and communities across the world.51–54 The ASQ-3 is designed to be an in-depth general screening instrument with a reading level from fourth to eighth grade and illustrations assist in providing a clear, user-friendly format. The ASQ is available in several languages, including Turkish, Norwegian, Dutch, Persian, Arabic, English, Hindi, French, Thai, Korean, Spanish, Chinese, and Vietnamese. Another advantage of the ASQ is its flexibility. Evidence has shown that the ASQ is very useful in a wide variety of settings: home, doctors’ office, head starts, early intervention units, preschools, early childhood, health clinics, and teen parenting programs. The ASQ can be completed by parents/caregivers independently or with the assistance of professionals or administered by a trained professional who is familiar with the child. Scores are normed to indicate whether children are developing in an age-appropriate manner.

Psychometric parameters of the ASQ have been examined based on completion of 18,000 respondents.42 Evidence shows that the ASQ is an accurate, cost-effective, parent-friendly instrument for screening and monitoring of preschool children. In addition, it is recommended for early detection of autism by the Joint Committee on Screening and Diagnosis of Autism as well as for general developmental follow-up and screening and developmental surveillance in office settings. Furthermore, research shows that the ASQ has been successfully used for follow-up and assessment of premature and at-risk infants and children in the public health,55,56 and follow-up of infants born after assisted reproductive technologies. The ASQ can also be used for teaching medical students in higher education and research about early intervention.57 In 2006, the ASQ was used for evaluating the developmental surveillance and screening algorithm by AAP (2001, 2006). Also, the ASQ was used to determine the prevalence of late language emergence and to investigate the predictive status of maternal, family, and child variables. Finally, the ASQ have been translated and used cross-culturally with success.51–54

4Comparison or agreement with other developmental instrumentsThe agreement between the ASQ and Developmental Assessment Scale for Indian Infants (DASII) was studied.58,59 The overall sensitivity of the ASQ in detecting delay was 83.3% (n=200) and specificity was 75.4% (n=200). All correlations were found to be acceptable (r 0.76-0.80). The sensitivity was higher in the high-risk group whereas specificity was higher in the low-risk group. There was a solid correlation between the domain scores of ASQ and DASII.42,58 Australian studies showed similar results while evaluating the ASQ in a medically at-risk for developmental delay population.60,61

The agreement between the ASQ and the Battelle Developmental Inventory, 2nd Edition (BDI-2) was also examined.62 The ASQ accurately identified and classified children as being eligible or those in need of further evaluation for eligibility status when the classification criterion was the BDI-2, with the ASQ accurately identifying over 90% of eligible children. Interobserver reliability was also strong, with most correlations over 0.70.63

The agreement between the ASQ and pediatrician estimates of development (i.e., Pediatric Developmental Impression (PDI)) was studied in 2007. Findings showed that the agreement between PDI and ASQ was 81.8%. The ASQ results indicated that 78.4% (n=548) were typically developed, while the PDI indicated that 89.4% (n=625) were typically developed.64

The agreement between the ASQ and the Bayley Scales of Infant Development II (BSID-II) was studied. The researchers calculated the sensitivity and specificity of the ASQ. They reported a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 87% for children of 24 months of age.65

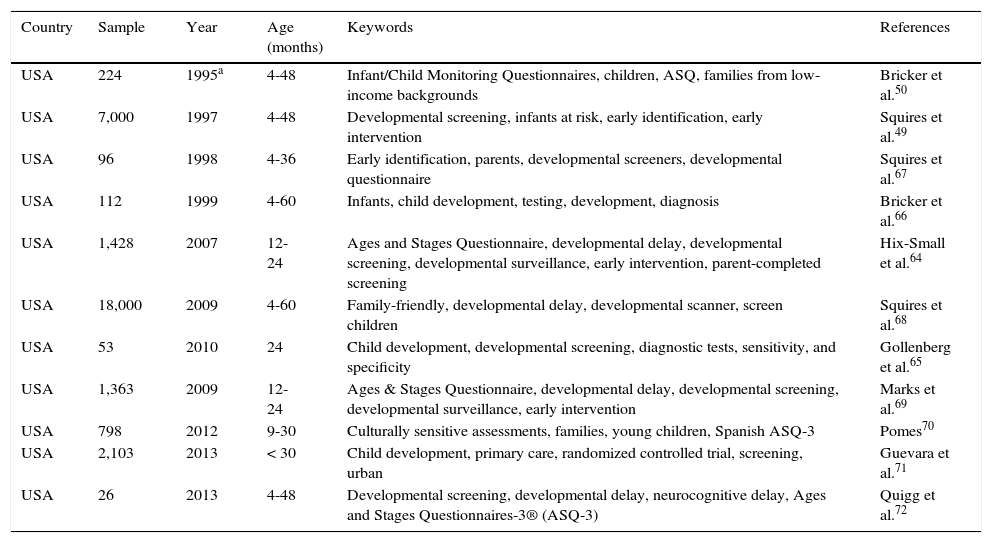

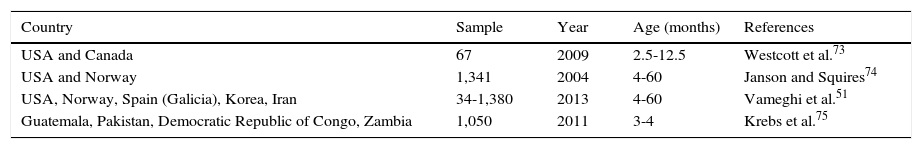

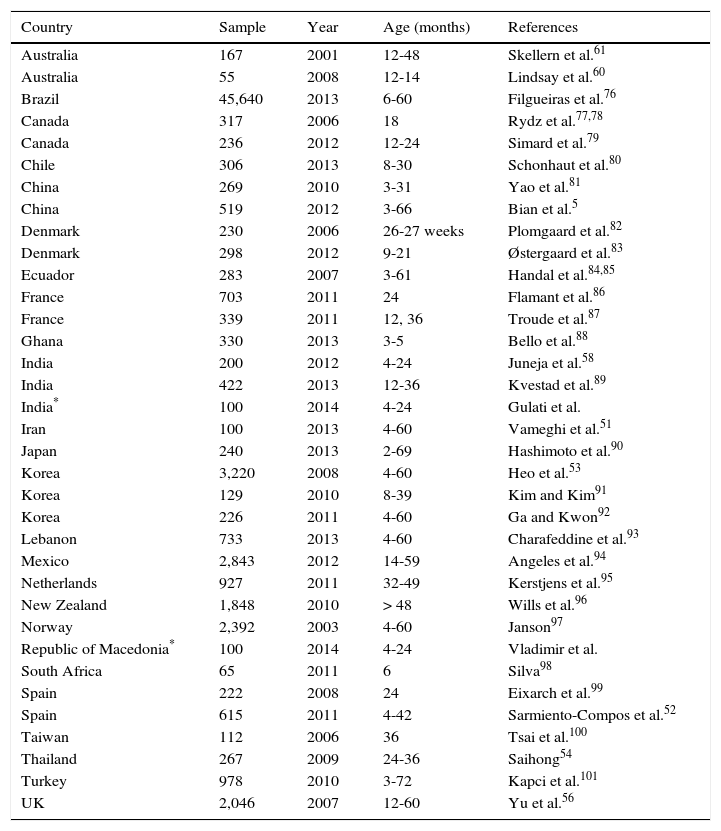

5ASQ study samplesThe ASQ has been used internationally in a variety of settings and contexts. The following tables summarize the overall results: research studies in the United Sates (Table 1);66–72 comparison of results from international research studies with those from the United States (Table 2);73–75 international research studies (Table 3);76–101 and some international research studies using the ASQ in different settings (Table 4).

ASQ studies in the United States, including original normative studies.

| Country | Sample | Year | Age (months) | Keywords | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 224 | 1995a | 4-48 | Infant/Child Monitoring Questionnaires, children, ASQ, families from low-income backgrounds | Bricker et al.50 |

| USA | 7,000 | 1997 | 4-48 | Developmental screening, infants at risk, early identification, early intervention | Squires et al.49 |

| USA | 96 | 1998 | 4-36 | Early identification, parents, developmental screeners, developmental questionnaire | Squires et al.67 |

| USA | 112 | 1999 | 4-60 | Infants, child development, testing, development, diagnosis | Bricker et al.66 |

| USA | 1,428 | 2007 | 12-24 | Ages and Stages Questionnaire, developmental delay, developmental screening, developmental surveillance, early intervention, parent-completed screening | Hix-Small et al.64 |

| USA | 18,000 | 2009 | 4-60 | Family-friendly, developmental delay, developmental scanner, screen children | Squires et al.68 |

| USA | 53 | 2010 | 24 | Child development, developmental screening, diagnostic tests, sensitivity, and specificity | Gollenberg et al.65 |

| USA | 1,363 | 2009 | 12-24 | Ages & Stages Questionnaire, developmental delay, developmental screening, developmental surveillance, early intervention | Marks et al.69 |

| USA | 798 | 2012 | 9-30 | Culturally sensitive assessments, families, young children, Spanish ASQ-3 | Pomes70 |

| USA | 2,103 | 2013 | < 30 | Child development, primary care, randomized controlled trial, screening, urban | Guevara et al.71 |

| USA | 26 | 2013 | 4-48 | Developmental screening, developmental delay, neurocognitive delay, Ages and Stages Questionnaires-3® (ASQ-3) | Quigg et al.72 |

ASQ International research results compared with those in the United States.

| Country | Sample | Year | Age (months) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA and Canada | 67 | 2009 | 2.5-12.5 | Westcott et al.73 |

| USA and Norway | 1,341 | 2004 | 4-60 | Janson and Squires74 |

| USA, Norway, Spain (Galicia), Korea, Iran | 34-1,380 | 2013 | 4-60 | Vameghi et al.51 |

| Guatemala, Pakistan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Zambia | 1,050 | 2011 | 3-4 | Krebs et al.75 |

International ASQ research studies.

| Country | Sample | Year | Age (months) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 167 | 2001 | 12-48 | Skellern et al.61 |

| Australia | 55 | 2008 | 12-14 | Lindsay et al.60 |

| Brazil | 45,640 | 2013 | 6-60 | Filgueiras et al.76 |

| Canada | 317 | 2006 | 18 | Rydz et al.77,78 |

| Canada | 236 | 2012 | 12-24 | Simard et al.79 |

| Chile | 306 | 2013 | 8-30 | Schonhaut et al.80 |

| China | 269 | 2010 | 3-31 | Yao et al.81 |

| China | 519 | 2012 | 3-66 | Bian et al.5 |

| Denmark | 230 | 2006 | 26-27 weeks | Plomgaard et al.82 |

| Denmark | 298 | 2012 | 9-21 | Østergaard et al.83 |

| Ecuador | 283 | 2007 | 3-61 | Handal et al.84,85 |

| France | 703 | 2011 | 24 | Flamant et al.86 |

| France | 339 | 2011 | 12, 36 | Troude et al.87 |

| Ghana | 330 | 2013 | 3-5 | Bello et al.88 |

| India | 200 | 2012 | 4-24 | Juneja et al.58 |

| India | 422 | 2013 | 12-36 | Kvestad et al.89 |

| India* | 100 | 2014 | 4-24 | Gulati et al. |

| Iran | 100 | 2013 | 4-60 | Vameghi et al.51 |

| Japan | 240 | 2013 | 2-69 | Hashimoto et al.90 |

| Korea | 3,220 | 2008 | 4-60 | Heo et al.53 |

| Korea | 129 | 2010 | 8-39 | Kim and Kim91 |

| Korea | 226 | 2011 | 4-60 | Ga and Kwon92 |

| Lebanon | 733 | 2013 | 4-60 | Charafeddine et al.93 |

| Mexico | 2,843 | 2012 | 14-59 | Angeles et al.94 |

| Netherlands | 927 | 2011 | 32-49 | Kerstjens et al.95 |

| New Zealand | 1,848 | 2010 | > 48 | Wills et al.96 |

| Norway | 2,392 | 2003 | 4-60 | Janson97 |

| Republic of Macedonia* | 100 | 2014 | 4-24 | Vladimir et al. |

| South Africa | 65 | 2011 | 6 | Silva98 |

| Spain | 222 | 2008 | 24 | Eixarch et al.99 |

| Spain | 615 | 2011 | 4-42 | Sarmiento-Compos et al.52 |

| Taiwan | 112 | 2006 | 36 | Tsai et al.100 |

| Thailand | 267 | 2009 | 24-36 | Saihong54 |

| Turkey | 978 | 2010 | 3-72 | Kapci et al.101 |

| UK | 2,046 | 2007 | 12-60 | Yu et al.56 |

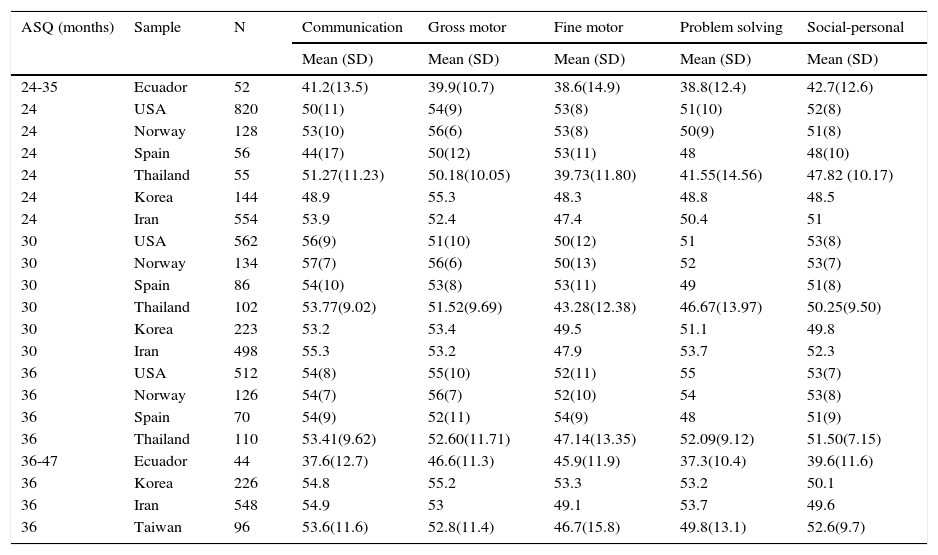

Comparative results of ASQ at different ages among samples from different countries.

| ASQ (months) | Sample | N | Communication | Gross motor | Fine motor | Problem solving | Social-personal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| 24-35 | Ecuador | 52 | 41.2(13.5) | 39.9(10.7) | 38.6(14.9) | 38.8(12.4) | 42.7(12.6) |

| 24 | USA | 820 | 50(11) | 54(9) | 53(8) | 51(10) | 52(8) |

| 24 | Norway | 128 | 53(10) | 56(6) | 53(8) | 50(9) | 51(8) |

| 24 | Spain | 56 | 44(17) | 50(12) | 53(11) | 48 | 48(10) |

| 24 | Thailand | 55 | 51.27(11.23) | 50.18(10.05) | 39.73(11.80) | 41.55(14.56) | 47.82 (10.17) |

| 24 | Korea | 144 | 48.9 | 55.3 | 48.3 | 48.8 | 48.5 |

| 24 | Iran | 554 | 53.9 | 52.4 | 47.4 | 50.4 | 51 |

| 30 | USA | 562 | 56(9) | 51(10) | 50(12) | 51 | 53(8) |

| 30 | Norway | 134 | 57(7) | 56(6) | 50(13) | 52 | 53(7) |

| 30 | Spain | 86 | 54(10) | 53(8) | 53(11) | 49 | 51(8) |

| 30 | Thailand | 102 | 53.77(9.02) | 51.52(9.69) | 43.28(12.38) | 46.67(13.97) | 50.25(9.50) |

| 30 | Korea | 223 | 53.2 | 53.4 | 49.5 | 51.1 | 49.8 |

| 30 | Iran | 498 | 55.3 | 53.2 | 47.9 | 53.7 | 52.3 |

| 36 | USA | 512 | 54(8) | 55(10) | 52(11) | 55 | 53(7) |

| 36 | Norway | 126 | 54(7) | 56(7) | 52(10) | 54 | 53(8) |

| 36 | Spain | 70 | 54(9) | 52(11) | 54(9) | 48 | 51(9) |

| 36 | Thailand | 110 | 53.41(9.62) | 52.60(11.71) | 47.14(13.35) | 52.09(9.12) | 51.50(7.15) |

| 36-47 | Ecuador | 44 | 37.6(12.7) | 46.6(11.3) | 45.9(11.9) | 37.3(10.4) | 39.6(11.6) |

| 36 | Korea | 226 | 54.8 | 55.2 | 53.3 | 53.2 | 50.1 |

| 36 | Iran | 548 | 54.9 | 53 | 49.1 | 53.7 | 49.6 |

| 36 | Taiwan | 96 | 53.6(11.6) | 52.8(11.4) | 46.7(15.8) | 49.8(13.1) | 52.6(9.7) |

Results from the ASQ studies in North America (USA), South America (Ecuador), Europe (Norway, Spain), and Asia (Korea, Taiwan) are summarized for selected groups of age. ASQ study results including children's mean scores and standard deviation are included for studies conducted in Ecuador, USA, Norway, Spain, Thailand, Korea, Taiwan, and Iran (Table 3).51–54,74,84,85,100

These samples followed a distribution pattern and very closely resembled the North American, South American, Asian, and European profiles. These results suggest that the ASQ performance did not diverge significantly from performance data collected in any other studies.

To demonstrate the usefulness of developmental screening across the globe, the authors of this paper have reviewed the ASQ as one example of a recommended tool that has a worldwide use for the goal of early detection and identifying developmental disabilities. It is important to promote early detection efforts using a valid and reliable global screening scale to control the healthy children population < 5 years of age. These studies reflect that the ASQ is very useful for early identification of the at-risk population and used to improve the early identification of young children and improve outcomes before disabilities become more established.12,26,27,102 Within only a few years, the ASQ has become widespread and increasingly used worldwide as a parent-completed questionnaire, a global screening scale. International studies yielded standardized parent-completed scores that were effective and comparative across languages and cultures. The ASQ has shown to be reliable and cost-effective as well as correlate well with pediatricians’ and service providers’ assessment.102 International interest has been building based on demonstrated benefits of the ASQ. Since some of the research studies reported here are ongoing, a number of additional international publications concerning the ASQ can be expected in the near future. Collaboration across the world will further enhance the utility of the ASQ because the establishment of norms from datasets with specified characteristics allows for cross-country comparisons of developmental outcomes in diverse cultures.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest of any nature.