La incidencia anual del síndrome nefrótico se ha estimado en 1-3 por cada 100,000 niños menores de 16 años de edad.

En niños, la causa más común del síndrome nefrótico es el síndrome nefrótico idiopático (SNI), que se define por la presencia de proteinuria e hipoalbuminemia y es, por definición, unaenfermedad primaria. En el estudio de la biopsia renal se pueden encontrar alteraciones histológicas renales no específicas que incluyen lesiones mínimas, glomeruloesclerosis segmentaria y focal y proliferación mesangial difusa.

En todos los pacientes con SNI se indica el tratamiento con corticosteroides, ya que, habitualmente, no se requiere de una biopsia renal antes de iniciar el tratamiento. La mayoría de los pacientes (80-90%) responden a este tratamiento. Los niños con SNI que no presentan remisión completa con el tratamiento con corticosteroides generalmente presentan glomeruloesclerosis segmentaria y focal, y requieren tratamiento con inhibidores de calcineurina (ciclosporina o tacrolimus), mofetil micofenolato o rituximab, además del bloqueo del sistemareninaangiotensina.

En este artículo se revisan las recomendaciones recientes aceptadas para el tratamiento de los niños con SNI.

The annual incidence of the nephrotic syndrome has been estimated to be 1-3 per 100,000 children < 16 years of age.

In children, the most common cause of nephrotic syndrome is idiopathic nephrotic syndrome (INS). INS is defined by the presence of proteinuria and hypoalbuminemia and by definition is a primary disease. Renal biopsy study shows non-specific histological abnormalities of the kidney including minimal changes, focal and segmental glomerular sclerosis, and diffuse mesangial proliferation.

Steroid therapy is applied in all cases of INS. Renal biopsy is usually not indicated before starting corticosteroid therapy. The majority of patients (80-90%) are steroid-responsive. Children with INS who do not achieve a complete remission with corticosteroid therapy commonly present focal and segmental glomerular sclerosis and require treatment with calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporin or tacrolimus), mycophenolate mofetil or rituximab, plus renin-angiotensin system blockade.

In this article we review the recent accepted recommendations for the treatment of children with INS.

1. Introduction

Nephrotic syndrome (NS) is a condition in which loss of proteins through the glomerular filter occurs. The resultant proteinuria is usually accompanied by edema, hypoproteinemia, hyperlipidemia, and other metabolic disorders. It has been estimated that the annual incidence of NS is 1-3/100,000 children<16 years of age. NS is classified as idiopathic when it is due to primary glomerulopathies or may be secondary to various disorders.1-3

Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome (INS) is the most common form of this condition in children. Most children with INS have minimal glomerular lesions on histological examination of the renal biopsy. Less frequently, the other two characteristic lesions of INS are observed: hypercellularity or diffuse mesangial proliferation and focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS). Approximately 80-90% of children with INS respond to treatment with corticosteroids2,3; therefore, it is classified as steroid-sensitive INS.

Normally, renal biopsy is not required to indicate initial steroid treatment in children with INS. In this regard, the International Study of Kidney Diseases in Children (ISKDC) demonstrated that up to 93% of children with INS and minimal glomerular lesions responded to the initial steroid treatment. On the other hand, 25-50% of children with histological kidney lesions of diffuse mesangial proliferation or FSGS also responded to the initial treatment.4 Patients who do not respond to treatment have been classified as steroid-resistant INS.5

2. Steroid-sensitive INS

It has been reported that the majority of patients with steroid-sensitive INS have minimal glomerular lesions. Nephrotic syndrome with minimal glomerular lesions is characterized by normal glomerular histological findings using optical microscopy, absence of deposits of immunocomplexes with immunofluorescence and extensive fusion of the pedicles on examination with electron microscopy.

2.1. Clinical manifestations

Up to one third of children with INS may have a history of upper respiratory tract infection or other factors that precede the development of a generalized edema. Mentioned infections are usually of viral etiology. There may be a history that includes allergic problems (sensitivity to pollen, cow’s milk, to dust or bee stings), medications (ampicillin, trimethadione, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), or some immunizations (diphtheria vaccine, pertussis and tetanus). These histories are considered to be factors that precipitate NS, although apparently there is no cause-effect relationship.1

The disease can manifest itself clinically by edema, which is initially palpebral and subsequently generalized. Generally it depends on the force of gravity because in the vertical position (standing) it is greater in the lower extremities and in the horizontal position (lying down) it is in the back, neck and face. When anasarca develops there is ascites and genital edema, and there may be uni- or bilateral pleural effusion.1

2.2. Laboratory findings

The presence of severe proteinuria characterizes the picture of NS. Usually proteinuria is positive (three or four crosses) in the general urinalysis,>1 g/l and 40 mg/m2/h when determined with a 12-h nocturnal urine collection. As a consequence of the massive proteinuria there is a reduction in serum albumin levels to<2.5 g/dl (25 g/l) and frequently <1 g/dl (10 g/l). In the immunoglobulin concentration tests (Ig) there is an important reduction of serum IgG with a lower decrease of IgA and increase of IgM.1

Regarding lipid metabolism, an increase is usually seen in serum cholesterol concentration (>250 mg/dl or 6.4 mmol/l) and triglycerides (values>95th percentile for patient age).

Hemoglobin and hematocrit levels may be normal or increased in hypovolemic patients. There is no change in the numbers and proportion of leukocytes, although the platelets can achieve levels>500,000/mm3. There is barely an elevation seen in serum creatinine levels or these are found to be mildly elevated as a consequence of intravascular volume contraction.

According to the urinalysis, in addition to proteinuria, there may be microscopic hematuria in up to a fifth of the cases. Unlike other glomerular diseases such as IgA nephropathy or Henoch-Schönlein purpura, microscopic hematuria is not persistent and ceases in the first weeks after treatment initiation.

2.3. Treatment

2.3.1. Corticosteroids

Treatment with corticosteroids is begun after the presence of infection has been ruled out or if the infections have been successfully treated. Currently, the following steroid treatment scheme is recommended1,3 in the Departament of Nephrology, Hospital Infantil de México Federico Gómez (HIMFG):

1) First, prednisone 60 mg/m2/day or 2 mg/kg/day once daily for 6 weeks (maximum 60 mg)

2) Next, prednisone 40 mg/m2/day or 1.5 mg/kg/day as a single dose every 48 h for 6 weeks (maximum 40 mg)

In recent recommendations by KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes), in the chapter “Steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome” it is mentioned that daily treatment can be administered for 4-6 weeks. It is also suggested to indicate treatment on alternate days for a period of 2-5 months, gradually reducing the dose.3 In this regard, various studies have shown that prolonging the initial treatment (i.e., the first time that the patient receives the steroid treatment) of INS in children for periods varying from 3 to 7 months significantly reduces the number of relapses per patient per year and the number of children with frequent relapses.1

Approximately one third of children with INS will present a single episode of nephrotic problems and after responding to steroid treatment will not present relapses after 18-24 months of the initial response and will likely remain in permanent remission.6 Approximately 10-20% of patients who respond to the initial steroid treatment will relapse several months after the first episode and will present permanent remission after an additional three to four relapses after responding to new steroid treatments. Finally, ∼50% of children will continue to experience relapses and will be classified as frequently relapsing or steroid dependent.

A patient is classified with frequently relapsing NS when there are two or more relapses within 6 months or four or more relapses in 1 year and as steroid dependent when two consecutive relapses occur during treatment with corticosteroids on alternate days or within 2 weeks after treatment cessation.1

The scheme for treating episodes of relapses is prednisone at doses of 60 mg/m2/day or 2 mg/kg/day (maximum 60 mg) in a single dose up to 3 days after the proteinuria is corrected, followed by 4 weeks of prednisone 40 mg/m2/day or 1.5 mg/kg/day (maximum 40 mg) as a single dose on alternate days.3,6,7

In patients with steroid-dependent INS or with frequent relapses, a scheme of corticosteroids has been suggested that consists of administration of prednisone at doses of 40-60 mg/m2/day until the proteinuria is corrected for 4 to 5 days. Subsequently, prednisone is indicated on alternate days and the dose is reduced to 15-20 mg/m2/day according to the prednisone level at which the prior relapse occurred. This treatment is continued for 12 to 18 months, trying to maintain the dosage of prednisone as low as possible to minimize adverse effects. With this scheme it has been observed that the growth rate of the children is apparently not affected.6 If the treatment on alternate days does not maintain remission of the NS, it has been suggested to administer the prednisone daily at the lowest possible dose to maintain the remission for at least 3 months.3

2.3.2. Cyclophosphamide and chlorambucil

Cyclophosphamide and chlorambucil have been used with good effect in children with INS who have frequent relapses or are steroid dependent and who developed serious side effects with prolonged steroid treatment. Treatment is recommended at a dose of 2 mg/kg/day of cyclophosphamide as a single dose for 8 to 12 weeks, with maximum cumulative dose of 168 mg/kg.3 Cyclophosphamide is begun after remission of proteinuria has been obtained with steroid treatment3; the latter being progressively terminated during the following days. Chlorambucil is indicated at a dose of 0.1-0.2 mg/kg/day for 8 weeks with a maximum cumulative dose of 11.2 mg/kg.3

Cyclophosphamide toxicity includes leukopenia, hemorrhagic cystitis and alopecia. However, long-term toxicity may be manifested by malignancies, pulmonary fibrosis, ovarian fibrosis and infertility,8 the latter having a higher risk in males. Therefore, cyclophosphamide treatment for children with frequent relapses or steroid-dependent INS is not recommended in the Department of Nephrology at the HIMFG. In this respect, it should be noted that recent guidelines continue to recommend treatment with cyclophosphamide or chlorambucil as a first-choice treatment in children with frequent relapses or steroid dependent and who require suspension of prolonged steroid treatment.3

2.3.3. Cyclosporin and tacrolimus

Different studies have shown that cyclosporin could reduce the incidence of relapses from 75-90% in patients with NS who are frequent relapsers or are steroid dependent.

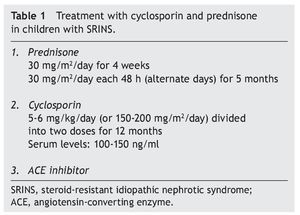

Recommended treatment includes the use of prednisone at 30 mg/m2/day for 4 weeks and subsequently the same dose on alternate days for 2 to 4 months. Treatment with cyclosporin is simultaneously initiated at a dose of 4-5 mg/ kg/day (150 mg/m2/day) divided into two doses. In the case of maintaining an adequate response after 4 to 6 months, a reduction in the dose of cyclosporin should be attempted to 3-4 mg/kg/day. Treatment is continued for 12 months when its suspension is indicated. It is recommended that serum levels of cyclosporin be maintained between 100 and 150 ng/ml.1

In patients in whom the cosmetic effects of cyclosporin are undesirable, tacrolimus can be used. A dose of 0.1 mg/ kg/day in divided doses every 12 h is indicated. Tacrolimus also has less nephrotoxicity.

In the latest review, KDIGO recommends that cyclosporin and tacrolimus be indicated for a period of at least 12 months due to the tendency for relapses when treatment is stopped.3

In children with INS who are frequent relapsers or who are steroid dependent, renal biopsy is recommended. In this manner, in addition to defining the type of glomerular lesion, the finding of significant tubular interstitial lesions could indicate not using treatment with calcineurin inhibitors and deciding on another treatment scheme.

2.3.4. Mycophenolate mofetil

The use of mycophenoate mofetil has been suggested in children with INS who are frequent relapsers and steroid dependent and require long-term treatment with cyclosporin and/or prednisone to maintain remission.9-11 The recommended dose is from 1,200 mg/m2/day in two doses each at 12 h for a period of at least 12 months. There also exists the tendency to present relapses when treatment is stopped,3 although a significant decrease in the number of relapses per year has been observed in some studies.12 Another available presentation for this drug, enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium in doses of 900 mg/m2/day, can also be used and is characterized by fewer gastrointestinal side effects. Because the dose of both presentations cannot be fractionated, it should be carefully adjusted to the body surface of the pediatric patient.

2.3.5. Rituximab

Rituximab is a murine-human monoclonal antibody directed against the CD20 antigen present in pre-B and B lymphocytes and has been mainly developed for the treatment of blood-related cancers. Favorable reports have been published of cases of patients with steroid-dependent INS who have attained a prolonged remission of proteinuria (>9 months) with rituximab treatment in conjunction with corticosteroids and tacrolimus.13 In the study by Ravani et al., treatment with rituximab allowed treatment with corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors to be suspended within 45 days after each rituximab infusion. In this study, after progressively reducing the dose of prednisone and the calcineurin inhibitor, rituximab at a dose of 375 mg/ m2 IV for an average of 6 h was recommended. The infusion was preceded by the administration of chlorpheniramine maleate, methyl prednisolone and paracetamol. In case of recurrence of the proteinuria, treatment with prednisone was indicated and 1 week later a second dose of rituximab. Patients included in this study received between 1 and 5 doses of rituximab.14 However, it has been commented that rituximab treatment does not cure NS, in addition to its effect being transitory in most patients.15

Furthermore, it has been observed that treatment with rituximab can be associated with the development of various side effects, some during the intravenous infusion of the drug (such as hypotension, fever, rash, diarrhea and bronchospasm). Also, patients can develop severe infections as a result of leukopenia and/or hypogammaglobulinemia.15-17 It has also been reported that a patient with NS died following the development of pulmonary fibrosis17 and another patient required heart transplantation due to severe myocarditis.18

2.3.6. Symptomatic and supportive treatment

During the period of nephrosis, it is advisable to restrict the addition of salt to foods.1 In patients with severe edema, especially with pulmonary ventilatory function compromise (due to anasarca and ascitis and pleural effusions), albumin infusion (20%) at a dose of 1 g/kg for 4 h and administration of furosemide IV at a dose of 1 to 2 mg/kg at initiation and completion of the albumin infusion is required. The patient should be monitored for the possible development of accentuated hypokalemia with this treatment.1

2.4. Progress and prognosis

Rüth et al. carried out a long-term evaluation of 42 children (26 males) with steroid-sensitive NS in childhood. They were followed for an average of 22 years after the initial diagnosis.8 Patients evaluated had an average age of 28 years (18-47 years). It was noted that 14 patients (33%) had recurrences of NS in adulthood and at the time of their follow-up visit five were receiving treatment (three with cyclosporin, one with prednisone on alternate days and one with ACE inhibitor). The factors that were identified as predictors of new relapses in adulthood included greater number of relapses during childhood and adolescence and a complicated course (frequent relapses or steroid dependence) that required administration of medications such as cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil and cyclosporin. The final height, body mass index and renal function were found to be within normal limits in all patients and globally the general mortality was low. Of the 24 patients who received treatment with cyclophosphamide, only two had children, compared with 6/18 patients who did not receive cyclophosphamide. It was also observed that patients with a history of two or more cycles of cyclophosphamide had a greater risk of not having children than those who received only one cycle of cyclophosphamide.8

3. Steroid-resistant INS

It is recommended for the pediatric patient to receive initial treatment with corticosteroids for a period of 8 weeks to define the presence of steroid resistance.3 In children who do not respond to treatment a percutaneous renal biopsy is indicated to diagnose the type of underlying renal histological lesion. In patients with steroid-resistant INS, the finding of FSGS on histological study of the renal biopsy is common. FSGS is a glomerular lesion that can also present in patients with renal disorders other than INS.1

Patients with INS may present the FSGS lesion as part of a syndrome or limited to the kidney (nonsyndromic). Genetic mutations of the nonsyndromic forms include genes that codify proteins of the cytoskeleton based on actin or on the midline diaphragm. Mutations of the NPHS2 gene that codify the production of podocin are most commonly found in INS with genetic FSGS. Mode of inheritance is autosomal recessive. The gene is located on chromosome 1q25-31. Mutations of the ACTN4 gene that codify alpha-actinin-4 have been observed in patients with INS with familial FSGS. In other patients, mutations in the CD2AP gene have been observed, which codifies the CD2-associated proteins.1 A distinctive feature is that these patients usually do not respond to steroid treatment or other immunosuppressive medications.19

3.1. Clinical and laboratory manifestations

Some studies have found that children with INS and histological renal lesions of FSGS are older than those who do not have this lesion.1 In children, the clinical picture is similar to what is seen in patients with INS of minimal glomerular lesions. Occasionally, a moderate grade of arterial hypertension is seen with greater frequency (15-20% of cases)20 and of microscopic hematuria (from 40-50% at the time of the initial presentation).20,21 However, because these clinical manifestations are also found in children with INS with minimal glomerular lesions they do not support the differential diagnosis between both clinical pictures.

3.2. Treatment

Treatment of patients with steroid-resistant INS (usually with histological renal lesions of FSGS) incorporates the aspects of conservative management and diverse therapeutic schemes directed at controlling proteinuria and preservation of renal function.22,23 Long-term follow-up studies in adults as well as children have demonstrated that preservation of renal function is directly associated with the degree of control of proteinuria.24-26

3.2.1. Corticosteroids

ISKDC studies showed that ∼30% of children with INS and FSGS had a response to the initial steroid treatment.7 However, a large proportion of relapses are seen in the months following initial treatment. In other cases, after an initial favorable response and other remissions in subsequent relapses, some patients have a lack of response to a new treatment and therefore is referred to as late steroid resistance.27,28 A lower treatment response to corticosteroids has been described in patients with mutations of the NPHS2 gene that codifies podocin of the podocytes.29

In patients with INS with FSGS and who respond to initial steroid treatment, it has been observed that 50% could remain in complete remission, 25% have subsequent partial remission and another 25% progress to late steroid resistance. Complete remission in these cases predicts a favorable long-term evolution, almost comparable to what has been observed in patients with INS with minimal glomerular lesions.1

In steroid-resistant patients, corticosteroids remain an important component in the various proposed alternative schemes and are usually given in combination with antiproliferative drugs or calcineurin inhibitors.

3.2.2. Cyclosporin

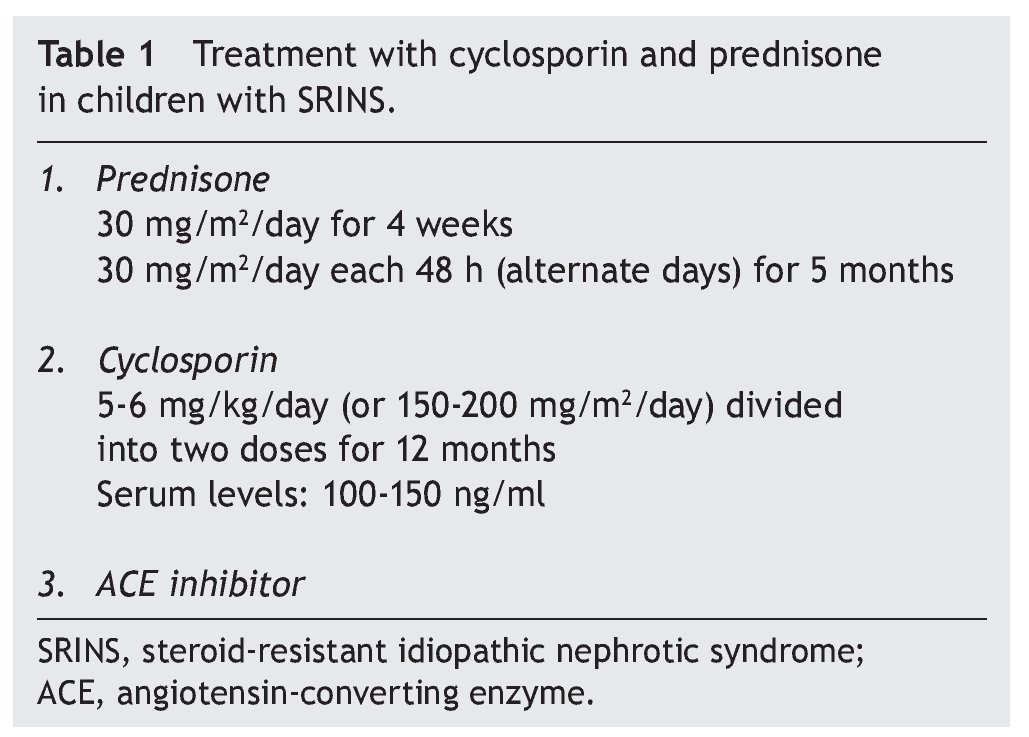

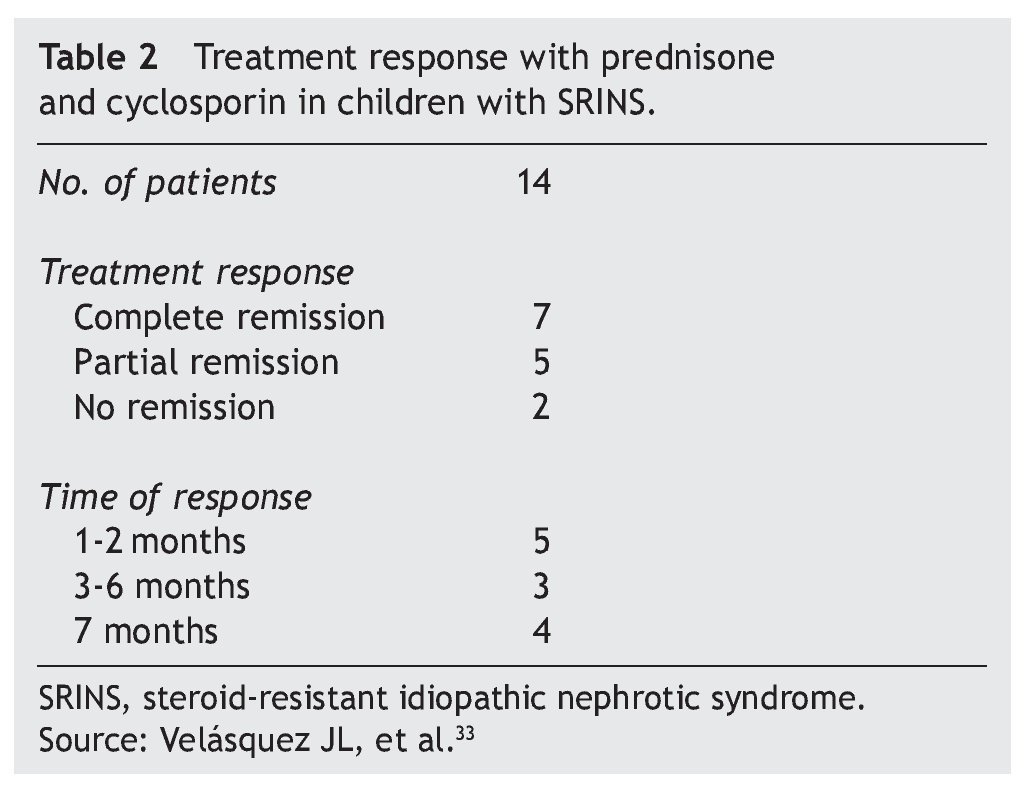

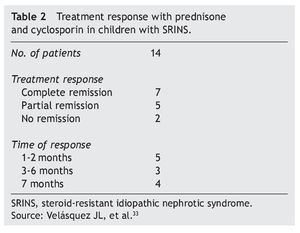

In studies performed in both children and adults, it has been shown that treatment with cyclosporin in association with prednisone has a greater efficacy in inducing remission than cyclosporin alone.30-32 The scheme used in the Department of Nephrology (HIMFG) is based on recommendations from Niaudet and Boyer6 and the KDIGO guidelines3 (Table 1). In a prior study conducted at the HIMFG Department of Nephrology,33 treatment was indicated with cyclosporin and prednisone for 14 children with steroid-resistant INS aged between 6 months and 6 years. In 13 patients, renal biopsy showed FSGS. In this study, seven patients had complete remission of NS; of these, two maintained remission for 3-4 years after stopping treatment with cyclosporine. One patient relapsed at 2 years but recovered with a new treatment; the other four patients maintained remission with the prolongation of treatment with cyclosporin (Table 2).33

In patients who had relapse of NS after discontinuation of treatment with cyclosporin (or other immunosuppressants) after having obtained complete remission, it is recommended to re-initiate steroid treatment or to repeat the prior treatment that induced remission or indicate an alternative immunosuppressive agent to minimize potential cumulative toxicity.3

Development of various adverse effects to treatment with anticalcineurics in children with steroid-resistant INS has been described. The frequency has ranged from 23% for developing high blood pressure to 17% for decrease in bone mineral density, with a frequency<6% of hypertricosis, cataracts and gingival hypertrophy.32 However, the most important side effect is that of the potential nephrotoxicity (vascular lesions, tubular atrophy and renal interstitial fibrosis), which is mainly seen after prolonged treatment (>24 months). Under these circumstances, as has already been mentioned, an alternative treatment scheme should be sought.

3.2.3. Tacrolimus

Diverse studies have been published on the usefulness of tacrolimus in children with steroid-resistant INS.34,35 The treatment scheme is similar to what is described with cyclosporin, i.e., in association with prednisone for a period of 6 months and an initial dose of tacrolimus of 0.1 mg/kg/ day divided into two doses with control of the tacrolimus levels and maintenance of blood levels between 5 and 10 ng/ ml. Treatment with tacrolimus is prolonged up to 12 months.

3.2.4. Alkylating agents

Cyclophosphamide and chlorambucil have been used in the treatment of patients with steroid resistant INS since the 1960s. Similarly, nitrogen mustard has been used.36 As previously described, the main indication for cytotoxic agents is for the treatment of patients with frequent relapses or those who are steroid dependent. However, although reports continue to be published about the probable favorable effect of the treatment with cyclophosphamide in patients with steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome,37 treatment effectiveness with cyclophosphamide at a dose of 2 mg/kg/day for 90 days was not demonstrated in a controlled study published by the ISKDC.38 Treatment with boluses of cyclophosphamide IV (monthly doses of 500 mg/m2 for 6-9 months) also did not have a favorable effect on inducing remissions in patients with steroid-resistant INS.39,40 Therefore, currently its use is not recommended in children with steroid-resistant INS.3

3.2.5. Mycophenolate mofetil

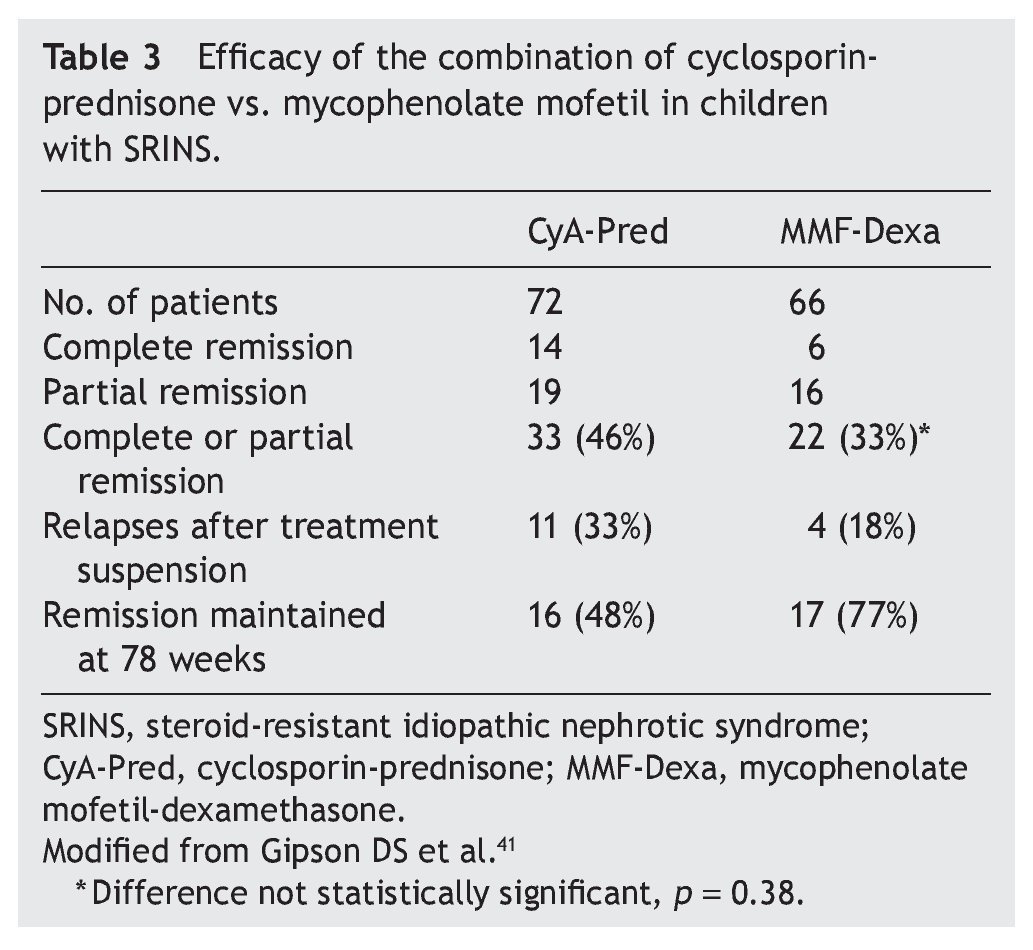

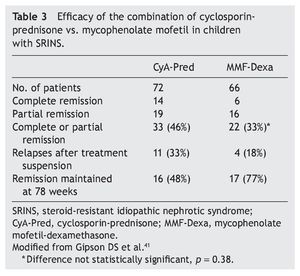

Mycophenolate mofetil (MM), an anti-proliferative agent, was introduced in the 1990s as an immunosuppressive agent in renal transplantation. The most important study with respect to the treatment with MM in patients with steroid-resistant NS was carried out by Gipson et al.41 In the study, 72 patients were included in the control group who received treatment with cyclosporin (5-6 mg/kg/ day, maximum 250 mg/day) in two doses for 1 year, maintaining blood levels between 100 and 250 ng/ml. The experimental patient group (66 patients) received MM at a dose of 25-36 mg/kg/day (maximum 2 g/day) for 1 year and dexamethasone (0.9 mg/kg/dose) 2 days/week for a total of 46 doses. In both groups, prednisone was indicated at a dose of 0.3 mg/kg/dose (maximum 15 mg) each 48 h for 6 months (Table 3). It is noted that although children from the experimental group had less frequency of complete or partial remission (the difference did not reach statistical significance, p = 0.38), they had less frequency of relapses and maintained a greater proportion in remission at 78 weeks of follow-up.41 Based on these results, treatment with MM is recommended and high doses of corticosteroids in children with steroid-resistant NS who have not had complete or partial remission with treatment with calcineurin inhibitors and corticosteroids.3

3.2.6. Rituximab

Gulati et al. reported the results of a study of 33 patients aged between 2 and 41 years (average 12.7 years) whose renal biopsy demonstrated minimal glomerular lesions (17 patients) and FSGS (16 patients).42 These patients presented steroid-resistant NS without response to other treatments with calcineurin inhibitors, MM, cyclophosphamide and other immunosuppressive agents. Treatment with rituximab was indicated at a dose of 375 mg/m2 each week for 4 weeks plus prednisone for 10 weeks. Complete or partial remission of NS was observed in 11 patients with minimal glomerular lesions (64%) and in five patients (30%) with FSGS. After an average follow-up of 21 months, 15 patients from both groups maintained complete (seven patients) or partial (eight patients) remission.42 However, to date, KDIGO3 guidelines do not recommend the use of rituximab in children with steroid-resistant NS until results of controlled studies are available43,44 and also due to the high risk of complications associated with its use.16-18

3.2.7. Conservative treatment

Management of electrolyte alterations and severe edema is similar to what is indicated for patients with INS and minimal glomerular lesions. However, in children with FSGS, because of the high frequency of lack of complete response to the treatments instituted and the persistence of proteinuria, control of hyperlipidemia and reduction of proteinuria with the use of ACE inhibitors is recommended.3,22,45 Use of enalapril has been recommended in these cases at a dose of 0.2 up to 0.6 mg/kg/day with dose-dependent response. However, one must carefully scrutinize for potential side effects that include reduction of glomerular filtration velocity and hemoglobin, hyperkalemia and clinically the development of angioedema and persistent cough.22

3.3. Evolution and prognosis

Evolution of children with steroid-resistant INS, the majority with FSGS lesions, depends on their response to the treatment instituted. Patients who are maintained in proteinuria remission usually progress in a favorable manner with preservation of renal function.25

In a series of 92 children with FSGS (seven with asymptomatic proteinuria without NS) followed on average for 8 years, Paik et al. observed a complete remission in 36 children (39%), partial remission in 14 (15%) and persistent NS in 13 (14%); nine patients (10%) had renal insufficiency and 20 had chronic end-stage renal insufficiency (21%). The average time from initial presentation to development of chronic end-stage renal disease was 67 ± 43 months and renal survival at 5, 10 and 15 years was 84, 64 and 53%, respectively.21

Finally, it should be mentioned that ∼30% of patients with NS and FSGS lesion will have recurrence of the disease after renal transplant is performed.46

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest of any nature.

Received 14 April 2014;

accepted 10 July 2014

E-mail:velasquezjones@hotmail.com