Thirty-six isolates of psittacid herpesvirus (PsHV), obtained from 12 different species of psittacids in Brazil, were genotypically characterized by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis and PCR amplification. RFLP analysis with the PstI enzyme revealed four distinct restriction patterns (A1, X, W and Y), of which only A1 (corresponding to PsHV-1) had previously been described. To study PCR amplification patterns, six pairs of primers were used. Using this method, six variants were identified, of which, variants 10, 8, and 9 (in this order) were most prevalent, followed by variants 1, 4, and 5. It was not possible to correlate the PCR and RFLP patterns. Twenty-nine of the 36 isolates were shown to contain a 419bp fragment of the UL16 gene, displaying high similarity to the PsHV-1 sequences available in GenBank. Comparison of the results with the literature data suggests that the 36 Brazilian isolates from this study belong to genotype 1 and serotype 1.

Pacheco's disease was first identified in Brazil in 1930 and described as causing acute hepatitis and death of birds from the Psittacidae family.1 In 1975, the etiologic agent for this disease was identified to be psittacid herpesvirus (PsHV).2 Since then, PsHV has been related to the death of psittacids in various parts of the world.3–6 However, few studies have been conducted in Brazil following the initial discovery and description of the disease.

PsHVs have been classified as members of the genus Iltovirus (α4) within the subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae, with the scientific name Psittacid herpesvirus 1.7 The viral genome consists of 163,025 base pairs (bp) (GenBank accession no. AY372243), contains 73 open reading frames (ORFs) and has a guanine and cytosine content of 60.95%.8

PsHVs have been classified into four genotypes, with distinct biological characteristics. They are thought to be latent in their host species; however, parrots infected with PsHV of a genotype to which they are not adapted have been discovered to contract an acute fatal disease.9

Several classification strategies have been proposed for PsHVs, based on their genetic and antigenic differences. Antigenic studies using cross-neutralization tests identified three serotypes of PsHVs and suggested the existence of two others.10 However, when genotypic differences are considered, viral polymorphisms are more evident, as demonstrated by a study based on PCR amplification patterns, where 10 different variants of PsHVs were identified.11 Another technique that has been used is restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis, which was able to identify up to 14 different patterns when the PstI restriction enzyme was used to digest the viral genome.12,13

The objective of this study was to characterize 36 isolates of PsHV-1, previously obtained from captive parrots from Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil,14 by PCR amplification and RFLP analysis using the PstI enzyme.

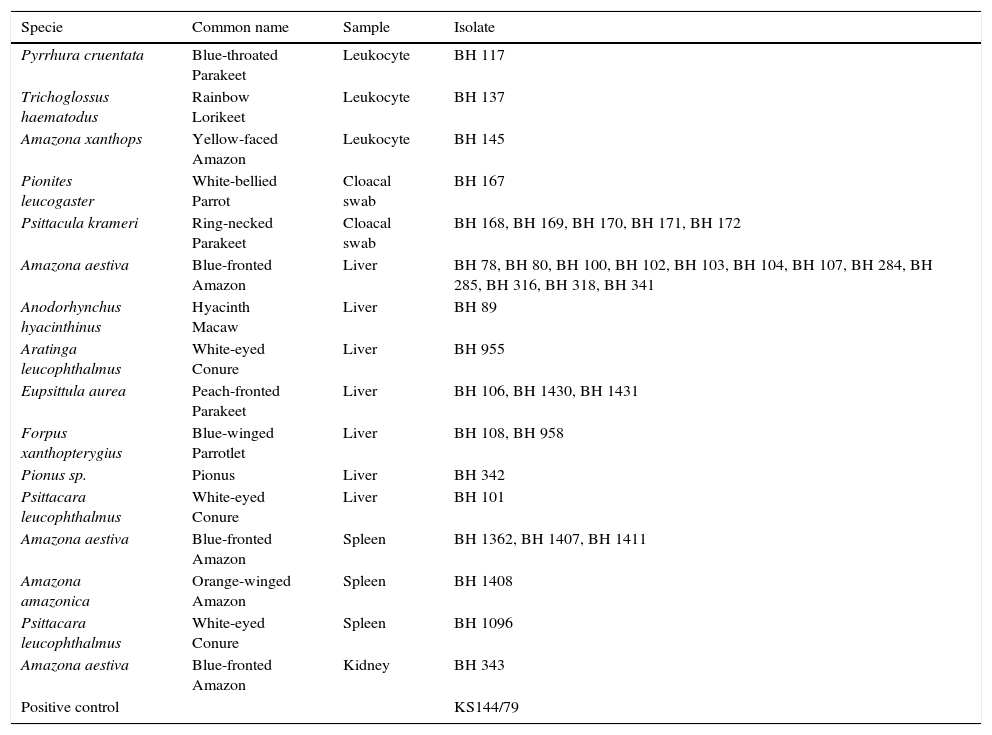

Materials and methodsVirus isolatesThe PsHV isolates used in this study (Table 1) were obtained from chicken embryo fibroblasts (CEF) inoculated with spleen, liver, or kidney tissue fragments, cloacal swabs, or leukocytes isolated from 36 psittacine birds. The birds belonging to 12 different species were held in captivity in institutions located in the city of Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.14 The original samples were collected prior to this study over a course of eight months, between September 2007 and April 2008.

List of isolates and their respective sources of isolation.

| Specie | Common name | Sample | Isolate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrrhura cruentata | Blue-throated Parakeet | Leukocyte | BH 117 |

| Trichoglossus haematodus | Rainbow Lorikeet | Leukocyte | BH 137 |

| Amazona xanthops | Yellow-faced Amazon | Leukocyte | BH 145 |

| Pionites leucogaster | White-bellied Parrot | Cloacal swab | BH 167 |

| Psittacula krameri | Ring-necked Parakeet | Cloacal swab | BH 168, BH 169, BH 170, BH 171, BH 172 |

| Amazona aestiva | Blue-fronted Amazon | Liver | BH 78, BH 80, BH 100, BH 102, BH 103, BH 104, BH 107, BH 284, BH 285, BH 316, BH 318, BH 341 |

| Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus | Hyacinth Macaw | Liver | BH 89 |

| Aratinga leucophthalmus | White-eyed Conure | Liver | BH 955 |

| Eupsittula aurea | Peach-fronted Parakeet | Liver | BH 106, BH 1430, BH 1431 |

| Forpus xanthopterygius | Blue-winged Parrotlet | Liver | BH 108, BH 958 |

| Pionus sp. | Pionus | Liver | BH 342 |

| Psittacara leucophthalmus | White-eyed Conure | Liver | BH 101 |

| Amazona aestiva | Blue-fronted Amazon | Spleen | BH 1362, BH 1407, BH 1411 |

| Amazona amazonica | Orange-winged Amazon | Spleen | BH 1408 |

| Psittacara leucophthalmus | White-eyed Conure | Spleen | BH 1096 |

| Amazona aestiva | Blue-fronted Amazon | Kidney | BH 343 |

| Positive control | KS144/79 |

The leukocytes and cloacal swab samples were collected from nine live birds, which displayed no clinical signs of disease at the time of sampling. The kidney, spleen and liver samples were collected from dead birds, of which, 26 had shown anorexia, apathy, and sudden death (no antemortem individual information was available) and one (BH 89), which had been examined before death, showed no clinical changes, but presented sudden death.

A reference virus (KS 144/79) was kindly provided by Prof. Dr. Erhard F. Kaleta from Klinik für Vögel, Reptilien, Amphibien und Fische, Justus-Liebig-Universität, Gieβen.

Cell culture and virus productionPrimary CEF (chicken embryo fibroblast) monolayers were prepared as described previously15 and grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 2mM l-glutamine (Gibco, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NE, USA) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Each isolate was inoculated into a culture flask containing a confluent CEF monolayer. Following observation of a cytopathic effect, the cells and medium were harvested. Viral precipitation was carried out with saturated ammonium sulfate solution, as described previously.16

Extraction of viral DNATotal DNA was extracted using a proteinase K/phenol–chloroform–isoamyl alcohol protocol as described previously.17

The purified DNA was eluted with water and stored at 4°C for at least 24h before use. The total DNA was analyzed and quantified using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer at 260–280nm (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

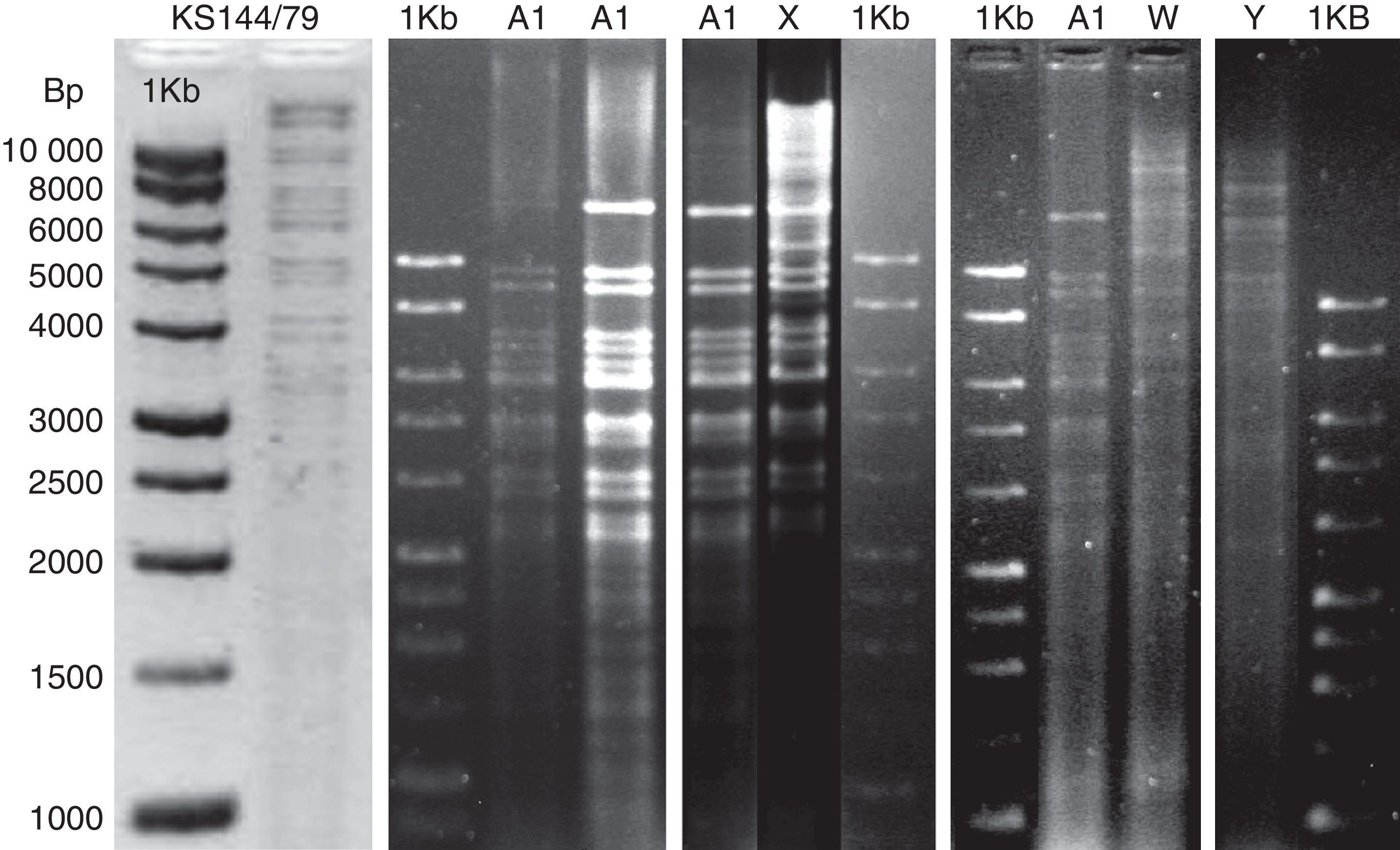

RFLP analysisThe DNA samples extracted from the PsHV isolates and from the reference virus (KS 144/79) were analyzed by RFLP for genotypic classification using the restriction enzyme PstI (20,000U/mL, New England BioLabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA), as recommended by the manufacturer.

The resulting DNA fragments were separated by electrophoresis on a 0.5% agarose gel in 1× Tris–acetate–EDTA buffer (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) containing 5μL of ethidium bromide (10mg/mL) (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NE, USA) at room temperature under constant voltage of 20V for about 15h. The BenchTop 1kb DNA Ladder (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was used as a DNA size marker. The gels were observed at 254nm using a MacroVue UV transilluminator (GE Healthcare, Cleveland, OH, USA) and photographed.

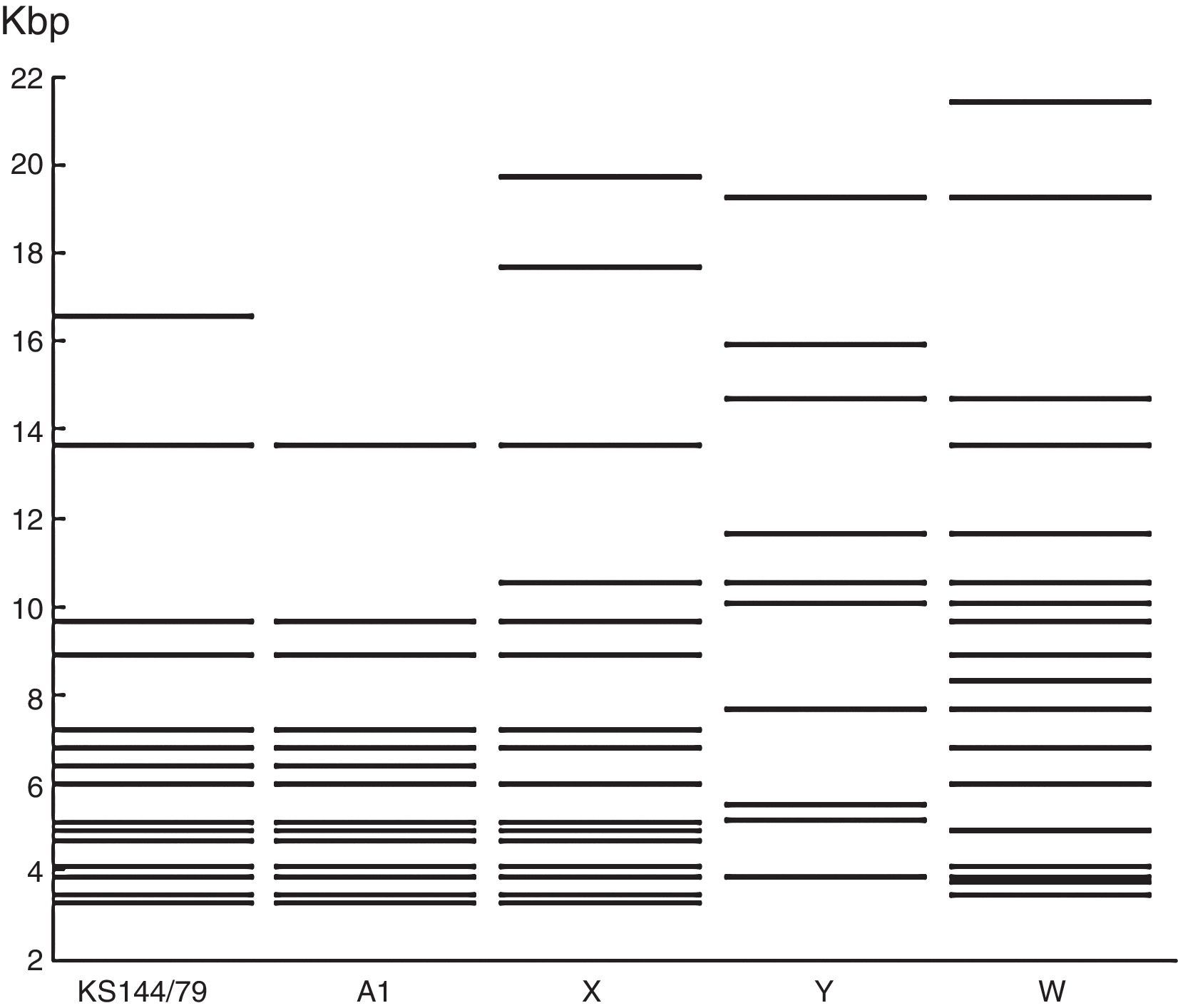

Restriction profile analysisThe fragments were visually identified on the gel photographs. Based on the DNA marker, an approximate molecular size of each fragment was calculated. Thus, it was possible to prepare a visual graphic picture of the restriction patterns obtained.

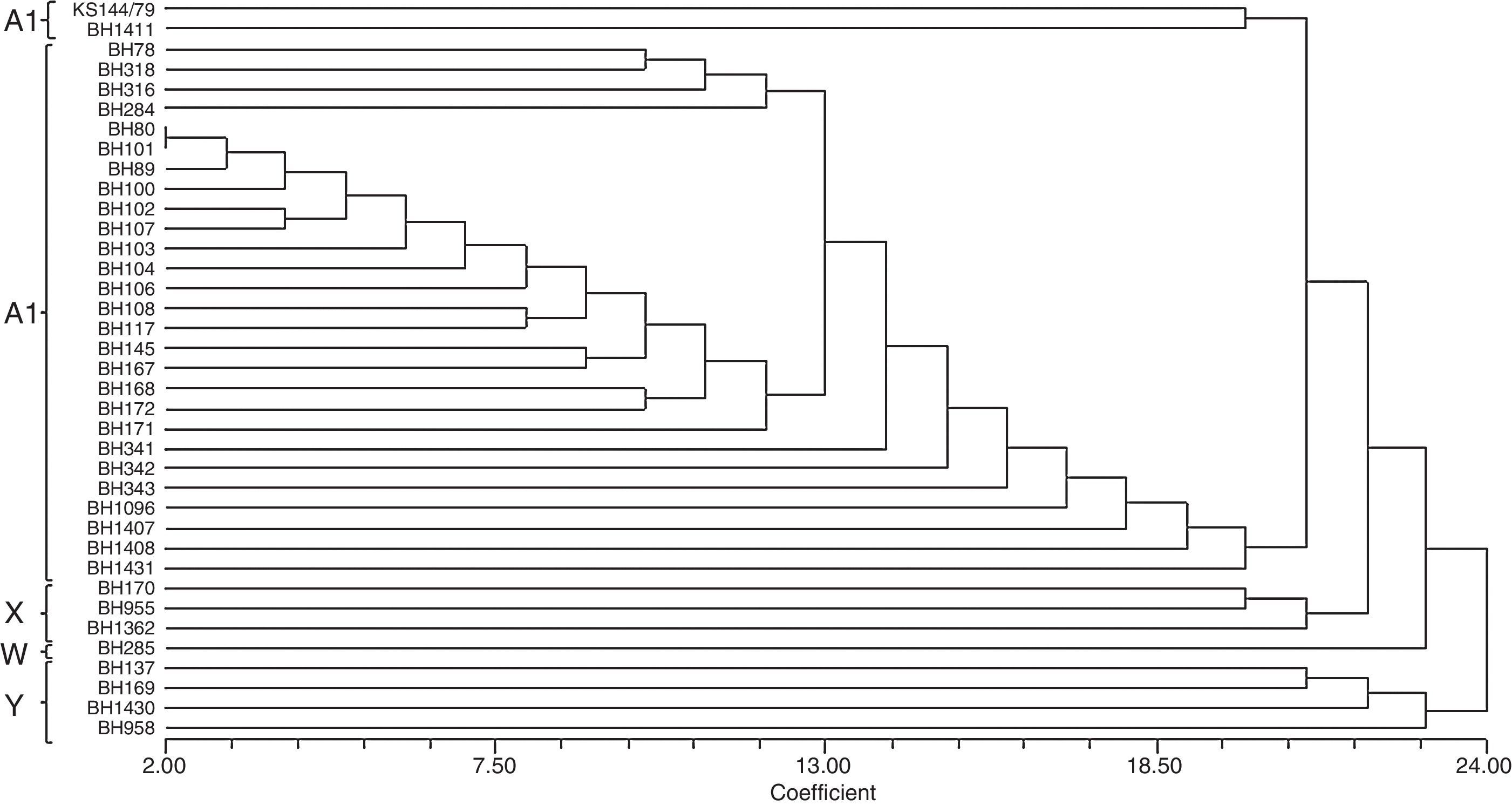

To prepare a dendrogram, the RFLP patterns were converted to binary matrices by assigning “1” for presence and “0” for absence of each fragment generated. Cluster analysis based on similarity was performed by the neighbor-joining method18 using the Sorensen-Dice coefficient with the program NTSYS-pc (Exeter Software, Setauket, NY, USA),19 as described in previous research studies.

PCR amplification patternsA 200μL aliquot of a cell culture suspension was used for DNA extraction using sodium iodide and silica according to the method described by Boom et al.20 The extracted total DNA was analyzed and quantified by measuring absorbance at 260nm on a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer.

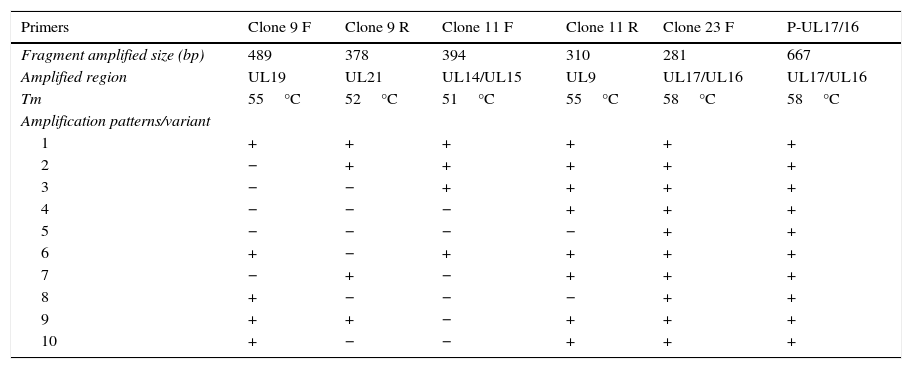

Each sample was amplified using six different pairs of primers described in the literature9,11 and capable of producing up to 10 different patterns by standard amplification (Table 2). The PCR reaction conditions were as described by Tomaszewski et al.,9,11 with modified annealing temperatures (Tm) for each pair of primers (optimized by gradient PCR), as specified in Table 2.

The used primers with respective Tm and possible amplification patterns as reported earlier.

| Primers | Clone 9 F | Clone 9 R | Clone 11 F | Clone 11 R | Clone 23 F | P-UL17/16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fragment amplified size (bp) | 489 | 378 | 394 | 310 | 281 | 667 |

| Amplified region | UL19 | UL21 | UL14/UL15 | UL9 | UL17/UL16 | UL17/UL16 |

| Tm | 55°C | 52°C | 51°C | 55°C | 58°C | 58°C |

| Amplification patterns/variant | ||||||

| 1 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2 | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| 3 | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| 4 | − | − | − | + | + | + |

| 5 | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| 6 | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| 7 | − | + | − | + | + | + |

| 8 | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| 9 | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| 10 | + | − | − | + | + | + |

In all PCR assays, reagent mixture without a template was used as a negative control, and DNA from isolate KS 144/79 (PsHV-1) was used as a positive control.

The PCR products were separated on a 1% agarose gel in Tris–Borate–EDTA buffer (TBE: 100mM Tris-base, pH 8.3, 25mM EDTA, 50mM boric acid) (Thermo Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) at room temperature under constant voltage of 100V and visualized using a UV transilluminator (GE Healthcare, Cleveland, OH, USA). A 100bp DNA Ladder (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used as DNA size marker.

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysisTwenty-nine of the isolates analyzed in this study carried a previously sequenced fragment of 419bp, coding for the UL16 ORF. These already known sequences were used to analyze the RFLP and PCR results.

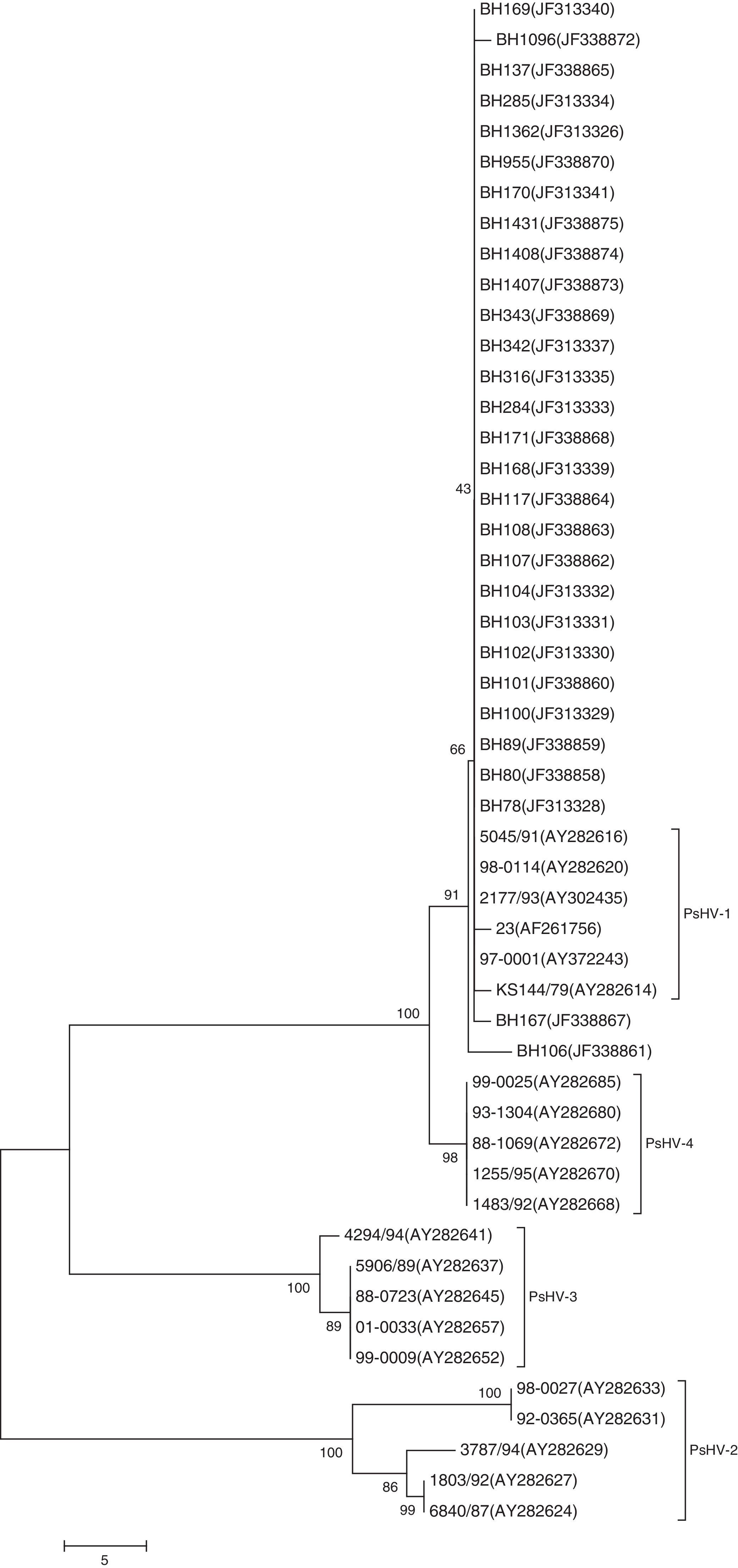

A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed by aligning the nucleotide sequences of the UL16 ORF of the Brazilian PsHV isolates and the sequences of PsHV-1, PsHV-2, PsHV-3 and PsHV-4 obtained from the NCBI sequence database. One thousand bootstrap replicates were used to assess the significance of the tree topology.

HistopathologyIn order to determine the cause of death and PsHV infection-related injuries, histopathological examination was performed on samples from 26 of the 27 dead birds. These results have been published previously.14

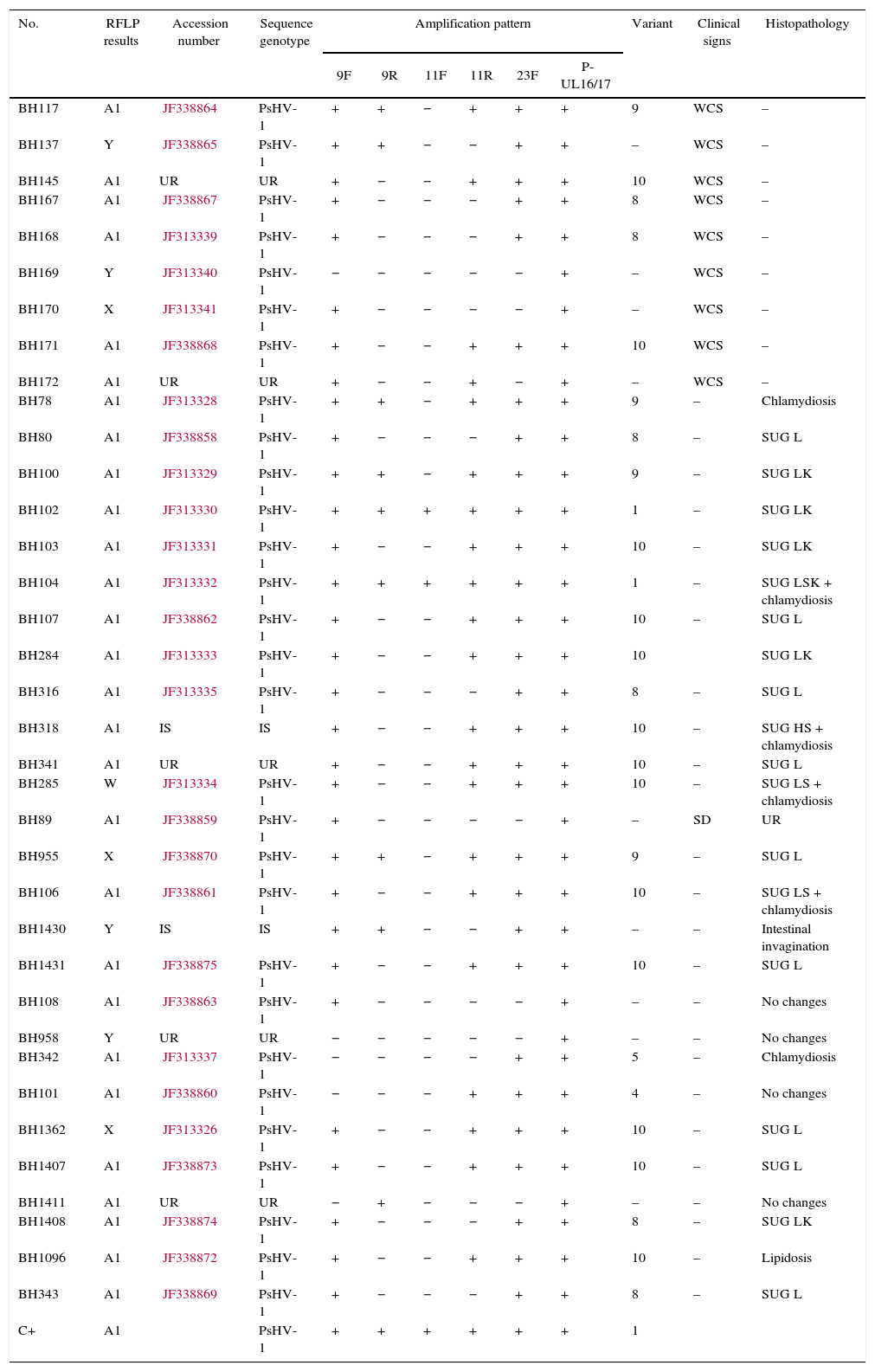

ResultsRestriction fragment length polymorphismThe PstI digestion of genomic DNA from the 36 isolates of PsHV revealed five different restriction patterns (Figs. 1 and 2). By comparing the restriction profiles obtained in this study, including the reference isolate (KS 144/79), with those described by Schröder-Gravendyck et al.,13 we were able to conclude that 28 isolates belonged to group A1 (Table 3).

Results of RFLP and PCR amplification patterns compared by sequences genotype.

| No. | RFLP results | Accession number | Sequence genotype | Amplification pattern | Variant | Clinical signs | Histopathology | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9F | 9R | 11F | 11R | 23F | P-UL16/17 | |||||||

| BH117 | A1 | JF338864 | PsHV-1 | + | + | − | + | + | + | 9 | WCS | – |

| BH137 | Y | JF338865 | PsHV-1 | + | + | − | − | + | + | – | WCS | – |

| BH145 | A1 | UR | UR | + | − | − | + | + | + | 10 | WCS | – |

| BH167 | A1 | JF338867 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | − | + | + | 8 | WCS | – |

| BH168 | A1 | JF313339 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | − | + | + | 8 | WCS | – |

| BH169 | Y | JF313340 | PsHV-1 | − | − | − | − | − | + | – | WCS | – |

| BH170 | X | JF313341 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | − | − | + | – | WCS | – |

| BH171 | A1 | JF338868 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | + | + | + | 10 | WCS | – |

| BH172 | A1 | UR | UR | + | − | − | + | − | + | – | WCS | – |

| BH78 | A1 | JF313328 | PsHV-1 | + | + | − | + | + | + | 9 | – | Chlamydiosis |

| BH80 | A1 | JF338858 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | − | + | + | 8 | – | SUG L |

| BH100 | A1 | JF313329 | PsHV-1 | + | + | − | + | + | + | 9 | – | SUG LK |

| BH102 | A1 | JF313330 | PsHV-1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1 | – | SUG LK |

| BH103 | A1 | JF313331 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | + | + | + | 10 | – | SUG LK |

| BH104 | A1 | JF313332 | PsHV-1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1 | – | SUG LSK + chlamydiosis |

| BH107 | A1 | JF338862 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | + | + | + | 10 | – | SUG L |

| BH284 | A1 | JF313333 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | + | + | + | 10 | SUG LK | |

| BH316 | A1 | JF313335 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | − | + | + | 8 | – | SUG L |

| BH318 | A1 | IS | IS | + | − | − | + | + | + | 10 | – | SUG HS + chlamydiosis |

| BH341 | A1 | UR | UR | + | − | − | + | + | + | 10 | – | SUG L |

| BH285 | W | JF313334 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | + | + | + | 10 | – | SUG LS + chlamydiosis |

| BH89 | A1 | JF338859 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | − | − | + | – | SD | UR |

| BH955 | X | JF338870 | PsHV-1 | + | + | − | + | + | + | 9 | – | SUG L |

| BH106 | A1 | JF338861 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | + | + | + | 10 | – | SUG LS + chlamydiosis |

| BH1430 | Y | IS | IS | + | + | − | − | + | + | – | – | Intestinal invagination |

| BH1431 | A1 | JF338875 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | + | + | + | 10 | – | SUG L |

| BH108 | A1 | JF338863 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | − | − | + | – | – | No changes |

| BH958 | Y | UR | UR | − | − | − | − | − | + | – | – | No changes |

| BH342 | A1 | JF313337 | PsHV-1 | − | − | − | − | + | + | 5 | – | Chlamydiosis |

| BH101 | A1 | JF338860 | PsHV-1 | − | − | − | + | + | + | 4 | – | No changes |

| BH1362 | X | JF313326 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | + | + | + | 10 | – | SUG L |

| BH1407 | A1 | JF338873 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | + | + | + | 10 | – | SUG L |

| BH1411 | A1 | UR | UR | − | + | − | − | − | + | – | – | No changes |

| BH1408 | A1 | JF338874 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | − | + | + | 8 | – | SUG LK |

| BH1096 | A1 | JF338872 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | + | + | + | 10 | – | Lipidosis |

| BH343 | A1 | JF338869 | PsHV-1 | + | − | − | − | + | + | 8 | – | SUG L |

| C+ | A1 | PsHV-1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1 | |||

UR, unrealized; IS, incomplete sequence; WCS, without clinical signs; SD, sudden death; SUG, suggestive of viral alterations on liver (L), kidney (K) and spleen (S).

The digestion profiles of isolates KS 144/79 and BH1411 were different from those of the other 27 isolates in group A1, due to the presence of a fragment of approximately 16,500bp long (Fig. 1). The eight remaining isolates revealed three restriction patterns, X, W, and Y, different from those described in the literature (Table 3). The W pattern was represented by a single isolate, and no visible fragments were obtained in a repeated experiment. All other patterns were successfully reproduced.

The dendrogram (Fig. 3) shows two distinct groups, one consisting of the isolates that exhibited the Y pattern and the other consisting of the isolates that exhibited the other three patterns (A1, X and W). Similarity was observed between A1 and X patterns.

PCR amplification patternsUsing this technique, it was possible to identify differences (variants) among 27 of the isolates. Among these, 14 isolates were identified as variant 10, nine as variant 8, six as variant 9, two as variant 1, and one of each as variants 4 and 5, according to the classification strategies detailed by Tomasziewski et al.11 The other nine isolates showed amplification patterns incompatible with any of the variants described in the literature (Table 3).

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysisAll sequences obtained showed 99–100% similarity with the PsHV-1 sequences published in GenBank (Table 3).

Phylogenetic analysis showed four distinct clusters. The first cluster grouped the sequences of the Brazilian isolates and the PsHV-1 sequences obtained from GenBank. It was also possible to confirm high sequence identity (99 to 100%) of PsHV-1 and PsHV-4 (Fig. 4).

HistopathologyThe histopathology results ranged from no observable changes (Nos. 5, 11, 27 and 35) to hepatitis displaying intranuclear inclusion bodies, which suggested herpesvirus infection (Nos. 25 and 26) (Table 3). Among the 26 histologically examined birds, 18 had multifocal lymphoplasmacytic hepatitis with random foci of necrosis suggestive of viral infection. Of these, six displayed additional multifocal interstitial lymphocytic nephritis. Four of these birds showed inflammation in the spleen, characterized by marked histiocytic infiltration with concomitantly diagnosed intracytoplasmic bacteria Chlamydophila psittaci.21 The remaining four birds showed changes unrelated to viral infection.

DiscussionThe RFLP assays were performed using the restriction enzyme PstI, which had been shown to generate the largest number of PsHV profiles.13 These authors observed up to 12 different restriction patterns while testing 31 isolates of PsHV by PstI-RFLP. In our study, five different patterns were observed among the 36 isolates examined by RFLP analysis with PstI. The difference in the number of patterns between the two studies may be due to the fact that the study by Schroder-Gravendyck et al.13 included isolates obtained over a period of 17 years and from different countries, while our isolates were obtained over an eight-month period from the same city/region.

The RFLP pattern generated by digestion of the DNA isolated from strain KS 144/79 showed an unexpected fragment of approximately 16,500bp in length, not observed by Schroder-Gravendyck et al.13 among the products of digestion of DNA from the same isolate with the PstI enzyme. This could be due to an enzyme failure to digest part of the viral DNA or, alternatively, to a mutation in the restriction site that may have occurred during successive passages of the virus in cell culture. This same fragment was also observed among the products of digestion of the BH1411 DNA. With the exception of this fragment, the RFLP patterns of these two isolates were identical to those of the other 27 isolates in the same group and corresponded to the previously described A1 pattern.13

The patterns other than A1, displayed by eight isolates, had no similarity to the 13 other PstI restriction cleavage patterns described in the literature.12,13

Among the three X-pattern isolates, one was obtained from the cloacal swab of a rose-ringed or ring-necked parakeet (Psittacula krameri), a bird naturally found in Africa and Asia, while the other two were obtained from liver and spleen tissue samples of two Brazilian species, a white-eyed Conure (Psittacara leucophthalmus) and a blue-fronted Amazon (Amazona aestiva), respectively. The W pattern was displayed by a unique isolate (No. 32) obtained from the liver of A. aestiva. The four samples that generated the Y pattern were isolated from leukocytes, cloacal swab, and liver tissues of four different bird species, P. krameri, Trichoglossus haematodus, Forpus xanthopterygius, and Eupsittula aurea. Therefore, it was not possible to correlate the differences observed in the RFLP patterns of the isolates based on the bird species or source material.

When the isolates were classified according to the PCR amplification patterns, the results obtained were also different from those reported in the literature. Using this test, Tomaszewski et al.11 were able to identify 10 different variants of PsHV, with variant 1 having been found most frequently. In our study, only six out of the 10 variants were identified (1, 4, 5, 8, 9, and 10), and variants 10, 8, and 9 (in this order) were most prevalent. In addition, nine isolates displayed patterns that had not been previously described in the literature.

The isolates with the A1 RFLP profile displayed all six PCR patterns found in this study and three others yet to be described. The PCR results of the three isolates with the X RFLP profile (Nos. 29, 30, and 31) showed three different amplification patterns (variants 9 and 10 and unknown). Isolate No. 32 (W profile) produced a pattern corresponding to variant 10, while all of the Y-profile isolates generated previously unknown amplification patterns. The latter results might suggest that the isolates produced aberrant patterns of amplification.

Due to the variations in clinical signs and histopathological findings it was not possible to propose correlations between pathogenicity of the isolates and the RFLP patterns. For instance, some psittacine isolates with the A1 profile were obtained from healthy birds, while others were obtained from birds which died and whose histopathology showed hepatitis with intranuclear inclusions, suggesting a viral cause.

RFLP analysis is quite useful to readily determine genotypes of isolates and, therefore, is especially helpful to those working in settings where other techniques, such as DNA sequencing, are not immediately available (for instance, in field laboratories). Nevertheless, future studies employing phylogenetics of complete genomes are essential to further characterize new isolates and discover potential correlations between pathogenicity and RFLP patterns.

In addition to the genetic classification of PsHV, previous studies have also focused on classification based on antigenic variations. Serologically, the viruses have been classified into five serotypes based on cross-neutralization testing. Serotypes 1, 2, and 3 have been considered most common, and serotypes 4 and 5 have been represented by single isolates.10

Previous studies based on sequencing of the 419bp fragment of the UL16 ORF have been able to correlate PsHV genotypes with serotypes. According to these studies, genotype 1 is directly correlated to serotype 1, genotype 2 to serotype 2, and genotype 3 to serotype 3. However, genotype 4 has been correlated to both serotypes 1 and 4. The single isolate representing serotype 5 could not be sequenced, and therefore no correlation with the genotype has been possible.9

Schroder-Gravendyck et al.13 concluded in their study that the A1 restriction cleavage pattern corresponds to serotype 1. Therefore, we can infer that the 29 isolates from this study that showed the A1 RFLP pattern belonged to serotype 1.

Twenty-nine of the isolates used in this study, including some isolates demonstrating the A1, X, W, and Y patterns, had previously been partially sequenced (GenBank accession nos. JF313326, JF313328, JF313329, JF313330, JF313331, JF313332, JF313333, JF313334, JF313335, JF313337, JF313339, JF313340, JF313341, JF338858, JF338859, JF338860, JF338861, JF338862, JF338863, JF338864, JF338865, JF338867, JF338868, JF338869, JF338870, JF338872, JF338873, JF338874, and JF338875). The DNA fragment sequenced is the 419bp fragment corresponding to the UL16 ORF that showed 99–100% identity to the sequences of PsHV-1 present in GenBank.14 Moreover, although the UL16 gene is located in a conserved region within the genome, when the sequences were compared with those of PsHV-2, PsHV-3, and PsHV-4 obtained from GenBank the similarity did not exceed 97%. Therefore, we suggest that all patterns discovered in this study belonged to genotype 1 (PsHV-1) and, probably, to serotype 1.

Phylogenetic analysis showed clustering of the Brazilian isolates with genotype 1 of PsHV. The phylogenetic tree generated indicated the greatest similarity between genotypes 1 and 4 of PsHV. These results are in agreement with the findings of Tomaszewski et al.9 who showed that genotype 4 viruses were most similar to genotype 1, and that the differences between those included a single substitution and six deletions.

The present study described three new restriction profiles of PsHV obtained using PstI-RFLP. We report that the most common variants identified by PCR patterns were variants 10, 8, and 9 (in this order). Our data suggest that the 36 Brazilian isolates studied can be assigned to genotype 1 and serotype 1.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

We thank the entire team of Laboratório de Virologia Comparada – Departamento de Microbiologia – UFMG for assistance during the search. CNPq, CAPES and FAPEMIG for financial support. We also thank to Prof. Dr. Erhard F. Kaleta from Klinik für Vögel, Reptilien, Amphibien und Fische – Justus – Liebig – Universität Gießen for kindly providing the isolate KS144/79 used as positive control.