The growth of the population of cattle egrets (Bubulcus ibis) in the archipelago of Fernando de Noronha constitutes a threat to public health and biological diversity because of their competition with and predation on native species and the possibility of transmission of pathogens to human beings, livestock and native wildlife. The aim here was to search for, isolate and identify serovars of Salmonella in clinically healthy local cattle egrets. Cloacal swabs were obtained from 456 clinically healthy cattle egrets of both sexes and a variety of ages. The swabs were divided into 51 pools. Six of these (11.7%) presented four serovars of Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica: Salmonella serovar Typhimurium; Salmonella serovar Newport; Salmonella serovar Duisburg; and Salmonella serovar Zega. One sample was identified as S. enterica subspecies enterica O16:y:-. Results in this study suggest that cattle egrets may be reservoirs of this agent on Fernando de Noronha and represent a risk to public health and biological diversity.

Exotic invasive species are animals and/or plants that have been introduced into a place where they did not previously exist naturally. They are one of the biggest threats to the environment, causing enormous harm to biodiversity and to natural ecosystems. Furthermore, they may present risks to human health, given that they may transmit diseases to endemic species and cause ecological imbalances.1,2

Fernando de Noronha is an archipelago composed by 21 oceanic islands with 26km2 of total area that are part of the Brazilian state of Pernambuco. They are located in the equatorial zone of the South Atlantic (3°50′28.9″ S, 32°24′39.4″ W), at a distance of 545km northeastwards from Recife, the state capital of Pernambuco. The main island has a resident population of approximately 2930 inhabitants and is designated as a Marine National Park and an Environmental Protection Area.3,4

Among the exotic invasive species seen in the archipelago of Fernando de Noronha, cattle egrets (Bubulcus ibis) have caused emerging problems.2 These include competition for resources and predation of endemic species; potential for transmission of diseases to the human population and production animals; and potential for collisions with aircraft.2,5,6

Cattle egrets belong to the family Ardeidae, order Pelecaniformes. They are insectivorous and are commonly observed foraging in open field areas, close to cattle, and feeding off insects that disturb the cattle.7 The first reports of occurrences of this species on Fernando de Noronha date from the 1980s, and there has been exponential growth of the population since then.2

Among the pathogens transmitted by wild birds, Salmonella spp. has taken on an important role and has even been indicated as a threat to wildlife conservation in general terms.8,9Salmonella belongs to the family Enterobacteriaceae; it colonizes the intestines of reptiles, birds and mammals and has great importance in relation to both human and animal pathology.9,10 Some serovars like Typhimurium and Newport are commonly associated to food poisoning or enteric infection outbreaks worldwide, being a great threat to public health.8–10,24,28,30,32,34

Presence of this genus has been reported in several bird species and groups, such as domestic poultry,11,12 Psittaciformes,13,14 ratites,15,16 raptors,1 Passeriformes18,19 and Ardeidae.8,10,19–23 In cattle egrets, Salmonella has previously been isolated only in the United States.8,19,23,24

Considering the scarcity of studies on isolation of this enterobacteria in cattle egrets, the aim here was to search for, isolate and identify serovars of Salmonella in clinically healthy birds in the archipelago of Fernando de Noronha, Pernambuco, Brazil.

Material and methodsStudy areaThe covered area of the composting unit of waste treatment station in the main island of the archipelago of Fernando de Noronha was used as the site for catching cattle egrets.

Capture, physical restraint, clinical examination and collection of biological materialBetween December 2007 and July 2008, 456 cattle egrets (B. ibis) of both sexes and various ages were caught. The birds were attracted into the covered area of the composting plant by the presence of prey (larvae and insects). They were contained there by closing the doors and were physically restrained by using nets and gloves suitable for the procedure. All the birds were subjected to clinical examination at the time of capture.25 After they had been confirmed as clinically healthy, sterile swabs (CB Products, Corumbataí, São Paulo, Brasil) were introduced into the cloaca of each bird. Those swabs were subsequently kept under refrigeration and sent to the mainland in Styrofoam boxes containing recyclable ice, no more than 48h afterwards, for laboratory procedures to be performed.

Laboratory proceduresThe laboratory analyses relating to isolation and identification were performed in the Infectious-Contagious Diseases Laboratory of the Department of Veterinary Medicine of the Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco (UFRPE). The swabs were divided into pools of not more than 10 swabs, in accordance with the order of capture of the cattle egrets, thus totaling 51 pools. To isolate the agent, the classical scheme for investigating Salmonella recommended by the National Program for Poultry-rearing Health (PNSA) was used. This involved use of 1% buffered peptone water (Oxoid®, Cambridge, England) as a pre-enrichment medium and tetrathionate (Oxoid®, Cambridge, England) and Rappaport-Vassiliadis (Acumedia®, Lansing, Miami, USA) as enrichment broths, with subsequent seeding into brilliant green (Biobrás Diagnósticos®, Montes Claros, Minas Gerais, Brasil) and xylose lysine deoxycholate (XLD) (Oxoid®, Cambridge, England) selective agars. Colonies that were characteristic for Salmonella were crushed into the screening medium TSI (triple sugar iron agar) (Oxoid®, Cambridge, England), which enabled presumptive identification of the genus.26,27

Simplified biochemical profiling was used, consisting of characterization of the isolates according to their capacity for decarboxylation of lysine, use of citrate as the sole source of carbon, mobility and production of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and indole in the following media: lysine iron agar (LIA) (Biobrás Diagnósticos®, Montes Claros, Minas Gerais, Brasil), Simmons’ citrate agar (Oxoid®, Cambridge, England), urea broth, methyl red broth (Oxoid®, Cambridge, England), Voges Proskauer (VP) (Biobrás Diagnósticos®, Montes Claros, Minas Gerais, Brasil) and sulfide indole motility (SIM) agar (Biobrás Diagnósticos®, Montes Claros, Minas Gerais, Brasil).28

After biochemical profile had been confirmed, the samples were sent to the National Reference Laboratory for Enterobacterial Infections (LRNEB) of Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, FIOCRUZ, Rio de Janeiro. At this location, antigen characterization was performed based on serological classification of Kauffmann-White and Le Minor, with representation in accordance with the criteria of Grimont and Weill.29 All the antisera used in the rapid seroagglutination tests were produced by LRNEB.11,26

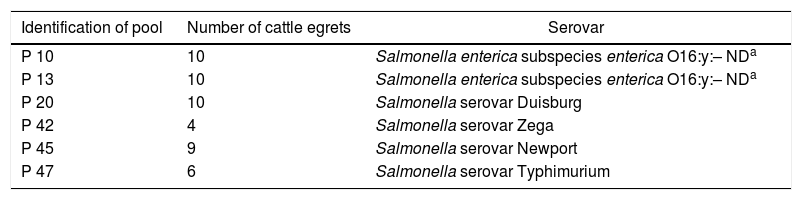

ResultsOut of the 51 pools analyzed, 27 (52.9%) presented colonies suggestive of Salmonella spp. Among these 27 pools, after confirmation through biochemical tests, six (11.7% of the total number of pools) presented test results compatible with the genus Salmonella, and all of these were subsequently confirmed through serotyping (Table 1). Presence of five different serovars was confirmed: Salmonella serovar Duisburg; Salmonella serovar Zega; Salmonella serovar Newport; Salmonella serovar Typhimurium; and one sample that was identified as Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica O16:y:-.

Salmonella serovars isolates from 51 pools of cloacal swabs from cattle egrets (Bubulcus ibis) of archipelago of Fernando de Noronha, Pernambuco, Brazil, 2008.

| Identification of pool | Number of cattle egrets | Serovar |

|---|---|---|

| P 10 | 10 | Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica O16:y:– NDa |

| P 13 | 10 | Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica O16:y:– NDa |

| P 20 | 10 | Salmonella serovar Duisburg |

| P 42 | 4 | Salmonella serovar Zega |

| P 45 | 9 | Salmonella serovar Newport |

| P 47 | 6 | Salmonella serovar Typhimurium |

ND, undetectable (flagellate structure undetectable after phase induction).

None of the cattle egrets presented any clinical signs of salmonellosis, such as ruffled feathers, fever, edema or diarrhea. All the birds presented weights within the normal pattern for this species, ranging from 272 to 543g.

The absence of clinical signs of salmonellosis and the good body scores of the cattle egrets that were caught demonstrated that all of them were clinically healthy. Some of the birds had previously been ringed as part of ecological studies conducted previously by professionals at the Brazilian National Center for Research and Conservation of Wild Birds (CEMAVE). However, no previous studies on infectious or parasitic diseases in these birds on Fernando de Noronha were found.

Most of the studies that have described isolation of Salmonella in cattle egrets were conducted in the United States. In two studies, the genus was identified but not the species or serovar.21,23 Serovars of Salmonella in cattle egrets were described in three studies.8,19,24 Locke at al.8 isolated Salmonella serovar Typhimurium from the internal organs of a single individual cattle egret that had been held in captivity and died at a research center in Maryland. The same serovar was also isolated from other birds in the family Ardeidae that died during the same outbreak of salmonellosis: little blue heron (Egretta caerulea), great egret (Ardea alba), snowy egret (Egretta thula), tricolored heron (Egretta tricolor) and black-crowned night heron (Nycticorax nycticorax). All of these species also form part of Brazilian fauna.5

Phalen et al.24 isolated 30 different serovars of Salmonella in juvenile and adult cattle egrets that were culled for population control purposes at various collection points in Texas, and observed the characteristics of these birds’ bacteremia and death. Callaway et al.19 isolated Salmonella serovar Montevideo from the cecum of cattle egrets, under isolation conditions greatly resembling those of the present study. Serovars isolated from cattle egrets of Fernando de Noronha seemed not to cause illnesses in these birds, which corroborated the findings of Callaway et al.,19 whose study included clinically healthy birds.

Among the Salmonella serovars found in cattle egrets of Fernando de Noronha, the serovar Typhimurium was the only one similar to those found by Phalen et al.24 in the same species in TX, United States. Thus, the present report provides the first description of occurrences of serovars Duisburg, Zega and Newport and of one sample characterized as S. enterica subspecies enterica O16:y:-, in cattle egrets in Brazil, and particularly on oceanic islands.

S. enterica subspecies enterica is frequently isolated from poultry, exotic birds, pigs and chicken carcasses, and has become especially common since the latter part of the 20th century. The serovar Enteritidis is the one most commonly encountered.12,30 On the other hand, S. enterica subspecies enterica serovar O16:y:– has not been isolated in other studies, even from poultry, although some authors have reported isolation of S. enterica subspecies enterica in association with other serovars in poultry and livestock.11,24

Bada-Alambedji et al.31 isolated Salmonella serovar Duisburg from two of the 75 samples that were positive for this genus, from chicken carcasses that were being sold in markets and open fairs in Dakar, Senegal, and other serovars were isolated from the remaining samples. Hoszowsky and Wasyl30 isolated Salmonella spp. from several poultry species such as chickens, turkeys, ducks, geese, pheasants and pigeons and from exotic birds. However, in comparison with the numbers of isolations of other serovars, it was found that the Duisburg serovar had low frequency of occurrence. Like in the present study, the abovementioned two studies did not show any indications of illness caused by this serovar in these birds.

The prevalence of Salmonella serovar Zega in wild birds seems to be low, given the scarcity of studies describing this agent. Even in cases involving humans, the prevalence seems to be low.32 On the other hand, the serovars Newport and Typhimurium seem to be more common and to have greater potential to cause illness in animals and humans.8,10,24,28,32

From the point of view of animal health, cattle egrets habitually come into close proximity to cattle, sheep, goats and horses,6,7 which suggests that they may serve as sources of infection for humans and livestock.5,6 Several authors have suggested that contact between synanthropic birds and poultry production units might be a transmission route for Salmonella to poultry species and consequently to their carcasses.24,31,33

Thus, cattle egrets may perform this role of a source of Salmonella infection on Fernando de Noronha, with dispersion of serovars isolated in this study to the human population and to domestic and wild animals, by means of fecal contamination of food sources or natural and artificial water reservoirs such as millponds, water tanks and cisterns, where these birds habitually land to catch insects and small amphibians. This possibility has already been described by other authors in other localities.5,10,17,25,33,34

Regarding public health, Salmonella spp. has been shown to be the main agent of foodborne diseases in Brazil and worldwide17,24,35 and any of its serovars may be involved in outbreaks of food poisoning infections with mild symptoms.9,12,17,28,30 The serovars described in the present study have little importance as causative agents for non-typhoid enteritis in humans, with the exception of the serovars Typhimurium and Newport, which are commonly associated with this type of illness.8–10,24,28,30,32,34

In relation to biodiversity conservation, pathogenic samples of Salmonella spp. may present risks of high morbidity and mortality among wild animals,9 with consequent loss of genetic variability within populations. This may give rise to even more critical problems for endangered species, thereby accelerating the extinction process.20 Hall and Saito10 cited Ciconiiformes as the order of birds ranked as third most susceptible to death due to salmonellosis. However, regarding salmonellosis or infection by Salmonella spp. in wild birds, the majority of authors have stated that these birds are more commonly asymptomatic carriers.20,22,25 It should be noted that in 2014, the family Ardeidae was relocated from the order Ciconiiformes to the order Pelecaniformes.25

Although the most native marine birds of Fernando de Noronha are not endangered species, infected cattle egrets may have a negative impact through transmission of Salmonella to these species. Through competition for ecological niches with native species, presence of cattle egrets may thus increase the mortality rates among the local avifauna2,5,6 if the Salmonella serovars that they carry happen to cause disease outbreaks in the local populations of wild birds.

Even though there have not been any reports of outbreaks of salmonellosis in the avifauna of Fernando de Noronha, it would be prudent not to dismiss this hypothesis, given that there is no in-depth knowledge of the wild epidemiological chain of this disease in this locality, and considering the pathogenic potential of isolates found in this work.8–10,24,28,30,32,34 Thus, it is possible that cattle egrets really are acting as reservoirs and/or disseminators of these pathogens on these islands. The data obtained in this study are of relevance for public health, since they contribute toward environmental monitoring through knowledge of the epidemiology of Salmonella serovars encountered.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The research was supported by the Administration of Fernando de Noronha, state district, Pernambuco state. The authors are also grateful to the Instituto Chico Mendes para Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio), and to the Laboratório de Enterobactérias of FIOCRUZ-RJ, for serotyping the samples. R. A. Mota, and J. C. R. Silva received fellowships from the National Research Council (CNPq), Brazil.