Arachnoid cysts are dural diverticula with liquid content similar to cerebrospinal fluid, with 1% occurring in the spinal cord. They locate mainly in the dorsal region of the thoracic spine, and are unusual causes of spinal cord compression.

Clinical caseThe case is presented of a previously healthy 15-year-old boy, with a 20-month history of spastic paraparesis that started apparently after epidural block for ankle osteosynthesis. There was decreased sensitivity and strength of the pelvic limbs and gradually presented with anaesthesia from T12 to L4 dermatomes, L5 and S1 bilateral hypoaesthesia and 4+/5 bilateral strength, in the L2 root and 2+/5 in L3, L4, L5, S1, hyperreflexia, Babinski and clonus, but with no alteration in the sacral reflexes. In the magnetic resonance it was diagnosed as an extradural arachnoid cyst from T6 to T9. The patient underwent a T6 to T10 laminotomy, cyst resection, dural defect suture, and laminoplasty. One year after surgery, the patient had recovered sensitivity, improvement of muscle strength up to 4+/5 in L2 to S1, and normal reflexes.

ConclusionsAfter the anaesthetic procedure, increased pressure and volume changes within the cyst could cause compression of the spinal cord, leading to symptoms. Despite being a long-term compression, the patient showed noticeable improvement.

Los quistes aracnoideos son divertículos de duramadre con contenido similar al líquido cefalorraquídeo. El 1% se presenta en la médula espinal; se localizan típicamente en la parte posterior de la médula espinal torácica y son una causa rara de compresión medular.

Caso clínicoSe presenta el caso de un paciente masculino de 15 años, previamente sano, quien acude a valoración por paraparesia espástica de 20 meses de evolución, la cual comienza después de un evento anestésico por osteosíntesis de tobillo. Presenta disminución de la sensibilidad y fuerza de miembros pélvicos, que se incrementa gradualmente hasta presentar anestesia a nivel de dermatomos T12 a L4, hipoestesia L5 y S1 bilateral y fuerza 4+/5 bilateral, en la raíz L2 y 2+/5 en L3, L4, L5, S1, hiperreflexia, Babinski y clonus, sin alteraciones en los reflejos sacros. Mediante resonancia magnética se diagnostica quiste aracnoideo extradural de T6 a T9. Se realizó laminotomía T6 a T10, resección del quiste, cierre del defecto dural y laminoplastia. En el seguimiento a 12 meses el paciente presenta recuperación de la sensibilidad, mejoría de la fuerza muscular hasta 4+/5 en L2 a S1 y normorreflexia.

ConclusionesDespués de la anestesia espinal se produjeron cambios en la presión del líquido cefalorraquídeo y expansión del quiste, lo que desencadenó el déficit neurológico, haciendo evidente su presencia. A pesar del tiempo que se mantuvo la compresión, el paciente presentó una adecuada evolución clínica.

Arachnoid cysts make up 1% of spinal tumours and are defined as diverticula of the dura mater, of the arachnoid or of a nerve root sheath and result from the accumulation of a fluid similar to cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) in the extradural or intradural space.1–5 They are found dorsal to the spinal cord and have been reported in the posterolateral and anterior position.2,6,7 At thoracic level, the spinal canal is relatively small in diameter, and therefore the cysts very frequently present symptoms.7–9

The case is presented of an athletic, previously asymptomatic teenage patient, presenting with progressive neurological deficit in the pelvic limbs, following administration of an epidural anaesthetic for osteosynthesis of the right ankle.

Clinical caseA 15-year-old male patient attended with a 20 month history of spastic paraparesis. On examination he reported that he had been previously healthy with normal psychomotor development. The patient had suffered a fracture to his ankle after direct trauma 20 months previously, which required surgical management with lumber epidural anaesthesia, in a hospital in the north of the country. The patient had lost strength and had developed sensitivity in his pelvic limbs with sensory alteration in his trunk, which the doctors who were treating him attributed to the ankle injury. The patient was reassessed 40 days after surgery by a doctor who attributed the symptoms to poor cooperation on his part and suggested rehabilitation. During these months, his functional limitation affected his daily, sporting and school activities. He reported no alterations in bladder and bowel habits.

The patient's strength gradually lessened, making walking and standing up difficult, which lead to his consulting our institution. On physical examination he was able to walk independently with the help of a walker with front wheels. Initial contact on bilateral forefoot supported on the bilateral medial bar, weak push-off and propulsion phases, steppage pattern, trunk antepulsion, hip semiflexion, recurvatum of both legs, ample support base.

He presented exteroceptive hypaesthesia in all its forms in the root of T11, anaesthesia of T12 to L4 and bilateral hypoaesthesia L5 and S1. His strength was affected bilaterally with 4+/5 on Lucille Daniel's scale in root L2 and 2+/5 in L3, L4, L5 and S1. Patellar hyperreflexia with inexhaustible Achilles’ clonus and bilateral Babinski sign was evoked. He presented weak voluntary anal contraction, with cutaneous anal, external anal, bulbocavernosus and bulboanal reflexes present.

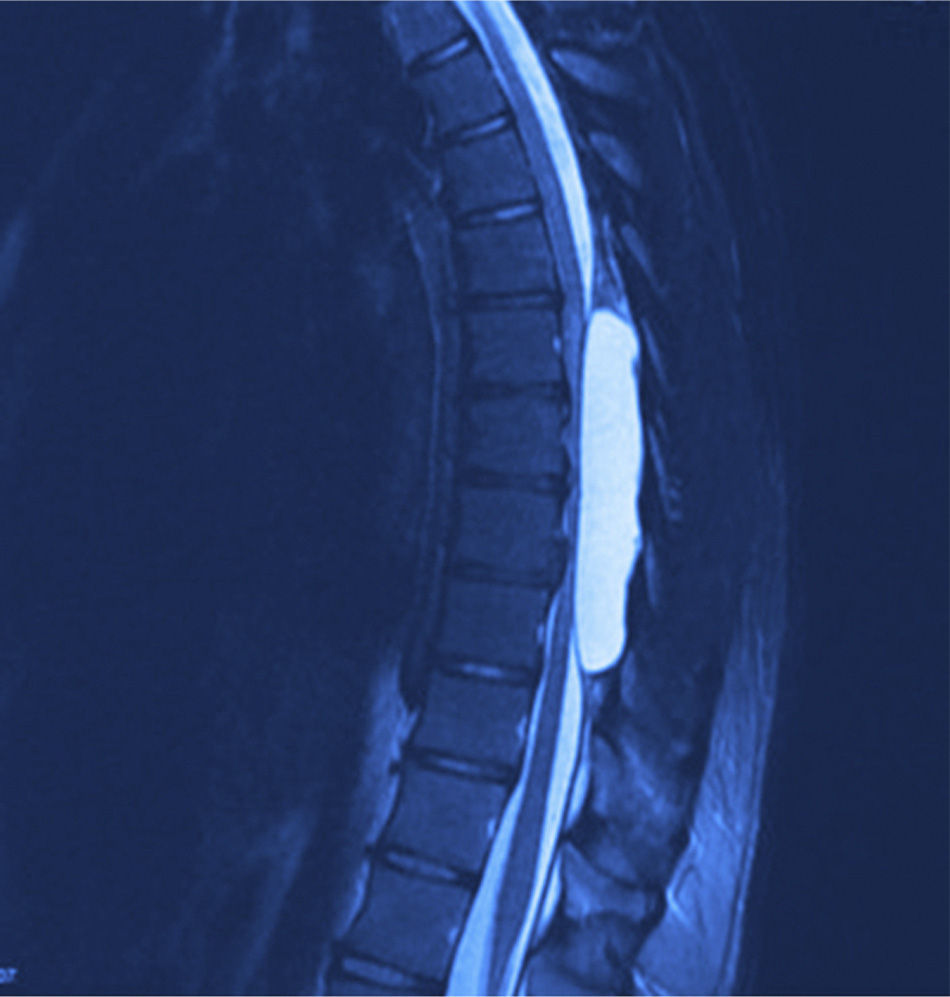

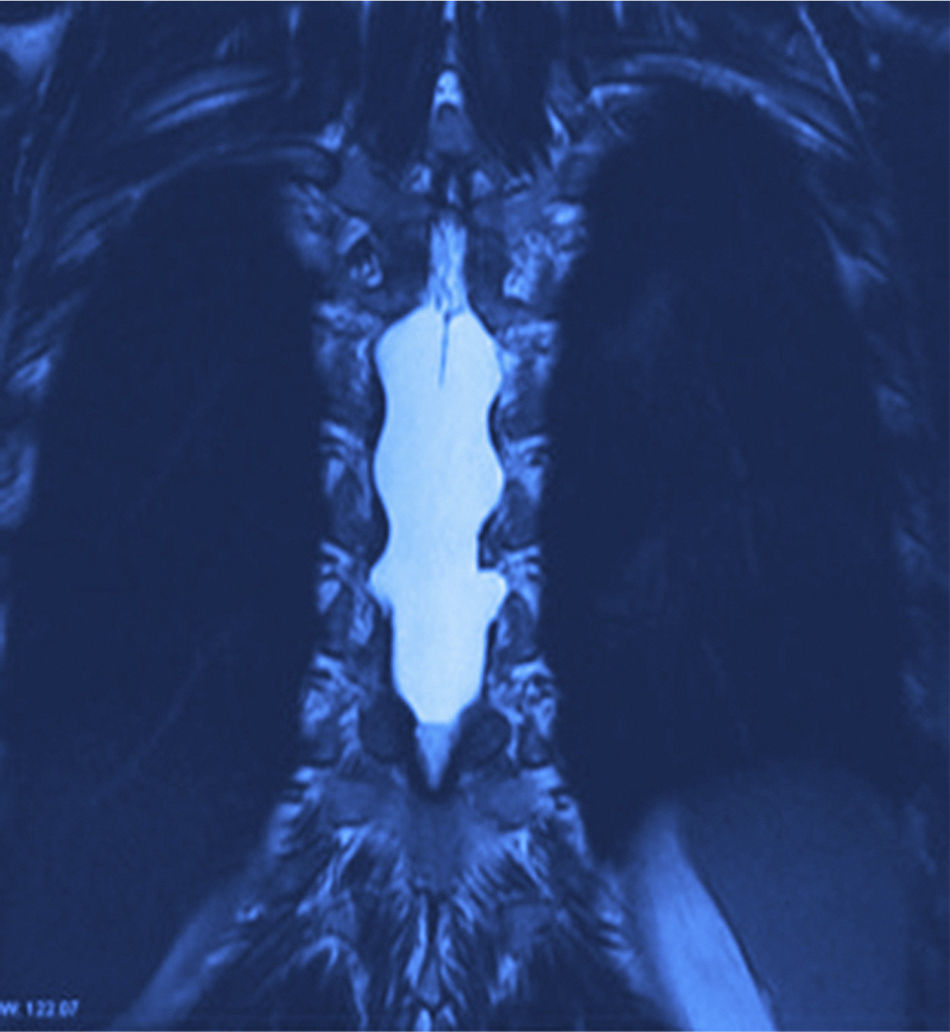

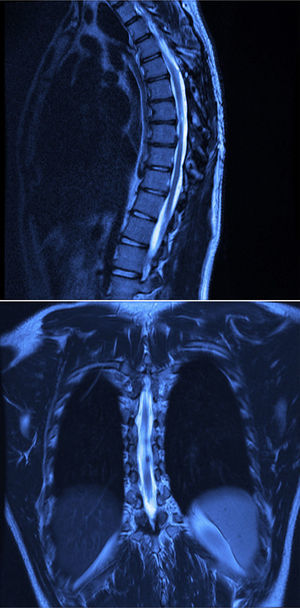

X-rays were taken, showing bony remodelling in the thoracic spinal cord with homogeneous hyperdensity from T6 to T9. MRI (Figs. 1 and 2) showed a wide spinal canal, with moulding of the internal table of the posterior arches by an extramedullary invasive process outside the subarachnoid space, with apparent elongated dissection of the dura and arachnoid, with a diameter of 95mm extending from T6 to T9; the signal intensity in the different sequences corresponds to fluid, without being able to specify of what type as MRI cannot detect this, with no solid component. The spinal cord was displaced and compressed in a dorsoventral direction, with complete invasion of the spinal canal and increased intensity of medullary signal at these levels. The neuroforaminal dimensions were also discretely increased.

A T6 to T10 laminotomy was performed and the spinal canal was examined, finding a cystic lesion under tension with a pedicle in the right dorsal root of T8. A resection was performed with closure of the dural defect and laminoplasty fixing the bone flap with a non-absorbable suture. The fluid aspirated from the cyst was seen to have similar characteristics to CSF. Study of the lesion reported findings consistent with an arachnoid cyst of 4cm×2cm×1cm, greyish white in colour and with a smooth surface.

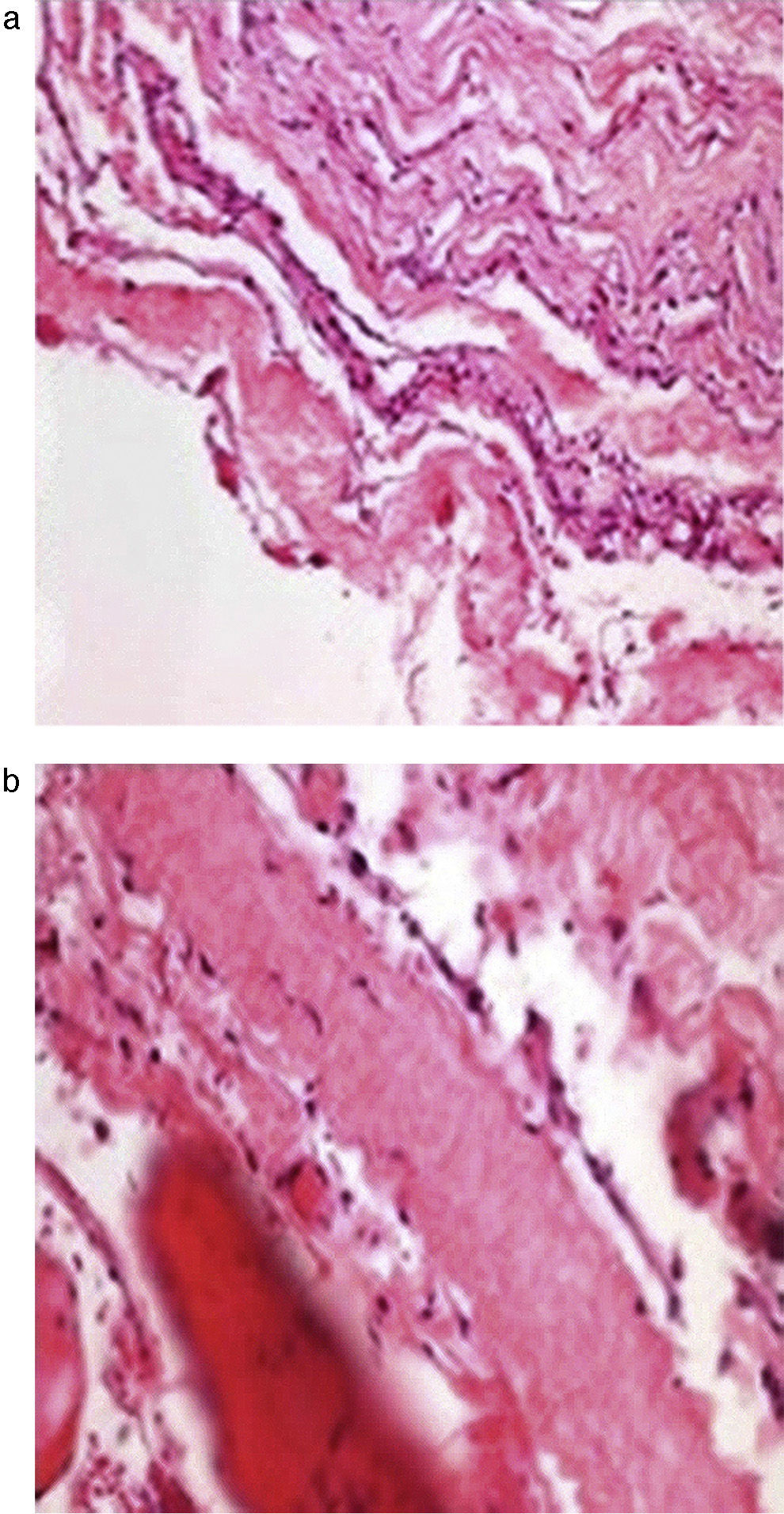

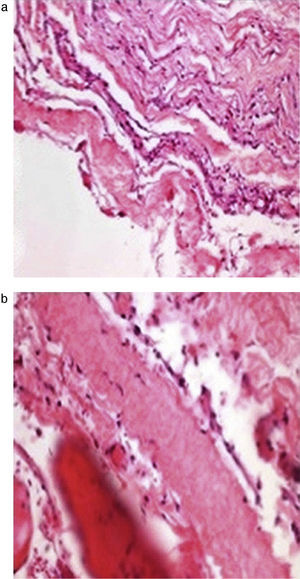

The histopathological study (Fig. 3a and b) showed the walls of the cyst composed of fibro-connective tissue, with meningothelial-like cells, collagen fibres, fibro-adipose tissue and striated skeletal muscle.

One month afterwards, the patient started intensive rehabilitation; increased muscle strength, reduced contractions, improved balance and re-educating the gait were the prime objectives.

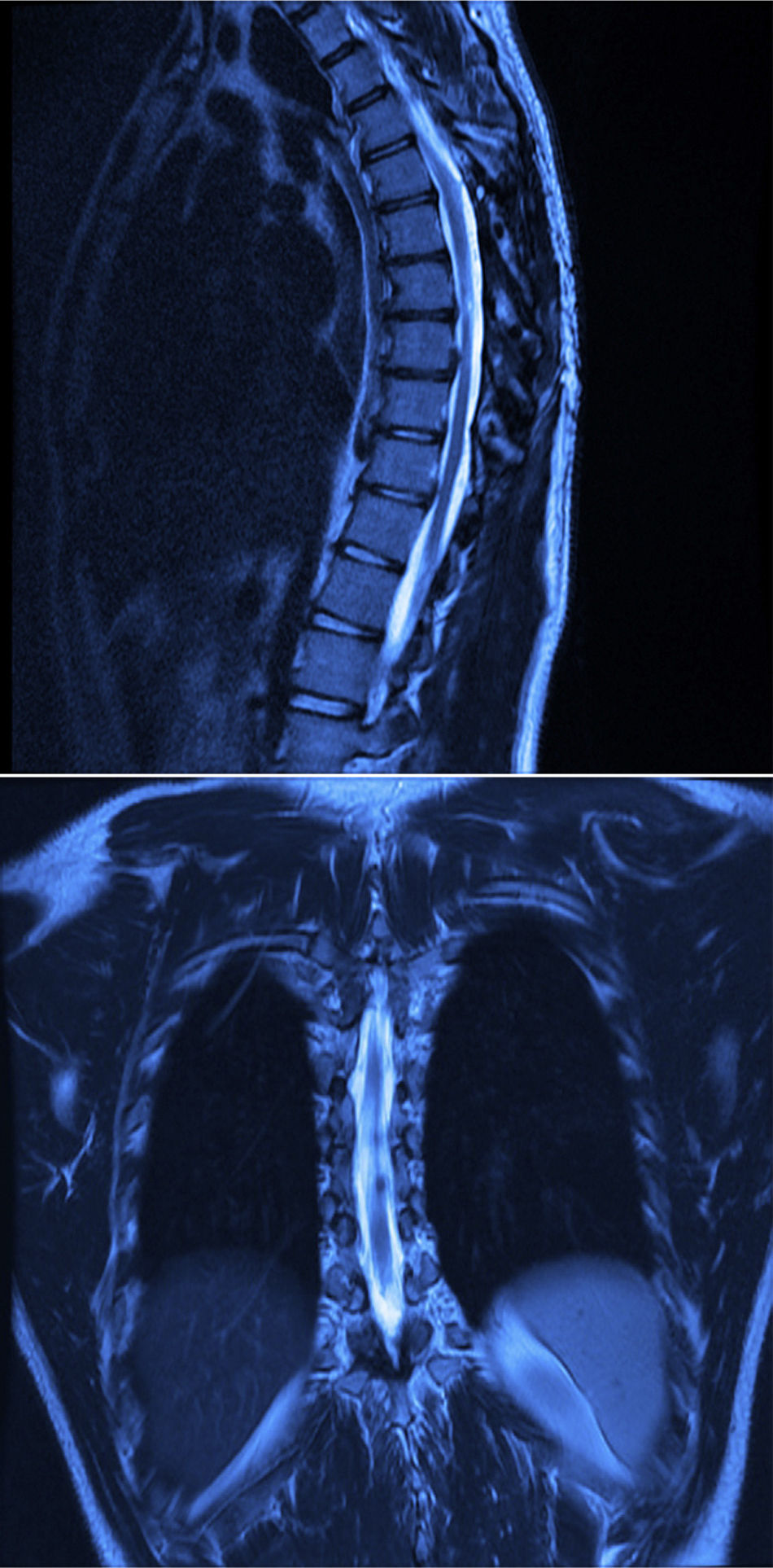

Twelve months after surgery the patient was able to walk independently, had a good heel-to-toe gait pattern, superficial sensitivity and pain-touch discrimination preserved distally from T6, muscle strength 4+/5 on Lucille Daniels’ scale in the root L2 to S1, normal patellar reflex and bilateral hyperreflexia of the Achilles tendon. The lesion had not recurred at one year, according to MRI (Figs. 4 and 5).

The patient still presents motor deficit in both pelvic limbs that mildly affects his movement. However, he has overcome his disadvantages compared to his peers in terms of social, family and school life and is waiting to resume his recreational and sporting activities.

DiscussionArachnoid cysts are benign tumours which occur in the cerebrospinal axis of the arachnoid membrane.10 Historically the first arachnoid cyst was detected by Schlesinger in 1893, and the first report was by Spiller in 1903.11 They present more commonly in men, in the second decade of life.12,13 They often present in the mid and lower thoracic region (65%), in the lumbar and lumbosacral (13%), thoracolumbar (12%), sacral (7%) and cervical spine (3%).13

Extra-dural cysts result from a protrusion of the arachnoid membrane that communicates with the subarachnoid space through a defect in the dura mater,10 they are the rarest type of cyst and can be single or multiple.14,15 Nabors et al.16 categorise arachnoid cysts as: Type I, spinal extradural meningeal cysts without spinal nerve root fibres; Type IA, extradural arachnoid cysts; Type IB, sacral meningoceles; Type II, spinal extradural meningeal cysts with spinal nerve root fibres; Type III, spinal intradural meningeal cysts.

Five mechanisms of formation have been proposed:

- 1.

Congenital causes, associated with neural tube defects and syringomyelia. Lake et al.17 postulated that the cysts originate from arachnoid trabeculae which dissect dorsally in the subarachnoid space of the midline the length of the spinal canal or near to the nerve root. Perret et al.18 demonstrated that intradural cysts are the result of a widening of the septum posticum, and CSF pulsations that dilate the weak areas of the arachnoid to form dorsal cysts. However, none of these theories explain the formation of ventral cysts. Cadaver studies confirm that the dorsolateral septa are different at thoracic level because the dorsal roots descend more obliquely causing a transverse arachnoid wall to form in the subarachnoid space when the dorsolateral septa fuse in the midline; this might be the origin of arachnoid cysts.19 Another theory is that during the embryonic period herniation takes place of the arachnoid membrane through a defect in the dura mater, secondary to medullary dysraphism.15

- 2.

Secondary to an inflammatory process caused by a virus, spirochaete or bacteria.

- 3.

Arachnoiditis secondary to subarachnoid haemorrhage.

- 4.

Traumatic injury to the spine, lumbar punctures. Lee et al.20 demonstrated that tensile strengths between the mobile thecal sac and the fixed nerve roots cause injury to the dura mater. If there is a previous structural problem in the thecal sac, movement or trauma will cause the injury to the dura mater to increase volume and pressure, encouraging the formation of a cyst.

- 5.

Idiopathic aetiology.

Three theories have been given as to how the cyst fills.

- 1.

By the active secretion of fluid from cells in the cyst wall. Berle et al.21 postulate that the filling mechanism is by selective or active transport or by secretion from the cells lining the cyst. In their study they found isotonic fluid with a low concentration of proteins inside the cyst compared to that of CSF, which might imply active or selective transport of the fluid over the cyst membranes. The phosphate level in CSF is lower than in the peripheral blood due to the activity of transporters in the choroid plexus epithelium. Greater amounts of phosphate in the cyst fluid imply that its epithelium presents transport mechanisms similar to those of the choroid plexus.22 This is consistent with discoveries of ultracytochemical and morphological enzyme structures in the cyst wall that are able to secrete fluid. Aarhus et al.23 published that in the cyst, the cotransporter NKCC1 (an isoform of the membrane transport protein which carries a sodium, a potassium and 2 chlorides) is up regulated and a reduction of protein complexes is observed. It has also been reported that cotransporters such as GLUT1, MCT1 and NKCC1 have the ability to transport water the length of their respective substrates, despite the osmotic gradients.21–23

- 2.

Increased oncotic pressure. This theory suggests that during the embryonic period there is a proliferation and pathological distribution of the trabecular cells of the arachnoid, which subsequently degenerate and increase the oncotic pressure inside the cyst.15

- 3.

Valve mechanism. It is postulated that there is anatomic communication through a one-way valve between the subarachnoid space and the cyst.18 It may seal in a subsequent phase of its development, to constitute a noncommunicating arachnoid cyst.24 Paravertebral extensions are triggered by this mechanism, causing expansion through the foramina and areas of least resistance of the cruciate ligament.24

On histological examination, the lining cells present fibrocartilaginous tissue, meningoepithelial cells, inflammatory cells and on occasion, arachnoid tissue.25

Clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatmentThe symptoms presented are fluctuating and are a consequence of hydrostatic pressure changes of CSF, which in turn, cause pressure changes inside the cyst, and therefore are exacerbated by postural changes, physical exercise and/or Valsalva manoeuvre.15,25 These symptoms can be back pain, sensory changes, urinary dysfunction and weakness.7,17,19 Myelopathy, spinal cord compression, cauda equine symptoms, flaccid or spastic paralysis.14,16,24

X-rays show indirect signs of mass effect, such as: an enlarged spinal canal, bone erosion, thinning of the pedicles, widened foramina or increased interpedicular distance.26

Magnetic resonance is the gold standard for diagnosis. Cysts are seen as isointense to CSF, hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2, and they do not enhance with contrast. Similarly, the degree of atrophy and the extension of myelomalacia can be observed.19,24

Patients with pain and neurological deficit are candidates for surgery.27 There are various techniques; however, there is no consensus on surgical management.14 Laminoplasty offers the required exposure and decompression of the spinal canal, while maintaining the stability of the spine and the integrity of the posterior elements.28 Complete surgical resection,6 followed by obliteration of the communicating pedicle and repair of the dural defect, is curative in most cases and presents an improvement in neurological function.12 Lee et al.20 reported lower recurrence after repair of dural defect; surgical management techniques include marsupialisation or fenestration and dural defect repair.18,29 In laminoplasty reports, 2% of patients presented recurrence after repair of the dural wall, whereas 66.7% of those who did not undergo repair of the defect presented recurrence.20 Of those who underwent total resection of the cyst or fenestration, 8.3% and 3.6% presented recurrence, respectively.29 Finally, drainage of the cyst inside the subarachnoid space has been described with good temporary results.13,29

The incidence of deformity after laminectomy is from 33% to 100%, and therefore laminoplasty is preferred.29 Some factors which can result in postoperative deformity include: being under the age of 3, pre-existing deformity, decompression that spans the cervical spine of the cervicothoracic region, removing 3 or more laminae and intensive facectomy.

Surgery provides unfavourable results in elderly patients, with long duration of paresis and thinning of the spinal cord due to the presence of the cyst, which causes permanent vascular insufficiency due to prolonged compression.6,25 Neurological recovery depends on the size of the cyst and the extent and duration spinal cord compression, therefore a high degree of suspicion is vitally important and appropriate, timely treatment.27

There is a similar report to ours, of a female student presenting with back pain and fever a day after an epidural block at level L4–L5 for a caesarean section. The patient had a history of chronic back pain and morbid obesity. She was diagnosed with an 8mm thoracic arachnoid cyst with no presence of oedema or compression, and she did not present neurological deterioration. She was kept under observation with conservative management.30

ConclusionsArachnoid cysts are rare disorders which are diagnosed incidentally. Their aetiology is uncertain and although most are asymptomatic, in patients who develop spinal cord and nerve compression, their impact can be major in biological, psychological, social and economic terms.

We can clarify that our patient's cyst was of congenital origin, since he had no history of trauma, surgery or infection, or prior lumbar or thoracic symptoms. We suggest that after the spinal anaesthetic changes in CSF pressure were produced and expansion of the cyst, which triggered the neurological deficit, making the presence of the cyst evident. Despite the duration of the compression, the patient had a good clinical outcome, probably because he was young and had been healthy previously.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Obil-Chavarría CA, García-Ramos CL, Castro-Quiñonez SA, Huato-Reyes R, Santillán-Chapa CG, Reyes-Sánchez AA. Presentación clínica de quiste aracnoideo epidural dorsal posterior a anestesia epidural. Cir Cir. 2016;84:487–492.