Lymphangiomas are benign tumours, considered to be congenital malformations of the lymphatic system that predominately affect children, with only a few cases reported in adults. The most common sites of these lesions are the neck (75%) and axillary region (20%), but rarely found in the spleen.

ObjectiveA description is presented of 3 cases of incidentally detected splenic lymphangioma, one in a child and in 2 adults, respectively, as well as a literature review.

Clinical casesAfter a clinical and physical examination, all patients had an abdominal ultrasound, CT scan and a complete splenectomy, followed by a histopathological study on the removed spleen. Two patients were asymptomatic, and the paediatric patient referred to intermittent abdominal pain without other symptoms. The clinical and physical examinations related to the mass were negative. The final diagnosis was based on a combination of radiological and histopathological findings. Total splenectomy was undertaken in all cases without complications.

ConclusionsSplenic lymphangioma is very rare, and more so in adults. This condition is often asymptomatic and is incidentally detected by imagenology due to any other different cause. The final diagnosis should be based on a combination of clinical, radiological, and histopathological findings. Splenectomy is the treatment of choice and the prognosis is good.

Los linfangiomas se originan por una malformación congénita del sistema linfático que, en general, afecta a niños y muy poco a adultos. Se localizan habitualmente en el cuello (75%) y axilas (20%), pero también pueden aparecer en otras localizaciones; muy raramente en el bazo.

ObjetivosPor su rareza, se presentan 3 casos de linfangiomas esplénicos (un paciente pediátrico y 2 adultos) y se revisa esta enfermedad.

Caso clínicosLos 2 pacientes adultos estaban asintomáticos; el otro, pediátrico, refería crisis de dolor abdominal, sin otra sintomatología. En los 3 pacientes se realizaron ecografía y tomografía computada abdominal, esplenectomía completa y estudio histopatológico del bazo extirpado. En los pacientes asintomáticos, el linfangioma fue descubierto de modo incidental en el curso de otra enfermedad. En los 3 casos, el diagnóstico fue realizado por la combinación de estudios de imagen e histopatológico. La clínica y examen físico respecto al efecto masa fueron negativos. Se realizó esplenectomía completa en los 3 casos sin complicaciones.

ConclusionesEl linfangioma esplénico es muy raro, más en adultos. Con frecuencia es asintomático y es detectado de modo fortuito por estudios de imagen realizados por otra causa. El diagnóstico final debería estar basado en la suma de los datos clínicos, radiológicos e histopatológicos. El tratamiento de elección es la esplenectomía y el pronóstico es bueno.

Lymphangiomas are benign tumours, considered to be congenital malformations of the lymphatic system which predominantly affect children and very rarely affect adults. They are generally located in the neck (75%) and axillary region (20%), but they can appear in other locations, very rarely in the spleen.1–5 One hundred and eighty cases of splenic lymphangioma have been published from 1939 to 1990, and only 9 cases from 1990 to 2010.6

Lymphangiomas are benign tumours which arise from a congenital malformation of the lymphatic system in which obstruction or agenesis of lymphatic tissue causes a lymphangiectasia secondary to the absence of normal communication between the lymph ducts, which terminate in a cul-de-sac and slowly dilate until a cyst is formed.1,7 Most lymphangiomas appear in the neck and axillary region (95%), where they are termed cystic hygroma. All the other locations, including the abdomen, are rare, comprising 5% of all cases.5–8 Benign primary tumours of the spleen are found in 0.007% of all autopsies and surgical interventions.9

Splenic lymphangiomas are very rare. In general they occur in children (80–90%) and are an incidental finding8,10; they present more often in women, in 80–90% they are diagnosed in infancy and the great majority are detected before 2 years of age.11 Histologically, lymphangiomas are classified, according to the size reached by the lymph ducts, into 3 subtypes: capillary (supermicrocystic), cavernous (microcystic) or cystic (macrocystic). The lymphangioma can be single, small and subcapsular, although it can also be multicystic. In the latter case it is often associated with other diseases.1,12

Splenic lymphangioma can be asymptomatic and be diagnosed during abdominal surgery performed for a different reason, it can be detected in the anatomopathological study of the removed spleen or can cause splenomegaly or have large elements; in the latter case it can be complicated with haemorrhage, consumptive coagulopathy, hypersplenism and even portal hypertension.13,14 The symptomatic cases present pain in the left hypochondrium due to splenomegaly and the pressure that the cyst exerts on the closest organs.15 It is often followed by fever, nausea, vomiting, anorexia and weight loss,6 this opinion is not shared by some3; pain in the left shoulder and constipation are rare. Given the similarity of signs and symptoms, the diagnosis is often confused with hydatid disease where a negative E. granulosus agglutination test result does not always exclude this diagnosis. Although an exact diagnosis can only be made by histopathological study of the removed spleen,14,15 the final diagnosis should be based on the sum of all the clinical, radiological and histopathological data. Occasionally asymptomatic patients attend consultation because they have noticed a painless abdominal mass, which has recently grown and is easily palpable on physical examination.16,17 Eventually, the effect of an abdominal mass produced when the spleen reaches 3–4kg in weight can cause diaphragmatic immobility and consequent atelectasis or pneumonia.3,17 If the lymphangioma partially affects the spleen, no haematological changes present, and if it is diffuse and affects the entire spleen, it causes the phenomenon of splenic sequestration which manifests with anaemia, granulocytopenia and thrombocytopenia.1,17

ObjectiveThis study presents 3 cases of splenic lymphangioma, one paediatric patient and 2 adults, discovered incidentally, and reviews the disease.

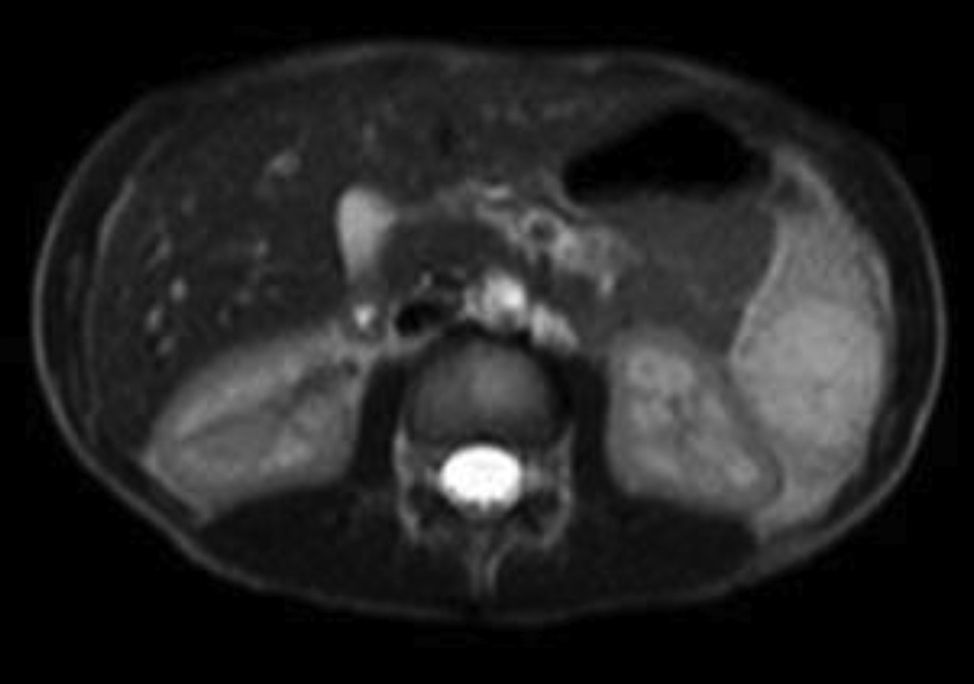

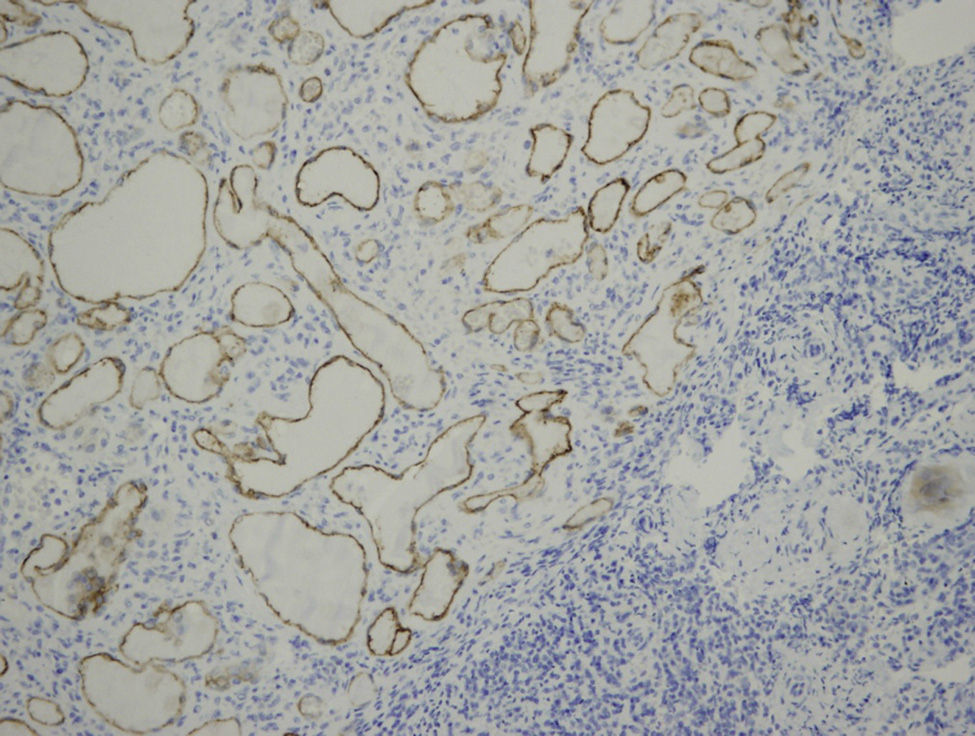

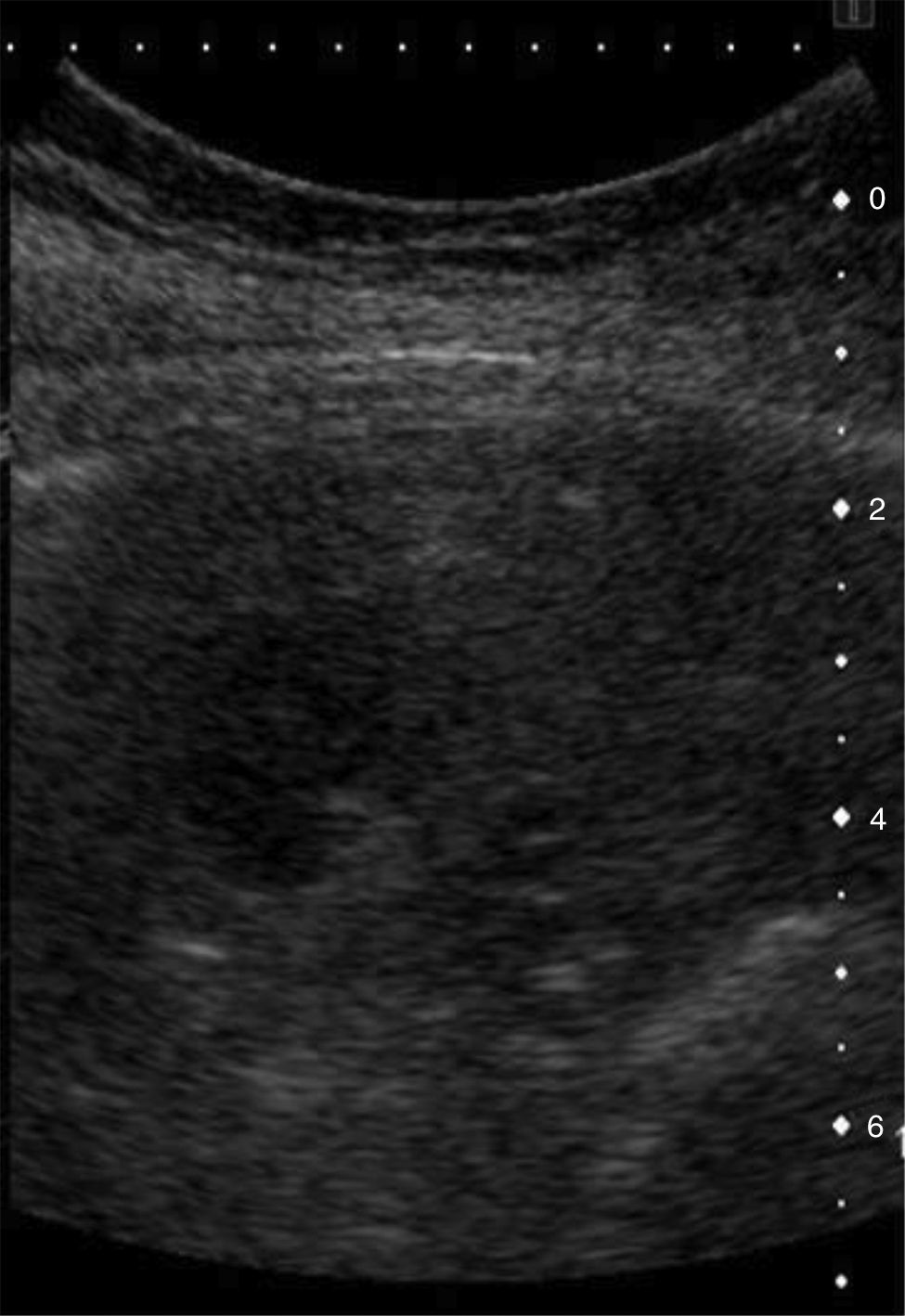

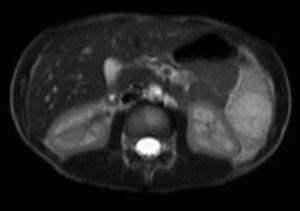

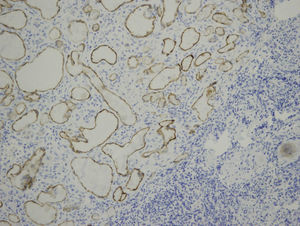

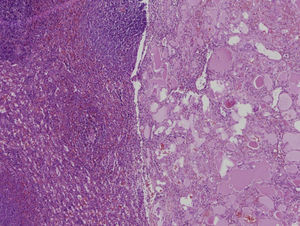

Clinical casesCase 1Male, 6 years of age, reporting intermittent abdominal pain in episodes related to the intake of food; normal bowel movements and no other symptoms. No personal history of interest. Normal physical and laboratory examination. No changes on chest X-ray. Abdominal ultrasound: splenomegaly of 11cm with a non-specific focal lesion in the lower margin of 3.6cm×3.5cm, not very vascularised (Fig. 1). Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging showed 3 splenic focal lesions: one of 1.2cm on the medial face of the lower third, another of 2.6cm on the lower anterior section and another of 3.3cm on the lower pole, bulging out the surface of the spleen (Fig. 2). They are slightly hyperintense on T1, hypointense on T2, with septums in their interior, which after administration of gadolinium, patchily enhance on the periphery. No changes on the rest of the abdomen. Treatment: total laparoscopic splenectomy, without incident. Post splenectomy prophylaxis. Anatomical pathology: a spleen 81g in weight, with 3 nodular lesions of the splenic parenchyma of 1.5, 2 and 3cm, respectively; brownish in colour and increased consistency comprising multiple small and medium-sized vessels containing serous material (proteinaceous and eosinophilic) in their interior and coated by flat endothelium without cytological atypias, in some cases forming small plume formations comprising cells without atypia. There are fine partitions of connective tissue between the vessels and remains of splenic red pulp, with no mitosis or foci of necrosis. The remaining splenic parenchyma did not show microscopic lesions. The vascular endothelium was marked with antibodies against CD34, CD31 and D2-40 by means of immunohistochemical technique (Fig. 3). Diagnosis: multiple splenic lymphangiomas.

Abdominal MR: 3 splenic focal lesions, one of 1.2cm on the medial face of the upper third, another of 2.6cm in the lower anterior section and another of 3.3cm on the lower pole, bulging out the surface of the spleen. They are slightly hypointense on T1, with some septums in the interior. There are no alterations in the remainder.

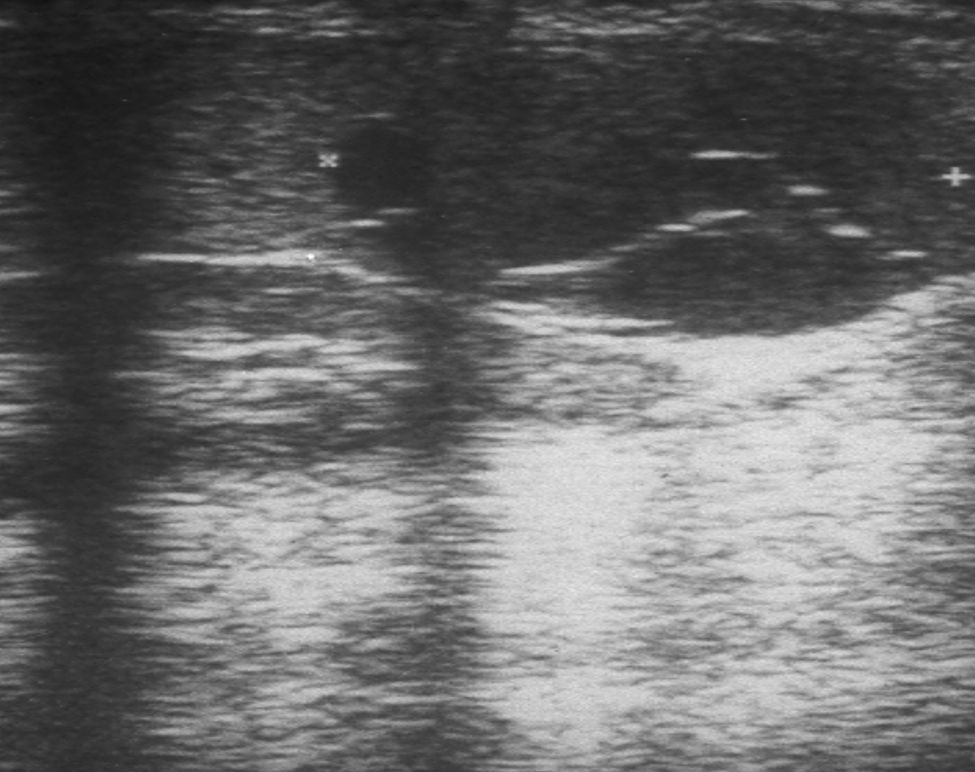

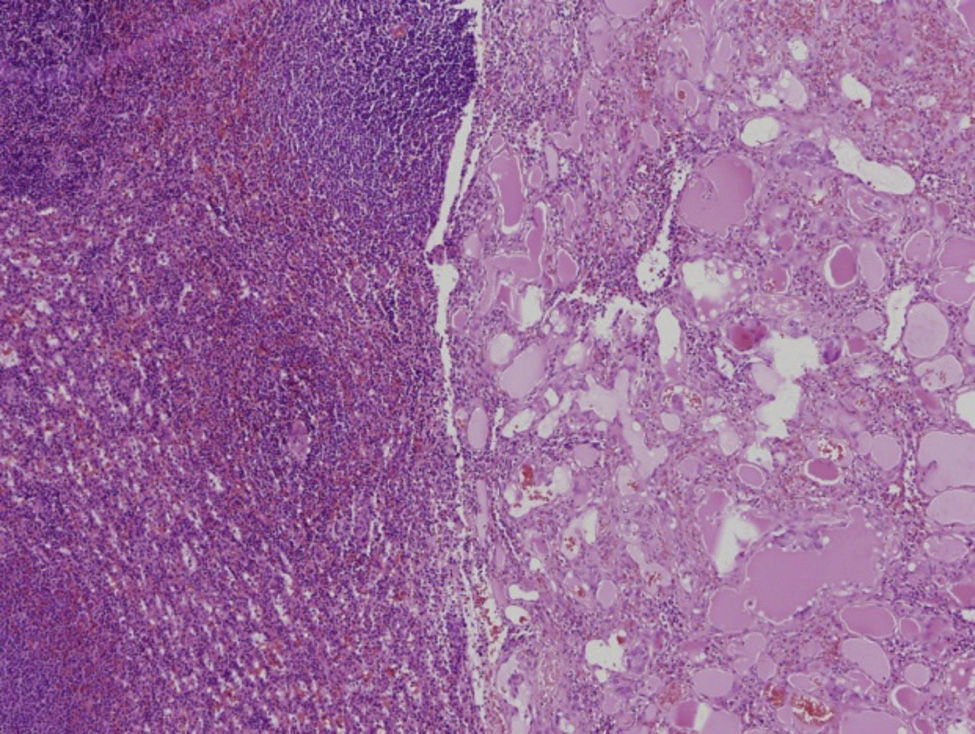

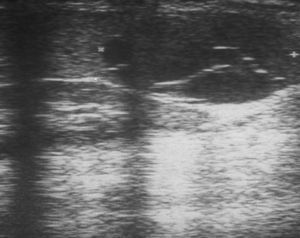

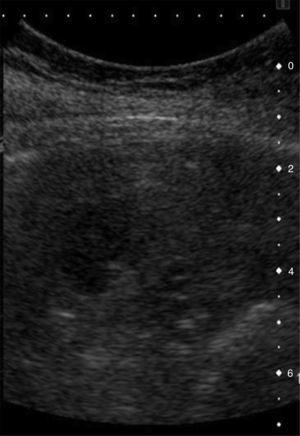

A 28 year-old woman admitted to the Internal Medicine Unit with uncontrolled arterial hypertension. Abdominal ultrasound showed esplenomegaly of 13cm and a splenic lesion of 1.2cm×1.4cm poorly vascularised (Fig. 4). CT scan showed a left suprarenal tumour of 14cm, causing for Cushing's syndrome, and a lesion of clear contours in the spleen, 12mm in diameter, of less attenuation value than the remainder of the splenic parenchyma. A left suprarenalectomy and total open splenectomy was performed. Post splenectomy prophylaxis. Antero-posterior: spleen of 230g in weight measuring 12.8cm×9.4cm presenting a nodular formation brownish in colour and with proteinaceous content comprising multiple prolongations of lymphatic elements covered by flat endothelium without cellular atypias (Fig. 5). Diagnosis: suprarenal carcinoma and single splenic lymphangioma.

Case 3A 70 year-old woman, mastectomised 4 years previously, who was admitted for elective splenectomy for suspected “metastatic nodules” in the spleen detected by contrast ultrasound (Fig. 6) and computed tomography. After preoperative study a classic open splenectomy was performed without incident. Antero-posterior: spleen of 380g measuring 13.5cm×9.4cm and presenting various nodular formations on the surface, translucent and containing mucoid material, the largest measured 8mm in maximum diameter, comprising cystic proliferations of lymphatic elements covered by flat endothelial cells; most appeared stained by acellular acidophilic material. Diagnosis: multiple splenic lymphangiomas.

DiscussionSplenic lymphangiomas are predominantly found in children and are generally diagnosed before the age of 2 (80–90%),8,10,11 when a surgical procedure is performed for a different reason, as they are generally asymptomatic, or they can cause splenomegaly which can be complicated by haemorrhage, consumptive coagulopathy, hypersplenism and even portal hypertension.13,14

For the diagnosis of splenic disease, the imaging studies are abdominal ultrasound, computed tomography and magnetic resonance. Ultrasound is useful as an initial test in the diagnosis of splenic cysts; however, it does not delimit the topography of the lesion,1,17 although contrast ultrasound enables these lesions to be better evaluated. Computed tomography, by contrast, not only shows the topography of the lesion, but also its size, nature and anatomical relationships.7,17–19 Magnetic resonance has no more advantages than computed tomography, except that it avoids radiation to the patient. Ultrasound and computed tomography are the tests of choice for diagnosis and for planning the surgical strategy.18 Radiological study shows splenomegaly or a normal-sized spleen, curvilinear calcifications in the cystic wall or mass effect on the adjacent viscera. Ultrasound shows well-defined hypoechoic cystic lesions with some septums in their interior, as in our case 1, and some echogenic calcifications. Colour Ecco Doppler can demonstrate vascularisation of the cyst, including the intrasplenic arteries and veins throughout the walls of the cyst.9,12 In computed tomography, lymphoangiomas appear as single or multiple masses with well-defined, typically subcapsular margins, sometimes the largest cyst is surrounded by small satellite lesions that when accompanied by peripheral wall calcifications, suggest a diagnosis of cystic lymphangioma.8,19 The differential diagnosis of splenic lymphangioma includes other solid and cystic lesions such as haemangiomas, splenic infarction, septic embolism, chronic infection, lymphoma and metastasis. According to the Pearl-Nassar classification, there are only 3 types of cystic lesions: parasitary cysts; the first with epithelial covering (dermoid, epidermoid or transitional) or endothelial covering (haemangioma or lymphangioma) and the second or traumatic cysts, which have no endothelial covering.20 In recent years, image-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy has been increasingly used in a great variety of benign and malignant splenic lesions. A general consensus has been reached on the efficiency and safety of this procedure, despite the false-negatives obtained, with an incidence varying between 0.06% and 2%,21,22 and the risks of haemorrhage.

The treatment of splenic lymphangiomas depends on their size; traditionally, large and symptomatic lesions have been treated by total splenectomy via median or left subcostal laparotomy,7,17 as was performed on 2 of our patients. However, since the first laparoscopic splenectomy of a cystic lymphangioma performed by Know et al. in 2001,16 several authors propose the laparoscopic route as the technique of choice to approach these tumours of the spleen,23–25 as was performed on one of the cases that we present, splenomegaly is considered a contraindication for this approach.6 although many surgeons recommend total splenectomy as standard treatment of tumours of the spleen,1,7,17,18,26,27 the objective of resection of benign tumours should be local exeresis of the tumour, preserving as much splenic parenchymal mass as possible or even the entire spleen in order to prevent the sequelae of asplenia .17,23,26,27 During surgery, open or laparoscopic, accessory spleens should be looked for, and if there are any they should be removed as they can form part of the process. Surgery should be performed without delay, unless the cyst is infected or there is any other circumstance which contraindicates it.28 The rates of recurrence and malignancy are low and the prognosis is good, although there are some cases of lymphangiomas becoming malignant lymphangiosarcomas. Conservative treatment of splenic lymphangioma with interferon-alpha was used successfully in a child by Reinhardt et al.29 and was well tolerated; however, the optimum time and dose to cure this disease indefinitely is not known.

Splenic lymphangiomas are thin-walled cysts with trabeculated and fibromuscular internal morphology, covered in endothelium and full of eosinophilic proteinaceous fluid.1,7,8,17,18 Lymphatic spaces are found on the wall of the lymphangioma, lymphatic tissue and smooth muscle fibres,18 these features are present in the lymphangiomas which we studied. The subcapsular location of a lymphangioma is the most common, the intra-parenchymatous location being rarer.8 Immunohistochemical confirmation of lymphangioma is by reaction to factor viii and the specific D240 endothelial marker.8 Histological study of the abovementioned nodules easily excludes a suspected diagnosis of parasitic cysts and establishes the vascular origin of the lesions.

ConclusionsSplenic lymphangioma is very rare, more so in adults. It is often asymptomatic and is discovered by chance on imaging studies performed for a different reason. Contrast ultrasound enables better identification of these tumours. The final diagnosis should be based on the sum of the clinical, radiological and histopathological data. The treatment of choice is splenectomy and the prognosis is good.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-Montes JA, Collantes-Bellido E, Marín-Serrano E, Prieto-Nieto I, Pérez-Robledo JP. Linfangioma esplénico. Un tumour raro. Presentaciónde 3 casos y revisión de la bibliografía. Cirugía y Cirujanos. 2016;84:152–157.