Nephron-sparing surgery is currently the treatment of choice for surgical removal of solid renal tumours smaller than 7cm, in the case of a solitary kidney, bilateral renal tumours or the presence of chronic renal failure.

Material and methodsAn observational, descriptive, retrospective and cross-sectional study was conducted. The variables evaluated were: age at diagnosis, gender, intraoperative blood loss, operative time, preoperative tumour size, hospital stay, pathology report, pTNM classification, Fuhrman nuclear grade, pre- and post-operative creatinine, monitoring for cancer. All were analysed using SPSS v 22.

ResultsThe study included 28 patients, 14 male and 14 women, with a mean age 52.3 years. The approach was lumbotomy in all patients. The mean hospital stay was 4.1 days. Mean perioperative bleeding loss was 380.3ml. The mean preoperative creatinine was 0.96mg/dl, with a post-operative mean of 1.12mg/dl. Histopathology reported, 23 clear cell tumours, 2 angiomyolipomas, 2 oncocytomas, and 1 haemorrhagic cyst. Tumour staging was performed on 14 patients, with 13 patients T1bN0M0, and 1 patient T2aN0M0. In clear cell tumours, Fuhrman nuclear grade 2 was present in 16 patients and 7 patients were Fuhrman grade 3.

ConclusionNephron sparing surgery is the choice procedure of choice in patients with small renal tumours, with good functional results without significant alteration in renal function. Outcome is optimal, with a low incidence of complications.

La nefrectomía radical es considerada el estándar de oro para el tratamiento de tumores renales. Sin embargo, la cirugía preservadora de nefronas es una opción quirúrgica en pacientes con tumores renales menores de 7cm, con riñón único, tumores renales bilaterales o con insuficiencia renal crónica.

ObjetivoDescribimos la experiencia en cirugía preservadora de nefronas en pacientes con tumores renales pequeños (<7cm).

Material y métodosEstudio observacional, descriptivo, retrolectivo y transversal. Variables estudiadas: edad al diagnóstico, género, sangrado transoperatorio, tiempo quirúrgico, tamaño tumoral prequirúrgico, estancia intrahospitalaria, resultado histopatológico, clasificación pTNM, grado nuclear de Furhman, creatinina antes y después de la cirugía, seguimiento oncológico. Análisis estadístico con programa SPSS v22.

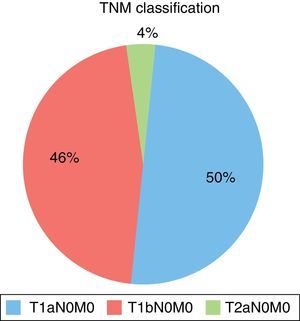

ResultadosSe incluyeron 28 pacientes, 14 hombres y 14 mujeres. Edad promedio 52.3 años, el abordaje fue lumbotomía en todos los pacientes. Promedio de 4.1 días de estancia intrahospitalaria. Promedio de sangrado transoperatorio de 380.3ml. La creatinina en promedio: antes de cirugía 0.96mg/dl, y después de 1.12mg/dl. Resultado de histopatología: 23 tumores de células claras, 2 angiomiolipomas, 2 oncocitomas y 1 quiste hemorrágico. 14 pacientes se presentaron en etapa T1aN0M0, 13 pacientes T1bN0M0, 1 paciente T2aN0M0.

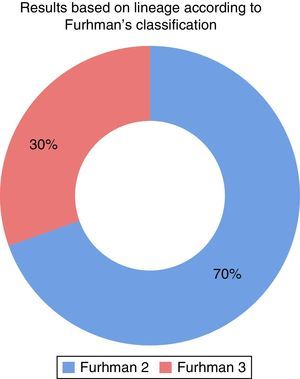

En los tumores de células claras, el grado nuclear Furhman 2 se presentó en 16 pacientes y Furhman 3 en 7.

ConclusiónLa cirugía preservadora de nefronas es el procedimiento de elección en pacientes con tumores renales pequeños, por buenos resultados funcionales (sin alteración significativa en la función renal), con adecuado control oncológico, con mínima incidencia de complicaciones.

Kidney tumours represent approximately 2–3% of all solid neoplasias. Each year 8.9 new cases every 100,000 are diagnosed and over 11,000 deaths are reported. Its incidence has increased from 2 to 4% due to the use of imaging techniques. It is more common in men by a 3:2 ratio; the mean age at the time of diagnosis is 65 years.1

As for renal cell carcinomas, it is believed that they mainly arise from proximal tubule cells, and this is probably correct for clear cell and variants of papillary ones. However, other histological subtypes of renal cell carcinomas, such as chromophobe and collecting duct ones, derive from more distal components of the nephron.2

Tobacco consumption is the most accepted risk factor for renal cell carcinoma, and causes between 20 and 30% kidney carcinoma cases in men and 10–20% in women; regardless of the type of exposure, it has been shown that the risk increases with the accumulated dose and the relative risk is directly linked to the length of time the patient has had this habit. Other risk factors in order of importance are: obesity, high blood pressure, and in a lower proportion, it is associated with urban and industrial settings and with exposure to industrial solvents (trichloroethylene), as well as with products from the footwear and fur industries, asbestos, cadmium, petroleum and gasoline. A family history of renal carcinoma is a non-modifiable risk factor (2–5%),2 mainly for multifocal or bilateral cases.

The probability of having mutations in geneVHL for sporadic tumours is 69%, and in another 20% there is hypermethylation of this gene. Von Hippel–Lindau syndrome is associated with a 50% incidence of renal cell carcinoma, and also to multiple and bilateral tumours by 80%.3

More than 30% of the kidney tumours are asymptomatic and are diagnosed during the end stage; in 50% of the cases diagnosis is incidental when performing abdominal imaging studies for another disease. In asymptomatic patients, the manifestations are variable and can be unspecific. It should be suspected in the presence of an abdominal tumour, a cervical adenopathy, a varicocele that does not decrease in size with conventional manoeuvres, bilateral oedema in lower limbs (sign of venous involvement). In cases with metastatic involvement there can be bone pain or persistent cough. 30% of the patients with symptomatic kidney cancer have paraneoplastic syndromes characterised by hypercalcaemia, high blood pressure, polycythaemia and Stauffer syndrome.

In the majority of cases, the diagnosis is established based on the results of a contrast CT scan. This is the standard method, since the unique strengthening of the tumour is seen because of the contrast material. The strengthening of renal masses is determined by comparing the values of the Hounsfield units obtained before and after administration of the contrast material. A magnetic resonance can provide additional data if the CT scan results are unspecific.4

To establish a diagnosis and be able to administer adequate treatment, it is essential to perform a fine-needle aspiration biopsy, which has 80–95% accuracy. Its most important indication is the differentiation between renal carcinoma and metastatic disease or renal lymphoma.4

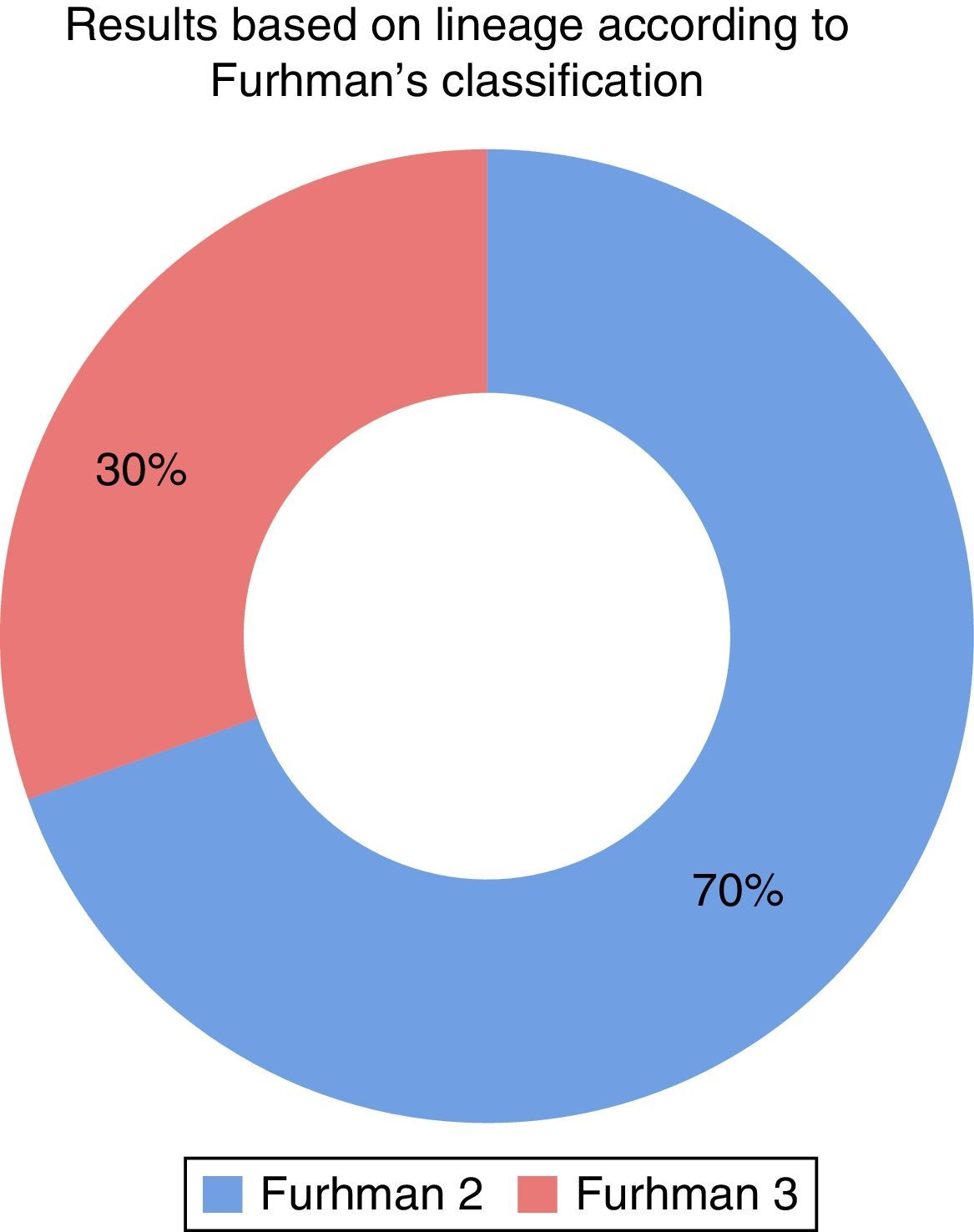

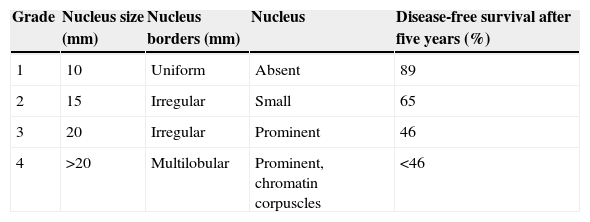

Fuhrman grade (Table 1) is one of the most important prognosis variables in all kidney cancer stages; it is a survival predictor that is independent from the pathological stage, which is only applied for the histological clear cell subtype. The most common Fuhrman's nuclear grades are 2 and 3. Grade 4 is present in 10% and grade 1 in less than 10%.5

A better understanding of the biology of the tumour, its staging patterns and the presentation pattern in patients with renal cell carcinoma allows a refined surgical approach, which restricts the long-term morbidity potential by maximising the preservation of the functional renal parenchyma.6

Nephron-sparing surgery has become an effective and safe alternative to radical nephrectomy and can be applied to candidate situations, such as renal disorders associated with genetic diseases, monorenal patients or patients with contralateral kidney disease.

Acceptable indications for nephron-sparing surgery can be divided into three categories, which include absolute, relative and elective indications. Absolutes: this must be taken into consideration in all patients with localised malignant tumours which, if not performed, would make the patient anephric, with subsequent and immediate need for renal replacement therapy. Relatives: contralateral kidney affected by a condition that can lower its function in the future (risk of developing contralateral kidney tumour, multiple tumours with bilateral affection). These relative indications for sparing surgery extend to patients with renal lithiasis disease, chronic pyelonephritis, urethral reflux, renal artery stenosis, high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus and other causes of glomerulopathy or nephrosclerosis. Electives: localised unilateral kidney tumours with healthy contralateral kidney.7

Nephron-sparing surgery has proven to be very effective for the treatment of small kidney tumours, since it decreases the risk of chronic renal disease in patients who have additional associated risk factors. The subsequent oncological check-up shows the same results as radical nephrectomy, for which complication rates are higher and there is a risk of renal failure. By having this alternative for this group of patients, therapeutic indication is reinforced with lower risks and more benefits in the renal residual preservation of the affected kidney, with long-term improvement of the prognosis.8

Material and methodsObservational, descriptive, retrospective and cross-sectional study for the period between January 1, 2010 and January 1, 2014. The experience with nephron-sparing surgery in patients with small kidney tumours (<7cm) at the Unidad Médica de Alta Especialidad, Puebla, from the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social (IMSS). Patients from the Urology service with kidney tumour diagnosis <7cm and who underwent nephron-sparing surgery, with full clinical records and full variables to be analysed were included.

The data extracted for every patient were: gender, age, symptomatology, comorbidities, surgical time, extension studies, intraoperative bleeding, histopathological report, Fuhrman's nuclear grade, tumour size and pre- and postoperative creatinine.

In the statistical analysis a descriptive statistic was used: averages, standard deviation and proportions. The results from the research were analysed using the SPSS v22. program.

Patients who underwent other types of surgery for kidney tumours <7cm or with incomplete clinical records were excluded.

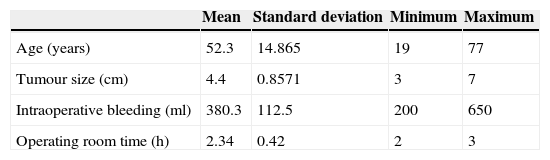

ResultsDuring the period of study, a total of 28 patients with a diagnosis of kidney tumour <7cm, who underwent nephron-sparing surgery at the National Centro General de Salud Manuel Ávila Camacho of IMSS in Puebla and who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were included: 50% were males (14) and 50% were females (14). The average age was 52.3 years, standard deviation was 14.8, and the range 19–77 years, with a maximum follow-up of three years (Table 2).

Regarding symptoms, four patients had macroscopic haematuria, 14 pain and ten patients were asymptomatic. Ten patients had a history of tobacco use. There was one monorenal patient due to left renal exclusion caused by renal lithiasis. Comorbidities were high blood pressure in ten patients (36%), diabetes mellitus in six (21%) and obesity in eight patients (29%).

The average operating theatre time was 2.3h with a standard deviation of 0.42 and a range between 2 and 3h. The average tumour size was of 4.4cm, with a standard deviation of 0.85 and a range between 3 and 7cm; 5cm tumours were more common in nine patients (Table 2).

Extension studies were negative in all patients. Surgical approach in 100% of the patients was by lumbotomy. The mean hospital stay was 4.1 days with a minimum of three and a maximum of six days. Average intraoperative bleeding was 380.3ml, with a standard deviation of 112.5 and a range between 200 and 650ml (Table 2).

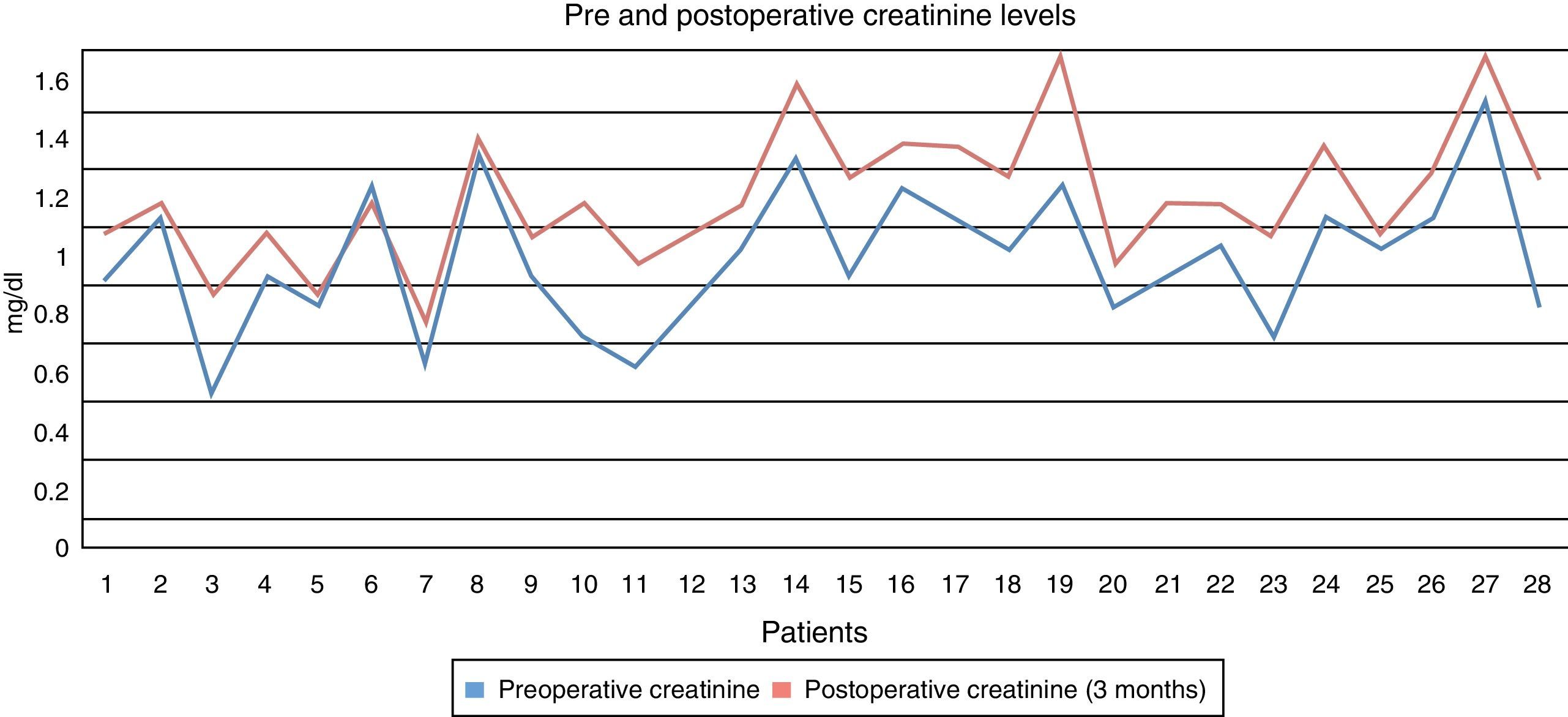

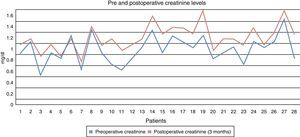

Creatinine levels were measured before surgery with an average of 0.96mg/dl: a minimum of 0.5mg/dl and a maximum of 1.6mg/dl. Creatinine levels were measured after surgery, obtaining an average of 1.12mg/dl, a minimum of 0.7mg/dl and a maximum of 1.6mg/dl (Fig. 1).

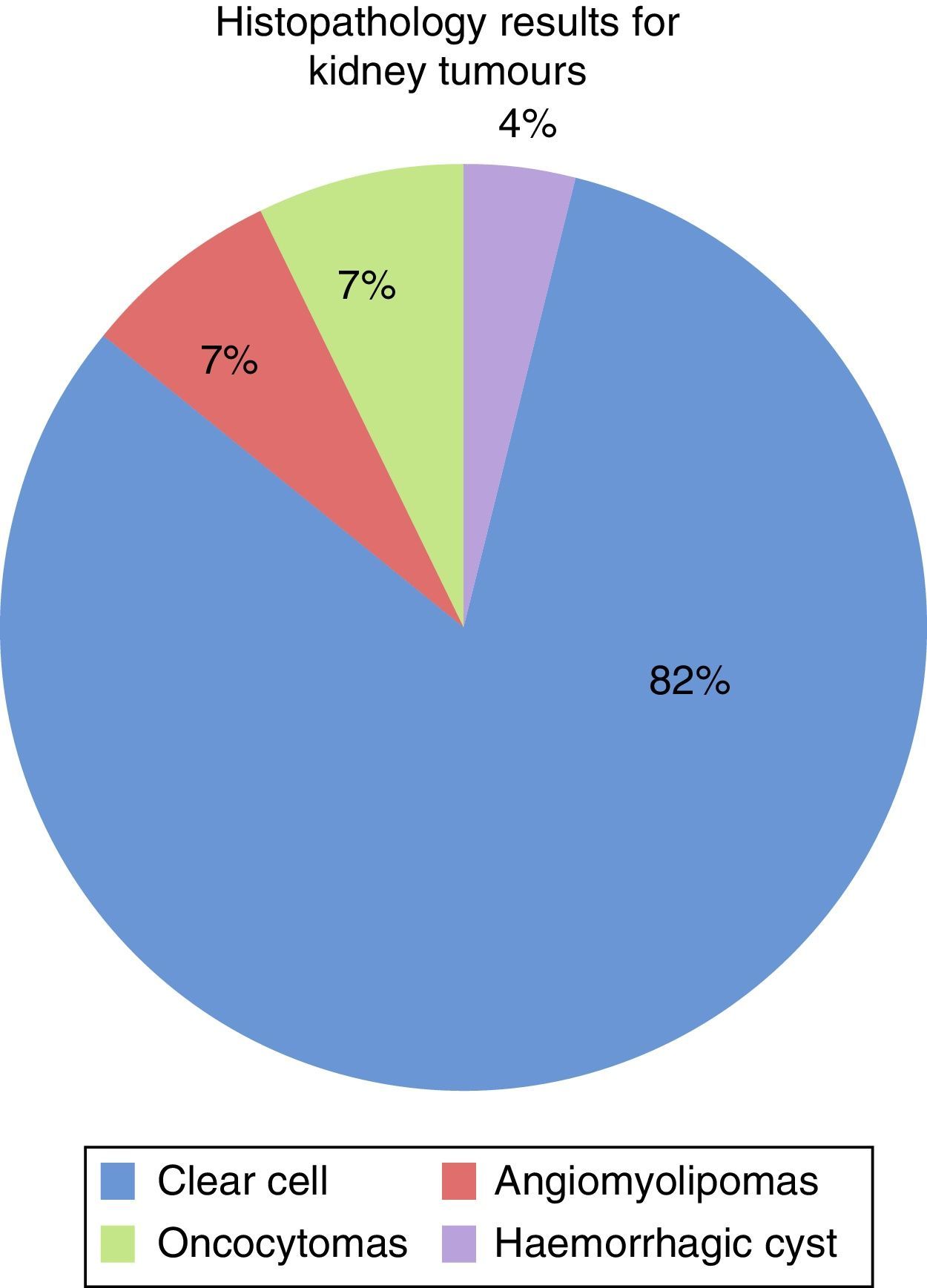

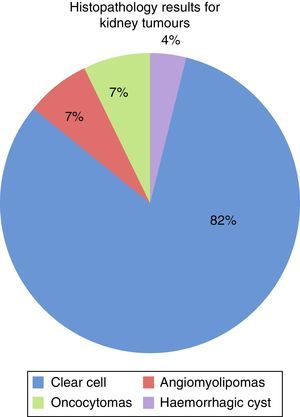

Histopathological results: 82% were clear cell tumours (23), 7% angiomyolipomas (2), 7% oncocytomas (2) and 4% haemorrhagic cysts (1). None of the patients had positive surgical borders (Fig. 2).

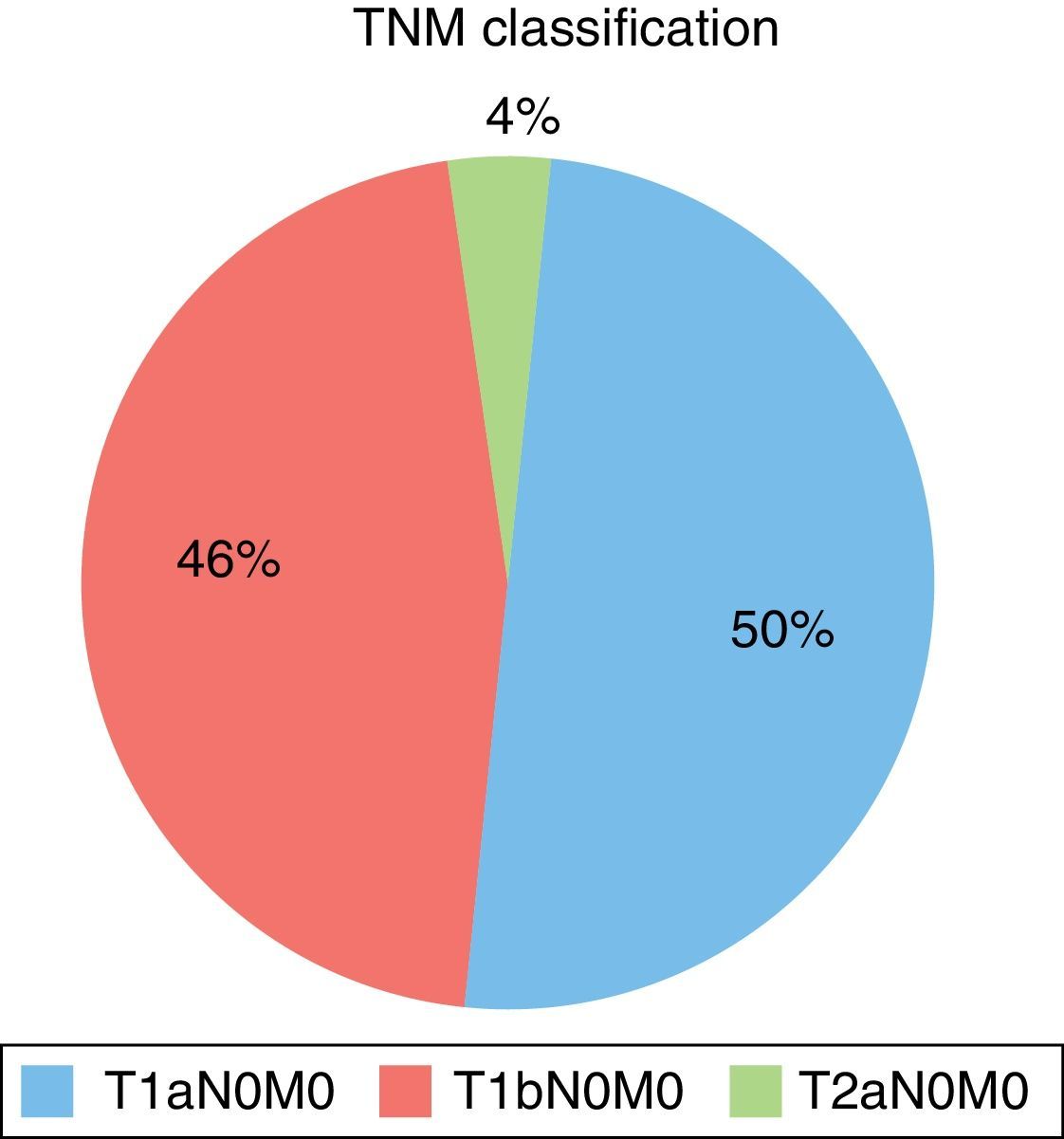

TNM classification found 14 T1a N0 M0 patients (50%), 13 T1b N0 M0 patients (46%), one T2a N0 M0 patient (4%) (Fig. 3). In patients with cell tumours, Fuhrman's nuclear grade 2 was most common for 16 patients (70%) and seven patients were Fuhrman's nuclear grade 3 (30%) (Fig. 4).

Radical nephrectomy was first described by Robson et al. in 1969,9 and it evolved quickly, acquiring improved surgical security. In 1987, Czerny10 proposed and performed a partial nephrectomy, which had excellent acceptance among urologists, since nowadays there are more sophisticated diagnosis imaging where the position of the tumour in relation to the different structures can be evidenced. It is also favoured with the use of more efficient methods to prevent renal ischaemic lesions. All patients who will undergo this type of surgical treatment must fulfil a previous protocol to dismiss a locally advanced disease or metastasis, as well as to define the association between the tumour and the intrarenal blood vessels and the collection system10.

In patients who are treated with partial nephrectomy, the aim is to preserve the greatest renal function possible with the best life prognosis. For this reason, the patient's age, creatinine levels before surgery and the volume of resected kidney should be taken into account.

Lopez et al.11 published the natural development story for chronic renal failure in patients who had radical nephrectomy in comparison with partial nephrectomy; assessing the results after three and five years, with a sample of 173 patients and 113 patients, respectively. They discovered a chronic renal failure-free rate of 89.5% after three years in patients who underwent radical nephrectomy, and a rate of 84.8% after five years. The rate was 100% after three and five years in patients who underwent partial nephrectomy.11 In our series of cases, we observed that out of 28 patients just one had a significant increase in creatinine levels and needed to be controlled by the nephrology service. None of the patients is doing renal function replacement therapy.

After surgical treatment, in patients with localised tumours, Garcia Galisteo et al.12 reported 20–30% recurrence or metastases. Lungs are the most commonly affected organs (50–60% of the cases). Metastasis usually occurs within the first three years after surgery. The disease-free interval between the diagnosis and the detection of the metastatic disease is associated with survival, in a way that patients whose disease-free interval is longer have a higher survival rate.

Up to this point in the study, all patients were doing a strict follow-up by having thoracoabdominal CT scans every four months during the first year and every six months afterwards, with no evidence of local recurrence or distant metastases.

The success rate of open partial nephrectomies ranges between 78% and 100%. One of the main disadvantages is the risk of local tumour recurrence, which affects 10% of the total of surgeries. It is possible that this recurrence is caused by multifocal and microscopic renal cell carcinoma. In a series of cases studies by D’Armiento et al.13 it was reported that the disease-free overall survival was of 98% in patients who made follow-up visits up to six years afterwards.

A limitation of our study was the follow-up period of up to three years, 100% of the patients were disease-free. However, this is a short-term follow-up so there are still no mortality or metastasis-free survival statistics.

Roos et al.14 established that nephron-sparing surgery reduced the risk of renal failure in comparison with radical nephrectomy. In our study, pre- and postoperative creatinine levels remained within normal ranges, with an average preoperative creatinine level of 0.96mg/dl, a minimum of 0.5 and a maximum of 1.6mg/dl; as well as an average postoperative creatinine level of 1.12mg/dl, with a minimum of 0.7 and a maximum of 1.6mg/dl, which corresponded with a monorenal patient, which can be justified and is similar to that established by worldwide medical bibliography.

ConclusionPartial nephrectomy is a safe oncological procedure in patients with small kidney tumours, with positive functional results and with no significant presence of alterations in renal functions. Also, its evolution is optimal and with minimal complications. Patients’ quality of life improves when they preserve renal functions.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Sánchez-Coral M, Báez-Reyes JR, García-Cano E, Quintero-León MÁ, Cárdenas-Rodríguez E, Priego-Niño A. Experiencia en cirugía preservadora de nefronas en pacientes con tumores renales pequeños. Cir Cir. 2015;83:297–302.