Collision tumours are extremely rare. They are defined by the presence of two tumours of different histological origin in the same organ.

Clinical caseA 71-year-old female with history of a carcinoid tumour removed 20 years ago without any recurrence. The patient was admitted with intestinal occlusion symptoms secondary to a right flank abdominal tumour. An exploratory laparotomy was performed, removing the tumour and applying optimal debulking.

The histopathological study reported bilateral ovary adenocarcinoma, as well as metastatic collision tumour of two histological types: well differentiated adenocarcinoma and a mixed malignant mesodermic Mullerian tumour.

The patient was treated with adjuvant chemotherapy with poor results (death in 24 months).

ConclusionsThe presence of collision tumours is extremely rare. There are no statistics or specific treatment reported. Diagnosis is made with histopathology. At the moment, no similar cases have been reported.

Los tumores de colisión son raros, se definen como la presencia de 2 tumores de diferente estirpe histológica en el mismo órgano o sitio.

Caso clínicoSe presenta el caso de una paciente femenina de 71 años, con antecedente de tumor carcinoide resecado hace 20 años, sin recidiva. La paciente presenta cuadro de oclusión intestinal secundario a tumor en flanco derecho del abdomen. Se le realiza laparotomía exploradora con resección del tumor, y citorreducción óptima. En el estudio histopatológico se encuentra adenocarcinoma de ovario bilateral, así como tumor de colisión en metástasis, el cual presenta 2 estirpes histológicas: adenocarcinoma bien diferenciado y tumor mixto maligno mülleriano mesodérmico. La paciente es enviada para quimioterapia adyuvante, presentando mala evolución. Murió a los 24 meses.

ConclusionesLa presencia de tumores de colisión es extremadamente rara, en la literatura no hay estadísticas ni tratamiento específico. Su diagnóstico es histopatológico. No se ha reportado ningún caso similar en la literatura médica.

Collision tumours are highly rare neoplasias; there are few series and case reports on them in the English literature. The presence of several primary neoplasias in the same individual is a frequent occurrence; they can be synchronous (within a 6-month interval) or metachronous (within an interval longer than 6 months). However, the presence of two histological lineages in the same organ or place is called a collision tumour. Histologically, both populations collide without there being transition areas between them. They have been described as occurring in several places: the cardia, cervix, bladder, liver, lung, thyroids and biliary ducts. Most of them are carcinomas and sarcomas collisions or lymphomas collisions, and more infrequently, carcinomas collisions.1 There are several theories, such as the simultaneous proliferation of two different cell lines, a common origin from a pluripotent precursor cell that would differentiate into two components, or the casual development of two non-related tumours. Genetic predisposition, old age, exposure to environmental carcinogens, previous treatments with radiotherapy or chemotherapy and immunosuppression, among others, are all factors that increase the risk of developing these tumours.

The purpose of this study is to show the first case of a collision tumour in a metastasis in Mexico, and possibly the first case report in the English language medical literature.

Clinical caseThe case is a 71-year-old patient who has a history of intestinal surgery due to a carcinoid tumour in her small intestine more than 20 years ago; she denies having additional medical history of relevance.

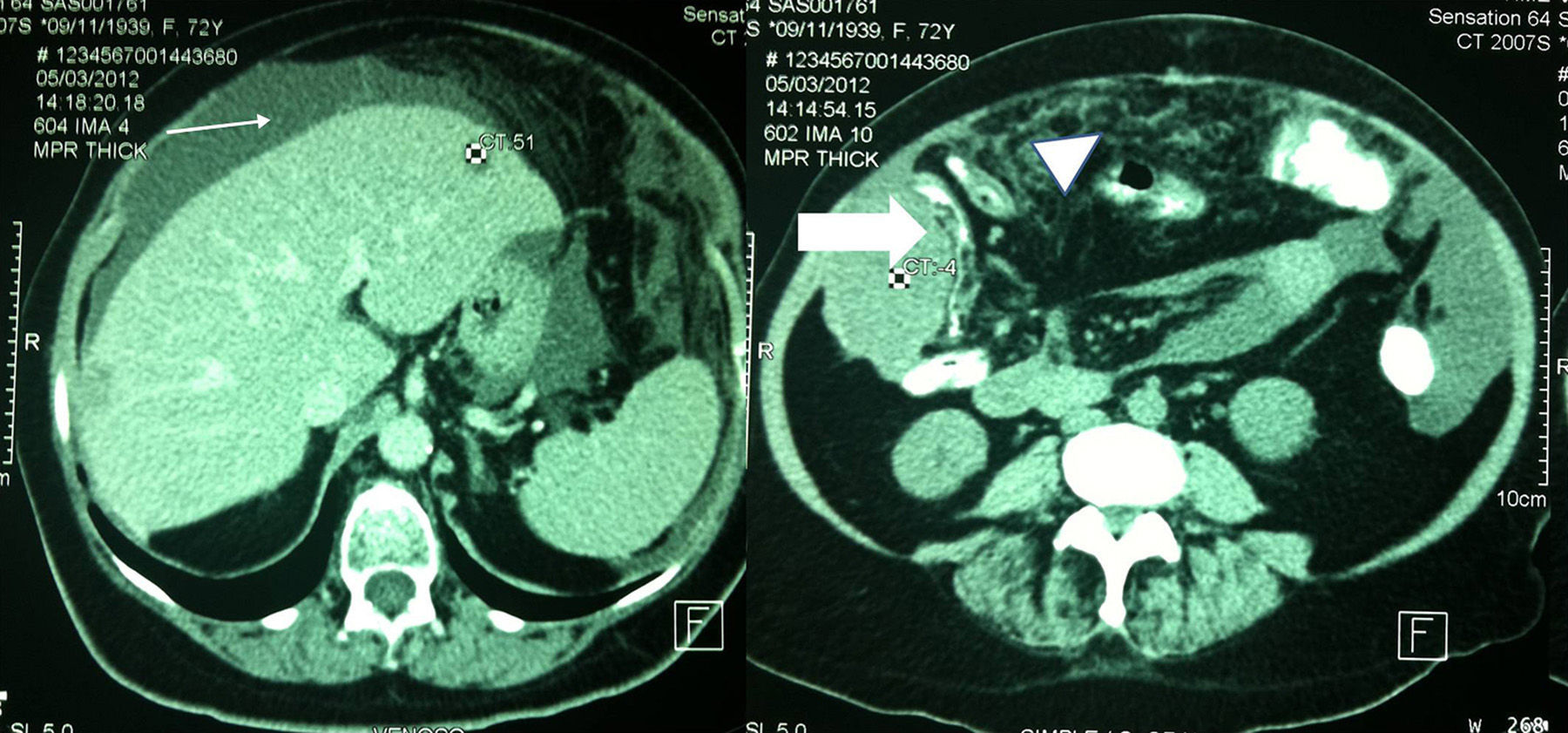

She was admitted in February 2012, with symptoms of intermittent partial bowel obstruction, with significant abdominal bloating, constipation, nausea and vomiting, and volume augmentation in right flank, non-mobile. An abdominal ultrasound was performed, which only showed an anechoic lesion in the left lobe of her liver. The abdominal computerised axial tomography showed the presence of free fluid, a hepatic cyst that had already been detected by the sonography, and a tumour that compressed the colon in her right flank; all these data are an indication of carcinomatosis (Fig. 1). Laboratory data were within normal ranges.

The patient did not show any improvement from the obstruction symptoms despite medical treatment, so an exploratory laparotomy was performed, through which 3 l serohaematic ascites, omental, mesentery and pelvic viscera implantations were found, with no evidence of primary; a 12cm×8cm tumour was seen in the right parietocolic gutter with encephaloid aspect, papillary, with good cleavage plane, which could be removed. Cytoreductive surgery was performed, which included Piver 1 total hysterectomy and a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with optimum removal (R0).

Patient was taken to the surgical inpatient unit; she showed good progress. She was discharged in 72h, with adequately tolerated oral route. She was sent to Medical Oncology for adjuvancy in March, 2012. Treatment with carboplatin and paclitaxel was initiated. The patient was asymptomatic at her one-year follow-up. However, disease recurrence occurred at month 18, with ascites, abdominal pain, weight loss and symptoms of partial bowel obstruction. Patient decided not to continue with any treatment and died 24 months after the diagnosis.

Histopathology. There is a neoplastic lesion that corresponds to a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma on the surface of both ovaries. It forms a solid nodule in the right ovary and in the left ovary, over its serosa, and there are many Psammoma bodies. There is metastasis in the omental and in the abdominal wall, in which there is a lesion formed by papillary structures of very variable size with two types of differentiation; one of them is epithelial and covers the surface of the papillary areas, the epithelium is stratified in many places and it has cells with hyperchromatic and somewhat pleomorphic nuclei with frequent mitotic figures and non-vacuolated eosinophilic cytoplasm. The second component corresponds to a sarcomatosis, with a compact arrangement of cells, scarce cytoplasm with ill-defined borders and occasionally with uninucleate or multinucleate giant cells. There are areas of desmoplastic fibrous stroma and of aponeurotic tissue from the abdominal wall.

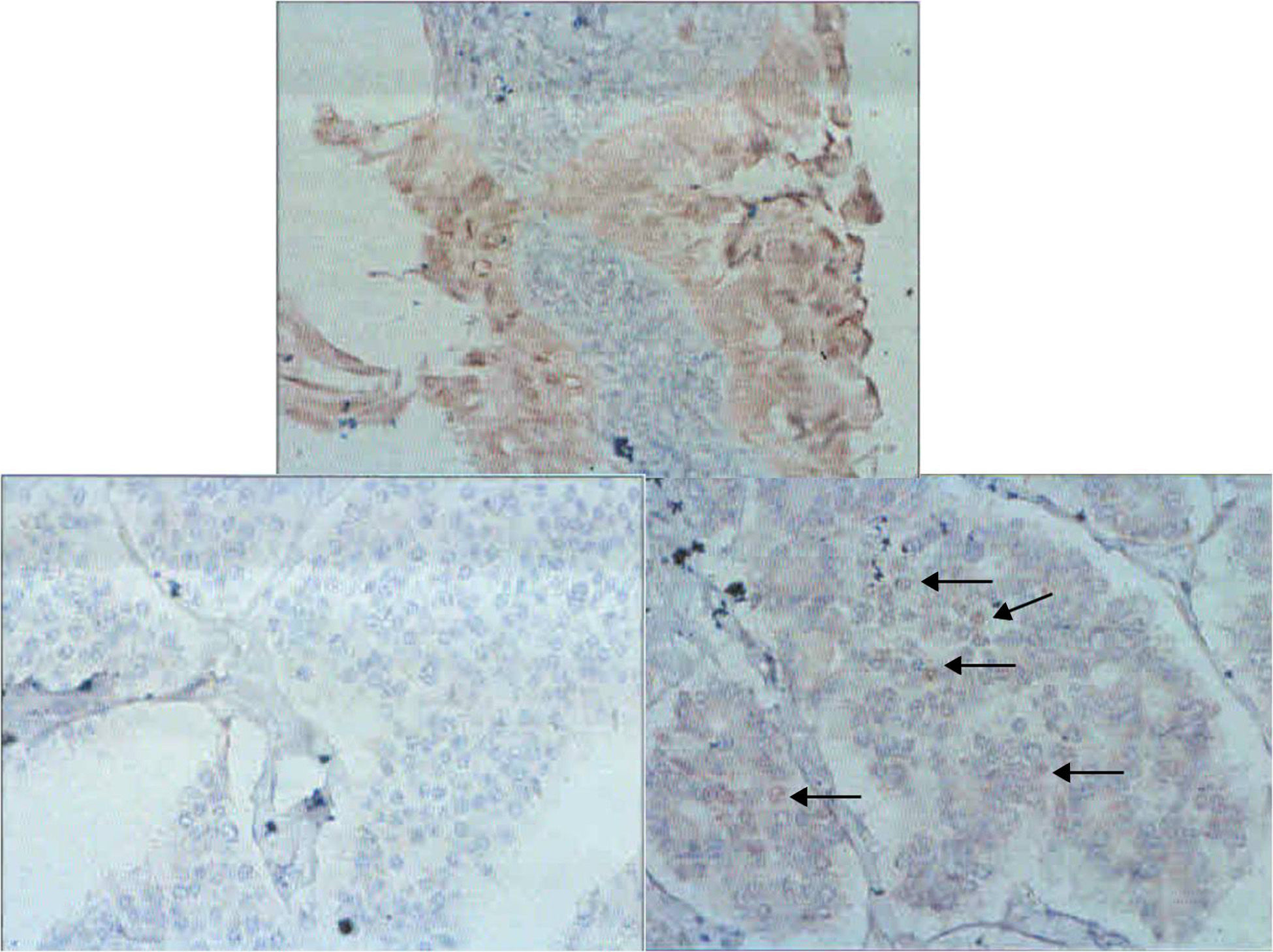

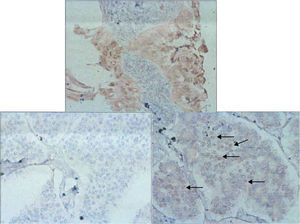

The immunohistochemistry analysis shows p53 and WT1 markers that are positive in both components; p16 is only positive in the sarcomatous component. The endometrial origin rests on the CD10, CA-125 and oestrogen receptor positivity. The sarcomatous component is desmin and S-100 positive, and WT1, p16 and CD10 negative.2,3 Oestrogen receptors in the well-differentiated adenocarcinoma part were negative, and in the malignant mixed mesodermal (müllerian) tumour, that were positive (Fig. 2). The ovaries presented a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma.

We came to a diagnosis of collision tumour in the abdominal wall metastasis, which was formed by a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma component and a malignant mixed mesodermal (müllerian) tumour component.

DiscussionThe physical examination, the findings in imaging and research studies do not confirm the existence of collision tumours, the latest being histopathological incidents.4 There have been few reports about collision tumours in Mexico, with only some skin cases.5–7

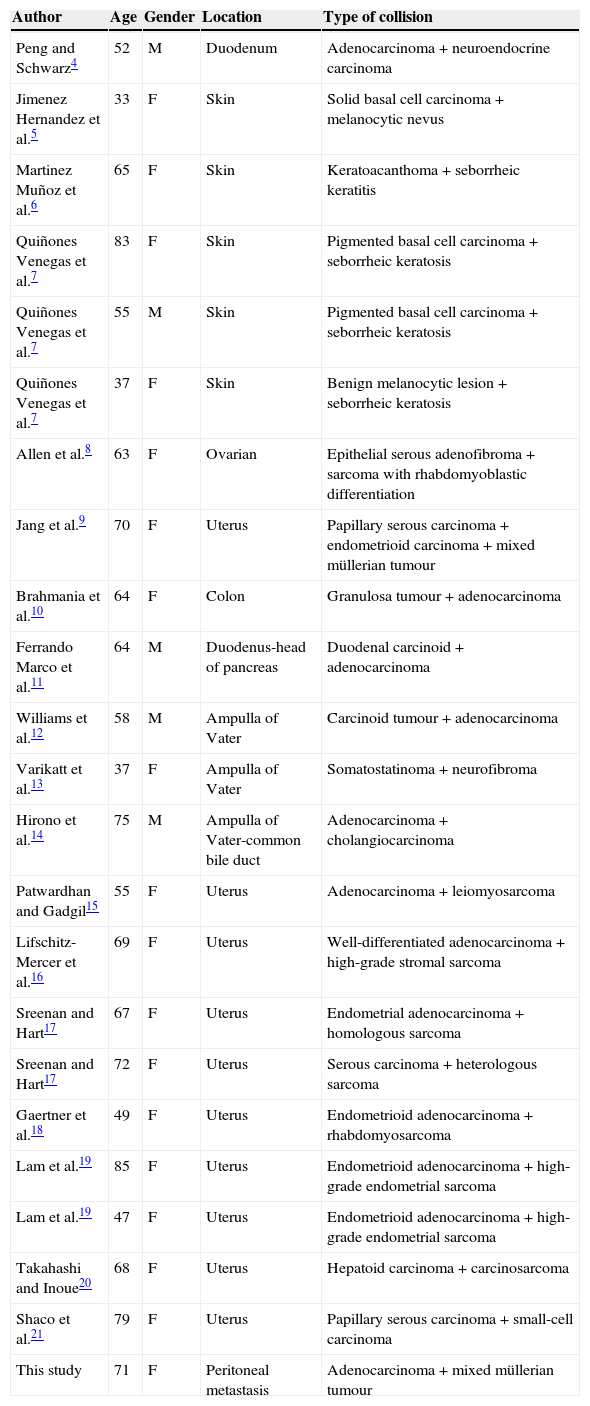

The combination of a carcinoma and a mixed mesodermal tumour is infrequent.8 Until now, there has been no report in medical literature of a case similar to the one presented. Most of the collision tumours are described under gynaecological disorders. Table 1 shows some collision tumours with their histological location and lineage.

Reported collision tumours.

| Author | Age | Gender | Location | Type of collision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peng and Schwarz4 | 52 | M | Duodenum | Adenocarcinoma+neuroendocrine carcinoma |

| Jimenez Hernandez et al.5 | 33 | F | Skin | Solid basal cell carcinoma+melanocytic nevus |

| Martinez Muñoz et al.6 | 65 | F | Skin | Keratoacanthoma+seborrheic keratitis |

| Quiñones Venegas et al.7 | 83 | F | Skin | Pigmented basal cell carcinoma+seborrheic keratosis |

| Quiñones Venegas et al.7 | 55 | M | Skin | Pigmented basal cell carcinoma+seborrheic keratosis |

| Quiñones Venegas et al.7 | 37 | F | Skin | Benign melanocytic lesion+seborrheic keratosis |

| Allen et al.8 | 63 | F | Ovarian | Epithelial serous adenofibroma+sarcoma with rhabdomyoblastic differentiation |

| Jang et al.9 | 70 | F | Uterus | Papillary serous carcinoma+endometrioid carcinoma+mixed müllerian tumour |

| Brahmania et al.10 | 64 | F | Colon | Granulosa tumour+adenocarcinoma |

| Ferrando Marco et al.11 | 64 | M | Duodenus-head of pancreas | Duodenal carcinoid+adenocarcinoma |

| Williams et al.12 | 58 | M | Ampulla of Vater | Carcinoid tumour+adenocarcinoma |

| Varikatt et al.13 | 37 | F | Ampulla of Vater | Somatostatinoma+neurofibroma |

| Hirono et al.14 | 75 | M | Ampulla of Vater-common bile duct | Adenocarcinoma+cholangiocarcinoma |

| Patwardhan and Gadgil15 | 55 | F | Uterus | Adenocarcinoma+leiomyosarcoma |

| Lifschitz-Mercer et al.16 | 69 | F | Uterus | Well-differentiated adenocarcinoma+high-grade stromal sarcoma |

| Sreenan and Hart17 | 67 | F | Uterus | Endometrial adenocarcinoma+homologous sarcoma |

| Sreenan and Hart17 | 72 | F | Uterus | Serous carcinoma+heterologous sarcoma |

| Gaertner et al.18 | 49 | F | Uterus | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma+rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Lam et al.19 | 85 | F | Uterus | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma+high-grade endometrial sarcoma |

| Lam et al.19 | 47 | F | Uterus | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma+high-grade endometrial sarcoma |

| Takahashi and Inoue20 | 68 | F | Uterus | Hepatoid carcinoma+carcinosarcoma |

| Shaco et al.21 | 79 | F | Uterus | Papillary serous carcinoma+small-cell carcinoma |

| This study | 71 | F | Peritoneal metastasis | Adenocarcinoma+mixed müllerian tumour |

F: female; M: male.

The combination of tumours in one organ or place can be divided into two clinical-pathological groups: collision tumour or compound tumour. In the first one, the histologically different tissues juxtapose with healthy stroma between them. In the compound tumour, the different components intermingle to form one tumour mass.9

Some theories about collision tumours regard them as a proliferation of two different cell lines, or as having a common origin in a totipotential cell, which differentiates into two different cell lines.10 A third theory involves the sarcomatous conversion of an epithelial tumour. Lastly, it is important to differentiate it from a tumour that metastasises in another one. Mixed müllerian tumours are aggressive neoplasias; extragonadal presence is infrequent. In a case presentation, Kurshumliu et al.3 refer to only 30 published cases in medical literature, the majority of which involved postmenopausal women. A theory proposed by the same authors is that the origin is in an endometriotic area.

The origin of this tumour can probably be explained as an ovarian primary tumour metastasis (adenocarcinoma component) and the sarcomatous degeneration of some endometriotic area in the wall; both tumours collided in the same neoplasia.

In general, mixed tumours have a bad prognosis and a postoperative survival of 14 months, although in our case the survival was of 24 months (12 months free of tumour).

Treatment for these tumours is performed by implementing a combination of therapies, treating each tumour as if it were the only one. This case was treated with surgery to solve the obstruction symptoms, and then it was decided to initiate chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel (since it is a useful method in epithelial ovarian tumours, as well as in uterine sarcomas).

ConclusionCollision tumours are infrequent neoplasias; there are few reports about them in medical literature. Their prognosis is unknown, since there are no previous similar cases. It is possible that long-term survival is similar to that for mixed peritoneal müllerian tumours.

The treatment adapted to this case was surgery with optimal cytoreduction, as well as adjuvancy.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Rosas-Guerra OZ, Pérez-Castro y Vázquez JA, Andrade-López GH, Vera-Rodríguez F, Garza-de la Llave H. Tumor metastásico de colisión. Informe de un caso. Cir Cir. 2015;83:238–42.