The gastrointestinal tract lipomas are a rare, benign, slow-growth condition and can be a diagnostic challenge, they are more frequent in the colon. The gastric lipoma occurs in fewer than 5% of cases, and represents less than 1% of all gastric tumours, usually their finding is incidental and the initial presentation may be obstruction, bleeding and intussusception. The purpose of presenting this case is for its rarity, the few symptoms that the patient presented and to collect the most current information about the diagnosis and treatment.

Clinical caseWe report the case of a 59-year-old male patient who after having suffered acute pancreatitis a tomography control was made looking for complications it found a pylorus-duodenal intussusception, an endoscopy was performed and a tumour about 6cm was found and biopsies without confirm diagnosis, so it was decided to perform a partial gastrectomy, histopathology study confirmed the diagnosis of gastric lipoma as well as disease free margins. He was maintained with adequate postoperative evolution currently asymptomatic.

ConclusionsThe gastric lipoma is a rare benign entity that can mimic a malignancy, in our case an incidental finding which was managed by partial gastrectomy with satisfactory postoperative results.

Los lipomas del tracto gastrointestinal son una condición rara, benigna y de crecimiento lento que puede constituir un desafío diagnóstico, son más frecuentes en el colon. El lipoma gástrico se presenta en menos del 5% de los casos y representa menos del 1% de todos los tumores gástricos, por lo general su hallazgo es incidental y su presentación inicial puede ser: obstrucción, hemorragia e invaginación. El objetivo de presentar este caso es por su rareza, los pocos síntomas que presentó el paciente y recopilar la información más actual sobre su diagnóstico y tratamiento.

Caso clínicoPaciente masculino de 59 años para el cual tras haber padecido un cuadro de pancreatitis aguda, se solicitó control tomográfico para buscar complicaciones y se encontró una invaginación píloro-duodenal, se le realiza una endoscopia en la que se identifica un tumor de 6cm, a pesar de que se toma una biopsia no es posible confirmar un diagnóstico, por lo que se decide realizar una gastrectomía parcial, y el estudio de histopatología confirmó el diagnóstico de lipoma gástrico así como márgenes libres de enfermedad. Se mantuvo con adecuada evolución posquirúrgica y actualmente asintomático después de 18 meses de seguimiento.

ConclusionesEl lipoma gástrico es una entidad benigna rara que puede simular una enfermedad maligna, en nuestro caso, un hallazgo incidental el cual se manejó mediante una gastrectomía parcial con resultados posquirúrgicos satisfactorios.

According to Neto et al.,1 gastrointestinal lipomas are a rare disease with very few symptoms. They were first described in 1842 by Jean Cruveilhier at the University of Paris. Gastrointestinal lipomas are more frequently found in the colon (60–75%) and small intestine (more than 31.2%)1; the gastric lipoma accounts for less than 5% of tumours present in the gastrointestinal tract and less than 1% of benign tumours present in the stomach.1

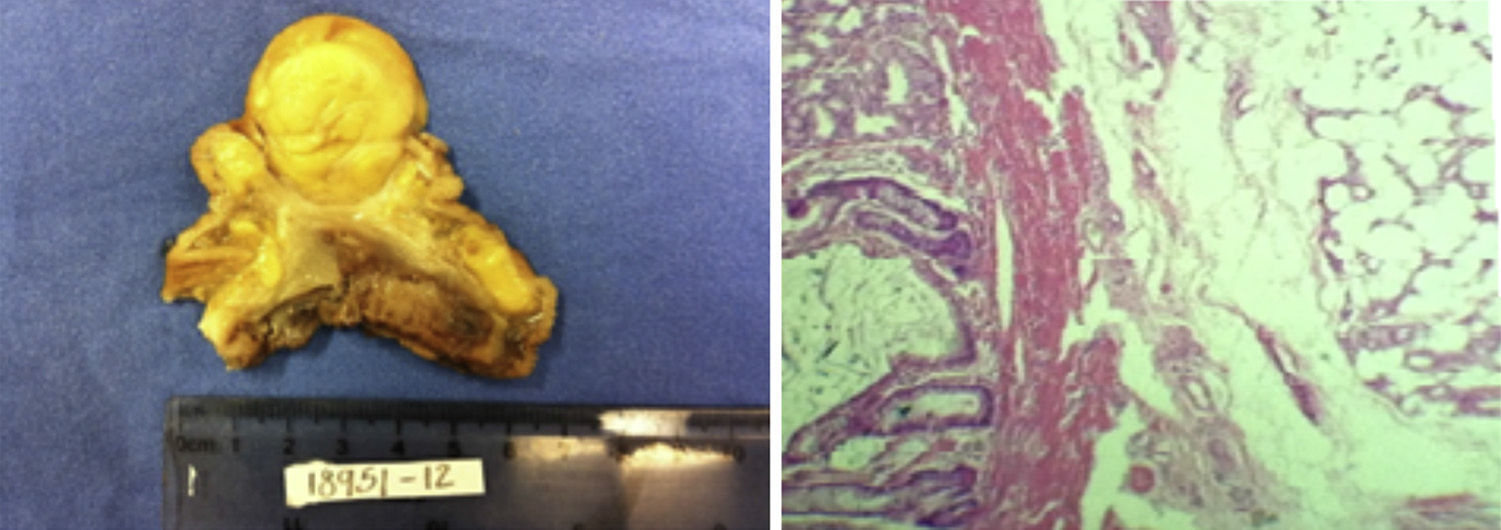

On a global level, there are approximately 220 reports about this pathology.2 In general, gastric lipomas are slow-growing lesions, and about 90–95% of the cases are submucosal lipomas, while 5–10% constitutes serosal lipomas. The aetiology of the lipoma is still unknown. However, it is believed that it may be an acquired condition or a condition secondary to an embryological modification. Most of these tumours are small and asymptomatic, and are accidently identified while conducting an autopsy.2 Histologically, these tumours are made up of well-differentiated adipocytes with a fibrous capsule in which yellow tissue may be found if sectioned.3 Gastric lipomas are more frequently found in the antrum in 75% of the cases. However, they may be found in any part of the stomach.

Gastric lipomas frequently go unnoticed or are confused with other types of more frequent tumours, such as gastrointestinal stromal tumours, leiomyoma, fibroma, neurilenoma, adenomyoma, Brunner gland adenoma and heterotopic pancreas.

The gastric lipoma is a benign entity, but it may simulate a malignant behaviour.4 When tumours have a size of 3–4cm, the most frequent clinical symptom is bleeding in the upper digestive tract, which may be acute or chronic and results from the ulceration of the mucosa producing the tumour.4

Abdominal pain and obstructive symptoms are common at its onset, and this is more frequent if the tumour has an endoluminal growth that may worsen with intussusception, which is not rare, and may result in lesions located in the prepyloric region and prolapse towards the duodenal bulb.4 Generally, during an endoscopy, gastric lipomas appear as smooth tumours, oval or round, well-defined lesions, which are compressible and, on conduction of barium studies, present little attenuation.4

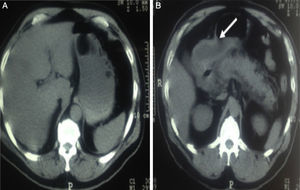

It has been demonstrated that the tomography is considerably important for the diagnosis of gastric lipomas. In general, these lesions are well circumscribed, uniform, with fatty density and attenuation ranging from −70 to −120HU. These characteristics allow for a diagnosis by a tomography, without having to conduct an endoscopy or even surgery if the patient presents no symptoms.5,6

The surgical treatment may be laparoscopic in tumours smaller than 6cm, while subtotal gastrectomy is recommended in tumours larger than 6cm.7

Clinical caseA 59-year-old male patient, with a history of marijuana consumption on a single occasion, alcoholism and smoking since he was 28 years old, 8-year progression high blood pressure controlled with enalapril, dyslipidaemia treated with pravastatin and benzafibrate, renal lithiasis with stone expulsion in 2 occasions, the last of which occurred in 2011, and mild acute pancreatitis of alcoholic origin.

The condition began after he was discharged from hospital, to which he had been admitted due to symptoms of acute pancreatitis. He was seen in a gastroenterology outpatient setting and an abdominal tomography was ordered to determine the presence of late complications. The tomography revealed a probable invagination of the pylorus and duodenum, increase in the fat density of the pancreas, with subsequent reinforcement using hypodense nodule images with greater reinforcement at the level of the parenchyma (Fig. 1). An endoscopy was ordered, which revealed a thinned, erythematous and thickened gastric mucosa with reticular pattern, an antrum rotated on its own longitudinal axis, which made it impossible to access this segment after air insufflation; the pylorus was enlarged and open and did not fully close with peristalsis. In the minor curve, there was a pedicled polypoid tumour with a smooth surface of 8cm in diameter. A biopsy sample was collected, and the presence of gastritis and gastric tumour was determined. The histopathological result was positive for malignancy due to incomplete intestinal metaplasia in the antrum.

Based on the result of the pathological anatomy, a second endoscopy was ordered, and new biopsy samples were collected. This revealed, on the major curve towards the rear part, a large pedicled polyp, with a wide base of approximately 6cm and infiltrative aspect of the mucosa, regular surface, reddish colour, ulceration on the base and some apex segments, and very hard consistency. Several biopsy samples were obtained from the base. On retroflexion, a polypoid growth with fibrin-covered ulcerations was observed, which confirmed the diagnosis of gastric polyp. The pathological anatomy report included moderate to severe chronic gastritis, with moderate focally eroded atrophy, ulcerated, full intestinal metaplasia with low-grade dypslasia areas (mild), associated with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)++/+++, polyp biopsies negative for malignancy.

Based on the tumour characteristics, an endoscopic ultrasound was ordered, which revealed a lesion in the gastric antrum, of 49mm×56mm in diameter, dependent on the muscular layer, with serous infiltration in some areas, without metastasis or adenopathies.

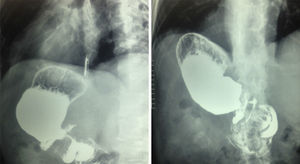

A management technique was implemented for the eradication of H. pylori based on the report of intestinal metaplasia, and the patient was referred to the general surgery department for the definite management of the lesion. The report in connection with the control oesophagogastroduodenal series was: loss of antrum and pylorus morphology with considerable filling defect, with anomalous confluence in the folds of the gastric antrum, suggestive of narrowness at this level.

Presurgical lab results were as follows: haemoglobin 9.3g/dl, haematocrit 32.5%, leukocytes 6.5 thousand/mcl, platelets 388 thousand/mcl, neutrophils 52.9%, prothrombin time 11.1 seconds, international normalised ratio (INR) 0.92, partial thromboplastin time (PTT) 34.4, glucose 99mg/dl, creatinine 0.8mg/dl, cholesterol 124mg/dl, triglycerides 71mg/dl, albumin 3.5g/dl, lactic dehydrogenase 258IU/l.

It was decided to schedule a surgical intervention, which revealed the presence of a gastric antrum tumour located in the front wall, with intraluminal growth of approximately 5cm×5cm, without evidence of adenopathies and with no alterations on a macroscopic level in the rest of the cavity. It was decided to conduct a partial gastrectomy with antrectomy, gastrojejunal anastomosis and Roux-Y jejuno-jejunal anastomosis.

There was adequate post-surgical progression, without leakage evidence. As there was oral tolerance 4 days after surgery in a progressive manner, without complications, the patient was discharged.

The histopathology result showed a gastric lipoma of 5cm, and the borders of the surgical piece were negative for malignancy (Fig. 2).

The patient was seen 2 weeks after the outpatient appointment. He was in good conditions, with oral tolerance, and had a post-surgical oesophagogastroduodenal series without alterations (Fig. 3).

There was adequate post-surgical progression, and the patient presented no symptoms after 18 months of follow-up.

DiscussionGastric lipomas are very rare. Most gastrointestinal tract lipomas are located in the colon and 5% are located in the stomach. The onset age ranges from the fifties to the sixties, and there is no predominant gender.1 Its aetiology is still unknown, but some theories suggest that there is embryological sequestration of adipocytes or an ageing process.1

These are benign tumours of mesenchymal nature, made up of soft tissue consisting of mature lipocytes circumscribed by a fibrous capsule. From a macroscopic point of view, lipomas are made up of a fatty yellowish tissue of different sizes.1,2

Most of them are small asymptomatic lesions accidentally detected in routine or follow-up studies performed as a result of another pathology or even during autopsies.3

More than 90% of the cases occur in the submucosa and they are more frequently located in the pyloric antrum.3 This location explains the high frequency of intussusception occurring within the pylorus or duodenum, which results in symptoms of dyspepsia and/or obstructive symptoms.3,4

The symptoms are related to the size of lesions. When lesions are smaller than 2cm, they are usually asymptomatic and accidentally discovered. In tumours larger than 3–4cm, the most frequent clinical symptoms are bleeding in the upper digestive tract, whether acute or chronic,3 caused by the ulceration of the tumour, as well as abdominal pain and obstruction data, especially if there is endoluminal growth that may cause intussusception.4 The most relevant aspect about large lesions is the probability of prolapse, which may produce venous stasis with subsequent formation of ulcers, so resulting in an actual surgical emergency.1–3,5

The most important differential diagnosis of the gastric lipoma is the liposarcoma, which is a soft tissue tumour of the gastrointestinal tract, such as the leiomyoma or fibroma, as well as other intramural tumours, such as neurilenoma, adenomyoma, Brunner gland adenoma and ectopic pancreas.1,4

Classic radiological findings of the gastric lipoma are a smooth tumour, with well-defined borders, oval or round shape and compressible during the fluoroscopic exam, which presents attenuation in barium studies.5,6

The tomography is very useful for its diagnosis. It appears as a well-defined tumour, of fatty density, with attenuation ranging from −70 to −120HU, which is pathognomonic in these cases. Thus, in most cases, the tomography may produce a diagnosis without having to perform an endoscopy.5,6

The magnetic resonance imaging has an excellent sensitivity for fat and may be used in some populations, such as children or patients with an allergy to contrast material.5,6

In the endoscopy, some lesions are translucid enough to allow for a correct diagnosis. Sometimes, this produces a “bull's-eye” ulceration, which makes it impossible to distinguish these lesions from other submucosal tumours.5,6

In the endoscopy, there are 3 classic signs of lipoma: the “tent” sign is the presence of gastric folds towards a tumour ulcer; the “pillow” sign is the feeling of pressing a sponge; and lastly, the presence of yellowish mucosa.5,6

If a submucosal lesion larger than 2cm or an oesophagogastroduodenal series is detected in an endoscopy, a tomography must be performed to obtain data suggesting a lipoma. If there are data suggestive of a lipoma, it is not necessary to conduct a biopsy. This procedure is only indicated when lesions are not fully fatty. If a biopsy sample is collected during an endoscopy, this will not produce a diagnosis, since the lesion is submucosal with normal mucosa over it.7

Accidentally discovered or asymptomatic lipomas must not be treated, since there is no report on malignant degeneration.1,7

The laparoscopic resection is reserved for tumours smaller than 6cm or with endoluminal or extraluminal protrusion. The indications for surgical resection are symptoms jeopardising the patient's life and the impossibility of ruling out malignancy.1 Moreover, a subtotal gastrectomy is generally indicated for tumours larger than 6cm.8–10

ConclusionsThis article presented the case of a 59-year old male patient, with histopathological diagnosis of gastric lipoma, located in the antrum and front wall, which was asymptomatic and accidentally discovered after tomographic controls performed due to a previous diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Nevertheless, a study protocol was implemented, which led to the suspicion of malignancy upon conducting endoscopic biopsies. Thus, it was decided to provide surgical treatment by performing a partial gastrectomy with antrectomy, gastrojejunal anastomosis and Roux-Y jejuno-jejunal anastomosis. The histopathological report was gastric lipoma of approximately 5cm, and the borders of the surgical piece were negative for malignancy. Currently, the patient is subject to a 6-month follow-up, presents no symptoms of the disease or recurrence, according to the tomographic and endoscopic control.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: López-Zamudio J, Leonher-Ruezga KL, Ramírez-González LR, Razo Jiménez G, González-Ojeda A, Fuentes-Orozco C. Lipoma gástrico pediculado. Reporte de caso. Cir Cir. 2015;83:222–6.