Primary posterior perineal hernias in men are rare. We report a case of this type of hernia associated with dolichocolon, a condition which, to our knowledge, has not been reported previously.

Clinical caseA 71-year old male presenting with a perineal tumour of 40 years evolution. He had no history of perineal surgery or trauma. On physical examination, a lump of 4cm×3cm was observed in the right para-anal region, which increased in volume during the Valsalva manoeuvre. Computed tomography showed a defect in the pelvic floor, which was reconstructed using a roll of polypropylene mesh in the hernia defect.

DiscussionThe case described is of interest, not only because a perineal hernia is a rare clinical entity, but also because repair using a roll of mesh has not been reported associated with a dolichocolon, which can be considered a factor risk for development.

ConclusionsThe surgical approach and repair technique of the pelvic floor for perineal hernias should be individualised. The use of mesh for reconstruction should always be considered. The presence of dolichocolon can contribute to the gradual development of a perineal hernia.

Las hernias perineales posteriores primarias en hombres son muy raras. Presentamos un caso de este tipo de hernia asociada a dolicocolon, una condición que a nuestro conocimiento no ha sido antes reportada.

Caso clínicoUn hombre de 71 años de edad presentó una tumoración perineal de 40 años de evolución. No tuvo el antecedente de cirugía perineal ni de trauma. En la exploración física se apreció una protuberancia de 4×3 cm en la región paraanal derecha, que aumentaba de volumen durante la maniobra de Valsalva. La tomografía computada mostró un defecto en el piso pélvico. Para su reconstrucción se colocó un rollo de malla de polipropileno dentro del defecto herniario.

DiscusiónEl caso que describimos es relevante por tratarse de una entidad clínica rara, como lo es la hernia perineal; pero, además, no se ha descrito su reparación mediante un rollo de malla ni se ha reportado asociada a dolicocolon, el cual puede ser considerado un factor de riesgo para su desarrollo.

ConclusionesEl abordaje quirúrgico y la técnica de reparación del piso pélvico de las hernias perineales deberán individualizarse. El uso de malla para la reconstrucción deberá siempre ser considerada. La presencia de dolicocolon puede contribuir al desarrollo progresivo de una hernia perineal.

Pelvic floor hernias are rare. Three varieties may be distinguished in decreasing order of frequency: obturator muscle hernias, perineal hernias and sciatic hernias.1 Perineal hernias are defined as protrusions of intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal content caused by a defect in the pelvic diaphragm.2 They are anatomically classified as: anterior or posterior based on their association with the transverse perineal muscle. The anterior ones appear only in women through a urogenital diaphragm defect whilst the less frequent posterior hernias protrude through a defect in the levator coccygeal muscle.1 Perineal hernias are also etiologically divided into: primary (congenital or acquired) and secondary hernias.3 The latter are generally a consequence of major pelvic surgery, such as abdominal perineal resection of the rectum, pelvic exenteration and perineal prostatectomy, or a trauma injury of the perineum.4 Incidence of this variety ranges between 0.6% and 7%, depending on the surgery preceding it,4 whilst its prevalence has been estimated at 0.34%.5 Furthermore, primary perineal hernias which are more common in women than in men at a rate of 5:1, are a less frequent clinical condition than the secondary type.6 One of the possible risk factors for primary perineal hernias has been reported as the increase in intra-abdominal or pelvic pressure during pregnancy, birth and in obesity, together with a tobacco habit, chronic ascites and recurrent infections or acquired weakness of the pelvic floor.1 In the case of congenital type chromosome changes have been reported which correspond to monosomy X, in foetuses with perineal hernias.7

The aim of this article is to: present the case of a primary posterior perineal hernia, in a male patient, associated with dolichocolon, a condition which to our knowledge has never been reported.

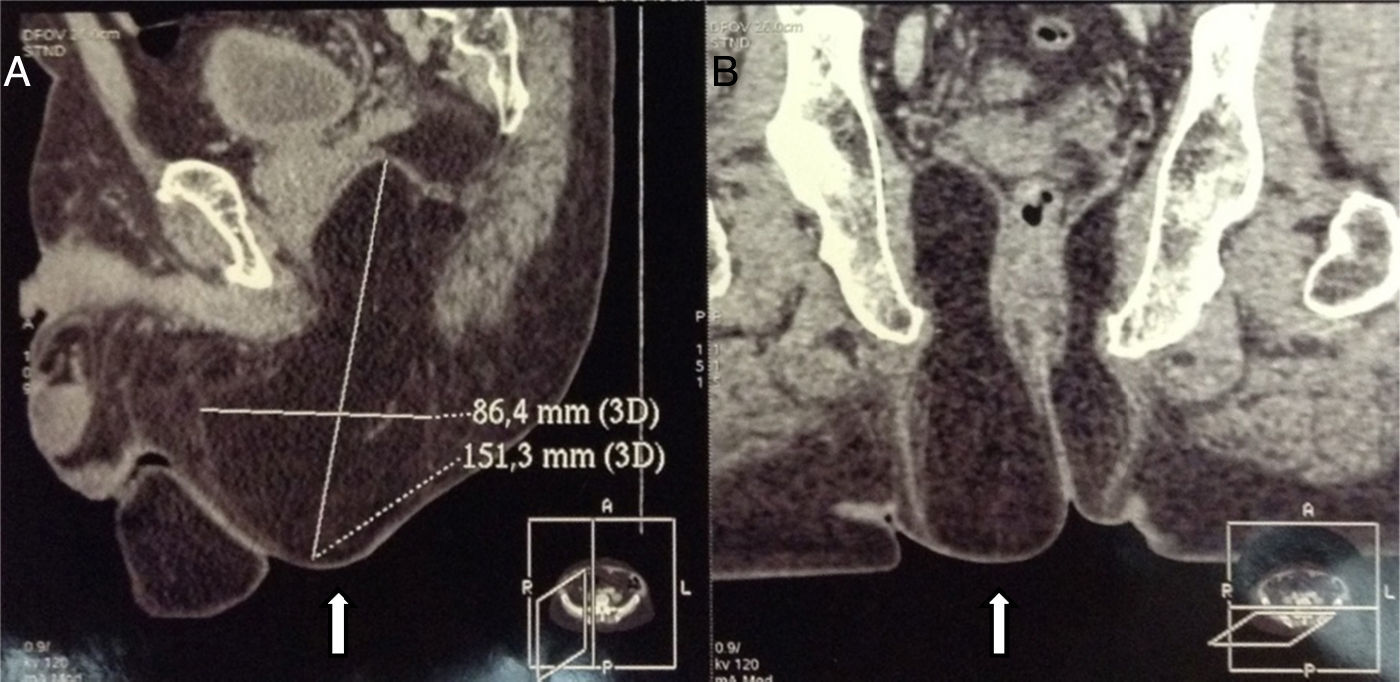

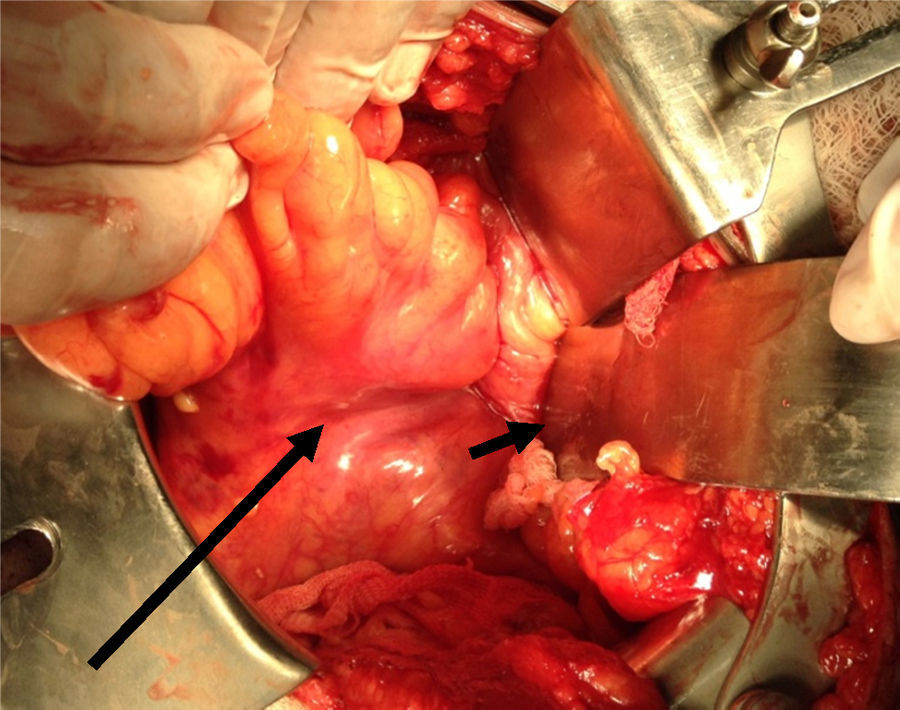

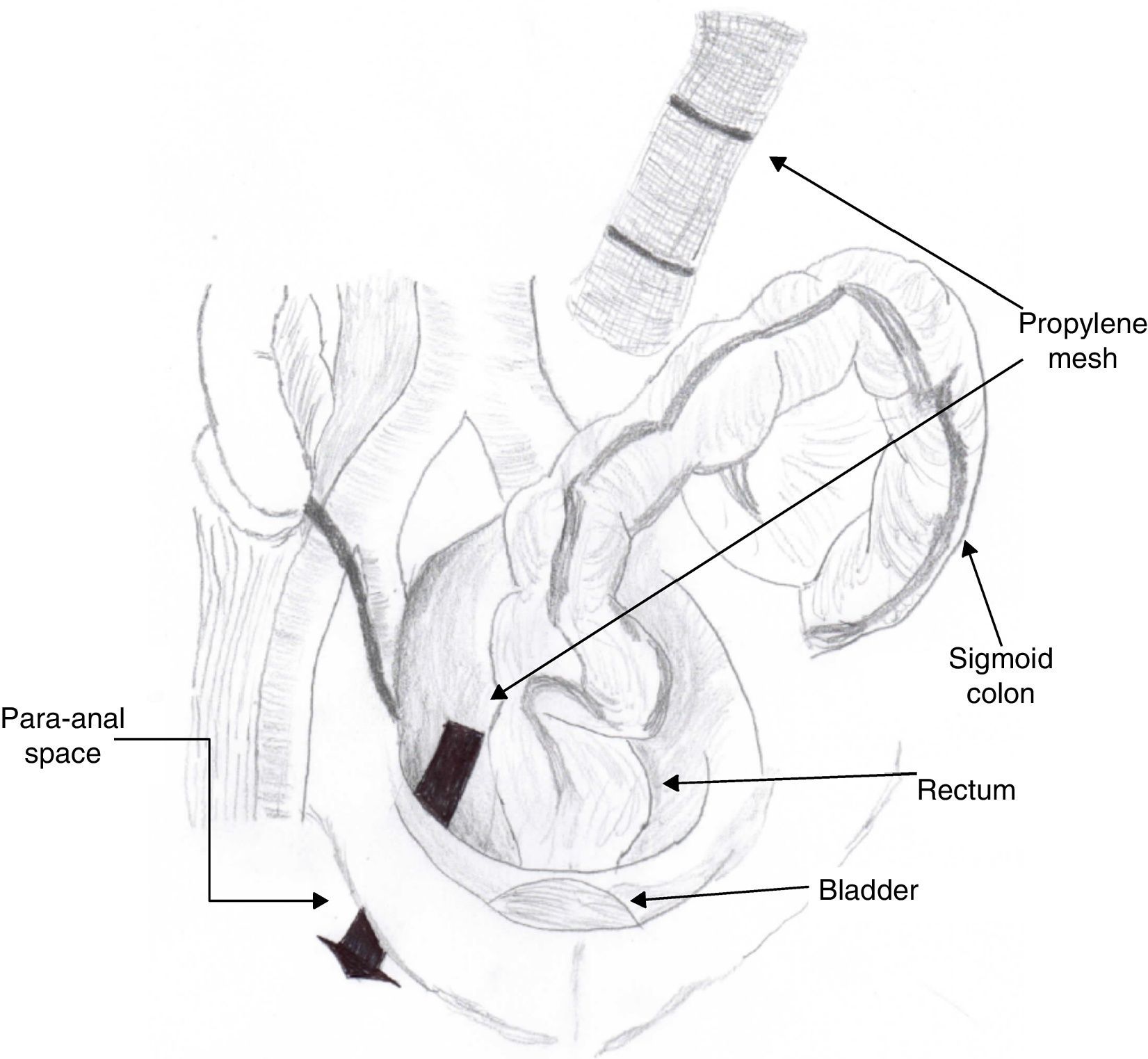

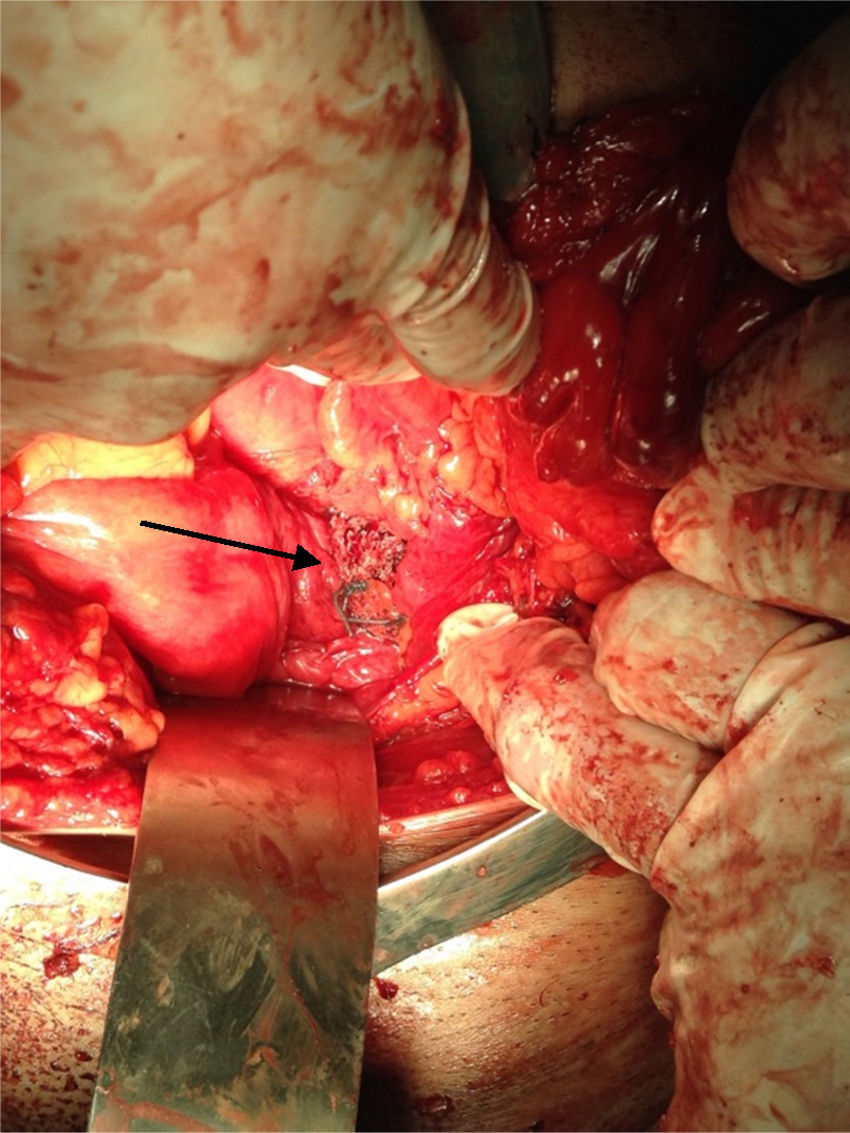

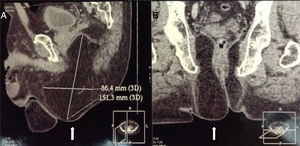

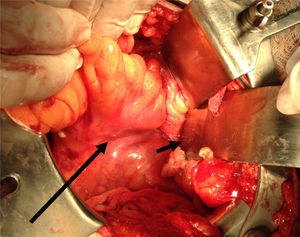

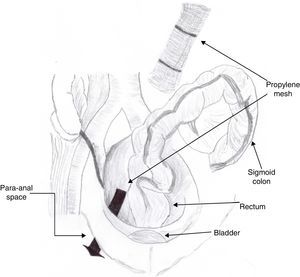

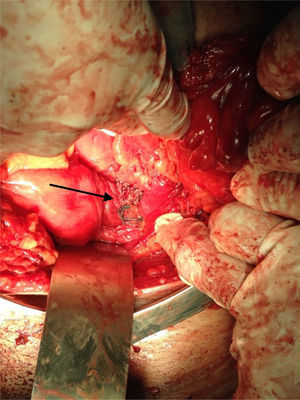

Clinical caseA 71-year old man presented with a perineal tumour of 40-year evolution. He had undergone left inguinal herniorrhaphy with tension repair 22 years previously, and transurethral prostatic resection with benign hyperplasia 2 years previously. His vital signs on admission were: blood pressure of 120/80mmHg, heartbeat of 75 per minute, breathing rate of 18 per minute and body temperature of 36.9°C. Physical examination revealed a soft 4cm×3cm lump, in the right para-anal region, which over the last few years had been associated with constipation and progressively intensive pain when sitting down (Fig. 1) The tumour increased in volume during the Valsalva manoeuvre and a defect was found in the perineum of approximately 4cm diameter, during digital reduction of the mass. Rectal examination did not show any changes in the rectum and anal canal. Laboratory findings showed: haemoglobin of 13g/dl, 41% hematocrit, white blood count in whole blood of 9200/mm3, platelet calculation of 244,000/mm3, standardised international relationship of 1.4 fibrinogen levels of 310mg/dl, partial thromboplastin time of 24.2s and prothrombin time of 15.2s. Computed tomography of the pelvis showed an increase in the prerectal space and a segment of epiplon through the pelvic floor towards the perineum region through a ring of 4.6cm diameter (Fig. 2). Since the hernia was symptomatic, the patient underwent abdominal surgical intervention, through a lower midline incision. During the operation a hernia defect of approximately 4cm was observed, between the transverse perineal muscles and the coccygeal muscle of the right pelvic floor. A peritoneal sac containing sigmoid colon loops which were excessively long and redundant, and also a portion of the right wall of the extraperitoneal rectum protruded (Fig. 3). The peritoneal sac and its content were released from their surrounding attachments and a reduction of the abdominal cavity was then performed. For pelvis floor reconstruction a polypropylene mesh 10cm long and 4cm wide was placed inside the hernia defect (Figs. 4 and 5), fixed with non absorbable 2-0 sutures to the lateral pelvic ligaments and the sacrum fascia (Fig. 6), as shown. The mesh and pelvic floor was covered with peritoneum and sigmoidectomy with primary termino-terminal colorectal anastomosis was then performed, together with rectopexy and loop ileostomy as a means of protection of the anastomosis. The immediate postoperative period passed without complications and the patient was discharged from hospital 7 days following surgery. During the 10 month follow-up, the physical examination and monitored computed tomography did not show any evidence of recurrent symptoms or of perineal hernia.

Stamatiou et al.8 reported that the initial description of an acquired primary perineal hernia was by De Garangeot in1743, but Moscowitz described surgical management for the first time in 1916. This type of perineal hernia is extremely rare, and only almost 100 adult cases of it have been reported in the medical literature,6 whilst for the congenital variety only approximately 3 cases have been described.9

Primary perineal hernias are more common between the ages of 40 and 60, and in women, probably due to the wider breadth of their pelvis compared with men and the progressive weakening of their endopelvic muscles and fascias, resulting from pregnancies and births.10 In a man, the most vulnerable site for the perineal hernia is in the muscular fibres of the levador ani muscles fibres or between this muscle and the coccygeal muscle, behind the transverse perineal muscle in the para-anal or ischial-coccygeal region. Clinical manifestation is a tumour along the inferior margin of the gluteus maximus muscle or the posterior perineum, between the anus and the ischial tuberosity.3,6 It is probable that the cavernous bulb of the penis and the prostate, on occupying space in front of the transverse perineal muscle, prevent anterior perineal hernia in the male.11

In absence of a background of trauma or pelvic surgery, diagnosis of a primary perineal hernia in the adult patient is difficult. Although generally asymptomatic, its clinical manifestations may include perineal malaise or pain when sitting or upright, urinary dysfunction and intestinal obstruction. Examination usually reveals a gluteal or perineal mass which protrudes spontaneously and which is aggravated by the Valsalva manoeuvre, and skin ulceration. Differential diagnosis of the posterior perineal hernias must therefore take into account: haematomas, lipomas, fibromas, cystic lesions, perineal or peri-anal abscesses, rectocele, cystocele, rectal prolapsed, and, above all, sciatic hernias.1 For this reason, clinical diagnosis of a perineal hernia must be confirmed by computed tomography or magnetic resonance.12,13 The complications of perineal hernias, such as intestinal obstruction, incarceration and strangulation, are infrequent due to the extension of the defect and the elasticity of the tissues surrounding it.14

Many perineal hernias may be treated conservatively, but surgery, which includes the reduction of the content of the sac and repair of the pelvic floor defect, is usually considered when cases are symptomatic (malaise and pain), where there is erosion above the hernial saco or intestinal obstruction.15 In this respect, many approaches have been described, but given the low prevalence of these hernias there is no agreement in the current literature about which is better, and an individual strategy must therefore be developed. The perineal approach is more direct and simpler, but exposure may be inappropriate with the possibility of provoking intestinal damage, as well as being associated with a recurrence of the hernia >16% of cases.16,17 The transabdominal approach offers better exposure for mobility and dissection of the hernial sac content, and also means other abdominal procedures may be executed at the same time.18 Combinations of both approaches have also been repoarted.19 Lastly, the first laparoscopic repair of a perineal hernia was performed in 2002, and this procedure may be considered in selected patients.20 Several techniques have also been described for the repair of the pelvic floor, including primary suture of the hernial defect and the implantation of synthetic or biological meshes with fixation to bony structures, muscles and ligaments.21 Other reported techniques include the use of autogeneous tissue, such as the rotation of the gracilis muscle described in 1978, as an alternative in the repair of perineal defects.22 It is difficult to know the rate of recurrence of each approach and technique mentioned since relatively few cases have been studied and the repair methods of the pelvic floor are not always clearly described. However, the total rate of recurrence in surgical repair of perineal hernias has been reported in up to 30% of cases, above all in repairs using direct suture and a perineal surgical approach.21,23

The case we describe is relevant because it is a rare clinical entity, and because it presents itself in patients who are less frequently affected, such as men with posterior and primary type perineal hernias. Moreover, as far as we are aware, transabdominal repair using a roll of prosthetic material has not been described, nor has its association with dolichocolon. In this respect, it is probable that the redundant colon has acted as a risk factor in the development of the perineal hernia, on executing an increase of intra-abdominal pressure on the pelvic floor, similar to that which was communicated to patients with excessively long small intestines.5 The surgical procedure which we carry out in the colon and anus may be disputable, but the surgery for dolichocolon is a standard indication in patients with concomitant pathologies or symptoms which severely alter their quality of life.24

ConclusionsPrimary posterior perineal hernias in the male are very rare. The surgical approach and repair technique of the pelvic floor for perineal hernias should be individualised and this will depend on the patient's clinical condition, the surgeon's experience, the size of the hernia defect and the need to perform other abdominal procedures. At present the use of the mesh for pelvic floor reconstruction should always be considered. The presence of the dolichocolon could have contributed to the gradual development of the perineal hernia in the case we present.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Méndez-Ibarra JU, Mora-Sevilla JM, Evaristo-Méndez G. Hernia perineal posterior primaria asociada a dolicocolon. Cir Cir. 2017;85:181–185.