Intestinal pneumatosis (IP) is defined as the presence of air within the submucosa and subserosa of the intestinal wall1. It is an ominous radiological sign that prompts urgent surgical consultation given that its presence implies ischemia of the intestinal wall, which has a high risk of intestinal perforation. In some exceptional cases it can be due to cystic pneumatosis, a rare cause of primary intestinal pneumatosis. The main causes for IP are mechanical colonic obstruction, inflammatory bowel disease, infectious ailments, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or pharmacologically induced2. Colorectal carcinoma is presently the main cause of colonic obstruction and thus of colonic IP.

Currently emergent surgical intervention is the treatment of choice when IP is present regardless of the high morbidity and mortality rate and the elevated number of stoma formation.

In select cases an endoscopic colonic self-expanding metallic stent (SEMS) placement has proven to be a safe alternative to emergent surgery with less associated complications3. Stent placement was usually reserved as a palliative treatment for inoperable tumors. Nowadays its placement is considered a viable option as a bridge to surgery for patients with resectable disease, allowing colonic decompression and further optimization of the patient for future surgical intervention with lower rate of complications4.

In this study we evaluate de results of endoscopic SEMS placement in patients with colonic obstruction associated with cecal pneumatosis.

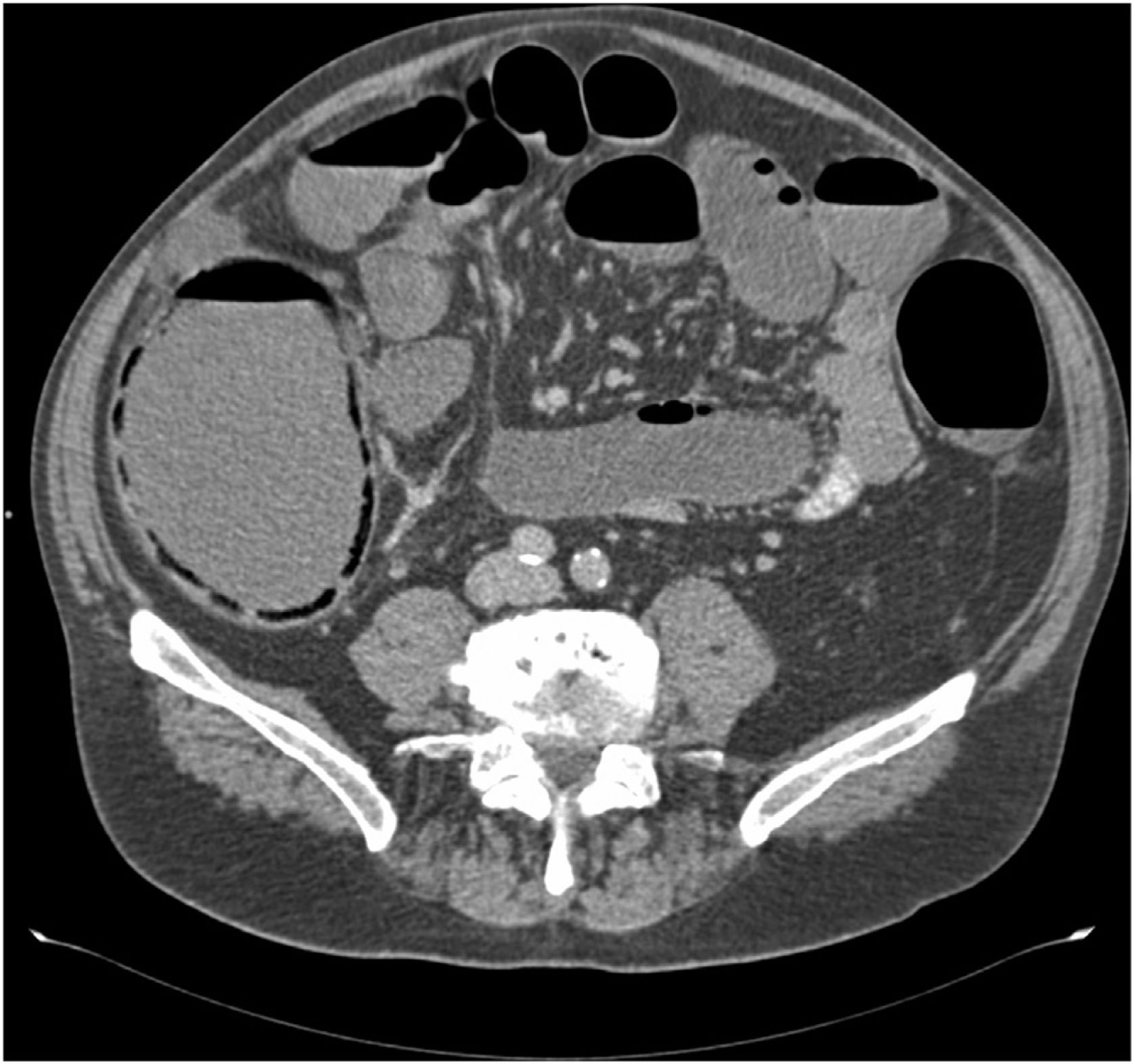

A retrospective descriptive cohort study of patients diagnosed with obstructive colorectal carcinoma associated with cecal pneumatosis by a CT scan, between January 2012 and December 2017 who were treated with endoscopic SEMS. Cecal viability was defined as the absence of complications after stent placement.

Nine patients with obstructive colorectal carcinoma were treated with endoscopic SEMS, 5 male and 4 female with a mean age of 76 (52–91). At the time of diagnosis all were hemodynamically stable and had no signs of sepsis. The mean cecal diameter was 10.5 cm (8–12.4) (Fig. 1).

Eight patients had regained bowel function within the first 24–48 h after treatment. One patient required emergency surgery due to failed stent and persistent bowel obstruction. Those with functioning stents had an uneventful recovery with a mean stay of nine days (3–16). Six patients were later admitted for elective surgical intervention after being optimized for surgery in a mean period of 24 days (5–51) after stent placement. Two patients were not considered for elective surgery and thus the stent served as a palliative treatment.

The pathophysiology of IP is not completely understood, it is believed that it is due to an interruption of the intestinal barrier secondary to insufficient blood flow making it permeable to gas which diffuses to the submucosa and subserosa of the intestinal wall.

Emergent surgical intervention is the treatment of choice in patients with an obstructive colorectal carcinoma with a high morbidity and mortality rate, when compared to elective surgery which has a low morbidity and mortality rate 0.9 % and 6% respectively5. Emergency surgery is also associated with a higher rate of permanent stomas and its negative impact on quality of life.

The use of endoscopic SEMS as a palliative treatment of obstructive colorectal carcinoma has increased over the years6. Later on, this treatment option has been proposed as a “bridge” treatment prior to elective surgery. This approach provides an opportunity to optimize the patient prior to a surgical intervention and improve the outcomes and decrease the rate of permanent stomas4. A systematic review demonstrated that SEMS had a success rate of 92%, with a lower length of stay (LOS), stoma formation, and adverse events7.

There is controversy surrounding the oncological outcomes of stent placement prior to surgical intervention, given that it has been associated with a higher rate of local recurrence due to tumor manipulation and possible local perforation8. Based on the current literature the use of SEMS as a first treatment option should be reserved for patients with metastatic disease, and ASA > 3 without metastatic disease, thus providing a window of opportunity to ameliorate the patient’s condition for an eventual elective surgery 5–10 days after stent placement9.

A few case reports can be found in the current literature, describing the use of endoscopic SEMS in patients with IP.

Sings and symptoms of intestinal ischemia like leukocytosis, elevated serum lactate, renal failure, and elderly patients should be promptly identified and in these cases, surgery shouldn’t be delayed10. Adequate selection of patients, candidates for a conservative treatment, should be undertaken to prevent unfavorable outcomes and improve morbidity and mortality rates.

In our series, despite the presence cecal pneumatosis in radiology studies, it can be assumed that there was no intestinal ischemia given that the patients had uneventful recoveries after SEMS placement.

As a conclusion, cecal pneumatosis doesn’t always imply the presence of transmural ischemia in patients with an intestinal obstruction due to colorectal carcinoma. Endoscopic SEMS placement is a safe procedure as a bridge to surgery thus preventing the possible complications associated with an emergent surgical intervention.

Conflicts of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.