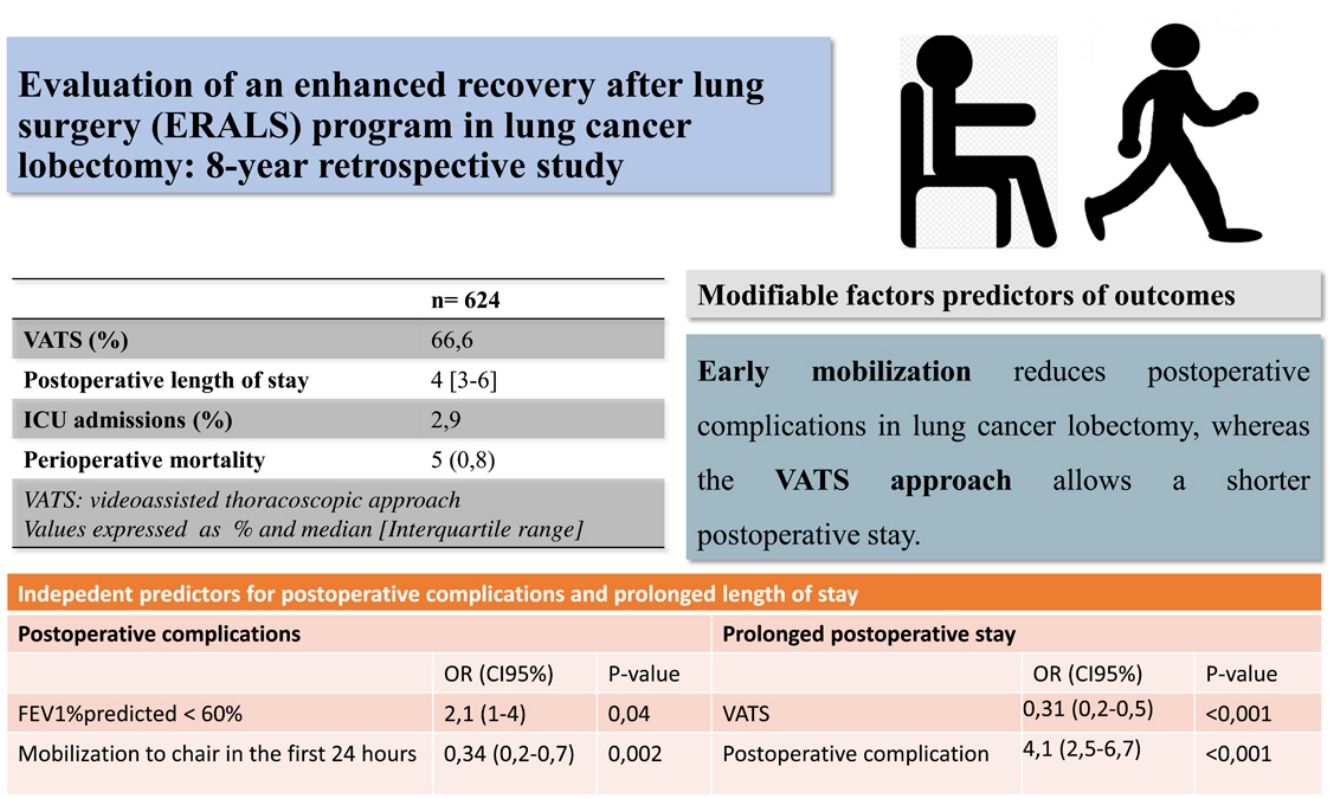

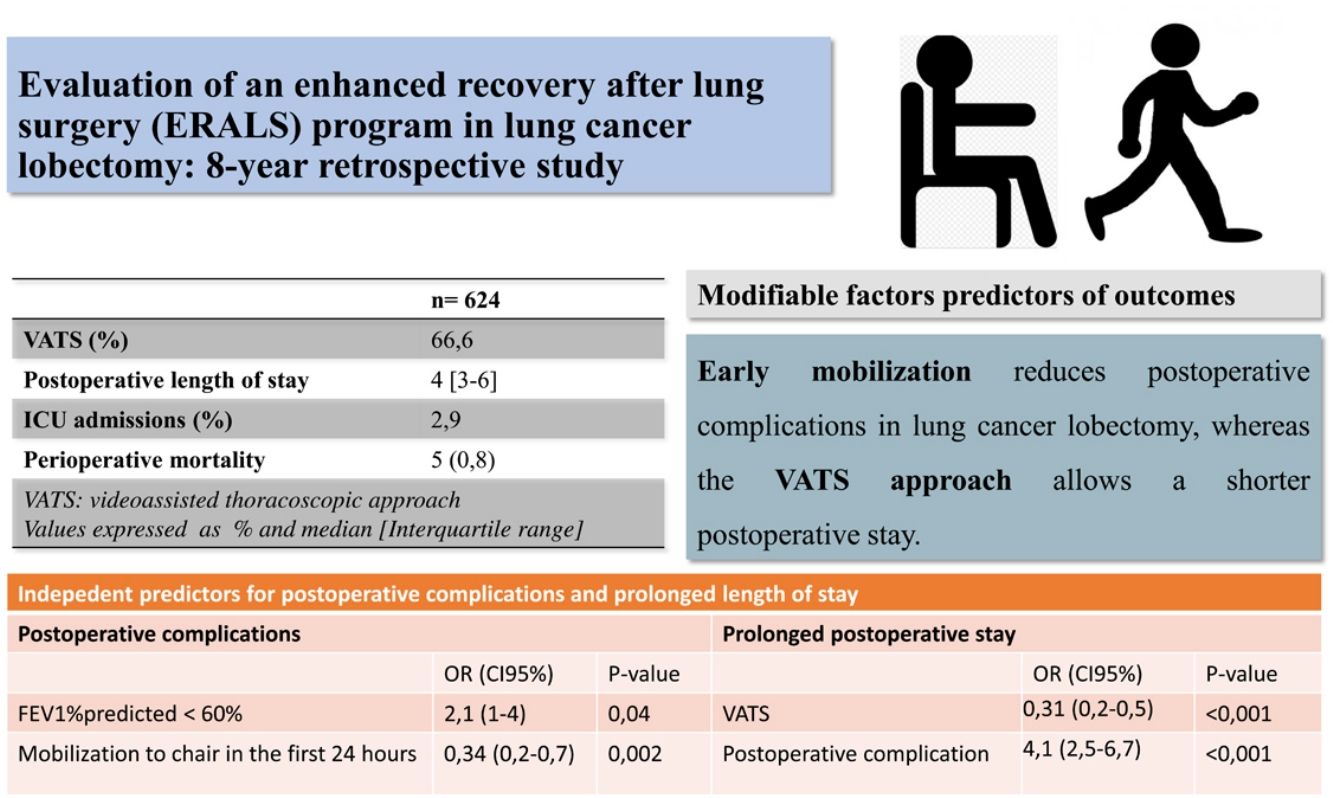

Enhanced recovery after lung surgery (ERALS) protocols have proven useful in reducing postoperative stay (POS) and postoperative complications (POC). We studied the performance of an ERALS program for lung cancer lobectomy in our institution, aiming to identify which factors are associated with a reduction of POC and POS.

MethodsAnalytic retrospective observational study conducted in a tertiary care teaching hospital involving patients submitted to lobectomy for lung cancer and included in an ERALS program. Univariable and multivariable analysis were employed to identify factors associated with increased risk of POC and prolonged POS.

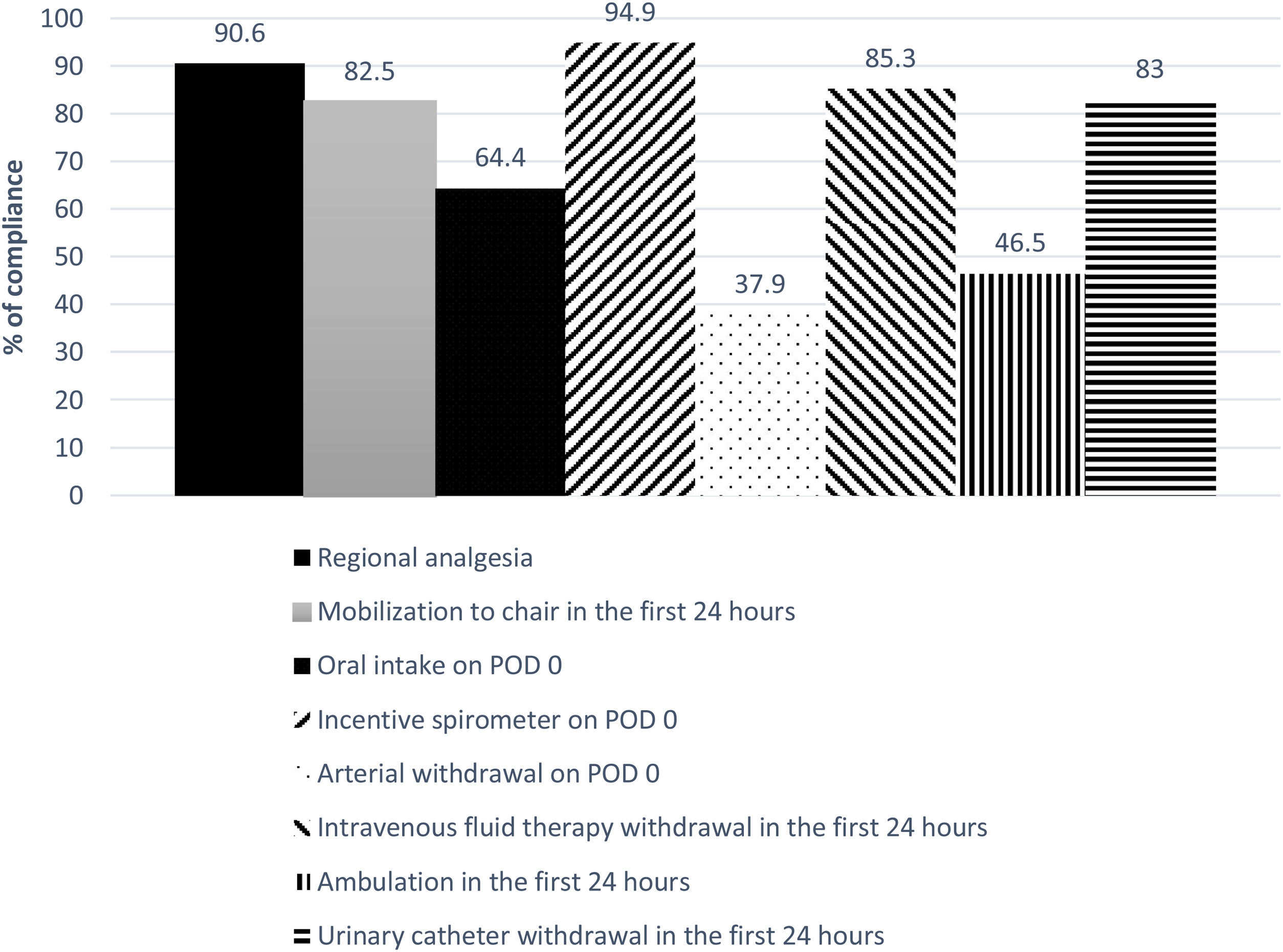

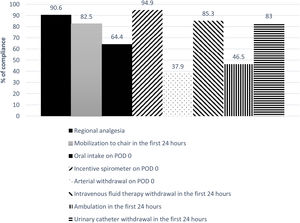

ResultsA total 624 patients were enrolled in the ERALS program. The median POS was 4 days (range 1–63), with 2.9% of ICU postoperative admission. A videothoracoscopic approach was used in 66.6% of cases, and 174 patients (27.9%) experienced at least one POC. Perioperative mortality rate was 0.8% (5 cases). Mobilization to chair in the first 24h after surgery was achieved in 82.5% of cases, with 46.5% of patients achieving ambulation in the first 24h. Absence of mobilization to chair and preoperative FEV1% less than 60% predicted, were identified as independent risk factors for POC, while thoracotomy approach and the presence of POC predicted prolonged POS.

ConclusionsWe observed a reduction in ICU admissions and POS contemporaneous with the use of an ERALS program in our institution. We demonstrated that early mobilization and videothoracoscopic approach are modifiable independent predictors of reduced POC and POS, respectively.

Los programas de recuperación intensificada en cirugía de pulmón (por sus siglas en inglés, ERALS) han demostrado ser útiles para reducir la estancia hospitalaria y las complicaciones postoperatorias. Estudiamos los resultados de la aplicación de un programa ERALS para lobectomía por cáncer en nuestro centro con la intención de identificar aquellos factores que se relacionan con la reducción de las complicaciones y la estancia.

MétodosEstudio observacional retrospectivo en pacientes sometidos a lobectomía por cáncer de pulmón e incluidos en un programa ERALS. Se empleó análisis univariable y multivariable para identificar los factores de riesgo de complicaciones y estancia prolongada.

ResultadosUn total de 624 pacientes se inscribieron en el programa ERALS. La estancia postoperatoria mediana fue de 4 días (1-63), con una tasa de ingreso en la UCI del 2,9%. El abordaje videotoracoscópico fue empleado en el 66,6% de los casos, y la tasa de complicaciones postoperatorias fue del 27,9%, con una tasa de mortalidad del 0,8% (5 casos). La no movilización en las primeras 24h, y el FEV1% inferior al 60% del previsto, se identificaron como factores de riesgo de complicaciones; mientras que el abordaje mediante toracotomía y la presencia de complicaciones predijeron la estancia prolongada.

ConclusionesObservamos una reducción en la estancia hospitalaria y en los ingresos postoperatorios en la UCI concomitante a la puesta en marcha de un programa ERALS en nuestro centro. La movilización precoz y el abordaje quirúrgico videotoracoscópico demostraron ser predictores independientes y modificables para la reducción de las complicaciones y para la duración de la estancia, respectivamente.

Enhanced recovery after lung surgery (ERALS) protocols have shown promising results in terms of improving clinical outcomes in patients submitted to lobectomy for lung cancer.1–6 Video Assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery (VATS) together with early mobilization were soon identified as independent predictors of shorter postoperative stay (POS)3,5,7 and reduction of postoperative complications (POC).3,7,8 These measures, together with early restoring of oral feeding, avoidance of opioids in the postoperative period and chest tube removal politics are considered fundamental components of ERALS programs in recently published guidelines.9 Despite its possible benefits, the performance of ERALS reportedly varies significantly,10,11 which is likely attributable in part to variations in individual, organizational, or cultural factors that can hinder comprehensive implementation of these programs.12,13 The potential influence of these external factors may also make it difficult to identify independent and reliable predictors of outcomes and their variability between healthcare providers.2,13

At the end of 2012, we launched an ERALS program in our institution. Patients spent the day of surgery (postoperative day 0 [POD 0]) in the postanesthetic care unit (PACU) under direct supervision of the anesthesia team, commencing postoperative measures of the ERALS protocol on arrival in the PACU (Table 1). In the present work, we study the performance of our ERALS program 8 years after its launch. The primary objective is to evaluate the results of this ERALS program in terms of clinical outcomes and hospital stay. As a secondary objective, we intend to identify which factors are associated with increased risk for POC and prolonged POS.

Standards of care for oncologic lung resection surgery in our institution. Pre-ERALS versus ERALS periods.

| Pre-ERALS (absence of specific protocol) | ERALS | |

|---|---|---|

| Preoperative period | ||

| Recommendation for smoking cessation at least 4 weeks before surgery | AAD/ASD | Systematic advice by surgeon and anesthesiologistPatients referred to specific anti-smoking office |

| Patient education/counseling in the surgeon's office | + | + |

| Prehabilitation for patients with borderline lung function or exercise capacity | ASD | + |

| Perioperative period | ||

| Oral carbohydrate loading two hours before surgery | − | − |

| Avoidance of routine preoperative sedation | − | − |

| Preferent use of epidural/paravertebral block | + | + |

| Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in major lung resection procedures | Systematic postoperative use of low-molecular-weight-heparin.Mechanical prophylaxis ASD | Like pre-ERALS |

| Routine use of antibiotic prior to skin incision | + | + |

| Systematic use of Chlorhexidine–alcohol instead of povidone-iodine solution for skin preparation | − | + |

| Use of VATS | ASD | + |

| Muscle-sparing technique if a thoracotomy is required | ASD | + |

| Systematic prophylaxis of perioperative nausea and vomiting | AAD | + |

| Perioperative maintenance of normothermia with convective active warming devices | AAD | + |

| Use of one single chest tube | ASD | + |

| Lung-protective strategies used during one-lung ventilation | − | AAD |

| Use of short-acting volatile or intravenous anesthetics | AAD | + |

| Use of balanced crystalloids | + | + |

| Systematic extubation in operating room (unless specific conditions) | + | + |

| Postoperative period | ||

| Incentive spirometer in the first two hours after surgery | − | + |

| Preferential use of acetaminophen and NSAIDs regularly administered unless contraindications exist | AAD | + |

| Systematic use of dexamethasone to prevent PONV and reduce pain | − | AAD |

| Continuation of preoperative beta-blockers during the postoperative period | AAD/ASD | + |

| Mobilization to chair | On POD 1 | On POD 0 (4–6h after arrival in the PACU) |

| Postoperative chest X-ray | In the first 24h | 2–4h after arrival in the PACU |

| Arterial catheter withdrawal | AAD | On the first 4–6h after arrival in the PACU |

| Oral intake | ASD | 4h after arrival in the PACUClear liquids by evening-night |

| Urinary catheter withdrawal in the morning of POD1 | − | + |

| Physiotherapist instructed non-complex training exercise and promoted ambulation in the morning of POD 1 | + | + |

| CD: avoidance of routine application of external suction | + | + |

| Use of digital drainage systems always when available | − | + |

| CD removal even if the daily serous effusion is of high volume (up to 450ml/24h) | ASD | + |

+: systematically applied; −: non applied; AAD: at the anesthesiologist's discretion; ASD: at the surgeon's discretion; CD: chest drain; ERALS: enhanced recovery after lung surgery; NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PACU: postanesthetic care unit; POD: postoperative day. PONV: postoperative nausea and vomiting; VATS: video assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

This analytic retrospective observational study was carried out in a tertiary care teaching hospital. After obtaining authorization from the hospital's ethics committee, we studied data of patients included in an ERALS program in our institution. We included all adult patients (≥18 years) who had undergone scheduled lobectomy for suspected or confirmed lung cancer between 1 December 2012 and 31 October 2020. Exclusion criteria were emergency surgery, non-oncological lung resection surgery, and oncological lung surgery involving other chest wall structures. We reviewed the electronic and paper-based medical records (available in digitized format) up to 12 months after discharge from hospital. We recorded patient characteristics, presence of comorbidities, and data on intervention and perioperative care (Table 2). Major postoperative complications were defined according to the modified criteria proposed by previous authors,14 applying the Clavien-Dindo classification based on the treatment required15 (Table 3). Perioperative mortality (occurring within 30 days after the operation or later if patient was still an inpatient,16 reoperation rate during admission and hospital readmissions within 30 days of discharge were also recorded (Table 2). A prolonged POS was defined as≥the 75th percentile17,18 (≥ six days). Prolonged air leak was defined as persisting for more than 5 days after the intervention.19,20 Data collection was carried out between 1 March and 30 November 2020. Patients’ data were anonymized. We have reported this study in accordance with the STROBE criteria for observational studies.

Distribution of individual's characteristics, perioperative data, and outcomes of patients submitted to lung cancer lobectomy under an ERALS program.

| n=624 | |

|---|---|

| Individual characteristics | |

| Age (years) | 64.8±11 |

| Male sex | 474 (75.8) |

| Weight (kg) | 76.9±15 |

| BMI | 27.5±5 |

| History of smoking | 500 (83.8) |

| Pack-year | 52 [0–175] |

| Hypertension | 315 (50.6) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 141 (22.6) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 59 (9.5) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 36 (5.8) |

| COPD | 208 (34.8) |

| COPD≥3 grade GOLD | 21 (3.4) |

| OSAS | 44 (7.1) |

| ASA grade≥3 | 354 (56.8) |

| FVC % | 97.2±17 |

| FEV1% | 84.8±20 |

| Individuals with FEV1%predicted<60%d | 68 (10.9) |

| Individuals with DLCO %predicted<60%d | 104 (16.7) |

| Perioperative factors and outcomes | |

| VATS approach | 399 (66.6) |

| Analgesia via epidural/paravertebral/intercostal catheters | 558 (90.6) |

| Infusion of vasopressors during the intervention | 33 (5.3) |

| Reoperation during admission | 15 (2.4) |

| Admission to the ICU | 18 (2.9) |

| Readmission to the ICU | 21 (3.4) |

| POS | 4 [1–63] |

| Prolonged POS | 185 (29.9) |

| Mortality at 30 days/during admission | 5 (0.8) |

| POCa | 174 (27.9) |

| Respiratory POCb | 161 (25.8) |

| Cardiovascular POCc | 27 (4.3) |

| Individual POC | 259 (41.5) |

| Subcutaneous/mediastinal emphysema | 83 (13.4) |

| Atelectasis | 23 (3.7) |

| Pneumonia | 8 (1.3) |

| Suspected pneumonia | 1 |

| Empyema | 2 |

| Bronchospasm | 5 |

| Hemo/pneumothorax | 14 (2.2) |

| Bronchopleural fistula | 2 |

| Reintubation requirement | 7 (1.1) |

| Chest wall hematoma | 1 |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome ≥ moderate | 4 |

| Hypoxemia requiring therapy | 9 (1.4) |

| New-onset atrial fibrillation | 17 (2.7) |

| Myocardial infarction/injury | 1 |

| Other cardiovascular complications (congestive cardiac failure, major cardiac arrhythmia other than atrial fibrillation) | 9 (1.4) |

| Prolonged air leakd | 64 (10.3) |

| Postoperative ileus | 1 |

| Fever of unknown origin | 2 |

| Othere | 6 (1) |

| Days of permanence of the CD (excluded cases with prolonged air leak)d | 3 (1–15) |

| Hospital discharge with CD | 43 (6.9) |

| Oral intake on POD 0d | 401 (64.4) |

| Incentive spirometer on POD 0 | 573 (94.9) |

| Mobilization to chair in the first 24h after surgeryd | 514 (82.5) |

| Ambulation in the first 24h after surgeryd | 290 (46.5) |

| Arterial withdrawal on POD 0 | 237 (37.9) |

| Intravenous fluid therapy withdrawal in the first 24h after surgery | 512 (85.3) |

| Urinary catheter withdrawal in the first 24h after surgery | 498 (83) |

| 30-Day readmissionf | 22 (3.5) |

| Emphysema/Pneumothorax | 4 |

| Dyspnea | 4 |

| Pneumonia/pleural empyema | 5 |

| Bronchopleural fistula | 2 |

| Other | 7 (1.1) |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI: body mass index; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CD: chest drain; DLCO%: diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide percentage of predicted; ERALS: enhanced recovery after lung surgery; FEV1% forced expiratory volume in the first second percentage of predicted; FVC: forced vital capacity percentage of predicted; GOLD: Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease; ICU: Intensive Care Unit; OSAS: obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; POC: postoperative complications; POD: postoperative day; POS: postoperative stay; VATS: video assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Data are listed as n (percentage) for categorical variables and mean±standard deviation or median [interquartile range] for continuous variables. Missing values have been excluded for the estimation of percentages.

Postoperative complications based on the treatment required (Clavien-Dindo classification15).

| Grade | Complication | n (%)a | %b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grado I Any complication without need for pharmacologic treatment or other intervention | – | – | – |

| Grade II Complication that requires pharmacologic treatment or minor intervention only | Chest wall hematoma | 1 | |

| Subcutaneous/mediastinal emphysema | 82 (13.1) | 47.1 | |

| Prolonged air leak | 64 (10.2) | 36.8 | |

| Atelectasis | 23 (3.7) | 13.2 | |

| Bronchospasm | 4 (0.6) | 2.3 | |

| Hypoxemia requiring oxygen therapy | 8 (1.3) | 4.6 | |

| Pneumonia | 2 (0.3) | 1.1 | |

| Suspected pneumonia | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Pleural empyema | 2 | 1.1 | |

| New onset atrial fibrillation | 14 | 8 | |

| Myocardial infarction/injury | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Other cardiovascular complications (congestive cardiac failure, major arrhythmia other than atrial fibrillation) | 9 (1.4) | 5.2 | |

| Postoperative ileus | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Fever of unknown origin | 2 | 1.1 | |

| IIIa Complication that requires intervention without general anesthesia | Hemo/pneumothorax | 10 (1.6) | 5.7 |

| Upper gastrointestinal bleeding | 1 | 0.5 | |

| IIIb Intervention requires general anesthesia | Subcutaneous/mediastinal emphysema | 1 | 0.5 |

| Bronchopleural fistula | 1 | 0.5 | |

| IVa Single organ dysfunction requiring intensive care unit management and life support | New onset atrial fibrillation | 3 | 1.7 |

| Bronchospasm | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Hypoxemia requiring oxygen therapy | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Hemo/pneumothorax | 4 (0.6) | 2.3 | |

| Pneumonia | 6 (1) | 3.4 | |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome≥moderate | 4 (0.6) | 2.3 | |

| Reintubation | 7 (1.1) | 4 | |

| IVb Multiorgan dysfunction requiring intensive care unit management and life support | Sepsis | 1 | 0.5 |

| Grade V Any complication leading to the death of the patient. | Broncho-pleural fistula | 1 | 0.5 |

| Intestinal volvulus | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Usual interstitial pneumonia | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Surgical bleeding | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Major peripheral ischemic event | 1 | 0.5 |

Specific perioperative management of ERALS patients is detailed in Table 1. VATS approach is systematically used except in patients in whom a pneumonectomy, superior sulcus tumor, or tumors that invade the chest wall are prevented. Patients spent the first postoperative night in the PACU. Incentive spirometry instructed by the nurse was promoted in the first two hours after arrival at the PACU, with the beginning of oral tolerance to clear liquids 4h after admission and mobilization to the chair on the evening of POD 0 if the patient's conditions allowed it. Patients were transferred to the ward on the morning of POD 1 unless specific conditions delayed transfer. Any urinary catheter or intravenous fluid therapy was removed on arrival in the ward, and patients were encouraged to immediately sit in a chair. On the morning of POD 1, a physiotherapist worked on the patients, instructing them in a non-complex training exercise and promoting ambulation. Intravenous or oral opioids were avoided and used only for breakthrough pain not controlled by non-steroidal analgesics and/or regional techniques. Epidural or paravertebral catheters were usually kept in situ for the first 48h after surgery and were not considered an impediment to ambulation. Regional analgesia was usually maintained by infusion of ropivacaine 1–1.5mg/ml and fentanyl 1–2μg/ml in saline, the infusion rates being 5–7 and 7–12ml/h for epidural and paravertebral/intercostal catheters, respectively. Digital chest drain was systematically used (Thopaz Chest Drain System®, Medela, Spain) and removed on POD 2 in the absence of air leak and if serous output was less than 450ml/24h. Patients with prolonged air leak were discharged with portable chest drain at the surgeon's discretion.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed by the primary researcher using SPSS version 22.0. © for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Continuous variables are presented as the mean, standard deviation and median with range (minimum and maximum values), and categorical variables as absolute and marginal frequencies and proportions. For those variables with missing data>5%, the replacement of missing values by multiple imputation (Regression Method) was used. The proportions for categorical variables with less than 5% missing values were estimated from the original available data. Normality of continuous variables was examined using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and the homogeneity of variances with the Levene test. We used Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U test and χ2 test (or Fisher's test) to assess the behavior of the means and proportions of continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Variables associated with increased risk of POC and prolonged POS were analyzed by multivariable analysis (binary logistic regression).

ResultsA total of 624 patients were enrolled in the ERALS program. Table 2 shows the distribution of patient characteristics and perioperative data, together with outcomes. A VATS approach was used in 66.6% of the cases, with a prominent use of regional analgesia via an epidural, paravertebral, or intercostal catheter (90.6%). Admission to the ICU was anecdotal (2.9%). The median POS was 4 days (interquartile range 3–6 days). A total of 259 individual complications were experienced by 174 patients (27.9%) (Tables 2 and 3). The overall perioperative mortality rate was 0.8% (5 cases). The main cause of in-hospital mortality was respiratory failure (one case due to persistent bronchopleural fistula, another case in a patient reoperated for intestinal volvulus, and a patient with acute exacerbation of pre-existing usual interstitial pneumonia). One patient died during the intervention due to uncontrollable bleeding, and one due to major peripheral ischemic event in the postoperative period. Univariable analysis of mortality showed no risk factors association.

The global compliance with the different components of the ERALS program is shown in Fig. 1. Mobilization to chair in the first 24h after surgery was achieved in 82.5% of cases. Of these, a total 46.5% of patients achieved ambulation in the first 24h. Absence of mobilization to chair in the first 24h after surgery together with preoperative FEV1% less than 60% predicted were identified as independent risk factors for POC (Table 4), while non-VATS approach and the presence of POC predicted prolonged POS (Table 5).

Variables associated with the incidence of postoperative complications.

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR (CI 95%) | p-Value | OR (CI 95%) | p-Value |

| Male sex | 1.9 (1.2–3) | 0.03 | 1.4 (0.8–2.6) | 0.218 |

| Age | 0.01 | 0.093 | ||

| Age (≥65 years) | 1.6 (1.1–2.3) | 0.02 | 1.6 (1–2.7) | 0.341 |

| VATS | 1.1 (0.8–1.7) | 0.326 | ||

| FEV1% | <0.001 | 0.593 | ||

| FEV1%<60% | 3 (1.7–5.2) | <0.001 | 2.1 (1–4) | 0.04 |

| DLCO%<60% | 2.5 (1.5–3.9) | <0.001 | 1.8 (0.9–3.2) | 0.092 |

| COPD GOLD≥3 | 5.1 (2–13) | <0.001 | 1.9 (0.5–8.2) | 0.561 |

| ASA grade≥3 | 1.8 (1.2–2.6) | 0.002 | 1 (0.6–1.6) | 0.274 |

| Ambulation in the first 24h after surgery | 0.5 (0.4–0.7) | 0.041 | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 0.096 |

| Mobilization to chair in the first 24h after surgery | 0.3 (0.17–0.4) | <0.001 | 0.34 (0.2–0.7) | 0.002 |

| Oral intake on POD 0 | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.01 | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 0.721 |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists classification; BMI: body mass index; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DLCO%: diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide, percentage of predicted; FEV1%: forced expiratory volume in the first second, percentage of predicted; GOLD: Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease; POD: postoperative day; VATS: video assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

Variables associated with prolonged postoperative stay.

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR (CI 95%) | p-Value | OR (CI 95%) | p-Value |

| Male sex | 1.5 (1–2.3) | 0.04 | 1.8 (1–3.4) | 0.614 |

| Age (≥65 years) | 1.3 (0.9–1.8) | 0.273 | – | – |

| VATS | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) | <0.001 | 0.31 (0.2–0.5) | <0.001 |

| FEV1%<60% | 1.6 (1–2.7) | 0.05 | 1 (0.4–2.5) | 0.417 |

| DLCO%<60% | 1.6 (1–2.5) | 0.03 | 1.6 (0.8–3.3) | 0.142 |

| COPD | 1.9 (1.4–2.8) | <0.001 | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 0.871 |

| COPD GOLD≥3 | 1.5 (0.6–3.8) | 0.342 | – | – |

| ASA grade≥3 | 1.6 (1.1–2.3) | 0.01 | 1 (0.6–1.6) | 0.312 |

| Ambulation in the first 24h after surgery | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.009 | 1 (0.5–2.1) | 0.146 |

| Mobilization to chair in the first 24h after surgery | 0.4 (0.3–0.7) | <0.001 | 0.8 (0.4–1.7) | 0.621 |

| Oral intake on POD 0 | 0.7 (0.5–1) | 0.05 | 1 (0.9–2.4) | 0.921 |

| POC | 4.2 (2.8–6) | <0.001 | 4.1 (2.5–6.7) | <0.001 |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists classification; BMI: body mass index; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DLCO%: diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide, percentage of predicted; FEV1%: forced expiratory volume in the first second, percentage of predicted; GOLD: Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease classification; POC: postoperative complication; POD: postoperative day; VATS: video assisted thoracoscopic surgery.

A total 10.3% of the cases experienced air leak lasting more than 5 days. The median duration of permanence of the chest drainage (excluded cases with prolonged air leak) was 3 days (Table 2). A total of 43 patients (6.9%) were discharged with outpatient chest drainage due to prolonged air leak (42) or persistent pleural effusion (1).

DiscussionAs far as we know, this is the largest study of these characteristics published in our country.21 We observed 30-day mortality and POC rates consistent with recently reported data on ERALS lobectomy.2,4,22,23 Contradictory data have been reported regarding mortality depending on the population under study, the surgical approach, and the experience of the surgical teams, with figures ranging from zero3,4,7,24 to more than 3%.2 Different authors argue that 90-day mortality would better address procedure-related deaths that 30-day mortality, as some patients die beyond the first 30 days after surgery.25–27 In this sense, we could be underestimating the mortality attributable to the operation in our sample, even though we reported mortality figures beyond POD 30 if patient was still an inpatient. The POS in our sample was similar to, or slightly higher than, those recently published for ERALS programs, the median reported POS for lobectomies ranging from 4–52,5,7,22,28 to 1–2 days.3,24,28,29 Our published data on a historical cohort of patients who underwent lobectomy and were treated conventionally in the two years prior to the start of the program: pre-ERALS cohort (1 January 2010–30 November 2012)30 showed a median hospital stay of 7 days (interquartile range 6–8 days) and 41.6% of postoperative ICU admissions, this reflecting a clear change in trend following the launch of the ERALS program.

We demonstrated how mobilization to chair in the first 24h following intervention has a beneficial effect in terms of reducing POC, while VATS approach allowed a reduction in POS. These two modifiable factors have been previously addressed as independent predictors of outcomes.3,5,7,8 Other authors have reported that implementation of intensive early mobilization can drastically reduce the POS.3,24,29 Das Neves Pereira et al. reported that more than 90% of patients who participated in an aggressive ERALS program and underwent lobectomy for lung cancer achieved ambulation in the first postoperative hour, demonstrating an independent correlation between early ambulation and reduced POC.3 More recently, Mayor et al. reported a median POS of 1 day after VATS lobectomy in patients subjected to a specific early mobilization protocol.29 Although our results in terms of ambulation in the first 24h after surgery (46.5%) agree with some of those previously reported,4 they are still far from the best published rates, which are greater than 80% of patients achieving mobilization to chair or ambulation on POD 0.3,7,24,29

Some of the factors that may have influenced our improvable results are that we do not have a step-down unit for ERALS patients in our center and no nursing staff in the PACU are specifically dedicated to the care of these patients. Additionally, although the ERALS protocol is well established in the unit, the high turnover of patients, high levels of demand for care, and frequent replacement of personnel hinder homogeneous and effective application of the protocol on POD 0. Inadequate staffing and lack of financial resources have been identified as barriers to the optimal implementation of ERAS programs.12 Although we did not specifically analyze this aspect, the ratio of nurses to patients in the PACU (going from 1:4 to 1:6), together with the concomitant increase in demands for care caused by the launch of other ERAS programs, probably impacted our results. We must point out that the reduction in ICU admissions observed in the ERALS period could be explained due to institutional protocol changes congruent with the ERALS program rather than due to a difference in the clinical status of the patients. In the pre-ERALS period, patients were referred to ICU in the presence of moderate to severe impaired cardiopulmonary or renal function [examples include (but not limited to): history of ischaemic heart disease or heart failure, stroke or transient ischaemic attack, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease≥3 grade GOLD (Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease) and end stage renal disease undergoing dialysis], or any other clinical or intervention-related condition at the discretion of the anesthesiologist.

Whether the “natural” evolution of standards of care contemporary with introduction of ERALS programs, such as the use of VATS and promotion of early mobilization, alone explains the improvement in outcomes remains a matter of debate.2,13,31,32 Several authors have reported that greater compliance with ERALS programs is associated with better results, indicating that the different variables involved in these pathways potentially have a summative effect.5,7 However, although global compliance with ERALS protocols has been identified as having influenced outcomes, only some specific aspects of these protocols have been shown to be independent predictors of outcomes.3,5,7 Forster et al. reported that early removal of chest tubes, use of electronic drainage systems, cessation of opioids on POD 3, and early feeding are independently associated with a reduction in rate of complications.7 As these authors have pointed out, which variables are included in multivariable analysis “can lead to a misinterpretation of the results”; for example, does either an early withdrawal of chest drainage or discontinuation of opioids reflect a protective effect on POC, or do they simply reflect that the patient is in better condition? Rogers et al. have shown that global compliance predicts POC but not POS, the latter showing independent correlations with early mobilization, preoperative carbohydrate-rich drinks, and implementation of VATS.5 We are therefore uncertain whether we should direct our efforts to improving outcomes by implementing a global strategy based on the summative effect of marginal gains, each with its specific cost, or focus on enhancing aspects that have been identified as independent predictors of outcomes. Our uncertainty is compounded by the fact that some of the main factors influencing POS, such as management of air leaks, are not exclusively ERALS but also depend on culture and organization.13,29,33 As pointed out by other authors, “management of chest tubes remains a critical aspect in the postoperative course of patients following lung resection”.20 We observed a non-negligible number of drains not removed after ceasing the air leak, this reflecting the everyday practice versus the stablished ERALS criteria, and moreover probably influencing our improvable POS. Whether a more aggressive withdrawal policy following the published recommendations9 would have had an impact on our results is something that should be addressed in coming works.

The main shortcoming of our study is its retrospective nature and the potential risk of having underestimated the incidence of the selected factors. Our data were drawn from a single center with specific conditions; thus, our results are not necessarily applicable to other healthcare providers. Another shortcoming of our work was the exclusion of preoperative components of the ERALS program from the analysis. Indeed, some relevant aspects of the ERALS programs, as preoperative carbohydrate-rich drinks, had not yet been incorporated into our protocol and therefore not analyzed. This latter reflecting the heterogeneity previously described when implementing ERALS pathways.6,10

As other authors point out, the inclusion of patients undergoing surgery over a period where minimally invasive techniques were being used to varying degrees may introduce substantial bias, as the increased use of VATS or the cultural transformation towards a more proactive attitude may have influenced the results.32 In this sense, it is likely that over the 8 years included in the analysis the management of these patients regardless of ERALS protocols has been streamlined.

Despite these limitations, we demonstrated the feasibility of incorporating an ERALS protocol in our institution, with statistics of POS and ICU admissions that improve our historical figures. We have shown that, even in the presence of various limitations to implementing an ERALS protocol in a Spanish public center, the results obtained support this practice.

ConclusionsWe observed a reduction in ICU admissions and POS contemporaneous with the use of an ERALS program in our institution. We demonstrated that mobilization in the first 24h after surgery and VATS approach are modifiable independent predictors for the reduction of POC and POS, respectively. New prospective and well-designed studies are needed to address the impacts of the overall performance of an ERALS program versus the impacts of improvement in specific elements of special relevance, to identify the crucial factors.

Funding sourcesThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We thank Dr. Trish Reynolds, MBBS, FRACP, from Edanz Group (https://en-author-services.edanzgroup.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.