Outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a safe procedure and provides a better use of health resources and perceived satisfaction without affecting quality of care. Preoperative education has shown less postoperative stress, pain and nausea in some interventions. The principal objective of this study is to assess the impact of preoperative education on postoperative pain in patients undergoing ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Secondary objectives were: to evaluate presence of nausea, morbidity, hospital admissions, readmissions rate, quality of life and satisfaction.

MethodsProspective, randomized, and double blind study. Between April 2014 and May 2016, 62 patients underwent outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Inclusion criteriaASA I-II, age 18–75, outpatient surgery criteria, abdominal ultrasonography with cholelithiasis. Patient randomization in two groups, group A: intensified preoperative education and group B: control.

ResultsSixty-two patients included, 44 women (71%), 18 men (29%), mean age 46.8 years (20–69). Mean BMI 27.5. Outpatient rate 92%. Five cases required admission, two due to nausea. Pain scores obtained using a VAS was at 24-hour, 2.9 in group A and 2.7 in group B. There were no severe complications or readmissions. Results of satisfaction and quality of life scores were similar for both groups.

ConclusionsWe did not find differences due to intensive preoperative education. However, we think that a correct information protocol should be integrated into the patient's preoperative preparation.

Registered in ISRCTN number ISRCTN83787412.

La colecistectomía laparoscópica ambulatoria es segura y proporciona mejor aprovechamiento de recursos sanitarios y satisfacción percibida, sin repercutir en la calidad asistencial. La educación preoperatoria ha demostrado disminución del estrés, del dolor y náuseas postoperatorios en algunas intervenciones. El objetivo principal del estudio es valorar el impacto de la educación preoperatoria sobre el dolor postoperatorio en la colecistectomía laparoscópica ambulatoria. Los objetivos secundarios fueron evaluar las náuseas postoperatorias, morbilidad, ingresos no esperados, readmisiones, calidad de vida y grado de satisfacción.

MétodosEstudio prospectivo, aleatorizado, doble ciego. Entre abril de 2014 y mayo de 2016 fueron intervenidos 62 pacientes de colecistectomía laparoscópica ambulatoria.

Criterios de inclusiónASA I-II, edad 18-75 años, criterios de ambulatorización, ecografía abdominal con colelitiasis. Aleatorización de pacientes en grupo A: educación preoperatoria intensificada, y grupo B: control.

ResultadosSesenta y dos pacientes incluidos, 44 mujeres (71%), 18 hombres (29%), edad media 46,8 años (20-69). Media IMC de 27,5. Tasa de ambulatorización del 92%, 5 casos requirieron ingreso, 2 fueron por náuseas. La media del grado de dolor según EVA fue a las 24h de 2,9 en el grupo A y de 2,7 en el grupo B. No complicaciones graves ni reingresos. La encuesta de satisfacción y el test de calidad de vida no mostraron diferencias entre grupos.

ConclusionesLas bajas cifras de dolor y complicaciones impiden evidenciar diferencias atribuibles a la educación preoperatoria. Sin embargo, un correcto protocolo de información se debería integrar en la preparación preoperatoria de los pacientes.

Registro ISRCTN con número de referencia ISRCTN83787412.

The surgical treatment of cholelithiasis has traditionally been a procedure performed in hospitalized patients. The introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy radically changed the treatment of this disease and is now considered the gold standard for benign gallbladder disease.1 Several prospective randomized studies have demonstrated the advantages of laparoscopic surgery: less pain and postoperative paralytic ileus, shorter hospital stay, early return to daily activity and decrease in total procedure costs.2–7 All these factors have allowed for laparoscopic cholecystectomy to be progressively incorporated into short-stay and major outpatient surgery (MOS) programs.

According to the results of the first published study on ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy in 1990 by Reddick and Olsen,8 45% of patients could be treated in an MOS regimen with minimal complications, especially young patients without a history of abdominal surgery.

Several studies have subsequently shown that ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a safe technique offering a high degree of patient satisfaction and perceived quality.9–14

However, a high proportion of unexpected hospitalizations (37%)15 have been attributed to the onset of nausea and pain in the immediate postoperative period.

The first ever research about the benefits of preoperative education was published in 1958 (Janis),16 demonstrating that preoperative information reduces patient stress. Other studies have revealed that patients who have received preoperative information require less analgesia and recover faster.17

Our hypothesis is that the patients who receive preoperative education, as they are informed about the surgical and anesthetic procedure as well as the symptoms that may appear in the postoperative period, experience a lower degree of anxiety generated by the procedure, which helps to better control symptoms and recovery in the outpatient surgery regimen, while increasing the level of satisfaction.

The main objective of this study is to assess the impact of patient preoperative education and its effect on pain. The secondary objectives were to evaluate the appearance of nausea, unexpected hospitalizations, readmissions, intra- and postoperative morbidity, quality of life and the degree of satisfaction in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the outpatient setting.

MethodsStudy DesignThis prospective, randomized, double-blind study was conducted at the Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII in Tarragona (Spain) between April 2014 and May 2016.

The project was approved by the hospital's Ethics Committee and was conducted in accordance with the guidelines for proper clinical practice of the Declaration of Helsinki and the CONSORT statement. The study was registered with the ISRCTN registry (reference number ISRCTN83787412).

Included in the study were patients who had been consecutively proposed for laparoscopic cholecystectomy and met the inclusion criteria but none of the exclusion criteria for outpatient treatment. Patients freely agreed to participate in the study and gave their written consent.

Patients were randomized into 2 groups, according to a spreadsheet electronically designed by the hospital's Statistical Department. In addition to the standard information provided by their surgeon, the group with intensified preoperative education (A) received personalized oral and written information (informative brochure) of the entire surgical and anesthetic process from a specialized nurse. The group of patients with standard information (B) received the conventional oral information from the surgeon at the office visit.

The surgeon, patients and study monitor were unaware of which group each patient belonged to.

Inclusion Criteria- -

ASA I, II;

- -

Age 18–75 yrs;

- -

MOS criteria: proximity to the hospital <30min, social support (lives with others), possibility to communicate by phone at the residence;

- -

Patient acceptance of outpatient surgery;

- -

Symptomatic cholelithiasis with diagnostic abdominal ultrasound;

- -

No history of choledocholithiasis;

- -

No previous abdominal surgery.

- -

ASA III–IV;

- -

MOS criteria not met;

- -

Language difficulty or lack of comprehension of the information;

- -

Difficult airway and comorbidity, such as patients with kidney failure being treated with dialysis, congestive heart failure, coagulation alterations or obesity.

The included patients were scheduled for office visits in the outpatient surgery consultation, where the surgical intervention was explained and they were given an information sheet about the study. Patients also signed the informed consent for the procedure and MOS, and they answered the SF-12 quality of life test (12-item Short-Form Health Survey), in which 8 aspects of health are evaluated: physical function, physical role, emotional role, social function, mental health, general health, physical pain and vitality.18,19

Between 2 and 4 weeks after the visit with the surgeon, patients had appointments with the specialized nurse, who was previously trained in the information about the following points of the process: type of operation, symptoms to be treated in the postoperative period, probable complications, wound care and diet. This day, the preoperative studies, randomization and assignment of each patient to one of the 2 study groups was carried out.

Surgery was scheduled for 15–30 days after the visit with the specialized nurse.

All patients underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy under the previously established MOS protocol.

Conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed with all patients in the French position, using 3 trocars and a CO2 pressure below 12mmHg. Levobupivacaine 0.5% was infiltrated in the trocar incisions at the beginning of the surgery, and 20mg of 0.5% intraperitoneal ropivacaine was instilled at the end. The trocars were withdrawn under direct vision along with withdrawal of all the pneumoperitoneum. Drain tubes were not placed in any of the patients.

After surgery, the degree of pain as well as anesthesia-related nausea and vomiting were assessed using the visual analog scale (VAS) 2, 4 and 6h after surgery. Oral intake of liquids was initiated 2h post-op.

When the patient did not present nausea or vomiting and their pain was controlled, together with a score higher than 9 in the Aldrete criteria,20 the patient was discharged from hospital.

Unexpected hospitalization patients were defined as those patients in whom the outpatient process could not be completed.

Twenty-four hours later, the patients were followed-up by the Home Hospitalization Unit, and patients were scheduled for follow-up office visits on postoperative days 7 and 30.

Epidemiological variables, presence of nausea or vomiting and postoperative pain were analyzed 24h, 7 days and 30 days after surgery using VAS and intra- and postoperative morbidity, with postoperative complications ranked according to Clavien Dindo classification.21

We also analyzed the rate of unexpected hospitalizations, readmissions, time until resuming normal and work activities, quality of life measured by the SF-12 test on post-op day 30, and patient satisfaction as evaluated by a questionnaire.

Statistical AnalysisConsidering a level of significance of 95% and a power required for the study of 80%, with bilateral contrast and assuming a 5% loss to follow-up during the study period, we calculated a minimum necessary sample size of 62 individuals (31 in each group).

The results were recorded in a database specifically designed for this study and analyzed with SPSS v16 software.

In this study, we conducted a descriptive analysis of all the study variables, a correlation analysis between the quantitative variables studied and a comparative analysis of the variables of interest for each group. In the comparative analysis, specific techniques were used according to the type of data: parametric tests (Pearson's R, Student's t test) and nonparametric tests (Chi squared, Spearman's R, Mann–Whitney's U).

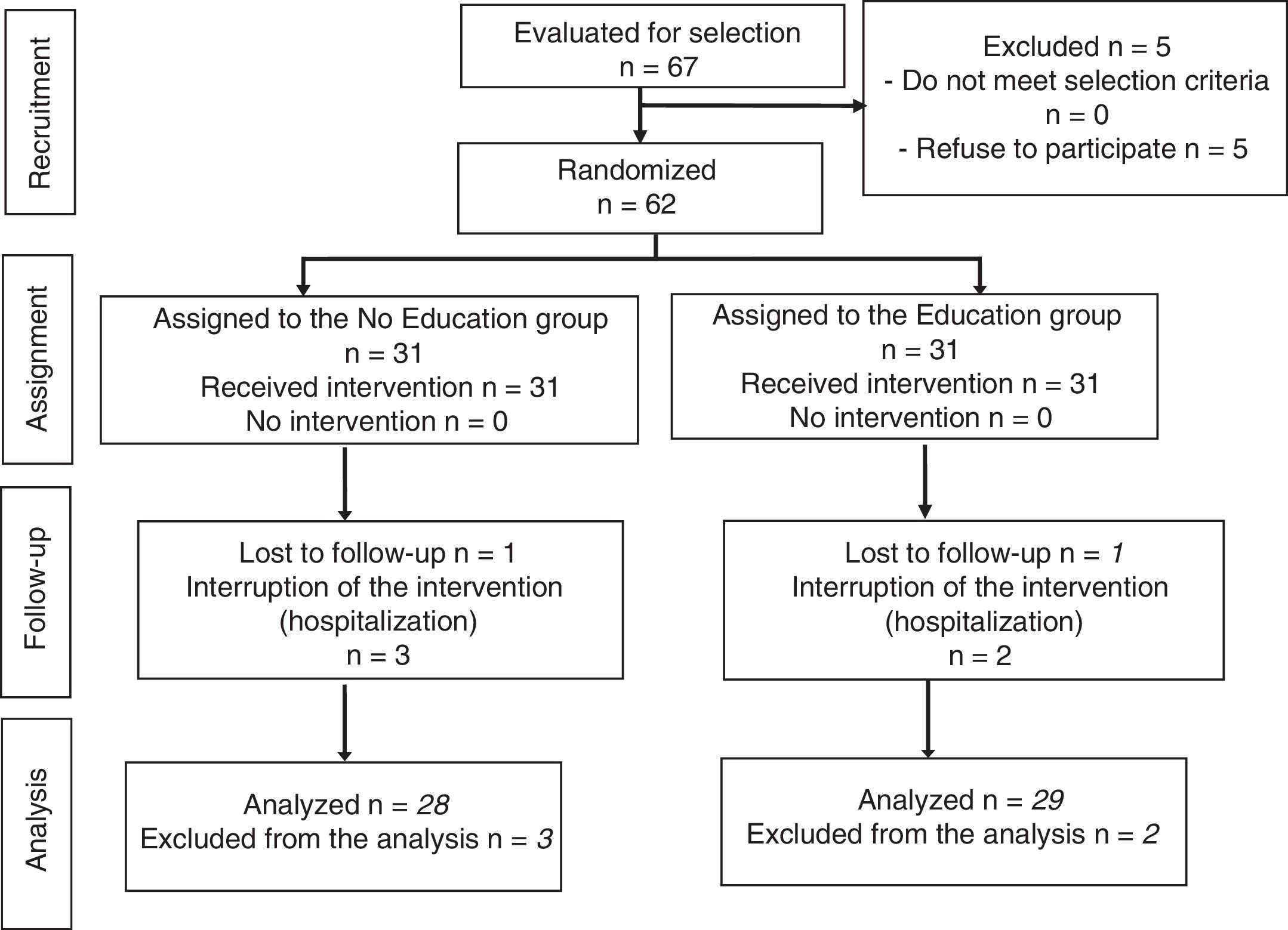

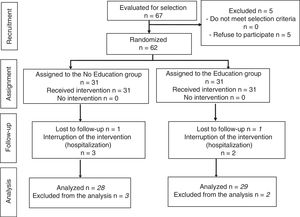

ResultsThe study population consisted of 62 patients who underwent outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The process of patient selection and inclusion is documented in the Consort flow diagram in Fig. 1.

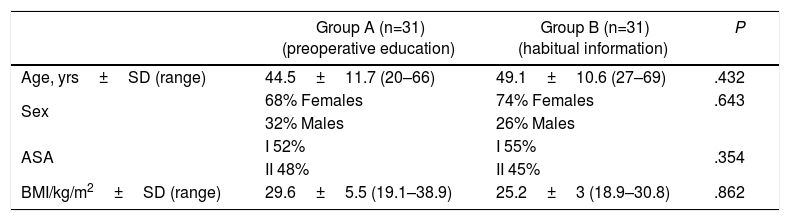

71% of the patients were women (n=44) and 29% were men (n=18), with a mean age of 46.8±11.5 years (20–69) and a mean BMI of 27.5±4 (18.9–39). More than half of the patients were considered ASA I, and the average number of days on the surgical waiting list was 38. The groups proved to be homogeneous for the demographic variables analyzed (Table 1).

Epidemiological Results (Total n=62).

| Group A (n=31) (preoperative education) | Group B (n=31) (habitual information) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs±SD (range) | 44.5±11.7 (20–66) | 49.1±10.6 (27–69) | .432 |

| Sex | 68% Females | 74% Females | .643 |

| 32% Males | 26% Males | ||

| ASA | I 52% | I 55% | .354 |

| II 48% | II 45% | ||

| BMI/kg/m2±SD (range) | 29.6±5.5 (19.1–38.9) | 25.2±3 (18.9–30.8) | .862 |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI: body mass index.

The operative time was less than 90min in all cases, and all procedures were completed laparoscopically. Two patients required the placement of an additional trocar because of difficult exposure.

The outpatient management rate was 92% (57 patients). Five patients required unexpected hospital admission, 2 of them due to nausea (one in each group) and 3 due to intraoperative findings (one case of acute cholecystitis in group A and 2 cases of empyema of the gallbladder in the control group).

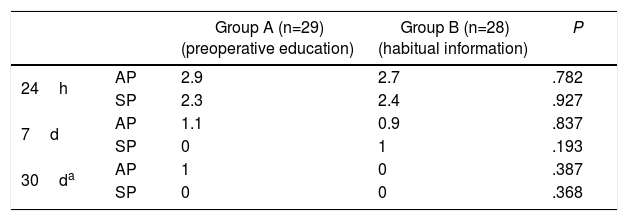

With regard to the evaluation of postoperative pain, the mean VAS scores were as follows: abdominal pain after 24h of 2.9 in group A and 2.7 in group B, and subscapular pain after 24h of 2.3 and 2.4, respectively. One week and one month after the intervention, mean abdominal and subscapular pain was less than 1 in both groups (Table 2).

Evaluation of Postoperative Pain.

| Group A (n=29) (preoperative education) | Group B (n=28) (habitual information) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24h | AP | 2.9 | 2.7 | .782 |

| SP | 2.3 | 2.4 | .927 | |

| 7d | AP | 1.1 | 0.9 | .837 |

| SP | 0 | 1 | .193 | |

| 30da | AP | 1 | 0 | .387 |

| SP | 0 | 0 | .368 |

AP: abdominal pain; SP: subscapular pain.

Utilizing the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS); values are means.

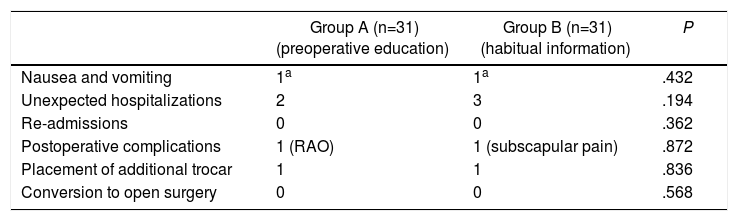

No major intraoperative or postoperative complications were recorded according to the Clavien Dindo classification, although 2 patients required attention in the emergency room 24h after surgery, one due to subscapular pain and the other due to acute urinary retention, both of whom were discharged. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in terms of postoperative complications and no readmissions were recorded after hospital discharge (Table 3).

Results of the Secondary Objectives (total n=62).

| Group A (n=31) (preoperative education) | Group B (n=31) (habitual information) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nausea and vomiting | 1a | 1a | .432 |

| Unexpected hospitalizations | 2 | 3 | .194 |

| Re-admissions | 0 | 0 | .362 |

| Postoperative complications | 1 (RAO) | 1 (subscapular pain) | .872 |

| Placement of additional trocar | 1 | 1 | .836 |

| Conversion to open surgery | 0 | 0 | .568 |

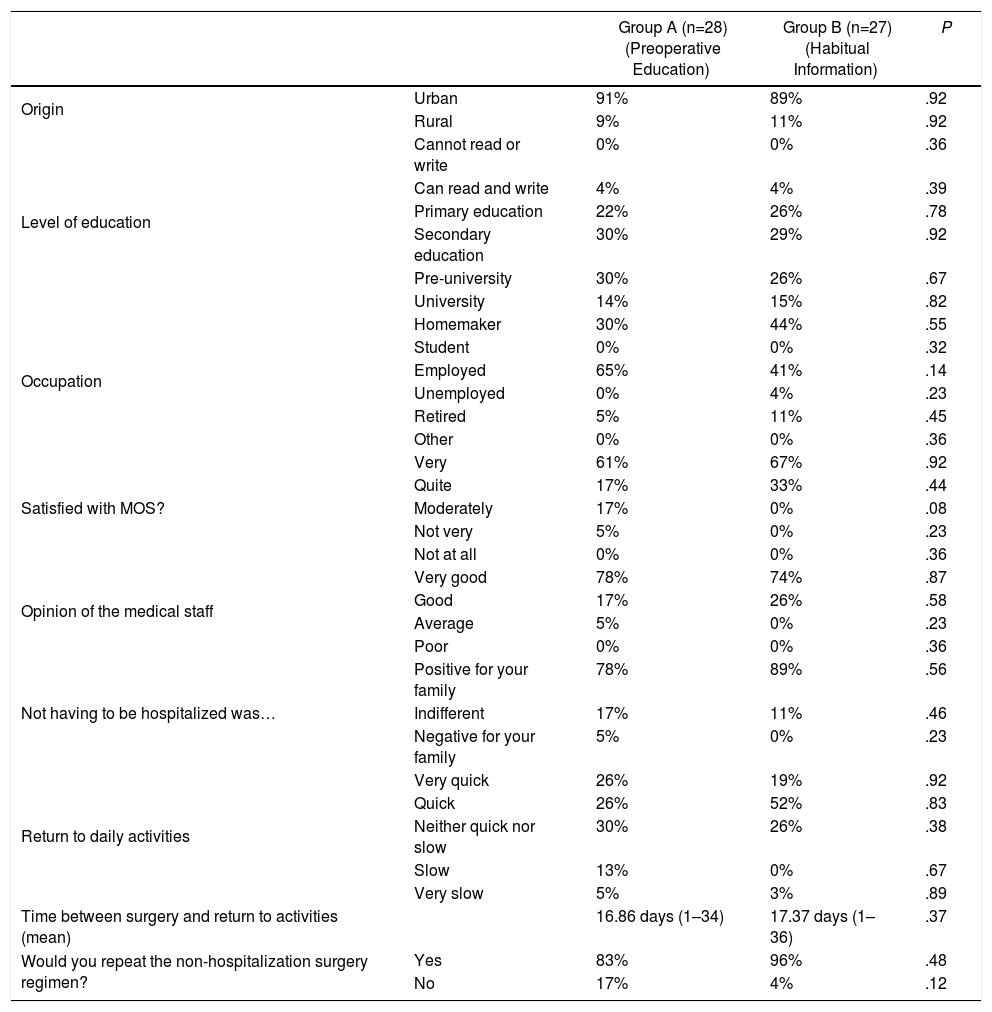

The results of the satisfaction survey are shown in Table 4, with no observed statistically significant differences between the two groups. 98% of the patients considered that they were thoroughly explained what the ambulatory surgery consisted of.

Results From Satisfaction Questionnaire.

| Group A (n=28) (Preoperative Education) | Group B (n=27) (Habitual Information) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | Urban | 91% | 89% | .92 |

| Rural | 9% | 11% | .92 | |

| Level of education | Cannot read or write | 0% | 0% | .36 |

| Can read and write | 4% | 4% | .39 | |

| Primary education | 22% | 26% | .78 | |

| Secondary education | 30% | 29% | .92 | |

| Pre-university | 30% | 26% | .67 | |

| University | 14% | 15% | .82 | |

| Occupation | Homemaker | 30% | 44% | .55 |

| Student | 0% | 0% | .32 | |

| Employed | 65% | 41% | .14 | |

| Unemployed | 0% | 4% | .23 | |

| Retired | 5% | 11% | .45 | |

| Other | 0% | 0% | .36 | |

| Satisfied with MOS? | Very | 61% | 67% | .92 |

| Quite | 17% | 33% | .44 | |

| Moderately | 17% | 0% | .08 | |

| Not very | 5% | 0% | .23 | |

| Not at all | 0% | 0% | .36 | |

| Opinion of the medical staff | Very good | 78% | 74% | .87 |

| Good | 17% | 26% | .58 | |

| Average | 5% | 0% | .23 | |

| Poor | 0% | 0% | .36 | |

| Not having to be hospitalized was… | Positive for your family | 78% | 89% | .56 |

| Indifferent | 17% | 11% | .46 | |

| Negative for your family | 5% | 0% | .23 | |

| Return to daily activities | Very quick | 26% | 19% | .92 |

| Quick | 26% | 52% | .83 | |

| Neither quick nor slow | 30% | 26% | .38 | |

| Slow | 13% | 0% | .67 | |

| Very slow | 5% | 3% | .89 | |

| Time between surgery and return to activities (mean) | 16.86 days (1–34) | 17.37 days (1–36) | .37 | |

| Would you repeat the non-hospitalization surgery regimen? | Yes | 83% | 96% | .48 |

| No | 17% | 4% | .12 |

The survey was taken on postoperative day 30, and at that time 2 patients were lost to follow-up.

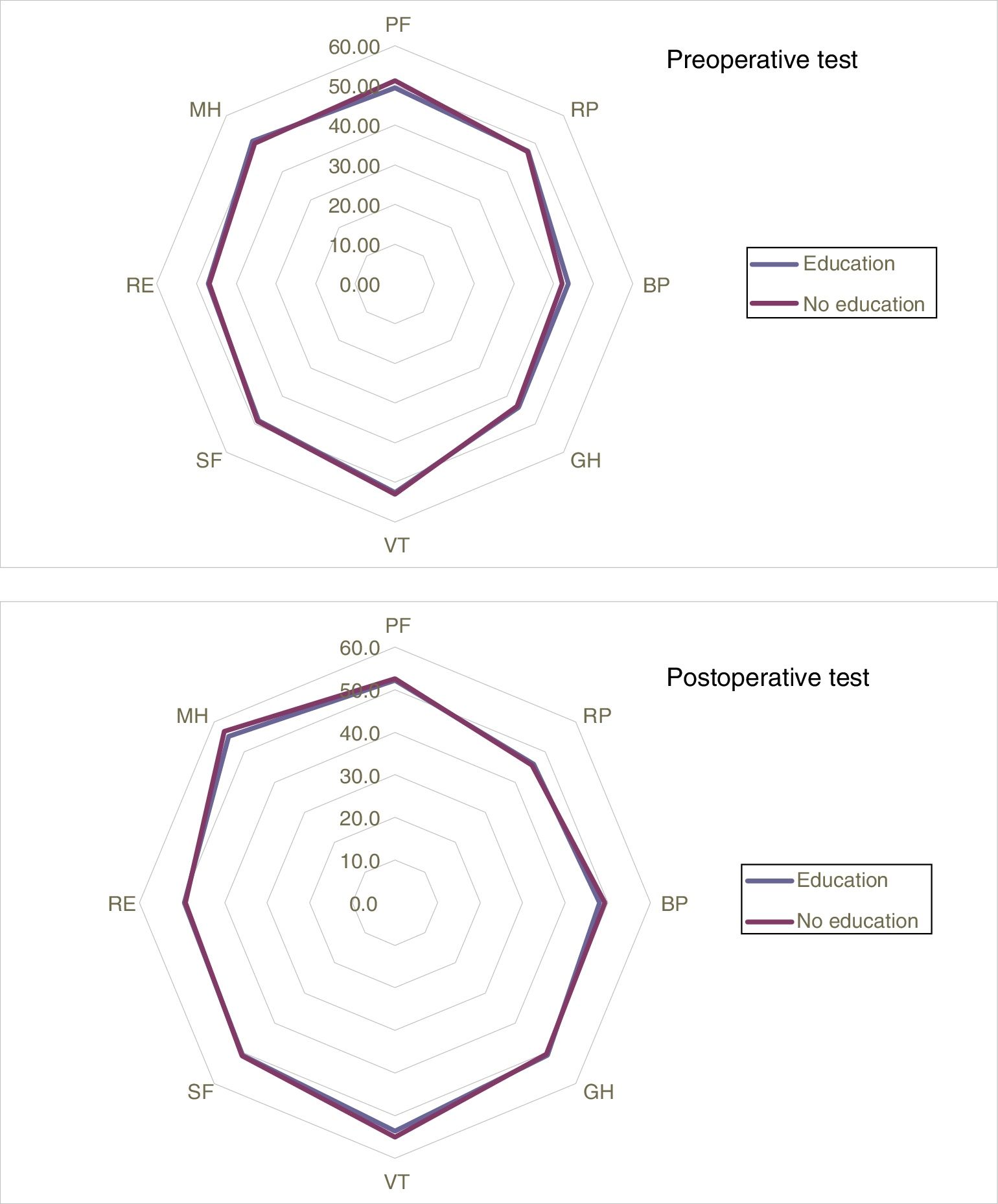

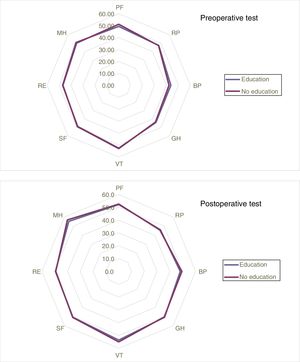

Likewise, no statistically significant differences were found between the pre- and postoperative results of the SF-12 test, regardless of the preoperative education received (Fig. 2), but there was improvement in the results in the General Health and Mental Health domains of the postoperative test compared to the preoperative test in both groups.

Results of the pre- and postoperative SF-12 test, where there were no statistically significant differences in the 8 domains evaluated

BP: bodily pain; GH: general health; MH: mental health; PF: physical function; RE: role limitations – emotional; RP: role limitations – physical; SF: social functioning; VT: vitality.

MOS has been developed thanks to advances in anesthetic and surgical techniques as well as extra-hospital support techniques.22 In the process of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, MOS reduces costs without affecting the quality of care.

A randomized study by Aguilar-Nascimiento et al.23 demonstrated in open cholecystectomy that detailed verbal and written information was associated with less intense nausea and postoperative pain.

Blay et al.24 demonstrated that patients who received preoperative information required less analgesia and recovered more quickly. Meanwhile, Costa25 correlated the presence of postoperative pain and fatigue with lack of information and inadequate preoperative preparation. More information gave patients more autonomy and control over the postoperative symptoms and wound management after hospital discharge.

Thus, intensified preoperative education, compared to the habitual information, can promote positive postoperative results in surgical patients.26

There have been studies in which preoperative education and information are supported with multimedia tools. Despite not finding significant differences in the degree of postoperative pain, the authors considered that, although the additional information may be of great help in understanding the procedure, it cannot replace patient-surgeon personal dialogue.27–29

In the Cochrane review by Gurusamy et al.,30 the authors wanted to evaluate the benefits of preoperative education for patients undergoing cholecystectomy. None of the included studies reported results on morbidity, quality of life or MOS. No clear evidence was found of the effect of preoperative education on patient knowledge, satisfaction or anxiety. Along with the studies published to date, this affirms that preoperative education still has uncertain results compared with the usual information.31

In our study, no significant differences were found in terms of pain levels or postoperative nausea, morbidity, percentage of unexpected hospitalizations, quality of life or degree of satisfaction. Perhaps these results are due to a small sample size, which could be considered a study limitation.

A high rate of ambulatory treatment was achieved (92%), which could be attributed to the intensified preoperative education, as the patient feels more secure with more information, although there were no differences between groups.

Shorter waiting list times and hospital stays result in greater patient acceptance and satisfaction, as measured by the satisfaction questionnaires.

Improved health status, optimal treatment and services offered are factors that patients appreciate the most.32

In our study, the mean number of days on the waiting list was 38, which is why most patients felt satisfied with the process. The mean number of days transpired between surgery and the return to everyday activities was 17; most patients perceived their return to normal daily activities as quick, which we believe also contributed to the increased patient satisfaction and consequently the number of patients who would repeat the process.

Although no statistically significant differences were found between the pre- and postoperative results of the SF-12 test in terms of the preoperative education received, there was an improvement in the results in the domains of General Health and Mental Health in the postoperative test compared to the preoperative results in both groups. We assume that this was associated with the improvement of symptoms.

Another aspect to be highlighted was the perception that surgery without admission provides greater advantages for the family or caregivers, as declared by 84% of patients.

After the results of this study, we still believe in the importance of preoperative education before each procedure. However, in the case of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, adequate information from the surgeon and anesthesiologist may be sufficient, as no significant differences were found when adding intensified education by skilled nursing staff. Most likely, the fact that laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a very frequent procedure means that the majority of patients come to the consultation already informed by other means (other patients, media, etc.) and already have a prior perception that the results of the intervention will be favorable, which reduces anxiety and concerns about the intervention.

In conclusion, outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a safe technique that provides rapid recovery. The low pain figures reported in the 2 groups prevent the detection of differences due to preoperative education. However, we believe that a proper information protocol should be integrated into the preoperative preparation of patients, as it may result in improved patient satisfaction.

Authorship- -

Helena Subirana Magdaleno: data collection, article composition;

- -

Aleidis Caro Tarragó: study design, data collection, critical review;

- -

Carles Olona Casas: study design, analysis and interpretation of the study;

- -

Alba Díaz Padillo: data collection, analysis and interpretation of the study;

- -

Mario Franco Chacón: data collection, analysis and interpretation of the study;

- -

Jordi Vadillo Bargalló: analysis and interpretation of the study, critical review;

- -

Judit Saludes Serra: data collection, analysis and interpretation of the study, critical review;

- -

Rosa Jorba Martín: study design, critical review and approval of the final version.

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Subirana Magdaleno H, Caro Tarragó A, Olona Casas C, Díaz Padillo A, Franco Chacón M, Vadillo Bargalló J, et al. Valoración del impacto de la educación preoperatoria en la colecistectomía laparoscópica ambulatoria. Ensayo prospectivo aleatorizado doble ciego. Cir Esp. 2018;96:88–95.

The study was presented as an oral communication at the 23rd Surgery Symposium of the Hospitals of Catalonia on October 14, 2016.