Severe pharyngeal stenosis occurs in 0.7%–6% of patients after the ingestion of caustic substances.1 These injuries are usually the result of massive ingestion of corrosive agents. In this context, restoring digestive tract continuity frequently involves the need to reconstruct the esophagus and the pharynx simultaneously, therefore requiring longer plasties with an elevated risk of ischemia and anastomotic dehiscence. Colopharyngoplasty, which may also be associated with laryngectomy, is a technique that has been used in these cases to reconstruct the esophagus and pharynx.1,2 Intraoperative verification of the viability of the plasty with indocyanine green (ICG) fluorescence imaging can be useful to ensure the success of this surgery.

We present 2 cases in which colopharyngoplasty was conducted to reconstruct the digestive tract after esophagogastric resection due to the ingestion of a caustic substance. Afterwards, intravenous ICG was used to assess the perfusion of the plasty.

Case 1In June 2012, a 35-year-old man came to the emergency room after having ingested hydrochloric acid in a deliberate act of self-harm. Urgent surgery was performed with total esophagogastrectomy, cervical esophagostomy and feeding jejunostomy. The postoperative period was complex, and the patient was finally discharged 2 months later. In February 2013, reconstruction surgery was attempted, which failed due to complete stenosis of the esophageal remnant. In August 2015, another attempt at reconstruction was made with the otorhinolaryngology team. Colopharyngoplasty was performed with isoperistaltic right colon. During surgery, viability of the plasty was confirmed by fluorescence angiography. The patient was administered 1 cc of intravenous ICG (solution: 25mg of ICG in 10mL of sterile water) and checked 60s after administration. This was repeated once the plasty was placed in its final retrosternal position. Correct perfusion of the area for anastomosis was corroborated, and manual end-to-side anastomosis was created with absorbable interrupted stitches in a single layer. The postoperative period transpired with no major incidents, and the patient was discharged a month later.

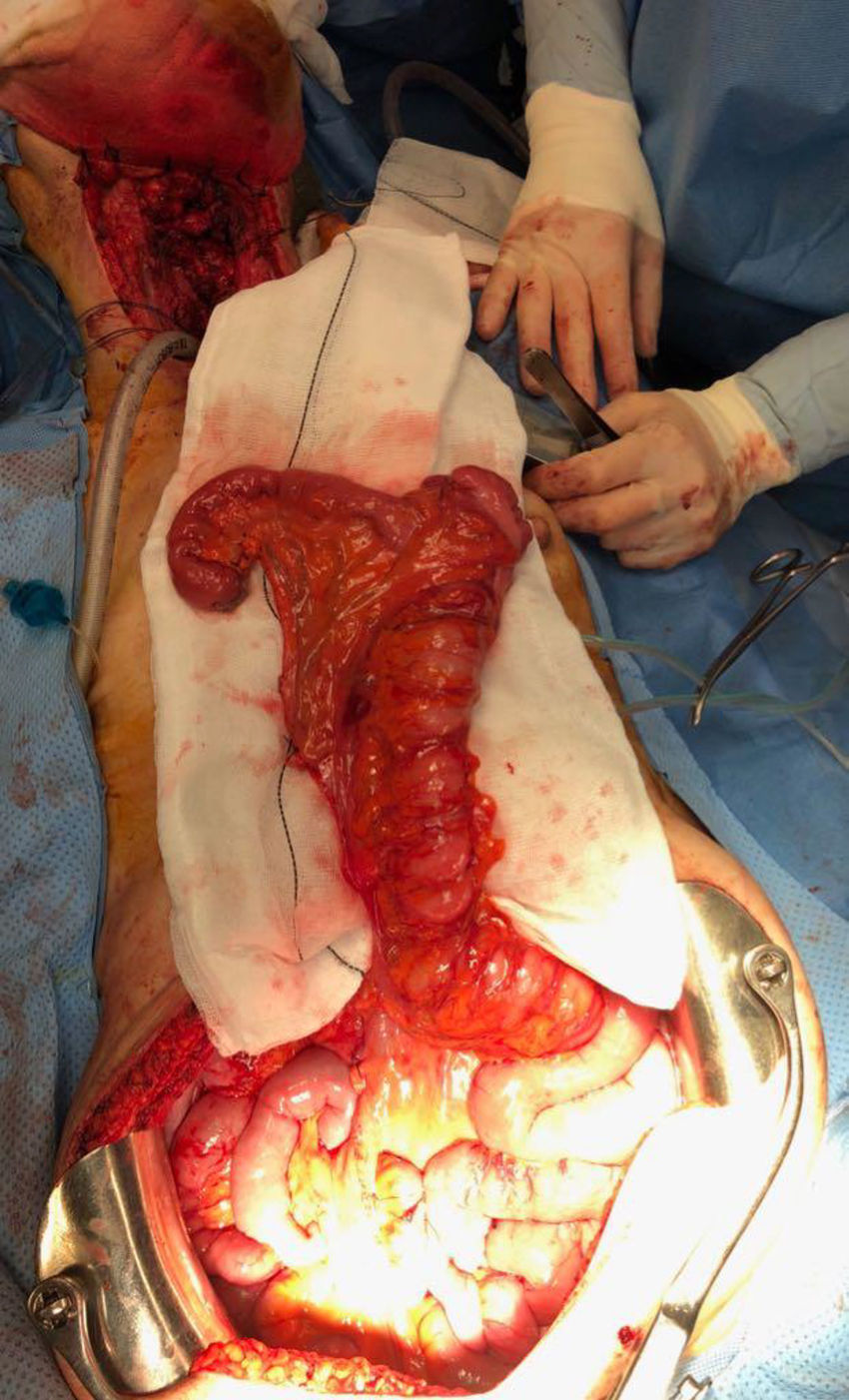

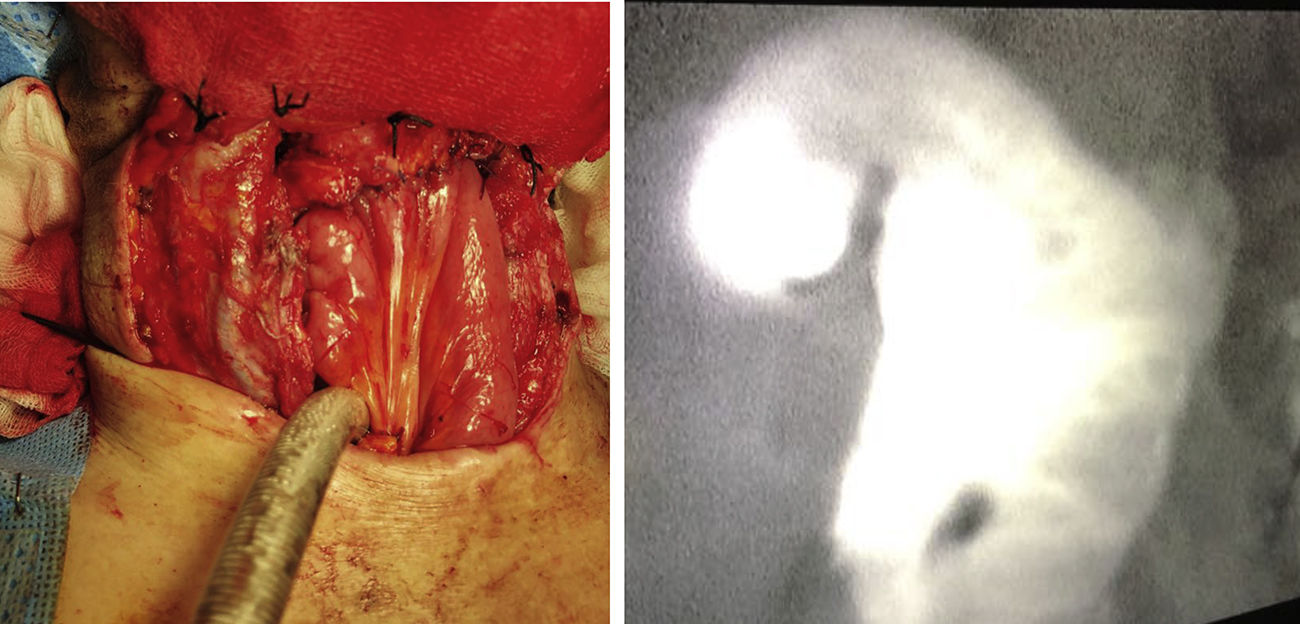

Case 2After ingesting caustic substances with the purpose of self-injury, a 47-year-old woman underwent total esophagogastrectomy, terminal pharyngostomy, tracheostomy, and feeding jejunostomy in December 2008. In May 2018, after several hospitalizations for severe aspiration pneumonia, the patient was admitted for laryngectomy and reconstruction of the digestive tract. Laryngeal resection, terminal tracheostomy and colopharyngoplasty were performed with the right colon (Fig. 1). The viability of the plasty was confirmed with ICG using the same methodology as in case 1 (Fig. 2), and a manual end-to-side pharyngo-ileal anastomosis was created. On the fourth postoperative day, the patient presented with a low-output salivary gland fistula, which was resolved with conservative treatment. The patient was discharged one month after the intervention.

Massive ingestion of caustic agents sometimes causes considerable esophagogastric necrosis requiring extensive resections to avoid patient death. There is often involvement of the hypopharynx, which makes reconstruction challenging as it presents 2 additional difficulties: the altered swallowing/breathing mechanism; and the need for a longer plasty, with the subsequent increased risk of necrosis. The intravenous injection of ICG for the assessment of vascularization is now a fast, reproducible and safe technique that has become popular especially in plastic surgery for the intraoperative assessment of the viability of pedicle or free flaps.3 It is based on the capacity of this water-soluble compound for the fixation to proteins of the blood or tissue and the emission of an infrared light between 750 and 810nm with a plasma half-life of 3–5min, which provides an excellent level of safety and the possibility to repeat the test within a short time. In digestive tract surgery, fluorescence imaging with ICG has been used in colorectal procedures to assess the viability of the colon, and it could also play a role in reducing anastomotic dehiscence rates.4,5 In esophageal surgery, it has been used for the intraoperative evaluation of gastric plasty perfusion.6 Kumagai et al.7 have even determined the perfusion time of ICG from the root of the gastroepiploic artery to the end of the gastric graft to predict the optimal site of the anastomosis and thus ensure its success, establishing that it should be less than 90s.

In the reconstruction of the digestive tract in cases of massive intake of corrosive agents, several factors must be considered: the location and length of the stenosis, the degree of involvement of the pharynx and larynx, vocal cord function, the existence of tracheostomy prior to reconstruction, previous gastric resection, and the nutritional/psychiatric status of the patient. In patients with gastric resection and pharyngeal involvement, the length and excellent vascularization of the colon make it a perfect substitute, especially in cases of upper pharyngeal stenosis.

Even so, these are long plasties that have to be pulled up retrosternally because the posterior mediastinum is not feasible in patients with similar medical histories. In these cases, the use of intraoperative ICG can be especially useful to ensure the viability of a plasty that has a high risk of failure.

Please cite this article as: Garsot Savall E, Viciano Martín M, Sastre Papiol JM, Pollán Guisasola C, Julián Ibáñez JF. Utilidad de la angiografía con fluorescencia para la comprobación de la viabilidad de la plastia de colon en el proceso de reconstrucción del tránsito digestivo tras ingesta masiva de cáusticos. Cir Esp. 2019;97:297–299.