The appearance of a diaphragmatic hernia after esophagectomy is a very rare complication. These hernias are usually asymptomatic and are diagnosed during follow-up imaging tests. When they occur, symptoms include dysphagia, reflux, vomiting or weight loss. However, there are no reports in the literature of life-threatening complications, such as the presence of obstructive shock secondary to cardiac tamponade associated with respiratory failure due to atelectasis.

We report the case of a 54-year-old man who was treated surgically for esophagogastric junction cancer, involving laparoscopic and thoracoscopic esophagectomy with transthoracic gastric pull-up to the cervical region following the McKeown technique, requiring resection of some muscle fibers on the left side of the esophageal hiatus due to tumor involvement. Eight months later, he came to the emergency department due to dyspnea on moderate exertion and epigastric pain over the previous 48 h.

Physical examination revealed tachypnea (30 breaths/min), baseline saturation 94%, bp 90/50 mmHg, and heart rate 130 bpm. Auscultation revealed hypoventilation in the entire left hemithorax, while abdominal palpation showed no signs of peritoneal irritation.

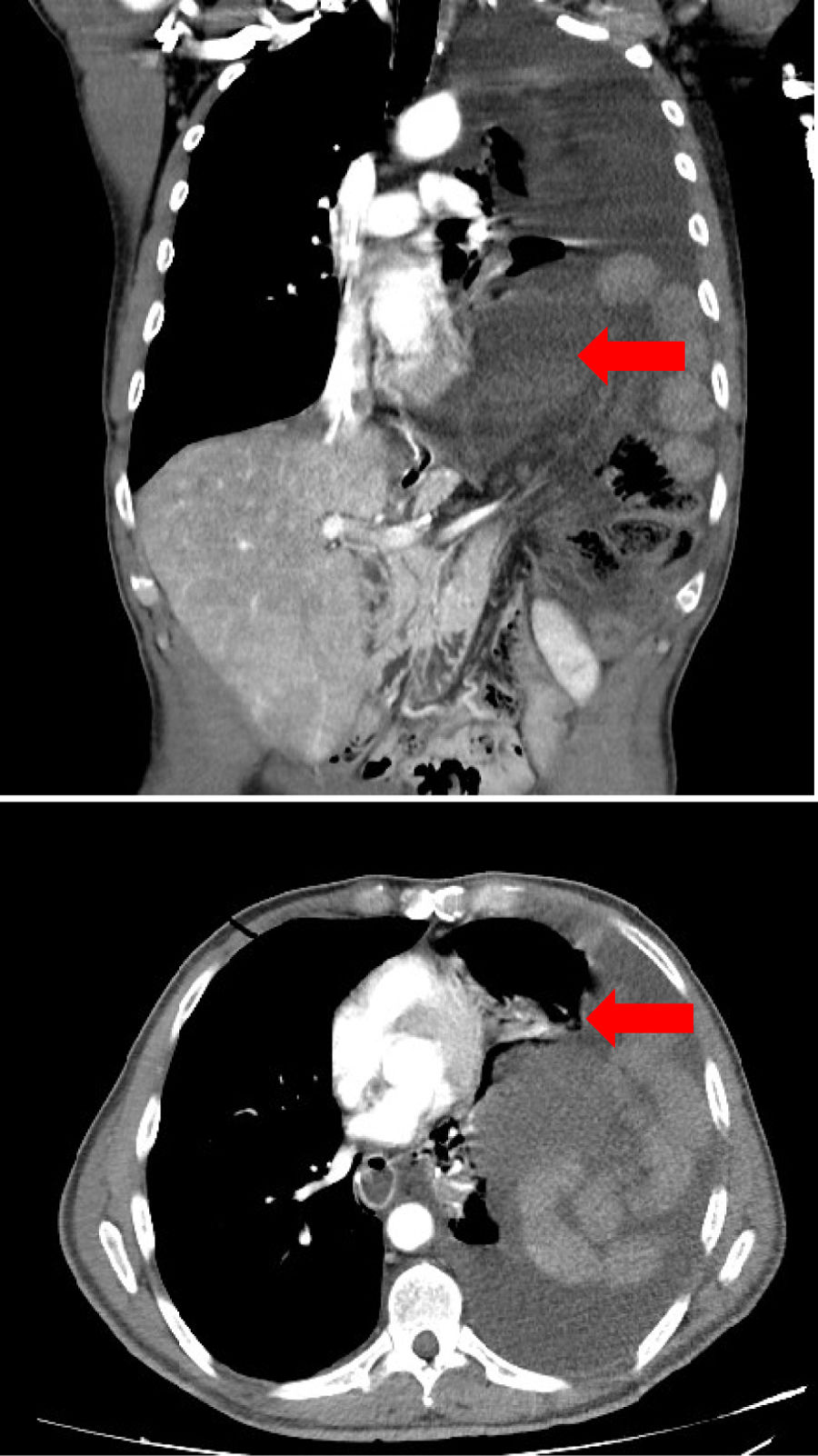

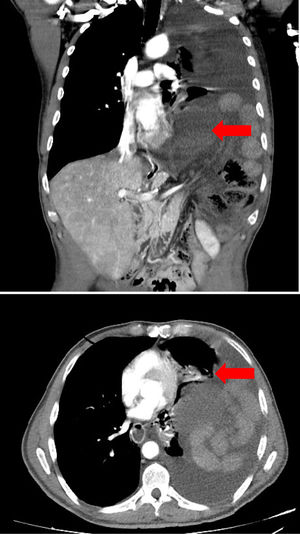

Lab work showed 18,000 leukocytes and a C-reactive protein of 3 mg/dL. Thoracoabdominal computed tomography (Fig. 1) identified a large hernia in the left hemithorax with passage of almost all the loops of the small intestine and transverse colon, causing a change in the course of the superior mesenteric artery and signs of intestinal distress.

Given the suspicion of cardiac tamponade and massive atelectasis secondary to diaphragmatic hernia, emergency surgery was indicated.

During the induction of anesthesia, the patient presented hemodynamic deterioration with a decrease in systolic pressure to 60 mmHg and no response to fluid therapy or vasoactive amines, which confirmed the diagnosis of obstructive shock. Midline laparotomy revealed a left hiatal diaphragmatic hernia with displacement of the entire small intestine and transverse colon through the hernia defect. The diaphragmatic hernia ring was opened in order to reduce the content, which provided immediate hemodynamic improvement. The procedure was completed with the closure of the diaphragmatic defect using non-absorbable suture, placement of condensed polytetrafluoroethylene mesh, and resection of the ischemic transverse colon.

The patient was extubated 24 h later and discharged on the sixth postoperative day after presenting a favorable evolution.

Most diaphragmatic hernias are congenital in origin.1 The appearance of a hernia after esophagectomy is a rare complication, occurring in less than 1% of patients treated with open surgery. The rate is slightly higher in laparoscopic surgery, due to the difficulty of hiatal closure using this approach and to the less frequent development of adhesions that would prevent intestinal contents from ascending to the thorax.2

Primary prevention is necessary when opening the hiatus during surgery. The defect should be repaired with non-absorbable suture and fixation of the gastroplasty to the abutments. The systematic use of mesh is controversial, and its indication should be adapted to the surgery performed while avoiding placement near an anastomosis.3

Most hiatal hernias do not cause symptoms and are diagnosed during the follow-up of another pathology.4 When symptoms do appear, they usually include vomiting, dysphagia, or weight loss.

Surgery should be considered in all cases unless the hernia is small and does not cause symptoms.5

Treatment consists of reducing hernia content, closing the defect and mesh placement. The procedure can be performed through an open or laparoscopic approach, or through the thorax in certain instances.6

An emergency like obstructive shock secondary to a diaphragmatic hernia is extremely rare and has not been previously reported as a complication after elective esophageal surgery.

In the case we have presented, the seriousness of the situation meant that our priority was to act quickly and resolve the origin of the patient’s compromised hemodynamic situation. Therefore, the first maneuver we performed was opening the diaphragmatic defect to reduce the hernia content, after which the patient regained clinical stability.

From a pathophysiological standpoint, it was the resection of part of the hiatal muscles that created a diaphragmatic defect that was not repaired and acted as a hernia orifice. This, together with the laparoscopic approach and the patient’s postoperative weight loss, were the mechanisms of action.

In conclusion, repair of the diaphragmatic defect, fixation of the gastroplasty and assessment of appropriate mesh placement during esophagectomy could have avoided the appearance of such a serious complication in a case where it was necessary to resect diaphragm muscles for oncological purposes and to open the esophageal hiatus.

Please cite this article as: García Romera Á, Montes Montero A, González García S, Morales Hernández A, Bravo Gutiérrez A. Shock obstructivo secundario a hernia diafragmática: una rara complicación tras cirugía esofágica. Cir Esp. 2020;98:488–489.