The objective of this observational, prospective, multicenter and multilevel study was to evaluate the oncological outcomes (local recurrence, metastasis and overall survival) of the Rectal Cancer Project of the Spanish Association of Surgeons (AEC) 10 years after its initiation, comparing the results with Scandinavian registries.

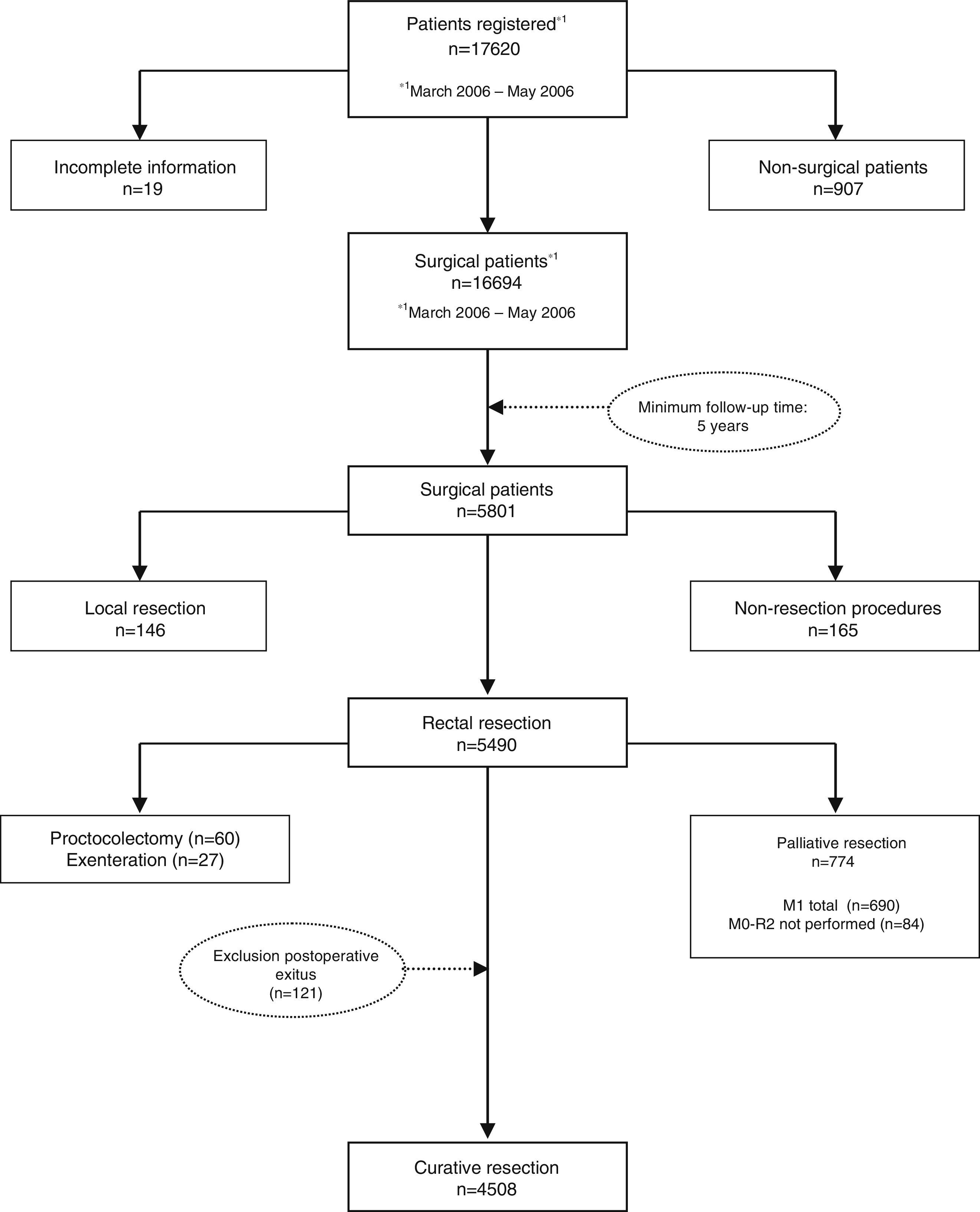

MethodsThe AEC teaching project database includes 17620 patients to date, of which 4508 were operated on with a potentially curative resection between March 2006 and December 2010. All of them come from the first 59 hospitals included in the project, and therefore followed for at least 5 years, and are the subject of the present study.

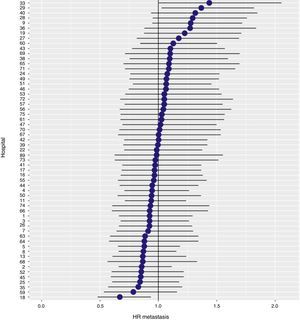

ResultsThe cumulative incidence of local recurrence was 7.3 (95% CI: 8.2–6.5), metastasis 21.0 (CI 95%: 22.4–19.7) and overall survival 72.3 (CI 95%: 80.3–77.6). The multilevel regression analysis with the hospital variable as a random effect, showed a significant variation among the hospitals for the cancer outcome variables: general survival, local recurrence and metastasis (δ2=0.053).

ConclusionsThis study indicates that the results observed in the AEC’ Rectal Cancer Project are inferior than those observed in the Scandinavian registries that we tried to emulate and that this is attributable to the variability of practice in some centers.

El objetivo de este estudio observacional, prospectivo, multicéntrico y multinivel ha sido evaluar los resultados oncológicos (recidiva local, metástasis y supervivencia global) del Proyecto del Cáncer de Recto de la Asociación Española de Cirujanos (AEC) 10 años después de su inicio, comparando los resultados con los registros escandinavos.

MétodosLa base de datos del proyecto docente de la AEC incluye hasta la fecha a 17.620 pacientes, de los cuales 4.508 fueron operados con una resección potencialmente curativa entre marzo de 2006 y diciembre de 2010. Todos ellos son provenientes de los primeros 59 hospitales incluidos en el proyecto, y por tanto seguidos al menos durante 5 años, y constituyen el objeto del presente estudio.

ResultadosLa incidencia acumulada de recidiva local fue 7,3 (IC 95%: 8,2-6,5), la de metástasis fue 21.0 (IC 95%: 22,4-19,7) y la de supervivencia global, 72,3 (IC 95%: 80,3-77,6). El análisis de regresión multinivel, con la variable hospital como un efecto aleatorio, mostró una variación significativa entre los hospitales para las variables de resultado oncológico: supervivencia general, recidiva local y metástasis (δ2=0,053).

ConclusionesEste estudio indica que los resultados observados en el Proyecto del Cáncer de Recto de la AEC son inferiores a los observados en los registros de Escandinavia a los que tratamos de emular y que ello es atribuible a la variabilidad de la práctica en algunos centros.

In order to determine the oncological results of rectal cancer treatment in Spain and whether these outcomes could be improved, the Spanish Association of Surgeons (Association Española de Cirujanos, AEC) introduced a project1 in 2006 inspired by the Norwegian Colon and Rectal Cancer Project.2 The objective of this teaching initiative was to disseminate and systematize mesorectal excision surgery initially, and later extended abdominoperineal excision,3 to the multidisciplinary groups of the 105 hospitals of the National Healthcare System that requested it and fulfilled the required conditions from 2006 to 2012 (Appendix).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the oncological results achieved by this teaching initiative 10 years after its inception and to determine whether these results have achieved the quality standards observed in the registries of the Scandinavian countries, which this project attempts to imitate.

MethodsThis multicenter observational study was carried out using the prospective database of the Rectal Cancer Project of the AEC.

Patient selection. Included for study were patients who had been treated with elective surgery at the first 59 hospitals included in the project, between March 1, 2006 and December 1, 2010, with curative resections of the rectum and with or without restoration of intestinal continuity: anterior resection (AR); abdominoperineal resection (APR) and Hartmann procedure.

We excluded non-surgical patients and those treated with non-resective operations: exploratory laparotomy or laparoscopy, stoma, and diversions. Also excluded were those who underwent the following techniques: local resection, proctocolectomy, and pelvic exenteration. Excluded as well were patients whose operations were not considered curative and patients with involvement of the distal histopathological margin and patients with urgent surgery.

Study variables. The study outcome variables were: local recurrence, metastases that appeared during follow-up, and overall survival. Confounding variables included: sex, age categorized into 3 groups (<65, 65–80, >80 years), surgical risk (measured by the ASA anesthetic risk level), tumor location classified into 3 groups from the anal margin (0–6, 7–12, 13–15cm), type of mesorectal excision (partial or total), type of operation performed (AR, APR, Hartmann procedure), intraoperative perforation of the tumor or rectum, status of the circumferential resection margin (CRM) (free or tumor invasion), use of neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment, and the pathological stage of the tumor.

Definitions and standards. According to the Clasificación Internacional de Enfermedades (CIE10-C20), rectal tumors were defined as those situated in the last 15cm measured from the anal margin using rigid rectoscope or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).4

A resection was considered potentially curative in those cases in which a locally radical procedure was performed with free distal and circumferential margins or with microscopic invasion of these margins (R0 and R1) in the absence of metastasis.

The pathologic tumor stage was classified with the fifth edition of the TNM classification (American Joint Committee on Cancer stages I–IV; fifth edition).5 Intraoperative perforation was defined as any defect of the rectal wall caused by the operation that brought the lumen of the rectum into contact with the surface. The CRM was considered invaded if neoplastic cells were found 1mm or less away.

Local recurrence was defined as the reappearance of the disease in the pelvis, including: the anastomosis and perineal wound, regardless of whether the patient had distant metastasis. Isolated recurrence in the ovaries was considered metastasis.

Given the anonymity of hospitals and patients, approval by the ethics committees of the centers included was not considered necessary, although the project had been endorsed by these committees.

Statistical AnalysisBefore conducting the analyses, an exploratory analysis of the data was used to detect extreme cases, non-response and lost cases. A univariate descriptive analysis was carried out, where the quantitative variables were summarized by means and standard deviation and the categorical variables by frequencies and percentages. The results related with the incidence of recurrence, metastasis and overall survival were presented as the total number of events and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Patients were considered at risk for experiencing the indicated events until death, loss of follow-up due to change of city of residence or end of follow-up after 5 years. The incidence of these events was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method.

Confounding variables that had a significant impact on overall survival, local recurrence and metastasis at follow-up were identified with Cox proportional hazards models. The adjustment was considered necessary to correct the confounding bias if the change between the adjusted and unadjusted effect was greater than 10%. The assumption of proportional risks was evaluated by the Therneau-Grambsch approach. The results were expressed as the hazard ratio (HR) and its 95% CI.

Since patients at the same hospital are more likely to have similar oncological outcomes (depending on patient and tumor characteristics) than those observed at other hospitals, the logistic regression was extended with the hospital variable as a random effect to correct for the non-independence of the data.

The analyses were made with the statistical packages by IBM SPSS (version 24), R (version 3.3.2) and STATA IC13, with a level of significance of 0.05.

ResultsBetween 2006 and 2012, the multidisciplinary groups (MDG) of 105 hospitals were trained in 10 courses. Of these, 23 abandoned the project and 6 hospitals have merged, leaving 3 in their place. In total, and to date, the 79 participating centers have included 17620 patients in the database.

The results presented in this study were observed in patients treated electively with curative rectal resection in the 59 participating centers between March 1, 2006 and December 31, 2010, thus having a minimum of 5 years of follow-up. In this period, once the exclusion criteria indicated in the flow chart were applied (Fig. 1), 4716 consecutive patients were treated with curative rectal resection, 4508 of which survived the operation and were included in the analysis of the oncological results.

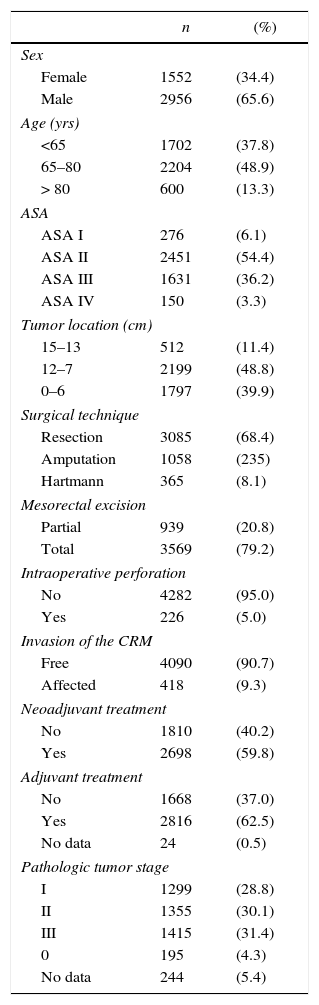

The characteristics of this cohort of patients are shown in Table 1. In 3085 (68.4%) patients AR was performed, 1058 (23.5%) were treated with APR, and 365 (8.1%) with the Hartmann procedure.

Description of the Patient Sample (n=4508).

| n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1552 | (34.4) |

| Male | 2956 | (65.6) |

| Age (yrs) | ||

| <65 | 1702 | (37.8) |

| 65–80 | 2204 | (48.9) |

| > 80 | 600 | (13.3) |

| ASA | ||

| ASA I | 276 | (6.1) |

| ASA II | 2451 | (54.4) |

| ASA III | 1631 | (36.2) |

| ASA IV | 150 | (3.3) |

| Tumor location (cm) | ||

| 15–13 | 512 | (11.4) |

| 12–7 | 2199 | (48.8) |

| 0–6 | 1797 | (39.9) |

| Surgical technique | ||

| Resection | 3085 | (68.4) |

| Amputation | 1058 | (235) |

| Hartmann | 365 | (8.1) |

| Mesorectal excision | ||

| Partial | 939 | (20.8) |

| Total | 3569 | (79.2) |

| Intraoperative perforation | ||

| No | 4282 | (95.0) |

| Yes | 226 | (5.0) |

| Invasion of the CRM | ||

| Free | 4090 | (90.7) |

| Affected | 418 | (9.3) |

| Neoadjuvant treatment | ||

| No | 1810 | (40.2) |

| Yes | 2698 | (59.8) |

| Adjuvant treatment | ||

| No | 1668 | (37.0) |

| Yes | 2816 | (62.5) |

| No data | 24 | (0.5) |

| Pathologic tumor stage | ||

| I | 1299 | (28.8) |

| II | 1355 | (30.1) |

| III | 1415 | (31.4) |

| 0 | 195 | (4.3) |

| No data | 244 | (5.4) |

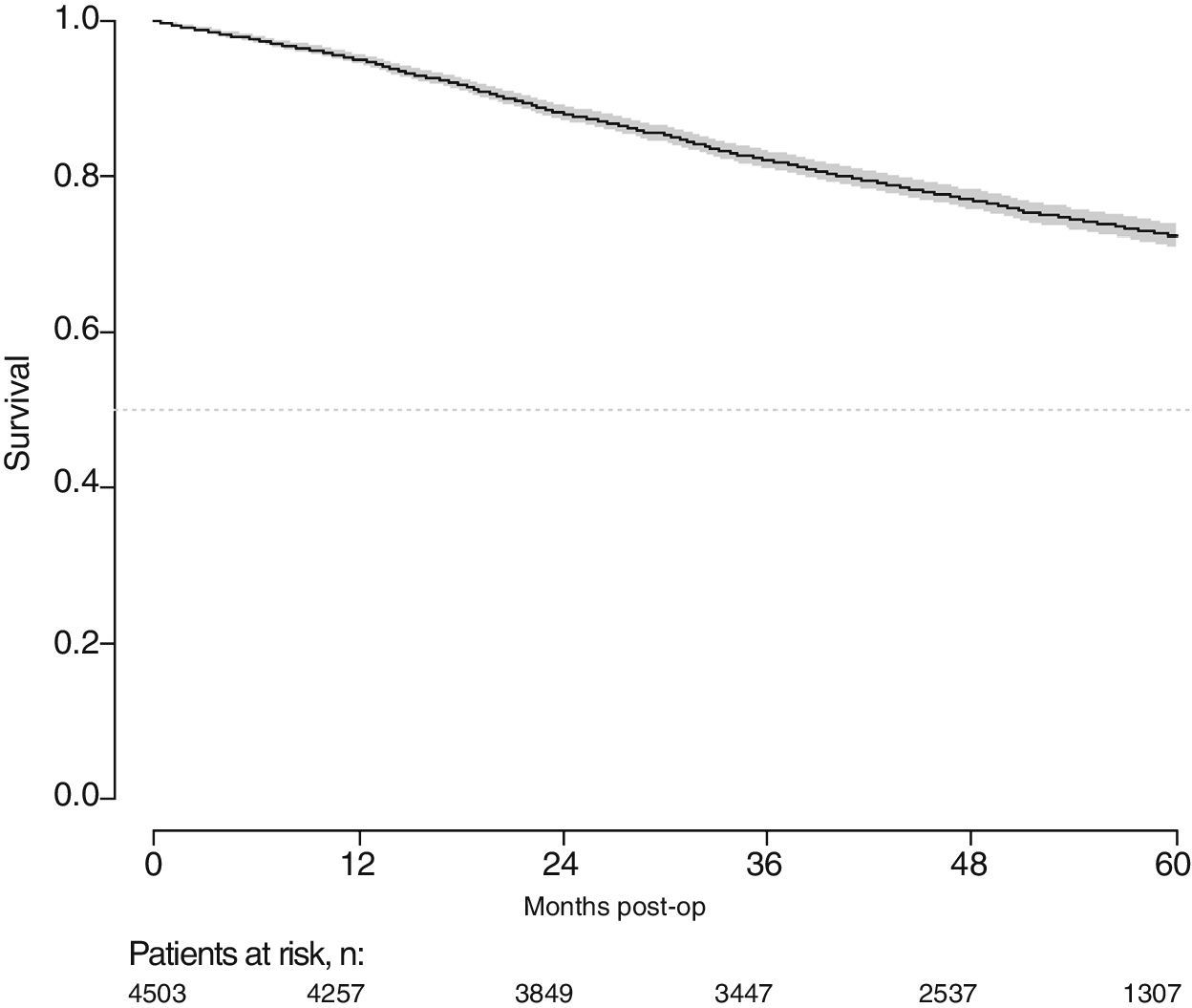

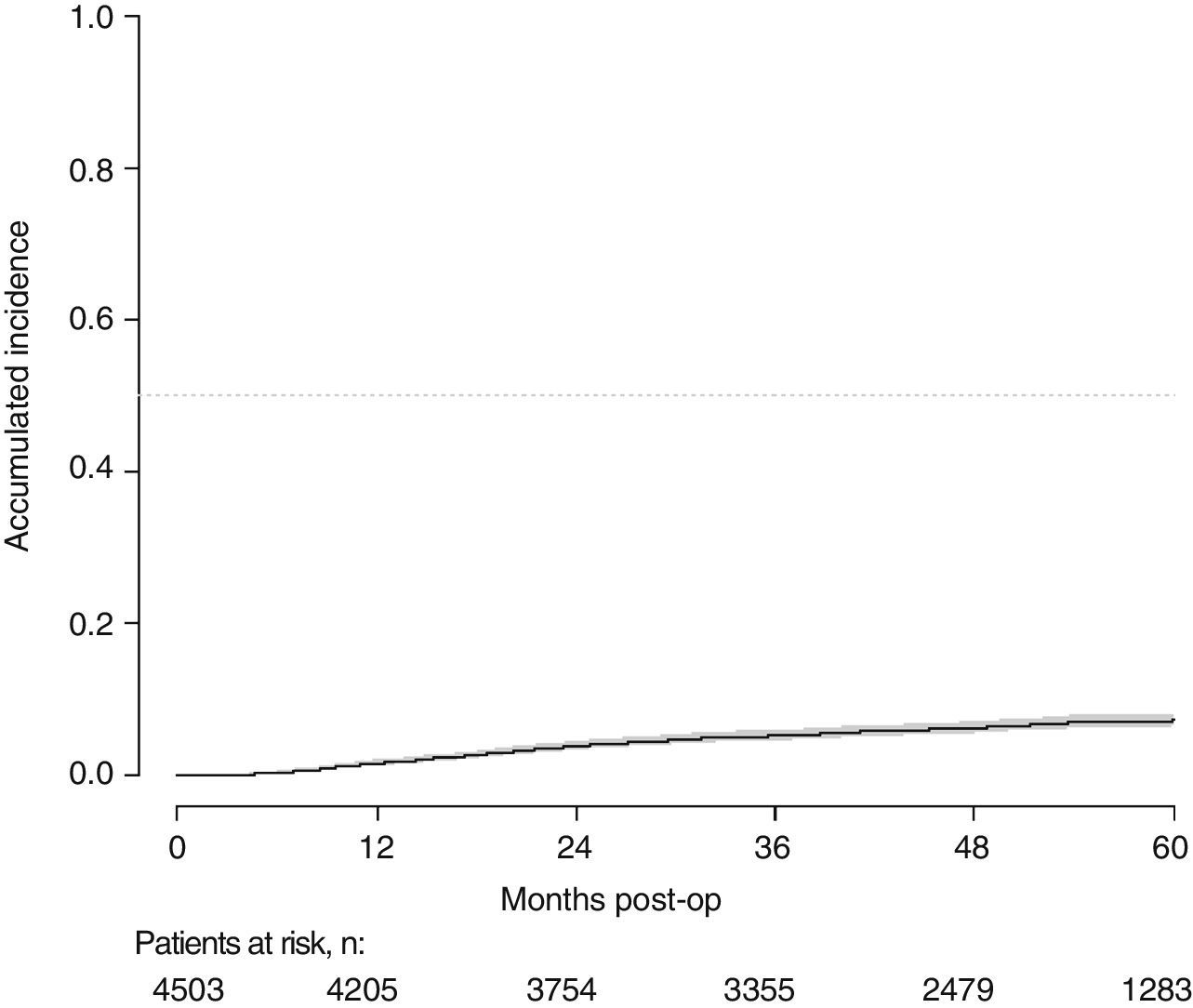

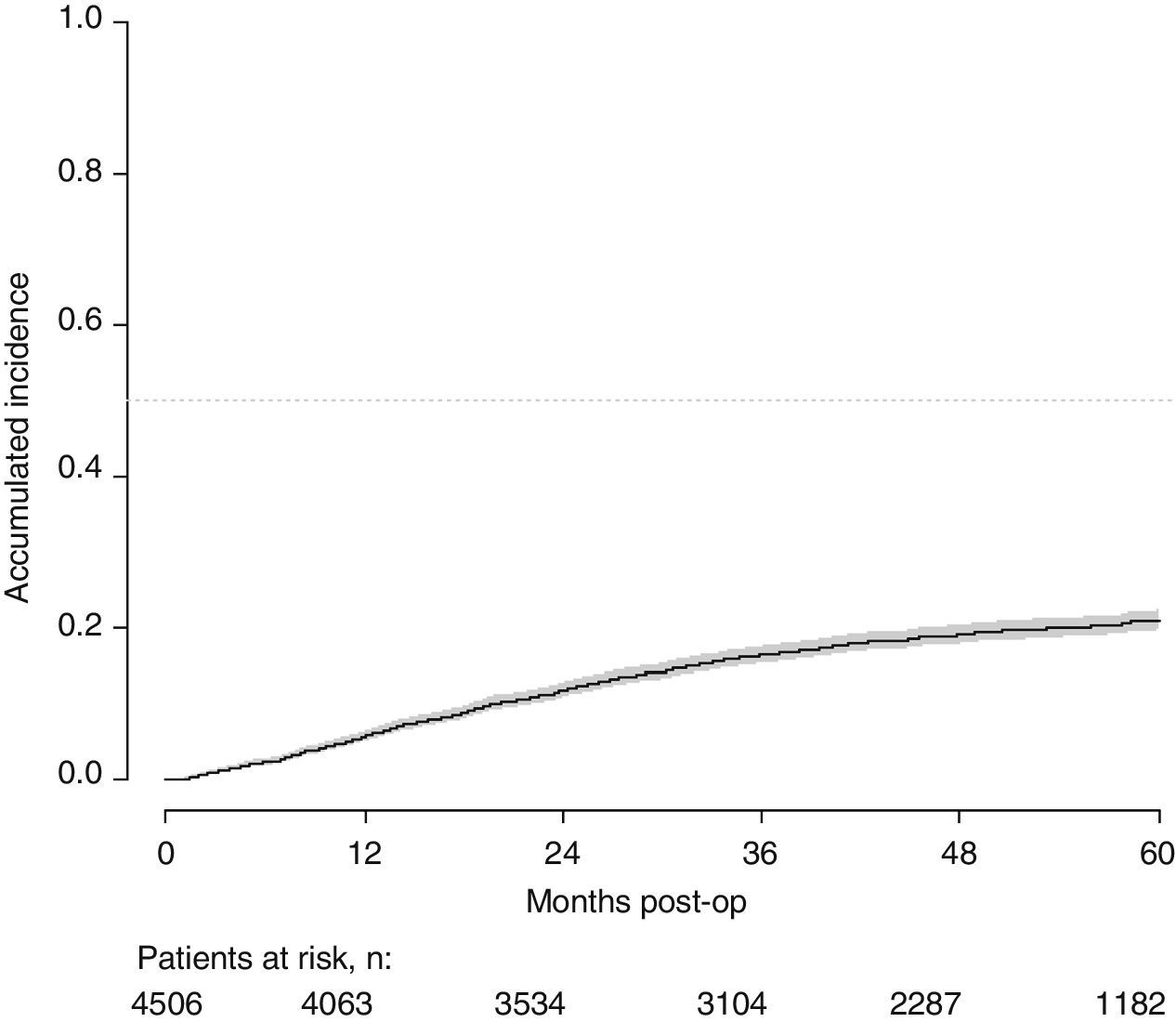

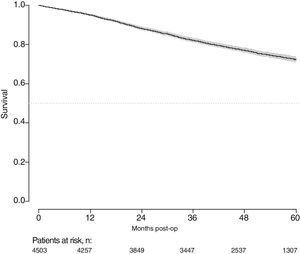

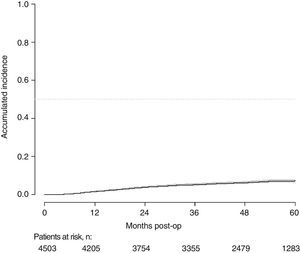

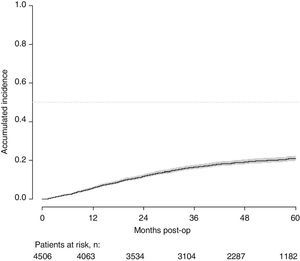

With a follow-up of at least 5 years, the cumulative incidence of local recurrence was 7.3% (95% CI: 6.5–8.2) (Fig. 2), the rate of metastasis at follow-up was 21% (95% CI: 19.7–22.4) (Fig. 3) and overall survival was 72.3% (95% CI: 70.9–73.8) (Fig. 4).

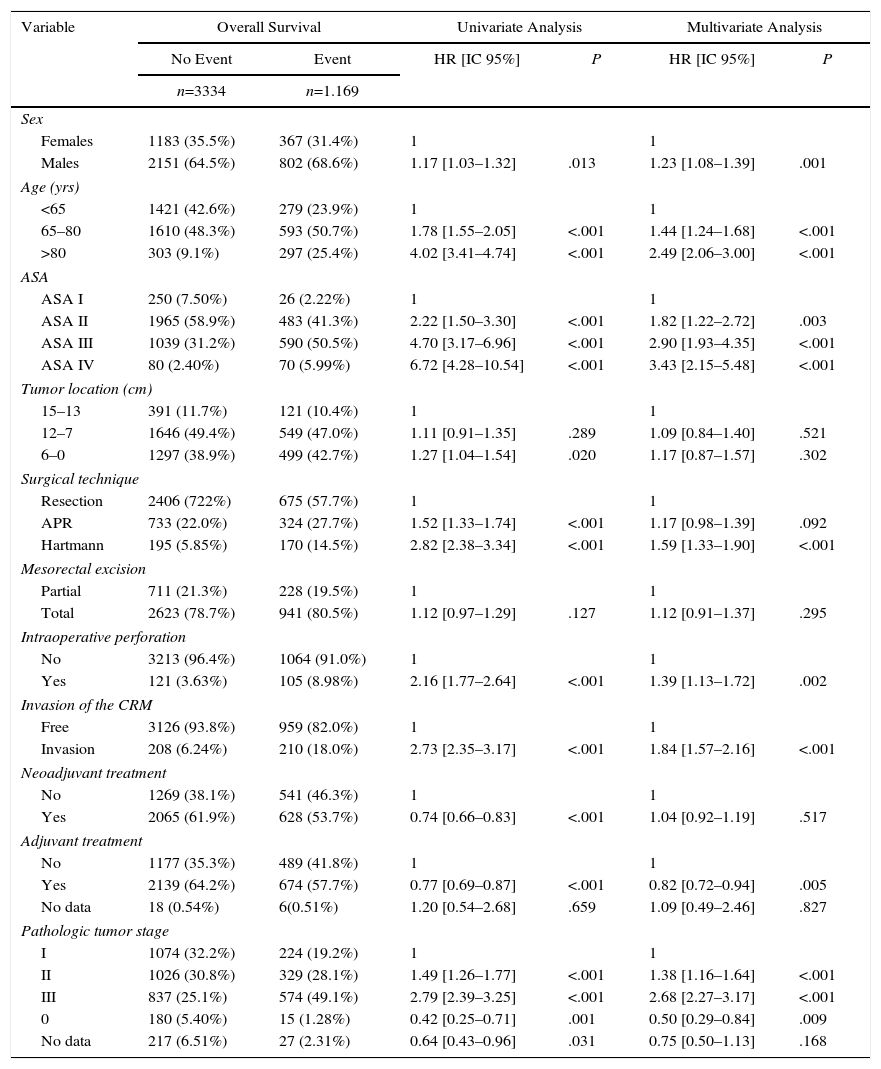

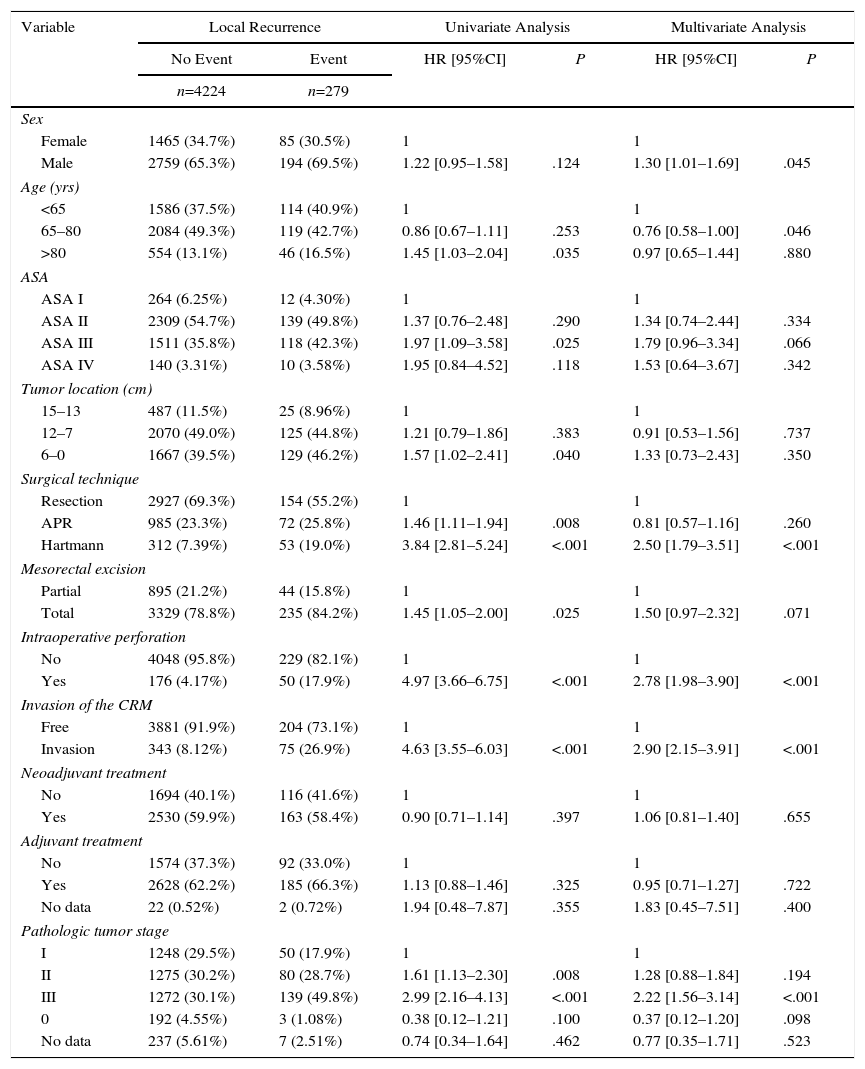

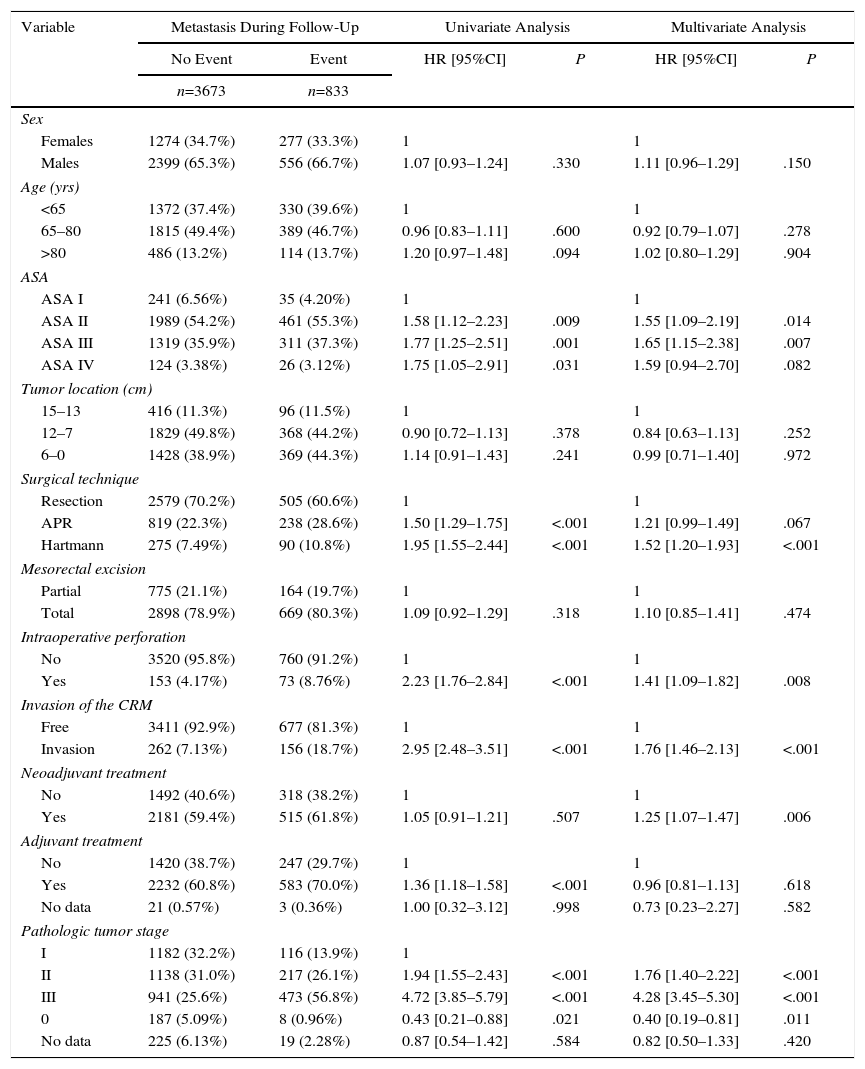

The results of the univariate and multivariate analyses performed to determine the influence of confounding variables on the oncological results are shown in Tables 2–4. Intraoperative perforation, CRM invasion, advanced tumor stages and the Hartmann procedure negatively influenced the 3 outcome variables: local recurrence, metastasis in follow-up and overall survival. Male sex also negatively influenced local recurrence and overall survival. In addition, advanced patient age and higher ASA risk negatively influenced overall survival.

Influence of the Confounding Variables on Overall Survival.

| Variable | Overall Survival | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Event | Event | HR [IC 95%] | P | HR [IC 95%] | P | |

| n=3334 | n=1.169 | |||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Females | 1183 (35.5%) | 367 (31.4%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Males | 2151 (64.5%) | 802 (68.6%) | 1.17 [1.03–1.32] | .013 | 1.23 [1.08–1.39] | .001 |

| Age (yrs) | ||||||

| <65 | 1421 (42.6%) | 279 (23.9%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 65–80 | 1610 (48.3%) | 593 (50.7%) | 1.78 [1.55–2.05] | <.001 | 1.44 [1.24–1.68] | <.001 |

| >80 | 303 (9.1%) | 297 (25.4%) | 4.02 [3.41–4.74] | <.001 | 2.49 [2.06–3.00] | <.001 |

| ASA | ||||||

| ASA I | 250 (7.50%) | 26 (2.22%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| ASA II | 1965 (58.9%) | 483 (41.3%) | 2.22 [1.50–3.30] | <.001 | 1.82 [1.22–2.72] | .003 |

| ASA III | 1039 (31.2%) | 590 (50.5%) | 4.70 [3.17–6.96] | <.001 | 2.90 [1.93–4.35] | <.001 |

| ASA IV | 80 (2.40%) | 70 (5.99%) | 6.72 [4.28–10.54] | <.001 | 3.43 [2.15–5.48] | <.001 |

| Tumor location (cm) | ||||||

| 15–13 | 391 (11.7%) | 121 (10.4%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 12–7 | 1646 (49.4%) | 549 (47.0%) | 1.11 [0.91–1.35] | .289 | 1.09 [0.84–1.40] | .521 |

| 6–0 | 1297 (38.9%) | 499 (42.7%) | 1.27 [1.04–1.54] | .020 | 1.17 [0.87–1.57] | .302 |

| Surgical technique | ||||||

| Resection | 2406 (722%) | 675 (57.7%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| APR | 733 (22.0%) | 324 (27.7%) | 1.52 [1.33–1.74] | <.001 | 1.17 [0.98–1.39] | .092 |

| Hartmann | 195 (5.85%) | 170 (14.5%) | 2.82 [2.38–3.34] | <.001 | 1.59 [1.33–1.90] | <.001 |

| Mesorectal excision | ||||||

| Partial | 711 (21.3%) | 228 (19.5%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Total | 2623 (78.7%) | 941 (80.5%) | 1.12 [0.97–1.29] | .127 | 1.12 [0.91–1.37] | .295 |

| Intraoperative perforation | ||||||

| No | 3213 (96.4%) | 1064 (91.0%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 121 (3.63%) | 105 (8.98%) | 2.16 [1.77–2.64] | <.001 | 1.39 [1.13–1.72] | .002 |

| Invasion of the CRM | ||||||

| Free | 3126 (93.8%) | 959 (82.0%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Invasion | 208 (6.24%) | 210 (18.0%) | 2.73 [2.35–3.17] | <.001 | 1.84 [1.57–2.16] | <.001 |

| Neoadjuvant treatment | ||||||

| No | 1269 (38.1%) | 541 (46.3%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 2065 (61.9%) | 628 (53.7%) | 0.74 [0.66–0.83] | <.001 | 1.04 [0.92–1.19] | .517 |

| Adjuvant treatment | ||||||

| No | 1177 (35.3%) | 489 (41.8%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 2139 (64.2%) | 674 (57.7%) | 0.77 [0.69–0.87] | <.001 | 0.82 [0.72–0.94] | .005 |

| No data | 18 (0.54%) | 6(0.51%) | 1.20 [0.54–2.68] | .659 | 1.09 [0.49–2.46] | .827 |

| Pathologic tumor stage | ||||||

| I | 1074 (32.2%) | 224 (19.2%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| II | 1026 (30.8%) | 329 (28.1%) | 1.49 [1.26–1.77] | <.001 | 1.38 [1.16–1.64] | <.001 |

| III | 837 (25.1%) | 574 (49.1%) | 2.79 [2.39–3.25] | <.001 | 2.68 [2.27–3.17] | <.001 |

| 0 | 180 (5.40%) | 15 (1.28%) | 0.42 [0.25–0.71] | .001 | 0.50 [0.29–0.84] | .009 |

| No data | 217 (6.51%) | 27 (2.31%) | 0.64 [0.43–0.96] | .031 | 0.75 [0.50–1.13] | .168 |

Influence of the Confounding Variables on Local Recurrence.

| Variable | Local Recurrence | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Event | Event | HR [95%CI] | P | HR [95%CI] | P | |

| n=4224 | n=279 | |||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 1465 (34.7%) | 85 (30.5%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Male | 2759 (65.3%) | 194 (69.5%) | 1.22 [0.95–1.58] | .124 | 1.30 [1.01–1.69] | .045 |

| Age (yrs) | ||||||

| <65 | 1586 (37.5%) | 114 (40.9%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 65–80 | 2084 (49.3%) | 119 (42.7%) | 0.86 [0.67–1.11] | .253 | 0.76 [0.58–1.00] | .046 |

| >80 | 554 (13.1%) | 46 (16.5%) | 1.45 [1.03–2.04] | .035 | 0.97 [0.65–1.44] | .880 |

| ASA | ||||||

| ASA I | 264 (6.25%) | 12 (4.30%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| ASA II | 2309 (54.7%) | 139 (49.8%) | 1.37 [0.76–2.48] | .290 | 1.34 [0.74–2.44] | .334 |

| ASA III | 1511 (35.8%) | 118 (42.3%) | 1.97 [1.09–3.58] | .025 | 1.79 [0.96–3.34] | .066 |

| ASA IV | 140 (3.31%) | 10 (3.58%) | 1.95 [0.84–4.52] | .118 | 1.53 [0.64–3.67] | .342 |

| Tumor location (cm) | ||||||

| 15–13 | 487 (11.5%) | 25 (8.96%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 12–7 | 2070 (49.0%) | 125 (44.8%) | 1.21 [0.79–1.86] | .383 | 0.91 [0.53–1.56] | .737 |

| 6–0 | 1667 (39.5%) | 129 (46.2%) | 1.57 [1.02–2.41] | .040 | 1.33 [0.73–2.43] | .350 |

| Surgical technique | ||||||

| Resection | 2927 (69.3%) | 154 (55.2%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| APR | 985 (23.3%) | 72 (25.8%) | 1.46 [1.11–1.94] | .008 | 0.81 [0.57–1.16] | .260 |

| Hartmann | 312 (7.39%) | 53 (19.0%) | 3.84 [2.81–5.24] | <.001 | 2.50 [1.79–3.51] | <.001 |

| Mesorectal excision | ||||||

| Partial | 895 (21.2%) | 44 (15.8%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Total | 3329 (78.8%) | 235 (84.2%) | 1.45 [1.05–2.00] | .025 | 1.50 [0.97–2.32] | .071 |

| Intraoperative perforation | ||||||

| No | 4048 (95.8%) | 229 (82.1%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 176 (4.17%) | 50 (17.9%) | 4.97 [3.66–6.75] | <.001 | 2.78 [1.98–3.90] | <.001 |

| Invasion of the CRM | ||||||

| Free | 3881 (91.9%) | 204 (73.1%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Invasion | 343 (8.12%) | 75 (26.9%) | 4.63 [3.55–6.03] | <.001 | 2.90 [2.15–3.91] | <.001 |

| Neoadjuvant treatment | ||||||

| No | 1694 (40.1%) | 116 (41.6%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 2530 (59.9%) | 163 (58.4%) | 0.90 [0.71–1.14] | .397 | 1.06 [0.81–1.40] | .655 |

| Adjuvant treatment | ||||||

| No | 1574 (37.3%) | 92 (33.0%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 2628 (62.2%) | 185 (66.3%) | 1.13 [0.88–1.46] | .325 | 0.95 [0.71–1.27] | .722 |

| No data | 22 (0.52%) | 2 (0.72%) | 1.94 [0.48–7.87] | .355 | 1.83 [0.45–7.51] | .400 |

| Pathologic tumor stage | ||||||

| I | 1248 (29.5%) | 50 (17.9%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| II | 1275 (30.2%) | 80 (28.7%) | 1.61 [1.13–2.30] | .008 | 1.28 [0.88–1.84] | .194 |

| III | 1272 (30.1%) | 139 (49.8%) | 2.99 [2.16–4.13] | <.001 | 2.22 [1.56–3.14] | <.001 |

| 0 | 192 (4.55%) | 3 (1.08%) | 0.38 [0.12–1.21] | .100 | 0.37 [0.12–1.20] | .098 |

| No data | 237 (5.61%) | 7 (2.51%) | 0.74 [0.34–1.64] | .462 | 0.77 [0.35–1.71] | .523 |

Influence of the Confounding Variables on Metastasis.

| Variable | Metastasis During Follow-Up | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Event | Event | HR [95%CI] | P | HR [95%CI] | P | |

| n=3673 | n=833 | |||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Females | 1274 (34.7%) | 277 (33.3%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Males | 2399 (65.3%) | 556 (66.7%) | 1.07 [0.93–1.24] | .330 | 1.11 [0.96–1.29] | .150 |

| Age (yrs) | ||||||

| <65 | 1372 (37.4%) | 330 (39.6%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 65–80 | 1815 (49.4%) | 389 (46.7%) | 0.96 [0.83–1.11] | .600 | 0.92 [0.79–1.07] | .278 |

| >80 | 486 (13.2%) | 114 (13.7%) | 1.20 [0.97–1.48] | .094 | 1.02 [0.80–1.29] | .904 |

| ASA | ||||||

| ASA I | 241 (6.56%) | 35 (4.20%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| ASA II | 1989 (54.2%) | 461 (55.3%) | 1.58 [1.12–2.23] | .009 | 1.55 [1.09–2.19] | .014 |

| ASA III | 1319 (35.9%) | 311 (37.3%) | 1.77 [1.25–2.51] | .001 | 1.65 [1.15–2.38] | .007 |

| ASA IV | 124 (3.38%) | 26 (3.12%) | 1.75 [1.05–2.91] | .031 | 1.59 [0.94–2.70] | .082 |

| Tumor location (cm) | ||||||

| 15–13 | 416 (11.3%) | 96 (11.5%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 12–7 | 1829 (49.8%) | 368 (44.2%) | 0.90 [0.72–1.13] | .378 | 0.84 [0.63–1.13] | .252 |

| 6–0 | 1428 (38.9%) | 369 (44.3%) | 1.14 [0.91–1.43] | .241 | 0.99 [0.71–1.40] | .972 |

| Surgical technique | ||||||

| Resection | 2579 (70.2%) | 505 (60.6%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| APR | 819 (22.3%) | 238 (28.6%) | 1.50 [1.29–1.75] | <.001 | 1.21 [0.99–1.49] | .067 |

| Hartmann | 275 (7.49%) | 90 (10.8%) | 1.95 [1.55–2.44] | <.001 | 1.52 [1.20–1.93] | <.001 |

| Mesorectal excision | ||||||

| Partial | 775 (21.1%) | 164 (19.7%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Total | 2898 (78.9%) | 669 (80.3%) | 1.09 [0.92–1.29] | .318 | 1.10 [0.85–1.41] | .474 |

| Intraoperative perforation | ||||||

| No | 3520 (95.8%) | 760 (91.2%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 153 (4.17%) | 73 (8.76%) | 2.23 [1.76–2.84] | <.001 | 1.41 [1.09–1.82] | .008 |

| Invasion of the CRM | ||||||

| Free | 3411 (92.9%) | 677 (81.3%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Invasion | 262 (7.13%) | 156 (18.7%) | 2.95 [2.48–3.51] | <.001 | 1.76 [1.46–2.13] | <.001 |

| Neoadjuvant treatment | ||||||

| No | 1492 (40.6%) | 318 (38.2%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 2181 (59.4%) | 515 (61.8%) | 1.05 [0.91–1.21] | .507 | 1.25 [1.07–1.47] | .006 |

| Adjuvant treatment | ||||||

| No | 1420 (38.7%) | 247 (29.7%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 2232 (60.8%) | 583 (70.0%) | 1.36 [1.18–1.58] | <.001 | 0.96 [0.81–1.13] | .618 |

| No data | 21 (0.57%) | 3 (0.36%) | 1.00 [0.32–3.12] | .998 | 0.73 [0.23–2.27] | .582 |

| Pathologic tumor stage | ||||||

| I | 1182 (32.2%) | 116 (13.9%) | 1 | |||

| II | 1138 (31.0%) | 217 (26.1%) | 1.94 [1.55–2.43] | <.001 | 1.76 [1.40–2.22] | <.001 |

| III | 941 (25.6%) | 473 (56.8%) | 4.72 [3.85–5.79] | <.001 | 4.28 [3.45–5.30] | <.001 |

| 0 | 187 (5.09%) | 8 (0.96%) | 0.43 [0.21–0.88] | .021 | 0.40 [0.19–0.81] | .011 |

| No data | 225 (6.13%) | 19 (2.28%) | 0.87 [0.54–1.42] | .584 | 0.82 [0.50–1.33] | .420 |

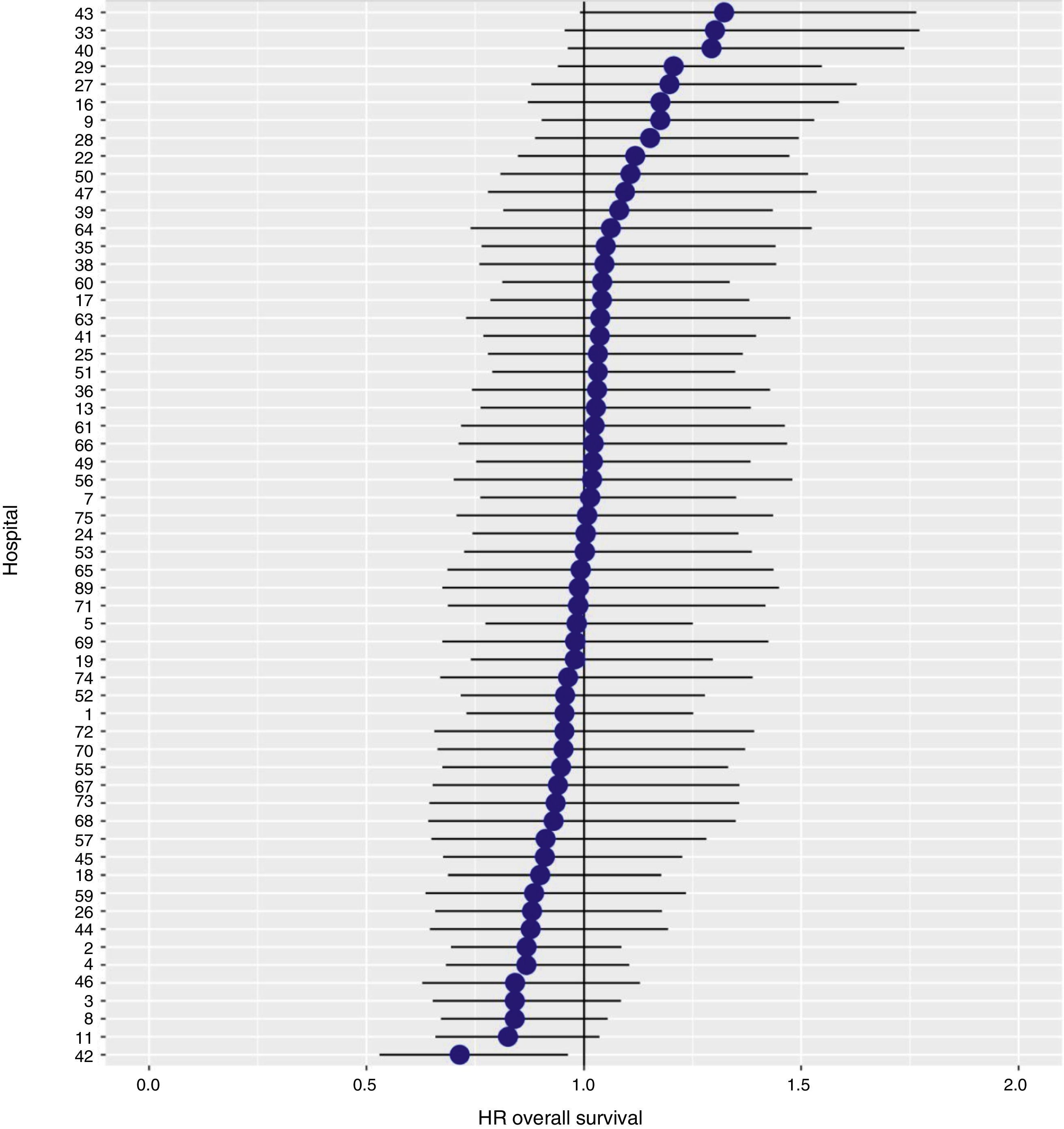

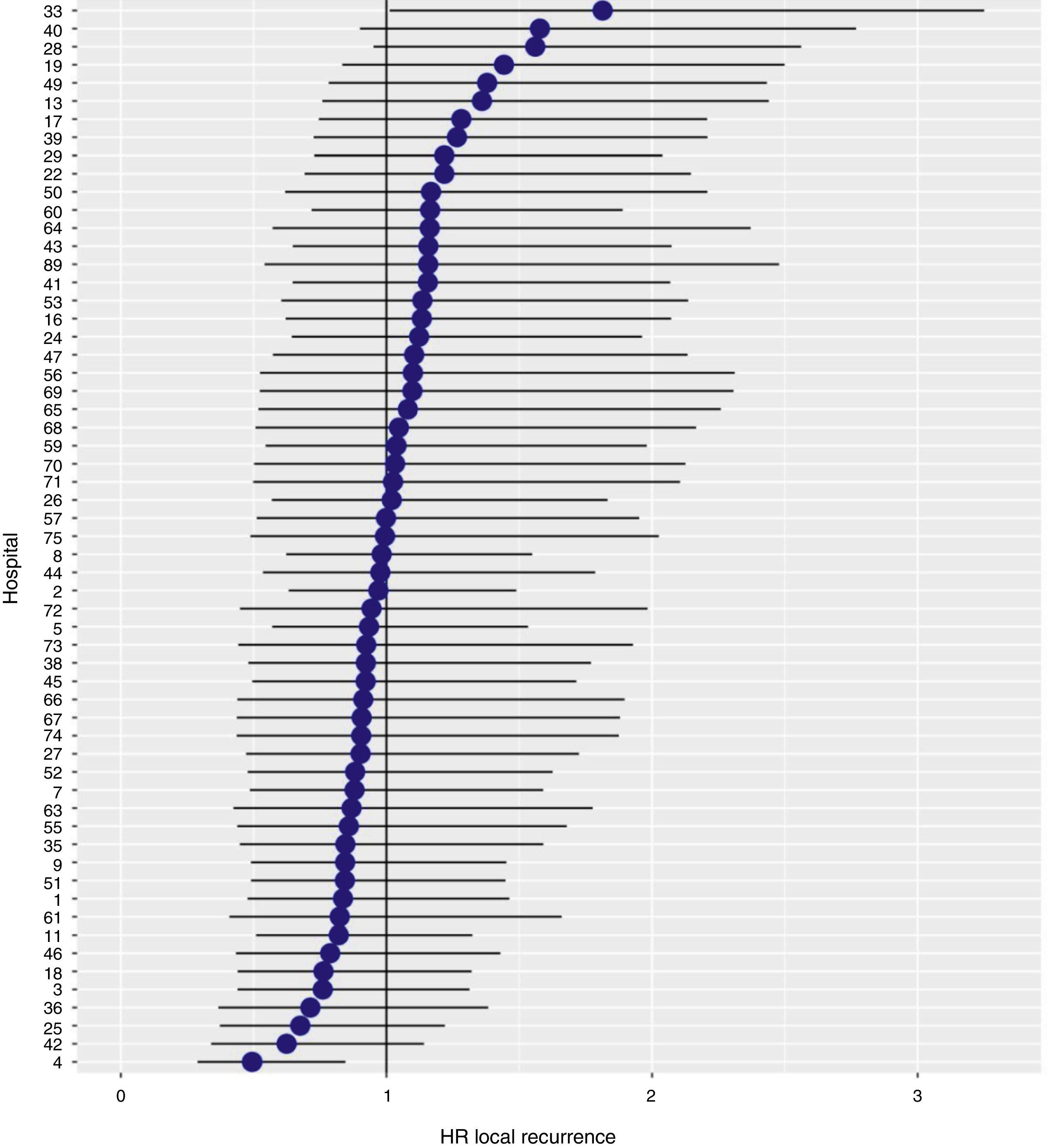

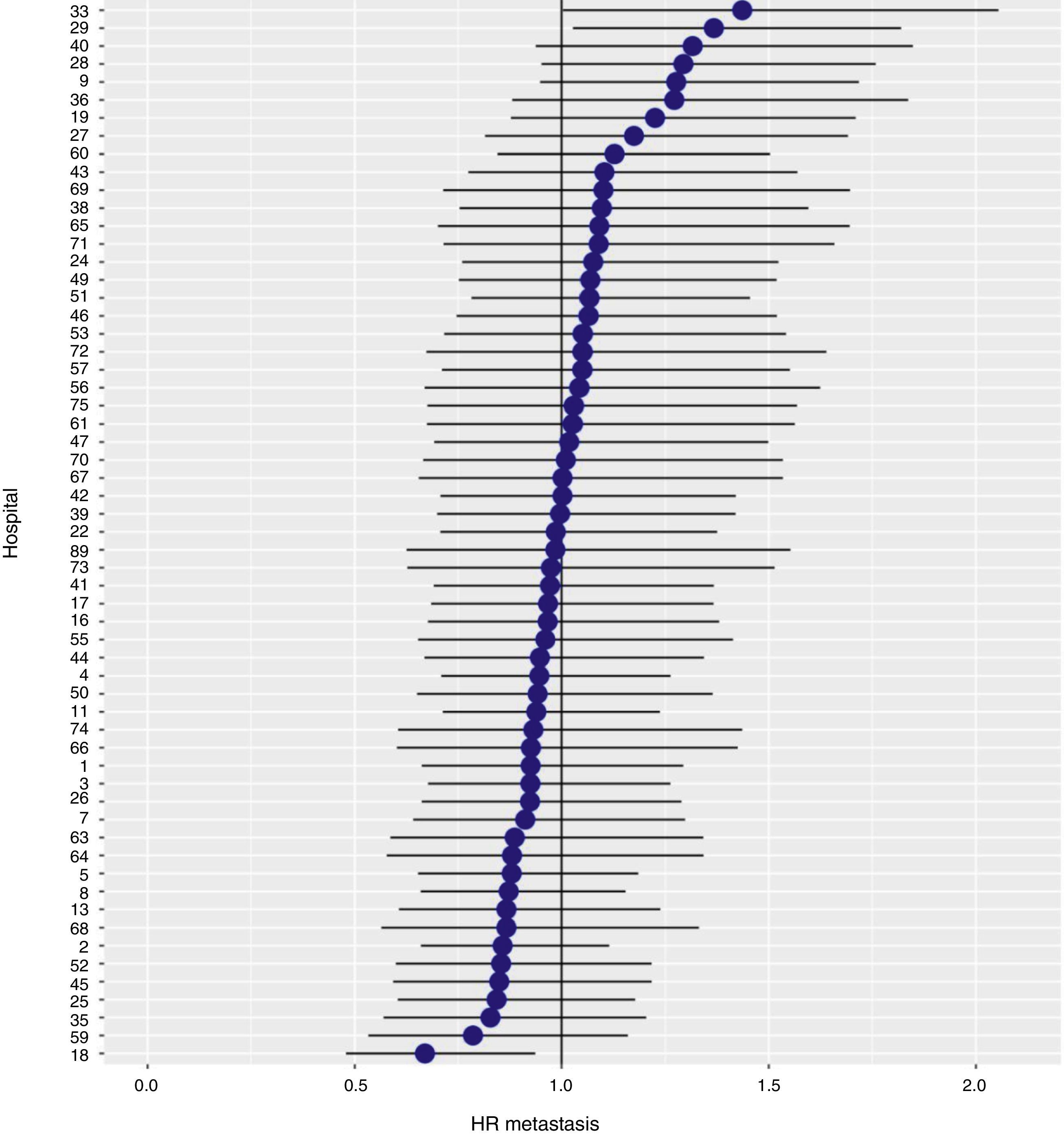

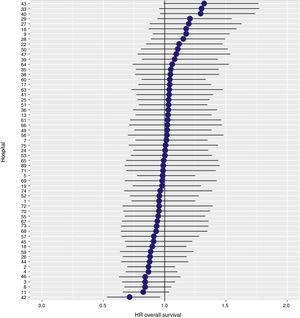

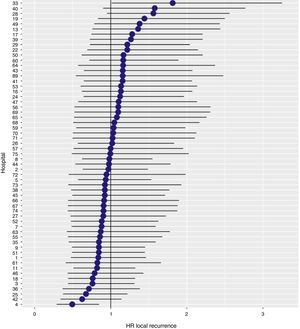

The results of the logistic regression model, with the hospital variable as a random effect, showed a significant variation among the hospitals for all the result variables (Figs. 5–7).

This study shows a local recurrence rate of 7.3% (95% CI: 6.5–8.2), metastasis during follow-up of 21% (95% CI: 19.7–22.4) and overall survival of 72.3% (95% CI: 70.9–73.8) observed in the Rectal Cancer Project in a cohort of 4508 consecutive patients followed for 5 years.

The greatest weakness of this study has to do with the voluntary nature of inclusion of the data in the AEC Rectal Cancer Project, especially when compared to the registries of the Scandinavian countries,6–8 in which the inclusion of data in the registry is mandatory. However, as already indicated in more detail,9 various initiatives have been taken to avoid voluntary or involuntary inclusion and information biases. Unfortunately, due to the anonymous nature of the data and the lack of other sources to verify the information in our country, the data from this study indicate the recorded rates of local recurrence, metastasis and overall survival.

The risk factors for tumor recurrence, and therefore worse oncological results, coincide with previous descriptions10 (tumor perforation, CRM invasion, advanced tumor stages and Hartmann procedure) with no significant associations.

The results observed in the AEC Rectal Cancer Project are lower than those observed in the Scandinavian registries that we attempt to emulate. The local recurrence rate (7.3%) is higher than that observed in Norway (5.0%)6 and Sweden (4.0%)7; this result indicator is not evaluated in the Danish registry.8 The overall survival rate in this project (72.3%) is between the rates published by the Norwegian and Swedish registries (81%)7 and the Danish registry (68%).8

In addition, the rate of local recurrence observed in this study, in which the results of 59 hospitals have been used, has been slightly higher than the rate observed in a previous analysis of the data provided by the first 36 hospitals integrated in the study (6.6%).10 However, this negative variation of the results has also been observed in the Norwegian and Swedish registries, in which the local recurrence figures have increased from 3 to 5 and 4%, respectively.7 So, perhaps the explanation of this fact could be attributed to the loss of attention of the multidisciplinary teams of some hospitals and to interhospital differences.

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate that the results observed in the AEC Rectal Cancer Project are inferior to those observed in the Scandinavian registries that we try to emulate, and that this is attributable to the variability of the practice at some hospitals.

AuthorshipAll the authors have participated in the study design, article composition, critical review and approval of the final version. María Buxó was responsible for the data collection, data analysis and statistical analysis.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Hector Ortiz for his coordination of the Vikingo Project and this pAPR.

Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca (J.A. Lujan Mompean)

Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge (S. Biondo, D. Fracalvieri)

Hospital Virgen del Camino-Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra (M. de Miguel Velasco, M.A. Ciga Lozano)

Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia (A. Espí Macias)

Hospital Universitari de Girona Dr. Josep Trueta (A. Codina Cazador, F. Olivet Pujol)

Hospital de Sagunto (M.D. Ruiz Carmona)

Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron de Barcelona (E. Espin Basany, Fancesc Vallribera)

Hospital Universitario La Fe de Valencia (E. Garcia-Granero, R. Palasí Gimenez)

Complejo Hospitalario de Ourense (A. Parajo Calvo)

Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol de Badalona (I. Camps Ausas, M. Piñol Pascual)

Hospital Lluis Alcanyis de Xàtiva (V. Viciano Pascual)

Complejo Asistencial de Burgos (E. Alonso Alonso)

Hospital del Mar de Barcelona (M. Pera Roman)

Complejo Asistencial de Salamanca (J. Garcia Garcia)

Hospital Gregorio Marañón de Madrid (M. Rodriguez Martin)

Hospital Torrecárdenas de Almería (A. Reina Duarte)

Hospital General Universitario de Valencia (M.J. Garcia Coret, M. Garcia Botella)

Hospital Txagorritxu de Vitoria (J. Errasti Alustiza)

Hospital Donostia (J.A. Múgica Martinera)

Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía de Córdoba (J. Gomez Barbadillo)

Hospital General Juan Ramón Jimenez de Huelva (M. Orelogio Orozco, R. Rada Morgades)

Hospital Arnau de Vilanova de Valencia (N. Uribe Quintana)

Hospital General de Jerez (J. de Dios Franco Osorio)

Hospital General Universitario de Elche (A. Arroyo Sebastian)

Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova de Lleida (J.E. Sierra Grañon)

Hospital Universitari de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau de Barcelona (P. Hernandez Casanovas, M. Martinez, J. Bollo)

Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela (J. Paredes Cotore)

Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén (G. Martinez Gallego, J. Gutierrez)

Hospital Clínico San Carlos de Madrid (M. Garcia Alonso)

Hospital de Cabueñes de Gijón (G. Carreño Villarreal)

Hospital General de Albacete (J. Cifuentes Tebar)

Hospital Miguel Servet de Zaragoza (J. Monzón Abad)

Hospital Xeral de Lugo (O. Maseda Díaz)

Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada (D. Huerga Alvarez)

Hospital Clínico y Provincial de Barcelona (L. Flores)

Hospital Universitari Joan XXIII de Tarragona (M. Millan Schediling)

Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves (I. Segura Jimenez, P. Palma Carazo)

Hospital Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria de Tenerife (J.G. Díaz Mejías)

Complejo Hospitalario de Badajoz (J. Salas Martínez)

Hospital Clínico Universitario San Cecilio de Granada (F. Pérez Benítez)

Hospital de Requena (J.C. Bernal Sprekelsen)

Hospital General Universitario de Alicante (F. Lluis Casajuana)

Hospital Virgen Macarena de Sevilla (L. Capitán Morales, J. Valdés Hernández)

Complejo Hospitalario de Vigo (Xeral + Meixoeiro) (E. Casal Nuñez, N. Cáceres Alvarado)

Hospital Infanta Sofía de Madrid (J. Martinez Alegre, R. Cantero Cid)

Hospital Policlínico Povisa de Vigo (A.M. Estevez Diz)

Hospital Virgen del Rocío de Sevilla (M. Victoria Maestre, J.M. Díaz Pavón)

Hospital San Juan de Dios del Aljarafe de Sevilla (M. Reig Pérez, A. Amaya Cortijo)

Hospital Nuestra Señora de Sonsoles de Ávila (J.A. Carmona Saez)

Hospital Universitario de Getafe (F.J. Jimenez Miramón)

Hospital General de Granollers (D. Ribé Serrat)

Hospital Universitario La Paz de Madrid (I. Prieto Nieto)

Hospital Dr. Peset de Valencia (T. Torres Sanchez, E. Martí Martínez)

Hospital General Rafael Mendez de Murcia (S. Rodrigo del Valle, G.S anchez de la Villa)

Hospital General Reina Sofía de Murcia (P. Barra Baños)

Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara de Cáceres (F. Romero Aceituno)

Hospital Torrevieja Salud (UTE) (A. Garcea)

Hospital de Santa María de Lleida (R. Batlle Solé)

Hospital Virgen del Puerto de Plasencia (J.A. Pérez García)

Hospital de Segovia (G. Ais Conde)

Hospital de Reus (S. Blanco)

Instituto Valenciano de Oncología (IVO) (A. García Fadrique, R. Estevan Estevan)

Hospital de Viladecans (A. Sueiras Gil)

Hospital de Cruces (J.M. García García, A. Lamiquiz Vallejo)

Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal de Madrid (J. Die Trill)

Hospital de Manises (A. Solana Bueno)

Hospital La Ribera, Alzira (F.J. Blanco Gonzalez)

Hospital Nuestra Señora del Rosell (A. Lage Laredo)

Hospital de Mérida (J.L. Dominguez Tristancho)

Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón (P. Dujovne Lindenbaum)

Hospital de Henares, Coslada (N. Palencia García)

Hospital de Vinaroz (R. Adell Carceller)

Onkologika de San Sebastian (R. Martinez Pardavila)

Consorci Sanitari Integral (Hospital General de L’Hospitalet y Hospital Moisés Broggi) (L. Ortiz de Zarate)

Complejo Hospitalario de Palencia (A.M. Huidobro Piriz)

Fundación Jimenez Díaz (C. Pastor Idoate)

Hospital de Torrejón (J.A. Garijo Alvarez)

Hospital Puerto Real de Cádiz (M. de la Vega Olías)

Hospital Espíritu Santo de Santa Coloma de Gramanet (M. López Lara)

In Appendix you can consult the list of the participating centers in the Project of the Ca’ncer de Recto of the Spanish Association of Surgeons.

Please cite this article as: Codina Cazador A, Biondo S, Basany EE, Enriquez-Navascues JM, Garcia-Granero E, Roig Vila JV, et al. Resultados oncológicos del Proyecto docente del Cáncer de Recto en España 10 años después de su inicio. Cir Esp. 2017;95:577–587.